Project Canterbury

Rev. Anthony Verren, Pastor of the

French Episcopal Church of the Saint-Esprit, at New-York, Judged

by His Works.

By Peter Barthelemy.

New York: Sold by the Booksellers, 1840.

A WORD FROM THE AUTHOR.

Relata refero.

Chance has placed in our hands, incontestable proofs of a

habit of slandering of so alarming a nature to society, that

for a long while we hesitated to believe even the testimony of

our own eyes and ears: the mind rebelled against such conviction.

We finally, however, determined to investigate the nature

of the evidence submitted to us, and the result of this enquiry

has but added to the mass of proof of which we were already possessed.

But here a difficulty arose: the offender is a Priest, not

a poor, unknown, meek, self-denying follower of Christ; not a

misanthropic, hypocritical Heraclitus; but one who is rich, honored,

blessed with health, [1/2] gay, merry, fond of wordly pleasure,

and sporting with all

At court and in the city.

What were we to do? to deliver him up to the ordinary mode

of judical proceedings? to provoke disputes in which would be

exposed a course of iniquity, alike painful to the witnesses

and his victims; disagreeable to the judge and the jury, and

dangerous to be published in their awful simplicity? And for

what purpose? to obtain a miserable pecuniary compensation, and

leave in the annals of New York the imperishable monument of

a scandal so affecting to morals and religion!

Having maturely considered these things we have abandoned

all idea of a criminal prosecution commenced by us, being fully

prepared, however, to defend ourselves if attacked, remaining

faithful to the principle,

If you wish for peace, be ready for war.

We might have remained silent, and left to heaven to mete

out the punishment due to the offence; but in looking around

us we find ourselves surrounded by a young wife, infant daughters

and affectionate sisters. And it is on their account that we

fear the poison of calumny. The least contact with this Minister

of the gospel would have made him our [2/3] enemy for ever; too

easily would he have read in out eyes the contempt which his

deeds have inspired us with, not to find in our own family his

first victims, well knowing that to be the surest mark to our

own heart.

It would consume too much time to convict by discussion this

hydra-headed priest, it must be done at a single blow, and perhaps

in this instance we are the humble instrument of heaven to punish

here on this earth this impious offender, even upon the very

spot where his crimes have been perpetrated.

Strong in our conviction, satisfied with our own motives,

and persuaded that we perform a duty however painful, we commence

the attack. We fear nothing from the accused; although to others

he appears so formidable. The culprit when unmasked will be a

corpse that no galvanic power can revivify.

To Mr. Verren we wish neither death, nor even a temporary

loss of liberty; we desire neither fines, damages, costs nor

venal compromise, we covet not the gifts that fortune may have

favored him with in this country. Let him leave a community in

which there can be no peace for him, and we will forget that

he has even for a moment engaged our attention. He too has a

family, and if a particle of shame remain, he can decide which

of us is most to be pitied, and which of us has best fulfilled

the obligations imposed by his position in the world.

[4] Those who are truly religious can in no wise be affected

by the merited punishment which we inflict upon Mr. Verren; since

men of probity cannot be scandalized by the conviction of a villian.

We entirely disregard the clamours of the weak and the wicked

that may assail us, well knowing, that

Fools since Adam are always in majority.

Had Mr. Verren but followed his vicious course in secret,

we would never have raised even a corner of the curtain which

concealed him from the world; but the baseness which he has exhibited

in his epistolary slanders, and the abyss of grief into which

he has plunged some of his victims have convinced us that it

is not sufficient to shun his society to be shielded from his

weapons, and it is on this account that we have so much dreaded

him for ourselves, our family and our friends. A snake in the

grass, the brightness of day will strike him with the inertia

and the inability to do evil; we leave with him only the desire

of being good, and the power of practising virtue; let him do

so and we are satisfied.

New York, December 25, 1839.

P. Barthelemy.

PREFACE.

Fuit istâ quondam in hâc republicâ virtus,

ut viri fortes acrioribus suppliciis, civem perniciosum, quam

hostem acerbissimum coercerent. Cic. Catilinaires.

In writing his tartufe the author intended to portray, and

in fact has portrayed one of the vices which characterized the

age in which he lived; it is not a single individual that Molière

has exposed on the stage; but it is the moral infirmity which

he there exhibits, the more to be feared since it derives its

power from the seductive as well as deceptive appearances which

it assumes.

Fallit enim vitium, specie virtutis et umbrâ,

Cum sit triste habitu vultuque et veste severum. Juvenal

[6] A low hypocrite is not to be dreaded, but who can defend

himself against the perfidious designs of one whom our manners,

our religious faith and our social habits recommend to our confidence,

our respect, and our veneration? The laws of all nations punish

those who taking advantage of their position or of our confidence,

appropriate to themselves all or a part of our fortune; but what

laws can brand the hypocrite, who under the mask of religion

gains access to our family fireside, and becomes acquainted with

our private affairs in order to pander to his own passions, who

dishonors the conjugal tie, and instead of leading our daughters

in the path of virtue deceives and ruins them!

Scire voluut secreta domûs, atque inde timeri.

Our laws cannot reach the dark deeds of the hypocrite, because

the mystery under which he acts secures to him almost certain

impunity; and too often the cloak under which he has imposed

upon our credulity, becomes the shield behind which, he contemplates,

the pangs of his victims without fear.

But if too often the apprehension of false scandal adds to

the insufficiency of the law to chastise the wicked, there still

exists in our institutions an efficacious way in which to unmask

the vice and deliver up the culprit to the severest punishment

which public opinion can inflict, we may repeat with Cicero,

"The [6/7] more elevated in public esteem he who tramples

under foot every virtue, the more severe will be the punishment

which that public will inflict."

The duty which our position imposes upon us, is far more painful

than that which the genius of Molière created for him.

To him was given full liberty to mix his colours, to shade his

tints, to sketch his portraits and to draw his characters; his

imagination has afforded him a large field which he could dispose

of at will, to suit his taste and talents; from such materials

he has constructed an imperishable work, convinced by his art

the necessity of drawing his pictures true to nature. Horace

could haze told him:

Aetatis cujusque notandi sunt tibi mores.

As to us, our task is the reverse, since our hero has gone

so far beyond what might seem true, that although compelled to

respect the truth of his deeds, we feel ourselves with difficulty

restrained to the simplicity of mere narration.

Truth does not always wear the appearance of truth.

The vice of the age of Molière in being personified

by our hero, has been so perfected that the dramatic hypocrite

is only a rough sketch compared with our reverend gentleman.

More fortunate than Molière we have only to brand upon

the forehead this [7/8] beast of prey: it is not a corrupt majority

that we attack, it is only one of those men

Fel in corde, fraus in factis

who are luckily isolated, and without other authority than

an assumed position. It is sufficient to tear from him his mask;

society will be avenged by the voluntary ostracism which he shall

condemn himself to, and our merit though small, shall be to have

told the truth. Is this then so hard to speak that we give ourselves

credit for its utterance? No, it is a duty and it shall be fulfilled.

It is not only in the name of religion betrayed that we have

entered upon this publication; but it is in the name of what

every man holds most dear and sacred, whatever may be his creed

or the doctrine which he professes.

It matters not, whether we be or be not the countryman of

the man whom we deliver up to public vengeance, whether we be

his friend or his confident, his colleague or his accomplice,

our pen has written the truth, perhaps not the whole truth, but

certainly no more; we perform a duty which we owe to society

and feel to be due from us as a citizen, a son, a husband, a

brother and a father; being bound by such titles to protect the

domestic hearth.

[9] The American law gives the right to all to apprehend an

offender, and we are ready to abide by the maxim

Quo quisque peocat, in eo punietur.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH.

Anthony Verren was born at Marseilles, of parents who were

any thing but wealthy. His education, however, was not neglected.

He gave early signs of his intelligence, whilst his amiable dispositions

and his precocity gained him the esteem of his teachers; but

thrown too early into the world where he could only figure in

the shade, he was obliged to look out for a more appropriate

sphere in which his natural vanity could be gratified.

The military exploits of the empire raised the first shouts

of glory which reached his ears; but he was too young to follow

the stream upon which all the youth of France had embarked, and

he was naturally too timid to take pleasure in the rude chances

of war. Verren therefore shaped his course in a different direction.

[11] Having paid considerable attention to natural science

he was induced to adopt principles that are far from being in

perfect harmony, either with the doctrines of the holy scriptures

or the dogmas of Rome. At this period he inclined to an opposition

at the head of which, after the philosophers of the eighteenth

century, stand our cotemporary savans. To maintain and demonstrate

the indestructibility of matter was an undertaking not perhaps

beyond his belief, nor foreign to his literary pursuits, but

it was one which required both application and perseverance,

and to neither of these can Verren lay claim. The world possessed

for him great charm; the aridity of study, and the length of

time it would require to gain a reputation together with his

want of fortune prevented him from seeking it through this channel.

The restoration was inclining to favor the old abuses of the

Holy Chair. The chance was a good one, and he had the good sense

to seize it. The claustral life not agreeing with his natural

disposition, he became a simple dayscholar at the Academy of

Geneva, where without any very severe academical examination

he was content to receive the simple ordination of the reformed

faith. Thus do we see him entered into orders, not from choice

nor conviction, but actuated by a necessity or ambition, as one

takes a trade or chooses a profession.

[12] A. Verren began his new career at Ferney, a place which

has been rendered famous by Voltaire. Pastor of the village he

soon became its idol. The turrets, the oratory and the groves

of the chateau have been the witnesses of many an act of prowess

which had any thing for its object, but the edification of his

flock, but luckily for him they are silent and discreet. We too

shall remain dumb, and shall not describe the scenes in which

the hero whose praises we chaunt was a fortunate and indefatigable

actor. But there is an end to human felicity, and Mr. Verren

is a living witness of the truth of this remark. Quitting his

parsonage he left open a door which had been cut in the enclosures

of the chateau at the instance of affectionate solicitude, in

order to shorten his distance; his successor may perchance avail

himself of the same passage; for although every road takes us

to Rome, the shortest is always the best in intrigue as well

as in geometry.

He abandoned Ferney, church, chateau, parsonage, groves and

penitents, in fact every thing to come to New York, influenced

by the same uncontroled ambition which took him from Marseilles

to Geneva, or perhaps lead by an invisible hand to become a great

and terrible moral example.

He is at last in America, a world new and unknown to him,

what brought he with him? A mind and a conscience equally flexible,

a love of scandal, a bright varnish of knowledge, genteel habits,

acquaintance with the world, and a prepossessing appearance.

Quid dignumtanto feret hic promissor hiatu?

His first step was to apostatize and submit to a new ordination

at the hands of a bishop, thus annulling the sacred investure

of Geneva and condemning the creed he had professed at Ferney.

At scarcely twenty-five years of age he had passed from materialism

to calvanism, and thence to episcopacy. Is his last confession

the most sincere?

Admitted into the most distinguished circles he was soon noticed

by them, and not long after received a call from the French Episcopal

Church, where he made every effort to develope the resources

of his mind and thus add to his personal influence the graces

of his person. He wished to appear a saint that the fair sex

might consider him an angel. He succeeded. He made a sensation.

His sermons are neither too rigid nor too wordly; he knows how

to be new without being an innovator, and without great superiority

he is above all acquainted with the art of being listened to.

His voice is soft, conciliating and persuasive; through it his

congregation began to unravel the pure and holy doctrines of

the gospel, which being illustrated [13/14] by appropriate examples,

are less austere and formidable than are generally received.

He is another Orpheus; every thing comes as he tunes, the

marble moves, it stirs, it takes form: for him is erected at

great expense a temple, a beautiful model of good taste, luxury,

elegance and classical beauty, How proud is he under that sacred

portico! How pompously arrogant in the middle of that nave and

under that cupola so skilfully constructed; how spiritually proud

in that pulpit from which he gives law to an auditory that abandons

itself to the most sacred of prestiges! He is no longer the humble

disciple of Jesus Christ preaching in the temple; but the illustrious

pontiff fulminating his decrees. Verren is at the present moment

truly great, noble and seducing, the most happy perhaps which

he will ever enjoy in this world. This enviable fortune, this

realization of his dreams when in Europe he will devote not to

the advancement of religion, but to quench the fire that courses

in his veins.

The pulpit is like an ethereal circle, from which as a vivifying

star he darts his beams upon the sweetest flowers. The parterre

at his feet [14/15] is composed of the most lovely fair of New

York, who are all eager to listen to the new preacher. The temple

becomes a theatre in which vocal music rivals instrumental harmony

in its effects and talent; thither are the crowd attracted:

Sic ruit ad celebres cultissima faemina ludos.

Verren attaches himself to his parishoner not to edify but

to mislead them. The impostor uses in their presence all the

refinements of flattery, all the seductions of eloquence: behind

them he expresses the utmost contempt. If he praises the delicacy

of their graces, he afterwards frees himself from the restraint

which for a moment he has submitted to.

A fair lady whom he praised to the utmost, whom he has declared

to be worthy the first crown in the world, he soon after parodies

as a necessary ornament of a museum of osteology; he fancies

himself witty when he is only impertinent, repeating the pun

in this verse,

"Mon esprit en secret l'appeloit à règner."

[The pun is on the pronunciation of the last word, "à

règner," which cannot be translated nor understood

in English.]

[16] Such are his abusive epithets against the American ladies,

except when he attacks their manners, when he is far more cruel.

The indecent language which Mr. Verren uses in his confidential

communications would be an impropriety that we would not allude

to if that were his only fault, but our task is to show him in

his true colors to the people of New York.

In the documents which we have collected for this publication,

are contained a large number of facts and anecdotes relating

to many highly honorable and respectable families; these we have

suppressed as giving unnecessary pain to those who are the subjects

of them. We desire to create no scandal, although much may flow

from our revelations, but this is not our affair. We shall indite

nothing that is not strictly necessary for our object: to unmask

the impostor.

We have also neglected to report many intrigues of the vestry

room, many low and despicable tricks which he has directed, in

order to defect the nomination of such a man and elect another,

or to change and render null decisions that were contrary to

his views, to cause to be adopted his own estimates for building

[16/17] improvements, repairs, embellishing of the church, or

a clause in the lease of such and such property belonging to

the congregation, &c. &c.

All these have been laid aside by us, although it would be

very easy for us to take advantage of these transactions and

represent Mr. Verren rather as a cunning broker, than an upright

and disinterested pastor; but although he be culpable in these

respects it is not our intention to attack him on these points.

We have exhibited him elsewhere, or rather every where, except

in the vestry room and in his own house, because there we consider

him beyond the jurisdiction of the press.

In conclusion we sincerely express the hope that the two-fold

sanctuary which we have respected, may be for him a safe asylum,

where he may reconcile himself to his duties, conceal the notoriety

of his faults, and give to his young family at least, the example

of domestic virtue.

CHAPTER I.

AT HOME.

This chapter will be the shortest of all those we have devoted

to celebrating our hero. We shall be particularly concise, not

because materials are wanting, but because we wish to remain

faithful to the salutary maxim which Mr. Royer Collard has thus

expressed at the tribune of the Chamber of Deputies, when the

laws of the liberty of the press were under discussion: "Private

life should ever be sacred." Inviolable in effect shall

that of Mr. A. Verren be to us, whom we shall not attack in his

domestic circle; but in his character of a public man he belongs

to us from [18/19] head to foot. We have the right, and we intend

to use it in its greatest extent, to scrutinize his conduct,

to interrogate his deeds, to search his thoughts, and to expose

his actions whatever they may be. We do not think, however, that

the yard of his house belongs to his house, and we have dedicated

a chapter showing what takes place there habitually; beyond this

all the interior of his house is held sacred by us.

The characteristic circumstances of his marriage with one

of the Misses Hammersley are not yet effaced from the memory

of the public; they would have believed that love had entwined

with his myrtles the chains of Hymen. Be it so! we have nothing

to say about it, and leave to others the task of relating the

delights of that new Ariadne.

But before that future author, and before us Horace has said:

Sic visum veneri; cui placet impares,

Formas atquc animos sub juga ahenca

Soevo mittere cum joco.

Semper habet lites alternaque jurgia lectus,

In quo nuptia jacet; minimum dormitur in illo.

Sed notat hunc omnis domus et vicinia tota,

Intiorsum turpem, spcciosum pelle decorâ.

CHAPTER II.

Nihil est tam voluore quam maledictum, nihil facilius emittitur,

nihil citius excipitur, nihil latius dissipatur.

Vires aoquirit eundo.

Slander, My Lord, slander, there is always some of it that

sticks.

Calumny!.....I have seen the most respectable people nearly

crashed by it.

From Virgil to Beaumarchais and from the author of the marriage

of Figaro to our Reverend hero, calumny has been considered as

the most [20/21] dangerous and infallible weapon; it is to the

wickedly disposed what poison is to the murderer; it has struck

its victim before even its existence is suspected, and when it's

presence is revealed, it is already too late; the deed is done,

it progresses, it propagates itself, it corrodes, it destroys

and annihilates the being- it has attached itself to. Baour de

Lormian and before him J. B. Rousseau have left us fine odes

and beautiful verses upon calumny, but what can the thoughts

of genius teach us compared to the dark deeds of the Reverend

Verren? What we are going to relate is not the mere creation

of our imagination, we have the original documents in our hands

to confound the author of the anonymous letters if he dare, or

if he should have the impudence even to attempt to deny the facts.

In another chapter will be seen the advantage Mr. Verren derived,

not from his personal en' dovvments alone, but from his so honorable

position, to chose the objects he judged proper to satisfy his

passions. By and by we shall show that he is not scrupulous as

to age or color; like a gay cavalier he likes to sing wit Joconde,

To whatever clime I chance to go,

To change my manners well I know.

[22] Although prince of the vestry, he has met with virtue

which has withstood his arts. If he fail in his attempt?, if

the first hints of his declarations be received with an eloquently

silent contempt then his heart opens to the sentiment of revenge;

hatred springs up and every mean is used which can satisfy the

imperious want to which he is a prey; woe in this case to whoever

has provoked his ire!

This man, however, who diverts himself at leisure with the

innocence, the tranquility, reputation and fortune of others,

is not alone the slave of his own vile passions, but becomes

an easy tool for the companions or the accomplices of his bad

actions to move at their will. It may be said that to him the

opportunity of doing evil is good fortune. It is sufficient to

indicate it to him, and he becomes active, he overturns all the

ground under his feet to reach and wound his victim, it matters

little whether he has cause of complaint against him or not.

In more than one instance into which this unhappy propensity

has led Mr. Verren, he could not explain even to himself, much

less confess to others the real secret motive of his attrocity.

The devotion he has for vice and evil render him their victim;

for he [22/23] delivers himself up to this inclination with a

delight that would seem to belong to delirious fatality. We see

him, we judge him with the documents now upon our table; we see

him blindly assisting the petty jealousies of a woman, of whom

he believes himself master because he has rendered her guilty,

going far beyond what she solicited from him, and after having

entered in a bad path, following it till he becomes ashamed of

his own excesses, but always too late to repair the evils he

has produced, to wipe away the tears he has caused to fall, to

assuage the anguish he has created.

We therefore, in this chapter, attempt a task which is above

his power of self-control.

Among the many facts which we might cite, we select the following,

the truth of which is so cruel that it suffices to portray Mr.

Verren, at the same time it permits us to render to the person

who has been his victim, a public and just reparation, as well

to procure for her some repose from the cowardice of her invisible

enemy, which for a long time has pursued her almost to destraction.

Miss * * * * whom we mention with as much pleasure as respect,

came to New York, that she might devote her time to tuition.

Her talents, [23/24] her education, her virtuous conduct, the

amenity and urbanity of her manners, had gained for her the esteem,

the friendship and good wishes of the most distinguished families

in the city.

Introduced to the pastor of the French Episcopal Church, Miss

* * * found in Mr. Verren a minister, who laying aside all pedantic

austerity, showed himself by the instruction which he imparted,

and the gracious manner in which he treated her to be worthy

of the high mission entrusted to him.

Our Reverend hero is himself under that secret influence,

so full of those charms which we experience in the society of

an intelligent woman, who is lively without coquetry, and who

talks sensibly without wasting her time in idle prattle. He invites

her to come to his church, and although the worship is different

from her own, the desire of hearing French preaching induced

her to accept the invitation.

Mr. Verren who is fond of busying himself with other people's

affairs becomes soon well acquainted with the position of his

new acquaintance; he offers his services with the greater eagerness,

because his only interest is the [24/25] satisfaction he feels

in being the protector of true merit; but his efforts, if sincere,

are superfluous: his PROTEGEE has friends more happy to serve

her.

An occurrence insignificant in itself allows Mr. Verren to

find suitable lodgings for Mademoiselle. These lodgings make

part of a handsome house, engaged by the Reverend gentleman for

the husband of a young lady, handsome and adorned with natural

wit, that, in order to shine, had nothing to borrow from a memory

adorned with serious and useful study. The daily contact of two

female characters so little congenial could unavoidably bring

about no other than a sad result. The one polite, talkative without

freedom, disdaining an easy victory, content to let her superiority

appear without deriving advantage from it; the other good-humored,

gay, playful, at her ease and in her sphere whenever the conversation

was within her comprehension, but embarrassed, uneasy, humbled

when questions of moral philosophy were treated of, or where

the discussion led by people of talent embraced history, literature,

science or politics. Very familiar with the fluctuations of prices

in the market and with domestic chit-chat, but unacquainted with

any other subject, the mistress of the house [25/26] at first

only ruminated in silence on her conscious nullity; she then

grew uneasy and manifested ill-humor without explaining the cause;

there ate avowals against which self-lore revolts. Then after

many endeavors to punish and humble her whom she could not rival

she framed in the dark her schemes of petty vengeance.

Mr. Verren was naturally the person in whose bosom she deposited

part of her sorrow. He listened like a good pastor.

While the storm was rising at a distance, Mademoiselle * *

* * had ceased going to hear the sermons of Mr. Verren, perhaps

not because she had already perceived a falling off in the merit

of orations pretty well written and not badly delivered, but

because these orations, or sermons if you will, always supported

a doctrine which she could not acknowledge as hers; this circumstance

so simple, so natural, so justifiable in her condition, was perfidiously

interpreted to the Reverend gentleman, and disposed him blindly

to favor a resentment, the secret of which was unknown to him,

but with which he from this instant indentified himself with,

as if in embracing the cause of another he was revenging himself.

He went therefore far beyond what the greatest jealousy would

had have carried the handsome companion of his friend.

[27] About this period, Mr. Verren who never loses sight of

his wordly interests, wished to settle Miss * * * * in some business.

He, however, met with a prompt refusal, which he might have avoided

by a little tact and management. He should have been conscious

that the learned character of his calling, forbade him from entering

into any operation that might become a broker.

He should have kept his importunity for solicited service,

and the more trouble and anxiety that he gave himself to explain

the sureties and advantages of the money that he coveted, the

more he lowered his dignity. In this proposition prepared with

studied care, and for which he seemed to have invoked the shade

and talents of the unfortunate Vatel, Mr. Verren was more pressing

than the apparent motive required, and the positive refusal he

experienced opened his heart to a series of emotions, which vigilant

jealousy worked, and incessant and inquiet rivalry improved with

advantage. [A celebrated cook, whose suicide is mentioned in

Madame de Sevigne's letters.]

Mr. A. Verren believed himself despised, he persuaded himself

that he was so, so powerful is conscience which leads us to imagine,

that others see through our baseness. He despised! he will have

satisfaction, but in his own way. Quick! ink, paper, a pen and

even pencils, he must write lies, [27/28] and frame outrages.

Yes, reader in truth, our Reverend divine draws not well, nevertheless

he loves caricature; if he knew not how to form an eye, trace

a nose or a mouth, to make amends he excelled in making other

features. Should he ever attempt to edit the popular work of

Dr. Tissot, for the use of those arrived at the age of puberty,

believe us he would reserve for himself the care of the plates,

and he would load it with as many as the text would allow.

Whilst mending his pens and his pencils, and thinking what

he shall do, a mouth that he likes for more purposes than as

a communicator of thought, informed him that Mademoiselle * *

* * being in company with several other ladies who had expressed

themselves on the very gallant manners of the Reverend gentleman,

said, "If he passes for a libertine he does not prove himself

much better than the generality of his sex."

There was nothing malevolent in this simple remark, on the

contrary, we may readily perceive in it a frankness and natural

goodness of mind. For in not excluding Mr. Verren from the generality

of men notorious for their subjection to the passions, she cast

upon him no animadversion, she sought on the contrary to make

him participate in that absolution, that secret amnesty of which

pretty women are no misers in such circumstances. But though

innocent [28/29] in itself this report roused the demon which

inspired him. The word libertine burst upon him like a

ray of light, 'tis the electric spark that fires his imagination,

and vivifies all the erotic resources it possesses. Before he

was uncertain as to what plan of vengeance to pursue, but that

word caused every nerve to thrill. We are told that Achilles

disguised as a female in the court of Lycomedes, betrayed his

sex at the sight of a sword which the cunning Ulysses disguised

as a merchant, exposed to his view among the articles of the

toilet. Such was the word libertine to our Reverend gentleman.

He knew where Mademoiselle * * * was well received, whence

her resources, where her friends and protectors, 'tis there the

blow will be struck,

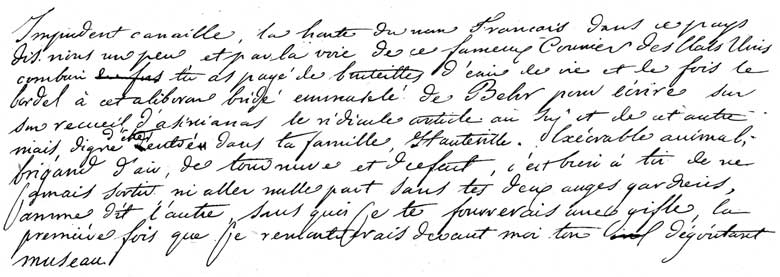

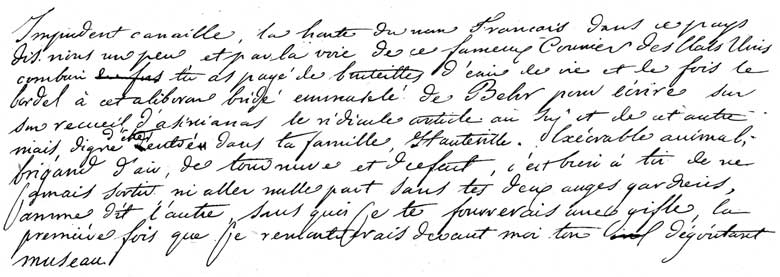

He writes to Madam B--------, Madam D-------- and Mr. C--------several

anonymous letters and prepares others, the originals of which

in his own hand writing are in our possession. The respect we

have for ourselves and readers preclude the possibility of our

quoting them. Never have Aretin and A. Piron in the shamelessness

of their poetical rage pictured such obscenities. The sweeping

imputations contained in these letters, are clothed in so much

epistolary form, that a master hand is discoverable in every

line. The calumny increased and extended itself.

Quelque grassier qu'un mensonge puisse être.

Ne craignez rien; calomniez toujours:

[30] Quand l'accuse confondroit vos discourse,

La plaie est faite; et quoiqu'il en guérisse,

On en verra du moias la cicatrice.

Few persons have given credit to the advice and confidences

of the anonymous writer; some of them mentioned the subject to

Mademoiselle * * * others were less candid, but their reserve

did not deceive that lady who had too much knowledge and experience

of the world, on the contrary it convinced her that she was the

victim of an unknown and powerful enemy. She was so cruelly grieved

that she was obliged to renounce an establishment that could

not have failed to have prospered under her skilful management;

if we had not revealed it, she would be even now ignorant of

the source whence the calumny sprung; but we have fulfilled a

duty which lays her under no obligation to us. We are sufficiently

rewarded for our efforts in the belief that we have restored

to her that peace of mind she so much needed, even amid the consolation,

kindness and attention bestowed upon her by the numerous friends

by whom she is surrounded.

CHAPTER III.

De votre fête hymen voici le jour

N'oubliez pas d'en avertir 1'amour.

Madam *** had just lost and interred her husband. An afflicted,

but an economical widow, she did not like the extravagant Artemisa

erect over the ashes of the departed, a costly monument to speak

her grief to posterity; but secretly and in solitude mourned

the friend she was never too see again in this world of sorrow-

Nothing incites more to sadness than the self-imposed retirement

of an affectionate and recently wounded heart, but this sadness

which for a time humors and excites itself, soon becomes frightened

and astonished if not wearied at the isolation in which it finds

it is plunged. Between society and affliction there is a gulf

which the former [31/32] never cares to fill, (so little are

we affected by the sorrows of others) j but which the mourner

for her earthly happiness is forced to pass as soon as possible.

Like a pouting child we see the new made widow seeking a reconciliation

with the world; as between the tomb and the ball-room the altar

intervenes, so the church is commonly the path by which she seeks

to reach her object. It is at the altar we breathe the sweet

vow of unalterable love, and it is there we seek impunity for

a perjury yet more sweet. It is in the bosom of the priest

(the mediator as we all know between temporal and heavenly power)

that we pour our sorrows, in his knowledge we look for consolation,

and the heart is then disposed to open itself to the words of

peace, of pity and of hope.

Our modern widow of Ephesus had arrived at this chapter in

the ordinary events of life when she applied to Mr. Verren, not

as the fine gentleman filled with sympathy for the sorrows that

consumed affectionate hearts, afflicted with attractive charms

and twenty-five summers; but the minister of that God who said

to the woman taken in adultery, "Go and sin no more."

The parties met to speak of another world. Mr. A. Verren a

truly erudite connoisseur, discovered with his eagle glance the

cause and depth of the evil. He pointed out a remedy, but the

widow started [32/33] as if the proposition would burst the cerements

of the grave and call her late lord before her. She trembled

from head to foot, and murmured out her fears of the vengeance

that heaven inflicts upon the perjured. The smiling pastor like

a second tartufe said to her:

Je puis vous dissiper ces eraintes ridicules,

Madame; et je sais l'art de lever les scrupules.

Le ciel defend, de vrai, certains contentements,

Mais on trouve avec lui des accommodemens.

Selon divers besoms il est une science,

D'étendre les liens de notre conscience.

Et de rectifier le mal de l'action,

Avec la pureté de notre intention.

De ces secrets, Madame, on saura vous instruire,

Vous n'avez seulement rni'a vous laisser conduire.

-----------------------n'ayez point d'effroi,

Je vous reponds de tout, et prends le mal sur moi.

[I can satisfy those ridiculous fears of your's, my dear,

and easily rid you of those scruples. 'Tis true, heaven forbids

us certain pleasures, yet it is allowed us to compromise it's

decrees. There is a science which permits us in some cases to

loosen the ties of our conscience, and to purify the evil of

the action, by the purity of the intention, We will teach you,

my love, these secrets, permit us only to direct you. -----------------be

not afraid, I am answerable for all, and take the evil upon myself.]

Like a submissive lamb Madame * * * heard the shepherd, but

as yet did not surrender. She was divided between her future

happiness or her earthly repose; the world is a severe judge,

and exposure a death blow to the woman who once forgets herself;

although she could not refute the passionate language of her

insiduous director, she yet obeyed the [33/34] "still small

voice" of a heart formed for virtue, and manifested the

fears she could not express.

Verren determined on a last effort. The ground upon which

he found himself engaged and where he wished to triumph, was

no longer that of Duane Street, (see ch. 5). Madam * * * * had

gathered from her marriage an experience which rendered laughable

all the attacks of our skilful engineer who sought to surprise

her. He changed his tactics as easily as he had apostatized--so

elastic was his conscience!

Minister of the Most High, he dared to promise future pardon

for all the sins of his penitent; on this side she was satisfied,

but Verren is unable to preserve her from the censure of the

world; that is of little consequence to one determined on success--

and again invoking his sacred character he proffered pledges

of a different nature.

Les gens comme nous brulent d'un feu discret,

Avec qui, pour toujours, on est sûr du secret.

Le soin que nous prenonsde notre renommve,

Repond de toute chose à la personne aimée

Et c'est en nous qu'on trouve, acceptant notre coeur,

De l'amour sans scandale et du plaisir sans peur.

[People of our garb love with discreet ardor, with us you are

always sure of secrecy. The care we take of our reputation, is

a security for her whom we love; and in accepting our heart,

she is sure of having lave without scandal and pleasure without

fear.]

Madam * * * * knew not what reply to make; she [34/35] sighed,

shed a few tears, glanced upon the past and leaving the present

and future to the care of her spiritual director, closed her

eyes in voluptuous languor upon the abyss that opened beneath

her.

These secret interviews were frequent. After so long a widowhood

the lady was greatly in want of a pastor to purify her soul,

and he was soon successful in quieting her fears; if some peeadillbes

remained un-pardoned they no longer disturbed her mind, had not

Verren said to her, yea repeated it a hundred times

Je vous réponds de tout, et prends le mal sur moi!

Behold our widow at last consoled, and could we believe

the promises of the Reverend gentleman, Magdalen would not be

the only pretty sinner admitted to the dwelling of the blessed;

but the terrestial happiness in which he made her taste graces

all divine, hastened to load the lady not less than her inconsolability.

Mr. Verren who was not a widower, was obliged to divide his cares

and his consolations, and often to quit the widow for his conjugal

obligations, and sometimes to neglect even these for his pastoral

ones; it was too much for him, and notwithstanding all the holy

fervor which the worthy [35/36] Reverend possessed, the desire

of self preservation inspired him with the idea of advising the

half consoled widow to re-enter the married state. The idea was

original coming from him, notwithstanding it was perhaps the

idea of a step necessary for both. And setting himself at once

to find out the happy legetimate successor of the departed

husband, his eyes rested upon a good easy man, honest at heart,

but rather ill-favored. This, however, was no bar to the affair;

had not Venus Vulcan for a husband? And as the husband elect

had but like Vulcan a physical imperfection and no other attribute

of that divinity, the invisible net was not to be feared.

The rest may be guessed; Mr. A. Verren is a cunning man ....

occasionally.

The altar was again decorated for the pretty widow; if custom

had deprived her of the plea" sure of carrying the virginal

bouquet; if the classic sprig of orange flower did not ornament

her waist, her brow was not less calm, her step less timid, her

glance less angelic, nor did she enjoy less the sweet tranquility

of heart. Her peace was made with heaven; she has obtained a

tender absolution from the holy minister who had probed her heart

to the bottom, and who received [36/37] once more from her ruby

lips the sacramental YES, which this time, however, he inscribed

on his official record. Relations, friends and acquaintances

all united, and met in the banquet hall, glistening with the

light of a thousand tapers, which soon resounded the steps of

the happy guests.

De votre fête, hymen, voici le jour;

N'oubliez pas d'en avertir l'amour.

Mr. A. Verren in his quality of officiating minister occupied

the place of honor; the husband of his convenience smiled upon

him with gratitude, and Mr. A. Verren who neither could nor wished

to be behind hand in the return of this sentiment with the good

man, smiles in his turn. His words were addressed to him, but

with his foot he interrogates his consort, and by the natural

consequence of this communication, the eyes of the lady sparkled

in time with his foot to sing sotto voce

"De votre fête, hymen, voici le jour;

N'oubliez pas d'en avertir l'amour."

Cupid well armed was upon his guard, and the happy, blind

and confiding husband thanked his predecessor for not having

carried away all his treasures with him.

[38] The immoral and criminal duplicity of our hero was not

checked on so good a path, it remains for us to relate a final

trait, that reveals at once the character of the man.

We have just seen the entire oblivion of every principle of

a husband, minister and friend. We are going to show the interested

and basely covetuous lover; for it is again by the aid of anonymous

letters that he seeks to gratify his shameful propensities.

Commercial relations called the husband to England, his wife

was to follow him. Separation became painful to her who abandoned

on the American soil, the cold remains of a man who she had much

loved, and likewise the mortal coil of one still quick, who in

the name of heaven had made her taste so many earthly pleasures.

Oh! to be seperated from this one, to quit him forever while

yet quick, became for her a bitter and poignant sorrow, what

a void would be left in her heart! They could not correspond,

prudence forbade it, they dared not ask the consolation! this

resort gives to affectionate souls, they provided themselves

with another.

[39] "L'art d'écrire, cher lecteur, fut sans doute

inventé

Par l'amante captive et l'amant éloigné."

[Heav'n first taught letters for some wretch's aid,

Some banish'd lover, or some captive maid--Pope.]

But the art of painting in minature no doubt owed its existence

to love, which though widely separated from its object, prudence

deprived of the power of writing. Features faithfully copied

sooth'd the pains of absence! We love to look into eyes which

are always lovingly opened upon us, to place in a beautiful mouth

the expression of tenderness which have so many times sounded

in our ears; it was then to this unequivocal witness of affection

our young lady had recourse to call to the mind of the holy lover,

the remembrance of such an affectionate parishoner.

The portrait painted by a skilful hand was enclosed in a rich

medallion, in which was likewise inserted a lock from those long

and beautifully arrayed tresses that Verren loved so well to

contemplate, floating over shoulders of alabaster worthy of the

chisel of Praxiteles. In those delicious moments which he chose

to recall to his penitent the life, the adventures and exaltation

of Magdelen: mercy to every sinner.

[40] The medallion was a valuable present, not only from the

associations which enshrined it, but likewise from the workmanship

and the cost of the metal which protected its fragility. The

rich and delicate love, the ingenious and disinterested heart

of a lovely but sinful woman--all that can mitigate severe censure

was reflected in this truly feminine attention, there was a poetical

tenderness in this parting gift; it was however all lost upon

Verren. He weighed the gold in his usurious hand: he put side

by side the raven tress and the ivory, and judged that all would

not pay his fees as officiating minister at the nuptial ceremony

of rich people.

As he should have blushed.... No! we deceive ourselves, the

hypocrite knows not how; we would say that he should not have

dared to have asked a compensation for his services, from a man

whom he constantly caressed as a friend, and who feared to wound

him by offering a mercenary reward for a marriage forwarded by

himself, A. Verren wrote two anonymous letter?, the first was

without effect; the second ran thus and was addressed to the

too confiding husband. "My friend, at a small party of good

company [40/41] where I was a few evenings since, you were the

subject of considerable conversation. Every one expressed much

surprise that you had not yet satisfied the minister for his

trouble. They said, how is it possible that a man well born,

of quality and who lives in good style, has not yet......:...

surely it cannot be, we cannot believe it............it belies

the good opinion we always entertained of him.........he lowers

himself, &c."

Circumstances made it appear possible that these letters were

written by Messrs. B. and E. although in rather a silly manner.

Such, however, was not the case. The lady only was not duped;

it is difficult to deceive the penetration of a woman who knows

us as well as the lady in question knew our Reverend gentleman.

Vexed and indignant with her base and unworthy director, she

took a bill of twenty dollars and presented herself at the house

of Mr. A. Verren, to whom she hastened to pay the debt in question,

with as much ease as if nothing had ever passed between them,

after which she handed for his inspection the anonymous letters

received by her husband. Verren was obliged to peruse them under

the scrutinizing eyes of a woman whose feelings he had wounded,

and who was forced to despise him, to whom she had sacrificed

all [41/42] that a virtuous woman holds most dear. Her looks

but too plainly expressed her feelings. Verren had no excuse

to make; they parted coldly: but the charm was broken, and he

had rendered it impossible that a single honorable thought of

himself should again dwell in the heart of a young, spiritual

affectionate woman who seemed fashioned by the hand of love itself.

CHAPTER IV.

L'hypocrite en fraudes fertile

Dès l'enfance est pétri de fard,

Il sait colorer avec art

Le fiel que sa bouche distile.

Et la morsure du serpent

Est moins aigüe et moins subtile

Que le venin caché que sa bouche répand.

Every honest man loves to do good. The sweetest and most self

satisfied feeling of which we are capable, is that of having

relieved the misfortunes of others. Charity is one of the predominant

virtues of Christianity, and is so justly considered as the foundation

of all religion, that ministers are more particularly called

upon to exercise its duties. Thus we [43/44] often see pious

persons devoting their fortune to charitable uses, the distribution

of which is left to the clergy; a legacy received with gratitude

which enables them to distribute alms with a discernment that

doubles its value. To give is generally easy; to give well is

always difficult.

Charity and beneficence are sister virtues but never rivals.

Benificence has founded establishments where the infirmities

of this life are solaced without distinction of age or cause:

hospitals are open to all those who suffer physically. Charity

on the contrary is more particular in the distribution of her

liberalities, and bestows them only after enquiry. Hospitals

receive the old, the indigent and the incurable; and in the world

the heads of the church whose office it is to carry hope and

consolation to the bosom of afflicted families, become naturally

the best judges that a generous heart can employ to give properly.

Since the foundation of the French Episcopal Church in New

York, a special fund had been consecrated to certain acts of

charity, and for a long time the pastor was deservedly the only

distributor. This power so honorable to him who was endowed with

it, seems nevertheless limited for Mr. A. Verren to a simple

official formality. It might be thought perhaps that several

hundred dollars left at his disposal to be distributed according

to his wishes in [44/45] small sums, became for him full of embarrassment

which augmented in consequence of the number of miseries which

he had to relieve and his facility to distribute money which

it was so agreeable to give. The details of distributing alms

are now reduced to the formality of signing a check on the treasury

of the congregation, which though of the smallest amount is paid

to the person thus succored. However small the part allowed to

him in that draft of integrity, it still leaves to Mr. A. Verren

the power of exercising his despotism and of yielding to his

base passions.

For a long time the treasury of the French Episcopal Church

was opened with as much justice as precision to a family composed

of a man and wife; the youngest of which could reckon more than

sixty winters, the half of which they had passed together. Poor

trades people limited in their wishes, they lived upon the produce

of their labor. Each day brought them bread, but soon their increasing

years diminished these necessary resources, they became indigent:

accustomed to place their confidence in God and to thank him

daily for the blessings bestowed upon them, they constantly implored

in his temple a continuance of their strength and health. The

appearance of this venerable couple fixed the attention of the

founders, so in other times were Philemon and Beaucis honored

and assisted.

These good people instructed that they could rely [45/46]

upon succor so necessary to their subsistence, presented themselves

each month confidently, and with gratitude, at the parsonage

house. They considered Mr. Verren as the true minister of a God

of goodness, who did not forget them at the close of a long but

irreproachable life, nor did they even think of mourning when

Mr. Verren forgetting, that the manner of giving doubles the

value of the gift, caused them to call several times before giving

the check for the accustomed sura. Far from suspecting in the

conduct of the pastor a natural antipathy to the unfortunate,

above all to that of the aged, our old couple returned peaceably,

hoping another day to find him less occupied. Mr. Verren does

not like to trouble himself where he has no personal motive,

and as there was nothing flattering in the necessity he found

himself in of receiving, hearing and serving these old people,

poor and isolated in the world in which he was so fond of moving

and shining, he became angry at each time he was obliged to receive

their visit. The consequence of his bad humor, was that he made

them renew many times their request without cause or excuse.

At last the pertinacity of the poor people made their presence

so irksome, as to be a kind of persecution to the unworthy rector;

they however, were far from considering themselves importunate,

since they came less to solicit than to receive what the distributor

was obliged to grant. One day his impatience broke all bounds,

his anger carried him away, and he cursed the [46/47] couple

who remained confounded, speechless and trembling, before the

apostle of Jesus Christ, who was vociferating the dreadful words

of "Go to all the devils in hell!"

Ah! Mr. A. Verren.

"Quoi! vous êtes dévot, et vous vous emportez!"

To appreciate how barbarous and cruel was such conduct for

those who were the object of it, it must be remembered that they

were very old, pious, having not only respect but even the utmost

veneration for their pastor. In the evening of life when one

foot is already in the tomb, and we are preparing ourselves to

appear before the Creator, his minister becomes for us a holy

intercessor. It is to him we open our heart and ask if we are

in a state of grace, and well prepared to render an account of

our life sufficiently long. The elder we grow, the more our faculties

become weakened, the higher we prize the words of the interpreter

of the text. It was notwithstanding in these circumstances that

the Reverend Verren in the place of consoling absolution, sends

to hell those whom God has enjoined upon him, to serve, to clothe,

to nourish, and lastly those to whom he has been ordered to give

pecuniary assistance.

[48] Troubled in heart and soul, terrified and full of tears,

oar good people departed from the inhospitable house of our small-footed

prelate, not to go where his impious mouth had sent them, but

to Bishop O---------, to whom they related their case and asked

spiritual counsel. This ecclesiastic so worthy of his high station

used persuasive, conciliating and consoling language towards

them, and sent them away more tranquil and happy. But his duty

was only half executed, it remained with him to reprimand. He

sent for the imperious and choleric Verren. Our readers may suppose

what took place between two men who worship God in the same manner.

It is enough for us to relate the new feelings to which this

conversation gave birth in the heart of Mr. Verren.

"Dieu fit du repentir la vertu des mortela,"

but Mr. Verren who has no ambition to practice a single virtue

either by inspiration or repentance, swears and promises to himself

that the old couple Barbelet, for we must give their name, shall

repent their infamous report.

The vestry of the church decided that a stipulated sum should

be paid henceforth monthly to these old people by the treasurer

without any farther [48/49] formality. Thus this allowance is

no longer occasional, arbitrary or customary; it becomes now

a vested right.

It is but just to add that by this resolution, the vestry

having authorized the treasurer to pay monthly the sum allowed

to Barbelet, they freed Mr. Verren from what was to him an insupportable

burden. But in this act of humanity, wisdom and foresight, the

vestry gave satisfaction to each party, in this way, that the

assistance allowed was too little for the wants of that poor

family, and that Mr. Verren was to have the power to augment

it from time to time by an additional draft when in his judgment

it was necessary.

The part left to his good feelings or his charily was a snare

into which his perverseness causes him once more to fall. When

we say the snare, we do not pretend to say that the snare was

intentional; but though accidental and resulting from the circumstances,

Mr. Verren had not sense enough to evade it. To the demand of

additional assistance the Reverend gentleman was deaf, or to

be exact in this simple expose of facts we will say that he listened

to the too plausible motives of the demand, that he was [49/50]

even willing to grant it, to give it his sanction, his signature,

but on a condition to which Barbelet was not willing to subscribe.

Mr. Verren is firm, he determined to persist until hunger, misery

and privation shall have procured a full and complete retractation,

worded and prepared by himself, of the complaint made to his

bishop, or till his slander may once more have been brought in

play to aid his base conduct.

Minister of the God of mercy, far from forgiving those by

whom he pretends to have been offended, he leagues himself with

the infernal deities against virtue, suffering without support

in this world, where power too often constitutes right.

It was in vain that the poor couple Barbelet presented themselves

to Mr. Verren, he fears not to require a declaration which he

knows to be a lie. Their refusal did not shake his determination;

"Sign or you will get nothing." They would not sign,

and notwithstanding the privations to which they are a prey,

during this inclement season they do not sign it. Ah! it is not

at the age of more than sixty that we begin a career of disgrace;

it is not with a flourish of a pen that we would sully a long

life of honesty. [50/51] This is what Mr. Verren would not believe:

he is not yet satisfied.

Barbelet and his wife did not cease to visit the church, although

an unworthy and hypocritical minister officiated there; they

went not for him, but for Him who sees and judges all. Their

presence was embittering to Verren. If for some there is no greater

burden than to receive a favor; for the unjust and the wicked

nothing is more hateful than the sight of those who have a right

to accuse them, so true is it that we cannot stifle the voice

of conscience.

Our Reverend gentleman determined to get rid of them at any

price, to lose sight of those whom he had dared to send where

no hope is permitted. He determined to be stopt by no means whatever,

and crime itself shall be invoked to aid him.

"Tant de fiel entie-t-il en l'âme d'un dévot?"

Anonymous letters of which he has so often availed himself,

are in this case arms not sufficiently powerful, it is necessary

to resort to perjury, but perjury clad in all it's forms. With

this view he opened his mind to a member of the vestry, he explained

to him his unhappiness, [51/52] described to him the anguish

he was a prey to, and avowed to him that he would enjoy no rest,

no satisfaction while those Barbelet were under his eyes. He

dared to entreat, to conjure, to beseech this vestry man to accuse

at the next meeting, those old people, and to declare openly

that they kept a house of ill-fame. That affirmation would be

sufficient to drive them from the temple, to forbid their entering

it, will make up for their refusal of retractation, and will

justify all his conduct towards them.

Foedius hoc aliquid quandoque audebis?

All the eloquence of Mr. Verren shipwrecked in this cause,

against a man who thus far, had been but too weak and condescending,

in making himself the confident and instrument of his bad actions;

but there is a limit where even slavish devotion ceases and to

that limit Mr. Verren had forced him. A first refusal did not

discourage him; he returned several times to the charge and became

troublesome, and even so commanding that the vestry man was obliged

to retire entirely from the affairs of the Episcopal Church,

and lastly to break off all connexion with Mr. Verren who had

become too despicable and odious in his eyes.

The Barbelets, still without receiving an addition to the

small assistance voted by the vestry, and faithfully paid by

the treasurer, a prey to a thousand little [52/53] privations,

consequent upon their noble refusal; they do not, however, discontinue

to visit the church; it is probable that it is the only place

in this world where they and the pastor could meet, because in

the next the just and the wicked have each a separate dwelling,

and our old people would not go where Mr. Verren wished they

should precede him.

CHAPTER V.

Maxima debetur pueris reverentia.

Nondum experta novi gaudia prima tori.

.......Null a reparabilis arte

Laesa pudicitia est.

Among the families by whom our reverend hero was received

as a welcome guest was the family of Mr. C--------, in Duane

Street, who expected to meet in the constant visits of the head

of the church, both [54/55] a protection and good example for

his numerous family, which consisted of a son and several young

daughters; the conversation which was varied was always of the

purest morality; this circumstance had made the presence of Mr.

Verren almost a necessity for Mr. C--------, who being obliged

to devote himself almost entirely to commercial affairs, saw

with satisfaction that he was so well replaced at home.-- His

son had just set out for the South, where he intended to remain

for some time: meanwhile the eldest daughters divided between

them the cares of house-keeping and of welcoming their visitors.

The youngest, scarcely fifteen years of age, excluded herself

entirely from society, and for this purpose had chosen as her

favorite retreat the lowest apartment in the house which looked

out upon the street) whence there was a direct entrance.

This young lady of a florid complexion, as is usually the

case at her age, was nevertheless conspicuous for the developement

of her form and the gracious contour of her person, seldom to

be seen at her tender period of life; her soul, the serenity

of which nothing had as yet troubled, was disposed to confidence,

her mind cultivated by a good education was fond of virtue, which

the natural dispositions of her heart made sweet and dear to

her; her taste for study separated her from her sisters, and

the Reversed pastor willingly encouraged her inclination for

[55/56] the retreat, expecting to take advantage of the time

stolen from their presence and superintendance. Under pretence

of religious and moral conferences, he appointed particular hours

for his visits, which, however, he took care to arrange in such

manner as to apprehend no interruption, and that their frequent

and mysterious regularity might not cause remarks adverse to

his purposes.

After having thus prepared the field where hereafter his lascivious

tactics were to be displayed, nothing more remained for him to

do, than to prepare his victim to suffer martyrdom with the most

discret resignation. It is not to an Elmira that he adresses

himself, it is not a wordly doctrine that he is obliged to paraphrase,

in order to connect it with his secret designs, but it is an

entire new morality which he is obliged to create, and which

he must make her adopt as simple and in common practice. Seduction

borrows a language opposite to that of conversion; seduction

addresses itself to a young soul, naturally so ductile that it

receives every form that the seducer pleases to give. Conversion

on the contrary has a double end to reach; at first it must destroy

adopted and practised principles, in order to substitute those

which are new and opposite. The hypocrite may say:

"Ah! ce n'est pas pécher que pecher en silence"

[57] Because he must avow that the act he proposes to his

victim is a sin, yet it loses much of its weight in consequence

of the secrecy with which it is surrounded

"Le mal n'est jamais que dans 1'éclat qu'on fait.

Le scandale du monde cst ce qoi fait l'offense."

But the seducer in order not to shock the heart he wishes

to enslave, and in order not to alarm that virtue he endeavors

to destroy, must make no mention of the word SIN. The sacrifice

which he covets would not seem perfect in his eyes unless it

were attended with simplicity and nature. The singular novelty

of the doctrine he preaches in impassioned language, cast a doubf

in the mind of a young girl of fifteen, which the bewilderment

of the senses increased; this moment which he has prepared and

which he waits for, is the triumph which is now his own, but

by a kind of subtle perversity he delays to seize upon it, he

enjoys it in silence, he allows it to inflame, to be consumed

and to be extinguished in an infatuating ignorance, in order

to see it reappear with more power and intoxication, and forced

to solicit apparently the entire abnegation of itself. The wretch

has even compelled the victim to solicit the executioner to hasten

the sacrifice. Such was the line of conduct from which Mr. Verren

did not deviate for a single moment.

Already several weeks have elapsed that were to [57/58] bring

to capitulation virtue ignorant of its value, but which as yet

guarded itself by the instinct of it's own preservation; the

hour seemed to have come: to his words, to his language, to his

supplications, to his dramatic arts Verren dared to add the attack;

his immodest hands have seconded his brazen tongue, but if the

soul was shaken and irresolute, if the mind was moved and troubled

in this moment of tumultuous feeling, reason regained it's dominion,

personal dignity revolted against the gross-ness of such profanation,

innocence had not yet succumbed.

However,

If we compromise the decrees of Heaven

our seducer effected a reconciliation with his own senses;

in his disappointment he might say with Dryden:

If Jove and Heav'n my just desires deny,

Hell shall the power of Heav'n and Jove supply.

[Virgil has also said: Flectere si nequeo Superos, Acherontas

movebo.]

He implores her pardon, he humbles himself, but the impostor

fawns only in order to seize again his victim, he violates the

promise of forgetfulness of the past, intended by him only as

a postponement of his purpose, and in the kiss of peace again

inebriates [58/59] himself with voluptuousness, and exclaims

with transport like Heloise:

"Couvre moi des baisers, je réverai le reste!"

[Give all thou canst,--and I will dream the rest.--Pope]

She has not yet quite succumbed; at each conference were new

attacks, but also fresh resistance, resistance, without discouragement,

since the assailant is each time vanquished by the natural exhaustion

of material energy; the danger is pressing, already the dove

no longer trembles under the hand of the sacrificer; no longer

does the sacred sword wear an alarming aspect; she is still ignorant

that like the knife of the Druids it sheds the purest blood of

human victims immolated at the altars of profane men; yet a little

more imprudent confidence and the young maiden will know that

innocence and mystery were never long united. Under these circumstances

it is reported that her brother, her dear brother had arrived,

and that jealous for the honor of his family, he will soon take

under his protection the sister he had quitted with regret.

At this news Verren was alarmed, he feels he must give up

that which he had so much coveted. He must raise the siege even

without the honor of having made a breach; like a timid general

and unskilful diplomatist, he has consumed his time and wasted

his [59/60] forces without having vanquished or seduced his prey;

she escaped his hands stronger by virtue of the power he has

revealed to her, and without benefitting himself; notwithstanding

his perfidy, he is the sport of one who can boast only her ingeniousness.

However, in separating from her he will leave a memento of

their so mystical conferences. Upon the arrival of the brother,

Verren had already discontinued his visits, and when the young

lady left New York for Europe he presented her with a costly

pencil case. A philosophical writer has said that the oaths of

love should be written on sand, and our Reverend hero wishes

the remembrance of his own to be more durable without, however,

their being engraved.

Scripta manent,

Facta probant,

but the simple marks of a pencil are too soon effaced; a suitable

emblem of his passion for the young traveller, who knew no more

of him than as a pale and counterfeit impression of true love,

the traces of which cannot have such a duration as to remind

her hereafter of it's ephemeral existence: like a thought inscribed

on the flying sheet of an album.

This intrigue of the holy man did not cause him to lose, sight

of either his personal security or his interest. His security

admonished him to retire before [60/61] the consummation of his

victory, and his interest, if credit be given to him in his confidential

communications, he accounted for the amount paid for the famous

pencil-case, as being one of the thousand occasions he had of

doing good and relieving misfortune.

CHAPTER VI.

Un écrit anonyme n'est pas d'un honnête home;

Quand j'attaque quelqu'un, je le dois, je me nomme.

The visit of the Prince de Joinville to New York worked up

as we well remember the self-love of many individuals. Every

one wished to be French, and the French themselves did not understand

each other, one wished this; another wished that. The rich importer

forgetting that he lived in a free country, tried to substitute

the aristocracy of money for that of birth or true merit. Those

who were disposed to pay a large sum for admission thought that

they alone [62/63] should approach the prince; but there was

no pit nor gallery, the boxes held all. Such was the intention

of these matadors in asking for a distinction, which, however,

they are very far from practicing in their mercantile logic,

since though they place in the same line the costly tissue of

Thibet, the modest print of Mulhouse, and the durable stuff of

Jouy, they do not offer them at the same price. The mechanic,

on the other hand, in his simplicity, seriously believing in

the principles of equality, which in France he had been persuaded

reigned absolute here, demanded a public entertainment, where

he might see close to him one of the sons of him who in 1830,

we very well remember, shook hands with the workmen of Paris,

and drank with them from the canteen at the bar of the corner.

Those who were judicious wondered at so extraordinary an infatuation

towards a young man who had not yet made his first essay in arms,

and who was known only by "the gentleman his father,"

as was wittily said by a very simple man.

As for the gentlemen of the press, they wondered at nothing,

but laughed at all sides, expecting in this, as in all cases,

a good dinner; for on these occasions they are always or almost

always invited whether French or not, because the Amphitrions

when they have good manners and tact, like to se e the good taste,

order, intelligence and liberality which signalized the festive

occasion publicly noticed.

The dignified, were the only persons who seriously thought

of the proper way to receive a son of France, of being remarked

by him and in advancing their fortune to serve their ambition.

The latter were in our opinion alone justifiable, since a visit

from the king's heir in an ultramarine state, is as good fortune

to the public functionary resident there and distant from the

official mutations which occur at his court, as is a rise on

silk or cotton to the importer or a change of dress or furniture

to the tradesman.

At last, however, gentle reader, of all the projects which

had been proposed by the intelligent gentlemen who are the officious

disposers of public rejoicings, at New York, one was finally

chosen, which it was reasonable to suppose would give to the

Prince de Joinville a cordial and flattering reception. Upon

the Consul General of [64/65] France devolved the arduous task

of drawing up the lists of invitation and designating the guests,

a painful task indeed, almost one of the thirteenth labors of

Hercules. Everyone wished to approach the sun, all wished to

be planets, few consented to be satellites, no one wished to

remain a star; they were like the American army, which consists

of all officers. All hearts were overjoyed, their satisfaction

knew no bounds and seemed to mount the third heaven; some say

that there were some who lost their wits, so great was the rage

for appearing at the grand festival. Oh! Mr. de la Forest had

a most difficult task to perform. Did he well? He did his best

and no one complained; the best and shortest eulogium which can

be passed upon his conduct in this trying occasion.

We may be mistaken in this, but mean that no one complained

openly, or with reason. To Mr. Verren was it left to create a

schism. The why and wherefore is too curious not to be given

in detail. Trifles require time to acquire importance: witness

the balloons!

Although the fact of his being a pastor of a French congregation

would not have assured him a seat at the feast in honor of the

prince, Mr. Verren would have moved all New York to obtain [65/66]

one. He! miss an opportunity of showing himself in public, He!

who for want of the theatre had chosen the pulpit to say: "Look

ye crowd it is I who speak." He! say we, to remember on

that occasion that modesty is a sacerdotal virtue, no! to suppose

this, would be to suppose him capable of an effort towards excellence.

The Consul General then sent him a letter of invitation.

Socrates was accused of hypocrisy and was told that the index

of all vices was marked on his countenance. The sage answered:

"it is true, but I knew myself very early, and had the courage

to subdue my evil propensities."

If physiology was known to the ancients, we have besides phrenology,

of which they were ignorant, and these two sciences united have

enabled us to discover on the head of Mr. Verren, baseness, cupidity,

artifice, dissimulation and pride. But you cannot find on it

goodness, veneration, approbation or self-esteem. Those narrow

temples, that contracted forehead so retreating, that sharp and

almost pointed top leave no place for virtues which distinguish