"IT was when I was at Malu (N. Malaita) that I first came into contact with what I was to know too frequently later on. I visited an island, Basikana, and I heard that a woman lay in the bush, who had given birth to a child. No birth was ever allowed to take place in a village. The mother must go into the bush and there she must remain for forty days. In this case the child died and no one dared go near. Even food and fire from the village were tapu (forbidden): it must be got in the bush. The husband must not go near but he could pay women to help his wife.

["] In this case the husband had hired no one: so, when Peter told me, we set off with food and tinned milk to find the woman. But we found she had swum cross to the mainland where she was no longer tapu, and could get food and shelter till the forty days were over. I told the Basikana folk what I thought of them in plain language.

"They, however, were not angry with me, they just pitied me for not understanding why they could not help the mother."

"I frequently came across such cases. In one of these at Nore Fou the mother died in the bush and the baby was left alone living. Both were tapu. Two Christian men hearing about it, went out and found the baby dead and buried the mother. Their act became known to a brother, Kailafa, a bully and a fighting man. Next day he came fuming to me and declared. 'These men must be killed.' 'Why'? I asked, 'for doing a deed of mercy?' 'No', he replied, 'because they passed me [3/4] on the track while they were polluted by their breach of tapu. I and all Fera-si-bo will suffer if atonement is not made.' 'How do you know you will suffer?' I asked. 'Of course we shall suffer if the spirits are not appeased.' After this he calmed down somewhat and agreed to wait to see if any trouble came.

["] Soon after Fera-si-boa had quite a good time, plenty of fish were caught, no fighting and no deaths. This so impressed the people with the idea that anyhow Christians were exempt from tapu and the spirits powerless against them, that about month later I got a message from Kailafa that a woman had just died on the other side of his islet. If George and Simon liked to go and bury here they might for "I see that it is not a bad thing after all, but quite good."

"So ingrained is the custom that when the time came for the teacher's wife to have her baby, her husband hit upon an ingenious plan to satisfy her scruples. His hut was against the village palisade. He made a hole in the palisade and built an extra room on outside the village! So she was well cared for. They later reduced the forty days seclusion to a week, and, as no harm resulted, the tapu, at least for Christians, began to go a natural way to destruction.

"We have been having a mild epidemic of obstetric cases in the last few weeks of this year. The practice of obstetrics amongst the natives themselves is primitive in the extreme. In the heathen villages, the woman, when she is about to be delivered, is taken to a tiny hovel way from the village. Food is left with her, and there she has her baby, if all goes well. There also, she is left alone to recover from her ordeal, or to die, as the case may be. There is, of course, no way of determining the mortality, but, from my knowledge of the maternal mortality in the more civilized villages, I am persuaded it is high. I have found pathetic cases of neglect in villages quite [4/5] close to the Hospital. One of our Sisters here has worked in the New Hebrides. There retained placenta is as common as it is here, and the treatment is heroic. A coconut is secured to the cord and the woman, with her feet on the coconut, pulls the cord. The modern view is that this is bad practice, coconut or no coconut. In general, however, the natives are beginning to see that the white man's practice of medicine has something to offer them in obstetrics. Just a few hours go, as I write this, a woman had her baby in our obstetric ward. She came from a village about one hundred miles away. She had trouble in her last two confinements, and lost her babies. Her husband is to come for her in a few week's time, and they will paddle back all that way by canoe. Another woman, in hospital at present, has come from an island fifty miles away, having lost her previous babies in difficult deliveries -- both breaches. It is not merely the loss of life that is to be considered -- infants have a precarious hold on life here in any case. It is the needless suffering of these women that seems to be all wrong."

An estimate showed that out of every ten babies born no less than four died.

From a hospital report: "A three-year old, weighed twenty points on admission. She had a large ulcer on one foot and two toes were missing. Another toe was amputated and the ulcer healed." "Hilda, born in the hospital weighed four pounds. . . . Mary, eighteen months, weighed fourteen pounds on admission."

The problems that confront us. How are the numerous uneducated girls in villages, inaccessible to us, to be taught, and, in these same villages how are dirt, disease and superstition to be dealt with?

Surely the only sensible and practical thing is to send native nurses and teachers to these villages, where, as [5/6] Christian workers, their power for good would be immense.

To do this we must have schools where intelligent girls can receive training, and, for those with the vocation, the full course of General Nursing and Mothercraft must be made possible.

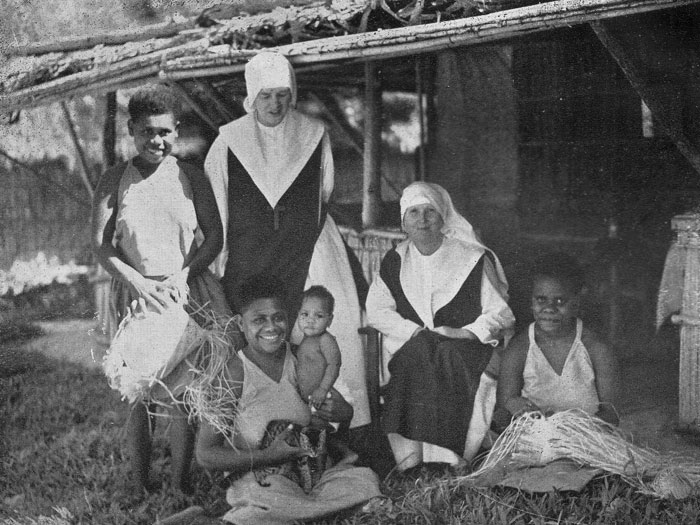

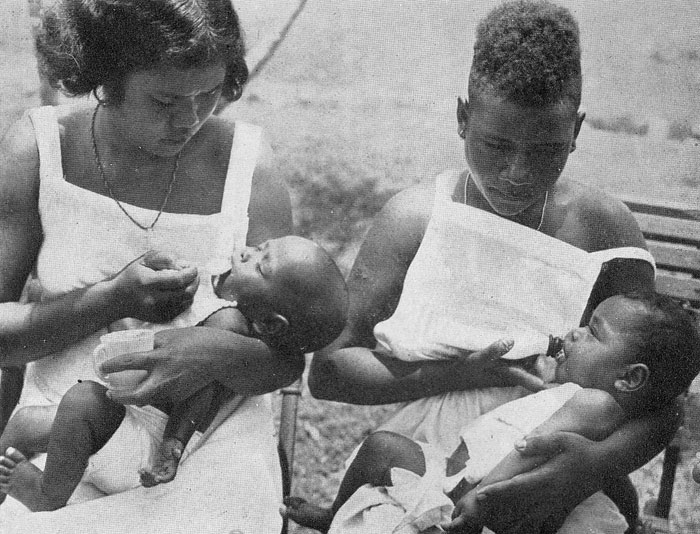

Efforts to solve the problem. In 1940, a specially trained Mothercraft worker was able to establish a first training school at Siota (Solomon Islands). At the end of the first term she wrote, "Twenty-two girls were in residence. When the school reopens after the holidays a number of girls are waiting to come in. We have been fortunate in always having a mother and a baby. Our ambition is to help mother and baby, and so we have made the most of the patients we have had. Our babies are a great contrast to those we see as out-patients or in the villages and the girls are justly proud of them. A village teacher who called the other day said he would like to buy some of them!"

"Apart from milk (imported tins) and cod-liver oil their diet consists of native food which we have grown ourselves. Sweet potatoes, panna and yam are all as nice as English potatoes. (Not everyone person would agree with the word 'nice' here -- Ed.). Bananas cooked or eaten ripe are very easy to digest. Green pawpaw cooked is not unlike vegetable marrow. It is a useful thing to start a baby on. Edible hibiscus, which is nearly like spinach, or kumara sweet-potato-tops are the best 'greens'. We get fresh fruit juice from oranges and ripe pawpaw, and, if these are not available, the milk of the green coconut. Grated coconut when squeezed gives out a cream which is very nourishing and good to mix with food.

"We hope to plant a still greater variety of things including sugar-cane.

[7] "School work takes up a lot of time. Religious instruction, reading, writing, sewing, simple English and singing are taken by one teacher. I have all the Mothercraft and Hygiene. The hardest things to inculcate are obedience and punctuality, but these come with training.

"We have been helped through difficult times. The old enemy, the devil, has tried to lead some astray and failed. We end our term with great thankfulness for all that has been accomplished."

Interruptions. Early in 1942 the Japanese attacked the Solomons and it became imperative to move the missionaries and girls to safer quarters. The Mothercraft centre was transported to Malaita where temporary quarters were found in the General Hospital at Fauabu. Here, there was a new and unexpected development. The Hospital was filled to overflowing and great crowds came as out-patients. What had been awaited for years was accomplished all in a day as far as the girls were concerned. There was so much excitement that the girls had settled in and become regular hospital nurses before anyone had noticed them, by which time criticism was useless. What a boon they were. They looked after the women and children and did all the maternity work. A message written at the time reads "The girls are happy, we are all safe and well."

N.B. The long standing-native prejudice against the use of native women as nurses, but for this occasion, might have continued for a much longer time.

Later on, this Hospital was evacuated as the Japanese landed in the neighbourhood. The white nurses retired into the bush with as many of their flock as possible. There they carried on their work.

"Each day we hoped for the arrival of the Americans, instead of which a boy came up to say that the enemy [7/8] were at the Hospital. The village people decided to go further into the bush and we packed up and moved with them to a distant hill village. The Chief was most kind and helpful and after two days, because of rumours, it was decided that we should go and live in a still safer place. Under a banyan tree in a place chosen by the Chief, a bamboo hut was built and there we stayed for three weeks. It rained most of the time. As soon as it was dark we were serenaded by the frogs. They sounded like little yapping dogs. Then we heard that American troops had arrived but it was still considered unsafe for us to go back to the beach and the Bishop sent me to Tantalau."

Tantalau is a big village. The young men's house was prepared for my use, and another, when a partition had been put up, made an excellent house for the girls and dispensary. A new house was built for maternity work, and in a very short time we were working happily. It was amazing how supplies and equipment turned up. It had travelled miles by devious routes. A very cheering thing was the way the older women were anxious to benefit from Mothercraft training, and came to have their babies and to be looked after by us. I found a man who could speak good English and together we started a class for all the women and girls. My English combination of Scripture, Hygiene and Mothercraft was translated into their own language by Nelson. The men, for their part, became really keen. Little cots were made for the babies and the houses improved as required. I felt very happy about the girls and hoped to carry on until the school proper could be reopened. I was greatly disappointed when I, with all other white women, was ordered to leave the Islands.

N.B. The situation in the Solomons was so uncertain the "High Command" ordered all women out. They went under protest.

[9] Back again at Gwaigio. "The natives hereabouts, knowing that I wanted to start a school again, offered a suitable site here. With the help of the District Officer all arrangements were made about the land and the start became possible."

This time work-boys were employed. Small temporary houses were rapidly built, one to house the white worker and the other for four native girls. Life in such confined space is of necessity of the very simplest. Each day is a picnic but work goes on apace.

Since then Nurseries, Maternity wards, schoolrooms, dormitories, and a Chapel have been built and the centre fully established.

A note says, "We kept the Mothers' Union Festival this year and were able to have a Celebration in our own Chapel. The priest was Samuel Sasai, the native priest in charge of this district. The Chapel was full and the overflow knelt outside on the grass. Afterwards more women arrived and everyone had breakfast on the grass. Later on, the last new building was blessed. It is a native house with bedrooms, kitchen, bathroom all portioned off with leaf walls. Those who had not seen the School were shown round. All were interested in our books and apparatus. Babies, diets and ailments were all discussed. Then back to the Chapel for three Baptisms."

Again and again we are reminded of the good will of the people and their appreciation of what we are trying to do. They have done so much in giving us material for building without any request for payment.

The girls are tremendously keen, it is a pleasure to teach such eager pupils. It is gratifying to see mothers coming back regularly for a check up and advice and not as is usual waiting till the babies are seriously ill.

Results? "I paid a visit to Gwauru where a former school girl lives with her husband and two children, the [9/10] youngest a baby a few days old. I was amazed at the work they had done. Manasseh, mission-trained, once an orderly at the Hospital, has a very neat dispensary where all the minor ailments of the village are treated. Margaret has taken the Mothercraft teaching seriously and has transformed the village. Most of the houses are new and well built, each with a veranda, on which the baby sleeps in a cot. The babes of the village look beautiful and so clean and content, showing the results of right and regular feeding. The parents are happy, going off to work in the gardens with the knowledge that the babies are safe."