"Around each pure domestic shrine

Bright flowers of Eden bloom and twine,

Our hearths are altars all."--Christian Year.

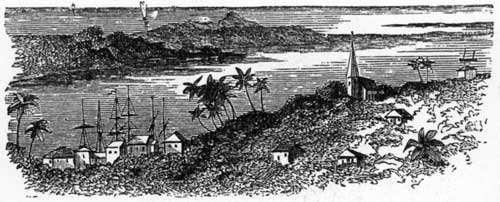

To return to Nassau once more. The flag on the little fort behind the Bishop's house is signalling the arrival of a vessel outside the bar, and before long the "Message of Peace," with the banner of the cross flying at her peak, comes speeding up the harbour, until the trim little schooner drops anchor once more at her moorings opposite the Government offices and public wharf of the little tropical city. The Bishop has returned from a tedious, exhausting tour of some weeks amidst the far southerly islands of his diocese, and is glad to find himself at home again.

His house at Nassau, hallowed as it is by ten years of his occupancy of it, has an interest of its own deserving more than a passing notice; besides that, the liberality of friends in the Colony and in England has been the means of securing Bishop Venables' West Indian residence for all future occupiers of the See, and admirably is it adapted for such a purpose.

[58] Lying back and away somewhat from the bustle of the traders' quarters, the house stands on an eminence, overlooking the town, and is approached through pleasant sloping grounds dotted with orange-trees, and ending in a terrace above, where a flight of steps leads onto the grassy platform on which the Bishop's abode stands, commanding a beautiful view to the northward of town, harbour, and sea. The house, like so many in the West Indies, is a long, straggling, irregular building of wood and stone, with shingle roof, the main body of the dwelling consisting of a long many-doored and windowed drawing-room, with its verandahed gallery running all round it, and attached at each corner to low square turrets of stone, in which are the bedrooms, and in the basement of one of which the Bishop had formed his little private chapel. An excavation in the rock underneath the house, made a cool and pleasant dining-room in the great summer heats. The kitchens occupy a separate block of buildings at the side. At the rear of the house lie the gardens and the Bishop's study. Beyond still, and on higher ground, the fort.

Such was Bishop Venables' home. Here five of his children were born, and here three of them died. Here also it was that the Bishop displayed, when at Nassau, a constant and unvarying hospitality. Indeed, the house was seldom without guests of one kind or another. Missionaries and their families en route from England to some distant part of the diocese, clergy on visit to Nassau on business, or at synod time, or some broken-down [58/61] missionary on sick leave from his out-island parish, made the house their home as long as they were pleased to stay; while the inhabitants of Nassau generally, with visitors from America, Officers of the Army and Navy, and others, found the Bishop's hospitable doors always open to receive them, with a cheery and courteous welcome from their kindly host.

In the "hurricane" months, and during the greater festivals of the Church, the Bishop would be usually in Nassau. But the intervals thus spent at home were by no means unoccupied. A pile of correspondence had to be got through and answered, meetings of all kinds and calls of business filled up the time.

Various objects in the city and its parishes claimed when at home the Bishop's care and attention. Under his auspices a work had been commenced by a devoted Englishwoman, Miss Louisa Fletcher, among the black women of Nassau, the progress of which the Bishop watched with anxious interest. The Bahama Churchman's Union was founded by him for the youths of the city. The subject of education, too, was pursued as keenly as in the old Oxford days; and soon after his arrival the Bishop set on foot a grammar-school for the sons of the merchants and others, which, under a succession of admirable head-masters, still continues to flourish. When "on shore," too, the Bishop preached every Sunday at one or other of the churches in Nassau, and the Sunday sermon was not achieved without cost.

Speaking on the occasion of the Bishop's death, the Rev. [61/62] C. C. Wakefield observes: "Our dear Bishop was never unemployed. He never gave way to idleness himself, nor would he permit it in those over whom he had control. The recitation of the daily offices he would never allow himself to omit, even when pressed for time, or inconveniently situated. He used to say that a slothful man was seldom a very moral one. Thus he would force himself to preach even when physically unfit for the duty, and few know the prayer, study, and concentrated thought which, especially during the later period of his life, were necessitated by a single sermon. Though naturally fluent, he could never address even the humblest congregation without diligent preparation, and those who heard him were soon convinced that his language was not the eloquence of the moment, but the result of careful study of the Holy Scriptures, the writings of the Fathers, and other sacred literature. The tables and floor round the arm-chair in his study were covered with open books of reference, and on no single occasion do I remember to have entered his presence and to have found him unemployed."

"Not slothful in business, fervent in spirit, serving the Lord!"--the words naturally recur in thinking of Addington Venables' fervent, tireless life. Hoc ago--"This one thing I do"--was his constant watchword to himself and to others, and in the strength of which he used to renew himself to ever fresh exertions, often beyond his physical powers. Another favourite text with him was, "I must work the works of Him that sent me," &c.

[63] In the way of relaxation the Bishop had always a constant source of healthful and agreeable diversion in the garden and grounds surrounding his house, which, in all things living for others, he endeavoured to render a pleasant retreat and means of entertainment for friends and neighbours.

There were about the place, at one time, three native Africans as gardeners, "July," "Cambridge," and Hannah, and with these sable gentry the Bishop did great things. Rocks were levelled, lawns made, trees planted, beds laid out, plots of vegetables sown, the Bishop working away as vigorously as any. "You should see Addington digging away at his potatoes!" writes his wife in 1867. His delight in the sights and sounds of the natural world, and his love of animals and all God's creatures, was remarkable; the bird tribe, in particular, had a special charm for him, and the sight of the little winged visitants, as they lighted near him, or made their nests about the house, drew from him an oft-repeated quotation, "Ubi aves ibi angeli." But keenly as he enjoyed, and much as he needed, the retirement of his home when in Nassau, the Bishop by no means shut himself up in his retreat. Society had its claims upon him, to which he never failed to respond, and his genial presence was rarely wanting at friendly or official gatherings in the town, or joining the Saturday "Maroon" party of the West India Regiment, or embarked upon some picnic or fishing or boating expedition devised for the amusement of his own clergy. He was also a warm [63/64] supporter of the St. George's (Civilian) Boat Club, and being a light-weight, used to steer and "coach" the crew at their evening practices in the harbour of Nassau, the only instance, it is believed, on record of a bishop acting as coxswain.

Towards the close of 1873 a pleasant incident occurred to break the routine of the Bishop's labours in the Conference of West Indian Bishops, convened in the month of November, at Georgetown, Demerara. The Bishop sailed from Nassau the second week in October, via Havana, and arrived at his destination towards the end of the month. The gathering was an important one. Of the seven West India sees five were represented, by Bishops Austin, Mitchinson, Jackson, Parry, and the Bishop of Nassau.

This assemblage, the first of its kind, was due in part to the progressive disendowment of the West Indian Churches, and still further to a Letter from the Primate in 1872 to the Bishop of Guiana as senior Prelate, urging an early conclave of the Fathers of the Church at some central point with the view of modifying the evils of disendowment by the speedy formation of Synodical bodies and Sustentation Funds in the various dioceses.

The proposal of the Archbishop was extremely well-timed, and was welcomed by the Bishop of Guiana, who wrote to the Bishop of Nassau inviting him to the conference. "I have just acknowledged the Archbishop's letter expressing my own thankfulness for his sympathy with the West Indian branch of the Church [64/65] of Christ, and my belief that my brethren will experience the same feeling when they peruse his letter. I expressed a hope in my late Charge that the time was not far distant when the Bishops of the respective sees, with Delegates from each diocese, would meet to consider how they may best support each other in the common work they had to do, and the Archbishop's very happy suggestion has quickly followed this expression of my own feelings, long ago entertained by myself and others in this diocese. My idea is, that I might propose Guiana as our place of meeting, and if the proposal be favourably received, I am sure that the whole diocese will join me in offering a welcome to the Bishops, with the clergy and laity who may accompany them; each Bishop, as I trust may be the case, attended by at least one Clergyman and one Layman, as representatives of their respective orders in the several dioceses, and not merely as the nominees of the Bishop. Beyond the charge of the voyage, which will only be moderately increased by coming to us instead of to Barbadoes, no expense will be incurred by our visitors."

The meeting was as cheering as it was novel. The people of Georgetown gave the Right Reverend Fathers a very hearty reception, and entertained them during their stay in princely style. To the Bishop of Nassau the trip was one of delightful novelty. An expedition was made during their visit up the Essequibo to the missionary settlements on its banks, where he saw colonies and schools of native Indian tribes, and was [65/66] introduced to the new and wondrous scenery, and all the strange and gorgeous profusion of the South American tropical forest.

By the end of November the Conference concluded its deliberations; one of its most satisfactory results being the Confederation of the West India dioceses into a separate Province. The bishops were to style themselves as bishops of the West India Church. A Provincial Synod of bishops was to be established, and a synod or church council formed in each diocese, consisting of its bishop, clergy, or lay representatives.

While the conference was sitting, special services and meetings were held, and the gatherings were very numerously attended.

At the meeting of the Guiana Diocesan Church Association, with the Governor, the Hon. E. E. Rushworth, in the chair, the Bishop of Nassau was among the speakers.

"He spoke (says a correspondent of the Guardian of that date) like a man who had been battling with difficulties all his life, and seemed upon the whole rather to enjoy his work. His description of the striking difference between his own diocese and that in which he then found himself, was a piece of quiet humour that told throughout the room. And the account which he gave of the food his clergy had to live upon, the churches in which they had to minister, and the houses in which some of them dwelt, enlisted the sympathy of all; and he spoke to feeling hearts when he described his diocese, in no discontented tone, as the poorest in [66/67] Christendom." He concluded his speech as follows:--"The Church in my diocese has now been disendowed for three years, but we cannot get the people to believe it; for our simple islanders still suppose that the clergyman has a money-box concealed somewhere, and that as soon as it is empty the Queen of England fills it again. In your own rich diocese of Guiana, you need not, I believe, dread disendowment, however severely its effects are felt in the poorer sees; though even there I do not believe that our Lord will suffer His Church to fail. We might have fewer clergy, but their ministrations would be more blessed. We might have fewer celebrations of Holy Communion, but a larger measure of God's grace at the few. If the Church fail, it will not be because she is disendowed, but because her members are worldly and selfish, and unwilling to make sacrifices for the spread of the truth."

At the closing service, on the eve of the dispersing of the Conference, the collection of $194 was handed to Bishop Venables for his needy diocese.

The Bishop's own accounts of the journey to the Conference and his return, stuck in as they are both of them at the end of a letter of business, are brief and characteristic. He starts in a hurricane and returns with a ship-wreck, both of which, however, are dismissed after his fashion, with very slight notice as follows:--

"H.B.M. Consulate, Havana, October 12, 1873.--I am on my way to Demerara to the meeting of West Indian Bishops. The evening after we left Nassau we ran into [67/68] the edge of a hurricane, which knocked us about a little, so we prudently turned tail, and ran back forty miles."

Here is the return in December:--

"I am just back (Nassau) from Demerara, where we had a most harmonious meeting, and got wrecked on my way home, but under no circumstances of danger whatever."

As a sequel to the part taken in the Conference by Bishop Venables, may perhaps be fitly inserted in this place an extract from a letter addressed to Mrs. Venables by one of his former clergy, the Rev. H. Humphries, now working at Berbice, in British Guiana.

"The Bishop's visit to Demerara seems to have produced a profound impression. Many persons in George Town spoke to me about him, and the Bishop of Guiana, Dr. Austin, told me that no man in so short a time had produced such an impression or made so many friends. His extempore preaching, which is quite a novelty here, was very much appreciated and liked; and the rector of St. Philip's told me with pleasure of the Bishop's coming a long distance--two and a half miles--to the daily celebration at his church, and of his strikingly reverent manner in celebrating the Holy Eucharist.

"His address to the large assembly of children at the same church on the last day, and his speech at the missionary meeting, are often spoken of as peculiarly felicitous. And lastly, a gentleman who travelled with the Bishop down the islands, mentioned with great pleasure his staying on board whilst others went on shore, in order to preach to the sailors and others, and in doing so engaging [68/69] their attention by his familiarity with nautical language, and not least by his own earnest and affectionate manner.

"I can assure you that I shall always look back with fondest pleasure to those years I spent in this diocese, for from the first moment to the last I always received the greatest kindness, sympathy, and consideration both from his Lordship and from yourself, and I feel thankful to have been allowed the privilege of working with him for the Church. I was so glad to have been with him in America"--his last illness.--"His patience and humility during that time of suffering were so great that I can never forget them; nor, during his lifetime, his gentleness with every one, and his self-denial and perseverance in Church-work at all times, and often when weakness suggested rest. How often, I cannot tell you, it encouraged me to work more earnestly, and doubtless helped others to do the same!"

Meanwhile the year just ending had not been without its trials, and death had removed two of the Bishop's most cherished helpers, the Rev. Albert Rivers and the Rev. W. Hildyard. Mr. Rivers, to the great grief of his people, had been obliged to resign his post of usefulness at Grand Turk, and had gone back to England hopelessly invalided, and in the spring of 1873 his gentle, peaceful spirit passed away. "I have to thank God" (the Bishop wrote while still unaware of his loss) "for several good and earnest men, who from time to time have responded to my call, but to few do I owe such a debt as to Albert Rivers!"

[70] William Hildyard's death in the summer of the same year was even a more terrible loss. He had been struck with fever, brought on by exposure while on missionary travel, and his unwillingness to give way to the malady, amounting quite to a recklessness of his own life, only aggravated the complaint. At last, while preaching at a distant station, he completely failed, and was carried home that night by a vessel to his own house. The Bishop, in a letter to the Rev. R. M. Benson, tells the melancholy sequel.

"At first nothing serious was anticipated, but after a few days his mind became affected with strange fancies, and strong doses of morphia failed to produce sleep. It was not, however, until the Wednesday week after his return home that I received intelligence of his state. I immediately fetched him away, and by Friday night had him in my house. All efforts of the doctors were powerless to arrest the disease, although almost to the last I had good hopes of his recovery, and about a week after his arrival in Nassau he fell asleep in the room you occupied. On the previous day he received Absolution from me, and a few hours before his departure the Holy Sacrament was administered to him. Dear Benson, the tears nearly force themselves into my eyes as I write, although it is a fortnight since his death. May God turn it to our good! I hardly know whom the loss of my dear friend will affect the most--myself, the clergy, or his parishioners. As regards myself, the blow is a very heavy one; it has [70/71] removed my own counsellor and confidential friend. In my troubles my wile used to encourage me by reminding me that I had Hildyard to depend upon. The high respect in which he was held enabled him to give me a moral support which no other can give. . . . Then, as regards the clergy, his loss is incalculable. The leavening influence of his character and holy life must have raised the clerical standard amongst us. I feel it so hard to keep myself up, and of course so far more difficult to elevate the tone of my clergy, that I miss him most painfully. And then the poor parish! It was the first disendowed parish, and Hildyard took it when I did not see my way to provide an incumbent for it, and during the three years he was in charge of it built two churches, completed a third, began a fourth, and worked it as it had never been worked before."

Again, on being asked for a sketch of Mr. Hildyard's life, the Bishop wrote (in doing so unconsciously reflecting many points in his own character): "I fear that it will be difficult to produce an interesting sketch of Hildyard's career, at least which would interest those who were not acquainted with him. There were no striking incidents in his life and work. Though of a most refined and cultivated mind, there was nothing brilliant about him. The one thing remarkable in him was his quiet goodness and simplicity. You felt when with him that you were in the presence of a good man. He gave me the impression, more than any one I have ever known (except Mr. Pinder of Wells), of being one [71/72] whose life was 'hid with Christ in God.' He seemed to be ever conscious of God's Presence. As I write these words I am reminded how that I have heard him, when with me on visitation, twice preach on God's Presence--a favourite subject with him, I should imagine. Indeed, so absorbed did he appear to be in spiritual things, that although no Puritan, it seemed an effort to talk on worldly matters. His work was the one point of interest, and I believe that his devotion to it led him sometimes to be careless about necessary food. Literally, his 'meat' was 'to do the will of Him,' &c. It was most gratifying to me to learn after his death that, although his work was so very trying, physically and mentally, the two or three years that he spent in the diocese were the happiest of his life, and that he intended to make it the field of his ministry for life. I ought not to omit to mention his guileless simplicity, which led him to believe the best of every one, and which I am afraid was often imposed upon; nor his religious care for the poor, of which advantage was frequently taken. If these were weaknesses, they were certainly amiable ones. But you will see that such a character will scarcely bear 'dressing up' for missionary periodicals!"

A year and more after Hildyard's departure, the Bishop revisited his former parish. "I found his memory still affectionately cherished, and should hope there are many on whom he has left his mark for good. A very intelligent-looking coloured man said to [72/73] me, 'Mr. Hildyard did more for me than any one else!' And the man had in former days led a very evil life; but Hildyard had been very hopeful of him, and was so convinced of his penitence as to ask me to license him as a catechist, and I refused. Yet I found this man the other day the mainstay of a young mission which Hildyard had started, and I was so much struck by his altered tone and demeanour, that, upon receiving from his clergyman a favourable account of his consistent life, I gave the license for which Hildyard had asked in vain. The missionary in charge promises to superintend his reading, and before many years I may see him perhaps ministering in holy orders. If this should ever be" (adds the Bishop), "Hildyard's brief ministry will not have been in vain!"