|

|

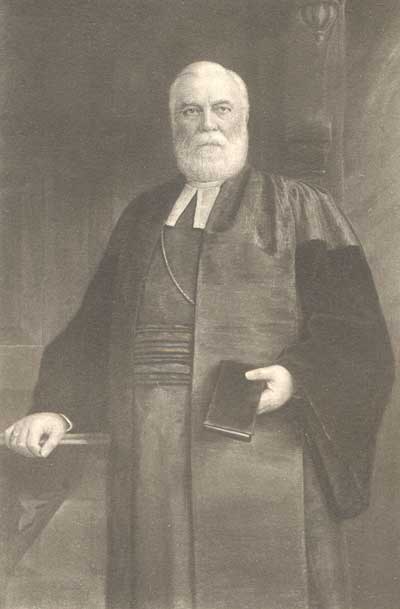

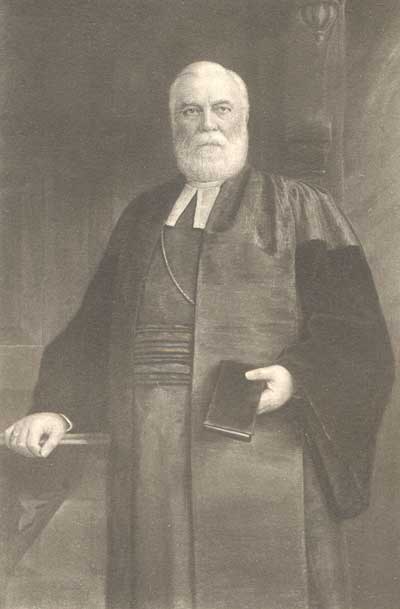

At a stated meeting of the NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY, held in its Hall, on Tuesday evening, December 2, 1902, the Rev. WILLIAM R. HUNTINGTON, D.D., read An Address Commemorative of the Very Rev. EUGENE AUGUSTUS HOFFMAN, D.D., late President of the Society.

On its conclusion, Mr. George R. Schieffelin offered the following resolution, which was unanimously adopted:

Resolved, That the thanks of the Society be presented to the Rev. Dr. HUNTINGTON for his eloquent and appropriate commemorative address delivered this evening, and that a copy be requested for publication.

Extract from the minutes.

SYDNEY H. CARNEY, JR.,

Recording Secretary.

THE late Eugene Augustus Hoffman, Doctor in Divinity, Doctor of Laws, had been, at the time of his death, for ten years a member of this Society, during one half of which period he had served it as Foreign Corresponding Secretary. In February, 1901, Dr. Hoffman was chosen President of the Society, being the nineteenth in the succession of eminent men upon whom that honor has been conferred. He had been an officer only a little more than a twelvemonth, however, when death overtook him, and, in his seventy-fourth year, he fell on sleep.

Our annals would be incomplete were they to contain only the bare record of these facts. The Society owes it to itself and to the man who was both its regent and its benefactor, to write beneath the letters of his name and the dates of his birth and death, some estimate of his character and at least an outline sketch of his career. To me, less well equipped for so responsible a [9/10] task than could be wished, the duty has been assigned of putting this deserved tribute into form.

Eugene Augustus Hoffman, among other claims upon the attention of a Society bearing the name which ours does, had noticeably this one, that with the history of New York his family had been identified for generations. Martinus Hoffman, a Swedish officer of horse, settled in New Amsterdam soon after the middle of the seventeenth century, and from him our late associate traced his descent. Even under a democracy, some value continues to attach itself to heredity, and to bear a name which a community has become accustomed, by long use, to hold in honor, is always, to a young man, just so much starting capital. It enables him to take at a bound those lower rungs on the ladder of success which the less highly privileged must laboriously climb. Hoffman enjoyed this initial advantage of good birth; he had not to struggle for recognition; his forebears had secured that for him in advance. Moreover, there was, in his case, no handicap of slender means. He had riches in possession, riches that had come to him without his seeking, and this also was so much to the good. Solomon, to be sure, puts riches into [10/11] Wisdom's left hand rather than her right, but that is only to suggest that she must be more than ordinarily careful in the use of them; the sword-arm must be left free.

The curse of a city's life is not that its young men are rich, but rather that so few of its rich youths wake up to the consciousness of trusteeship. Gold in the hand does no harm, provided there be, at the same time, iron in the blood. In too many instances, perhaps in most, an inherited fortune makes either for pleasure-seeking or penuriousness. To discern in wealth a divinely fashioned and providentially bestowed instrument for the carrying out of a definite purpose, and that purpose a lofty one, is given to comparatively few.

Hoffman had, to the end of his days, a sportsman's instincts. He was fond of the woods and streams, and thoroughly at home with rod and gun. He enjoyed travel. He might have devoted a lifetime to the hunting of big game in Asia, Africa, and America, and nobody would have blamed him. People would have said,

He has done what a gentleman of his tastes and aptitudes might have been expected to do. "Every man to his fancy." When he died he would have been missed at the club for a few weeks, and that would have been the end of it.

[12] Hoffman had also the taste of a collector. He enjoyed the bringing together into one place of rare and curious objects. It was a pleasure to him, late on in life, to know that he had possessed himself of the most complete library of Latin Bibles in existence. A collection of rare insects fell under his eye. It was not precisely in his department, but because it had been long in the gathering and was presumably full, it attracted him. He bought it, and gave it to the Natural History Society. In the gratification of this taste for collecting, Hoffman might also easily have spent a fortune. He might have been a gatherer of books, of pictures, of gems, of porcelains, and nobody would have thought the worse of him, rather, perhaps, the better. Such tastes are blameless in themselves, and the satisfaction of them is generally accounted creditable. As a matter of fact, however, young Hoffman chose to be neither sportsman nor collector. He chose to be a parish priest. After preparatory studies in the Columbia Grammar School of this city, he entered Rutgers College, and passing from thence to Harvard, received at that venerable seat of learning his two degrees in Arts. In 1848 he matriculated at the General Theological Seminary, an institution with which, in after years, his name was destined to become inseparably [12/13] joined, and thence, in due time, was graduated, having already become a candidate for Holy Orders. The pastoral work of Dr. Hoffman as a clergyman of the Episcopal Church was done in four places. He was successively rector of Christ Church, Elizabeth; of St. Mary's, Burlington; of Grace Church, Brooklyn Heights, and of St. Mark's, Philadelphia. In each one of these cures the energy of the man manifested itself in ways that left abiding reminders. Devoutness and diligence went hand in hand; " Not slothful in business, fervent in spirit," seeming to be the chosen motto of his life. Perhaps his most noteworthy achievement, as a pastor, was the founding in Philadelphia of a workingmen's club, said to have been the first of its kind ever organized in this country. Nothing could have better illustrated the clear, practical judgment of the man than this well-considered attempt. I call it an " attempt," for nobody pretends that we have as yet got beyond the experimental stage in our dealings with the question, How can the Church and the wage-earners arrive at a better understanding? The belief has gained currency (we will not stop to ask why or how) that workingmen, or, to speak more accurately, those who labor for a daily wage, have become alienated from the Christian Church. This estrangement [13/14] is by no means confined to Protestant lands, but is observable in every region of Christendom. In Latin countries the feeling finds expression in noisy abuse of the priesthood and in the promoting of so-called "anti-clerical" demonstrations for political ends. In Germany, England and America, the like disaffection shows itself both by a general neglect of the institute of public worship and by frequent denunciation of the world ecclesiastical as being in league with capital and unsympathetic toward labor. A common way of describing the situation is to declare that workingmen are disposed, when opportunity offers, to cheer the Christ and to hiss the Church. In view of the fact that the wages both of skilled and of unskilled labor are higher in Christian countries than elsewhere, and of the further fact that labor demonstrably owes to the Church the most precious of all the franchises ever secured for it, I mean the segregating of the weekly rest-day, the alienation in question is one not easy to explain, though clearly some explanation there must be. It would be hard to suggest a more promising path toward daylight on the subject than the one Rector Hoffman chose. The trouble with preaching is its onesidedness. In a church, the minister may stand up and discourse ever so eloquently on the [14/15] ethics of the Sermon on the Mount, or ever so learnedly on the history of the relations between employers and employed, or ever so philosophically on the theory of social economics, but there is no chance to join issue. The man with the difficulty which has not been met, the question which has not been answered, must stay silent in his place to the end. In the club, on the other hand, every man may say his say, state his point, air his grievance, suggest his cure-all. Of course, there is the danger of patronage, when the club is one that has been organized from above. A certain condescension on the part of the better dressed and the more grammatically cultured may betray itself to the utter spoiling of the whole business, and, unless such baleful influences can be barred out, the club may as well adjourn sine die. If, however, such a club be a genuine thing, and not only affects but effects the habit of give and take, there is no limit to the good that may come of it in the way of a better understanding all round. But this is aside from the purpose; I merely desired to put it on record, as an evidence of Rector Hoffman's sagacity, that he not only diagnosed, earlier than most, a distemper of the body politic which threatened, and still threatens, serious trouble, but also suggested and put [15/16] in practice a method of treatment not destitute of promise, certainly alleviative, possibly curative.

Dr. Hoffman was now exactly fifty years of age, a critical epoch in a clergyman's life, often denominated, half playfully, half tearfully, "the dead-line." That it was really anything but this in his case soon became abundantly evident. A call reached him to assume the deanship of the General Theological Seminary. It was an invitation that had come before, in fact twice before; but this third time it was heeded. In 1879 the move was made from Philadelphia to New York, and a career entered upon, the fruits of which are only just beginning to reveal themselves.

When Dean Hoffman, as we must now call him, took charge of the General Seminary, the fortunes of that institution were at a low ebb indeed. "Poverty-stricken" and "forlorn" are the epithets that most readily suggest themselves to any one who recalls Chelsea Square as it looked in those days. Two gray old buildings, lined up on the southerly side of a half-fenced space, which looked more like a common than a quadrangle, constituted what we nowadays call the plant. Under those two roofs were huddled dormitory, refectory, library and class-rooms. [16/17] It was a beggarly showing indeed, though, as a visible symbol of the general condition of the Seminary from the financial and temporal point of view, eloquent enough. Well might the young theologues going to prayers have taken for their processional that mournful Psalm, Qui regis Israel, "Why hast thou then broken down her hedge that all they that go by pluck off her grapes? The wild boar out of the wood doth root it up and the wild beasts of the field devour it."

The new Dean took in the situation at a glance, and straightway prepared to better it. Choosing, and most wisely, the English type of college architecture as his standard, he proceeded, in accordance with a preconcerted plan, to construct, section by section, the truly magnificent range of buildings which now imparts to Chelsea Square a look of distinction as marked as was, in the former time, its air of desolation.

There were those, at first, who distrusted the wisdom of the plan. "Take the institution out of town," they urged, "and, in the quiet atmosphere of some suburban neighborhood, where land is cheap and all distracting sights and sounds are absent, build up the Seminary of the future." The Dean knew better. Looking out [17/18] from under those shaggy eyebrows, he saw what they could not see. He argued, and argued rightly, that the place of all places in which to train ministers for a country plainly destined to be the seat of an urban rather than of a rural civilization, must be none other than the heart of a great city. To-day nobody thinks that he was mistaken. He gave to the beautiful sanctuary which forms the centre of the Seminary pile the name " Chapel of the Good Shepherd," being probably of the belief that, under modern conditions, the silly sheep are quite as likely to be found straying in city streets as in country lanes. At any rate, here he planted his chapel and his halls, right in the thick of things, slums on the one hand and sky-scrapers on the other, and here those quiet dwelling-places are likely to abide for many a long year to come. With so much on his hands, Dean Hoffman might well have held himself excused from activities elsewhere; but no, while in the midst of his great work at the Seminary, he found time to preside over the construction of one of the most sightly of the many dignified school-buildings which adorn our city, and to score his name deep on the lower courses of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, yes, and upon its lofty arch as well.

Doubtless, had he lived, he would have added [18/19] to these achievements the kindred one of carrying to a finish the accepted design for the building in which this Society hopes, some day, to find itself permanently housed.

But Hoffman was very much more than simply a builder, though to be that, and only that, is no mean credit. Members of an Historical Society have no need to be reminded how closely architecture is linked in with the progress of civilization, and how strongly marked has been the influence of memorable buildings upon the fortunes of races. Who shall declare the tenth part of what the buttressed walls and vaulted roofs and mullioned windows of the ancient city of Oxford have done, not only in a direct way for the thousands of youths who have spent their student-days in contact with such sights, but indirectly for the intellectual and spiritual uplift of the people of a whole realm?

"I passed beside the reverend walls

In which, of old, I wore the gown;

I roved at random through the town,

And saw the tumult of the halls;And heard once more in college fanes,

The storm their high-built organs make,

And thunder-music rolling shake

The prophet blazoned on the panes."[20] Of such sort is the poetry which noble architecture inspires. William of Wykeham may not have been the greatest of divines, but he piled up stones in a way that has proved helpful to divinity studies from his day to ours. Bishop Butler is hardly the witness whom one would expect to see summoned to testify in behalf of builders. We are accustomed to associate him with the abstract rather than with the concrete. And yet we find the author of " The Analogy," in his later days, charging the clergy of Durham to pay due attention to the outward and visible elements of the Church's life if they would not see religion, through over-much vaporizing and volatilizing of its substance, cease to continue a recognized presence on the earth.

But, as I was saying, Dean Hoffman was more than a builder of buildings. It was his constant ambition to raise the standard of scholarship in the institution over which he presided, not only by increasing the number of the teaching staff, but also by making the examinations stiffer and the requirements for admission more exacting. Moreover, he was never so deeply immersed in the local affairs of his Seminary as to lose sight of the larger interests of the kingdom of God. In Africa, in China and in Japan, his name was known because of his watchful [20/21] oversight of missionary enterprise in those lands, while, here at home, there were few who, with a more determined grasp, handled the problem how to keep American civilization Christian. As a Church legislator also he has left a noteworthy record. He was an active member of six General Conventions and member-elect of a seventh.

At more than one of these sessions it was my misfortune to find myself ranged on a side antagonistic to that which he espoused, and, perhaps, for this very reason, my testimony is of the more value when I bear willing and emphatic witness to the patience which he ever manifested in the face of opposition, the modesty with which he bore the honors of victory and the dignified calmness with which he took the disappointments of defeat. In many a warm debate I have been his near neighbor, and I do not remember having ever seen either his courage or his temper fail him. How much this means, all who have had any acquaintance with the ways and doings of deliberative assemblies understand.

For obvious reasons I have dwelt in this paper almost wholly upon the public aspects of Dean Hoffman's memorable career. There was a side of his character which I have scarcely touched--the affectional and the devotional sides. Our [21/22] brother departed was a man of a very warm heart. Those whom he honored with his friendship he loved tenderly. "To poor and needy people, and to all strangers destitute of help," to use the fine phrase of the English Ordinal, he was ever ready to attend. The staunch Anglicanism of his nature may possibly have made him seem, to some, to be over-formal in his conception of worship, but the deep genuineness of his devotion no one questioned. Would that time permitted my quoting at length from the eloquent tribute paid him by his life-long friend, the rector of Trinity Church, an utterance fragrant with the aroma of the old English divines, and worthy of the pen which sketched Hooker and Sanderson and Herbert and Donne.

"Broad in his views and aims," writes Dr. Morgan Dix, summoning up his estimate of Hoffman, "broad in his knowledge of men and things, broad in his estimate of the worth of this world and the value of life, broad in sympathy, in tastes, in the right understanding of affairs, the conception of duty, the skill to deal rightly with other men."

In the course of his official life, Dean Hoffman was the recipient of many academic distinctions. The Universities of Oxford, Columbia, Trinity (Toronto), King's (Nova Scotia) and the University [22/23] of the South, Rutgers, Racine and Trinity College, all admitted him to the Doctor's degree, in one or other of its forms; but better a friend's praise, honestly spoken, than all the honors of all the schools.

[27] AT a special meeting of the Executive Committee of the New York Historical Society, held Thursday, June 19, 1902, the Librarian submitted the following resolutions, which were adopted by a rising vote:

The Executive Committee has learned with deep sorrow of the death on the 17th inst. of the Very Rev. Eugene Augustus Hoffman, D.D., President of the Society. Therefore be it

Resolved, That this Committee will attend the funeral services at Trinity Chapel on Friday afternoon, the 10th June, at three o'clock.

Resolved, That a Committee of Three be appointed to prepare suitable resolutions on the death of Dean Hoffman, to be reported at the next stated meeting of the Society, October 7th proximo.

Resolved, That a friend of the family of the late Dean Hoffman be invited to prepare and present to the Society at some future meeting a memorial of the late President of the Society.

Resolved, That the building of the Society be closed on the day of the funeral.

The Chair appointed Mr. F. Robert Schell, Dr. Sydney H. Carney, Jr., and Mr. Robert H. Kelby a Committee to prepare resolutions, to be presented at the next meeting of the Society, on the death of Dean Hoffman.

Extract from the minutes.

DANIEL PARISH, JR.,

Secretary.

[28] AT a stated meeting of the New York Historical Society, held on Tuesday evening, October 7, 1902, Mr. F. Robert Schell, Dr. Sydney H. Carney, Jr., and Mr. Robert H. Kelby, the Committee appointed to prepare resolutions on the death of Dean Hoffman, reported the following preamble and resolutions, which were adopted by a rising vote:

Since the last regular meeting of the Society it has been called to mourn the loss of its distinguished President; being desirous of expressing on behalf of the Society its appreciation of the generous and kindly disposition of Dean Hoffman, the sincere respect, gratitude and affection with which his name will ever be cherished, your Committee offer the following resolutions:

WHEREAS, The New York Historical Society has received the sad intelligence of the death on June 17, 1902, of the Very Rev. Eugene Augustus Hoffman, D.D., LL.D., D.C.L., President of the Society.

Resolved, That we wish to unite with his kindred and friends in lamenting his decease.

Resolved, That we record with gratitude his great interest in the advancement of the Society's welfare during the years of his membership, ever actively co-operating in furthering the completion of the proposed new building of the Society.

Resolved, That we offer our tribute of high esteem to his memory for his generous gifts to the Society during his lifetime, and are deeply sensible of his lasting interest in our institution as expressed in his latest bequest.

Resolved, That an engrossed copy of these resolutions be transmitted to the family of Dean Hoffman; and be it further

Resolved, That the Society do now adjourn out of respect to the memory of our late President.

Extract from the minutes.

SYDNEY H. CARNEY, JR.,

Recording Secretary.

Project Canterbury