Project Canterbury

The Czecho-Slovaks

By Robert Keating Smith

New York: The Board of Missions, no date.

Transcribed by Wayne Kempton

Archivist and Historiographer of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, 2008

Portrait of John Huss

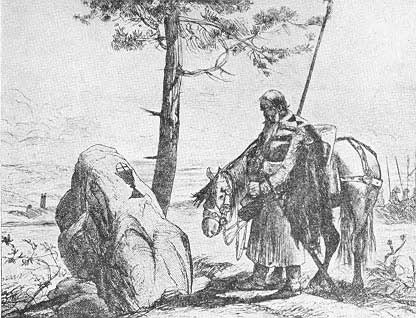

Czech Soldier of the XVth century; Note the chalice on the gravestone and on the shoulder of the cloak.

Czecho-Slovaks and Rumanians celebrating their independence in front of Independence Hall, Philadelphia Pennsylvania

"Sokol" Class in gymnastics, Westfield, Massachusetts.

Choir of Czecho-Slovak boys, Church of the Atonement, Westfield, Massachusetts.

This is the first of a series of pamphlets on the different races in preparation by the Department of Christian Americanization of the Board of Missions. Further information may be secured by addressing the secretary, Reverend Thomas Burgess, Church Missions House, 281 Fourth Avenue, New York, N. Y.

THE CZECHO-SLOVAKS

SUDDENLY, like a flash of lightning, the Czecho-Slovaks stepped into the page of history written by the Great War, and now people are asking, "Who are these people with this strange name?" The truth is that the Bohemians, repudiating their former name and publishing their own racial title, Czech, (pronounced as if spelled Check), have at last been freed from their ancient oppressors, the Hapsburg family, and taking the arm of their weaker racial brethren, the Slovaks of northern Hungary, once more stand before the world an ancient nation reborn.

The name Bohemia has been written large in many a page of history, as for a thousand years these virile people stood bravely out against the tide of pan-Germanism until their country projected alone into Germany almost like an island. The nature of Bohemia itself, a fertile, undulating basin, surrounded by formidable mountains and containing nearly every natural product necessary for civilization, makes it, as Goethe said, "a continent within a continent," and the history of Bohemia, a struggle to maintain an independent nationality by repelling successive invasions; is more like that of an insular country. Indeed, had Bohemia's mountains been England's seas, her history would have been similar. During the last century Bohemia became an industrial state, and grew to be not only the chief manufacturing province of Austria [1/2] but also one of the first manufacturing countries in Europe. Now, Austria, stripped of Bohemia, is not merely bankrupt but rendered almost incapable of independent existence as a state.

The Slavic Czechs entered Bohemia peacefully in the fourth century, after the original Celtic people had been forcibly ejected by the marauding Germanic tribes and the country left with fields and valleys lying fallow. Home-loving and gentle, these people tilled the farmlands and opened mines in the mountainsides. "This branch of the Slav peoples," says Georges Bourdon, the French writer, "installed in Bohemia from the fourth century until the seventeenth, was ahead of the rest, and from that very moment could boast the glory of having created a culture and having indicated to Europe the road to the future. These were the Czechs, pioneers of liberty and soldiers of the truth, who for a long time contended against the convulsions of Germanism, and they contended without flinching. Conquered at last, in 1620, they did not yield, but, bleeding from their wounds, awaited their time,--and it came!"

The Czechs and the English

One of the old, old Christmas carols sung by the children, and again year after year by men and women in the Church of England and the Episcopal Church in America, never losing its popularity, always quaint and lovely, is "Good King Wenceslas." The music is "traditional," that is, it has been sung by the English from time immemorial. But who among us knows that Wenceslas was king of the Czechs in Bohemia as far back as the year 925, when Athelstan was West Saxon king in England, and Dunstan was a boy in Glastonbury [2/3] destined to become Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury? We do not know how long a time it was before the saintly deeds of the Czech king came over in story to England, nor when English children began to sing about him at Christmastide. But the carol stands as a type of the influences which drifted westward century after century from these eager Slavic Christians to their more stolid cousins in England. A still closer alliance between England and Bohemia was formed when, in 1381, Richard II married a sister of a later King Wenceslas.

Conversion to Christianity

The Czechs became Christian long after the British, and even after the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain, but their Christianity came to them so romantically that the tale of it reads like some long-forgotten fiction of old folk-lore. But that the story is true, the witness of an ancient language testifies; for the Old Slavonic used in the Eastern Orthodox Churches still lives in the form that it had when it issued warm on the breath of the first Czech Christians a thousand years ago. Christianity came to the Czechs from the East, from Constantinople, and from Christian Greece. Two young men, consecrated missionaries, came out from Salonica with their learning and their zeal for Christ, and went up the Danube River past many a Slavic tribe and beyond the knowledge of man, until they found the pleasant and fertile valleys of Moravia. These were Cyril and Methodius, ambassadors of Christ to the Czechs. They brought the story of the Cross to these people in their own tongue, and Cyril wrote out the Gospel for them that they might read it for themselves. Because they had no alphabet, Cyril made one for them, and invented [3/4] quaint letters which helped out the Greek alphabet to express Slavic sounds. Today the Cyrillic alphabet is universal in Eastern Europe, and is familiar to most of us in Russian print. This conversion of the Czechs occurred in the year 860.

Greek, not Roman

German missionaries representing the Church of Rome, had, before that, tried to convert the Czechs in Bohemia, but even at that early date Czechs and Germans found themselves inexorably and permanently opposed. So in Bohemia and Moravia were established Greek rather than Roman rites and doctrines. The gift of the Roman mind is law and the duty of submission to authority, while the Greek mind offers to the world the freedom of the human soul; this is true even in the Christian Church. So the gift of the Church of Rome through German missionaries, the Czechs flung back, and turned with joy to spiritual liberty and living faith which the Eastern Church brought them.

John Hus

No wonder that when the Reformation began in England and "The Morning Star of the Reformation," John Wycliffe, preached, another answered him from Bohemia--John Hus, preaching in the Bethlehem Chapel in Prague. It was as though once more the morning stars sang together and the sons of God shouted for joy! John Wycliffe died in peace in his own little parish, but John Hus was reserved for martyrdom. To his own amazement, and to the amazement of both England and Bohemia, John Hus was brought by German intrigue before a council summoned by the Pope at Constance, and that council declared Hus a heretic. Never was there a more infamous council nor a wickeder sentence. John [4/5] Hus was burned at the stake July 6, 1415. The authorities ordered his body burned and his ashes thrown into the river Rhine. Strange to relate, the same council condemned Wycliffe as a heretic (although he had been thirty years dead), and ordered his ashes cast into the river Avon. When the commission appointed to dig up the bones of Wycliffe, came to the little English village of Lutterworth and disturbed the graveyard of Saint Mary's Church, there must have come to the hearts of the plain English folk a bitter desire to be freed from such foreign desecration of their religion.

Revolt--John Ziska

War flamed up in Bohemia, and four great German armies marched upon the Czechs at intervals of two or three years, only to be hurled back utterly defeated by the Czech armies led by Ziska, one of the most picturesque figures in all history. An old man, short and broad, with long, slender nose and a fierce red moustache, blind in one eye, over which he wore a patch, he called himself "John Ziska of the Chalice, commander in the Hope of God." The people were fighting for their religious liberty, for the free reading of the Holy Bible, for the receiving of the chalice by the lay people in the Holy Communion, so that the chalice became their standard, and they wore it embroidered on their banners and tunics. In the year 1436, antedating the Reformation in the Church of England by a century, Christendom accredited to the Czechs a national Church, independent and self-organized, with bishops, priests and deacons, possessing an inherent vitality. The people sang themselves into religious fervor, and transformed the ancient Greek Church custom of singing Easter hymns, [5/6] into singing hymns the year round. Nothing like it had been known before in the world. Little do we think as we sing hymn after hymn in church and at home, whence came this gift to Christendom. The hymn, "Christ the Lord is risen again," is one of the Czech Easter hymns. Not a Roman priest was to be found in Bohemia or Moravia, and only the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 prevented reunion with the Greek Church.

A Church Dispersed

But secretly and constantly, by political intrigue and ecclesiastical trading between Rome and Austria, forces were at work for two centuries to break up the solidarity of Nation and Church. The Jesuits were introduced in 1556, and they entered with orders to burn every Bible and hymnbook and every piece of literature written in the Czech language. Women preserved family Bibles by baking them in loaves of bread, and bishops and priests conducted divine service in the woods and on hill tops. By the year 1620 Germany and the Roman Church had wholly destroyed the nation. The people fled from the land, and wandered over the face of the earth. Millions were killed or starved to death. Many emigrated to England, where in one generation they became Anglicized, changed or translated their names, and in another generation found themselves in Holland and then in New England among the Puritans, and in New York City and Pennsylvania. Fragments of the Episcopal Church of the Czechs, greatly disorganized and much altered by adverse influences, were found here and there. The Moravian Church was one of these, recognized in 1749 by the British parliament as "an ancient Protestant Episcopal Church." The strange [6/7] thing about these people then, as it is now, was their swift acceptance of the English language, and the Moravians preached the Gospel as though they were Englishmen. It was John Bohler of the Moravian Church who started to carry the Gospel to the Negro slaves in South Carolina, met John Wesley, and converted him to the missionary aspect of the Church which led to the great revival of 1737. The last bishop of undoubted apostolic succession, however, was John Komensky (Comenius), the founder of public school education, who died in Holland in 1670. Such was the end of a glorious Episcopal Church. The original stock of the ancient Church left in Bohemia and Moravia,--eight hundred thousand reduced from four millions,--returned sullenly to a formal obedience to the Church of Rome, and today the Czechs are but nominal adherents of the Roman Catholic Church.

In January, 1919, half a millenium since their first ultimatum to Rome, a Congress of the Bohemian Roman Catholic priests held in Prague adopted resolutions demanding the free election of bishops, the abolition of the rule of celibacy among the clergy, the preparation of a Book of Prayer in the mother-tongue and the use of that tongue in religious services, and an adequate system of education for the clergy. Thirty thousand women signed a memorial in favor of the marriage of the priests.

The Slovaks

The fringes of the Czech race, spreading southeastward along the foot of the Carpathian mountains, form a sub-race called the Slovaks,--a remnant of the Moravian population which passed under Magyar rule in the eleventh century. [7/8] They are historically interesting for having made the tinware of Europe in the Middle Ages, wandering from country to country, and in England called "Tinkers." They have struggled against the Magyars, or Hungarians, deploying out upon the plains of Hungary, occupying the Hungarian province of Slovakia, but never enjoying a definite land of their own,--their race and nationality denied by their oppressors. With the determination to "Magyarize" the Slovaks, the Hungarian government persistently denied them all racial privileges. The use of their own language was restricted by law, and they were deprived of the most ordinary educational facilities. Prior to the recent war, there was not, among these three millions of people, a single Slovak school receiving government support. Though entitled to forty members in the Hungarian Parliament, the Slovaks were never able to elect more than five. A Slovak land-owner could be forced, at any time, to sell his real estate to any person designated by the State. Even the Slovak press was systematically persecuted in Hungary, and today there are more Slovak papers in the United States than in the home-land. These papers were refused postal privileges in Hungary for the very significant reason that they were regarded by the Hungarian government as a distinct menace. No wonder that the Slovaks have sought a haven of refuge in the United States, or that, on arrival, they bear the pitiable marks of an oppressed people--poverty and ignorance!

In the home-land, the war has brought them relief, for the Czechs have espoused their cause, and have taken them under their strong brotherly arm. From this relationship comes the compound name, Czecho‑Slovaks. [8/9] The Slovaks are divided in religion, two-thirds being Roman Catholic, a portion Lutheran, and a smaller portion Eastern Orthodox. The strongly nationalistic Slovaks are Roman Catholic, and one of the remarkable signs of these times is the unity of national purpose which exists between the liberal freethinking Czechs, and the zealous Roman Catholic Slovaks.

A Modern “Anabasis”

The part played in the recent war by the Czecho-Slovaks has been one of the most romantic chapters of modern history,--these people are always doing romantic things of great importance,--their escape from the Austrian army into which they had been forcibly pressed. The thousands who escaped into Serbia were hurled back with the Serbian army across the desolate mountains of Albania, the remnant of half their number were soon found fighting in the Alps with the Italian army. The thousands upon thousands who escaped by pretended surrender to the Russians, formed themselves into splendidly organized troops, and before the world could believe it, Czecho-Slovak regiments having already prevented the spread of German influence eastward from Russia proper, were marching across Siberia with the firm determination to embark on the Pacific coast, and, by way of America and the Atlantic, find their way into French brigades, fighting the enemy on the western front. Halted in their way, the Czecho-Slovak armies yet stretch nearly around the world, amazingly brave and swift and resourceful. There is not its parallel in history. And the strange thing, too, is that they have carried with them wherever their regiments are stationed, libraries of books, full orchestras [9/10] and regimental bands, and all the equipment of outdoor gymnasium work, thousands and thousands of men reading and singing and playing instruments of music, then fighting fiercely beyond belief, relaxing in spare moments to play athletic games and exercise in rythmic calisthenic work which is their peculiar pride. As Olive Gilbreath has written, "How tell the tale of the Czechs without seeming legend? One cannot tell the truth with any hope of being believed!"

The great war is over. On September 3, 1918, the United States Government, following the Governments of France, Italy and Great Britain, recognized the Czecho-Slovaks as an independent nation. On October 12, the entire population of the new Czecho-Slovakia cut themselves off from the crumbling Empire of Austria-Hungary by organizing a Republic and electing Thomas G. Masaryk president. The world now beheld a remarkable spectacle: in Austria-Hungary twelve million people establishing a stable government in alliance with the nations fighting Austria-Hungary, maintaining perfect order at home, while the president was busy in America establishing the world relations of the new Republic. On October 26, in Independence Hall, "the cradle of Liberty," Philadelphia, President Masaryk seated in the chair in which George Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention, signed the new Declaration of Independence, the new national flag with its two broad stripes, white and red, fluttering to the breeze with the American stars and stripes.

The Czechs in America

Quietly, unostentatiously, the Czechs in our land, patriotic Americans almost to a man, are steadily acquiring full citizenship, continuing their course of a generation of Americanization. [11/12] While glad of their native land's final restoration to its former glory, and rejoicing with their brothers and cousins in their new republic, they themselves love the United States of America.

They entered the stream of American immigration at a very early date, and are scattered widely over the country from the Connecticut Valley and Bohemia, New York, to Moravia, Texas, and Seattle, Oregon. They are settled as prosperous farmers in the northwestern states; they are in our great cities as skilled laborers, tailors, carpenters, machinists, bakers, and cigarmakers. They are thrifty and honest, law-abiding, careful of their children, and as a rule are property-owners. Indeed, in New York, Chicago and Cleveland many have become wealthy. The New York City tenement inspectors report that the Czechs may be called the cleanest poor people in the city, but they remain poor but one generation. Music is their passion, and hardly a family can be found without a piano and one or two violins. The names of the Bohemian composers Smetana and Dvorzak are familiar to every lover of music in America. The boys are almost without exception excellent singers, above the average, wonderful choir-boys right in our very midst, and mostly not going to any church. Ask a Czech confidentially what is his religion, and he will answer you as though speaking of a lost cause, "The John Hus Church." That is to say, these are children of an ancient sister Episcopal Church, and we have not known it until today; we scarcely know it or believe it now. These people, therefore, are not to be reached by our Church like those of any other people of foreign birth.

An Independent Race

[13] The first immigration from Bohemia to the United States was after the revolution of 1848 in Austria, and the Czechs who came, left their native country because of political dissatisfaction. These were well-to-do merchants and other business men and scholars who settled in the Middle West. The later immigration, both of Czechs and Slovaks, occurred during the thirty years from 1880 to 1910, and these people came on account of intolerable conditions at home for the working man and farmer. They came into this country in vast hordes--men, women and children--settling first in New York, Cleveland and Chicago, and later spreading out to smaller cities or farmlands in the East or Middle West. Living in colonies, they have naturally done their own banking, and had their own doctors, lawyers and publishers. The Slovaks have been inclined to build their own churches, especially Roman Catholics who have brought their priests from the old country. The Czechs have, on the contrary, fought shy of any Church, and have been content with their own Sokol or social community organization. In cities in New York, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Oklahoma and the Dakotas, are half a million Czechs, all unchurched.

A Unique Opportunity

The field of our Church among the three-quarters of a million or more Czechs and their children in America, is almost without limit. It is indeed white already to harvest. The Roman Catholic Church is powerless to reach these people, except now and then when a tactful Roman priest can gather a congregation and hold them for the period while one generation grows up into the "freethinking" age. Entire communities numbering [13/14] thousands of souls have been abandoned as hopeless. There is an organization of freethinkers who carry on an atheistic propaganda with the express purpose of destroying all Christian faith in the minds of the young. Their spirit has been poisoned by the adversity of history, and they act as those who have been deprived of their right to believe in a God. The Czechs, however, possess an inherent spiritual hunger for the sacraments, and a desire for uprightness of life and a clean conscience, even though they have been described as "the most unreligious of all immigrants in the United States." In this country, the Protestant missions among them have succeeded best when they have used personal persuasion and a rational appeal based on the ethics of life. Institutional and neighborhood settlement work among them by some Protestant missions has also been productive of results, but the principal reason for any congregation is the fact that there is a minister who can marry them and baptize their children, this sacramental tie being the main bond to the church in Bohemia. Another very prevalent reason for sending their children to Protestant Sunday Schools has been to learn the English language and American customs. The bulk of these people here, however, remain untouched by religious work. Social service will not coax them into the Church, for in almost every group of fifty or more families they supply themselves with a neighborhood centre and build their own community house, with gymnastics and calisthenics for both boys and girls, and gatherings for singing and other social exercises. In the large cities they even have their own "movies". Sunday is the great family gathering day, and one of [15/16] their chief grounds of opposition to the children going to Sunday School, is that it takes the children away from home just when the grandparents are making a visit, or when the cousins are having an all-day picnic out in the country, or it may be that the father wants to take his boy off fishing with him.

The Protestant work among the Slovaks in the United States is very small. The Slovak Lutherans have organized themselves into the Slovak Evangelical Lutheran Synod of America, with some twelve thousand members, principally in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Illinois. One of the American Lutheran Synods reports a scattered work among the Slovaks in which there are thirteen self-supporting congregations and twenty-five missions with a total membership of 2,500. The few Slovak Orthodox in this country generally seek an Episcopal Church, saying, "It is the same as ours," but their usual experience is that they are not recognized and so drift into the Roman Catholic Church where they find the majority of their fellow-countrymen. Of the half million Slovaks in the United States it may safely be said that, with the exception of a few thousands, all are loyal Roman Catholics.

The Present Need

The figures giving the statistics of the Czechs in the United States are almost startling. Out of a total of 750,000, the Roman Catholic Church can account for only 200,000, and a generous estimate gives the various Protestant organizations working among them less than 50,000. This leaves half a million people unchurched, indifferent to religion, inclined to atheism, and yet only acknowledged by all who become acquainted with them as an upright and morally clean people, but declared to be [16/17] absorbingly interesting and companionable, while the children are fascinating and lovely.

Among the Protestants working among the Czechs in the United States the Presbyterians take first place, with forty-four church buildings, twenty-five hundred members and a number of ministers of native stock. The work is mostly institutional. The largest church is on East Seventy-fourth Street, New York City, with three hundred adult members and nine hundred children. There is also a large Presbyterian Church in Chicago. The Presbyterian Home Missions Board spends annually $20,000 in its Czech work. The Methodists appropriate annually $10,000 on missions among the Czechs in the Western states, maintaining a few small churches. They feel the work to be well worth supporting, and a recent report makes the statement "These are most grateful people. They are slow to change their church affiliations, though they attend our preaching services and seem to enjoy them." The Congregationalists also provide a place in their missions budget for work among the Czechs and have some organized congregations, maintaining also a mission station in Prague for strategic reasons. The Baptists provide an annual appropriation for mission work among the Czechs and a few small churches have been formed. In June, 1919, delegates from sixty-five Protestant churches using the Czech language met in Chicago and organized the Czecho-Slovak Evangelical Union of America, hoping for an increase of strength by co-operation. But the fact is that the Czech people resent any approach by Protestants and generally claim to be Catholics, although but few Roman Catholic priests recognize them as belonging to their own [17/18] congregations. Our own mission antedates all these Protestant missionary efforts, but it was rather a series of sporadic approaches from the Czechs themselves, while our Church as a whole never heeded them.

A Czech Prayer Book

In the year 1855, our Church in Saint Louis tried to reach the Czechs in that city by translating Morning and Evening Prayer, the Litany, and Holy Communion into their own language. This endeavor failed, however, for four reasons: First, because the book was not translated into good and idiomatic Czesky; second, because the book was printed in German text, and although that was what was used in Bohemia, it had been forced upon them by law and was not of their own choice; the Roman text used in "the land of liberty" is the text used in Bohemia today. The third reason for the failure of this partial Prayer Book was that the translators thought the Czechs must be ultra-Protestant because they were anti-Roman, and so were afraid of the strong word "priest," and actually used the word meaning "pastor," so presenting the forbidding aspect of German Protestantism antagonistic to these Catholic and sacramental people. The fourth reason for failure was that the Prayer Book was given to the Czechs in their own language at all. It must be remembered that the Czechs in this land desire to perfect themselves in the English language. The older generation may indeed be limited to their own tongue, but the children are more eager than those of any other race to become Americans in very sense of the word, and their parents press them forward to this end. And it is this second generation which is outdoing their elders in their nonreligious and general anti-church attitude, speaking [18/19] English and fast becoming more American than many children of English stock.

A Typical American Czech

Here is the testimony of a typical Czech: "I am a Czech, and was born in Bohemia and lived there until 1888 when I came to America. That was thirty years ago, and I was seventeen years old. At first I had a hard time, and had to do any kind of work that came along, was painter, butcher, anything to live. I was paid very little. Four of us lived together. We had two rooms, one with two beds, and one we used as a study and sitting room; and we studied too. What helped me most was that I had a fair education in the old country, even knew a little Latin and Greek, and understood the value of education. The first thing I bought in this country was a book. Half of each page was in English and half in Bohemian. I made myself study half a page each night, no matter how tired or hungry I was. Later I took it to Europe and left it with a relative, so that young people coming over here might study and know a little of the language of America before they came. I want my children to be broadminded, and children cannot grow up broadminded if they go to foreign-speaking schools."

Pioneer Work

Two attempts by our Church in the Northwest have been made to take over congregations of Czechs, but no available native priest could be obtained and the work did not progress. Meanwhile the English-speaking children slipped through and away from these attempts to reach them as foreigners. About twenty years ago, hundreds of children came across the railroad tracks to the Sunday School of Grace Church, Chicago, until they crowded all classes. Bright eyed and eager, these were children [19/20] of Czechs, and soon there were from six to eight hundred of them in the Sunday School. These children, especially the boys, seemed from the very start to grasp two fundamental ideas,--America and the Episcopal Church. [* Grace Church was destroyed by fire September 26th, 1915.] The Church of the Good Shepherd, Chicago, is placed now in a community of 25,000 Czechs, and this parish, once made up of purely English stock, is gradually winning its way among the new people who have surrounded it. Although this church is small, yet the prospects for the future are very encouraging. A good proportion of the communicants, some of the Sunday School teachers, children in the Sunday School and boys in the choir, are increasingly from the Americans of the neighborhood who are of Czech parentage. When the Chapel of the Heavenly Rest (old Saint Alban's Church) at 116 East 47th Street, New York, was actively alive, Czech boys and girls, delightful attractive children, found their way into the Sunday School, at first but a few and timorously, and then to the number of two hundred. When the chapel was abandoned, in January, 1903, this most promising work ceased, and how great an opportunity was lost to reach the 50,000 unchurched Czechs in New York City, can never be estimated. Twenty-five years ago, Czech people crossed the old covered bridge from West Springfield, Massachusetts, to Springfield, and sought baptism and marriage from the clergy of Christ Church. Today these people go nowhere to church; they have lapsed from the Church into freethinking. In Westfield, a colony of 500 Czechs was established (now all Americans), and [21/22] for some time the Sunday School of the Church of the Atonement, itself only a mission church, has depended upon these children for a large part of its membership, while the choir has at times been wholly made up of them. About fifty of these have come into the Church through confirmation. Before the freethinking propaganda reached its present strength, the tendency of the Czechs was toward the Episcopal Church, for they grasped its Catholic and missionary nature. But several circumstances worked against them. First, our people did not recognize them, and classed them as foreigners, presumably Roman Catholic. Second, when they did attend our services they were unable to comprehend the office of Morning Prayer; the service of Holy Communion would have seemed to them more natural and simple. Third, rented pews, with the exclusive atmosphere of cushions and carpets connected with some of the Episcopal churches through whose doors they peered, seemed to forbid their entrance. Although their children might attend Sunday School, yet they themselves might not attend church, and the children grew up apart from the Church itself. Much of this happened a quarter of a century ago, and today some of these very children are good American citizens, many of them exceedingly prosperous, and most of them parents and grandparents with a younger generation of non-church-going people.

Surely the challenge to the Episcopal Church rings out with a clear call, and our answer, though belated, must be made strong and vital. The fact that our mission to these people has faded into obscurity, so that they seem a new and strange species, emphasizes all the more the importance of arousing ourselves to the pressing need of the moment. [22/23] The Czechs must be reached by us, or by none. They will turn to us again; why not take them now? They have, in the past, turned toward us eagerly, yet with diffidence. Have we lost them forever?

Practical Suggestions

Three considerations are to be kept in mind if we are to do our duty in this mission to the Czechs.

1. The English language must be used, for the Czechs in the United States are Americans of the Americans. In crowded communities the use of bilingual service books and tracts might be of much value for the older and more conservative men and women born in Bohemia. But it must be remembered that the Czechs were the first of all the Slavic immigrants, and they are in their second and third generation in this land.

2. Christianity must be placed before the Czechs in its sacramental aspect. Baptism, Confirmation, Holy Communion, Marriage--these are the normal functions of the Church in their eyes. Preaching, if it be of a reasoned and practical nature, will reach them; but not emotional and fervid exhortation. Morning Prayer is utterly confusing to them, with its excessive ritual of continually rising, kneeling, and then sitting again. The Holy Communion seems simple and makes a natural appeal, for they have an instinct of long inheritance for the ministry of the Eucharist. Then, too, it must be frankly granted that the altars must be high, with candles, and a ritual which they understand as sincere and devout.

3. Our work among the Czechs must be distinctly religious. Their own social-service work among their own people is far in advance of the institutional work [23/24] of most religious missions, and they do not need this form of ministration, indeed they could teach us a good deal. The adults have studied the Bible with the books of Ingersoll in their hands, and the "higher criticism" of the Old Testament is well established in their minds. Their skepticism extends also to the New Testament and the Gospel in general, so that Sunday School work among their children, and the presentation of the Church's message as a whole, must be through the faithful administration of the priestly office. This means not only the celebration of the Sacraments, but the pastoral work of visiting the sick in hospitals and homes, caring for the children, and having children's festivals in the church on all the great festal days of the Christian year.

So we come finally to the definite and promising field of our Church--the conversion of the children to primitive Catholic Christianity. What is needed is the planting of Sunday Schools, or rather children's churches, within Czech colonies, with priests in charge who understand something of the history of the ancient Bohemian Church; who will be uncontroversial in their relations with parents; and who, understanding children and using the English language wholly in their work, will minister to them in children's Eucharists, baptizing and preparing them for confirmation in a naive way as though there were no thinkable alternative.

They were, centuries ago, a religious people, and in the young this inheritance comes forth in an eagerness of hunger and a responsiveness to the Gospel that ought to shame us that they are so unshepherded. Had we done this a generation ago, we had won many [24/25] thousands. But even now the way is open, and an alluring future beckons us on. It may yet be brought about that in Bohemia even, due to our enthusiasm and loyal espousal of their cause, their ancient national Episcopal Church will be re-established while, in their adopted land here, they may become good and consistent communicants of our Church. When the chalice is administered to a child of the Czechs in Holy Communion in some parish church of ours, there rushes over the mind and heart of the parent, perhaps in the congregation and, if not then, surely at home, the story of the ancient chalice of the Czechs, the free Communion of the people, and the right of spiritual liberty in the Church of Christ.

A writer describes the scene when Czecho-Slovak troops passing through England attended service recently in Winchester Cathedral.

"Thousands of men in strange uniforms with war-worn banners passed in slow step into the great cathedral. Keen men with sad, earnest faces filled the nave. When the anthem was ended, the clergy paused, and then, in splendid accord, the Czechs sang in their own tongue a rendering of our national anthem, followed by their own national hymn, 'Kde domov muj?' ('Where Is My Home?') The chants they sang with their fierce expressive rendering were the war-songs of the Hussites. They bore the chalice on their banners, and each wore the same chalice on his shoulder straps. The chalice signified the right their ancestors fought for, to take the cup in the Holy Communion."

Copies of this leaflet may be obtained from the Literature Department, Church Missions House, 281 Fourth Avenue, New York, N. Y., by asking for No. 1510.