In this brief study Canon DeMille has attempted to do two things--to tell the story of Bishop Barry's episcopate, and to sketch a portrait of the man himself. I should like to add one more touch to this picture.

Some years ago a good friend gave Bishop Barry two thousand dollars with which to install air-conditioning in his car. Since the Bishop of Albany spends one-twelfth of his time in a car, this was a highly practical gift. The Bishop accepted the money, characteristically "found" another thousand, and built sidewalks around the cathedral. An excellent subtitle for Canon DeMille's sketch might well be "Portrait of a Generous Man."

+ Allen Brown

BishopSt. Andrew's Day, 1961

"We have come to the end of an era." These are the words the present Bishop of Albany addressed to the writer of these pages on the day of Bishop Barry's funeral, and they may well serve as a text for this brief account of a remarkable episcopate. On May 2, 1945, the Reverend Frederick Lehrle Barry was elected Bishop Coadjutor of Albany. He was then forty-seven years old, and had been a priest for twenty years. His rise in the profession had been rapid. Beginning as curate to the Reverend Wallace Gardner at St. Paul's, Flatbush, he had moved from there to the rectorate of St. Gabriel's, Hollis, and then to St. John's, Bridgeport, Connecticut. At the time of his election as bishop, he was rector of the great parish of St. Luke's, Evanston, Illinois.

Although his election was accomplished on the second ballot, it was the climax and the conclusion of a hard-fought battle in which party lines were sharply drawn. The full story of that election cannot vet be told; suffice it here to say that he was elected because the majority of the clergy of the Diocese were resolved to continue the tradition that the Bishop of Albany should be a man sound in the Catholic faith.

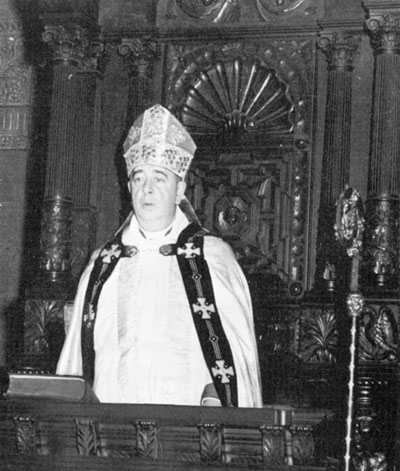

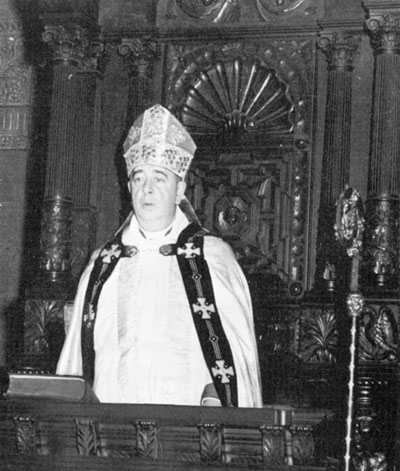

None of those who were present will ever forget the scene at the Cathedral of All Saints on St. Peter's Day, June 29, 1945, when Frederick Barry was consecrated a bishop in the Church of God. The Most Reverend Henry St. George Tucker, Presiding Bishop, was the chief consecrator, assisted by Bishop Oldham, Diocesan of Albany, and Bishop Stires, retired Bishop of Long Island, who had ordained Frederick Barry to the priesthood. It was a magnificent demonstration of the best traditions of the Diocese and the Cathedral.

Bishop Barry became coadjutor in a diocese which was far from healthy. There was a gaping rift in churchmanship, largely the result of the recent election. The Diocese had still to pull itself out of the financial morass of the Great Depression, and recovery was handicapped by a lack of communication between Bishop and clergy. Bishop Oldham was a man of brilliant mind, widely and well read, one of the few great preachers in the Episcopal Church, and a statesman bishop in the affairs of the Church at large, but he had never been at home in small churches, and Albany is to a large extent a [1/2] rural diocese. Dignified and imposing in public appearance, Bishop Oldham was nevertheless a shy man, and as so often happens, his shyness tended to take the form of stiffness. He never received credit for his secret generosity to his clergy and only his intimates knew his real charm. The net result was a lack of cordiality between the Bishop and his clergy.

To the new Coadjutor was assigned jurisdiction over the missionary work of the Diocese. His first endeavor in this field was to restore contact between Bishop and country priests. Essentially a friendly man, who loved to have people around him, gifted with a tremendous and quite unconscious charm, Bishop Barry adopted a policy of dropping informally into isolated country rectories, and by the warmth of his personality making the priest feel that his Bishop was also his friend--a generous and sympathizing friend. It is significant that in his first address as coadjutor to the Convention of the Diocese he struck this keynote:

"May I bear testimony to the faithful service of our missionary clergy. God has given to few men the ability--the spiritual stamina--the imagination--to serve in these most difficult areas of the Church's work and remain content. But in place after place I find priests who love their Lord and serve him by loving folks. They stand as wholesome examples and stamp the work in the rural areas with the seal of importance and significance."

Bishop Barry was a bachelor. During the first years of his coadjutorship he lived in an apartment on Washington Avenue within a block of the office. As he left the office of an afternoon, it was his almost invariable custom to invite any priest who happened to be around to walk over to the apartment for a smoke and a cocktail. This may sound trivial; it was not. It was an expression of the changed conception of the proper relationship of bishop and parish priest. That he was so successful in improving that relationship depended upon the peculiar genius of Frederick Barry. Six foot tall, and weighing well over two hundred pounds, he was a man of magnificent presence and great dignity. One was always conscious of his warm friendliness, but one never took liberties. He could unbend and still be the Bishop.

Quite aware of the tensions resulting from his election, Bishop Barry deliberately set about easing those tensions. Groups of clergy carefully picked to represent varying schools of thought were invited to the apartment or to lunch at the [2/3] Fort Orange Club. Papers were written and discussed. Differences of opinion were plainly stated, and a sharp gust of fresh air blew through the heated atmosphere. Largely because of this, in a few years the "churchmanship" issue had almost disappeared from the Diocese of Albany. And here a word must be said about Bishop Barry's own churchmanship. It was noised throughout the Church that he had been elected on a platform of "high church." Immediately after his consecration he began to be pelted with letters of application from priests who were sure that now Albany was to be the happy hunting ground of the extremists. They were doomed to disappointment. Bishop Barry was a Prayer Book Catholic in the best sense of that much misused word. Quite clear in his loyalty to the Catholic conception of the Church as set forth in the Book of Common Prayer, he detested narrow partisanship and went out of his way to conform to parish customs on his visitations. In 1945, both the Episcopal Evangelical Fellowship and the American Church Union had local chapters in the Diocese of Albany. Bishop Barry quietly persuaded both of them to disband.

Frederick Barry was a man of imagination. Incidentally, this was one of his own favorite phrases. "So-and-so has imagination," he would say. I am sure that he came into the Diocese with the firm conviction that Albany was still in a rut of Depression mentality, and that his particular function was to lift it out of the rut. After two years of looking the situation over, he began to have ideas--new and startling ideas. He once said to me, with that charming ability to laugh at himself that was one of his leading traits, "George, I have so many ideas that at least ten per cent are bound to be good." His address as Coadjutor to the Convention of 1948 marks the beginning of that program of diocesan advancement which he regarded as his life work. In this address, he proposed three forward steps to be taken. One, there should be a definite minimum salary for clergy of $3,000 a year, plus house and utilities, plus travel allowance. Two, there should be a suffragan bishop located in the "North Country." Three, there must be a considerable amount of new work--missions opened in communities not yet reached by the Church.

To carry out these objectives, he asked the Diocese to raise $300,000, to be spent over a 10-year period. By May, 1949, [3/4] this, the first of Bishop Barry's campaigns, had produced $125,000.

In this whole episode we can see at once the strength and some of the weaknesses of Bishop Barry. The campaign, itself, seemed to some of the older men of the Diocese, men who had weathered the financial storms of the Depression, an impossibility. But not so to Frederick Barry, and it was due to the impact of his personality that this large amount was raised. The sums thus raised were used, first of all, to increase the stipends of the missionary clergy. Parenthetically, let us note here that increase of stipends for all the clergy was one of the Bishop's continuing concerns, and that by the end of his episcopate a minimum of $4,000 had been established. Some new work was started--at North Creek and Tahawus in the Adirondacks, and at Cobleskill, which had limped along on one foot for decades. These were gains. But the status of Deanery missionaries was indefinite, and unfortunate choices were made in personnel. After a few years the project was quietly dropped. There never was a Suffragan living in the "North Country." These failures were definitely due to a weakness in the Bishop--a weakness which can best be described as a lack of cold judgment. His ideas were magnificent and daring in the round, but sometimes lacked precision in the carrying out. But it was part of Frederick Barry's charm that there was nothing cold about the man.

In December, 1949, Bishop Oldham reached the age of canonical retirement, and Frederick Barry became fourth Bishop of Albany. He was enthroned on the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul, January 25, 1950. Now, the Bishop's throne in the Cathedral of All Saints is a magnificent and towering erection, and Bishop Barry looked magnificent in it. But he somehow felt that it was ostentatious, and with the modesty which was part of his makeup flatly refused to use it for years. The Bishop said to me one day, "George, you will probably outlive me, and you will write the history of my episcopate. Here is a good sentence to start it. The fourth Bishop of Albany came in like a bull in a china shop."

On May 15, 1950, the Bishop opened his first Convention as Diocesan Bishop. It is significant that this Convention, shattering all precedent, was held not at the Cathedral, but at the Lake Placid Club. The basic reason for this change originated with the Bishop and was due to his conviction that by meeting together under one roof, eating together, [4/5] having opportunities for informal social contacts, the delegates, and especially the lay delegates, would become less a herd of sheep and more an intelligent legislative body.

This first of the Lake Placid conventions was the stormiest of Bishop Barry's whole episcopate. As soon as he took office as diocesan, Bishop Barry had asked for the assistance of a suffragan, and one phase of the Convention was the election of such a person. The election was from beginning to end a chapter of errors. There was no principle involved, as there had been in the election of the Bishop himself. There was no one outstanding candidate nor great personality to command a majority of the votes. Eight men were nominated, but eventually the election boiled down to a contest between Dean Kennedy of the Cathedral and the Reverend John Higgins, then of Minneapolis. The ninth ballot found clergy and laity deadlocked. The Bishop, therefore, in accordance with a written statement he had made previous to the Convention, withdrew his request for a suffragan. That night after adjournment a series of hurried conferences was held, with the result that a small group of the leading clergy of the Diocese visited the Bishop and begged him to reopen the matter. He consented to do so on the condition that he be allowed to make a nomination, himself--a nomination which no one was bound to support. On this understanding, the Bishop next morning reopened the election and nominated the Reverend David E. Richards, curate of St. George's Church, Schenectady, who was then elected by a large majority.

This whole imbroglio was reported outside the Diocese as a piece of subtle politics on the part of the Bishop. It was nothing of the sort. The Bishop could be a great diplomat, but he had not a bit of the trickiness nor the subtlety of the politician. His nomination of David Richards was completely characteristic of the impulsiveness of the Bishop. No one can begin to understand Frederick Barry who does not realize that under a surface sophistication lay a basic stratum of extremely simple, almost naive religion. The Bishop was firmly convinced that on the night of May 16 the Holy Ghost himself had whispered in his ear the word "Richards."

In his Convention address of this same crucial year, the following important sentence appears:

"We must face the fact that this Diocese faces greater cost in its administration."

One of the jobs that now lay before Bishop Barry was that of bringing the Diocese out of the horse and buggy period of administration. In the days of Bishop Nelson, the diocesan staff had consisted of one bishop and one part-time priest-secretary. The transition to a larger staff had begun under Bishop Oldham, who, handicapped as he always was by a lack of funds, had bought for a diocesan office an old residence on South Swan Street. Under Bishop Oldham worked as secretary Miss Emily Gnagey, who performed prodigies of work, and an archdeacon, the Venerable Guy Harte Purdy, who knew the Diocese inside and out. At one time there had also been an Executive Secretary and a Director of Religious Education but the Depression had killed both jobs. Bishop Barry's first step in enlarging the staff was to bring in as Executive Secretary Mr. Walter Loecher. Mr. Loecher was a first-class bookkeeper and a meticulously exact person, whose figures were always in order and at his fingertips. This change had been made while Bishop Barry was co-adjutor. Now, in 1950, there was a great blossoming out of staff. The Reverend J. Alan diPretoro was appointed full-time hospital chaplain and in nine years of magnificent service made that office a permanent necessity. In the same year, the Reverend George E. DeMille became part-time Director of Theological Education. This function became necessary because of the great increase in candidates for the ministry--an increase due in part to the number of men coming out of the Army after Korea, and in part to the Bishop's ability to attract young people into the ministry. In the 1930's, the average number of postulants and candidates at any one time was six. In 1950 there were thirty-eight. I shall have occasion to cite later the great increase in diocesan income during this episcopate. Here are some figures of perhaps great significance. Between 1930 and 1939 there were thirty-nine priests ordained. In the next decade the number had dropped to seventeen. But between 1950 and 1959 it shot up to sixty-two. This was no doubt partly due to the increase in candidates to the ministry throughout the Church during this period, but it was also partly due to the warm personality of the Diocesan.

The years of Bishop Barry's episcopate were just those years during which the Episcopal Church was giving more and more attention to the vital field of religious education. In 1953 the Bishop appointed a full-time director of this department, the Reverend Edward T. H. Williams, who [6/7] during his five years of service made the whole Diocese aware as never before of the importance of Church schools. The last addition to the staff came in 1954 when the Reverend Ivan H. Ball became Director of Promotion. He turned out to have a touch of genius in organizing parish financial canvases.

Now it must be borne in mind that the Bishop was not in the least interested in building up a bureaucracy, but rather in creating agencies which would give the parish priest the services--the reserves--needed in his front-line work. Something must also be said about the Bishop's relations with his staff. He was a man who detested routine, who hated details, who thought in large and sweeping terms and expected his staff to fill in gaps. This made him an excellent man to work for. He left men free to do and work in their own way--an attitude which was one of the reasons why he was surrounded by a devotedly loyal staff.

When Bishop Barry first became coadjutor, he was inclined to be rather cold to the Cathedral. Gradually, he came to love it. The Convention of 1951 marked the beginning of his very practical efforts to do something for that grand building. At his initiative, at that Convention a Fabric Fund was started which eventually produced $165,000. This was used to accomplish four important improvements in the structure:

1. The laying of a new concrete floor, incorporating radiant heat.

2. Plastering the soot-stained interior walls.

3. Rebuilding the organ.

4. Reconstruction of the vast space under the nave, which was in time to be a parish hall.

This was the first construction work on the Cathedral fabric since the completion of the choir in 1904. In the following year, the Convention, again at the Bishop's initiative, voted a special levy of 2 per cent on the current expenses of all parishes and missions, to be turned over to the Cathedral for maintenance purposes.

It was fortunate for Frederick Barry, with his temperament, that he became Bishop of Albany at a time when the Church was in one of its periods of expansion. To Bishop Oldham had fallen the difficult task of guiding the Diocese through the Depression, when the watchword was merely [7/8] "hold the line." To Bishop Barry fell the happier task of heading an era of building.

In the Capital area this period begins with the erection of Grace Church, Albany, the first venture into modern architecture within the Diocese. This was followed in rapid succession by the church, parish house and rectory of St. Michael's, Colonie, which grew in three years from a group of people holding services in a fire house to a congregation of over two hundred persons. St. John's, Troy, and St. Andrew's, Albany, built large new parish houses. St. George's, Schenectady, was reconstructed with exquisite tact under the direction of the architects of the Williamsburg Restoration. Two daughters of this parish, St. Stephen's and St. Paul's, both of Schenectady, had splendid new churches. St. Stephen's, Elsmere, built a church and a parish house. St. Matthew's, Latham, a daughter of St. John's, Troy, built a parish house to contain one of the largest church schools in the Diocese. All of these, it is to be noted, were in the Troy-Albany-Schenectady area, and were partly the result of the blossoming of the suburbs.

But the building of the period was not confined to this area. We have mentioned the new missions at North Creek and Tahawus. The Reverend Harold Kaulfuss resigned as Rector of Gloversville to found a new parish--the first in Hamilton County--at Lake Pleasant, and before his death it had a small church and rectory. The parish of the Messiah, Glens Falls, sponsored and built St. Timothy's Church, Moreau. In all, twelve new churches, large and small, nineteen parish houses, eleven rectories were built between 1945 and 1960. There had not been, since the period following the American Revolution, such an era of expansion in this territory.

In 1954 the Bishop was able to report the following figures to the Convention of that year:

MISSION QUOTAS PAID 1945 $51,388.20

1953 $128,824.17

This was, of course, an indication of the increased prosperity of the country at large; but it was also an indication of the response of the Diocese to the leadership of Frederick Barry.

In 1955, Frederick Barry had been ten years a bishop in [8/9] the Church of God. There was a widespread feeling in the Diocese that something should be done to mark the year. Unselfishly, the Bishop asked that there he nothing in the way of a personal gift, but that the anniversary rather be marked by something that would redound to the glory of the Diocese and the advancement of the Church. Two major things were, therefore, planned for this year. The first was diocesan. The National Council had some time before set up a survey service which was equipped to go into a Diocese and make a complete study of its activities and its environment, with recommendations for constructive advances. This agency was employed, and for several months the experts of the survey were in the Diocese. Every parish and mission was surveyed, and appropriate recommendations were made. This survey cost the Diocese some $12,000. It produced seven bulky volumes of analysis and findings. I believe that they are still somewhere on file.

A second activity of this year was hailed by The Living Church as the most notable event of 1955 in the Life of Protestant Episcopal Church. This was the Church and Work Congress. Springing from the fertile brain of the Reverend Bradford Barnham, Rector of St. John's, Troy, it was ably administered by Bishop Richards. In October 1955 representatives of the professions--law, medicine, teaching--men in government service, business executives, and labor leaders assembled in Albany for a week of conferences. The chief speakers were Arnold Toynbee, the eminent British historian, and Bishop Emrich of Michigan. Formal speeches concluded, the Congress divided itself into occupational seminars, the purpose of which was to examine the work of each group in the light of Christian philosophy. Eventually, a volume was published entitled Man At Work In God's World, which contained the principal addresses and brief summaries of the group discussions. It was a successful attempt to bring the ancient Church into touch with the modern, work-a-day world.

At the Convention of the same year, 1955, the beginning was made of two things which were perhaps of more lasting value to the Diocese than were Survey or Congress. A committee was appointed to investigate the whole organizational structure of the Diocese and to make recommendations for a reorganization. Behind this lies a history. The first Bishop of Albany, William Croswell Doane, was a man of creative [9/10] genius. But he seems to have had a positive mania for "Boards." In 1955 the organization of the Diocese was a chaos. First, there was a Standing Committee, in theory the Bishop's council of advice, with extensive legal powers but no real share in administration. This had been supplemented under Bishop Oldham by the formation of the Diocesan Council, which was supposed to act as a sort of Bishop's cabinet. But it had become so large, with its twenty odd members, that it was basically a rubber stamp. The Board of Missions was a corporation controlling a large endowment and supposedly advising on the appointment of missionaries and the allocation of stipends. It was frequently and necessarily bypassed. And then there was a weedy growth of secondary boards, some of which met once a year to appropriate money already allocated by certain wills. The "Manning Commission," the body which investigated this tangle, found that some of these boards had been so forgotten that they no longer had any legal membership. This was the augean stable that must be cleaned out.

In 1957, the Committee on Reorganization presented a careful report, the net result of which was the abolition by law of a number of useless boards and the formation of a new Diocesan Council, smaller in number and with very real powers and duties. This has proved in practice to be an active and intelligent governing body. In the early 1930's, Bishop Oldham, faced with the problem of finding office space for an increasing diocesan staff and having very little money to work with, had managed to buy 68 South Swan Street. We have mentioned the great increase in diocesan personnel under Bishop Barry. By 1956, two bishops and their secretaries, the Department of Christian Education, the Department of Audio-Visual Aids, the Department of Promotion, and the Diocesan Bookstore--all were trying to carry on their work in eight rooms. The building was literally bursting at the seams. Eventually, it was determined, after considering and rejecting several plans, to buy additional buildings adjoining 68 and to reconstruct the whole. This work was completed and the offices and apartments occupied in the fall of 1958. The cost was met for the time being by a special assessment on the parishes and missions.

Unlike his predecessor, who had been known throughout the Anglican Communion for his leadership in national and international gatherings, Bishop Barry was first and last the [10/11] Bishop of Albany. It was, however, impossible that a man of his striking and magnetic personality should fail to become a figure in the Church at large. In 1956, he was elected President of the Second Province. As everyone knows, the provincial system is a sort of ecclesiastical fifth wheel. Neither the provincial synod nor its President have any very real powers. But the Bishop had little desire to be an ornamental figurehead, and he began to search out ways to make his new office meaningful. His trip to Haiti in 1958 was a valid attempt to make the Province aware of its missionary responsibility for Haiti, which is part of the Province. Meanwhile, he was beginning to be the center of a group of the younger bishops and his influence was increasingly felt in the House of Bishops. The high spot of his contact with his episcopal brethren came in 1959 when the House of Bishops met at Cooperstown. Here Bishop Barry was in his glory. Generous and expansive, he loved to play the host and did it very well indeed.

In 1957, the Suffragan of the Diocese, Bishop Richards, was elected by the House of Bishops the first Missionary Bishop of Central America. It was characteristic of Bishop Barry that, aware that he had laid heavy financial burdens on his Diocese, he announced that for a time he would carry on the administration without other episcopal assistance. But it was strongly pressed upon him that this would be equivalent to committing suicide. Not since 1928 had it been possible for the Bishop of Albany to carry by himself the load of diocesan administration. On October 22, 1958, the new Diocesan Council resolved that there should be immediate provision for a suffragan bishop. Therefore, at the Convention which met in the following week, the Bishop asked for such assistance.

The election which followed was a clear indication of the way in which Bishop Barry had healed the wounds of party warfare and built up diocesan solidarity. On October 28, 1958, a special Convention met at the Cathedral to elect a new suffragan. Nineteen men were placed in nomination, but the very first ballot made it evident that only two of them had the faintest chance of election. These two were the Very Reverend Allen W. Brown, Dean of the Cathedral, and the Reverend Charles B. Persell, Jr., rector of St. John's Church, Massena. On the third ballot Dean Brown was elected. There were several notable things about this election. The first was that Bishop Barry, having learned by experience, [11/12] kept his hands completely off. The second was the total lack of political activity or bitter feeling. The third was the fact that for the first time in its history, the Diocese of Albany had elected one of its own sons to the episcopate. Dean Brown had been ordained in the Diocese and had spent his entire ministry within its confines. He was consecrated Bishop on February 22, 1959, in St. John's Church, Ogdensburg. This was the first consecration performed by the Most Reverend Arthur C. Lichtenberger as Presiding Bishop.

In the fall of 1959 it was becoming painfully apparent that in spite of his robust frame, the Bishop's health was not good. He was visibly wearing out. Having complete confidence in Bishop Brown, he turned over to him more and more of the spade work of the diocesan administration. But Frederick Barry was to accomplish one more great thing for his Diocese. I remember his saying to me back in 1950, "I hope for one thing; that when I leave this Diocese my successor will find its finances adequate to do some real advance work." His last campaign was motivated by this basic idea. Following the Bishop's lead, the Convention of 1959 gave consent to a financial drive to be handled by professional fundraisers with the goal of $900,000. The fund thus raised was to accomplish four specific objectives:

1. The paying off of the debt on the Diocesan headquarters.

2. The construction of a new Child's Hospital. The Hospital, one of the many projects of Bishop Doane, occupied an antiquated building on Elk Street. It had passed through one financial crisis after another and managed to survive, but it was evident that it must have new quarters. But more than this was involved. Bishop Barry, with his inveterate characteristic of seeing visions, saw the new hospital as a center for numerous new works of mercy and charity. The Diocese already owned an admirable site near the Albany Medical Center, on which was located St. Margaret's House for Babies. Here the new hospital was to stand.

3. The formation of a revolving fund to make loans to parishes for major construction.

4. The setting up of a much-needed fund to finance new work. The suburbs of Troy, Albany, and Schenectady were growing rapidly, and it was vital that the Episcopal Church should be ready to erect new parishes in these suburbs.

[13] The building of the new offices had made obsolete and useless the old deanery on Elk Street--for years a "white elephant." The relocation of the hospital freed the old hospital site for sale. Both of these properties were eventually sold to the State of New York. One day while the negotiations were in process, the Bishop walked into the bookstore literally beaming. "Well, George," he chuckled, "I have just earned my year's pay."

"How?" I asked.

"The State has raised its offer for the buildings $10,000--and that is just what I get a year."

In the early months of 1960, the Drive got under way. Now the Bishop really loved the kind of effort that the Drive involved--the innumerable meetings, the rousing addresses, the sense of doing something creative, the piling up of results in tangible and tabulated form, and in this Drive he literally wore himself out. Day after day, he was on the road. Night after night, he galvanized meetings with burning enthusiasm. By June 1960, the Drive had produced, not the sum originally set as a goal, but just over $1,000,000. It was to be Bishop Barry's last achievement for his beloved diocese.

As soon as the Drive was completed, the Bishop left for a trip to Europe which was to last all summer. He returned two weeks sooner than he had planned, and he returned a broken man. For a time, he came every day to the office, but he transacted only the most essential business. What he wanted was not to make decisions but to sit at his desk and to have people come in and talk to him. We learned not to ask for answers. In September, he went to the hospital. I never saw him again.

At the beginning of October, the Diocesan Convention met at Lake Placid, but met under a cloud. Necessary business was transacted, but the uppermost thought in the mind of everyone was the absent Bishop lying in the hospital. On the third day of the Convention when the clergy and laity assembled for the early Eucharist, Bishop Oldham walked in--vested in black. Frederick Barry was dead.

On Friday, October 7, his body was carried to the Cathedral--the Cathedral for which he had done so much--there to lie in state overnight. All through the afternoon, all through the night there was a steady procession of people entering the Cathedral and kneeling in prayer before the closed coffin. On Saturday morning with a packed Cathedral, the requiem [13/14] Eucharist was celebrated by Bishop Brown, with both Bishop Oldham and the Presiding Bishop taking part. It was a model of what a Christian funeral should be--a great cry of triumph over a good soldier of Christ gone to his reward.

We are too close to Frederick Barry to arrive at any final estimate of his worth and his contribution, nor is this writer the person to do it. He had his faults, and I have not attempted to minimize them. I am certain, however, that he was a great bishop, a creative personality, and the most lovable man I ever knew.

Grant him eternal rest, O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon him.