It has always seemed unaccountable to me that so little has been written in record and remembrance of Bishop Williams. Having so many devoted friends and admirers, both among the clergy and laity, whose recollections must be taken from many standpoints, one wonders why so few have been recorded. He was so notable a personality, so great intellectually, officially so prominent, not only in his own diocese, but throughout the United States and abroad; so popular with all classes, and so universally recognized as one of our greatest men by the learned in all professions, how does it happen that some of those whom he educated and instructed with such rare wisdom, whom he guided and helped, have not with gratitude and eloquence paid fitting tribute to so great a character?

Sixteen years ago he died, but, aside from the tributes paid him at his death, and the worthy memorial sermons by Bishop Doane and Dr. Hart, no fitting words have received the story of his life, his work and achievements, his great influence on the development of the church, or told of his strength of character, his loving personality, his simplicity and dignity, or of the wisdom, tact and towering intellect that placed him so far above the average in the estimate of all.

Add to all this the reminiscences of his friends, his personal interest in families and individuals, his brilliant wit and wonderful memory, his skill as a "raconteur," his delightful conversational powers, his faithful friendship for young and old--here is a wealth of material that would furnish pages of interesting reading for the many lovers and admirers of so great a man. He was, as Bishop Doane so aptly characterizes him, "a spiritual Prince."

Many have asked me why I did not write my own recollections of Bishop Williams, because I was so intimately connected with him for very many years, but I have felt that my pen was utterly unworthy of so great a subject, and, if I venture now to do so. it is with the feeling that I cannot attempt to portray his character or his intellectual abilities, but recall only some of the light and ordinary details of a long and useful life. However, as I was from my youth honored with his confidence and affection, what I may have to tell will be largely personal, for which I must be pardoned, as it is all I have to offer. Yet some of it may be interesting as showing how supremely he was [3/4] loved and how closely he attached himself to his people. After his mother's death he was a lonely man with few near relatives, and therefore his affections were largely centered on those bound to him by no ties of blood, but, nevertheless, they were deep and sincere.

Turning backwards many long years one recalls his frequent preaching in old Christ Church on Broad Street, Middletown, where his sermons were a delight to his hearers; always logical, clear as crystal, and in language that a child could comprehend. Later, in the new and present edifice--now Holy Trinity--he preached, but more infrequently, because of his increasing duties, not only as Bishop of Connecticut but as Presiding Bishop.

I well remember on one occasion when he seemed to be especially impressive and earnest as, in his bishop's robes, he stood towering majestically above his hearers, the idea of an archangel flashed through my mind. He was preaching one of his eloquent sermons, the text taken from his favorite St. Paul, and in conclusion, he exclaimed in tones of deep humility: "And yet I am ready to say with St. Paul, having done all these things I am a most miserable sinner."

Again, I recall his officiating at a funeral on Indian Hill Cemetery. It was a beautiful day, the sun setting in exquisite coloring in the west, and everything so quiet and peaceful that it seemed as if we were outside the busy world entirely. Bishop Williams had read the " committal" and then in tones almost exultant and full of belief and faith, raising himself to the full height of his magnificent manhood he pronounced the words, ''I heard a voice from heaven saying unto me--write, 'From henceforth blessed are the dead who die in the Lord,--even so, saith the Spirit, for they rest from their labors." [Note--The popular Captain West, an officer of one of the great steamship lines, told a Philadelphia friend of mine that during a voyage from England to this country, when he was bringing over the wonderful Swedish singer Jenny Lind for, I believe, her first concert tour, she expressed her earnest desire to behold a sunrise at sea. Accordingly, one cloudless morning he had her called at early dawn and she stood tint by his side on deck, silent and motionless, watching every change of shade and until the first golden rays shot up from the horizon. As the sun itself leaped up from the waves, she burst into rapturous song, her deeply religious feeling finding expression in the noble music of Handel's "Messiah." No wonder that Captain West, when describing the scene, should have exclaimed: "No one will ever hear "I Know That My Redeemer Liveth' sung as I heard it that morning."]

I shall never forget that occasion, nor the impression it made on me, for there was such a note of triumph in the tones of his voice, as if he were expressing his own entire belief in his own words, in the presence of God, and utterly unconscious of his surroundings. Never have I listened to a more [4/5] wonderful service, nor heard those inspiring words uttered by mortal lips in such a striking and beautiful manner. Had there been present unbelievers, with hearts of stone, they must have been stirred by the comfort of the text so exquisitely rendered.

On another occasion, an Easter Sunday, a collection was planned to pay the parish floating debt. Bishop Williams was to preach, and before his sermon he simply stated the purpose of the collection, and it would please him very much personally if the congregation would contribute sufficient to free the parish from the last of its indebtedness. After the service the rector, or warden, received a note from a gentleman present, not a Communicant, stating that if the collection was not sufficient he would personally send his check for any deficit, which he did, amounting to about $1,500, remarking afterwards that the bishop wanted the debt paid and so he was glad to do it for his sake.

Some years ago when the Berkeley Divinity School needed funds, I told Bishop Williams I believed, from what had been told me, that Mr. S. would contribute if he asked him to do so. The bishop gave me a note of introduction and I was received cordially and stated the object of my call. He replied, "I am not a churchman, nor have I any connection with the Episcopal Church, though my wife was a communicant, but I know Bishop Williams and admire him, and anything he wants he ought to have. I will give him $1,000 now, and if necessary you can come to me for more."

Another instance, the circumstances of which I am not at liberty to detail, when a very large sum of money was needed for a specific purpose, I asked the bishop to write to a generous friend, stating the case, but it took six month's persuasion on my part to get him to do it, although he constantly said that he would. Finally the letter was sent and the response was instantaneous and the check for $30,000 received within a week.

Let it not be thought that Bishop Williams did these things frequently. On the contrary he seldom asked for money by personal appeal, and disliked to do so immensely. But when he did the result showed that it was looked upon as a privilege to do what such a man desired, because underneath it all lay silent and unexpressed deep love and personal affection that prompted instant response.

Now that Mr. Joseph E. Sheffield of New Haven has long passed to his rest. I can speak of the absolutely confidential and affectionate relations between him and Bishop Williams. Mr. Sheffield [5/6] regarded it as his peculiar privilege and happiness to aid largely in sustaining the work of Bishop Williams in establishing the Berkeley Divinity School and provide for its future endowment, as well as its then present needs. For many years Mr. Sheffield contributed over $5,000 a year out of his private purse in lieu of New Haven & Northampton dividends, which had been suspended on stock which he had given the school, and his generosity relieved the good bishop of many anxious moments.

In reference to this I quote from a confidential letter from Mr. Sheffield to myself, written in 1881, in which he says:--

"The present investment is safe, and while I am able to sign a check the dividends will be regular; and I feel warranted in saying they will in time be much larger. This, again, private and confidential, and only for the good bishop and yourself. I cannot but realize his anxiety for the future income for Berkeley (indeed the present income); I cannot expect to relieve that anxiety, but, if I can lessen it, I feel that it is my bounden duty to do so."

Once Bishop Williams was dining with Mr. Sheffield at his New Haven residence and Mr. Sheffield, who sat opposite, remarked: "Bishop, how well you look. Who is your physician?" And the reply came, "He sits opposite me, sir." The bishop told me the color rose in Mr. Sheffield's face like a girl, so overcome was he at the deep feeling contained in the good bishop's words and the compliment so beautifully expressed.

Turning back to life in Middletown in the 60's and later, one may remember frequently seeing Bishop Williams on the street and seldom alone. Sometimes amid a group of students or walking with two or three; sometimes with the clergy, of whom many were here--Dr. Goodwin, rector of the parish; Drs. Harwood, Coit, Fuller, de Koven, Davies, Gardiner, Townsend, Binney and others; sometimes stopping for a chat at the old rectory (standing on the present site of Holy Trinity Church) and often meeting his lifelong friends of the lay families--Alsop, Johnson, Casey, Jackson, Russell, Glover, Hackstaff, Hubbard, Pelton and many others. Always a smile, a pleasant word, and a handshake, and whether he met Jew or Gentile, Catholic or Protestant, all knew Bishop Williams and called him friend.

In the earlier days of the school, when the learned and genial Dr. Thomas W. Coit lived in Troy, he would come in the spring and autumn to lecture to the students, and it was remarked by some witty person that we could always expect Dr. Coit, [6/7] Connecticut River shad and Barnum's circus at the same time every spring. The bishop's house was always a center, and its hospitality generous and abundant. During the days at home you would find him in his library working, writing or reading, and in the evening during his mother's life, and afterwards, sitting in a rocking chair in the southwest corner of the parlor smoking his cigar and reading or chatting.

When the first company of volunteers, in 1861, left for the seat of war I well remember it drawn up in front of the bishop's house to receive a flag made by the women of Middletown and presented in eloquent words by the bishop. He was loyal to the core to that flag and all through those weary years of strife his voice was heard for the Union.

He never went much into society, though often a welcome and much desired guest at the dinner parties so frequent then in the town. But his devotion to his mother was so dutiful and so beautiful that he found his chief relaxation in her society. After her death Miss Tibbs, an elderly lady who had always lived in his family, kept house for him; later, when her health failed, his cousin. Mrs. Field, looked after his household until his death. I recall years ago a trustees' meeting at his house, interrupted by the luncheon hour, when we adjourned, to the dining room. The bishop, eating but little himself, entertained us by telling some dialect stories of the wittiest character, and in inimitable manner, so that our grave and reverend board was so convulsed with laughter, that we could scarcely eat. No professional actor could have excelled him in accent, pronunciation and gesture, and as one story followed another we enjoyed a treat rarely experienced.

Wherever he happened to be, whether in church, society or meeting of any sort, he was instantly accorded the first place, and was the center of attraction. There was absolutely no question as to his precedence, and it seemed to be taken for granted that it belonged to him; and I may add, not so much on account of his office as because of his acknowledged strength and superiority intellectually. Yet he never assumed this superiority by right of position, or his unusual gifts. In fact, his attitude of mind was humble and not assertive, and he was easy of approach by all. No artificial cloak of dignity was needed to remind one that he was a bishop, and a great man. He did not hedge himself about with any barriers of pride, or intolerance; yet I never saw a man who dared to take advantage of his friendship or simplicity of manner. I have [7/8] met in traveling far and wide, in business and socially, many young and old who knew Bishop Williams, and the fact of our mutual acquaintance seemed at once to create a common bond that put me on a friendly basis that was unique. This experience covers, of course, the bishops of our church, and the clergy, as well as a justice of the supreme court of the United States, statesmen, professional and business men, down to the humblest of the land.

In 1894, before going abroad, I asked the bishop if he would give me some letters of introduction. Calling for them, he said he had concluded to give me one letter which, if presented to any English cleric, would insure me attention and civility, and especially in Scotland he was sure would give me the "entree" to anything, or any place I wished to visit. He instructed me when I visited Lambeth Palace to send the letter with my card to the archbishop's secretary, and, as he expressed it, "You will be shown everything any American layman ever sees, and probably some things they never see."

When I called I asked for the porter (as the bell was answered by a middle-aged woman) and was told he was not in the palace, I then gave her the letter and my card for delivery to the secretary, and when the woman returned she said the secretary had directed her to guide me through the palace. She then explained that she was the wife of the porter, who was absent on his two weeks' holiday, and added: "Are you from Bishop Williams of the United States?" And when I assented she said: "Ah, John will never forgive himself for being absent when any one from Bishop Williams comes here, or any friend of his." This she kept repeating as we journeyed through the palace, showing me every room and thing of interest she could think of, and finally we reached the Lollard's Tower, where she said Bishop Williams would come often to smoke his cigar, and where I think "John" sometimes accompanied him for a chat.

I parted from my faithful guide, leaving her still repeating her tearful regrets that John should be away when any friend of Bishop Williams called. Evidently when he went to England and Scotland in 1884 he had made devoted friends of the old porter and his wife. Such is an illustration of the character of Bishop Williams, who won the respect and love of the lowly, equally with the friendship of the great. The circular letter of introduction I have in my possession and shall always keep as a valued memento.

[9] Returning home, I immediately called on Bishop Williams, finding him seated in the corner of his library reading and wearing the familiar purple dressing gown. He rose and came forward, putting a hand on each shoulder and kissing me on each cheek, saying, "Well, I'm glad to see you home again. I've felt like an old cat that had lost its kitten." Such a welcome, from such a man, I have always considered as one of the events of my life to be most proud of.

Perhaps no event of his life gave him more real enjoyment than his visit to Great Britain in 1884 to participate in the Seabury Centenary, and the account of this together with the services in Connecticut, were published in 1887. In acknowledging the presentation of the staff by the Bishop of Aberdeen, Bishop Williams said:--

"There are times and things concerning which words utterly fail, and must fail, to give utterance to the feelings of the heart, and this let me say, is one of those times--a day that I can never forget, a day for which, though most unworthy of what has been given me, I must always feel the devoutest thankfulness to Almighty God."

I would like to quote the whole page, for what he said is contained within that space. It breathes thankfulness, humility and happiness of spirit, and the prayer that the bond between the Scottish and American churches will, be maintained in the years to come. It is all so characteristic of the man--simple, thankful and eloquent.

Some of his letters from abroad (copies of which I have through the kindness of the Misses Beach of West Hartford) are, of course, very interesting, with many little sparkles of humor, and often sentiment, when he encloses a leaf, a flower, or a bit of heather, with a little story accompanying it, of association with somebody or some thing.

Surely, the church made a wise choice in selecting Bishop Williams to represent it at the Seabury Centenary. Physically and intellectually he made a deep impression, and so noble a presence, so eloquent a preacher, and so well informed, a scholar was indeed a delegate of which America might well be proud.

But with all the honors and hospitality so abundantly showered upon him, it is evident through all his letters that he turned with almost homesick longing to his own people and his own home--counting the days before sailing and arriving in Middletown, much as a schoolboy might count the weeks and days before his home-coming.

So many of the stories and witticisms of Bishop Williams have been published that there is danger of repetition, but a few will not come amiss -as showing the lighter side of his character. In his visitations he suffered many inconveniences and discomforts, though he never complained, and probably a strong, inherited constitution many times saved him from serious consequences. He would speak of the "spare room beds" with horror, and in getting in between sheets that were so damp and cold, on beds which perhaps had not been slept in since his last visitation, and, as he expressed it--"it was like getting in between cakes of ice."

When my father heard of this he gave the bishop two flannel gowns, which ever afterwards accompanied him when traveling, and which he said "saved his life." But it was not only cold that he experienced, but sometimes too much heat. Once in winter he was shown to his room, where a base-burning stove was glowing red hot, and a feather bed was the only mattress. Before retiring he tried to open a window, but they were not only nailed down, or fastened, or protected by double windows so no air could be admitted, but the crevices had cotton glued over them. He tried to sleep, but could not, and finally told his secretary to get up, take the hair brush and break a pane in the window. He did so, and presently there was a crash of breaking glass and the bishop said: "Ah, now I can breathe"--and calmly went to sleep. In the morning the only broken pane of glass visible was in the bookcase. Such is the power of imagination even on the greatest intellects!

Arriving late one afternoon in a village where he was to preach in the evening he found his hostess in a flutter for fear that in cooking the supper for the bishop and then getting ready for church she would miss part of the service. So the bishop told her simply to put things on the table and while she was dressing he would cook his eggs himself which he did. Afterwards, in walking to the church with the rector, he listened to his hostess dilating to a crony of hers on the bishop's accomplishments--what a wonderful man he was, and ending up by saying, "And would you believe it, the critter cooked his own victuals." How few men would have shown such thoughtfulness and consideration and won the gratitude of this poor woman by helping her out of her dilemna in the way he did.

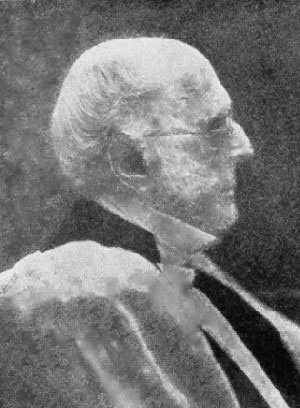

This portrait of Bishop Williams is one of about twenty taken in 1893, through the generous and thoughtful interposition of Miss Edith Kingsbury of Waterbury, who enlisted the aid of Mr. H. St. Gaudens to pose the Bishop. Miss Kingsbury gave a complete set of these photographs to the Berkeley Divinity School and they are now in the Williams Library. Posterity will be grateful to her for preserving so good a likeness of the great Bishop.

[12] Another time he met a most inquisitive Yankee who pelted him with questions as to his business, occupation, etc., and finally after the bishop had evaded his inquiries for some time the man remarked, "You must be a kind of traveling agent," and the bishop brought the interview to a close "by allowing that he was."

Bishop Williams spent many summers at Lake George and knew every foot of the surrounding country, with all its points of historic interest. He would fish on the lake much of the time and during the day wear old clothes and a soft hat that must have somewhat transformed him. He was met on one occasion by a rather pretentious tourist with his family, who were inspecting one of the old forts, and was addressed as "My man, can you tell us?" etc. To which the bishop responded by guiding them about the place and made himself so useful and interesting in describing the historic points that his tourist friend thanked him and presented him with a half dollar, which the bishop pocketed with much enjoyment of the situation. Imagine the surprise and confusion of the prelate's benefactor, when seated at dinner at the hotel that evening, to see the dining room door opened, his "guide" appear in full clerical attire, accompanied by friends, and conducted with great respect by the head waiter to his table. If the earth had yawned at that moment our tourist friend would have welcomed that method of escape to conceal his deep embarrassment.

During the Civil War a friend of Bishop Williams said to him: "You know a tax on bachelors is contemplated, and I have figured that, at your age, you will have to pay about $250 a year." "Well," says the good old bishop with a twinkle in his eye, and as quick as a flash, "it's worth it."

As I entered his library one day he was just in the act of tearing up a letter to drop in his waste basket, and seeing me, he said: "I want to read you a letter from Wilmer" and added, on seeing a look of doubt on my face of whom he was speaking. "Why, you know who I mean--the Bishop of Alabama." Then, proceeding, he explained before reading the letter that at a general convention some years previously the then Bishop of Fond du Lac Hong since dead) had proposed a resolution that no candidate for holy orders should be allowed to use tobacco [12/13] during the three years they were studying. After it was debated and defeated Bishop 'Williams asked that all mention of the matter be expunged from the record, for the reason that, if known, it might be said that the church was not in favor of temperance. This was done. Then the bishop read me the letter, as follows, viz: --

By the way, what's become of Fond du Lac and his motion? It's evident he is not "fond du Bac." What did he propose as a "quid pro quo" or rather a "pro quo Quid?"

And so the letter ran on, witty and bright, and ended in the waste basket, where, in fact, all Bishop Williams's correspondence went, greatly to the loss of succeeding generations, no doubt. I may add that he explicitly directed his executors (Rev. John Townsend and myself) to destroy every letter, sermon, etc., that we might find among his effects, but for this injunction there was slight necessity, as he had effectively attended to it himself.

We have all heard of his witty "bon mots" about the Puritans, who "when they landed fell on their knees and then on the Aborigines," and that it was always a question "whether, when the Puritans landed on Plymouth Rock, it might not have been better if Plymouth Rock had landed on them." I am told of others who claimed the authorship, but it belongs to our Bishop Williams.

Bishop Williams was thin and spare, and for so large a man he seemed to eat very little. An English bishop, calling on him, asked why he did not adopt the English dress of his rank and order--knee breeches and silk stockings. "Because,"" answered Bishop Williams, "if I did I would be arrested." "And why," asked his friend with some astonishment. "For want of means of visible support," was the quick reply. And possibly the Englishman today, if living does not appreciate the witticism.

Showing the feeling towards the Episcopal Church after the Revolution, Bishop Williams used to say it was then looked upon as one large piece of baggage left behind by the British when they evacuated this country. The bishop told me that there was a little Jew tailor in Mobile whom Bishop Wilmer employed, and one day he said his son Jakey would not believe the stories in the Old Testament, and particularly that the whale ever could have swallowed Jonah. "What shall I tell him, bishop?" the father anxiously inquired. "Oh," said Bishop Wilmer promptly, "tell him Jonah was one of the minor prophets."

In all my many years of the closest relations with Bishop Williams, only once did I see him show the least indication of temper, and that was after he had nominated a man for rector [13/14] of a large parish, whom the vestry did not elect, but asked me to request the bishop to name some one else: I did so, and he turned to me with some severity and said: "Did I not nominate Rev. Mr. -------- and the vestry refused to elect him?" To which I assented. "Very well," he said, "if the vestry does not approve of my nomination made at their request, I have no other name to suggest, and you may tell them that I said so." It was evident that he considered the action taken a reflection upon his own good judgement, after the careful consideration he must have given in making the nomination.

The frankness of his disposition is illustrated by the following incident: Many years ago when the confirmation or election of a certain bishop by the requisite number of dioceses was in doubt, a very prominent layman, interested in the outcome, knowing, though a stranger, of my intimacy with Bishop Williams, wrote me a long letter explaining the circumstances and asked me to ascertain, without mentioning his name, what the prospects were. I confess I was puzzled to know what to do, because Bishop Williams must know that I had no connection with the matter, and I did not like to use my free access to him to obtain confidential information of this character or to disclose the name of my correspondent. So I just went to him and told him the facts, without, of course mentioning from whom my inquiry came, and said he must judge whether to give me the situation or not. He appreciated my dilemma, and with the utmost kindness told me that in his judgement the election would be confirmed, but that what he said must go no further than myself and my correspondent, and his name [14/15] must not be mentioned. Thus with simplicity and directness he solved the question that bothered me and satisfied those deeply interested.

Illustrating his affection for old methods, and his dislike of changes in his administration in his later years, at one time the addition of laymen to the standing committee was agitated in the convention. Afterwards in discussing it with the bishop I asked him to tell me frankly what he desired done, if anything. "Well," said he, "I'll tell you. Just leave things as they are until I am gone and then you can do as you think test."

Many years ago we had a faithful old janitor named "Tim" at the Divinity School, who always implicitly did what he was told to do, without regard to circumstances or conditions. It happened that Miss Tibbs, who kept house for Bishop Williams wanted a glass of wine for her kitchen, and the bishop had the keys, of the sideboard and he was out. Miss Tibbs had forgotten that he was holding service in the chapel, so she directed Tim to find the bishop and get the keys. Tim walked straight into the chapel where the epistle for the day had just been read and addressed the bishop with "Please bishop, Miss Tibbs wants the keys." Without a moment's hesitation the bishop replied, "You go and tell Miss Tibbs she cannot have the keys just now," and proceeded--"the Holy Gospel is written," etc. Thus with dignity and perfect self-possession did he dispose of an astounding interruption.

As a presiding officer he was most efficient and clear. In some meeting, or convention, a man proposed some resolution so involved in its wording that its meaning was very doubtful. Bishop Williams, catching the idea, put it into words which gave its intent clearly and concisely. "Is that what you mean?" he asked, and received rather a stammering though grateful assent, to which the indignant bishop responded under his breath, "Why didn't you say so then?"

And it was also said that a like occurrence took place once in the House of Bishops, when some involved resolution was offered which the chair and house could not comprehend. Several bishops strove to elucidate it. and finally Bishop Benjamin Paddock arose and gave an explanation, asking Bishop [15/16] Williams what he thought of it, and the chair instantly replied: "That Benjamin's mess was ten times greater than the others."

No one knows better than the graduates of Berkeley how big a heart he had or how affectionately he looked upon them as part of his family. I remember one instance of a young man studying at Berkeley whose home was in the far North, and it was winter. He told the bishop that his mother was very ill, and he replied that he ought to go home and see her. The young man said he could not afford it and Bishop Williams immediately handed him .sufficient for his journey. Next day the bishop found him still at the school and asked why he had not started. After some conversation he ascertained that the student had no warm overcoat. Then the bishop handed him a check to purchase one and sent him to his mother rejoicing. No doubt this is only an example of numberless instances where his fatherly love and thoughtfulness brightened the life of many a young man worried and perplexed by financial questions.

As to what he did for Berkeley I quote from a paper read before the Church Club of Connecticut May 23, 1901, at a meeting commemorating the 200th anniversary for the propagation of the Gospel in foreign parts (pages 22-23):--

"No history of Berkeley would be complete without personal reference to our great and lamented Bishop John Williams, and his connection with the school as founder, creator, sustainer, and of his loving care as teacher. No eloquence can do him justice, or portray the noble character of the man, and rare is the life and career which has commanded more truly the loving affection and true devotion of his friends, than was his happy and deserved good fortune; and yet, with all his great gifts, his humility of character was most striking. He gave to Berkeley all he had, freely. He never received one cent of compensation, but, on the contrary, said just before his death that he had contributed from his private purse, for over forty years, at least $1,000 a year to its support and to aid the young men studying there, and at his death he left his property to help endow it. To say nothing of his incomparable teaching, guidance and influence, his money gifts must have amounted to $75,000 at the very least. It is impossible to estimate in words, or Imagination, the influence this great man has had through the length an^ breadth of the land, partly by reason of his work in the Berkeley Divinity School. Such a mind, such a personality, such a loving interest in the young men under his care, could not fail to reach far and wide, as they scattered through this great [16/17] country; and everywhere one meets those who turn with the tenderest interest to their days at Berkeley, when Bishop Williams led, taught and inspired them to work for the church.

And in conclusion let me speak a word as to the future of Berkeley. I am sure that this school, established so solidly and so long, having achieved such great results, with such a successful past, is not now to become a nonentity and a failure, nor cease to add its share of workers to the church at large. It would be a reflection on the soundness of Bishop Williams' forty-five years of work to suppose that the usefulness of the institution ended with his life. Many feared such a fate would befall St. Paul's School of Concord, when Dr. Henry A. Coit died--one of the greatest teachers ever known--but today St. Paul's stands as a living successful example that men's work lives after them. So I believe it will be with the Berkeley Divinity School. The shock was a severe one, but it has been mot and overcome, and it is the duty of the diocese to see that the great work of so grand and farsighted a man, should continue as one of the monuments of his life, his wisdom and his sagacity. He expected it to last, and made every effort to put it on a firm foundation, so that it should remain forever located as it is, which was his most ardent wish."

It gives me the most intense satisfaction and happiness to say that the expectations and hopes expressed above as to the future of the Berkeley Divinity School are being realized and that the foresight and wisdom of Bishop Williams have been justified. It has a strong faculty; it is fairly prosperous and doing a great and good work; its friends and alumni are standing by it, and it is contributing to the church a very large percentage of its most prominent and forceful leaders in the house of bishops and among the clergy.

Bishop Williams desired and planned that the Berkeley Divinity School should always remain in Middletown where he had located it. Years ago it was brought to his attention by the heirs of Edward S. Hall, who had given the original building (now called Jarvis building) to the trustees, that the intent of the donor was that the property should revert to him or his family if ever the school were removed, and that this condition had been omitted in the deed. Bishop Williams took steps to have this omission corrected by the trustees and after we had signed the necessary papers he turned to me with the remark: "That settles the future of the Divinity School. It will remain here." Other evidence of his earnest desire in this regard exists of record, and no doubt had great influence with the trustees a few years ago when the question of removal to New Haven was agitated.

[18] In 1897, when Bishop Brewster was elected assistant bishop, the Rev. Henry M. Sherman, Rev. F. W. Harriman, Hon, F. J. Kingsbury and the writer were appointed a committee to convey to Bishop Williams official notice from the convention of its choice. All met at the bishop's residence and were ushered into his bedroom and delivered our message and then Dr. Harriman asked him to give us his blessing, and, kneeling at his bedside we received it. His voice was strong and unshaken and it was most solemn and touching in its tone, as if he was taking farewell of the diocese, his work and ministrations.

We often listen to stories of the travels by buckboard and horseback of our western bishops and missionaries, and, while it is true they covered longer distances, it is also true that Bishop Williams in his visitations covered hundreds of miles in daylight and darkness, in storm and sunshine, by stage or carriage. Many old-time liverymen throughout Connecticut could tell interesting tales of these long trips and how pleased and honored they were to have so distinguished a task as safely conveying the bishop to his destination in time for his appointment. This was before the days of many railroads, of Sunday trains, of trolleys and automobiles, and many parishes were far apart, and yet combined in one Sunday's visitation, morning, afternoon and evening in succession. It seems incredible now that such a duty was performed without great weariness and injury to health, but there was never a complaint from him, in spite of his growing years.

Though many years have passed since Bishop Williams's active days, the recollections of the man linger fondly and affectionately in the hearts and memories of those who knew him. Especially in the country parishes do the people like to talk of him and of the days of his visitations (which were always red letter days in their calendar) when he took them by the hand and called them each by name, and how the eye kindles and the voice trembles as they tell of their reminiscences, and how dearly they loved him and looked upon him, as indeed he was, a father of the church and of his people.

He had, undoubtedly, an unusually strong constitution, and his capacity for work both mental and physical was marvelous. He possessed a wonderful memory and the power of concentration of mind, and while he never hesitated for a word to express his meaning, he wasted none in utterance or writing. I have often watched him work at his desk and it was marvelous how [18/19] steadily he applied himself and how his pen ran on over the paper with hardly a stop. In short, he was a master of the English language and appreciated the gift in others.

His correspondence was large, in this country and abroad, and it will never be known how many turned to him for advice and counsel. He mentioned this once to me and said many came to him who ought to have gone to their own bishop for guidance and to whom he felt obliged to refer them. It shows his enduring influence on those he taught that they should turn to him in time of trouble and need.

Speaking of his young men in the Divinity School, he said he impressed on them this simple rule, viz:--"First, have something to say; second, say it, and third, stop." Needless to say it is a rule that might embrace many other classes than the one devoted to sermon writing, and yet in modern education and composition it is a maxim rarely observed.

On one occasion I remarked that I would like to establish a chair of English literature and composition in the Divinity School had I the means, and he answered that the students were supposed to be proficient in those subjects before entering. To which I replied that it was true, but as a matter of fact few were, to which he assented fully. Would that some one in affectionate remembrance of the great founder of Berkeley, and interested in the work of the school and the efficient equipment of young men for the ministry, might be moved to endow such a professorship.

I think, perhaps, the first early communion service in Middletown was held in the room of the Jarvis building set aside as a chapel by Bishop Williams when he lived there. It was a long, narrow room, located directly over the front entrance, and there the services were held up to the time Mrs. Mutter built and gave St. Luke's Chapel to Berkeley. Well do I remember, some time in the 50 's, before I was confirmed, I drove my "two oldest sisters into town from Walnut Grove, where we were then living, to attend the early Easter service in this chapel, which. I think, was held at 6:30 the bishop himself officiating.

Christmas Day the bishop must have been very lonely after his mother's death, but he made a great deal of it, and the two following notes show how the Christmas season fully possessed him:--

December 26, 1888.

My Dear Mrs. G.--:

Let me thank you earnestly, for your beautiful holly branch. It joins Christmas cheer to the parlor, and Christmas thoughts to the soul.

The berry red, the blood outshed;

The leaves so green, the rainbow seen,

Like emeralds round the throne;

[20] The joys unseen, except in hope,

Which in the far off future ope,

Then only fully known.

With all good Christmas wishes for you all.

Most truly yours,

J. Williams.

My Dear Mrs. G.--:

Many thanks for the beautiful holly which makes my only Christmas green this year. But it is quite enough, for nothing else belongs to Christmas as it does.

I send you on the opposite page, a "Song of the Holly," which I did not write myself, though I wish I had.

With best wishes of the season for the household, I am,

Very truly yours,

J. Williams.

December 29, 1890.

The holly oh, the holly!

Green leaf and berry red,

Is the plant that thrives in winter

When all the rest are dead;

When snows are on the ground,

And the skies are grey and drear,

The holly comes at Christmas-tide,

And brings the Christmas cheer,Sing the Mistletoe, the Ivy,

And the Holly-bush, so gay,

That come to us in winter,

No summer friends are they!Give me the sturdy friendship

That will ever loyal hold.

And give me the hardy Holly

That dares the winters cold;

Oh, the roses bloom in June,

When the skies are bright and clear,

But the Holly comes at Christmas-tide,

The best time o' the year.Sing the Holly and the Ivy,

And the Merry Mistletoe,

Which comes to us in winter,

When the fields are white with snow.

The simplicity of his character needs no better illustration than is contained in his "Directions for My Executors," which I quote in part, dated in 1886:--

No. 1--I wish my burial to be as inexpensive and simple as may be: a plain pine coffin; no flowers; my body not to be arrayed in Episcopal or other robes, but in a shroud of linen; as few carriages as possible; no outer shell to coffin.

[21] No. 2. The Burial Service simply to be read by one person, to be designated by the president of the standing committee of the diocese; without any address or sermon: this I distinctly forbid: and with no additions to the Prayer Book service except a hymn after the Lesson, and the hymn to be "Rock of Ages" as it stood in the prayer book in years gone by.

No. 3. I direct my grave stones to be in form, size and material, the same as those at the grave of my mother. On the headstone nothing to be placed but my name, John Williams, and the date of my death; on the footstone my initials--J. W.

All his property he left to the Berkeley Divinity School, giving, however, the right to several of the bishops and clergy, and certain relatives and lay friends, including his executors, to select from his effects such memorials as they might choose--"an act of gracious thoughtfulness," as Bishop Doane puts it, which made us feel honored and happy that we were so affectionately remembered by so great and good a man.

I cannot close this article better than by quoting from Bishop Doane's eloquent and loving tribute to Bishop "Williams, contained in his Connecticut convention sermon in 1899:--

And now I turn from the personal associations which live in his delightful letters, and in the deep places of my memory, to speak to you about his gifts. I cannot but think that there is some strong and subtle connection between the outer and inner man: that sometimes, at least, the mould in which Almighty God casts a piece of Himself, has in it an indication of what man is meant to be and to do.

This, is quite beside what everybody knows, that there is a faint parable here of what the spiritual man is to be when the soul shall clothe itself with its own body to suit its own capacities, for their untrammelled expression in the day of regeneration. There is a strong suggestion of this in the way in which in almost all men, the spiritual nature fashions and illumines, the outer man, until it speaks its strong emotions in the transfigured face.

And no one could see the gift of natural manhood of Bishop Williams without the sense of dignity, and power and will, and intellect, that were stamped upon it. He was a spiritual prince, from the great dome of his head in every lineament of his face, his keen eye, his firm lips, his strong chin, his over-arching brow, his finely moulded nose, his commanding presence, his firm tread.

He was a man men turned to look at and stayed to look up to, not for his height in inches, but for the exaltation of his bearing.

The exquisite tribute of Bishop Doane to our great Bishop Williams leaves but little for the pen of a layman, but it is hard to resist the utterances of the heart on such a theme, even though it may savor of repetition.

Of all men I ever knew, he possessed most fully that divine gift of charity. Nothing except deliberate wrong, personal, corporate or political, moved him to sarcastic or strong denunciation. Considerate and patient of all, he was an embodiment of truth and equity. In parish disputes brought to him for adjudication he listened to clergy and laity, and counseled both [21/22] fairly. He was so great that no prejudice blinded him, and he stood, as it were, upon a mountain height, towering head and shoulders above his surroundings, and settling the troubles of his people with courage, and justice to all. Sometimes I fear we did not appreciate him in this respect as we ought to have done.

As the long line of clergy followed him to his burial I could not but notice how large a majority had listened to his teachings and been subject to his fatherly training and interest. And through them let us hope that the impress of his great mind and character may pass to future generations.

No greater memorial could he leave than the work that he has accomplished in training men for the ministry. Those who have been under him will appreciate this, and not only was he their teacher but their friend and counsellor, without whom many would have turned aside to other vocations. No one will ever know his benefactions, for like the dew from heaven, they came silently and passed into oblivion when the night of trouble ended.

At his bier stood Roman Catholics and all Protestant creeds--mourning alike the irreparable loss. The bells of other churches tolled his requiem in union with ours, and both in life and death all men loved and honored him.

One marked evidence of a great mind was his, and that was his attention to detail. To the very last he retained this, and seemed loth to surrender to others the duties he had so long performed. His memory was marvelous, and the tenderness of his heart and consideration for others abounded in his sick chamber as strongly as when in health. Only a few weeks before his death he dictated and signed a note of encouragement and sympathy to a little boy who for many weeks had been critically ill. He took a strong interest in public affairs, and not long before his death, and with impressive utterance, he said to me: "From the time we enter on foreign conquest, and depart from the traditions of our fathers, from that date you may mark the downfall of the republic."

He was indeed a great man, endowed with splendid gifts of heart and intellect, a wise counsellor, a just judge, who as a churchman was preeminent, but who as a statesman, Jurist, or in any other profession or walk of life would have been a leader and master. Simple, humble-minded, straightforward, strong what an example for us all.