|

THE BISHOP POTTER MEMORIAL AT MONT ALTO, PENNSYLVANIA HONORARY CANON, CATHEDRAL OF ST. JOHN THE DIVINE, NEW YORK ________ BISHOP OF HARRISBURG AND THE ARCHDEACONRY |

I AM grateful for the honor of Bishop Darlington's invitation to take part in this Service. In the words that I desire to present to you in memory of Henry Codman Potter, the Church work at Mont Alto in the early days, as recalled by his biographer, ought to have the first place.

In the summer of 1856, our friend (whose father was then Bishop of Pennsylvania) served as a lay-reader. "The iron works nearby had been set up, and the owner had given an acre of land for a church. This had been consecrated in 1854.

"The lay-reader took the superintendence of the Sunday School, organized a choir, [1/2] and began cottage lectures in the outlying farmhouses, where he preached his own sermons. A log-house in the yard of one of his parishioners contained his study and bedroom."

I love to think that here, even before his ordination, Dr. Potter began to be a preacher of righteousness, and I trust that the work for the spread of light and truth which he inaugurated in this Chapel is like Joseph's fruitful bough of old time, even a fruitful bough by a well whose branches run over the wall. Surely that work is more than ever full of happy promise now that the State School of Forestry is established close to this consecrated ground.

My acquaintance with Dr. Potter began in 1879 and continued to the close of his life in the summer of 1908.

While his assistant at Grace Church, New York, I learned to admire him as an ideal Rector. It was a memorable period in the life of that parish. As soon as plans for any material improvement, however costly, were approved, funds were forthcoming on the run. It seemed sometimes that all the Rector had to do was to touch a button so that a ready power house might [2/3] do the rest. And whatever the facility which brought about such prompt results, the simple truth is that the hearts of the people were as ready as any power house for active service. The Rector and his Vestry were brethren dwelling together in unity. A discordant note among them was unthinkable. The religious Services were worthy of the spirit of worship. The congregation was sometimes called "fashionable." It certainly had the fashion of giving a liberal support to Domestic and Foreign Missions and maintaining such works of mercy as a Day Nursery and a Fresh Air Fund. And one of the secrets of all this was the fact that the preacher, house-to-house pastor, organizer and director were all alive and alert in the one gracious and masterful mind that "felt at each thread and lived along the line" of every part of the work from its centre to its circumference. After his death a marble bust of Dr. Potter was set up in the North Transept of the Church.

Grace Chapel was a spacious edifice where, in addition to Services in English, it housed for a time a German Mission and an [3/4] Italian Mission. Over a thousand children were enrolled in its Sunday School.

In the pulpit and out of it, Dr. Potter was a herald of life's true way, and his Gospel message had no uncertain meaning, whether it sounded out in "kindling thought and glowing word" or found expression in his daily conduct. Set by the Church in high places of honor, he set himself in them to serve his fellowmen with the Saviour's love. He had compassion on the multitude, and his sympathy was a fountain of good cheer. He made a special study of the problems of Capital and Labor, and read books of experts on the subject. He could without prejudice hear what the capitalist had to say, and he responded to requests of laborers to act as arbiter in their disagreements with their employers.

And what a winning tact was his! Many words may not define tact, but any one was close to its meaning when close to Dr. Potter. It is said of some paragon of politeness that it is sweeter to get a refusal of a loan of money from him than to get the money itself from the hand of another. I have sometimes thought of that when I have seen Dr. Potter rid his office of a tiresome [4/5] visitor. And the marvel of it was that the courtesy of the action was so delicate that it seemed to please the visitor to be bowed out before he was ready to go.

One of the distinctions of Dr. Potter's career was his genius for work. His energy was apparently as constant as his heartbeat, and always suggested a reserve of power ready for any claim upon it. Buoyed with some inward force he seemed to feel "a pinion lifting every limb." His mental faculties, like the muscles of an athlete, were so sound and well trained that they seemed to work together with alacrity.

The spire of Grace Church is a monument to his constitutional antipathy to shams. In the old days few admirers of the Church's Gothic beauty knew that its stately spire was only a wooden imitation of stone. In due time, however, Dr. Potter raised a fund for a real stone substitute. And then, in his absence from the city, a mistake was made. An expert connected with the oversight of the improvement gave an order to a painter to try to make the new stone look like the old. The stain had progressed downward twenty feet from the top, when it was removed. And now it was left to [5/6] Time to do its own staining, which, by the way, is not usually a long process in a city atmosphere.

It is well known that Bishop Horatio Potter was the founder of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in the sense that he appointed a Committee of fifteen to consider a proposed Charter. The Charter of Incorporation in 1873 named the first Board of Trustees. At the first meeting of the Board in the same year a committee was appointed to consider and report on the question of a site, with the understanding that the choice must fall on ground below Central Park, and three of the trustees subscribed $100,000 each for preliminary expenses. However, a financial panic a little later was a blessing in disguise so far as the proposed cathedral was concerned, for it struck two of the generous subscribers, and their pledges went down in the wreck. And that meant a Cathedral on the highest ground in Manhattan. There was no other meeting of the trustees at which there was a quorum until Henry C. Potter had been consecrated as Assistant Bishop, and had received full charge of the Diocese on account of his uncle's age and infirmity. In [6/7] 1886 they were again called together. In 1887 a site was chosen on Morningside Heights, afterwards designated by the Board of Aldermen as the Cathedral Heights, and a systematic campaign, inaugurated in the preceding year, was carried forward with redoubled activity to realize on solid ground the great enterprise proposed on paper. And thus the farseeing uncle gave to the Cathedral its name and its chartered right to live, and the no less farseeing nephew then gave to the Cathedral its local habitation and the beginnings of its visible growth. The cornerstone was laid by Bishop Henry C. Potter in 1892. Not long afterwards the Crypt was in readiness for services, which were attended by large congregations. In 1904 the interior of old Synod House was remodeled to provide a suitable hall for the Diocesan Convention, and the Convention met there in that year for the first time in the Cathedral Close. The occasion was made memorable also by the presence of the Most Reverend Dr. Davidson, the first Archbishop of Canterbury to honor our land with a visit. Bishop Greer completed and consecrated the Choir in 1911 and then laid the foundation of the [7/8] Nave. His Memorial at the Cathedral will be the Chapter House.

After the death of Bishop Greer and Bishop Burch, Bishop Manning in 1921 succeeded to the task of completing the third largest Cathedral in the world. He quickly proved his eminent fitness to make a wise use of his splendid opportunity. Under his inspiring leadership the Nave has climbed to the top of its towering height and the roof is already beginning to cover it.

One of the contractors has expressed the opinion that this work of wonder has progressed twice as fast as he had expected. But we see Bishop Manning in that. It certainly shows his touch. Whatever comes under his master hand naturally breaks the highest of ordinary records of progress.

If any other diocese wants a cathedral, it could hardly do better than to consult him, if only to catch the glow of his zeal, which no languor knows.

In the early part of his Episcopate, Dr. Potter began the practice of introducing his newly ordained deacons to the "destitute, homeless and forgotten of their fellowmen" on Blackwell's Island, now named Welfare Island. After their ordination on Trinity [8/9] Sunday morning, he accompanied them a few hours later to that island, to be present at the Chapel of the Good Shepherd (the gift of a former Grace Church parishioner), to take part in the service of confirmation of candidates from the Alms House, now called the City Home. And that practice has continued ever since.

In a city so polyglot as metropolitan New York, it was not strange that the Bishop had much to do in directing the plan that provided for the seven Chapels of Tongues that are now grouped about the Sanctuary. It seems fitting, therefore, that St. James's Chapel, one of the largest and most beautiful of these Gothic shrines, should become a memorial to him, through the action of the Messrs. Clark, on behalf of their mother, Mrs. Potter. In this Chapel stands Fraser's masterpiece of a recumbent figure of the Bishop, surmounting the sarcophagus erected by the Bishop's children.

The great marble Pulpit of the Cathedral was another of his memorials, presented by a friend from Troy.

The Bracony marble bust of the Bishop was presented by a few of his friends in New York.

[10] One of the massive pillars of the Choir Sanctuary was set up by the Bishop in memory of his father.

In the Ambulatory just back of the Altar is the Founder's Tomb. It represents the labor of love of a Special Committee of which Dr. Manning was Chairman. It is surmounted by a recumbent figure of Bishop Horatio Potter, and faced with five richly carved figures, including a figure of St. John the Divine.

Meantime, under Dr. Potter's administration, the Pro-Cathedral in Stanton Street, in a neighborhood abounding in tenements, was opened for services, and until its transfer to the City Mission Society some years later he raised the funds required for its current expenses. It became more and more a centre of benign usefulness in that populous neighborhood. Three of its Vicars became Missionary Bishops.

The Pro-Cathedral attracted a little additional attention on one occasion by the ordination of the Rev. Dr. Briggs, a professor in the Union Theological Seminary. He had become a candidate for Holy Orders, but when it was announced that he was to be ordained at the Pro-Cathedral, threats [10/11] were published that a solemn protest was to be made at the Service. We were all wondering, therefore, what kind of a scene was in store for the occasion. When the Bishop at the beginning of the Service read the sentence asking anyone to come forth and make his declaration if he knew of any impediment for which the candidate ought not to be ordained, he made what might well be called an eloquent pause. The moment seemed tense with ominous silence. And now, if any bishop ever looked really majestic without a mitre, it was this fine figure of a man standing there in the robes of his high office, with serenity throned on his brow, waiting for that threatened protest's puny thunderbolt. Suddenly from the worshippers a faint sigh of relief seemed to rise and steal away as the Bishop's voice broke the spell by resuming the Service.

At another time the Pro-Cathedral found itself famous as a real storm centre. Its environment had become a more than ordinary menace to its families, on account of political corruption that permitted vice to be rampant in the streets. The appeals of the Vicar for protection seemed to be of no avail. Finally the Bishop wrote his memorable [11/12] letter to Mayor Van Wyck. It was nothing less than a classic. A more scathing denunciation of the lawlessness of officials sworn to uphold the law, could scarcely be found. At any rate, it seemed to shake the city out of its lethargy, and it rang in as with a fire alarm a reform administration, at least for a time.

As it was my privilege to act as the Bishop's secretary throughout the twenty-five years of his Episcopate, it can well be understood that I learned more and more to appreciate the forces of character that explained his achievements and added them to the shining annals of the Church. During all that time I was present at the sessions of the House of Bishops, as it was my duty to keep a record of each day's proceedings, and this gave me opportunities to hear him in his share of the debates of that House as well as to see the quality of his work as a member of important committees. When he rose to speak he won quick attention without the aid of the Chairman's gavel. He never hesitated for a word any more than an arrow hesitates on its way to its target. He was what is called a fluent speaker. Now it may be possible to find in [12/13] some one's fluency of utterance a reminder that language was invented to conceal thought. But such a witticism could never apply to the choice diction that fell in smoothness and richness of tone from Bishop Potter's lips. When he spoke he had ideas to express, and he expressed them so aptly that they left a clear-cut impression on the mind of every hearer.

The grace and dignity of his manner were as much an inseparable part of him as the manly impressiveness of his form and features. He was so human that nothing human failed to interest him, and none knew better than he that the most interesting of humanity's claims is the image of the divinity that makes all men brothers.

Of the many endowments that graced his mind none was of a higher order than the gift of prayer. It was an uplift of the heart to hear him pray without set forms at family worship or in the house of mourning. It was a son's soulful voice pleading on bended knees for a blessing, and the air seemed to fill with the presence of the Father.

It may well be believed that the Bishop had a voluminous correspondence. It was [13/14] a rule of his to answer all letters promptly, whether any of them came from persons who had any claim upon him or from strangers who mistook him for a fairy godfather.

One day he received a letter from a woman in another diocese, who said she had just completed a crazy quilt, and she asked him to be good enough to sell it to one of his rich friends as he could probably get more for it than anyone she knew would be willing to pay.

Another letter was from another stranger saying that he was in Brooklyn visiting some friends who were poor like himself. Then he went on to express the hope to be invited to dine with some multi-millionaire, in order to see the inside of the palatial home and the social manners of the family. Would the Bishop kindly arrange accordingly?

Before Prohibition made its mark on the Constitution, the Church Temperance Society, with which Bishop Potter was for a time identified, had a dual basis of membership, namely, total abstinence and a moderate use of alcoholic beverages. And even at that time there was no lack of adverse criticism directed against persons in high places, [14/15] in or out of the Church, who were not prepared to pledge themselves to total abstinence.

On the Bishop's return one day from a visitation up the Hudson, he entertained me with an account of his experience with a boatman. It was a stormy night. The river was unusually rough. The boatman was reluctant to row across to enable the Bishop to make connection with a train on the other side. Finally, however, the oars were creaking in strong hands, and after the other shore had been reached the Bishop and his companion landed just in time to see the headlight of a locomotive moving away from the station. This was a keen disappointment. None the less, "E'en in that dire extreme of ill, Ulysses was Ulysses still," that is to say, the Bishop's sense of humor did not desert him, but functioned true to its traditions as a life saver. He turned to the boatman with the question: "Well, what can a layman say to express a cleric's sentiments at such a moment?" And the boatman, who was a teetotaler with the courage of his convictions, and had heard that the Bishop was a friend of publicans and sinners, [15/16] said: "Oh, no, Bishop, please excuse me! How can I say a really fitting word to help anyone who has such views as yours on the temperance question?"

In spite of a Bishop's right to laugh now and then, and to help others to laugh, faces have been known to take on a look of surprise, if not of horror, when a Bishop has presumed to exercise the grace of humor. I heard a Presiding Bishop of the Church tell of his own experience in giving a strong hint, by means of a bit of mock seriousness. He was a guest one winter night in a rural parish. "What are the duties of the Chaplain you have with you?" asked the host. In a stage whisper the Bishop replied: "Let me tell you a secret. As you know, I am getting on in years. You can guess my life current is none too warm. Well, when I go away from home for a night, this Chaplain goes with me. As you see, the hue of youthful health is on his cheeks. But young as he is, he is known for his sound learning and efficiency. He is my bedwarmer. It is his duty to lie in my bed for an hour before it is time for me to get into it, and during that hour he absorbs the spare bedroom dampness of the sheets!" We can imagine the relief [16/17] of the startled listener when he was assured that the strange thing he had just heard was only a little fireside pleasantry. Anyhow, it was evident that the author of that pleasantry had a care to avoid the dread error of Lord Bacon who succumbed, not to a fall from high honor, but to chill sheets in a friend's house.

How grateful a Bishop must be to the safety valve of humor when his optimism under difficulties threatens to blow up! Think what it means to have the care of all the churches, in addition to the care of everybody willing to give him something extra to think about!

Dr. Potter literally heeded the scriptural injunction to be given to hospitality. He was fond of welcoming the clergy and laity to entertainments at his home. When presenting candidates for confirmation his clergy addressed him of course as Reverend Father in God, but at all times they thought of him with filial affection, and knew that he regarded them with fatherly interest in their welfare.

He was particularly thoughtful in sending holiday gifts to clergymen who were on duty in lonely mission fields on meagre salaries. [17/18] If he thought some new book ought to be in the hands of the clergy, he ordered hundreds of copies of it to be distributed among them.

He was especially glad to arrange some cheering surprises for them. I recall such an occasion with grateful interest. A clergyman up the Hudson had made a rare record of fifty years of continuous service as Rector of his parish. The Bishop asked me to arrange, in his name, for a dinner at the Metropolitan Club for a goodly number of more or less elderly presbyters of the Diocese, but first of all to get the promise of the Rector that he would be present at the chosen time. Besides I was cautioned to avoid letting the Rector know that he was a guest of honor. Well, the banquet was of course a bright one, and when at its close a golden cup was brought in and set before the Bishop, he began his address. I was sorry for the Rector, who could not guess what was coming, and therefore could not help being overwhelmed when he heard his name mentioned with praise and found the cup tendered to him by his beaming host.

And now I fancied the hour had come for handshaking and parting, but suddenly a [18/19] big silver vase was set before the Bishop. And then--well, the surprise of my life closed over me. However, the Bishop's kind words revived me. I was feebly able to thank him and carry off the vase.

Bishop Potter seemed to have an intuitive comprehension of the value of the claims that thronged into his notice. The law of proportion ruled in his choice of the use of the passing hours. The things that ought to wait were made to wait for the things that had the right of way.

His authorship of books, Yale and other lectures, presidency of The Century Association and The Pilgrims' Society, and after dinner speeches, were apples of gold in pictures of silver, but they never crowded out any Church work.

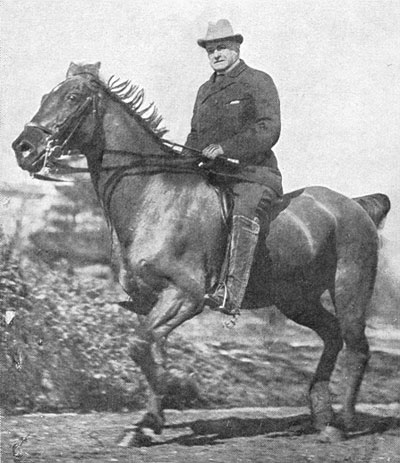

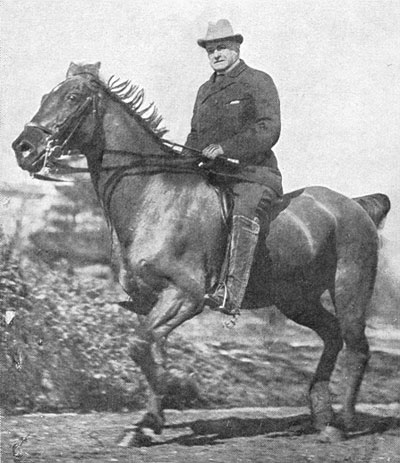

His early morning ride on a spirited horse in the Park was not prompted merely by a taste for diversion, but by a will to keep himself fit for the pressure of exacting duties. Like the youthful old gentleman in one of Lord Lytton's books, he found out what agreed with him, and adhered to it like clock work.

Order is heaven's first law, and it was his. No one could know him without seeing [19/20] that he allowed nothing under his control to escape the rule of his orderly method.

I have never seen on any man's desk a more beautiful example of the dress parade of perfect order than I have seen on his desk on any day of the year. No book or paper was allowed to lie there at an acute angle. It must lie there foursquare or not at all.

He seemed to know just where any book was to be found in any part of his library. More than once I have received from abroad the key to his desk with a description of the drawer or pigeonhole where some important document was to be found.

And this token of the orderliness that ruled the day kept on and into the night.

Alas, how many there are who fail to keep step with the procession of the world's work simply because something is the matter with their sleep! When Dr. Potter has told me of the normal sleep with which he was invariably favored, I could well understand the daily freshness of his strength.

He was immune from the poison sting of insomnia. When his eyelids closed on his pillow at any hour of the night, it was not [20/21] to give his mind a chance to roam backward or forward in restive wakefulness. With that closing of the eyelids sleep responded at once to the signal, and took hold of him with a grip that allowed no interruption, and then it set to work with its knitting, and kept at it until "the ravel'd sleeve of care" was made whole again for any further wear and tear that might be coming on the wings of the morning. Well does the Psalmist remind us that God giveth His beloved sleep. Such sleep is so precious that for it many an uneasy head that wears a crown might be willing to lay down its crown.

And now sleeps well indeed the one time Lay Reader of this Memorial Chapel whose full and noble life has meant so much to the forward movement of pilgrims on the King's Highway, for he is fallen on the sleep that is too deep for the day.

Before that sleep dropped the curtain of finality upon his busy career it was always good to note the rare charm of his poise. It was a mystic balance wheel in his spirit to guard the even tenor of his thought and demeanor, and it was never known to nod at its post. It seemed as if that one characteristic were enough to identify him anywhere [21/22] and at any time, for to him to have any breath meant to have the breath of that poise.

Nor could anything shake his loyalty to his ideal to do justly, and love mercy and walk humbly with God. That ideal was not a mere picture on a wall like a collector's prize possession. It was a picture possessing its owner and breathing with power from on high. Its full meaning could be known only when it thrilled into action in the service of God. If any man will do his will he shall know of the doctrine.

Bishop Potter's treasure was his work and there was his heart. For him to live was Christ and to die was gain. As a leader in the Church or in citizenship, he was a living epistle of a Christian gentleman that any one could read. He was always a man of vision but never a visionary. He could watch a bow of promise on a rain cloud and watch his step at the same time. In helping others to be hopeful, he helped them also to be practical. His eyes, like those of other intelligent human beings, were open to the world's charms, but he was an exemplar of the manhood that is free from the spell of the world's snares.

[23] He was a sower of the Gospel of redeeming hope in the wills and affections of sinful humanity, and made full proof of his Ministry because his was the faith without which it is impossible to please God, and with which His little ones go forth as the mighty. Such a sower's work may at last seem done, but it never is. It keeps on its way in season and out of season, and all along that way it is found in victories of the faith and in flowering fruits of the Spirit.

As fast as coming years are come, they make use of that goodly heritage and are better for it. For anyone who has a place in the sun or a hope of it, the question of every hour is: What hast thou that thou didst not receive from the passing day or from the centuries that are past? And wisdom seems to say to those who may be tempted to boast of the might of their power: Other men laboured and ye are entered into their labours. It can never be otherwise while human life is on the earth with the manifold tokens of its dependence upon the mercies that mark every step of its way through the world.

And so the memory of the just is blessed.