A FAMILIAR criticism of the French nation is that their language does not contain the word "home." "Home, sweet home," cannot be translated into French, because the corresponding French word is lacking. It would be an interesting quest for the student or the statesman to determine how far this lack of the home idea is responsible for the many social and political evils which have placed France in a state of decline without any prospect of adequate remedy. The same question confronts the American people of to-day, and there is no social problem before us, I think, which begins to equal it in immediate importance.

The home is the actual foundation of the nation; the bed-rock upon which the national structure rests; the only basis from which the national strength can be calculated. It is the only school of purity and of patriotism. If the moral character of men and of women is not molded during their plastic period, youth, it is more than likely that it will never be properly molded at any time. Love of country is love of the fatherland, love of the home-land--merely love of the home expanded until it embraces the land which contains the home. "Every man will fight for his home," said one of our orators; "but no man ever yet shouldered a musket for his boarding-house." This is a picturesque way of stating the fact, but none the less it expresses a deep social principle.

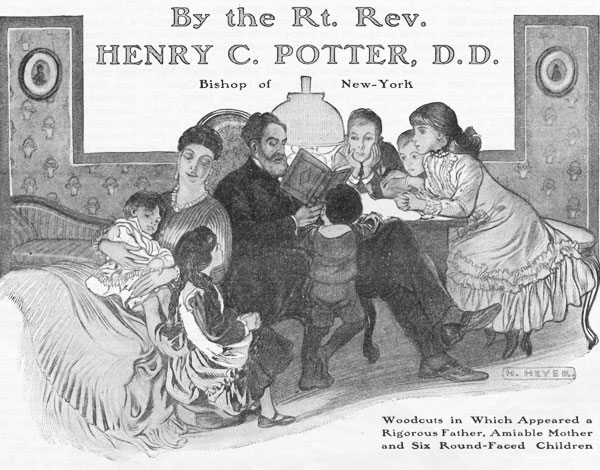

That the home, with us as a people, is steadily upon the decline, is unfortunately a fact beyond denial. Those gentle domestic interiors which were frequently to be met with in the magazines and the picture-shops of the last generation, woodcuts in which appeared an exceedingly rigorous father, an excessively amiable mother and six round-faced children--varying in size and age, but otherwise as alike as postage-stamps--we no longer see.

The question is, Why have they disappeared? The family were always grouped about a lamp, and the father was always reading from a book, inferentially a most excellent book. Is it that gaslight, replacing the lamp, has destroyed the family circle? Is it that the father no longer has time to read? Is it that the six children, cleverly disposed wherever there was room for one in the picture, represent families of a size which have now become so rare that they are to be found only among our foreign population in the tenements? Is it that our young people are now more willing to instruct their parents than to be instructed; more willing to give than to receive? Has the undoubtedly good book been so far replaced by destructive criticism that the father, hurrying home from Wall Street to read to his family, would not be able to find one? These woodcuts were artistically crude; but they served. They met a popular demand, or they would not have been so numerously drawn and printed. Does the abler artist of to-day find no inspiration in the home circle as a subject, because the people are no longer interested in the home?

I am afraid that all these questions must be answered generally in the affirmative. All the conditions of life in this country today clash with the old home ideal. The primary cause is to be found in that republican form of government which opens every avenue of success to all; which develops the individual imagination among men and women far more rapidly than it develops the capacity of each to attain the success desired. The financial pressure, the rush for wealth, leaves the father little or no time to think of his family. The social pressure, the custom among her kind, places so many responsibilities upon the mother outside of her home that she has not sufficient time to properly meet the responsibilities within. There is no doubt too that, lacking the old kind of home, we are not making the old kind of mothers. That marriage is being viewed in a more and more flippant way by young people is only too evident. That the American woman is tending toward shallowness of nature; toward an increasing absorption in herself, as against that altruistic devotion which is at once the natural destiny and divinity of the sex--is only too true. Noble-minded women are ever trying by lecture and essay to lead their sisterhood out of the wilderness; but the tendency does not change. The question is, What are those who love their country and their kind to do in this matter of building up the home?

The only answer is the education of public opinion. And it is a matter upon which we may congratulate ourselves that the difficulty is no worse than it is; that the evil has not yet, as in France, passed beyond the limit of practical remedy.

One of the most valuable and most admirable qualities of the American people is their quickness of apprehension. Interest in ourselves, interest in our own welfare, has become an eager individual quality under our republican training. As individuals we rarely need to be told twice what course of action is best for our future well-being. And since the value of the home influence is so clearly demonstrable and so entirely undeniable; since the home is the surest basis and storage warehouse of potential happiness, all those who desire and who are seeking the rehabilitation of the American home have truth upon their side; have the strengthening consciousness in their endeavor that truth is mighty and must prevail.

One certain fact is that the ideal still exists among us as a people, and exists in full strength. Much of the enormous and novel popularity of our President is due, I am convinced, to his really ideal quality as the head of his family and his home, his constant championship of the home interest. In the photographs of himself and his family the old and forgotten pictures to which I referred have come back to us. The undoubted popularity of these pictures proves the strength of their popular appeal; proves that the home ideal still animates the popular heart or it would not so warmly respond to the photographic stimulus. His emphatic pronouncement against "race suicide"; his enthusiastic indorsement of "The Simple Life," have been perhaps the most vigorous educational efforts of the kind I refer to which have yet developed. How much good they have accomplished there is no means of determining, but there is no doubt that they have been of great value to the nation. It is possible that the President might actually do more good to the United States by strenuous endeavor in this educational direction than will ever accrue to us from the Peace of Portsmouth or the Panama Canal.

All persons who have read the first chapter of the life of Phillips Brooks know how a noble mother, an upright father and a perfect home can train boys into noble men for the service of their country and their God. Few, however, need to be told this. They freely admit it as a rule; but the woman is inclined to say: "I am unfortunately not a noble or broad-minded woman"; and the man will say: "That's all right, but it's about all I can do to pay the bills."

The answer to the woman is that motherhood is essentially noble; that mother love is the noblest, most exalted emotion that animates humanity; that, the impulse being in her, a little thought and study will reveal its opportunity. The man should understand that in these growing children lies a capital of happiness so much more important to his later life than any other capital which he may accumulate than the latter is practically negligible; that in their respect, their sympathy, their love, all of which are to be won in their childhood and in their home circle, lies the only real and rich happiness which can come to him in the second half of his mundane period; that, in other words, as the pursuit of happiness is the dominant law of human life, the only possibility of happiness in the last half of any life lies in children, and in children who have been loved and cared for in their youth.

What does life offer to any man or woman after forty-five? With the woman her beauty has begun to fail, old age confronts her, a new generation of fresh-faced beauties has long since pushed her to the wall in the social assembly, and that disillusion which is the inevitable harvest of the years has stripped the glamour from all the things which interested her. Think of the happiness of the woman of forty-five whose interest in life and hold upon affairs are made intenser and stronger than ever through her children, as compared with the woman who, equally disillusioned and without children, has nothing left to struggle for, nothing to interest her, nothing to animate her, to give color to her cheek and light to her eye, nothing but loveless solitude and burdening despair! Think of the warmth of love which surrounds the one; the chill of isolation which envelops the other!

With the man, up to forty-five, the struggle is all-sufficient. If he is a strong man, he loves the game of wealth, and may be pardoned if, from his marriage to the zenith of his life, he devotes most of his time and thought to playing it. But what of him when his own disillusion comes, as come it must? What of him when he learns the lesson that beyond the small limit of his necessities money has no actual value? that the greatest value in all things human, based upon the pursuit of happiness, is love? To him, as to the woman, interest in life, love of life, rejuvenation and long years lie in the possession of children. That no man or woman can live out life practically and successfully without children, is a text which cannot be too widely preached.

None the less, many fear. They fear that the children may not turnout well, may be, instead of an added blessing, an added burden and a source of sharpest pain. So they probably will be if neglected. The harvest of love is open to all; but it is like any other harvest. It must be watched, tended and cherished, if the harvester is to have his reward. The law of life as we must meet it is simple. Without children, its value ceases largely with most people at forty-five: including children--they are the greatest of all blessings in the later years, but they must be treasured and appreciated in their earliest years if the blessings are to be garnered.

These principles apply with equal force to our limited wealthy class and to that immense middle class, financially speaking, which constitutes the mass of the commonwealth in all countries. The poor, upon whom the social superincumbent pressure falls heaviest, and who are least able to sustain it, do and must do as best they can. But it is one of the finest and most splendid facts in human nature that in the poorest homes we frequently find the most ardent love for children, the most eager interest in their life success, and the most painful sacrifice of comforts in order that the little ones may be properly fed, clothed and, what is most important, educated.

It is the children of the rich who suffer most. An English caricaturist once drew a picture in which an elegantly dressed woman of fashion stood staring at a little girl in Kensington Gardens. "That child looks very much like my Flossie," she said to her friend. And then, to the nurse: "I beg your pardon, but aren't you my nurse?" The nurse deferentially asked her name, and was properly pleased to meet her mistress for the first time.

This is an extreme statement of the case, but not so extreme as one might suppose. We are much better off in this country in this respect, in so far as our dominant social stratum is concerned, than are the English. None the less, there are many a boy and girl to be seen in Central Park whose only really intimate companions are the governess and the groom; and it is not from governess or groom that the sweet sanctities of the home life are to be learned, that the elements of a strong and noble character are to be obtained, that the preparation for the struggle of life, for the struggle against oneself, as well as against the ever-present temptations that lead to destruction on every side, is to be received.

One of the most excellent scenes which have come from Mr. Kipling's pen lies in "Captains Courageous." Here is an American father, Mr. Cheyne, a multi-millionaire, the lord of many railways, steamship lines and factories, who like many another rich man has had no time in which to get acquainted with his son, a boy of fourteen or fifteen. The son, until he fell overboard from an ocean steamer and was rescued by a Gloucester fishing-boat, was the shallow, spoiled, selfish and rude youngster with which we are only too well acquainted. He had been entirely left to the care of a weak and shallow mother, with the usual result. Many months of hard work under the democratic rule of a New-England fishing boat made him into something else; woke into active being that manliness which he inherited from his father; those great and grand impulses which we can proudly say are essentially American, and which have made our country what it is. The scene I speak of is that in which, after the missing son has been found, after the lesson has been learned, after the dead life with its dead millions in a childless home has been awakened to new and vivid beauty by the finding of the lost one--the scene following this in which the father sits down to really get acquainted with his son.

I do not think any man can read this without a quickening of his pulses; there are few fathers who can read it without tears coming to their eyes. The tragedy is so great and so clear: a boy of splendid possibilities so neglected by his father and mother that the only possible future before him was the selfish, idle, worthless manhood which parental neglect had forced upon him. Providence, through the rough hand of a weather beaten Yankee fishing-captain, had wrought the wondrous transformation. How deeply this truly American millionaire felt, how great was his unspoken gratitude to that fisherman, how warm and deep and tender was the love in his heart for his precious son, ruined by his money-getting neglect and saved as by a miracle, the reader feels, and it would be well if all men could read and feel it, whether they have sons or not.

In the same line of development is, the true story of an eminent Wall Street financier who said: "Friends? All the friends I have on earth are under my own roof." He expressed a fact which some other men realize keenly. But with all his wonderful genius as a financier he was a man who loved his family and loved to be with his children, and richer than any other reward which life brought him was the love and sympathy of his home circle.

The home of any man or woman, boy or girl, is the one and only place on earth that is characterized by a community of interests. It, is the one and only scene of mutual service and mutual sacrifice, the only place where the personal touch, born of affection and educated by experience, can play its part in the formation of character. Yet home life, in New-York at least, is coming to be a shrunken and shriveled thing.

Love alone can constitute the home as it should be. It is not that our mothers and fathers lack love for their children; the evil it is that the financial and social pressure of modern American life leave them no time to express that love in the careful consideration which childhood demands. But this can be met by the education of public opinion, and I believe fully met. I believe that the clergymen of all denominations can find no more valuable precept to impress than the value, the need, the honor and the glory of the home circle. I believe that the editors of daily newspapers in preaching the precept, the editors of weeklies and magazines in explaining the practice, can do the widest possible national good in building up the "Home Useful", as well as the "Home Beautiful." Not only good men come from good homes, but good citizens as well--citizens as alive to the municipal as to the national need.

The only solution of the marriage question will be found in the quality, the education, the preparation, of those who marry, and this preparation can be given only in the home. Let it be remembered in our school systems, lower and higher, that no education is good which does not make men more manly and women more womanly. Architecture and the modern apartment-house are against the propaganda; they are not homes, and they never will be. But their reign will be temporary, since suburban railways and the love of open air and comfort must eventually surround all our large cities with homes as of yore. The rush to the cities is a great and antagonistic evil; but this must correct itself in time, as do all erratic social movements. Let all who realize the priceless value of the home and home influence become their propagandists. Any man whose desire is to make humanity wiser, better or happier will always find humanity ready to assist him.