I. SPADEWORK ON AMERICAN SOIL

ON Advent Sunday, November the 28th, 1847, the Parish of the Advent, Boston, held its first service in a new place of worship—a remodeled meeting-house situated on Green Street. The officiant at that service was the Reverend William Croswell. Among the worshippers in the congregation that day was a young man seventeen years of age. He was Charles Chapman Grafton. Two years later the staff of the Advent was augmented by the acquisition of a young priest from North Carolina, the Reverend Oliver Sherman Prescott, who came as an assistant. It was these two men—Croswell and Prescott—who exerted a profound influence upon the life of Charles Grafton.

On the Fourth Sunday after Easter, May the 15th, 1851, Grafton lined up with the other members of the Confirmation Class of the Church of the Advent and marched with them to Saint Stephen’s Chapel to receive the Laying on of Hands. The reason for this unusual procedure was the fact that the Diocesan, the Rt. Rev. Manton Eastburn, had refused to visit the Church of the Advent. During a Confirmation Service which he held at the Advent in 1845, when the Church was located on the corner of Lowell and Causeway Streets, the Bishop had been highly displeased with, certain features of the services. We read in A Sketch of the History of the Parish of the Advent in the City of Boston, 1844-1894:

“The bishop’s main objections to the service related to the use of the word ‘Saint’ except as applied to the apostles, to the fact that the clergy knelt with their faces to the altar instead of kneeling into their chairs, and to certain other things which appeared to him to savor of superstition.”

Henceforth the Bishop refused to visit the Parish until alterations were made in the arrangement of the Church and in the mode of conducting divine service, and in consequence, each year, the Confirmation Class of the Parish of the Advent was confirmed in some other church.

[2] The episcopal boycott of the Advent was, unhappily not the sole travail with which that Parish was visited. In the autumn of 1850 a presentment was served upon Oliver Prescott “containing charges of heresy and violating the usages of the diocese in the mode of conducting divine service.” The specific “heresies” which Father Prescott was reputed to have taught were: (1) that prayer might be addressed to the Virgin Mary, and (2) that auricular confession was both allowable and profitable. The ceremonial “aberrations” of which the priest was accused were: (1) the use of a surplice, and (2) the use of the psalter instead of the psalms in metre. After three trials these charges were declared to be “not sustained”, but the court decreed that, “inasmuch as the respondent had claimed the right to pronounce absolution to the penitent, he be suspended from the ministry until he furnish to the bishop a certificate renouncing that claim except in the office for the visitation of the sick or in cases of contagious diseases.” Father Prescott was technically banished from the Diocese of Massachusetts but the Bishop of Maryland (William Rollinson Whittingham) received him into his Diocese, officially releasing him from any obligation to obey the decision of the Massachusetts Court on the ground that “what a Bishop could do, a Bishop could undo.”

At the time his pastor was enduring Bishop Eastburn’s inquisition Charles Grafton entered the Harvard Law School where he remained for three years. During these years Grafton felt ever more strongly drawn to the Church and finally, “under Father Prescott’s influence, he offered himself as a candidate for holy orders to Bishop Whittingham. The Bishop was willing to receive Grafton and he took up residence as a theological student in the parish of Ascension Church, Westminster, Maryland, where Father Prescott was Rector. After due preparation he was ordained to the priesthood in 1858. In the course of the next seven years, during which Father Grafton engaged in parochial work, his thoughts began to turn to the revival of the Religious Life for men in the Anglican Communion, and the possibility of his own vocation to such a life. In order to determine more clearly the will of God for him he decided to go into retreat accompanied by Father Prescott.

The site selected for the retreat was Fire Island, Long Island, New York. The two retreatants hired an old shack on the southern coast of the island and sometime in the month of December, 1864, they embarked upon their unusual enterprise. The mornings were occupied in prayer and study. The two priests performed their own [2/3] housework, and cut up wood to provide warmth. Father Prescott performed the culinary duties. It will be recalled that while these two men peacefully pursued their spiritual exercises, the Country was engaged in a frightful civil war. But the war was to intrude itself even upon their isolated haven. One day a United States cutter anchored off shore and discharged a large number of marines and sailors who surrounded the house. The priests were suspected of being Confederate spies, and their possessions were thoroughly searched. Apparently the commanding officer was ultimately satisfied as to the loyalty of the two clergymen and they were molested no further. However, in spite of the fact that the United States Navy permitted the priests to remain on the island, the rigours of winter forced them to conclude the retreat and return to the mainland in time for Christmas.

What was accomplished on Fire Island? Here, for a brief space of time two Americans, two priests of the Episcopal Church, tried to live a form of the Religious Life and to ascertain the answers to profound questions stirring in their hearts. How we should appreciate having some sort of a record of the conversations which must have taken place at this time between Father Grafton and Father Prescott! It would seem obvious that they reached the conclusion that the two alone ought not to found an American monastic order at that time. Four earlier efforts had proved short-lived, and these priests doubtless felt that to secure a firm foundation they must seek help from abroad. Accordingly, in the spring of 1865, Father Grafton sailed for England. It was to be a matter of two or three years before he was joined there by Father Prescott.

II. THE SOCIETY BEGINS IN ENGLAND

SHORTLY after his arrival in England Father Grafton wrote to Father Prescott:

“By a series of wonderful providences, men are being drawn to a religious life, and are being drawn together. It is the most aweful and solemn of anything I ever knew, One feels every moment should be occupied in prayer, lest one may go wrong or thwart His Leadings or mar His Blessed work. The mercy of God has allowed me to know pf what has been done, and to see something of it, add, if I am not unworthy, of casting in my lot with it . . . If God will, very quietly indeed in the autumn, some persons will get together, and the work be begun. Some of England’s saintliest men will direct by their counsel the work, and some of them will be in it.”

[4] Among this saintly company, one to whom Father Grafton was drawn was Edward Bouverie Pusey. It was Pusey who led Grafton to Richard Meux Benson, Vicar of Cowley, a village two miles from Oxford. It has been recorded that on the memorable occasion of the first meeting between Father Benson and Father Grafton, the latter remarked, “I have come from America. Where is the man who longs to form a religious community in England. I want to find him.” To Richard Meux Benson who, like the ancient Hebrews, saw the finger of God in every event of life, this comment would undoubtedly have seemed nothing less than a divine communication. In view of his own thoughts and prayers and aspirations over the past years, these words from the lips of a foreign clergyman may have sounded like a clarion calling him to action.

One of the first concrete steps towards the formation of the Community took place in the summer of 1865 when Richard Meux Ben son, Charles Chapman Grafton, Alexander Penrose Forbes (later Bishop of Brechin), George S. Lane Fox, and the Rev. Reginald Tuke (curate of Saint Mary’s, Soho) met at Mr. Tuke’s rooms at St. Mary’s to discuss the formation of a religious order. It would seem that all eyes gravitated to the Vicar of Cowley as the logical leader. In July Father Benson wrote to Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford:

“I have been asked to head the movement and with a full conscious ness, all the while of my own incapacity for such a position, I can scarcely regard it otherwise than as a call from God, which I ought to accept. It does, indeed, seem to me as bringing with it an answer to the prayers of very many years which I had never contemplated.”

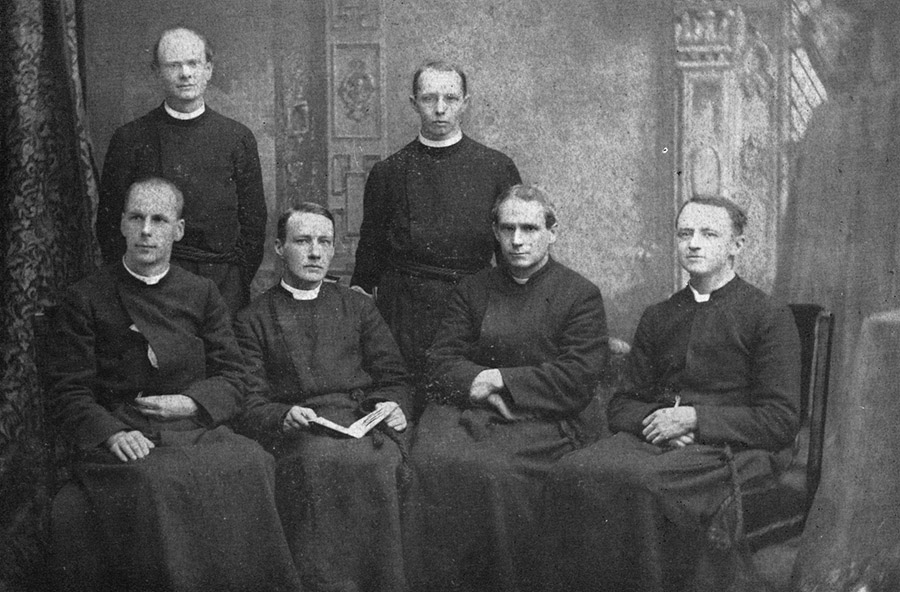

Towards the close of August, Father Grafton went to Cowley and took up residence with Father Benson in a small suburban brick house on the Iffley Road. Later in the year they were joined by Simeon Wilberforce O’Neill, a curate at Wantage. The three priests began in earnest to carry out, as a small Community, the principles of Holy Religion. Their intention was to create a Society consisting of both priests and laymen leading the mixed life of prayer, and active work in the world—particularly in conducting parochial missions and undertaking foreign missionary work. They assumed the title, “Mission Priests of Saint John the Evangelist.” They were sometimes known as “The Evangelist Fathers,” or “Johnians,” and, in the course of time received the label “Cowley Fathers,” because of their geographical location. Although certain features of modern religious orders of the Roman Catholic Church were imitated. Father [4/5] Benson wisely decided to return to the Benedictine custom of the corporate recitation of the Divine Office in chapel.

In a letter to Bishop Wilberforce Father Benson had explained:

“Our proposal was to live together for a twelvemonth, and at the end of that time to take vows for three years, renewable with the sanction of the Community, annually. At the end of a given period, say fifteen years, the vow might be made solemn.”

At the conclusion of a year’s trial period, Richard Meux Benson, Charles Chapman Grafton, and Simeon Wilberforce O’Neill gathered together on the Feast of Saint John the Evangelist, December 27th, 1866, and in each other’s presence took the following vow:

“In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. I . . . promise and vow to Almighty God, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, before the whole company of heaven, and before you, my Fathers, that I will live in celibacy, poverty, and obedience, as one of the Mission Priests of St. John the Evangelist unto my life’s end. So help me God.”

Thus the Society of Saint John the Evangelist formally came into existence.

From the very start, the Fathers seem to have entered upon a good deal of external work. Father Grafton preached, lectured, shepherded religious communities for women, counseled individuals, and conducted retreats and missions. In a letter to Father Prescott he wrote:

“I have no time to write sermons, and until I get back to Cowley very little for anything else.”

During the cholera epidemic which broke out in the summer of 1866, Father Grafton became a volunteer chaplain to a hospital in Shoreditch, and lodged with Pusey in East London. When Charles Fuge Lowder, the Vicar of Saint Peter’s, London Docks, became prostrated by the blow of having three of his assistants simultaneously secede to Rome in February of 1868, Father Grafton and Father O’Neill labored together for a time in his parish. One can not fail to admire this self-sacrificing, heroic work undertaken by Father Grafton but at the same time one wonders if this was really the best possible preparation for one desirous of developing the Religious Life in America. Father Benson and Father O’Neill, with their tremendous spiritual reserves, seem to have been little affected by external distractions, but few men have ever attained to their high level.

III. THE SOCIETY GAINS NEW MEMBERS

IT had, of course, always been Father Grafton’s desire to return to America to establish the Society there. Father Benson likewise hoped for the day when a branch of the Society should be planted on American soil. In October, 1868, in a letter addressed to his parishioners “of the New District of Cowley S. John on the opening of the Mission House in Marston Street,” Father Benson wrote:

“As the parishioners generally know, some of us are Americans, and it is hoped that they will some day return and organize in the western hemisphere a Mission Society like our own.”

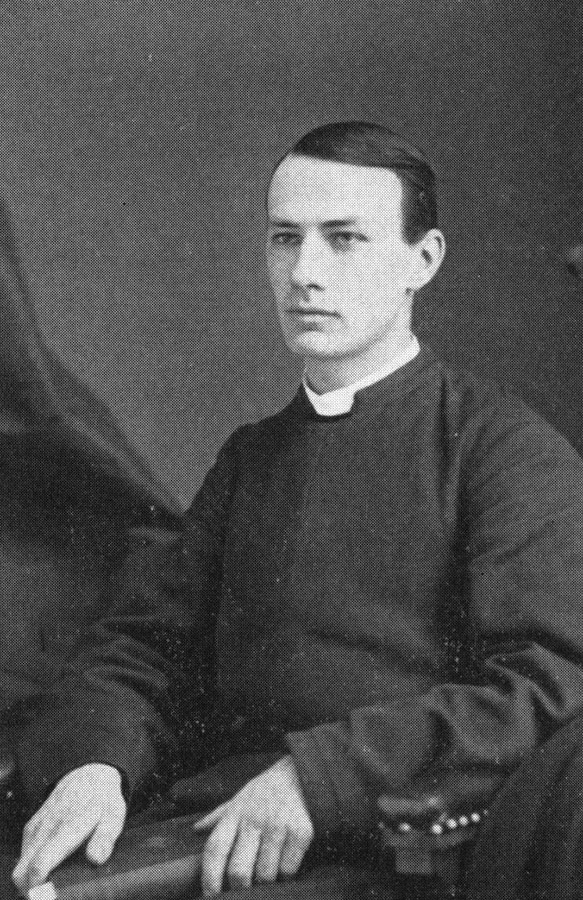

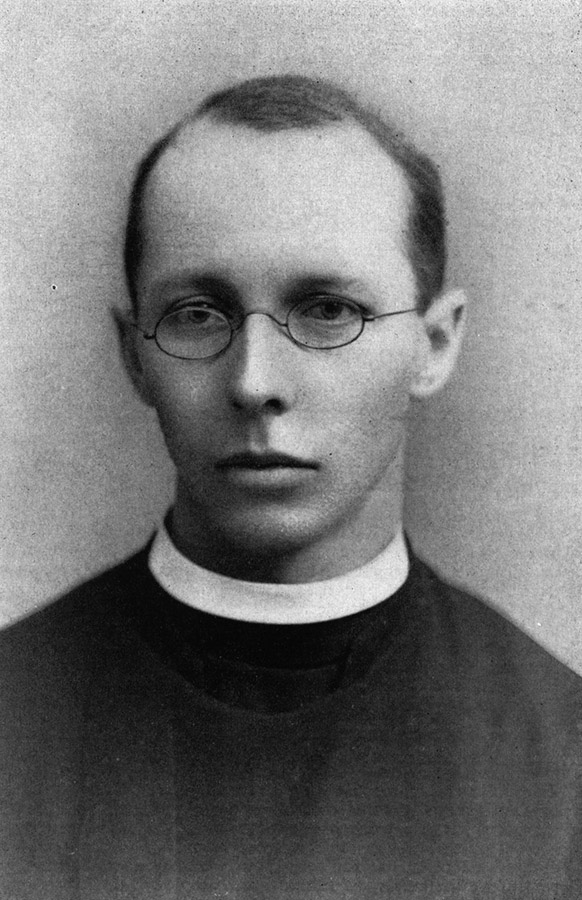

To forward this end, Father Grafton spent a portion of the years 1867 and 1868 in the United States endeavoring to enlist American recruits. In Baltimore he found no one interested in joining the Society. At the invitation of Charles B. Coffin, a student of the General Theological Seminary in New York, Father Grafton talked to some of the students there about the Religious Life. As a result, Charles Coffin, Freeborn Coggeshall, and Henry Martyn Torbert later sought admission into the Society. It may have been a fear of British domination which kept men from responding. This unreasonable attitude on the part of many Americans long served as a deterrent to American vocations in the Society of Saint John the Evangelist. Though the response to Father Grafton's plea in America was disappointingly small; a young Englishman was, at the same time, being drawn to Cowley, who in later years exerted a profound influence upon the Society in America, and upon the Episcopal Church. He was Arthur Crawshay Alliston Hall.

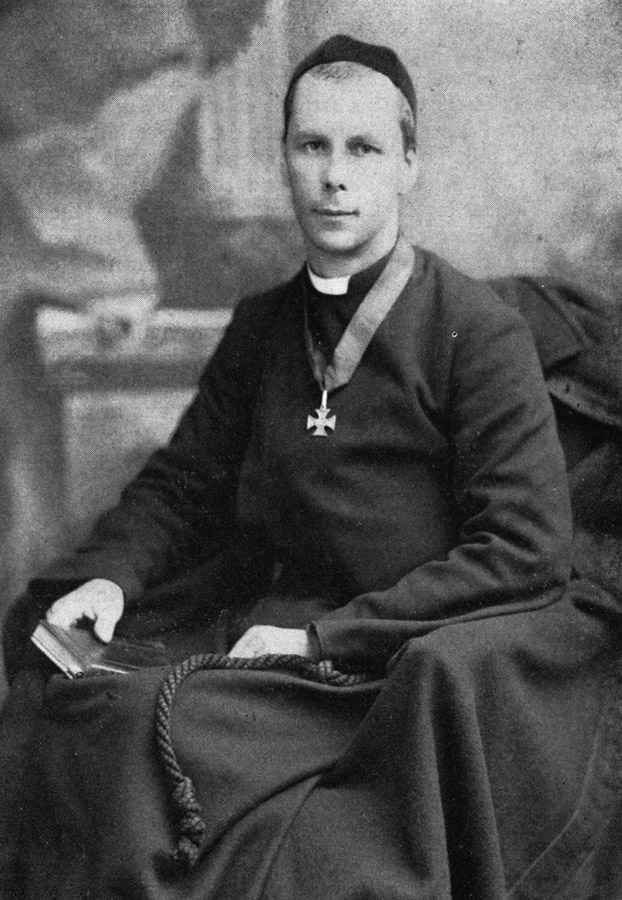

Born in Binfield, Berkshire in 1847, Arthur Hall went up to Oxford in 1865 and was enrolled at Christ Church. In November of 1867 he made his first retreat at Cowley, a retreat conducted by Father Benson, and at its close was received as an Associate of the Society. His university studies completed in 1869, Hall came to Cowley the following year to prepare for holy orders. On the Patronal Festival of the Society, the Feast of Saint John before the Latin Gate, May 6th, 1870, he, along with Robert Lay Page (his future Superior at the time of the Brooks controversy) received the habit of the Society. In December he was ordered deacon in Christ Church Cathedral by Bishop John Fieider Mackamess who had become the Oxford Diocesan the previous January, following the translation of Bishop Wilberforce to Winchester in November of 1869. In his biography of Arthur C. A. Hall, George Lynde Richardson writes, concerning the new deacon:

[7] “New in the ministry as he was, he had already made a deep impression upon his associates by his strength of purpose and his capacity for getting things done, and the youthful deacon (he was only twenty-three) was made Master of the lay brothers, and was set to work visiting, preaching, teaching Confirmation classes, catechizing children.”

On the Feast of Saint Thomas, December the 21st, 1871, Bishop Mackarness ordained the young deacon to the priesthood, and licensed him as a mission priest in the Diocese of Oxford. It was not long before Father Hall’s reputation as a preacher became widespread. Two years later he was assigned to conduct his first parochial missions—the first at Kempston during Lent, the second at Eastbourne in June when he was accompanied by Oliver Sherman Prescott.

Father Prescott, who became Rector of Christ Church, West Haven, Connecticut, in 1865, the year Father Grafton went to England, had remained in constant communication with his close friend. Father Grafton’s letters to Father Prescott contain repeated appeals that the latter come to Oxford. It would seem that Father Prescott entertained fears that should he go to England he might never be sent back to his native land. In a letter written from New York on October 1st, 1867, Father Grafton explained:

“As to your returning; I feel that it will be absolutely useless for me to attempt anything in this Country without four persons to begin with . . . I really think it would be better for you to go out to England, and to leave the question as to your return to be settled out there.”

Father Prescott finally made his decision, went to Cowley, and was clothed as a novice in the Society in 1868 in the oratory of the old house on the Iffley Road, where the first three professions had been made. He took his life vows two years later, on the same day that A. C. A. Hall, R. L. Page, J. Greatheed, and Henry Darby received the habit. Father Prescott’s profession brought to four the total number of Professed Fathers, and for the next two years the Society remained half English and half American. Perhaps it was at this time that Dr. Liddon laughingly suggested to Father Benson that he put the American eagle over his door since he had such a proportion from the United States!

IV. THE FATHERS ARRIVE IN AMERICA

Not only were Englishmen beginning to be aware of America’s role in the newly-founded Order, but Americans were recognizing the existence of the new Society in England. St. Clement’s Church, Philadelphia was the first parish in America to [7/8] receive the ministrations of a Professed Cowley Father. Despite his earlier anxieties about returning to America, Father Prescott was sent to St. Clement’s just a few months following his profession, to assist the Reverend Herman Griswold Batterson who had become rector in 1869.

At this same time the Parish of the Advent, Boston, now worshipping in the church on Bowdoin Street, once more found itself without a rector. Following the death of William Croswell, in 1851, Horatio Southgate, formerly Bishop of Constantinople, assumed the rectorship. He was followed by James A. Bolles who resigned the parish in 1870. At a meeting of the committee appointed to consider the vacancy in the rectorship, held October the 7th, 1870, Mr. Richard Dana explained the work of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist and recommended the passage of the following vote:

“That the committee to nominate a rector be authorized to make temporary arrangements with the Rev. Mr. Benson, of Oxford, to assist the rector ad interim in carrying on the work of the parish.”

This recommendation was adopted and arrangements satisfactory to Father Benson were ultimately made. Father Benson himself came, accompanied by Father O’Neill and the Reverend Frederick William Puller, who was, at that time, assistant priest at St. Paul’s, Lorrimore Square, London, and who was to enter the Society of Saint John the Evangelist in 1880. Father Grafton remained at Cowley to be in charge of the Community. Father Page, though still a novice, had the charge of the Cowley parish of which Father Benson still remained vicar.

The three English priests reached Boston on Saturday, November the 12th, 1870. “Father Benson has arrived with 40 monks to convert the heathen!” Thus announced the headlines of some news papers. Misunderstanding and suspicion doubtlessly colored the minds of some Americans but many extended a most cordial welcome to the priests. The most vigorous opposition emanated from the very area in which the Fathers had been invited to work—the Diocese of Massachusetts. “Iciness” would be a mild noun to use in describing the manner in which Manton Eastburn, still the Diocesan, greeted the arrival of the Fathers. He even went so far as to refuse to see them in spite of the fact that Father Benson brought letters from the Bishop of Oxford (Mackarness), the Bishop of Winchester (Wilberforce), and the Bishop of London (John Jackson). In the book, A Sketch of the History of the Parish of the Advent in the City of Boston, 1844-1894, we read, concerning the Bishop’s attitude:—

[10] “The result was a correspondence which extended through the fall and winter of 1870-71, in which, while the parish was not technically involved, its committee was put to much embarrassment. These clergymen had been invited by the parish, and the parish felt in a measure responsible for the manner in which they were received by the ecclesiastical authority of the diocese . . . it was finally arranged, however, that the Rev. Charles C. Grafton and the Rev. Oliver S. Prescott, members of the society, who, as priests of the American Church, were canonically eligible, should take active charge of the services of the parish, while the English members should hold such meetings in the Sunday-school-room and elsewhere as might be held by any laymen, performing no priestly acts in this diocese so long as the bishop objected.”

Father Benson was a man with tremendous respect for authority and he felt bishops should be obeyed. Therefore he obeyed!

Sometime between the promulgation of Eastburn’s ban on the Englishmen and the following March, Father Prescott removed from St. Clement’s and came to the Advent to work with, the Reverend Moses B. Stickney who was serving as rector ad interim. After Stickney resigned his connection with the Parish on April 10th, 1871, Father Prescott was in charge of the Church. Apparently dis abilities imposed upon Father Prescott by the Diocese of Massachusetts twenty years previously had been removed.

V. A MISSIONARY TOUR IN THE NEW WORLD

WHAT the Diocese of Massachusetts lost through Bishop Eastburn’s practical ostracism of the English Fathers was gained by Churchmen elsewhere in the United States and by Anglicans in the Bahamas and Eastern Canada, for the Fathers travelled widely, preaching, counseling, and conducting missions and retreats. The schedule which the three English priests pursued in the course of the first nine months of 1871 was truly exhausting.

In February Father Benson and Father O’Neill sailed from New York for the Diocese of Nassau, then headed by Bishop Addington Robert Peel Venables. Following a brief retreat for the clergy, Father Benson returned to New York and, among other, activities, addressed the students at the General Theological Seminary. Father O’Neill stayed on in Nassau holding services and engaging in an extensive missionary tour of the Bahamas.

During Lent Father Benson and Father Puller were in the western part of America. Carrying a heavy Lenten schedule. Father Benson was at the Chicago Cathedral each week from Friday to Monday, at Racine College on Tuesdays, and at two churches in Milwaukee on Thursdays. Father Puller spent the first half of Lent with the [10/11] Reverend James DeKoven at Racine, Wisconsin, and the second half with Canon Durling at Janesville, Wisconsin. Both men visited Nashotah House, and after Easter they spent a few days with the Bishop of Minnesota, Henry Benjamin Whipple, in Faribault.

From the West the two Englishmen now travelled eastward to Baltimore where they conducted series of missions and Father Benson gave a clergy retreat. A visit to the Nation’s Capital was squeezed in before their departure for New York. Father Puller, reminiscing about this period, writes,

“While at New York we visited Bishop Horatio Potter, and we also went up the Hudson River and spent a night in a hotel on the top of the Catskills.”

Later they passed another month in Boston and then moved north ward to Toronto and Montreal. Father O’Neill, who was back from the Bahamas by June, visited West Point on July 9th and moved on into the western part of New York State. Later in the month he conducted a mission at Campobello, New Brunswick, and joined Father Benson in the early part of August for another mission in Saint Peter’s Church (now Saint Peter’s Cathedral) in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. While Father O’Neill was holding his mission in Campobello, Father Puller was conducting one in Saint Stephen, New Brunswick. After preaching in four little churches in the country district around Fredericton, New Brunswick, Father Benson moved on into Nova Scotia for a clergy retreat and for missions in Windsor and Halifax.

But the labors on this side of the Atlantic were terminating for the year 1871. The three Englishmen—Father Benson, Father O’Neill, and Father Puller—assembled at Halifax in September preparatory to their departure from the new world. Surely the frustration of their desires to minister in the Church of the Advent, Boston, had proved a source of keen disappointment, but the Fathers had turned their adversity into a great opportunity to minister to the souls of many in an ever-widening circle. They had sown good seed, and now returned to Cowley to commit the Boston work into the hands of another—Charles C. Grafton.

VI. FATHER GRAFTON AT THE HELM IN AMERICA

FATHER GRAFTON, accompanied by the Reverend Henry Darby, a novice, left Cowley on the 20th of November, 1871. Appreciation was expressed for the Father’s work in England, and prayers were requested for God’s blessing upon the Society’s work which the Father was to forward in America. We read in the Cowley Saint ]ohn Parish Magazine for December, 1871:—

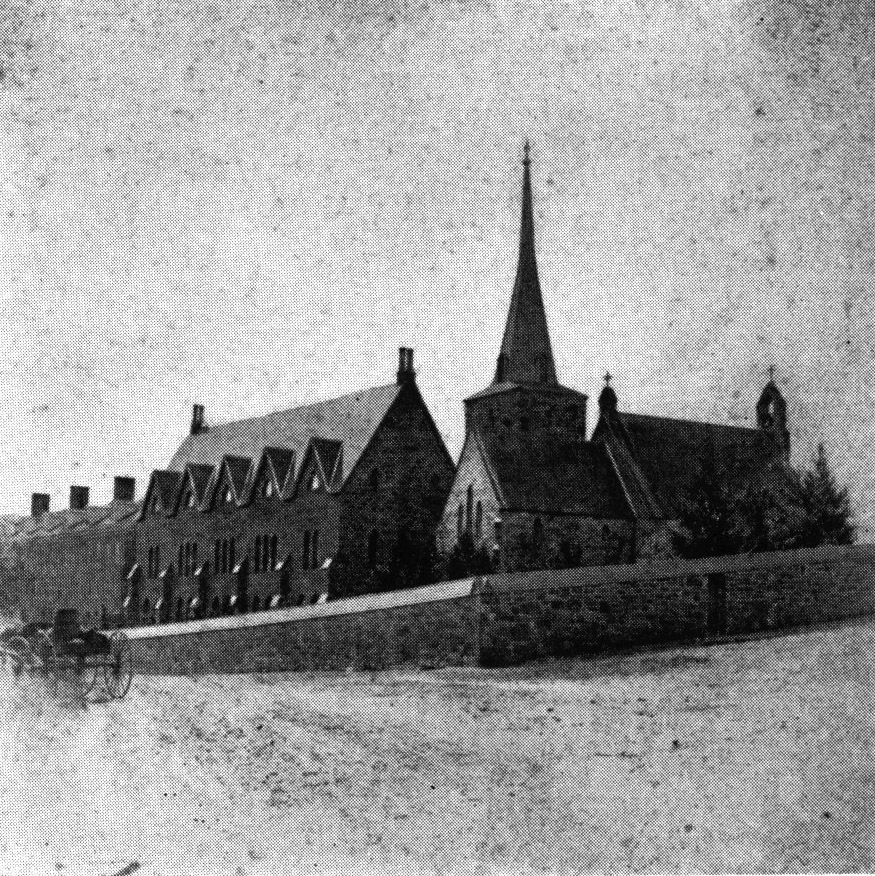

“It is now six years since he (i.e. Father Grafton) first came amongst us, and during that time his ministrations have been greatly valued and blessed to very many not only of our own parish but throughout the country. It is not needful here to enlarge upon the affection and esteem he has won amongst us. The prayers of all are asked that their ship may have a prosperous voyage and the work in America, of which Fr. Grafton will be the head, may be abundantly blessed. He will immediately take charge of the Church and College belonging to the Society of the Evangelist Fathers, at Bridgeport, Conn, and will superintend all the mission work which they may be called upon to carry on in the different parts of the western continent. Fr. Prescott continues still actively engaged at the Church of the Advent, at Boston. The Church work in that city is by God’s mercy rapidly developing under his care. Many persons outside the Church are coming to inquire with interest into her doctrine and practice.”

This excerpt clarifies the fact that the American work of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist now radiated from two focal points—Boston and Bridgeport. In Boston the brethren resided in a house located at #22 Staniford Street, a building which has since been razed.

The Bridgeport property, consisting of the Church of the Nativity and the house and grounds adjoining it, seems to have been built and owned by the Reverend E. Ferris Bishop who apparently donated the property to the Society. Doubtlessly there was a considerable exchange of personnel between the Bridgeport and Boston Houses. For a time in 1872 the Reverend Edward Benedict, a postulant, was in charge of the Bridgeport House, and the Reverend Henry Darby, the English novice, was with him. Numbers began to grow as Ameri cans and Englishmen alike joined hands to promote a common cause in the United States. Freeborn Coggeshall was admitted as a postulant into the Society on December 29th, 1871. In July of the following year three men were sent out from Cowley—Father John Greatheed, Brother Charles Edwyn Gardner, and Brother Charles (Wilson).

In the summer of 1873 Father Grafton returned to Cowley for the annual retreat, a custom frequently repeated in the early days by the Fathers working in America. The summer retreat was of a month’s duration until the Chapter of 1884 when it was decided unanimously to shorten it henceforth to two weeks. On his return to Boston in September, Father Grafton was accompanied by Father Hall, Brother William, and three of the Sisters of Saint Margaret—Mother Louisa Mary, Sister Theresa, and Sister Jessie. On September 14th, just prior to their departure from East Grinstead, Sister [13/15] Louisa Mary had been appointed Mother Superior of the house to be newly established in America and Father Grafton was instituted as their Chaplain. Two years earlier Sister Theresa had been sent to Boston to take charge of the Children’s Hospital and she was now returning to continue her good labors there while the other two Sisters worked in the Parish of the Advent. Thus began a close relationship between the members of what were to become the American Congregations of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist and the Society of Saint Margaret—a contact which happily continues to the present day.

At All Saints, 1873, the Society of Saint John the Evangelist took formal possession of the House of our Saviour and the Church of the Nativity, Bridgeport. Although still a novice himself. Father Hall was placed in charge of the House and appointed Novice Master. The Reverend Edward Benedict, the Reverend John Robert son, Brother Gardner, and Brother Charles were there with Father Hall most of the time. Father Freeborn Coggeshall, Father Darby, Father Henry Martyn Torbert, and George Johnson were with him for part of the time. Father Greatheed and Brother William, stationed at the Boston House, journeyed to the House of our Saviour from time to time for retreat. In a letter to Father Convers written in 1920, Bishop Hall comments,

“We had a happy time in Bridgeport for a year, with study and spiritual instructions in the House, and services, with the pastoral cate of the people around in North Bridgeport.”

Ecclesiastical difficulties, however, still existed. Bishop Eastburn of Massachusetts had died in 1872. His successor, Benjamin Henry Paddock, was consecrated on September 17th, 1873, while Father Grafton, Father Hall, and Brother William were on the ocean. Bishop Paddock was apparently willing to license Father Hall, though an Englishman, as a visitor in the Diocese of Massachusetts, but the Bishop of Connecticut (John Williams) proved obdurate, refusing to recognize Father Hall. Confirmation candidates from the Church of the Nativity had to be presented in Trinity Church, Bridgeport, and the Bishop stipulated that Father Hall was neither to present the Confirmation Classes, nor even to be present in the chancel of the church during the Confirmation Service.

Despite this irregularity in his ecclesiastical status, we may have no doubt that Father Hall was able, on the basis of his own training at Cowley, to impart to the novices entrusted to his care much concerning the basic principles and practices of the religious life. Father Benson seems, to have considered the House of our Saviour [15/16] an excellent place for the novitiate for he wrote from Cowley to Brother Gardner,

“I think, if I had my own way, I should come with all the novices.”

Since that was not possible it was considered wise to send American novices to Cowley for a portion of their training in order for them to learn at first hand the spirit of the Society and its consecrated Founder. Accordingly, in the summer of 1874, three priest postulants—Freeborn Coggeshall, Henry Martyn Torbert, and Edward Benedict journeyed to England for their pre-clothing retreat and to receive the habit of the Society. Father Coggeshall, writing aboard “The Batavia” on June 29th, 1874, says,

“A very good passage, so far. Have not been sick but have steered close to it . . . Fathers Benedict and Torbert were both sick. We had daily Celebrations in our stateroom, save on two days.”

It was well that these postulants had gone to England, for the Bridgeport undertaking had to be abandoned five months after their departure. The donor of the property, the Reverend E. Ferris Bishop, seems to have been an extravagant ritualist to say the least. The deed for the property had never been registered and the donor now insisted upon inserting in the deed of gift conditions which Father Grafton deemed inconsistent with conformity to the Book of Common Prayer. In his letter of March 12th, 1920, to Father Convers; to which we have already referred. Bishop Hall wrote, concerning the action of the Reverend E. Ferris Bishop,

“His special grievance was that we would not say the Commandments sotto voce while his son Sidney played a nine-fold Kyrie . . . They wanted the organ going all through the prayer of Consecration, and if I remember rightly, perhaps singing that on a tone. I think there were other things, but I don’t remember what they were.”

The upshot of the whole matter was that the Society withdrew on Thanksgiving Day, 1874, Father Hall and Brother Gardner returning to Boston. The American Literary Churchman of November 1st, 1882, concludes,

“Without hesitation the Fathers sacrificed to the rubrics a property worth $60,000.”

VII. THE CALL TO SAINT CLEMENT’S

Difficulties, far weightier than the loss of a valuable piece of property now lay ahead. In Lent of 1874 Father Grafton and Father Luke Rivington, one of the English Fathers (professed in July of that year), conducted a memorable mission in Saint Clement’s Church, Philadelphia. This led ultimately to a [16/18] request that the Society of Saint John the Evangelist assume charge of the parish under the direction of Father Prescott. In the minutes of the vestry meeting convened on October 5th, 1875, the following resolution appears;

“Resolved, that a Committee of three be appointed to wait upon the Rev. Fr. Oliver Prescott, S.S.J.E., and ascertain his views respecting the taking charge of St. Clement’s Church and Parish by the Evangelist Fathers.”

The Father Superior in England (Father Benson) assented to this proposal and on Septuagesima Sunday, February 12th, 1876 Father Prescott assumed the rectorship of St. Clement’s. Associated with him at the start were three priest novices from England—Basil William Maturin, George Edmund Sheppard, and Charles Neale Field. These are great names, and to the list must be added the names of Father Benson, Father Convers, Father Longridge, and others who participated in the life of the parish during the fifteen years that the Society administered St. Clement’s. Father Franklin Joiner, for many years rector of St. Clement’s, writes,

“This period has usually been looked upon as the ‘golden age’ of the Parish, and many people still date events from the ‘days of the Fathers.’”

But before the year 1876 was out, the trouble to which we referred broke out. Like Manton Eastburn and John Williams, William Bacon Stevens, the Bishop of Pennsylvania, proved to be very much opposed to the Society of Saint John the Evangelist. A letter from the Bishop to Father Maturin, dated October 18th, 1876, reads:—

“After long and prayerful consideration of the subject, I deem it a duty, which I owe to myself and to my Diocese, to revoke the verbal and temporary permission to officiate in this Diocese, which I gave you through the Rev. Mr. Prescott a few months ago, and to request you to discontinue all clerical ministrations within the Diocese of Pennsylvania, as I do not consent to your officiating in this ecclesiastical jurisdiction.”

Some older members of St. Clement’s believe that this sudden inhibition resulted from the newspaper reports of a sermon Father Maturin preached on the Real Presence. In a further letter, dated October 19th, 1876, Bishop Stevens returned Father Maturin’s certificate from the Bishop of Oxford (Mackarness). Fortunately the Society’s good friend Horatio Potter,, the Bishop of New York, was willing to receive Father Maturin’s credentials and he thereby became canonically connected with the Diocese of New York.

On the same day that Bishop Stevens inhibited Father Maturin he felt it his duty to censure Father Prescott. His complaint was [18/19] that he had learned that in “daily celebrations of the Lord’s Supper” Father Prescott did not use in its entirety the form prescribed by the Book of Common Prayer but omitted certain elements and added others. Father Prescott turned this communication over to the members of the vestry of St. Clement’s, who wrote a letter of protest to the Bishop on November 7th in which they concluded:—

“It will be our duty, as it will be our endeavor, under all circum stances, to maintain the ecclesiastical and legal rights of this Parish.”

This tiff about ceremonial marked the beginning of what was to develop into a serious controversy during the Diocesan Convention of 1879.

VIII. A VISITATION FROM FATHER BENSON

Five days after the vestry’s reply to Bishop Stevens, Father Benson arrived at St. Clement’s. It must have pained him much to learn of these unpleasant developments. More than this he now faced the sad task of seeing a beloved novice laid to rest. The Society of Saint John the Evangelist, almost ten years after its inception, had experienced its first loss through death. Freeborn Coggeshall, the American priest postulant who had voyaged to England in 1874 was even then suffering from asthma. Other illnesses afflicted him in England, and he passed away on October the 6th, 1876, at Cowley. It was hoped to place his earthly remains in the parish cemetery there, but friends in Rhode Island asked that the body be returned to America. This request was granted, and the remains were shipped aboard the “Egypt” which reached New York just ahead of Father Benson’s ship. On Wednesday, November 15th, Father Benson, with five other members of the Society, attended Father Coggeshall’s funeral in Providence. Father Benson wrote, after the funeral:—

“Much as one regretted not having him laid, as once was hoped, in the new burial ground at Cowley, yet after one saw the interest which his return awakened at Providence, one could not regret the voyage. His life was a short one, but his work will live for ever.”

Father Benson, in addition to viewing the newly-undertaken work of the Society in Philadelphia, doubtless spent some time with his spiritual sons in Boston. In December of 1876 he made a proposition to the Corporation of the Parish of the Advent, Boston, regarding the purchase of the church building on Bowdoin Street. This offer was probably made because of the fact that the year previously the Parish had purchased a new building site on Brimmer Street. After some deliberation Father Benson’s proposal was accepted in March, 1877, on condition, however, that,

[20] “as long as the parish may have for its rector a member of the Society of St. John the Evangelist, the church on Brimmer Street shall be made the headquarters of the work of the Society in Boston, and the church on Bowdoin Street shall be carried on as a mission chapel, subject to the control of the said rector, but independent of said parish.”

In the book, A Sketch of the History of the Parish of the Advent, we read,

“The price fixed for the property on Bowdoin Street was about $27,000, which was raised by a contribution of £2,000 sent by Father Benson from England, and the remainder by Father Grafton and several members of the parish.”

In addition to their parochial duties at the Church of the Advent and St. Clement’s, the Fathers continued to carry on the work of conducting missions and retreats. Father Hall and Father Maturin preached a mission in the House of Prayer, Newark in May of 1877, and in the Church of the Ascension, Chicago, the following month.

In July, Father Hall and Father Maturin returned to Cowley for the annual summer retreat and to take their life vows, along with Father Edward Benedict, who had gone to England with Father Coggeshall and Father Torbert. Father Torbert had left the novitiate before the time for his profession, feeling that he could not take vows from which the American Church provided no dispensation. On his return to the States he ministered for seven years to the Sisters of Saint Mary at Peekskill, and then assisted the Fathers in Boston. Father Benedict was unable to persevere in his vocation. Broken in health, he withdrew after his profession, and was ultimately released from the Society.

A month after his profession at Cowley, Father Hall returned to the Church of the Advent, Boston. Since the end of 1875, when Father Grafton went abroad for a prolonged stay. Father Hall had been in charge of the parish, and had also ministered to the spiritual needs of the Sisters of Saint Margaret. Father Grafton finally re turned to Boston in November of 1877.

In January, 1878, a new face appeared in the sanctuary of the Advent—the face of one who is still affectionately remembered by some—that of Edward William Osborne. Father Osborne was born in Calcutta on January 5th, 1845, the son of a Church Missionary Society missionary in India. He had been ordered a deacon in 1869 and advanced to the priesthood the following year. After serving two curacies in country places in England he entered the Society, becoming a postulant on January 25th, 1876, and a novice the following August. As Freeborn Coggeshall lay dying at Cowley, Father [20/21] Osborne stood at his bedside and recited the commendatory prayer for his soul. The work which Father Coggeshall might have under taken fell to Father Osborne and he was soon sent to America to begin a remarkable ministry, one which was ta lead at length to his consecration as Bishop of Springfield, Illinois.

IX. TRIBULATION IN PHILADELPHIA

MEANWHILE, Bishop Stevens and Father Prescott continued to differ in Philadelphia. On January 27th, 1877 the Bishop wrote to the rector requesting the abandonment of certain customs at St. Clement’s, including the omission of the “Longer Exhortation” and the use of acolytes. Father Prescott requested that the Bishop make an official canonical visitation of St. Clement’s, feeling that when the Bishop observed the great work the Fathers were performing his attitude might change. The Bishop visited the parish on February 17th, but he remained adamant, still insisting that the practices he had condemned in his earlier letter be discontinued. Now the vestry entered the dispute announcing,

“We declare and announce as our solemn conviction that the rector should not accede to the demand made upon him in such letters.”

Father Prescott expressed his willingness to make some compromises, but the Bishop insisted upon having all his requests carried out, and declared that further correspondence was unnecessary.

Beside Bishop Stevens, the Society found a further clerical opponent in the Dean of the Philadelphia Divinity School, the Reverend Dr. Daniel R. Goodwin, who proved tireless in his efforts to heap ignominy upon St. Clement’s and its rector. At the Diocesan Convention which convened on May 9th, 1878, Dr. Goodwin opened a discussion on the subject of St. Clement’s Church. After much talk, a resolution was passed providing for the appointment of an investigating committee which should “ascertain the facts” about the usages and modes of worship at St. Clement’s, and recommend some action to the next Convention.

The committee of investigation reported to the Diocesan Convention, meeting in the Church of the Epiphany, Philadelphia, from May 6th to May 9th, 1879, the “abominations” being perpetrated at St. Clement’s. The committee then recommended:

(1) That the Convention condemn the “practices and usages . . . ascertained to be followed in St. Clement’s Church”;

(2) That a diocesan canon be written by which a parish maintaining or permitting “usages or practices not in conformity [21/22] with the doctrines, discipline, and worship of the Protestant Episcopal Church” might be deprived of its representation in the Convention”; and

(3) That the report “be referred to the Bishop and the Standing Committee to take such action thereon, under existing legislation, as they think requisite and proper.”

These recommendations provoked a torrent of acrimonious debate. Many delegates who had no sympathy with St. Clement’s felt that the question under discussion involved an important point of constitutional rights, and that the proposed canon was fraught with danger. There were occasional outbursts of laughter and applause from the church galleries so disturbing to the delegates that the Bishop threatened to clear out the spectators. At one point in the discussion. Father Prescott arose to assert that when the Convention got through it would leave him and the services at St. Clement’s just where it found them; that those services would not be changed except by and under and in accordance with the laws and constitution of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. Later, in desperation. Father Prescott again took the floor to announce,

“My word has been so often flung back in my teeth that my voice will no longer be heard in the convention.”

All of the recommendations of the committee were finally adopted. The new diocesan canon forbade any “ritual” not sanctioned by the Bishop, and also the use of the Sacrament of Penance, unless the practice could be proved to have been the usage of the parish for the preceding twenty years. Father Joiner in his articles on St. Clement’s explains,

“This canon apparently was never enforced and was removed some years later by an overwhelmingly large vote of the Convention.”

The month following the famous Convention of 1879, Bishop Stevens requested that proceedings be inaugurated against the Rector of St. Clement’s under Title I, Canon 22, “Of the Use of the Book of Common Prayer” of the Canons of the Episcopal Church. This was the notorious “Ritual Canon” passed by the General Convention of 1874, and which no longer appears among the Canons of the Church, having later been repealed. Hearings by the Bishop and Standing Committee began on January 20th, 1880. In February, Father Benson made a hurried trip to Philadelphia from England, apparently to appraise the situation at first hand. As a result of the hearings, Father Prescott was found guilty of bowing to the altar, the use of candles, the wearing of vestments, the elevation of the [22/23] Blessed Sacrament, celebrating without communicating the congregation, and the omission of the “Longer Exhortation.” According to the stipulation of the Canon, Father Prescott was admonished by the Bishop to discontinue such practices. Father Prescott’s protest against the decision resulted in the threat of a trial for deposition, so that on May 5th, Father Prescott, Father Maturin, and the Reverend Duncan Convers, who was now on the staff of St. Clement’s, resigned.

The vestry requested that the Fathers withdraw their resignations and put the questioned ceremonial in abeyance. This was done, and beginning with the Sunday in the Octave of the Ascension, May 9th, 1880, bowing, genuflections, and the use of altar lights were omitted, the “Longer Exhortation” was invariably used, and Mass vestments were replaced by a surplice and black stole. These ceremonial arrangements continued in effect for a full year and a half.

Surely these controversies, widely publicized in the secular and religious press in America, must have caused grave concern to the Father Superior at Cowley. Twice in 1880 Father Benson made the long journey to the United States, both at the beginning and the end of the year, to endeavor to iron out the difficulties. He attempted loyally to support his spiritual son, Oliver Prescott, and yet we know he did not always agree with him and his policies. He wrote, concerning the situation at St. Clement’s,

“Some things . . . would have been different if I had had control of the parochial management. I certainly should have urged more hearty acceptance of episcopal authority.”

When the situation had become well nigh intolerable. Father Benson made it clear that either Father Prescott would have to resign as Rector of St. Clement’s, or the Society of St. John the Evangelist would withdraw from the parish. Father Prescott felt so strongly that it was his duty to remain as Rector of St. Clement’s that he went so far as to request his arch-enemy. Bishop Stevens, to intervene on his behalf. The people of the parish were highly incensed over this appeal to the Diocesan, having no desire whatsoever to terminate their relationship with the Society. Accordingly, the wardens and vestrymen of St. Clement’s requested that Father Prescott tender his resignation as Rector, which he reluctantly did in November of 1881.

Basil William Maturin, S.S.J.E., now became the Rector of St. Clement’s Church. Bishop Stevens, it will be recalled, had inhibited Father Maturin in October of 1876, but the inhibition was withdrawn six months later, perhaps in consequence of vigorous protests which the Diocesan received from Bishops of the Church of England, [23/25] including, some assert, the Archbishop of Canterbury (Archibald Campbell Tait). Father Maturin restored the old, accustomed ceremonial, and introduced the use of incense. Of this new period at the Church, Father Joiner writes,

“It was during Father Maturin’s rectorship that St. Clement’s achieved its greatest glory and reputation. Father Maturin was one of the mighty preachers of the Church. Crowds came to hear him and it is said that police were required every Sunday to handle the crowds and keep them in order. What the newspapers of the day called ‘a mass of seething humanity’ crowded the corridors and aisles of the church. People tell how week after week they have seen the window sills, the choir, and the pulpit steps jammed with the overflowing congregations.”

Such a description suggests that charity, rather than uncharitableness, once more permeated the City of Brotherly Love.

X. A DUSTSTORM STRIKES BOSTON

PEACE had come to St. Clement’s, Philadelphia, but strife now broke out at the Church of the Advent, Boston. A like question arose in both places. When a religious becomes the rector of a parish how much freedom of action may he exercise? No matter what his assigned work a priest who is a regular is never dispensed from obedience to his superior. A wise superior, having assigned a member of his order to supervise a parish will, of course, leave the practical management of parochial affairs to the wisdom and discretion of the priest.

It is important that this basic fact be thoroughly understood because it was involved in the controversies which raged around Father Prescott, Father Grafton, and Father Hall. Reading those seemingly endless articles in the secular and religious press in 1882 one is driven to the conclusion that most contributors, writing in heat, merely betrayed marked ignorance of the organization and obligations of a religious community. Father Benson, ever acting in good faith, simply carried out his duties as the Superior of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist; but his American opponents continued to brand him as a meddling Britisher who had entirely overstepped the bounds of his authority.

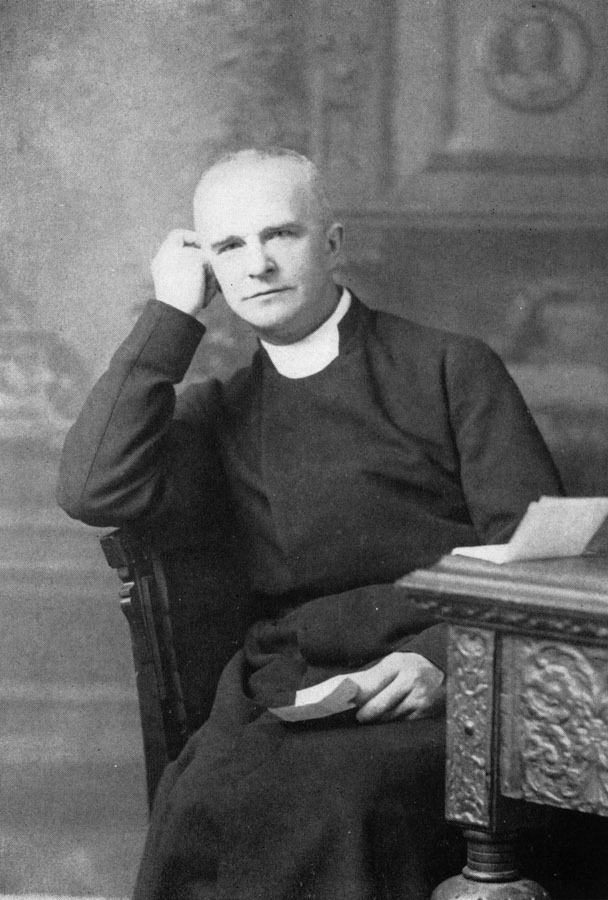

Charles Chapman Grafton felt he was called to be in America a superior whose position was the equivalent of that of Richard Meux Benson in England; but despite great natural gifts and spiritual powers some of the Fathers, including’ the Founder, felt that Father Grafton lacked certain necessary qualities essential to the leadership of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist in [25/26] America. For two full years (1875-1877), due to illness, he was obliged to absent himself from the Church of the Advent, of which he was the Rector. The state of his health, added to other matters, seemed to make it clear that Father Grafton could not head an American branch of the Society. However, when Father Benson expressed this as his own earnest opinion. Father Grafton felt that he must force a separation from the Society.

For some time Father Grafton had been agitating for the writing of a Constitution for the Society of Saint John the Evangelist. There was an understandable reluctance on the part of the Founder to effect this during the formative years of the Society’s life. In October of 1881 Father Grafton wrote an open letter to Frederic Dan Huntington, the Bishop of Central New York, in which He stated,

“We have as yet no constitution, only a spiritual rule of life. In the formation of the former we desire the advice and assistance of those set over us in the Lord. We are under no obligations to any Superior which do not leave entirely undisturbed the obligations we owe as clergy to our Bishops . . . Such a Society must, in order to have the moral support of the Bishops . . . submit its constitution and rule of life to their approval.”

By writing this letter Father Grafton presented the issue between him and his Superior as essentially a contest between the rights of the Episcopal Church and her Bishops as against those of foreign ecclesiastics. The matter thus presented led to considerable contro versy. The newspapers eagerly took up the question and people began to ally themselves with one side or the other.

The duststorm assumed such proportions that four members of the Society (Fathers Grafton, Hall, Maturin, and Osborne) conferred at the Mission House in Staniford Street, Boston, in the early part of June, 1882. They considered three possible courses of action:

(1) That Father Grafton and those who felt as he did, submit and wait until their grievances could be righted.

(2) That Father Grafton withdraw from the Society and resign his rectorship.

(3) That Father Grafton be released from the Society, retain his rectorship, and that Fathers Hall and Osborne leave the Church of the Advent.

These suggestions were thoroughly discussed as to their effect upon the Society, the parish, and the individuals involved. It was recommended that Father Grafton cease writing to the newspapers [26/27] and accept Father Benson’s decision, but at the close of the conference Father Grafton could only conclude,

“I see more and more that I have no place in the Society any longer.”

A few days after this conference Father Hall received directions from Father Benson to leave for British Columbia where, with Father George Edmund Sheppard, he was to labor so heroically among the men constructing the Canadian Pacific Railway. Father Hall’s departure proved a two-fold blessing. He and Father Sheppard were able to come to the aid of the Bishop of New Westminster (A. W. Sillitoe) in a great emergency, and they were both removed from all the trouble brewing in Boston.

On the 16th of June Father Grafton wrote to the Superior suggesting the terms of his separation from the Society, namely that he and the Americans who might so elect be released, and that property matters be settled between the Society and those with drawing. In his reply of July 4th Father Benson wrote magnanimously,

“God forbid that I should hold you down under obligations of past vows of obedience if they have become a burden to conscience.”

After reading the Superior’s communication to Father Osborne, Father Grafton concluded,

“You will understand therefore Father Osborne, that I am no longer a member of the Society of St. John the Evangelist.”

Father Osborne agreed to stay on at the Advent for a few weeks, and then departed on the 28th of August, going first to Peekskill and thence to Philadelphia. In a letter to Father Grafton dated August 14th, Father Benson expressed, reluctantly, we may be confident, his willingness to release from their obligations to himself both Father Prescott and Father Walter Russell Gardner (who had been professed in 1880), in addition to releasing Father Grafton. Thus it came about that three Professed Fathers—Charles Chapman Grafton, Oliver Sherman Prescott, and Walter Russell Gardner—ceased to be members of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist.

This event in the history of the Society has been examined by many, and judgments have fluctuated all the way from those condemning the defection as an utterly contumacious breaking of the most solemn vows, to those estimating it as a justifiable parting of the ways in the face of genuinely conscientious difficulties. Father Hall, writing forty years after the incident, when he himself was no longer a member of the Society but a bishop, offered this consideration:

[28] “It should be remembered in judging the course of those who withdrew from the Society that no Constitution had then been agreed up—only the spiritual Rule; that there was at that time no to appeal to, nor any episcopal authority over Society as such, only over its individual members as priests. Hence in any difference that might arise as to conflict of duties and allegiance there was no possibility of an authoritative decision. Nor had any provision then been made for an honorable and religious release from obligations to the Society. As I have thought over the question lately, this has seemed a fair and right statement to make, where any is called for.”

That the separation was regrettable, and that it hampered mission of the Society in America are indisputable truths. In his book, A Journey Godward, Father Grafton states,

“Doubtless there were some misunderstandings on all sides; and I have felt that if I had been a holier man, my purpose would have been better understood, and the rupture might have been avoided.

Perhaps further comment upon what will ever remain a sad entry in the annals of the Society is unnecessary.

There still remained, of course, the practical problem of the Parish of the Advent and the church property. That invaluable source of information, A Sketch of the History of the Parish of the Advent, explains the solution of these remaining difficulties as follows:

“The corporation (i.e. of the Parish of the Advent), after looking into the matter, and realizing that the church in Bowdoin Street was, by the terms of its sale, set aside for the ultimate use of the Society of St. John the Evangelist, and was being occupied by the parish, in a sense on sufferance, promptly recognized the rector’s right to choose his own assistants, and at the same time acknowledged the position of the society by agreeing to finish the new church as early as practicable, and then resign the Bowdoin Street church to the uses of the society under the immediate charge of the assistant rector, with the understanding that he should resign his office in the parish, and conduct the work entirely independent of the parish. This arrangement was agreed on all sides as being, on the whole, the happiest solution of the difficulties in which the parish found itself.”

So calm descended after the storm, but for a time the familiar faces of Father Hall and Father Osborne were not seen within the precincts of the old church on Bowdoin Street.

XI. Peaceful Interludes in Canada

WHAT a contrast there was between that church on Bowdoin Street, Boston, and the settings in which Father Hall and Father Sheppard now found themselves. Mess-halls, saw mills, boardinghouse rooms, the area encircling an outdoor log-fire, [28/29] yes, even a saloon—these were the backgrounds in which the Fathers attempted to reach the hearts of railway workers along the Fraser River in British Columbia. Those remarkable letters of Father Hall to his mother and to the Father Superior at Cowley reveal the souls of men who spared no pains to minister to their fellowmen. The Fathers found shelter where they could, sometimes living in tents. They were frequently cold and wet, often dog-tired, as they trudged along the hazardous, muddy trails from camp to camp along the route which was to be followed by the new railroad. Sometimes there was little response among those who had embraced skepticism and infidelity. Father Sheppard once wrote to the Father Superior,

“Some of them seemed to think themselves out of the pale of religion altogether.”

But after a month of arduous, loving toil Father Hall could write to Father Benson,

“Now I think the work has the respect if not the sympathy of nearly all.”

In October the Fathers left British Columbia returning to San Francisco by ship. On their way through that city in July, they had hoped to see Chinatown but lacked opportunity. Now, however, accompanied by a policeman, they thoroughly inspected that fascinating section of San Francisco—the opium dens, pawnshops, sweat shops, jewellers shops, the Chinese theatre, the Joss House, and a restaurant. In his descriptive letter about this tour Father Sheppard wrote to Father Benson,

“I can’t give you any adequate idea of all the strange and sometimes appalling sights we saw—the dens of filth, and horrible abodes of vice—the dark holes and alleys we penetrated, the dreadful smells which assailed us; these must be personally experienced to be realized. But it certainly makes one feel what a joyless, oppressive thing life is without Christian hope and love, and how completely the vast multitudes of China are under the power of the prince of this world, being as they are without hope and without God in the world.”

It was to be a good many years after the writing of this letter before a Cowley Father was to become a participant in China’s warfare against the Prince of this World.

Leaving San Francisco, the Fathers moved eastward to Pueblo, Colorado, where they parted. Father Hall travelling northward to Denver to preach and deliver addresses almost continually for three or four full days. In Kansas City the Fathers again joined forces to conduct a mission at St. Mary’s Church. The mission ended on the 16th of November, and Father Hall proceeded to Philadelphia where he resided at St. Clement’s with Fathers Maturin, Osborne, [29/31] and Field, until the dust stirred up by the recent controversy in Boston, had settled and he and Father Osborne could return to re-establish the work of the Society in that city.

The early part of 1883 found Father Osborne, not in Philadelphia, but on the opposite side of Canada from that on which Father Hall and Father Sheppard had labored. Father Osborne first conducted a mission at St. John, New Brunswick, and then entered upon a dangerous and an arduous journey to Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, where Father Benson, with Father O’Neill, had conducted a mission in August, 1871. Stormy weather detained Father Osborne at Cape Tormentine, New Brunswick, on the mainland, where he lodged in a disreputable inn. Referring to his first night at the inn Father Osborne wrote to Father Benson,

“That inn, I hardly know how to describe it. The little public house at the Iffley Road end of Marston Street, would be a palace beside it . . . We had no sleep for there was not one moment’s quiet in the house, and the storm raged all around outside.”

The next two nights were quieter, however, after Father Osborne launched a nocturnal raid upon the disturbers and we assume he slept. The journey from the Cape to Prince Edward Island required eight hours of navigation across open water and ice fields at eight degrees below zero. Father Osborne found the entire experience an exhilarating preparation for his labors—a ten-day mission at Charlottetown during sub-zero weather, preaching engagements, a children’s mission, and a mission for adults at St. Mary’s Church, Summerside. Writing about the Summerside mission in his letter to Cowley Father Osborne states,

“After that I expect to cross the ice again, and go down to Massachusetts for Passiontide.”

XII. THE CHURCH OF SAINT JOHN THE EVANGELIST OPENS ITS DOORS

AS Passiontide drew near and Father Osborne travelled southward to Boston, Father Hall and Brother Gilbert moved northward from Philadelphia and forces were joined once again on Bowdoin Street. The brethren now resided at Number 44 Temple Street in a house adjoining the rear of the church. (This residence later served as Saint Anne’s Convent until its demolition in 1953.) On Passion Sunday, March 11th, 1883, the Parish of the Advent worshipped for the last time in the church on Bowdoin Street. In the course of that week the building was formally turned over [31/21] to the Society of Saint John the Evangelist and on Thursday (March 15th) services were held for the first time in the new Church of the Advent on Brimmer Street. One of the Sisters of St. Margaret records,

“On the day before Palm Sunday, Mass was said in the Father’s private chapel, and their new house was blessed. On Palm Sunday, Father Hall came to the Sisters’ chapel at seven o’clock for the blessing and distribution of palms, but there was no Mass, everyone going to the first Mass at the Mission Church of the S.S.J.E., as the church on Bowdoin Street was henceforth called. The usual morning and evening services and afternoon Sunday School were held, but there was no choir until the first Sunday after Trinity, the music being congregational in the meantime.”

In his biography, Arthur C. A. Hall, Third Bishop of Vermont, Dean George Lynde Richardson comments,

“With this began what was perhaps the happiest and most productive period of Father Hall’s life. The little church in Bowdoin Street, shabby and unattractive, became the centre of vigorous activity. Friends rallied to its support, and in ten years it grew from a mere handful to report over eight hundred communicants, with four priests and the Sisters of Saint Margaret carrying on a wide and constant ministry which reached not only throughout the city of Boston, but into many of its suburbs. ‘Father Osborne and he were at St. John’s together,’ writes one who was closely related to the work at the time, ‘both so magnificent and so different, and we needed both to help us. Often they would give courses of sermons; one in the morning, and the other in the evening, and we used to say that Father Osborne showed us our sins and knocked us down in the ground in the dust in the morning; in the evening Father Hall would pick us all up, show us the road to Heaven, and send us on our way rejoicing.’ Saint John’s became a centre to which many penitents resorted regularly for confession, and many in perplexity and doubt turned thither for spiritual guidance and help.”

XIII. THE SAINT FROM READING GAOL

WHILE in the course of 1883 renewed spiritual power was being generated by Cowley Fathers in Boston, another member of the Society was launching a great movement in Philadelphia. The movement was the Guild of the Iron Cross. The founder of the movement was Father Charles Neale Field. Henry Bradford Washburn, Dean Emeritus of the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, once stated in a lecture on monasticism,

“In every religious order you will find a gardener, a scholar, and a saint.”

[33] Applying this generalization to the American Congregation of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist, one must conclude that there have been gardeners galore, no scholars, and one saint. Surely Father Field was that saint!

Ironically, the good Father was born in the unholy confines of a jail. Let is be explained at once, however, that he was not the son of a female criminal, but of the wife of the Reverend John Field, who built, and served as chaplain to, the model jail in Reading, England. Doubtless it was his father’s solicitude for the underdog which motivated Father Field’s love for all God’s children, especially the underprivileged. Long before people began talking extensively about social justice, social service, and the social gospel, Father Field and Father James Otis Sargent Huntington, the saintly founder of the Order of the Holy Cross, were carrying out these teachings—the former in Philadelphia, the latter in New York City.

One day in 1883 a group of twelve workingmen gathered together with Father Field in Philadelphia to determine what they could do for themselves and for others. Out of that conference issued the Guild of the Iron Cross. The Guild was in no way connected with any socialist or political organization. It was primarily a moral and religious movement, and its members were committed to endeavor earnestly to suppress in themselves and in others, in temperance, profanity, and impurity. The founder and the members of the Guild realized that religion was the central factor in life, but they went on to apply the tenets of the Faith to their daily work and to their social relationships. Thus the Guild inculcated the fundamental concept of the dignity and sanctification of labor, and of the brotherhood of all workingmen. It proposed to attempt to elevate the condition and increase the good qualities of all laboring men. Above all the Guild tried to unite capital and labor in a spirit of mutual understanding and goodwill. This was indeed a bold concept for the year 1883. Father Field journeyed far and wide preaching the message of his Guild, and in the course of time it numbered many thousands—bishops, priests, and laymen.

In our day of the standardized five-day week it is taken for granted that most workers are free on Saturday and Sunday. Furthermore child labor has been generally abolished. But it has not always been so. One cause which Father Field and his Guild zealously espoused was a Saturday half-holiday for working-boys. On a little printed sheet disseminated as part of the campaign. Father Field explained,

[35] “The Iron Cross considers it a religious duty to do all in its power to obtain the Saturday half-holiday for the boys, and to help them to keep it well. The Guild of the Iron Cross rejoiced in the victory of the car conductors, when their hours were shortened, and the Guild will always take the side of the oppressed. It will rejoice when all workers have a half-holiday on Saturday, and it will not rest until this has been obtained for its boys.”

But having obtained a Saturday half-holiday, many of the working lads lacked the financial wherewithal to leave the City for some wholesome recreation. To counteract this Father Field organized outings to the Philadelphia suburbs or the seashore, or excursions up and down the Delaware River. One half-holiday outing sponsored by the Guild saw three hundred excited boys assemble at the Broad Street Station for an outing at Glenolden. Out in the country Father Field passed out bats and balls, and soon games were in progress everywhere. A newspaperman who reported the outing wrote that cheers were given for Louis Douglass, the President of the Guild, and he adds,

“But the three cheers for Father Field made the usually quiet woods ring again.”

Perhaps it was the devoted ministry of Father Field, more than any other factor, which caused St. Clement’s to become known as “The Church of Those in Trouble”. It was his great missionary zeal, combined with the moving preaching of Father Maturin and Father Convers, which brought so many to Christ in Philadelphia. The good works performed in the parishes in Philadelphia and Boston, as well as the missions and retreats conducted by the Fathers in innumerable places, spread far and wide the good name of Father Benson and his brotherhood.

From the beginning up to this date, the Society had remained under the personal direction of the Father Founder, but now, eighteen years after being formally inaugurated, it was felt by many that the time had arrived to adopt a constitution. It will be recalled that Father Grafton and Father Prescott had agitated for a Constitution and had declared that the reason for their separation from the Society was what they considered needless delay in its formulation. Finally, during the Chapter of 1884 at Cowley, the Statutes and Rule of Life of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist were formally adopted. The historic event has been recorded in these words:

“In the afternoon of the Monday following the Chapter, September 22, 1884, the Rev. the Father Superior General with all the Members of the Society at that time in England waited upon the Lord Bishop of [35/36] Oxford at Cuddesdon. His Lordship received them in the Palace Chapel, and, after declaring his acceptance of the Office of Visitor to which he had been elected by the Chapter, gave his blessing to the Society collectively and individually laying his hands upon each one present. The books containing the Statutes and the Spiritual Rule as adopted by the Chapter and approved by the Bishop were then signed by each of the Professed Fathers kneeling at the steps of the Altar.”

Thus the Society of Saint John the Evangelist passed from a state of tutelage to the status of a democratic institution governed by a written Constitution.

Father Hall, who was present at the Chapter of 1884 as the Superior of the American Province, remained in England for a full year. He attended the Seabury Centennial in Aberdeen, and held a number of retreats. Father Hall was constantly in demand as a conductor of both retreats and missions. During the period he was connected with the church in Boston he gave no less than fifty-seven retreats and preached fourteen parochial missions.

On the trip to the United States in 1885, Father Hall was ac companied by Father Field. In a letter written to Father Benson near the end of the voyage Father Hall explained that they had travelled “intermediate”, and that he had “felt much less out of place than amid the luxuries of the saloon, which always seemed incongruous with our habit.” In his transcontinental trip in 1882, Father Hall experienced qualms of conscience about taking a sleeper (though the journey then necessitated nine days of travel), but finally decided it was justifiable on the grounds of prudence. No matter by what class Father Field crossed the Atlantic he always spent a good deal of time with the steerage passengers. To alleviate the trials of the people enduring the horrors of steerage travel during his trip to America in 1880, Father Field collected money, fruit, tobacco, papers, and books from the saloon passengers, and redistributed the articles to the members of his steerage “parish”. On this trip in 1885 it was a similar story. By this date Father Field also took advantage of the opportunity to present the program of his newly-organized Guild of the Iron Cross to the steerage passengers. He persuaded two saloon passengers. Lord Brabazon, the President of the Young Men’s Friendly Society, and Tom Hughes, the author of Tom Brown’s School Days, to address the passengers assembled on the steerage deck, and he himself spoke on “Temperance, Reverence and Purity”. Father Hall wrote,

“Father Field is a singularly able and ready missionary on board, and has devoted himself to the steerage people. On Sunday and Monday evenings we had a meeting on deck, with hymns and short informal [36/37] addresses. . . . Perhaps the most edifying exercise has been the ‘school’ which Father Field has held most mornings. You might see him seated on the deck surrounded by about a dozen children, whom he would catechize on Christian doctrines, beginning with our Lord’s life, to which sets of pictures, with which we were supplied for dis tribution, furnished a capital introduction. A crowd of older people gather round and receive instruction and edification.”

Is it any wonder that everyone loved Charles Neale Field? Is it surprising that even the hostile Bishop Stevens received the Father at once with full standing into his diocese?

XIV. SAINT AUGUSTINE’S MISSION IS STARTED IN BOSTON

AFTER his return to Boston in August, 1885, Father Hall continued to be afflicted with poor health as he had been during his year in England. Nevertheless, he faithfully pursued his duties, and even assumed additional burdens. During the winter of 1885 and 1886 he, worked incessantly and was constantly preaching in Boston during Lent. He managed to preach the Good Friday service at Trinity Church, New York; but it became obvious to all that he was sorely in need of a complete rest. Finally in July his doctor prescribed a sea voyage to Fayal in the Azores on a sailing vessel. The four-month respite turned out to be just the needed cure. Father Hall recommended the Azores as a suitable resort, not only for the restoration of physical health and strength, but as a healthy antidote for those Anglicans who see in Roman Catholicism the acme of perfection. In a letter to Father Benson he described in detail the low estate of the Roman Church in that area and added,

“The Azores, healthful for various physical complaints, would, I think, prove a very remedial climate for any one suffering from Roman fever.”

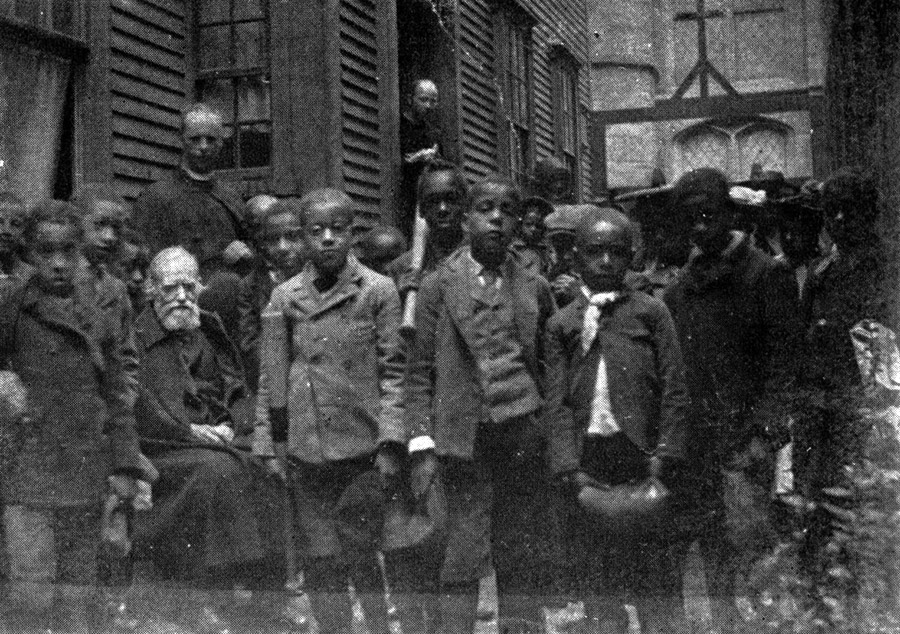

In his report to the Diocesan Convention of 1886, Father Hall expressed a desire that a permanent building might be secured for the rapidly-growing Mission of Saint Augustine for colored folk. In 1882, members of Saint John’s Guild of the Parish of the Advent (a Guild directed by Father Osborne) had opened a Sunday School on Phillips Street for negroes, but the project had been discontinued. Two years later, on February 17, 1884, another Sunday School was opened on Cambridge Street, most of the teachers being colored communicants of the Church of Saint John the Evangelist. Attendances increased rapidly, and in three-months-time a more adequate building on Anderson Street had to be rented. The school was first known as “Saint Phillip’s,” but in 1885 the name was altered to “Saint Augustine’s Mission.”

[38] A small Confirmation Class was presented to the Diocesan (Benjamin Henry Paddock) when he visited Saint Augustine’s Mission on February 23, 1886. This was perhaps the first time in the Diocese of Massachusetts that a Bishop had administered Confirmation in a church for colored people. In a letter to Father Benson written a short time after this historic occasion, Father Hall said,

“The Bishop’s visitation was on the eve of S. Matthias. It was his own proposal to come and pay us a visit—apart from any confirmation—if we could gather the people on a week-day. The Bishop first came to our School room at S. John’s, and made an address to the children of our Juvenile Branch of the Church Temperance Society at their Monthly Meeting. At S. Augustine’s we had semi-choral service, a shortened form of Evensong printed on a card, the intricacies of the Prayer Book being as yet beyond our powers, and then the Bishop preached extempore on the Parable of the Great Supper, and the different excuses which people make for neglecting the invitations of the Gospel. After this he Confirmed three persons, one man and two women, all married, and at the close of the service after disrobing he spoke to a number of the people individually, and said a few kind words of encouragement to the group of Sisters, especially on the blessedness of working where little immediate recompense is to be expected. The Chapel was full—the few white faces looking very white—and the people quite orderly and reverent, much more so than many congregations the Bishop must meet in his visitations.”

Writing to the Father Superior in September of the same year (1886), Father Osborne describes the Mission’s observance of its Patronal Festival. On that occasion the Reverend J. W. Elliott, and the Sisters of Saint Margaret took eighty small colored children in two horse-cars for a long ride through Brighton and Cambridge.

Father Osborne adds,

“They certainly created a sensation as they went along.”