____________ THE CHURCH HOUSE, WESTMINSTER, S.W. [1908] |

____________ THE CHURCH HOUSE, WESTMINSTER, S.W. [1908] |

THE cluster of islands which usually goes by the name of Santa Cruz really includes three distinct groups lying between Lat. 9º and 11º South, and Long. 165º and 169º East. These are, the Duff group--or to call them by its native name, Taumako--the Swallow or Reef group, and the three big islands of Santa Cruz (Ndeni), Utupua, Vanikolo. The Reef Islands are all quite small, the largest of them being not more than about four miles in length, while several of the smaller ones only contain a few acres. The Duff group has five small islands. Santa Cruz proper is a fair sized island, 22 miles in length, and 10 or 12 broad. They are very beautiful, and, like all the islands of Melanesia, covered with forest down to their very shores. There is no part of Melanesia more intensely full of interest than this, and the interest is of a threefold kind. Firstly, there is the interest which is attached to its romantic discovery; second, that which is excited by a study of the people themselves, their origin, customs and language; and lastly, there is that all absorbing interest, which will ever attract every loyal Churchman, in the story of the planting of the Church here--a planting which has been watered by the blood of the saintly Patteson.

Santa Cruz was first discovered by the famous Spaniard Alvaro de Mendaña, in the second of the two great voyages which he made from South America across the Pacific. On the first of these, in 1567, he found and named the Solomon Islands. In 1595 he set out a second time, with four ships, intending to re-visit the scene of his first discovery, but, getting into thick weather, he lost his bearings, and when the fog at last lifted, one vessel, the "Almiranta," had disappeared (it was never heard of again) and land was in sight.

Mendaña's first impression was that he had at length reached his destination, but on finding out his mistake, he named the new found land "Santa Cruz," and decided to establish a colony. At first the natives were well disposed to the strangers, but a mutiny broke out amongst the crew, and a friendly chief was murdered by the mutineers. This aroused the hostility of the natives, and in the midst of these troubles Mendaña sickened of fever and died.

After two months' settlement the colony was abandoned, and the Spaniards sailed away to the Philippines. Barely half of the illfated adventurers reached home. De Quiros, who had taken the command after Mendaña's death, made a voyage from Callao in 1605, and discovered Taumako, about 60 miles to the North East of Santa Cruz, and spent ten days there.

In 1766 an English vessel, the "Swallow," commanded by Captain Carteret, sailed round the Horn, and visited the Reefs, which he named after his ship. In 1797, Captain Wilson, commanding a mission vessel, the "Duff," touched at Taumako, and not knowing that the Spaniards had been there 200 years before him, he too gave to the group the name of his ship. At Vanikolo, nearly 60 miles to the South East of Santa Cruz, the great French voyager, La Perouse, lost his life. Such, briefly, is the romantic story of the discovery of these islands.

No less fascination attaches to a study of the people themselves. Some of the islands are inhabited by Melanesians, in others (a few of the Reefs and Taumako) there is a strong strain of Polynesian blood. The features give some evidence of this, while still stronger is the evidence afforded by their language, and the freer intercourse of the sexes. The habit of betel chewing which prevails everywhere connects the Cruzians with Northern Melanesia; there are, however, no powerful chiefs such as are found in the Solomons; in every village there are two or more headmen whose direct authority does not extend beyond that village, though their influence may do so. In the Solomons the canoes are plank-built, but here they are "dugouts" with an outrigger attached, as is the case in Southern Melanesia. The people are not cannibals, nor indeed have they ever been, with the exception perhaps of Vanikolo. The Polynesian customs of whitening the hair with lime, and the use of tumeric are universal.

Like other Melanesians the Cruzians have a belief in a supernatural power or influence, which is possessed to a greater degree by certain persons and things. This is called "Malete." It is "Malete" which enables a man to become rich or powerful. The ghosts of the "great" dead are invoked and their stocks set up in the ghost-house. Stones possessing this "Malete" are owned by some persons and are hired out by their fortunate possessors. At Te-Motu is a large stone called Kio (a bird) upon which offerings are made, to guard the newly planted gardens from the ravages of the bush fowls.

Cruzians have a strong belief in the hereafter, and ghosts of the dead go to Netepapa and thence, to be purified, into the volcano of Tinakula.

They are a hot-blooded excitable race and fighting is very prevalent. Peace can be secured by the payment of money in an ordinary case, but if the feud is a bitter one, it may last for years.

Two villages may have such a feud and an honourable peace can only be procured by handing over little boys, to be shot in cold blood by the aggrieved party as an equivalent for the lives lost in battle. In case of a row one may almost always say, with the cynical French monarch, "Cherchez la femme."

The native money is a curious coinage. It consists of a flat piece of rope, about 15 feet in length upon which the red breast feathers of a small bird are gummed. A man will spend days in the forest catching these birds, he covers himself with leaves and imitates their note, the victim is attracted, and settling on one of the twigs which has been smeared with bird lime, is easily taken. The hunter will return home with several of the birds, alive, tied to his belt. When the red feathers have been plucked the bird is released. The money is kept carefully coiled and covered up on the platform over the fireplace. A rich man will sometimes build a hut in the bush for his money. As the feathers wear off the money depreciates in value.

A Cruzian has few tools, a shell adze, a rude drill, a file made from the skin of the giant ray and a shark's tooth complete the list, and yet he is a wonderfully neat workman. From the fibre procured from the bark of a tree he makes fishing lines which are as tough as whipcord.

He is a vagabond by nature and seldom remains for long at home. For all his hot blood he is a warm-hearted, loveable fellow and dearly likes a joke. He is a pure creature of impulse and anything like discipline his soul abhors--what the Gospel can do for him has been shown in the lives of some of the converts. Benjamin Teilo, a Matema boy, who offered as missionary to Vanikolo is perhaps one of the brightest examples.

The history of the mission in Santa Cruz begins with the first visit of Bishop G. A. Selwyn in 1852; he did not, however, on that occasion think it wise to go ashore. Four years later he made a second visit to the district, and, at Santa Cruz, tried to make friends with the people. At Nukapu, in the Reefs, his knowledge of the Maori knowledge enabled him to make himself understood to some extent. Mr. Patteson was then with him and together they landed at Utupua; noticing, however, that the people were becoming excited they prudently beat a hasty retreat. Another landing was effected at Vanikolo; where they found 60 skulls, grim evidences of the sad fate which had befallen La Perouse and his crew.

In 1862 Patteson, who had been consecrated to be first Bishop of Melanesia, went ashore at seven different places on Santa Cruz--being the first white man to do so since Mendaña's day. He was everywhere well received.

In 1864 this good beginning received a serious set back. Encouraged by his previous visit the Bishop went ashore in Graciosa Bay, but as he was about to re-embark the natives suddenly fired upon the boat. Three men were wounded by the arrows, and two of these, Edwin Nobbs and Fisher Young, died a few days after, in great agony, of tetanus. For a number of years it was useless to risk a call at the island, but in 1870 the Bishop landed at Nukapu, where the name of the great Selwyn was remembered with affection. In 1871 Patteson made his last voyage, and September 16th found his vessel in sight of the district. Since his last visit an outrage had been committed in the group by the crew of one of the "labour" vessels which in those days were no better than "slavers." There was at that time no government official on board to see that natives who wished to leave their homes for the sugar plantations of Fiji were fairly dealt with. These vessels were too often in charge of an unprincipled ruffian who employed both force and cunning in abducting the natives. One of these vessels had lately visited Nukapu and carried off by force five of its people. There is a story that the captain beguiled the men on board under the pretence that their friend the Bishop was there. However that may be the deed was done and it left a thirst for revenge which was soon to be so fatally gratified. Patteson had heard rumours of this outrage, and it was with the full consciousness that he was risking his life that he visited Santa Cruz for the last time.

The Southern Cross of those days was not, as now, a fine steamer, but a sailing vessel, and with light winds made but slow progress. On the 18th they were off Tinakula, a volcanic cone which rises over 2,000 feet, and at night presents a grand sight. Patteson, in a letter home, written the same day, comments upon "its masses of fire and tons of rock cast into the sea." Next day he addressed his boys as usual at evensong, his subject being the death of Stephen. On the morning of the 20th they reached Nukapu. A few canoes were off the reef, which runs out two miles enclosing a large lagoon. The tide was too low for the boat and so the Bishop left it to wait for him outside the reef while he went ashore in a canoe. His friends saw the canoe reach the shore, saw Patteson walk up the coral beach and enter the clubhouse--and that was the last time he was seen alive. What happened then is to a certain extent conjecture, for native accounts do not always agree. This at least can be gathered: the Bishop lay down in the hut, his head resting on a wooden pillow, and while in that position he was killed outright by a blow on the head, dealt from behind, with a short wooden club, used for beating out bark cloth. Shouts at once went up from the people on shore, and simultaneously the men in the canoes shot at those in the boat. The Rev. J. Atkin and two native Christians were wounded and the boat was rowed back to the ship. Shortly after, two canoes were seen to leave the shore, and when well out in the lagoon, one of them returned. The remaining canoe carried the Bishop's body. Upon it lay a coconut frond tied in five knots and on the breast of the body were five arrow wounds--a like number marked the body of his crucified Master--made after death. These bore silent witness that for the five natives abducted by the labour-ship, vengeance had been taken. Mr. Atkin, and Stephen, one of the two natives who were wounded, died by tetanus a few days after.

In 1875 another white man laid down his life on these islands. Commodore James Goodenough, a warm friend of the mission and a noble type of Christian gentlemen, was shot at Carlisle Bay, Santa Cruz, whilst trying to prove to the natives that he was their friend.

Two fine metal crosses now mark the sites of both martyrdoms.

All hope of gaining a footing in Santa Cruz seemed now indefinitely postponed, but a door was soon to be opened. In 1877 a big canoe from Nufiloli was blown out of its course to Port Adam in the Solomons, 160 miles distant and Bishop John Selwyn (who had succeeded Patteson as Bishop) learned that two of its crew were being kept and fattened for a cannibal feast. After considerable difficulty and no little personal risk he succeeded in buying one of the captives and took him back in triumph to his home. Thus in the Providence of God a way was made at last and Christianity found a footing in Santa Cruz. Wadrokal, a native of the Loyalty Islands, offered himself as a teacher, and his offer was gladly accepted. Since that year, 1878, Christianity has had many vicissitudes in the district. The gross superstition of the people, the great difficulties of the languages, the break-down in health of more than one white missionary in charge, and another sad cause has militated against such rapid progress as has been achieved in other parts of the diocese. Christianity has brought much change for the better. Everywhere the missionary is now regarded as a friend. There is a weakening of the old superstitions and the humanizing and civilising influence of the gospel has been proved even though the Church is as yet numerically weak.

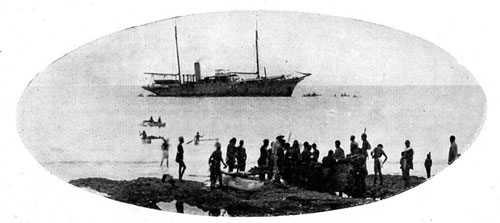

CANOES AROUND "THE SOUTHERN CROSS." THIS picture gives a capital representation of what takes place when The Southern Cross is off Santa Cruz. Directly the vessel is sighted by the natives, excitement prevails on shore; everyone hurriedly seeks for something which he can barter for tobacco which he loves so well, or in the hope of obtaining calico for a new loin cloth: fowls, coconuts, bunches of bananas, mats, bags, etc., are placed on the canoe, together with the bows and arrows, without which a Cruzian would never feel safe, and the canoe is carried down the shore and launched. This requires considerable skill, the waves are rolling in and breaking in the white foam on the coral beach, the men wade into the sea and seizing their opportunity, immediately after a big breaker has spent itself, they spring into the canoe and paddle for dear life to get well away ere the next breaker has time to meet them. The body of the canoe is a log hollowed out with a shell adze:--to this an outrigger is attached to steady it, and on this the goods are placed. The outrigger is always on the lee side. A missionary at Santa Cruz does most of his coastal travelling in one of these canoes. By the time The Southern Cross has arrived she is surrounded by scores of these canoes all full of eager salesmen; all are gesticulating and shouting, holding up their wares with one hand, while the number of extended fingers on the other indicates how many sticks of tobacco they demand. The Cruzian is a keen bargainer, and will begin by asking far more than he expects to get. When the Ship comes to anchor, or even before, if a rope be thrown to them, the natives clamber up her sides, and the decks are soon covered with a merry, noisy crowd, who press their wares upon you and will scarcely take a refusal. All cabin doors are locked and port holes closed, for the Cruzians are born thieves, and exceedingly clever ones; though their only garment is a loin cloth, and they have no way of hiding their plunder save in a small bag which they carry, yet frequently they manage to steal without detection. Our late skipper, on retiring to rest after a visit at Te-Motu, discovered that his pyjama jacket had mysteriously vanished! When the Ship moves off it is with difficulty that the natives can be induced to leave her; one or two hold on to the last in the hope of a final bargain, and then jump into the sea to swim to shore with one hand, while with the other the property is held up out of the reach of the sea water.

That night round the clubhouse fire the bargains are related amidst much laughter and chewing of betel nut.

NAMU, SANTA CRUZ. NAMU in Graciosa Bay is the new Headquarters for this district. It is a much more suitable one than Te-Motu, here there is no surf to contend with and there is an excellent anchorage. A good wooden house has been built, and stream close by furnishes what was sadly needed at Te-Motu i.e. a good supply of fresh water. The missionary's boat is on the shore; most of his travelling is done in it, and about 30 miles of open sea have at times to be traversed.

The weather needs to be watched and a favourable wind taken advantage of; it is no joke to be caught by a squall in an open boat. There is a tremendous "set" to the west in this part of the ocean, and should the wind drop, rowing is very slow and laborious work. To be becalmed under the fierce blaze of a tropical sun is a trying experience and generally entails an attack of malarial fever. In crossing from the "Reefs" to Santa Cruz one is guided by the mountains which rise grandly some 3000 feet, but if voyaging the reverse way, one sees nothing but open sea until within a few miles of the lowlying "Reefs." On approaching the surf the sails and mast are lowered, the rudder taken off and a long steer-oar substituted for it (see the illustration). To pass through a surf is at first an alarming experience, but one soon learns the art of keeping the boat straight by means of the steer-oar, and, provided the surf be not too formidable, the experience is an exhilarating one. Graciosa is of course a Spanish name, and it is probable that Mendaña's settlement was in this bay. The missionary in charge stands in the foreground of the picture--notice his dress! a serviceable helmet (to protect and neck and head), flannel shirt, khaki trousers and strong canvas shoes; the trousers are rolled up for he has only just landed; it would be rash however to leave them thus for long, so great is the power of a tropical sun that a very short exposure would inevitably result in considerable pain and swelling. There is a certain amount of risk and hardship attached to the boating work; will friends bear this in mind when the petition goes up "for all those who travel. . . . by water"?

It is a wise arrangement that the missionary should have one comfortable home in his district for which he can make when fever has pulled down his strength. To lie in a native hut--perhaps on the ground--under such conditions does not conduce to a rapid recovery of one's health.

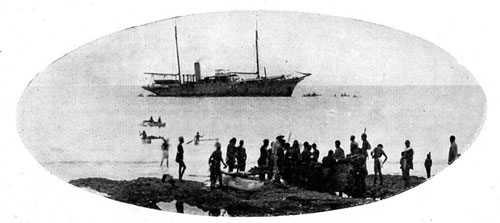

NIBI--A NEW SCHOOL VILLAGE. TREVANION Island, which is only separated from the big island of Santa Cruz by a narrow strait, has two native names--one side being called Te-Motu, the other Nibi (Anglicé Nimbi). There has been a school on the Te-Motu side for many years, but until quite lately the Nibi folk steadily refused to receive a teacher, or give us a boy for Norfolk Island. Many visits were made by the Missionary in charge, and he was always received as a friend, but there it ended. One day four Nibi men came over to the Te-Motu School Village; two of them had very bad sores, and they were persuaded to stay for a time to have them properly dressed and attended to. The sores healed, and the grateful patients returned home to send others similarly afflicted. Quite a little crowd of fresh patients arrived, and when the Southern Cross next called she was taken round to the Nibi side, with the happy result that at last the wall of prejudice was broken down, and five boys were obtained for Norfolk Island. One of these boys, Edward Pore, is now a teacher among his own people, and ere long doubtless the first-fruits of the Nibi harvest will be gathered in. Nibi is one of the most beautiful spots in the district; from the cliffs which overlook the strait one may look across at Santa Cruz, while the waters between present many varieties of blue, from a rich deep azure to that milky shade which warns the sailor of the dangerous coral reef below. Some twenty years ago, a severe earthquake altered this coast, a large piece of the island sank and let in the sea, forming a little bay--this is quite shallow, and the stumps of a few palms may still be seen sticking up from its waters. The centre of the island is probably an old crater--it is very fertile and great quantities of yams are grown here.

The round white ornaments worn by some of the natives denote high rank. The old man on the left side of the picture is carrying his little boy on his back; boy babies are nursed by their fathers, but girls are left in the mother's care. The man on his left has many pieces of bark cloth wrapped around his head--a woman's dress is generally a piece of such cloth. Notice the long hair of the man near to him; heathen often allow their hair to grow to great length; it is whitened with lime, the temples are shaved; sometimes one sees extraordinary coiffures, one side of the head will be reddened with tumeric, the other limed. A small boy's head is often shaved with the exception of a tuft or a fringe, or one long curl is allowed to hang from the forehead.

ROUND HOUSES, SANTA CRUZ. WHEN the Spaniards discovered Santa Cruz they remarked upon the unusual shape of the native huts; with the exception of the clubhouse ("madai") they are usually round, not unlike a beehive. The low walls are sometimes made of slabs of wood hewn out with great labour, but more often they are simply thatched, like the roof, with leaves of the sago palm, or, in the small Reef Islands, of the coconut palm. A chunk of a particular kind of coral crowns the top of the hut and coral slabs encircle the hut to keep out rain water. There is only one door, and to enter it one must bend almost double; the object in having it so low is to prevent the sunlight from entering, and thus to keep the hut cool. The huts are so close together that there is only just room to walk between. In a large village it is quite puzzling to find one's way, each hut being so like its neighbour. Within the hut there is barely room to stand upright, for in the centre stands a large platform on four massive posts about five feet high: on this the food is stored to preserve it from the rats which abound, one may see processions of them on the bamboo framework of the hut. In the house of a great man the posts are elaborately carved.

Beneath the platform is the fireplace and the smoke finds its way out as best it can; the thatched roof is blackened by it and thus preserved from the ravages of damp. A native church roof has but a short life, about five years, and needs continual attention; but a hut roof will last for many years.

The married people and children only inhabit these huts, the unmarried men and lads occupy the clubhouse, which generally stands a little distance apart. The dead are buried within the hut close to the fireplace. After a time the body is exhumed, some bones are used for making arrowheads, the skull is placed in a basket and kept. When a death has occurred friends and relatives assemble and make a "great lamentation"; these expect to be paid with money and food. The death song is a weird and depressing one and goes on continuously. A man will enter the hut and join in this, tears will pour down his cheeks; suddenly he will rise up and adjourn to the clubhouse for a rest, and will laugh and joke and chew betel nut, then he will return to the hut and once more shed torrents of tears with apparently little effort.

In Christian villages one of the first reforms is to set apart a piece of ground for a cemetery and the professional weeping gradually dies out.

HEADMEN IN A SANTA CRUZ VILLAGE. THIS group of Cruzians is a very typical one. To be photographed however is a serious matter all the world over, and one feels that the artist might have said with advantage "just a little pleasanter!" Each man is wearing his turtle shell nose ring. The armlets depicted are made of bark string and shell beads--for a dance a man would also wear eight to ten shell armlets. Notice how the pipe is carried. The cloth wrapping round the wrist is for a protection against the chafing action of the bow string. A Cruzian generally shaves his temples and head. In the old days his razor was a shark's tooth, or the hair would be pulled out by the roots, two small shells being used as tweezers, both very slow and painful processes. Nowadays a native will beg an old bottle and effect an "easy shave" with a fragment of it. The nose and ears are bored in infancy, and by a system of plugging the lobe of the latter is gradually enlarged.

Small boys cannot don their ornaments or loin mat until pigs have been paid, and the latter is not usually put on until the 12th or 13th year. The man on the left is holding his bow. The piece of cane in the hair is used as a comb. Pigs, dogs and rats are the only animals found in these islands; the dogs are miserable mongrels, and of necessity vegetarians or nearly so. Scarcely any event takes place in the life of a native without a ceremonial killing of the pig. At conception, birth, death, the putting on of ornaments, obtaining a wife, building a house or canoe, and settling of disputes, pigs are paid. The villages are surrounded by a stone wall to keep them out, but piggy will often manage to make a breach and effect an entrance. The writer was once aroused from his slumbers, in a club house, by something pushing against him--it proved to be a pig! When a man has eaten his meal he will carefully collect the scraps in a bag and going into the bush call "Poi Poi!" The pig knows his master's voice and scampers to him to be fed. A pig's ears will sometimes be bored and an earring or piece of red calico attached.

Gardens must be carefully walled against them, and it is a recognised law that an intruder may be shot and eaten. At Santa Cruz pigs are usually drowned in the sea; in the Reefs they were (and the custom still obtains in parts) killed by being suspended over a big fire. "Surely the dark places of the earth are full of the habitations of cruelty." Even where Christianity is not yet received its leaven is at working making such barbarous customs to disappear.

MAT MAKING. THE Cruzians are deservedly famous for the beautiful mats and bags which they make. The fibre used in these is obtained from the succulent stem of the Banana plant; a stem is laid upon a slab of wood and beaten to a pulp with a heavy piece of wood; the vegetable matter is then scraped away and the fibre hung up to dry in the sun, it is then combed out and is ready for use. But a Cruzian does not plait his mats (like other Melanesians), he has a wonderful loom--how it comes to pass that the loom is found only at Santa Cruz in the whole of Melanesia no one can say, the nearest locality where a loom is used seems to be the Caroline Islands which are about 1,000 miles distant. The native tradition is that it was invented by a woman, but insomuch that it kept her from the less interesting and more arduous labour in the gardens, the invention was appropriated by her lord and master. Canoes, driven away by contrary weather, or impelled by the pure spirit of adventure, have travelled extraordinary distances in the Pacific, and it is possible that in this manner the loom first found its way to Santa Cruz. Its existence was remarked upon by the Spaniards in 1595, so that the puzzle is little likely to be solved now.

The fibre of a black-stemmed banana is used for working patterns in the mats and bags. Such a mat as that in the illustration would be worn by the wife or daughter of a man of high rank; a narrower mat is the men's sole dress, and is worn like an apron "fore and aft," being held in position by a belt which may be made simply of a piece of bark, or plaited string or split cane, sometimes a purely ornamental belt of shell is also worn, or one of banana fibre elaborately worked.

The bags, which every Cruzian wears slung around his neck are also made on this loom, and bands for binding a man's long hair when he is sailing his big canoe.

The mat on which the man is sitting is made of plaited coconut leaves, and is used for covering the floors of the huts. The banana plant may be seen in the background.

The man's hair is decorated with "Mini," a pungent yellow-leaved shrub, of which natives are very fond. It is greatly to be feared that the art of working with the loom is likely to die out ere many years have passed. When the native can obtain calico for his loin cloth he will not trouble to make these beautiful mats.

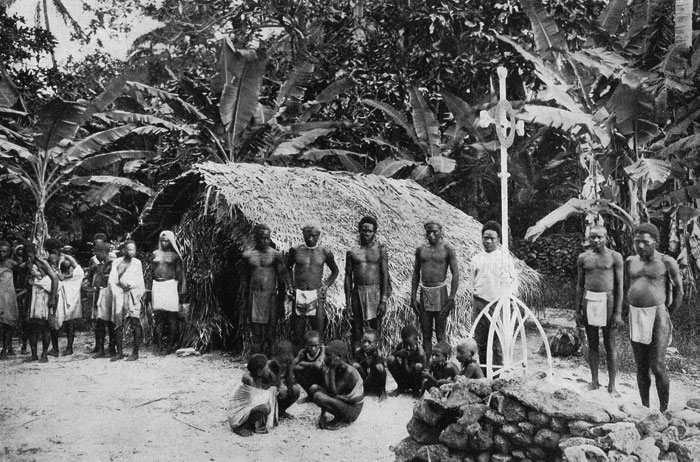

A GHOST-HOUSE. IN every village in the Santa Cruz district three is a ghost-house ("Maduka"), sometimes it stands close to the Madai, within the village, sometimes it is built outside the village wall, a little apart in the bush. In one place it may be a fine spacious building with massive posts and beams, in another a poorly built hut. A ghost-house on the Te-Motu shore has its beams elaborately carved, the centre one representing a shark. The walls are covered with paintings in white, red, and black; the ghosts are represented as being engaged in shooting, fishing, making canoes, etc., and the ubiquitous pig features conspicuously--some ghosts are even represented as enjoying a pipe.

The ghost-house at Nupani in the Reef Islands is an especially fine building. At one side of every ghost-house are a number of wooden stocks or posts of various sizes[;] the upper half of these is quaintly carved and the whole is smeared with lime; black patterns are painted upon them; sometimes a fish, or the frigate bird is drawn; a band of dried coconut leaves is tied around the centre. These posts are called "Duka"; the same word is used for a ghost, and each post represents the ghost of some great person who is dead and who in his life time was especially rich or strong or skilful. His power while he lived was supposed to prove clearly that he possessed "Malete" to a great degree, and now that he is dead his ghost may be invoked. Some posts represent female ghosts and some those of children. One may often see offerings of food or money placed before these posts and sometimes a native kneeling--yet there does not seem to be much sense of reverence for the ghosts. The writer has seen a number of natives in the ghost-house at Nupani lying on their backs chewing betel nut, laughing and joking, while another was taking a siesta.

On the big island of Santa Cruz a ghost-house seems to command more respect.

It must not be supposed that these posts are in any sense idols, they are memorials, nothing more.

Certain men are supposed to have special power with particular ghost, such a man is a "Meduka," and others will, with offerings of money or pigs, induce him to invoke it on their behalf. Sometimes a "Duka" will be taken on a voyage with a view to securing favourable weather during the trip.

A DANCING GROUND. LIKE all Melanesians the Cruzians are devoted to dancing. In every village you may see one or more circular spaces, enclosed by a rough wall of coral rocks, within which the ground is smooth and hard; this is the dancing ground. A moonlight night is generally chosen for the occasion. The dance begins about sunset and continues until sunrise--dancers retire every now and then to partake of the feast which is always provided, and to chew betel nut--a dance will often last several days. The men get themselves up for it with as much care as would a young English girl for her first ball. The hair is carefully combed out with a piece of cane and limed. (It is a common sight beforehand to see a big fellow lying on his chest while another squats beside him and plays the part of hairdresser). The best loin mat is put on and the full complement of shell armlets and earrings; occasionally the nose ring is exchanged for a large ornament of mother-of-pearl. Bunches of the strong smelling "Mini" are stuck in the belt and armlets. There are many different dances, but one feature is common to all, namely, a vigorous stamping of the feet upon the hard ground, the noise a man can make in this way is surprisingly loud, and all the while a nasal and most unmusical song is going on. At some dances clubs are carried--clubs are only used at dances, never for fighting--the upper part of these is carved to resemble a fish, and the whole is smeared with lime, and patterns drawn in red and black. A number of large nut shells strung together are attached to the handle and a string of them tied round the ankles, these help the discordance. At other dances bows and arrows are carried, while at others again the hands are free and are struck together with resounding claps at intervals.

At one dance a large fan palm leaf is worn in the belt at a man's back and the effect is grotesque indeed. Women hold their dances by themselves, but are, on occasions, permitted to follow the men walking on their hands and feet! At these times they will adopt the nose ornament worn by the men in the Torres Islands, i.e. a stick made of clam shell. An inspiration will sometimes come to a native who will produce a new song for a great dance. These songs are often conducted by a leader, while two parties of singers will take up the refrain antiphonally. Both songs and dances are for the most part quite innocent, one or two however the Christians have tabooed as being indecent.

The dancing ground in the picture is at Pileni and the building in the background is the school.

A 'TEPUKEI,' OR SAILING CANOE. THERE are no bolder semen or finer swimmers in the whole of Melanesia than in this district. In addition to the small canoe which has already been described, the Cruzians construct large ones for sailing. The best builders, they themselves tell us, are the people of Taumako, and the Matema people have the reputation of being the most skilful and fearless sailors. The Tepukei is made upon the same principle as the small canoe, but the hollow log is caulked and acts as a float to support the big stage or deck--on the stage is a hut in which the voyagers can take refuge from the heat of the sun. The wind is caught by means of a lofty and strikingly shaped sail, which is plaited by the women (the Papuans use two similar sails for their big canoes), and the steersman uses a long paddle. Voyages are made as far as Vanikolo, and Tepukeis have been even known to make their way to the Solomon Islands. At night they steer by the stars. Should the canoe be caught by foul weather, the clumsy craft is soon broken up, and men will, when they have lost all hope of making land again, shoot one another with their bone-tipped arrows. When beached, the Tepukei is carefully covered with coconut mats (a small canoe is turned upside down). To pull a Tepukei up a steep beach is a laborious task and requires many hands; like our own deep-sea sailors, they sing as they pull.

The following account of the building of a canoe was given by a Cruzian--"Only some men may dig out canoes--those whose ancestors dug them out. When a father is near death, that father takes water and washes his son's hands, and they think that the father is giving to his son understanding and wisdom to make canoes, and he signifies it through water. When a man has finished a canoe he takes it down to the sea and paddles very far, and makes it roll on the surf, and thus he thinks that he drives away the ghost from the adze with which he dug out the canoe, and the ghost of the spot where he cut down the wood for the canoe."

A Cruzian is as much at home in the water as on dry land; he loves the sea, and takes a dip morning and evening: a favourite amusement is to make a surfboard, and lying on it, to allow oneself to be carried in to the shore on the crest of a billow. A man will teach his little son to swim as soon as he can toddle, and it is a pretty sight to see a swarm of youngsters step fearlessly up to the surf, dive under it and swim and float and tread water together.

MATEMA--THE SCHOOL. MATEMA is one of the smallest of the Reef Islands and is generally the point which one makes for in a boat journey from Santa Cruz. Like all the Reef Islands, with the exception of two, it is only just above the high water mark; it lies on the edge of a long reef which extends for miles and which is bare at low tide. The inhabitants have no gardens and subsist on fish (of which there is a bountiful supply), coco and other oils nuts and breadfruit. When they wish for a change of diet they make a voyage to Santa Cruz and barter mats for yams--the Matema men are famed for their bold seamanship, and in their big canoes make periodical visits to Utupua and Vanikolo, the latter of which is fully 70 miles distant. When the tide is coming in the men wade out armed with hand nets, as soon as a small shoal is seen a cry is raised and with a dash it is surrounded; the circle grows smaller and smaller, and as the fish attempt to break through the cordon which has been drawn around them they are taken in the nets. When a man has caught a fish he takes it out of the net, kills it with a bite at the back of the head and throws it over his shoulder, the boys, who are ready waiting, seize it and thread a piece of cane grass through its gills. When a sufficient quantity has been secured the sport is over, and the booty is broiled over a fire of sticks for the day's meal.

When there is a plentiful bread-fruit harvest a pit is dug and lined with banana leaves; in this the fruit is placed and a kind of ensilage made. The pit is covered over with banana leaves and a wall is built to protect it from the pigs. When food is scarce the silo is opened and the odoriferous mash greedily devoured.

A good many years ago the Matema people gave us a boy, Andrew Veleio, who after his confirmation settled down as a teacher among his own people and built the school which is shown in the picture. Superstition, however, was very strong, and little headway made for years. The next boy who was sent to Norfolk Island returned home to die of consumption, and his death was attributed by the people to the fact that he had taken some coconuts from a tree upon which a "tapu" had been laid. Their confidence in us, however, remained unshaken, and, although his sister met a similar fate shortly after her return home, they still continue to give us scholars, and one, a brother of Andrew's, has gone as a missionary to the distant island of Vanikolo where he is doing good work.

THE SCHOOL AT NUKAPU WITH BISHOP WILSON. NUPANI, the Ultima Thule of the Reef group, lies over 30 miles to the west of Pileni. About half-way between the two is the islet of Nukapu, so insignificant in size, yet so famous in the history of the Melanesian Mission, as the scene of Patteson's martyrdom. Like several of the other Reef Islands the inhabitants have a strong strain of Polynesian blood in their veins. They have traditions of canoes coming thither from "Tongoa," which is probably "Tonga" in the Cook Islands. One such story tells how a large canoe, filled with "very tall men," landed on a dark, stormy night, and how the natives lay in ambush and murdered a number of them. Of those who were left, a few re-embarked and escaped with their lives, while others fled into the bush and dug a big hole and lived there. The story, no doubt, contains a substratum of fact. The big hole is still pointed out; while the language and features of the Nukapuans both testify to the fact that Polynesians must at some time have visited the island.

A school has now been built a Nukapu and boys are freely entrusted to us for the Training College at Norfolk Island.

The district of Santa Cruz is at present (1908) without a Missionary. Its area is far too wide for one man to work alone; from Taumako to Vanikolo is 117 miles, from Vanikolo to Nupani 128 miles. Special difficulties attach to the work here, and the Missionary is the only white man in this group of islands. Will not two missionary-hearted men with health and strength respond to the cry from Santa Cruz and Nukapu, "Come over and help us"?

Our last picture shews the School at Nukapu with Bishop Wilson and some of the school people: the first one, the Patteson Memorial Cross, upon which are the words:--

In Memory of

JOHN COLERIDGE PATTESON, D.D.

Missionary Bishop

Whose life was here taken by men, for whose sake

He would willingly have given it,

September 20th, 1871.All communications respecting the Mission should be addressed to the Secretary, and contributions remitted to the Treasurer, Melanesian Mission, Church House, Westminster, S.W.

Geo. Pulman & Sons, Ltd.,

London and Wealdstone.