|

______________________ |

[2] Letters concerning Mission Work, &c. Should be addressed to the Secretary:--

BISHOP SELWYN,

THE LODGE,

SELWYN COLLEGE,

CAMBRIDGE.Subscriptions, Donations and Offertories to the Treasurer:--

Rev. W. SELWYN,

BROMFIELD VICARAGE,

SHROPSHIRE, R.S.OOrders and Subscriptions for Occasional Papers to:--

Mr. PARTRIDGE,

PRINTER

LUDLOW.Subscriptions and information concerning the Island Scheme, to:--

MISS WILSON,

GLEN HOLM,

SOUTHBOROUGH,

TUNBRIDGE WELLS.

The Secretary hopes that the friends of the Mission will make a note of the persons to whom to send their various subscriptions. If sent to him, he has to write two letters, and the Treasurers have also to acknowledge the receipt to him and to the Donors, thus necessitating four letters instead of one.

[3] Communications respecting the Mission are requested to be made--

In ENGLAND, to the

Rev. Wm. Selwyn, (Treasurer),

Bromfield Vicarage, R.S.O., Shropshire;Or to the

Right Rev. Bishop Selwyn, (Secretary),

Master's Lodge, Selwyn College, Cambridge.In NEW ZEALAND, to the

Ven. Archdeacon Dudley,

Auckland.In NEW SOUTH WALES, to the

Rev. H. Wallace Mort, M.A.,

All Saints', Woolahra, Sydney.In VICTORIA, to

W. T. Lazenby, Esq.,

Sapleton, Caroline Street, South Yarra, Melbourne.In SOUTH AUSTRALIA, to

Augustus Stürcke, Esq.,

Church Office, Adelaide.In QUEENSLAND, to the

Rev. Canon David.

Bishopsbourne, Milton, Brisbane.In TASMANIA, to the

Ven. Archdeacon Hales,

Launceston.In WESTERN AUSTRALIA, to the

Right Rev. The Bishop of Perth.

The Southern Cross,

Dip Point, New Hebrides,

September 5th, 1896.My dear Bishop,

You know the pleasure of sailing with a good breeze past the Dip, on the way back to Norfolk Island. I am just enjoying that pleasure now. The only drawback to it is that we have burnt 50 tons of coal on the voyage, and we are still steaming with sails set, and there is every prospect of our wanting more coal. Our coal bills get heavier every year as the work grows, and we have to make faster voyages. We shall probably put in to Vila and get 20 tons, to make sure of reaching Auckland in reasonable time. The outlook with all its clouds is fairly bright. I know very little about Bugotu, as I have scarcely seen Welchman. In Gela the Church is doing well generally, and shewing its life by a desire to get hold of Guadalcanar. I believe there is a real wish to do something for these close relations of theirs. An attempt was made by Ellison Gura, He said he had received a letter from the Chief at Tetere, near Tasiboko, asking him to go over and teach his people until a boy now at Norfolk Island of his own tribe (Gabata) could go and become their teacher. I suggested that it might be wiser for him to go in a Gela canoe than in our ship, which might frighten them, but he said he had no fears, as they were so much his friends. He gladly left his all at Nago, and we took him across to Tetera. The chief came alongside, dressed as an Austrian Blue Jacket. Ellison told him that he had come to start a school, as requested. The chief was terrified, and said that now he would have to give up everything he liked. The people on shore showed less desire still to have a school, and in two days poor Ellison saw that it was useless to stay any longer. The people were preparing to leave the village because of him. Woodford, the Deputy Governor, arrived in Nielson's schooner, and saw that there was trouble, and very kindly brought Ellison back to Gela. George Basile, Hugo Gorovako, and David (a returned labourer we had at Norfolk Island) are doing very well at Vaturanga, at the south end of Guadalcanar, and if news of the misfortune at Tetere does not disturb their relations with the natives, they will probably build a Christian village on the sea shore facing Savo next summer. These boys are really doing splendidly. They are some of the best Christians I have ever seen.

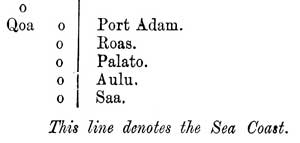

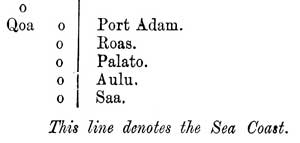

In Mala, Ivens has settled down at Saa, and is very happy. The heathen are letting the Christians alone, and there is no doubt but that the faith is spreading. School villages in Malo lie in this order:--

Takai, the chief at Port Adam, is quite a young man, but has done some nasty things in his time. Last year he came to Norfolk Island to see the place. He picked up a good deal of Mota, and a strong desire to be a Christian. He is now attending a Baptism class, and next year perhaps he will be baptized. He is a nice young fellow, but a shameless beggar. Before I reached his village he managed to make a letter reach me, asking me for a belt, a black dog, a knife, some hooks, and (in the postscript) a gun. When I saw him he asked me for some cloth and tobacco. It is his nature to ask, and I don't think he expects to receive. But with his faults I believe he is genuinely fond of us. He keeps his people quiet, and I believe that some day he and all his will be Christians.

I have not said anything yet about Siota. The work Comins and Welchman have done there is extraordinary. A large, fine board house raised on 99 piles, kitchen, workshops, store, lavatories, wells, gardens and fields have all sprung up, and there are 35 boys receiving their training in them, as happy as young princes. Excellent relations exist with the Gela people, who bring food almost daily for sale. Batches of men from different villages come every week and work at clearing and so on, receiving 6d. each for a day's work. While I was there I called together the Gela teachers for four quiet days in successive weeks, and Comins and Browning have since continued to get together every Friday a certain number of teachers for special teaching. This has brought us all together very much, and there is no doubt but that good has been done. The comfort of the European house at Siota is very great, and the difference between life in a native hut and life in a raised house with broad verandah and rooms full of doors and windows incalculable. An attack of fever in a draughty native hut is a different matter from the same in a good house which you can shut up and get warm in; there is a chance of shaking it off quickly in the latter. St. Luke's, Siota, is a hospital for all the white men in the Solomons. Browning and others can now stay in Gela as easily during the summer as the winter, and I believe a lady can live there as well as she can at Norfolk Island. There is always a breeze, always shade, and, so far as we white people who live there are concerned, we are always well. Browning does his rounds and comes back to Siota to recruit himself, and starts again with new strength and vigour. The fact of our living in native-built houses has not improved the natives' style of building, and as everything points to our white men staying longer and longer in the islands, they must improve their way of living if they are to do so and keep their health.

[6] Dear old Clement Marau is doing splendidly at Ulawa. He is now carving the interior wall of the chancel of the church he has built with blocks of sawn coral. Next he has to cut the timbers for the roof, and then he means to raise £40 to buy iron for the roof itself. He has set his heart upon an iron roof because the native roofing only lasts seven or eight years, and in rotting would spoil his walls. All this building is done in the hours when he should be in his garden. That work he pays men to do for him. At his school he has 80 people in regular attendance, so regularly that I found myself confronted with the difficulty of finding 80 prizes for them, for it was impossible to make any distinctions. They all attended daily. I had to examine them carefully and pick out the best, and so I reduced my prize list to about 40. All through Ulawa Clement's influence is making itself felt.

Santa Cruz has gone on well under Dr. J. W. Williams. We spent nearly nine days beating up to it. Having reached Te Motu at midnight, Williams came on board. His news was rather exciting. He said: "I'm awfully glad you've come; there's going to be a tremendous fight to-morrow at daybreak." We went ashore, and with very little difficulty assisted to put all straight, and next day the Cruzians traded freely with the ship, and I consecrated the new church and baptized some people. Williams had established his reputation as a medicine man, and the heathen availed themselves of his services constantly, paying fees of bananas voluntarily.

Robins has spent seven months in the Torres; all seems to be going smoothly there. In April I dedicated a church on Tegua, and found the people much in earnest. I have just visited Vureas, in the Banks, and dedicated a new church there. Crowds of people came together, and showed much enthusiasm. I baptized 60 people afterwards. At Motalava also a church was dedicated and a confirmation held. Altogether there are many bright spots in Melanesia, and much to be thankful for.

You know that Edgell has joined us. He is much wanted, and more men like him if we can only afford them. Expenses are frightfully heavy. I am weighed down by them.

Vila, September 7th, 1896.

We have put in here for coal, and I shall take the opportunity of posting this to you.

We are all well on board--Wilson, Dr. Williams, and about 30 boys and girls. The weather is cold, and we have put the youngsters into clothes to-day.

The big house scheme for the girls is by no means settled; in fact, some things which have happened lately at Norfolk Island make me inclined to view now the scheme with disfavour. However, we shall be guided to the right course, and shall then act.

Yours affectionately,

CECIL WILSON, Bp.

[7] EXTRACTS FROM THE "SOUTHERN CROSS" LOG. News from the Islands. The Southern Cross left Norfolk Island on July 7th, on her second voyage to the islands. She reached Florida on August 4th. The Bishop, Mr. Comins, and Mr. Browning were all well, and daily expecting the arrival of the ship. The first thing to be done was to go across to Guadalcanar to see how George Basile and Hugo fared, and also to put down Ellison Gura at a village, whose chief, he said, had sent for him. Ellison is in charge at Nago, in Florida, and much beloved by his people. It was a splendid piece of self-denial to leave his friends and home in obedience to the call that he had received from the heathen in distant Guadalcanar. His heart was set upon it, and he took the opportunity of the ship's visit to get a passage to the place that he might begin work at once. We soon reached Vaturanga, George Basile's district, and a native came off and told us that our "boys" had come down to the coast the day before and were waiting for us a mile or two up the coast. We were delighted to see them, and to see that God's blessing had been with them, and there was every prospect of a Christian settlement growing by the sea-shore. It must be remembered that there are no schools or churches in Guadalcanar. Two years ago Basile was sent to see if there was any opening at Savale. Alter suffering great hardships he decided that it was useless to try there any longer, and he struck into the bush to find some people who would receive him. He carried no books and no money. His plan was to make friends with those he fell in with, to stay with them and help them in their work, and let them find out by their own observation that his life was governed by rules different from theirs. He would live a Christian life amongst the heathen until the questions of the people gave him an opportunity to tell them of God, and of the Saviour of the world. The people were scattered, living not in villages, but in tiny settlements, and were constantly shifting their quarters. He followed them about, and he won their love. They felt he was better than they, and they asked him to teach them. He agreed to do so if they would settle round him, and he proposed that they should build a village on the seashore. The first house had just been finished when we arrived, and a large piece of land had been cleared to be used for gardens. With only two exceptions, all the people liked him, and would not hear of his leaving. Hugo Gorovaka, the deacon, and David are with George, and, like him, they are in much favour with the people.

It took us some time to reach Gavoga (or Tetere, for we are not sure that is really the name of the place) where Ellison was to be placed. The Austrian man-of-war "Albatros" was lying there. A German baron and a scientific party were cruising about in her, and at the time of our arrival were encamped a few miles inland. Saki, the chief, came alongside dressed as an Austrian bluejacket, having just received a present of a suit of clothes from our neighbours. His face fell when he heard that Ellison had come to give him a school. He had, it seemed, reconsidered the matter, and did not any longer wish for a teacher. His people also seemed rather disconcerted on hearing [7/8] the reason of our coming. They were all very glum at first, and looked twice at my presents before they received them. "Is a charm on it," said Saki, plaintively, when I offered a piece of trade tobacco. However, the little boys made friends with us, and then most of the men became more friendly. But they did not want a teacher, and when we had left them they told Ellison that he might stay if he pleased, but that if he did they would go away, for they were determined to have no school. After three days he saw it was useless staying there, and the Deputy Commissioner of the Solomon (Mr. Woodford), happening to arrive in a cutter, he went on board, and, by the courtesy of Mr. Woodford was returned to Florida. It was a disappointment, but the "boy's" effort was a grand one, and we get much comfort out of that.

We returned to Florida, and picked up boys for Norfolk Island. The Bishop and Messrs. Comins and Browning also attended the Vaukolu (native parliament), and spoke to the people on various local matters.

At Mala we found Mr. Ivens recently arrived from Norfolk Island. The Mala people have now their own Missionary, and they have received him with much enthusiasm. All was well there. At Ulawa there was much to encourage us. There were 80 people at Matoa in regular attendance at the school. The white stone church walls are finished. All that is wanted now is the roof. Mr. Wilson was at San Cristoval. Bo and his people at Heuru were flourishing under Gedi's care. They also are glad to have a Missionary, who will be able to give all his time to their one island. It must be understood that Mr. Comins' district has been an immense one. Mala, Ulawa, San Cristoval, and Ugi have all been ministered to by him.

It took us eight days and a half to beat our way to Santa Cruz in the teeth of half a gale. Late at night, on August 26th, we were off our first station--Te Motu. Dr. Williams came on board. He said there was to be a tremendous fight ashore in the morning, unless we could stop it. Without much effort on our part it was prevented, and by 3 a.m. we were able to lie down, feeling tolerably certain that there would be no trouble in the morning. It turned out as we hoped, and I was able to dedicate for the Christians their beautiful new Church, and to baptise eighteen persons.

At Vareas, in Vanualava, Mr. Cullwick had everything ready for the Bishop that he might consecrate the new stone Church, and baptise some sixty people. Both services were wonderfully hearty and inspiring, and the attendance of people at them extraordinary. Ben Virsal, and Marion (his wife), have done good work here, and God's blessing has evidently rested upon them and their people.

We reached Norfolk Island on September 14th. Thirty Melanesians had been picked up and were with us.

On this return journey of the ship the Torres Islands were passed without a visit, and the New Hebrides almost passed by, haste being necessary in order that the engine might be properly repaired in Auckland before the third and last voyage was begun.

[9] The Bishop in Florida. ________ FLORIDA, July 21st, 1896.

TO THE EDITOR,--

You will be glad to hear from me of what has been going on during the last three months. It is not often that one has an opportunity of sitting down and writing a long letter, but Captain Adams, of H.H.S. "Pylades," has kindly invited me to stay on board with him whilst waiting for the arrival of the s s "Titus," by which I am hoping to get a passage to Ulawa. She is now three days behind her time. Hence, my opportunity of writing you and the readers of

the LOG a letter.You know that most of us left Norfolk Island on April 9. Florida was sighted on May 6th. We put down the boys, dressed very neatly in new blue trousers, clean shirt and belt. I felt quite proud of them, and quite certain that they would make a great impression on their friends. I was proportionately angry when a grasping old grandfather came alongside in a canoe, and, seeing his grandson looking spick and span, demanded his clothes, and took them, the boy going ashore disconsolate and shabby. We sailed to Vatelau and Bugotu, then to Guadalcanar, to put down the Rev. Hugo Gorovaka, George Basile, and David, at Vaturanga, and then back to Siota, in Florida, where we said "good-bye" to the ship, and to those returning by her on May 16th. The captain said he would be back for us in eleven weeks. We had plenty to do before then.

I spent my first month at Siota, helping Mr. Comins to teach the thirty-five or forty boys he has living with him there. I need not tell you anything about Siota, because it has been already described in the LOG more than once. As it is to be Dr. and Mrs. Welchman's home, I will only say that, except for the banishment from one's friends, it is no hardship to live at Siota. The house is large and comfortable, well-built with Auckland timber, very airy, and beautifully placed on a hill overlooking Boli Harbour upon one side and the ocean on the other, with Mala in the distance.

As soon as I had settled at Siota, I sent a message to all the teachers in the island of Florida to say that I should like to meet them on four successive Fridays, that I might become better acquainted with them, and also that I might give them some teaching. These gatherings, week by week were very pleasant, and I believe they were good for us all. Mr. Comins, is continuing them himself every week, calling together the teachers from different districts, so that everyone comes at least once a month.

The last of my four gatherings was held on St. Barnabas day and eve. Sixty teachers came together and spent the two days with us. School was finished on the first day, on the second the Holy Communion was celebrated in the little Chapel, and sixty-three persons communicated. After breakfast the teacher's stores were distributed amongst them, and a cricket match was improvised. Most fortunately [9/10] in the middle of it a steam launch arrived bringing Captain H. F. Adams and some of the officers of H.M. "Pylades," with Mr. C. M. Woodford, the newly-appointed Deputy Governor of the Solomons. A match was at once arranged between the ship and shore, in which the shore gained an easy victory. We had a most enjoyable day. The St. Barnabas Association, and all friends of the Mission who are thinking of us much on St. Barnabas Day, were much in our thoughts.

There is not one amongst us--white or black--who does not heartily welcome the Deputy Governor. Everyone feels that we want a strong ruling hand to control these islands under British protection our teachers feel that it now too often falls upon them to see that wrong-doing is punished, and fines levied by the chief. This is work that they have no desire for, and would willingly see themselves relieved of. Where the natives are Christians there are not, I am thankful to say, many serious crimes permitted; yet two cases of murder have occurred during the last ten years, and the people have called upon us to settle the fate of the murderer. Only this year I advised a chief, who had awaited my arrival before punishing a man that had killed his wife, to banish the offender for five years, and to proclaim that the next murderer would be hanged. These are affairs that we dislike having anything to do with, and we are glad to have them taken out of our hands. Mr. Woodford knows many islands in the Solomons, having stayed for a considerable time at Aula, in Guadalcanar, and also in. Rubiana. He is a naturalist of no small repute, and has written a very interesting sketch of his life in Guadalcanar and the northern islands under the title--"A Naturalist amongst the Head-. hunters." Those who are anxious to know something of Guadalcanar, that great island which the Mission has made so many efforts to reach and win, should read this book of Mr. Woodford's.

Having spent a month at Siota, I commenced a cruise round Florida with Browning, which we had planned should take up the second month of my stay. I visited, during this time, all the thirty-two schools of Florida, except one. Of course, some were better than others. John Takesi at Gumalaghi has his school in splendid order. Frank Soro's scholars at Vura answer questions with great intelligence. And Berebere's people at Taouaiha, in the hills, quite surprise me by their forwardness. The smallest child in the school could read the Lord's Prayer in large letters. The teachers' registers had been very fairly kept, showing that the attendance had been good during the year. New schoolhouses were being built at Olevuga, Tanabono, Vurinimala, Halavo, Koilavala, and Longapolo. The building at Longapolo is a very fine specimen of Florida work. Five great poles, as straight and as smooth as masts, support the ridge of the roof. I lay on my back during a rainstorm and amused myself by making a study of the roof. The thatch is put on in pieces, each piece consisting of a reed seven feet long, over which are doubled and pinned some thirty pandanus leaves. The reeds are laid close together so that the leaves overlay one another on the outside, making a thick, but tight roof, which will turn the heaviest rainshower. In this roof at Longapolo, judging by the square patch over my head, which I made a study of, there were 6,400 pieces of thatch with 192,000 leaves folded and pinned over them. I [10/11] have seen men at Siota making this thatch, and twenty pieces made in a day seemed to be a fair day's work. The task of making 6,400 would need both perseverance and industry. But these are qualities which Melanesians have, I think, although they are never given credit for them. You will never find loafers and loungers in an island village. Arrive between nine and five o'clock and you will find any village deserted. Doors are closed, and except for some pigs, a few hens, two or three dogs and a cat you will see no sign of life. The villagers are all in their gardens three or, perhaps, more miles away, working at their little patches in the hills which have been chosen in preference to the land closer at hand, because of their greater fertility, and because of their distance from the village pigs. Every member of the family has his alloted work. The men clear the ground, dig, and do the harder work. The women and children plant, and weed, and at the end of the day bring home on their heads the yams or other food that has been gathered for the evening meal. There are times, of course, in the year when the people are not so busy, and the men can afford to spend a good deal of their time in fishing. Speaking generally, I should say that the Melanesian is not naturally lazy, and he is no lounger. He cannot do the day's work of a white man, and nature supplies his wants so easily that he need not do it. He does a sufficiently good day's work, and he does it on five days of the week. The Norfolk Island institution of giving Saturdays to the gentle art of fishing has found its way here and established itself, and there is little garden work done on that day. The seventh day of the week is scarcely known as Saturday. It is "Qon-rave iga" (fishing day).

This letter is a long one. I think I had better close it now, and write you another during the week I expect to have at Siota whilst waiting for the Southern Cross.

With every good wish for you, and the parish in Canon Calder's absence, and the little LOG under your editorship,

Believe me, very sincerely yours,

CECIL WILSON, Bishop.

_____________ PART II. St. Luke's, Siota, Florida,

August 2nd, 1896.To THE EDITOR,--

I wrote my last letter to you on H.M.S. "Pylades," whilst spending three or four days at Gavatu as the guest of Captain Adams, waiting for a steamer or other vessel to take me to Ulawa. The "Titus" was expected, but failed us. Another steamer carne in its place, bringing us the mails. It was bound for Rubiana, and all chance of reaching Ulawa disappeared with its departure. The cricket club of H.M.S. "Pylades" was anxious to play a match against Florida [11/12] before they sailed, so I got together an eleven hurriedly, mostly from the village of Belaga, and we had a real cricket match under the cocoanut trees at Mr. Nielson's station, Gavatu. The ship went in first, and scored 56 runs, the last man placing the ball securely up a tree, for which he was allowed six. Our men did very fairly well, and the match became exciting. At last we had made 51 runs, and all were out except two men. Luckily, then one of the batsmen did as our opponent had done and lodged the ball in a tree, giving us a sixer and winning the game. No more runs were scored, the wickets falling quickly, but we had made 57 and won the match.

I had a very interesting three days at Lango, Mr. Penny's old headquarters in Gaeta, a district of this island. It is one of the few remaining hill-villages. In these days of peace people do not care to live in the hills as they used to do in days of old. Then every hill was a stronghold. Gaeta was at war with Hongo across the bay, and every village in the country had its enemies. Men were only safe when they were well away from the sea-shore, and when a narrow and difficult path was the only means of access to them. Christianity has produced a great change in Florida. Mr. Nielson, a trader of thirty years' experience, says that twenty years ago Florida was worse than Rubiana, of head-hunting fame, is to-day. I have heard Bishop Selwyn say that it has the worst reputation in the Solomons. But that is all changed now. Search the whole world through and you could find no safer place to live in than this. Mr. Penny saw the beginning of the change, and had a good deal to do with bringing it about. Living at Lango, with Charles Sapibuana, he carried the church's crusade into district after district, and established schools in village after village, until he had the satisfaction, after ten years of work, of seeing most of the island Christian. Boli is the birthplace of Florida's Christianity, for it was there that Bishop Patteson made his first attack upon the island. But the chief of that place, after being the friend of the new teaching, afterwards turned against it, believing that it would overturn his influence, and Lango (in Gaeta), on the opposite side of the island, became the chief missionary centre in the island.

Kalikona was the chief of Gaeta in those days. He befriended the white man who settled amongst his people, but made no pretence to believe what he taught. Like other Florida chiefs he was glad to have a white man with him, particularly one whose presence brought visitors by a ship two or three times a year. It gave him and his people a chance of trading, and it also gave him importance, so he remained a fierce old heathen, whilst his people were accepting Christianity. In the end, before he died, he threw away his superstitions, attended school, and became a Christian. On the Sunday I spent at Lango I climbed the hill behind the village to the old stronghold and saw his grave, and heard his story. It may be true, or it may not be; at any rate it is the native version of the last chapter of his history. It was in 1880, Kalekona had lost some money, and for many days his face was clouded, and he would not be comforted. Then men began to say that only the head of a man taken, and brought to the chief, would end this trouble. It so happened that H.M.S. "Sandfly" was lying off the island at this time, and the Captain (Commander Bowes) [12/13] was seen to go ashore on an island called Mandoliana. All could be clearly seen from Kalikona's village. Then the women began to taunt the men, saying that they were afraid to take a white man's head, that if they were men they would go, and cut off the men who had gone to Mandoliana. The taunts were sufficient, and led by the chief's son, a party started for the back of the island. The bloody work was soon done, and the chief's anger passed away. But not so the white man's. The murder was speedily avenged, the murderers being caught and shot or hanged, and the village shelled. From this hill the trembling villagers saw the smoke of the guns at the ship's side, and the shells come flying over them with a fearful hum into the valley beyond the hill, into which they had sent their women. Three shells fell into the village. One passed through a house, one struck that tree, one burst overhead. My informant said that he and the other men sat and crouched as they saw them coming, adding slyly that Harry Korassi, one of my boat's crew on this journey of mine, "hid there in that hole." And all this happened only 16 years ago. It seems impossible to believe it.

Mr. Penny's house has fallen to pieces. Brave Sapibuana's is still standing, and his widow and children are living in it. Lango is a small place now-a-days, its people having migrated to the shore, but those who are left have not lost their first zeal. The school is well attended, and when Mr. Browning visits them, and celebrates the Holy Communion, there are many communicants. During Sunday afternoon a poor old widow brought us a bowl of most delicious food. "Tuti" they call it. It is yam mashed up with filbert nuts, and the pure white juice--not the milk--of the cocoanut. It is a most delicious mess, and the islanders' favourite Sunday dish. I was so much touched by my old friend's kindness that I straightway set off to pay her a call and thank her for her gift. I found that she was only one of three widows who kept house together for economy's sake, and very neatly and tidily they kept it. They were much pleased apparently at being visited, and, I daresay, talked about it. At any rate, all the village seemed to know that I had been to the house, and that I liked "Tuti," for on the next morning it rained "Tuti." From all sides streaming bowls of the blue creamy mixture came, until I wondered what we should do with it. The problem soon solved itself. I had a crew; and a boat's crew on a journey can eat as much or as little as you can put before them. They will go until evening without breaking their fast, or they will eat all day until there is no more to eat. During our immediately subsequent wanderings they followed the latter course, and the "Tuti" was disposed of.

Florida is more and more visited by men from Mala and Guadalcanar, the two great islands that lie on either side of it. Mala canoes are constantly coming from the little fortified islands, which dot the northern part of Nala, in search of food; and the Guadalcanar people are first cousins to the people of this island, and constantly sail across to see their relations, perhaps doing a little trading at the same time lest it should look too much like a mere holiday. More and more is the peaceful condition of Florida making it a meeting place for the [13/14] Solomon Islands. It is from here, I should think, large tracts of country in the other islands will be evangelised. There are now staying in this island some sixty or more Guadalcanar people, whom two years ago a fierce tribe overcame. Their friends on this side heard of their danger, and fitted out an expedition of many canoes and fetched them to a place of safety. As yet they follow their old customs and decline to go to the schools, but it is probably only a matter of time, and they will accept the faith, to return with it some day to their own country. A more determined effort to reach Guadalcanar was made by Ellison Gura, one of our teachers. He had received an invitation, he said, from Saki, chief of Tetere, to begin a school among his people. He never hesitated a moment as to going or not, and in the Southern Cross we carried him and his box across the sea to his destination. The chief was startled to see him, and said he was troubled because now he would have to give up doing what he liked. I tried to comfort him, offering him a small present. He held back his hand and looked piteously at me, and said "Is it tabu?" The people were less friendly than he was, and did not seem at all to like the notion of a school. In the end they were too much for poor old Saki, and Ellison was sent back to his own country with the notion in his head that it is one thing to visit your cousins for pleasure, and another to visit them on such a business as he had come on. I must close now.

Yours most sincerely,

CECIL WILSON, Bishop.

___________ ISLAND VOYAGE 1895.

________BANKS' ISLANDS. The Rev. T. C. Cullwick reports:--

The ship having to put back to Auckland for repairs, made us very late in getting to our work in the Islands. The people who had been keeping such a continuous look-out for so long a time had grown weary of waiting, and had quite made up their minds that the vessel had 'sat' upon a rock.

I found Mota in a very unsettled state. Feeling ran very high against a man who at one time was considered one of our greatest helpers, for making overtures for marriage to the fiancé of another. On inquiring into the matter with the head men and others, a very unhappy state of things was found to exist, which led us to a spirited demonstration against the wrong-doers, and when this was done the unsettled state of things began to subside.

On leaving the District last year the people round Mota took up very warmly the proposal to build a new church worthy of the old associations of their past history. They undertook to raise so much [14/15] copra (dried cocoanut) sufficient to buy an iron roof. It was very disappointing, therefore, to find that so little had been done. From what they had to say, it appeared that their confidence in the trader had begun to subside, and they were very anxious for this to be accepted us an excuse for their apparent indifference, and it was not without some show of reasonableness. Later on they began to stir themselves up, but a very severe epidemic passing through the group laid them all low for a very long time, and completely paralysed all work.

On the first evening of my arrival there were many inquirers after small hooks, which the trader of the district fails to supply. The following day a great crowd of people came together with heaps of yams as soon as prayers was over, and kept themselves in a very good humour until school was finished and breakfast over. We then adjourned to the landing-place to commence the market. This move was the fruit of experience gained as a freshman, when I found myself with a great pile of yams on my verandah and no one to carry them down to the boat when wanted.

At one time the Banks' was looked upon as the chief place to get food, and many boat-loads were frequently bought and were always welcomed at Norfolk Island; but since the advent of a trader it is a matter of congratulation if enough can be got for the use of the ship. The trader's station is only across the passage, and as there is a continual round of 'famine' in tobacco most of the yams find their way across. There are several kinds of trade which can only be got from us, and there are always a quantity of yams kept in store for these. The trader's tobacco is the 'string' tobacco, or twist; our tobacco is the 'pudding' tobacco, or flat pieces, and this latter is held in high esteem. Then the trader's hooks have no eyes to take the line, and are called needle points, and the many disappointments at losing perhaps a big fish after a long days work have created a prejudice against them. The big pile of yams, the result of our morning's barter, was a most gratifying sight, and was still more so when the ship returned from the North on rather short commons.

After giving a day to general matters at head-quarters, I commenced my round of the Island, taking the different schools in turn. The attendance generally was very disappointing, and this necessitates a great amount of energy being spent in endeavours to bring it to a more satisfactory state. When one pays the usual visit the whole crowd invariably turns up. This is something to be grateful for, as it gives one the opportunity of having a say and giving them a flesh start. There very frequently arises some petty squabble or other, nothing at all perhaps to do with their attendance at prayers and school, but which is often made as an excuse for their non-attendance, and this has to be cleared up by the missionary. The latter, unfortunately, is almost always constituted the court of appeal, and so things very often drag on for a long time, instead of being settled on the spot by the powers that be. The people generally have a strong belief that it is the prerogative of the white man alone to rule and reprove. It is a very common reply to many teachers when [15/16] attempting to exercise their authority, 'Are you a white man?' which frequently has the desired effect.

At one school a regular scold of a woman had kept the school practically closed, and on remonstrating with some of the older ones, they said: 'Oh, she won't listen to us. We were waiting for you.' She had insulted their dead relations, and so she was past all hope, and because she happened to live at that particular school village the people gave her a wide berth and didn't attend school.

The school at Navgoe is in a great tangle, and has been so for a long time, notwithstanding the repeated efforts to put things in order. The head teacher is a good natured sort of fellow, but utterly incapable of filling such an important position. A good building has been erected, which they are very desirous of having consecrated as a church, but they will not build a decent school-house, and as the use of the church building for school purposes is most undesirable the present building is at present only used as a general school-house.

One of the other teachers is also an old identity, and is called 'the poet.' He is a great invalid, and only just able to drag himself about. He still invokes the Muse, and entertained the Bishop during his visit with several songs old and new. He is no longer, however, the popular poet, another of the present generation having arisen, who has caught on with which might be entitled 'The Copra Ship,' written in the poetical dialect of Vanua Lava. The two senior teachers being to a great extent incapable, it has been a difficult matter to find some one to take the practical control without hurting their feelings. The mission has, however, been undertaken by a young fellow just back from Norfolk Island, who will, it is hoped, be able to cope with the unsystematic state of things.

From Mota we sailed to Motalava, and found that the people at Ra had made laudable progress with their new church. Most of the large timber have been cut, and were already in their places, and it fell to my lot to sketch a plan of the interior, as that is quite beyond the native talent On a second visit we laid down the floor of the sacrarium in concrete, and left the rest to be done by themselves. It turned out a great success; the lime made of the coral was excellent the stone walls and concrete floor giving a very substantial appearance to the building.

The font is a large clamshell brought from the Solomons, and is mounted on a pedestal of concrete, with a base of the same material. During the bishop's visit the church was consecrated amid much rejoicing and thanksgiving. The collections were made in three different kinds. The cocoanuts made into copra amounted to 1,351; The English money to £3 5s. 9d.; the native money to nine fathoms and a-half. The village of Ra will soon be a model village, having already a well-taught school, a very devotional congregation, and a well-built church. The next thing being to do is to turn our attention on the school building and the vicarage; the only redeeming feature of the latter is its boarded floor. With all this to be so thankful for, there is an element of sadness to temper our joy. From [16/17] time immemorial there appears to have been instances of leprosy. The 'people' here have got a name for it, and there are medicine men who profess to know its cure. It is now very much in evidence, and is confined to children. Last year we were enabled to start a leper colony, isolated from the other villages, and many were the devices of diplomacy to which we had to resort. The idea was so very foreign to the people that it appeared to amount to direct cruelty, and they could not reconcile it with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. We got their houses built, and started them with a stock of poultry and other things, but with all this a great amount of pressure had to be made, and many threats given, before they conformed to the rules laid down; in fact, a demonstration had to be made with bows and arrows before they became reconciled to their fate. This year we found that they had taken very happily to their isolated life, and said that they had no desire to leave their little settlement. They now number nine, between the ages of five and seventeen, two fresh cases having broken out this year. Such a large proportion fills us with forebodings for the future, and casts a gloom over a work which has prospered so

greatly.The Totoglag school was found to have progressed splendidly, but they were lamenting the death of a teacher named Simon Qon, who had done his work conscientiously and faithfully, and had helped greatly towards the present progress.

On the other side of Motalava there were many things to be found which caused regret. The 'suqe' had again established its supremacy, and the teacher had returned to his native place at Ra to await my return.

Some years ago they all came together at a great meeting, and promised not to do anything connected with that particular custom which would interfere with their religious duties. The 'suqe' is an institution connected with the club-house, and is the means of obtaining rank. It entails a very long residence in the club-house, from which the one being initiated is not allowed to stir out, and so here it comes in conflict with their duties as Christians. In the old times the number of days required to be kept was a hundred, but lately, as a result of our attacks upon it, the days have been considerably shortened. In the present instance, the man in question had only kept commons in the club-house for forty days, and the old headman of the place thought he had made a great concession, and was quite surprised to find himself under a storm of abuse.

Another trouble had also arisen which had unsettled the district. A man had absconded with the wife of another, and had wounded her husband in the struggle which ensued. He appears to be thought somewhat of a warrior, and the people were afraid to take the matter up. There are headmen chosen by the people to deal with questions affecting the public peace, but they are so slow at taking the initiative. Of course it must very often involve a fight, as the wrong-doer has very often some one to back him up with his bow and arrow. At one time all the places were simply bristling with bows and arrows, and the people had to be taught very forcibly that there was [17/18] a great sin inherent in fighting. In the more advanced places it has taken deep root, and now, when called upon in the interests of public order to tackle an offender, they very often give him best.

We had a very large .meeting in the school-house to talk matters over. They all agreed that it lay with themselves to make or rather renew the promises for the reform of the 'suqe,' and that they had no longer to fear a crotchety old chief called 'Six-fingers,' lately deceased. From what happened afterwards, when several became initiated into the order, we found that they had stuck to their promises.

The man who was the cause of the other trouble was then discussed, but they seemed to have softened towards him in their feelings. They said that at first they were very angry, and wanted to judge him, but that now, a long period having intervened, their hearts were soft again, so there was nothing to do but to try and get the better of him by moral force. This, however, was spent in vain, for he was still in his sins on our last visit, and seemed impervious to all effort to reclaim him.

At Vureas, VANUA LAVA, were spent a very happy time working at the new church. The people responded splendidly, and we commenced to build the walls. The stones near at hand were considered unsuitable, and everybody said what good stones were to be had on the other side of the bay. This seemed to be an endless task, but the party of youths, with two Norfolk Island boys at their head, would have no denial, so they pressed my boat and another into their service, and spent several days as a preliminary. On our last visit we found that the work had received a very serious check--the then prevailing epidemic had attacked them severely, but it had just then left them, and we found some of the more earnest ones hard at work.

There appeared to be a great wave of earnestness passing over the whole place, and on my second visit I was very much astonished to be told that seventy-two people were preparing for baptism, and had proved themselves greatly in earnest by their regular attendance. They were mostly from a place a short distance away from the school, and although they were considered as belonging to the school, they had jealously kept themselves away from the school people proper, and any little squabble served to widen the breach. One day they came in a body to Benjamin Virsal, and said what their convictions and wishes were, and asked him to prepare them and their families for baptism. Some years ago they suffered a great deal of damage from an inundation and a land-slip, and many were taken in and cared for by the school people. This Christian service opened their hearts to desire Christian teaching, and the grand ingathering which took place during the Bishop's visit had its beginning in that little act of kindness.

At first it seemed to me that a temporary school should be given then, and thus ensure a more thorough teaching, as they hadn't the advantage of being able to read; and as something to console them for such delay, I said how peculiarly fitting it would be for their baptism to take place at the consecration of the new church next year.

[19] On our next visit with the Bishop, they were still found to be very regular in their attendance, and very desirous for baptism, and I was asked to hear them their catechism. In this large class there were several old men and women, and most of them were middle-aged, and this very much increased my astonishment when they said their catechism off by heart from beginning to end. This was so very conclusive of their earnestness and fitness for the grace of God that we felt they had a right to ask for baptism. The Bishop baptised them on the last Sunday of our stay, under the large dela-nut tree on the beach, and as they were presented in families to receive the rite, our hearts felt very fell of consolation and thankfulness to God for giving us such a manifestation of His power, and such a proof of His abiding presence, to crown the past year's work.

In Easter week we had a succession of celebrations. I called the Deacons together and we made a scheme. We divided the whole place into districts and allotted a day for each giving them particular directions as to which day they were to come and when to go. It worked very well, and nearly all the Florida communicants came; only those who were unavoidably detained stayed away, and most of those came on Low Sunday. It saved me the going from place to place and the people enjoyed their outing.

Our boys enjoy going to chapel and very rarely miss, in fact I don't think they ever did unless they were really ill. Before prayers I always gave out the hymn and psalm for the day and left them to find their places, and they soon got in the way of it and brought their books for me to see whether they were right or not or to help them if they were wrong. The hundreds always puzzled them and a good many stumbled over the tens, but they were getting pretty well used to the books by the time I left.

The boys have calico served out to them at intervals, a dark stuff for working in and a white one for meals, school and prayers. I should have preferred having some other colour than white, it gets dirty so soon, but there was nothing else to give them. Our land is very red and marks everything very quickly, but the boys take rather a pride in keeping their clothes nice and take them off as soon as the proprieties are served, except some of the harem scarum little rascals who never can be clean for half-an-hour together. Some of them sport shirts for Sunday but not all, for I forbade all dirty and torn articles and some of them were very disreputable. Anything that can by any means be called a shirt is a lovely thing to them, even though the sleeves are gone, and the tails and perhaps one button hanging by a single thread is all that remains to fasten it by.

You may remember my telling you that I had brought away some women and children from Rubeana (New Georgia) when I went down there about the murder of that trader. I brought them to Siota and they remained under the care of Louisa. The elder woman was a rank heathen and did not care to learn any Christianity, but the younger, a girl about twelve, came to school regularly. I noticed her garments were getting rather the worse for wear and not always particularly clean and made enquiries. Poor thing, she had no others, [19/20] so I had to furnish her with the material and Louisa helped her and shewed her how to make her clothes, of course of a very simple description. She looked quite shyly proud of herself when she appeared in a neat skirt and bodice. There were three small children at first, but the youngest, a handsome boy about 6 months old had whooping cough and died soon after the Southern Cross left us. The two little girls, about five and three were great pals of mine, and were always hanging about the house. Nelly, the elder, came to school and it was wonderful how she got on with her letters. When I left I had to take them all to Bugotu but I hope to get the children again some day. They are now staying in a village where there is a school, with a good fellow for a teacher and a steady girl for his wife. He may be able to do something for the mother. Toward the end of my stay we allowed Nelly to come to prayers with Louisa and very proud she was of the privilege, sometimes getting to the chapel door before Louisa, and patiently waiting outside till her chaperon appeared, and she always behaved beautifully.

_______ The following extract from Rev. H. Welchman's letter, written on board the "Southern Cross," after leaving Siota, will show the sort of work that had to be done to render the place habitable and efficient:--(See Bishop's Letter above).

"The greater part of our work consisted in building houses for all sorts of purposes, all of native manufacture--that is to say, after the usual native fashion. They rejoiced in it, for they did not at all care about the alternative work, which was clearing, unless indeed it involved chopping with axes; then they were quite to the fore, and, little fellows would chop away with axes nearly as long as themselves. The first thing we wanted was a lock-up storehouse, for all our things lay in an open boathouse, and it was a great temptation to any one to steal. Of course, while we were living there, there was always somebody about; but when we moved up to the house, which we did the day after the ship sailed, the place was often left for hours unwatched, and exactly opposite the place where everybody landed when they wanted to go to Belaga. We had a sort of framework ready to hand in the timber shed, now quite empty, so I decided to utilize that. We had all the posts ready fixed, and it only remained to fill up the walls. This we did by cutting down trees, and laying the trunks on the ground and tying them to the posts. It was a good-sized building, and it took us a long time to raise the walls six feet. Some of the logs were heavy, and took four or five of the boys to carry one of them, but as we got higher we used lighter ones. Then we had the roof to do, and this bothered me a good deal, for we could not fix the corrugated iron without nailing it, and I was unwilling to spot the plates for future use, as this we were working on was only meant for a temporary building. After several abortive attempts to succeed, we took down all the iron and resorted to the usual thatch. Then we made a broad platform on each side; I hung the door and [20/21] we were ready. It took us about two days to get all the things carried from the boathouse, but we got everything safely housed. I turned the key upon them, and felt that one important point was settled.

"Another job we had was beyond our powers, so I went across to Boromoli and engaged some men to come and help. There was a native house near the landing place, in which George Basile and the women and children lived. I wanted to have them nearer to me, as the Rubiana party were afraid of living at a distance, and I, too, did not care to have part of my charge so far away. The material of the house was good still; it would take many days to build a new one, so I made up my mind to convey the house to the hill. About 30 men came and undertook the whole job. I had all the moveables carried up to the new house, and then they began to take the house to pieces. Cutting the ties, they separated the walls, took down the roof in two parts, and then dug out the posts. Then they carried up everything: first the posts, which they set in their places, and then took the walls and roof and set them against the posts and tied them on. Before night all the furniture was back in its place and the occupants settled in the house, having never slept a night out of it. We were rather proud of it, although it is not a handsome house, and the floor got somewhat damaged in transport, so that we had to almost make a new one.

"After that we set to work on a composite house, which was to serve for dispensary, butler's pantry, and stores for immediate use. Hitherto our butler's pantry had been on the verandah, and consisted of a big box supporting a smaller one with shelves. This house was to be nearer the boys' kitchen for convenience sake, and so could not be made of leaves; but we set up posts as usual, made the walls of palings, and covered it in with iron sheeting. The middle of the house was for stores, and held biscuits, meat, etc., to last a week or two, and was under lock and key; nearest the kitchen was the butler's pantry, and at the other end my little dispensary, which I honoured with a floor of palings: not a very huge place--10 feet by 4 feet 6 inches--but it held my bottles, and that was all I wanted.

"Then we had to build a house in which to store our yams, washhouses for the boys and the women, two boathouses at the beach, and other small buildings; next we put a house over the tripod which carried our bell, and, urged by ambition, I added a steeple of thatch about 6 feet high. It looked quite imposing with a small cross on the top of it. Our last work which we finished before the ship came was the erection of a carpenter's shop and the paving of the road from the house to the kitchen, so as to avoid carrying dirt into the house. While all these were going on there were short intervals which we employed in beautifying the ground round the house, laying out paths, and planting and clearing away stumps. Altogether I was very well satisfied with the way in which the boys worked, and the Bishop seemed to be satisfied with what had been done."

[22] Diary Letter from the Rev. L. P. Robin, Torres Islands, during the summer months of 1895-96:--November 6th, 1895.--Arrived off Vipaka, at Lo, about 11 a.m.--tenth day out from Norfolk Island. Got all landed by about 2, and Southern Cross went on to the North. Spent afternoon in unpacking stores, etc., for seven months at least. All going on well here, but William and Nesta are very poorly.

November 7th.--Finished unpacking in morning. In afternoon went up the mountain to see the Taratawe new Church and School, and paid Ernest a visit in his garden. There has been hardly any rain for three months; the planting is consequently thrown late. I decided to run over to Tegua that evening, and hear the news there. Accordingly after Evensong I set off with my boat and crew. We had a slight breeze, but it did not help us much. In spite of my lantern, which we kept burning all the way, we were not seen at the school village. But luckily I had brought my conch shell, and a few blasts presently produced an answer. Before long there were enough natives down at the rocks to help us to land. We hauled up the boat, and went up to the village at once. My eyes were delighted on arrival by the sight of a splendid building--the new church. I will give a description of this when I tell of the opening. Meanwhile services are still held in the old school. The report was not good. In the first place, soon after I had left them last year, the boys had quarrelled while playing. They proceeded to have it out with fists, and presently the rest joined in, and there was a regular melée. The split continued with desultory engagements for some days. It was at length decided to make peace; here the Elders, who should have stopped the thing at the outset, stepped in. They now decided that the usual interchange of pigs, etc, must take place as if after a regular grown-up affair. But the children had nothing to give; but the elders demanded that they must "pay" them. (This, of course, sounds unintelligible to us, but it is founded on the native way of making peace; though even so, there was absolutely no excuse for their conduct, which was simply due to gross covetousness.) The children were ashamed before the Elders, and a labour vessel arriving, as they thought very opportunely, some 10 or 15 of them went off and recruited, previously leaving word for me, when I should come back and find them gone, that they had not wished to go, but the Elders had made them ashamed, and they were unhappy. Thus nearly half the school was lost. The second affair was more recent; in fact, had only just occurred. Luke, the teacher, was accused falsely, and strict enquiry failed to establish anything wrong at all. The result, however, was that on Tuesday (this was Thursday) Luke had gone off to a labour vessel then lying in Hayter Bay and recruited. He was followed the same evening by a party of women. This caused consternation, and on Wednesday morning several of the head men went to the labour vessel and succeeded in getting all the deserters returned--the women as not given permission to go and Luke as a teacher. The vessel left that afternoon. I arrived the following day and received the news. Luke returned next morning.

[23] November 8th.--I had a talk with Luke. Afterwards I spoke to the people about it and about the other matter. I left again about 10 a.m., and got back to Vipako about 1. My visit convinced me of one thing--viz., the necessity of placing Ernest here, at all events for a time, to get things into proper order and to strengthen Luke's hands. As soon as we can get the school carried on with regularity, and establish rules for behaviour in the school village itself, we shall get on better. James, the other teacher, having been a Norfolk Island boy, has more authority with the people than Luke, who, however, is worth six of him in appreciation of what is right and in accordance with Christianity. But, considering the recent affair, I thought it best to bring Luke back with me to stay for a time with Ernest and Emily (his sister) at Taratawe till the unpleasantness has blown over.

November 17th.--Twenty-third Sunday after Trinity. Early celebration of Holy Communion. Service took two hours. About 40 communicants. The offertory, in kind, consisted of yams, which I buy afterwards, and put the money to our offertory account. Preached in evening. We had only one sermon as a rule on Sundays, the Sunday School in the morning, together with Matins, forming quite as much as any one can receive with advantage in this hot climate.

November 23rd.--Erected a boat shelter, and hewed and burnt a short slip through the coral to facilitate launching and drawing up the boat. "Burnt"--a fire is lighted on some huge lump, and kept going for two or three hours: then the fire is cleared away and water poured on, which causes the coral to split and become soft and easier to clear away. Of course, this can only be done here and there, where one has a specially big lump to deal with, or a cropping up of the more solid and hard sort on which the pick makes little or no impression.

November 24th.--Browning came off with me to Matins, and kindly preached. After this the boys for Norfolk Island went for their belongings, and Browning and I had a good talk, which I felt I wanted to make as much of as I could, in the expectation of the unlikelihood of enjoying such a luxury for another five months or so.

November 30th.--St. Andrew's Day. Full congregation came for Evensong, being a Saints' Day. I preached, and had preparation for Holy Communion afterwards. After that I went to see Nesta again, who seemed stronger. Her husband thought her out of danger, but later in the day there was a sudden failure of the action of the heart, and she died at once. I hushed the people to say the Prayer of Commendation. Throughout the whole night the wailing went on, mournful beyond description.

December 1st.--Celebration of Holy Communion early. The funeral took place instead of Sunday School. I ordered three weeks' mourning in the two school villages. She was the only woman teacher we had, and did her best; was always gentle, and willing to do anything she could for any of us. She is a great loss. This week I began my baptismal classes. The candidates had already been attending instruction by William for three months; it only remained for me to tighten the cords, as it were--going through the service in detail.

[24] December 10th.--A party from Toga came over as usual in one of their absurd bamboo rafts. They came to see me, and we had a long talk. They told me there were many of them willing and anxious to do as the Lo people have done and receive our teaching, but their Elders threaten all sorts of evil to them, by charms and otherwise, if they consent to it. I suggested that scattered they could do nothing, united they were strong. Let those who were willing to do so leave their village and build a village for themselves near the place set apart for the school settlement, where, as they would be together in considerably larger numbers than their opponents, they might be safe and happy. They would also be near to the school as soon as I could find some one to teach them. They thought it would be a good idea, and said they would speak to others about it and see. I promised to go and see them, weather permitting, on the 12th. They gave a very discouraging account of the Tugjä people (the southern part of the Island). These appear to be very strongly opposed to us, and have vowed and decided that no missionary shall come near them. One can not wonder at it. Nearly all have been away to the plantations, and are irritated and debased in consequence.

December 11th.--I had the final baptismal classes from this time till Christmas. Nearly all the remaining heathen adults will be baptized, but some are put back for a time. I hope to baptize them, if satisfactory, at Easter.

December 14th.--Over to Togä for one night. A good passage, and plenty to receive us. After Evensong with my boat's crew, we had a talk altogether about my plan. They profess to call it a good one, and seem inclined to carry it out. At all events, all opposition worth mentioning is now over in this part of Togä, and the people are only anxious to have a teacher. Where one is to come from I know not; but in due time "God will provide."

December 13th.--More people came together this morning, and 30 or 40 gave in their names as willing to begin by throwing up the suqé. Also another boy was brought to me and handed over for Norfolk Island, and an older one offered to go, but I fear he is too old. However, I decided to take him to Lo, and see how he does in the school there; if satisfactory, I may take him on to Norfolk Island, specially as we have only two besides him from Togä. However, I anticipate no difficulty in future about getting lads from here. Back to Lo in the afternoon.

December 19th.--A sharp attack of ague, and, I think, influenza quite incapacitating me for anything.

December 22nd.--Able to take my Baptismal class and help at Matins, but rather weak.

December 23rd.--Holidays began, but I had my class for Baptism morning and evening, and kept as quiet as I could. In afternoon I gave my Christmas presents, every Christian and candidate for Holy Baptism getting something. I had thought of having a "Tree," but gave it up, as I was unequal to the bother, so we merely had a [24/25] gathering in the school village, and I gave away the things much as we do generally at a school feast; but the prizes were somewhat different--a pig, a big axe, mattock, pieces of print, knives, belts, etc., pocket knives, long bush-clearing knives, fishing lines, hooks, needles, cotton, tobacco, towels and soap; all useful articles, and I think the recipients were pleased.

December 24th--Short final school with candidates in morning, after Matins. After that, pretty hard work all day decorating the church. All was ready for Evensong, which was festal, and during which the baptisms were held. Hymns, translations of following A. & M. Processional, 215; after Lesson, to font, 263; after "Reception into the Church," 540; Recessonal from Font, Nunc Dimittis, after 3rd Collect, 220; Recessional, 62. Nineteen men and 19 women were baptized. I had some difficulty in getting through it, as I was very tired and still very feeble after my sick bout. I have the Processional Cross taken to the Font during Baptisms; it seems very appropriate, and impresses the idea of "fighting under Christ's banner." I had decided to have the Service of Holy Baptism on Christmas Eve, in order that we might rejoice together as Christians on the Great Feast itself. The Font looked beautiful as usual, the great white shell nestling in the midst of ferns and small palm fronds, which covered the wooden pedestal from bottom to top. I used the beautiful Baptismal shell for the first time............

The rest of the letter describing Christmas Day has not been sent to me._________ He gives a further account of Lent and Easter at Lo.--ED.

I spent the first 4 1/2 weeks of Lent at Tegua, returning to Lo on the Monday after the 5th Sunday. On Palm Sunday we had a Celebration. The Evening Service I made preparatory for Holy Week. I was doubtful how far the people would attend the extra services, and you may imagine how thankful I was to see the church full for every service throughout the week. On Good Friday we had the Ante-Communion at 6 a.m.; Matins and address on events up to the Crucifixion at 10; Litany, hymns, and address on the Crucifixion at 2, closing with five minutes' silent prayer at 3; Evensong and short address on Burial at 6-30. We had had very wet weather all through Lent, but fortunately it cleared up on Good Friday, and lasted so through Easter. On Saturday Evensong was really grand, fully choral, with the baptism of 19 adults. On Easter Day we had, of course, the Early Celebration at 7, and choral Matins and Evensong, with sermon. On the Tuesday afternoon I went over to Tegua, where on Low Sunday we had a grand Baptismal Service in the evening--no less than 41 Catechumens.

[26] A MISSION WEDDING. The following account of the wedding of Rev. H. Welchman and Miss Helen Rossiter gives a graphic description of the simple but joyous festivities which attend such an event at Norfolk Island. And they will awaken deeper thoughts in our readers than those which a wedding usually suggests. For Mrs. Welchman will be the first lady of the Mission staff who has gone to reside in the Islands. Her training in Norfolk Island will fit her in every way for the life at Siota, and if her health is spared she cannot fail to be of the utmost help to the women at Florida. Our readers will notice the description which the Bishop gives of the change which has come over Florida; and it is no little proof of the reality of the change that it should be selected as the site of the new central schools, and as the residence of the first white lady who goes to live in the Islands.--ED.

"'The Day' turned out lovely. After a spell of squally, dirty weather, the wind went round, and brought with it a few pleasant days, which dried the roads, but left them without dust, and the 30th July was a 'perfect' Norfolk Island day. Decorations had been going on all Wednesday, and were carried out to the last minute almost. The signal flags did duty as usual across the roads. There was a high arch over the 'Vanua' * [* The gate leading to Mission enclosure where the hall and chapel stand.] gate, and a double motto above it--outside, 'The Lord be with you;' inside, 'I Lord ni vawia kamurua' ('The Lord bless you two'). The paths were carpeted! the porch pillars covered with evergreens and roses, and the chapel was decorated with young palms from the bush, set in pots, and arum lilies and roses, etc. Several of the young Norfolk Islanders were galloping about in the early morning, so as to bring in the arums quite fresh. The chapel was filled to overflowing, as besides the Mission party a great many of the Islanders came. The boys wore their red shirts for the first time, and looked very spruce, and the girls were not behindhand in adornment.

"The wedding was performed by Archdeacon Palmer, who gave a most helpful address at the end, and finally commended the bride and bridegroom and their work to the prayers of the congregation. After this the hymn 'Perfect Love' was sung in two languages, so that all could join. As the happy pair left the chapel they passed under arches of palm branches, held by rows of boys, and then stood on the grass to receive cheers from the boys and congratulations ad lib. from the rest of the party.

"The wedding breakfast was held at the house of the bride's mother, in a verandah which had been enlarged for the occasion by walls of Mikan palms, which extended it at each end and enabled the 130 guests to find room. It was a proper Norfolk Island feast, at which turkeys and sucking pigs always play a conspicuous part, and the cake, made on the Island, was a work of art.

[27] Dr. CODRINGTON sends the defence of a translation used in the old Florida prayer book:--

Every friend of the Mission is grateful to the Bishop of Tasmania for the "Light of Melanesia," but I regret that he has inserted a story which holds someone of the former Clergy up to ridicule, and I think I may be allowed to shew how entirely that ridicule is undeserved.

In the first place, Ps. civ. (a verse of which in a Florida translation is the subject of the story) was translated into Mota from Hebrew by Bishop Patteson, and from Mota into Florida by Alfred Popohe a Florida man.

Next--Bishop Patteson's Mota translation of the verse, still in unquestioned use, is literally in English "devouring pigs drink to stop their thirst." Where the Bishop used the Mota qoe Popohe used the Florida equivalent bolo. It is enough to say that qoe and bolo stand for "beast" in general, as Kuri, dog, does in Maori, and manu, bird, in Fiji. The Bishop wrote qoe Kurkur, devouring beast, that being the accepted Mota for a beast of prey. Why he should have been content to call a wild ass by that name is another question. Popohe added tinoni, man, and made it "man eating beasts." This was because the Florida gani, Mota gan, is not so strong a word as Kur, which is always used in Mota of canibal eating. To Popohe the wild beasts, of which he had often heard as qoe Kurkur, were such as eat men. He did not know that these were asses, he followed the Bishop.

In the third place the joke depends on the translation of the Mota marou by the Florida marohu, and the translation of that by "hiccups." Now Popohe was talking Mota every day and could not have failed to know the very common word marou, thirst. He knew Mota from inside, as a Melanesian, not from outside as an Englishman; very likely he knew what marou meant better than any Englishman. He translated it by marolau; I believe marolau and marou to be the same word. But what is marolau? An excellent authority says it means "hiccups," but an old vocabulary puts it down for a choking in the throat. It is inconceivable that Popohe could have taken Mota marou for hiccups. Translate marohu "hiccups" and the effect is ridiculous; but translate it dryness, irritation, choking in the throat and the sense is good; and the meaning of marou is most likely the same. But why did Popohe not use the common word in Florida for thirst? Because that is "want to drink;" and he thought "drink to stop their drowth" better than "drink to stop their want-to-drink;" in which I agree with him myself. R.H.C.

Mrs. Robinson of Mackay, who for seventeen years has worked almost single handed among the Melanesian labourers in that district, with the utmost devotion, sends me the following pitiful letter. She has won the love of the boys all round her in a very marvellous way, and through years of depression has managed to keep up the School. The Bishop has helped her, but as her letter shows has now been [27/28] obliged to reduce his grant. Can the readers of the Occasional paper help to tide over the difficulty. It must be extra help, as the mission is, as the Bishop's letter shows, in such low water that he is in the greatest anxiety about the funds. But still we ought to be able to raise £75 for this year, and then see what can be done. I will start the subscription with £10--will others send what they can to me that I may cheer Mrs Robinson's heart. It must be done soon.

(J. R. SELWYN, Bp., Ed.)

Selwyn Mission,

Mackay,

Queensland,

Oct. 26, 1896.Dear Bishop Selwyn,

You will regret I know to hear that there is great likelihood of my being obliged to close the Mission School. To say that I regret it deeply, cannot express the half even, that I feel about it. Bishop Wilson writes "I am anxious to incur the responsibility no longer." He is speaking of the £150 a year promised me before, on which it was agreed I should live and undertake also all expenses connected with the Mission. Bishop Wilson adds--"we shall go on paying £70 a year towards your work so long as we have funds to do it." I am afraid I cannot possibly keep myself and my daughter on this and pay all expenses.

Last year we got through a Sale of work, got up by a Mackay lady--£49/15/0, but this year there will be nothing, I am sure, from Mackay, because it has been and is the worst season ever experienced here in the remembrance of the oldest inhabitant, and they have great difficulty in raising enough for the stipend of the Clergyman and the expenses of the Church. Fancy after 17 years, to have to stop! It will be the greatest blow to me. We have scraped on as little as possible so as to aid the real work the more.

My hours are from 9-30 to 11-30 a.m. for South Sea Children. Then I arrange School for evening, set copies, &c., then visit the sick. Evening School for adults is from 6-30 p.m. to 9-30 or 10, and then doctoring the "Boys" as I am well acquainted with medicines having learnt for some years from a good doctor. The very sick boys, who come and ask sometimes, I take in and nurse till they are well again.

On Saturdays and Sundays the place is a sight worth seeing, with all the men, women and children from all parts, some coming 6, 8, 10, 16 and even 20 miles!

On Sunday morning there is service at 10, after which comes a class for Confirmation candidates, followed by dinner (often then I have to feed some who come from a great distance, and have no where to go), so you see expenses are by no means few, but I cannot turn them away, as by this means I frequently gain souls for Christ.

At 2 p.m. comes a class for Baptism candidates, and soon after 3 Sunday School.

The evening I reserve for going after the wild Malayta, and [28/29] recruiting them for School. I often walk miles. I have by God's blessing gained so many that the School has no lack of scholars, in fact they increase weekly, which makes me the more regret want of means to carry on.

It seems a thousand pities now that the School is as it were in the height of its prosperity as to attendances, &c., that for the lack of £80 the work should cease, as I feel sure that Bishop Wilson will send the £70 as long as he is able. Can nothing be done at home?

I thought I would let you know--because I know what interest you always took in the work, and indeed I feel always that I have to thank you, not only for first putting it into my head to do this work for God, but also for encouraging me to build the School by your first donation towards it.

Signed,

MARY GOODWIN ROBINSON.

The following details of the attack on the Austrian Expedition at the Island of Guadalcanar, are taken from the "Star," a Sydney paper.

This attack and the reprisals consequent upon it, will not render Hugo Gorovaka's work more easy.

But I do not anticipate that it will have any great effect upon him, beyond the general excitement that it will cause. For the bush tribes and those on the sea shore had in most cases very little in common, and the attack appears to have been made far up in the hills, apparently three days march from the coast.