After finishing his very hard work in New Zealand which is chronicled in "Things to be thankful for" the Bishop went over to Australia and spent most of May in Queensland. He was anxious to see with his own eyes the state of the labourers there, and also to find out what could be done to utilize them for the service of the Mission when they returned to their own homes.

The whole subject bristles with difficulties.

The first and perhaps the greatest is the political question. There are two great parties in Queensland. (1), The Labour party which holds that all Queensland should be retained for the white man, and resents the introduction of coloured labour. (2), The Planters party which declares that white labour cannot be usefully employed to work sugar in the tropical districts, and therefore urges the Government to allow it to "recruit" labour which lies in the Islands of Melanesia. For the Mission to steer an even and impartial course between these two factions is very difficult, and complicates a question which is difficult enough in itself.

The second difficulty arises from the fact that the Melanesians are imported into a Colony which has its own settled Ecclesiastical organization. How far, if at all, ought the Mission to go in seeking out the men who are taken away from its own field of work and brought to the shores of Queensland simply for the benefit of Queensland itself. It will be seen that the Bishop presses very strongly on the Government, the duty of providing for the education of the people thus imported, and it is clearly the duty also of the Queensland Church to reach as far as it can with its scanty means, and in its vast area, the people thus brought within the reach of its ministration. But as the large proportion of the labourers who are brought to Queensland, return sooner or later to their own homes, the Mission may rightly try to gain some hold on these, and by utilizing and subsidizing the work of the existing schools and perhaps by creating other centres for the same purpose, form links which may draw the labourers about to return into contact with the Mission and send them back to their own Islands ready, either to work heartily with the teachers trained at Norfolk Island, or else to act as pioneers in new districts.

The third great difficulty is that of language.

In Queensland the labourers speak a queer tongue called Pidgeon English, which is so different from real English that an Englishman can barely understand it. In some of the Queensland schools the teaching is given in pure English, but Mrs. Robinson who has perhaps the most successful school in Queensland advocates the use of Pidgeon English as being more understood by her polyglot pupils. But this leads nowhere. It has no literature, and a man taught in this "lingo," has only his unaided memory to go on, if he attempts to reproduce what he has learnt among his own people and in their own dialect. The difficulty is further complicated by the fact that in Figi the labourers learn Figi, and also talk a similar barbaric English. The Bishop does not appear to have grappled with this difficulty at present.

These notes will, the Editor hopes, make the Bishop's letters easier to understand.

The first is from Townsville, dated May 8th, 1895.

You will be anxiously awaiting news, I know, of my Queensland trip. I have reached the Northern limit, now, and am trying hard to knock up a scheme of work. The Government and Planters have given me a hearty welcome and all wish you could have come long ago * * * * *

[4] There is no doubt that generally speaking the labourers are well treated here, having abundance of food and clothing. The pay also is good, running up to £36. In Mackay district the average pay is £21, at Bundaberg £14. I shall recommend the Government if they ask me, to fine men who serve grog to natives £50 or a year's imprisonment, and to punish severely Chinese who sell them opium. These are the two greatest evils to be met with.

Farmers and Planters are beginning to see the use of schools. Most boys are wanting to learn and will walk six miles to school of an evening after work. This the planter objects to, saying that it tires the boys, and that they are not fit for work the next day. The boys work hard from sunrise to sunset. It seems to me that no objection should be raised to their receiving instruction every night. Herein lies another bone of contention. Many farmers will agree to two or three nights a week, but not more, because they say that on school nights they go to bed late. The great want is Schools, and the effect of a school in a district is most remarkable. The farmers round it have labour in abundance, and often at a cheaper rate a boy taking £20 instead of £25, so that his work may be near a school. Moreover the ruffians leave the neighbourhood, and you know what that means when the ruffians are Malanta. Life is rather a curiosity when there are 500 Malanta boys in your immediate vicinity.

There is one thing evident we must spend some money here and it will pay us to do so. I think I shall take Clayton, a Deacon of Bundaberg on the Staff. That district guarantees £200 per annum. Pritt, of Herbert River I must also take on and I must give him £100 per annum. He will work at Mackay, making a small college for time expired boys, and serving schools throughout the district by them. The planters have promised a £100 a year and a house and ground. Thus he will have £200, &c. I should give Mrs. Robinson £150, and possibly £50 to a man on the Herbert. This would make £300 a year from the Melanesian Mission altogether, but I believe we shall raise this money in Queensland, if not this year certainly in after years. Tasmania also wishes to help us here. We have a grand opportunity.

My line about the traffic is I believe yours. In effect it is--Queensland may be a good Public School for Melanesians, and the traffic may do good to their characters, but in the absence of schools and the presence of grog and other temptations, evil is now the result of it. Encourage schools, civilize and evangelize the people, and we shall not object to it.

CECIL WILSON,

BISHOP.

Wire just arrived from Brisbane official saying that 2 out of 6 Malanta men are to be hanged for the murder of an old white man near Bundaberg. The crime was brought home by the seventh murderer turning Queen's evidence. All were sentenced to death. I wrote and explained as far as I knew their Malanta ideas of justice and fairness, and represented the execution of 6, and pardon of the Queen's evidence as incomprehensible to the Malanta mind. I also told of the result of the trial of Bowers murderers. Something may have come of my visit here already."

The Bishop writes again from

TOOWOOMBA,

QUEENSLAND,

MAY 20TH, 1895.

"I have written you very little about Queensland business, because it was quite useless to write home any impressions when I had only half seen what was to be seen. Now I have finished, so I can tell you what conclusions I have come to, and the gist of what I tell you. I have written in a memorandum to the Queensland Government. I have seen M. Nelson, the Premier, and. M. Tizer, the Colonial Secretary, and a good many other officials and have expressed my views.

[5] The Government is unintentionally allowing two wrongs to be committed against the Islanders. It makes no effort to civilize them while here, and it also depopulates the Islands.

I. Want of Civilization.

(i).--Any amount of liquor is bought by the natives from the "mean whites." The fine on conviction is only £5, and is laughed at by the dealers in grog. These by the way are not generally publicans, but go betweens, who buy a bottle of whiskey, divide it into two, adding water to each portion, and then sell each for 10/- to an Islander.

2.-The Chinese sell opium and opium charcoal to them.

3.-Education is discouraged (as shewn in first letter. ED.) because boys are apt to walk long distances to school and are tired before their work next day.

I visited two Malanta boys in Brisbane gaol condemned to death for killing an old white man in Bundaberg. They had been in Queensland for six years, and had attended school for 3 mouths, and knew scarcely a word of English. They were hanged this morning, poor fellows, as ignorant as dogs.

I have made a point of saying that 6000 boys go back to their Islands as they came, perhaps worse.

I. Depopulation. Captains receive boys from any Island and think nothing of depopulation. Browning tells me that there are 4000 people in Florida. I find that there are over 500 boys from Florida here.

2.--The long voyages of labour vessels, lasting four months at least, sow the seeds of disease. Hence the very high death rate whilst in Queensland. I urge the Government to do the recruiting themselves in their own ships, and to have an Imperial or Colonial Officer stationed in the Islands to protect islands from depopulation, and to collect men desirous to 'recruit' that the voyage may be hastened.

3.--To prevent women leaving their husbands.

4.--Also that times of sailing be well advertised, and the dates of expiration of service made to coincide with them. Boys often wait and wait for a vessel to return to their homes in, and have to sign on again for want of money.

The Government suggested forbidding recruiting to Malanta because of their ferocity there. I told them that from our point of view, the only thing to be said for the traffic is that they take wild islanders as well as Christians, and they might, as you say, turn them into good stuff if they would only teach them while here, but even this possibility is dear when the high rate of mortality is considered.

My wish has been to get a look at the traffic on both its sides, and to bring some good out it. Hence my recommendations to the Queensland Government officials, which, if adopted, might do something to stop the depopulation. I have recommended fine of £50 for selling grog or opium.

There is a large South Sea Islander's Fund amounting to perhaps £30,000. This might be used to subsidize any schools that might be started. Without such help I see no chance of covering all the districts. There is not the remotest possibility of the Traffic lasting another five years. My hope is that it may last as long in order that we may get some good out of a traffic which has done the Islands much harm. If schools were started soon, the boys would crowd to them.

How we shall get enough teachers I do not know. At present we have Clayton a Deacon at Bundaberg, and Mrs. Robinson at Mackay, and Pritt on the Herbert. My scheme is to start Colleges (like St. Barnabas) on a small scale at Bundaberg, and perhaps at Burdekin, where a few time expired boys may be trained to teach the rest, but this will take time, and perhaps the trade will be over first. I am not going to spend much money on the work. It is too precarious. The Primate has allocated £450 from the Self-Denial week to this particular work, but to give so much would be to rob the rest of the work, and I shall get a dispensation from him. I have promised to help North Queensland by giving £200 to meet £200. This will keep Mrs. Robinson and Pritt going. The Planters will help Clayton and give him £200, so really if we give £l00 this year it will be enough.

[6] The only complaint the boys make is about the lack of schools. A Lakona boy said to me, "This is an evil land, there are no schools!"

I have been running about until I am sick to death of it and have had very little time for writing. Forgive me, but I am fagged out.

In a short note from Sydney, dated May 25th, the Bishop thus sums up.

The enclosed slip will shew you what my feelings have been.

If they take our boys from Islands where there may or may not be schools, they must educate and civilize them. I mean the Community, not the Government.

There is a large sum belonging to the South Sea Islander's Fund, about £30,000 coming from the boys own savings in the Saving's Bank--i.e. those of boys who had died. This might be applied to subsidize Colleges and School. The Board of Mission will most likely help us also.

I have not made myself responsible for the Islanders. I have agreed to work among them, but have tried to spend no more money than will be given for this purpose. At present my liabilities are £200 a year to Queensland, and this grant may raise a great deal more.

If Brittain works at Mackay, which possibly he will not care to do, we shall have Rev. E. Clayton at Bundaberg; Rev. A. Brittain and Mrs. Robinson at Mackay; Rev. F. Pritt at Burdikin; M. J. Fussell at Herbert River.

Young fellows keep volunteering to go. I promise £100 a year if I think it can be raised in the neighbourhood.

I leave by the "Orlando" with Admiral Bridge, next Tuesday.

After Bishop Selwyn resigned, in 1891, the Melanesian Mission was left for three years without a Bishop, with a very small staff of white clergy, and so poor that the Southern Cross could only make two voyages in a year instead of three; the native teachers and their schools during this time of "orphanhood" were left more to themselves than had for many years been the case. What was the result? Did the work go back during the three year's interval which preceded the appointment and arrival of the new Bishop? No; not a school had been given up, but many had been started; there were six new Churches ready for consecration, and 525 men and women were brought to the Bishop for confirmation. Facts such as these surely prove the soundness of the work that has been done in Melanesia.

Sir John Thurston, as High Commissioner of the Pacific, made a cruise in H.M.S. "Ringdove" among the Solomon Islands during last year. Much useful knowledge was gained by him, and much useful work was done. We believe that great benefits to the Islanders will result from his visit. In Rubiana (New Georgia), one of the worst and most savage of the Solomon Islands, a Court was held under His Excellency's presidency, and a white trader was called to give an account of his doings on the Island. The High Commissioner treated [6/7] him with a strong, firm hand, much to the delight of the native chiefs, who, when judgment was delivered, were so astonished at the white chief's justice, and the solemnity of the whole proceedings, that their leader stepped forward and wrenched the ghost's head from the prow of his canoe, and gave it and his war spears to Sir John, saying. "Take these: head hunting is over for ever in Rubiana;" and all the chiefs assented, and said that head-hunters landing on their beaches and asking hospitality on their way to the raids should be refused and driven away. A door seems to lie open into Rubiana.

After a tour round the coasts of New Zealand, lasting from January 17 to April 5, the Southern Cross returned with Mr. Brittain, the twenty-two Melanesian boys, and many recruits to Norfolk Island. Most of the important towns and cities in the Colony had been visited. The Bishop had preached thirty four times, and lectured and spoken twenty-one times more. Mr. Brittain's list of engagements fulfilled was equally long. The greatest kindness had been shown to the missioners and the boys in every place visited; much interest was aroused and help promised. In Christchurch the Rev. W. Ivens and Mr. E. J. Buchanan--the former an old Christ's College boy, the latter of the High School--joined the mission staff. In Napier Dr. J. D. Williams, joined us; he is brother of another recruit, the Rev. Percy Williams, of S. Sepulchre's, Auckland. In Wellington, Miss Lewis was accepted on a six months' trial. Meanwhile the Rev. R. Paley Wilson and Miss Firmstone (sister of Mrs. Browning, at Norfolk island) had reached us from England. The ship returns, therefore, after her tour with seven new missionaries--five men and two ladies, a considerable and most valuable addition to our little staff.

As we look back on the week that has just closed, it stands out in our memory as a singularly happy one. From the first hour to the last, the spirit of willing self-denial, and cheerfulness in giving, pervaded the whole island.

Not only did our Melanesians work with heart and soul, that they might have the means of helping those who are still "walking in darkness," but our friends of the Norfolk Island community threw themselves heartily into the proposition that they should do some special work needed at S. Barnabas.

The whole of the work involved in re-shingling the roof of Mr. Browning's house was accomplished in four days. Upwards of fifty men came forward to help. Cutting down the pine, splitting the shingles, carting them from the bush, clearing off the old roof, and nailing on the new, gave a variety of hard work to them all; and it was interesting to see the toilers of all ages, from the youth to the fine old man of "threescore and ten," each doing his share of the work with all his might.

The women, too, were as willing to help as the men. Some brought specimens of their handiwork, bags and hats beautifully plaited to be sold for the benefit of the Mission. Others made clothes for our scholars. About sixty garments were given out, and the work was [7/8] very neatly done. This does not include the help given also just as willingly at two or three sewing classes, Mrs. Thorman's being the largest of these. Some who were not in time in applying for the clothes, earned something in other ways for the offertory on S. Andrew's Day in the town church, which was also devoted to the funds of the Melanesian Mission. The young children, too, gave their help by doing the housework, while their mothers or elder sisters sewed, and the glad faces when the work was brought in testified to the blessing already felt in the heart of each worker.

But we must turn to our Melanesian workers, and tell how this Self-Denial Week affected them. We talked the matter over at our afternoon tea on the Wednesday before, as we were looking through some of the Bishop of Tasmania's spirited leaflets. We felt that if there was not very much to be done in the way of giving up luxuries among ourselves, we must give, "every man as he purposeth in his heart;" but with regard to our boys and girls, what could they do if they wished to help? We heard that the boys were to have the offer of extra work in their play-hours, by which they could earn a little money for the S. Andrew's Day offertory. This was a practical idea for the girls too. So, with the consent of the Archdeacon, we ladies summoned a meeting of the girls after evensong on Saturday.

Mrs. Colenso explained to them the plan proposed, and also told them a little more definitely than they already knew about the object of this Self-Denial Week. They listened with great attention to her address; and when she put it to them whether they were willing to give up their play-time for four afternoons, and work hard in the fields to earn some money to help to send teachers to the heathen of Australia and New Guinea, the response was unanimous: "They would like to do it." Our hearts gave thanks, for there was no sham about it. And more and more our enthusiasm rose as the days went on, and our children's zeal never flagged from that first moment. So, before the 25th Sunday after Trinity dawned in Norfolk Island, the petition in our collect was being abundantly answered, for the wills of God's people, old and young, rich and poor, white and black, were already stirred up to carry out His will.

The lad with the loaves (S. John vi. 9, Gospel) helped some of us all through the week. At Sunday School, Bible Class, and Mothers' Meeting he was a prominent character. Sunday was a very happy day, all who were able making a special effort to add something to the offertory from their tiny store. The little white children, too, pleaded to give their "own money" on that day. Two missionary prayers, translated by the Archdeacon, were used in the service and throughout the week, and were most helpful. On Monday the work began. After writing school, at 3 o'clock, boys and girls went off to their respective fields of labour, to cut down the wild tobacco and the weeds. The sun was hot, some backs were aching, and many little brown hands and white hands were blistered before the hours of toil were ended; but they worked bravely on. No work was proposed for the boys on Wednesday, the usual half-holiday, so we suggested to the girls also that they should rest; but as they would not hear of it, we all went down to the cemetery, and weeded there till 5 o'clock. All were at work again on Thursday afternoon just as heartily as ever. Truly, they [8/9] had not offered to the Lord that which had cost them nothing! In the evening the girls met once more at Mrs. Colenso's and each received a shilling for her work. Only little Carrie Huhu, our six-year-old baby, was content with sixpence, as she, of course, had not worked hard like the rest. St. Andrew's Day, I need scarcely say, was a glad one. At the early Mota celebration there was a good offertory, but the greater number gave their offerings after the evening service. Our offertory, including that on the preceding Sunday, amounted to not less than £12 18s. During this week ordinary evening school was suspended, as sermons were preached on Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday; and on Monday the Rev. H. Welchman gave the school a missionary address. St. Andrew's Day concluded with an English service in the chapel, at 8 p.m. at which many of our Norfolk Island friends and helpers were present. The sermon was preached by the Rev. T. P. Thorman. Saturday was a restful one to the school. The work was over, the week was ended, the result was real, the effect-who can tell? But I think we have all realised in some degree how blessed a thing it is to be "workers together with Him." A.C.

Our readers will be sorry to hear that the Southern Cross has been giving a good deal of trouble. Coming back from the trip to the south the vessel got into a very heavy gale off Cooks Straits, and strained herself badly. When she got to Auckland, a great deal of work was done strengthening the vessel's forehead, and making the deck houses tight, and some ballast was taken out. She then sailed for the Islands with a heavy load. When they got into rough water, everything began to work again and they found that she was leaking badly. They had to keep the "donkey" at work constantly to keep her free, and though Captain Bongard managed to reach Norfolk Island and land his passengers and stores, he had to go back at once to Auckland for further repairs. This made her very late on her return to Norfolk Island, but we have heard that she reached Norfolk Island again towards the end of May and then started on her Island Voyage.

Captain Tilly reports that one of the timbers at the stern seems to have started, and that she can be repaired temporarily at a cost of £40 to do her year's work, and then can be further strengthened afterwards when she returns. It is vexatious that she should need this.

Rev. R. P. Wilson writes on 17th March, to tell of his safe arrival. He managed to catch the "Birksgate" at Sydney, and so got down direct.

Of his landing Dr. Welchman writes. "It was horribly rough, there was no landing at the town, and at the Cascades it was so bad that all the men hung back. You know what that means. At last four of them volunteered if Fairfax would steer. They went out, but it was so bad that they doubted if they should get back again, and arranged with the Captain to pick them up if they upset. They got in all right, but as R. P. Wilson landed, a big surf came up as he reached the rock, and his foot slipping, wet him through and he got down into one of the holes. Except for the wetting he was none the worse, and we soon got him dry clothes at the Mission. (His own went on to Figi). Everybody agrees that it was a dangerous experiment, and look upon him rather with pride for having gone through it. Just as with everyone else, he says he knew the danger, but never felt a queller, then calm behaviour inspired confidence."

Such is a Norfolk island welcome. (ED).

[10] Mr. Wilson says "Although I cannot do much, owing to my not being up in the language, I am settling down into the ways of the place and to the boys. I am not surprised at your love for them, they are delightful, and I am getting to know those in Brittain's house. We try to talk and I pick up Mota words and make them pronounce them, and then say them over to the boys until I get the pronunciation right, and am gratified by hearing a murmur of "we run," that's right

THE INFLUENZA.--Writing on the 20th March, Dr. Welchman says we are in a state of misery again in the "Vanua." Another cold has got hold of the place; not so bad as the Christmas one, but quite bad enough, and our houses are just full of boys lying down.

On the 14th of May, he adds. In my last I told you I think about the boys being ill. Since then matters developed very much indeed and we had to take strong measures. Charley Sapi and Melkona were the two boys who were so seriously ill, but more came and more and every house had its contingent of boys needing night nursing. We took possession of Brittain's house and gathered the sick in his big room. We divided the day into watches, and organised a nursing staff with a proper rota of white and native helpers, and gave Miss Farr a hospital dietary to supply. We nearly drove the Island mad hunting for eggs. At first we consumed nearly 50 a day, but we had our hospital full in its twelve beds, and it was a question which was the worst. Most of it pleura pneumonia and ague of a remittent type, with temperature either persistently 104° or 105°, or varying from 95.5 to 104°. We had a lively time of it. One boy we gave up for three days as hopeless, but plied him hard with food, and now he is running about. Thank God we lost none of them. The only boy who died was Silas Sani who was a year dying of consumption, and was not affected by this new epidemic. Our nurses changed every four hours, and all were as good as gold. Not a "leasag" or a "mero" among them, though it went on for days. To add to our discomfort we expected the Southern Cross daily and we decided to send some one on board as soon as she arrived, and forbid any of the New Zealand Tourists landing, thus putting the healthy in quarantine for a few days in hopes of saving them from infection. You must know that the whole white Island was suffering. Some very severely. However God ordered it otherwise, as the Southern Cross arrived, leaking badly, and after landing her passengers and stores, had to return at once to New Zealand. (April 11th).

Dr. Welchman's letter will show how bravely and successfully

the Mission workers fought against this terrible epidemic. God's

mercy was great, but no one who has experienced such a crisis,

can imagine the tremendous anxiety and labour which it entails

on the scanty staff at Norfolk Island. The only nurses available

are the members of the Staff themselves aided by the boys who

always work most willingly. School and farm work goes oil as

usual, and yet the men who superintend these have to give up

one watch at least of their night, to the incessant care of the

sick, add to this the difficulty of obtaining the requisite food,

as the egg incident shows, and it will be seen that Dr. Welshman's

"lively time," meant a fearful amount of responsibility,

anxiety and work. This anxiety however did not prevent Dr. Welchman

doing something for himself, which may have far reaching consequences

for the Mission.

,

[11] In the same letter he announces his engagement to Miss Helen

Rossiter, who he hopes to take back with him next year to work

with him at new station at Siota. Miss Rossiter has been working

for sometime as a volunteer at the Mission and was last year

put on the staff by the Bishop. She is the daughter of Mr. Thomas

Rossiter who came out many years ago as the Schoolmaster of the

Pitcairn Community, and has known the Mission all her life. She

brings to the Mission a brave heart and great sympathy in its

work, and beyond this a skill in every kind of woman's work which

cannot fail to be of the utmost use in training and raising the

women of Florida. Dr. Welchman goes down now to prepare the place,

and hopes next year (D.V.) to come up to be married.

The Editor who has known Helen Rossiter from a child and who owes his life to Dr. Welchman cannot help asking all his readers to pray that this union which is not devoid of self -sacrifice, may bring to them both that blessedness and usefulness which they anticipate from it.

___________________________

Having left England on the twentieth of April, 1894, I reached Auckland just in time to be consecrated on S. Barnabas' Day by the New Zealand Bishops in S. Mary's Pro-Cathedral. From June 27th until September 10th I was at Norfolk Island, spending my time at Mota, and picking up as I could the reins of the mission. During this time I confirmed thirty-four boys and girls. Many of these were ready to begin work in the islands, and were only waiting my arrival that they might receive Confirmation prior to returning to their various islands and fields of work. On September 10th we left Norfolk Island, and, with a fair wind, sailed for the islands. We had on board Mr. Comins, who was going to act as my pilot and chaplain; Messrs. Brittain and Forrest; the native clergy, George Sarawia and Henry Tagalad, and a good many boys, many of them with their wives. We were fifty-seven passengers in all.

The first land reached is Walpole Island, a home for seabirds and nothing else. Keeping to the east of the Loyalty Islands, where, in Bishop Patteson's days, the Mission had stations, we visited the New Hebrides Group, the southernmost islands of which are now worked by the Presbyterian Mission, the three northernmost only remaining with us. It was in this group that I made my first near acquaintance with South Sea Islands. We dropped anchor at the north end of Araga (Pentecost). The water was so clear that one could see almost every stone at the bottom, although we were in something like ten fathoms of water, and great fish swimming about picking up the scraps which soon began to fall. The shore, like other islands in these waters was wooded right down to the beach. Even the cliffs were disguised with thick foliage. The heat was tremendous, there being no wind, and the sea reflecting the sun like a mirror. Eight teachers came on board. They were nicely dressed in Norfolk Island clothes, i e., trousers and shirt with straw hat. Their people were scantily clad--just a [11/12] loin-cloth, and a string round the neck carrying a pretty shell, and very often a pipe. They had had a good deal of trouble, dysentery having broken out and carried off many, amongst others the chief. The latter's death might have made trouble. People had talked of fighting, but had done no more. About twenty men and boys came on board. They seemed quite at home, sitting solemnly on the hen-coops, looking so cool and healthy in their scanty clothing. There are seven schools in Raga, and about four hundred people attending them, 250 of whom are baptised. The influence of the Mission extends far beyond the school village. We were told that lately a man had returned from Queensland with a Winchester rifle, and had tried to get up a war on the heathen side of the island in order to test its powers. However, the heathen said, "No; the school people do not fight, and we do not mean to." The rifle was going cheap after that.

We visited Opa and Maewo, and then put down Mr. Brittain at Opa, with John Pantutun, promising to return in two months' time; and we did so to a day.

We ran down to Banks Islands in a night, reaching the first of the group--Merelava--at daybreak. It stands up, a great volcano, extinct now, 3000 feet above the sea, clad to the water's edge with vegetation. Here and there a patch on the mountain side is cleared for a garden, the brown earth making a striking contrast to the green foliage of the trees. We went on shore and paid the teachers, and I made friends with the people. A Fiji recruiting (labour) vessel was there before us. One of her hands, a Merelava man, had deserted on reaching his own island, and nothing would induce him to return to the ship. This was my first sight of the 'labour traffic.' Sir John Thurston, Governor of Fiji, told me when I met him later, that he was putting a stop to it in Fiji, and that this vessel, which we saw was returning men to their homes, and not taking them up

A great wave of church building fervour was passing over the nine Bank's Islands. Three new churches were complete, and I consecrated two of them, at Ra and Ureparapara; the third I was to have consecrated on the return journey, but it blew a gale, and we could not land. Some good school buildings had also been erected, notably one at Mota, capable of holding 400 people.

Mr. Cullwick was having some trouble on account of tendency on the part of a few men in different islands to return to their own customs of the Salegora and Suqe. This matter is dealt with in Mr. Cullwick's own report. Christianity has now become almost co-extensive with these islands, very few heathen remaining, and those only in scattered districts where it is impossible to provide teachers, although could they be found they. would be welcomed and rejoiced over. Here, if anywhere, the Mission ought to be self-supporting. I suggested frequent offertories to George Sarawia and the teachers in Mota. They discussed the point, and decided to have a monthly offertory throughout the island. They seemed also to see their way to the manufacture of large quantities of copra. To them, and to all teachers throughout Melanesia, I have suggested that the native teachers should he paid out of the offerings of natives; the white clergy, the ship, Norfolk Island, and other institutions of the sort must still be supported by the Church in the colonies and at home.

[13] From the Banks' Islands to the Torres is a short run, but there was no wind, and our little engine came in usefully. There are four small islands in the Torres' Group. One of them, Lo, is entirely Christian; Tugua is crying out for teachers, and its first converts were last year baptised. On Hiu and Tugua we have received grants of land for schools which the people are ready to build if we will send teachers. Mr. Robin, who is in charge here, is in great distress for lack of helpers. His people are much in earnest. They had built a very fine new church, which I consecrated; they had also given up a certain Suqe custom which would prevent them from becoming communicants, and 44 of them were presented to me for confirmation. On my return visit the last heathen in Lo put themselves under instruction. Here and elsewhere I told the people that as they were a part of the Church of Australasia, they might, if they liked, take part in the special self-denial effort for Foreign Missions, in which the Church engaged in the week following S. Andrew's Day. On my return from the Solomon Islands the natives gave most liberally. They brought in from Lo more than four hundred war arrows, many bows, baskets, food knives, and curios; in the Banks' Islands quantities of baskets had been made, and were given for the alenga (gift); in the New Hebrides many boat loads of yams, taro, and cocoanuts were sent on board with the same object in view. The islanders said "Take these and sell them in New Zealand, and that shall be our gift." I believe that about £150 has been realised at home and in the colonies by the sale of their contribution. Until now the Church in Melanesia has been so far self-supporting that it has built its own churches and schools--a considerable gift of time and energy. Surely the sincerity they have shown lately proves that they are ready to take yet another step forward, and support their own teachers. We shall see.* [Footnote: * I do not quite see how.--ED.]

On the festival of S. Michael and All Angels we entered Santa Cruz waters, and I felt that a more suitable day could not have been chosen for an entrance upon scenes haunted by so many solemn memories. Here it was that Bishop Patteson, Joseph Atkins, Fisher Young, Edwin Nobbs and Stephen Taroaniaro laid down their lives for their Master whilst engaged in the Mission work. And still Vanikoro, Tupua, and some of the Reef Islands are untouched. Santa Cruz has only three schools; and the Reef Islands, such as Nukapu, only two. We put down Mr. Forrest at Nelua, and on my return on All Saints' Day I went ashore to him and consecrated a very fine new church, large enough to hold 300 people, or more; and I baptised 15 adults, mostly men, and confirmed 16, again mostly men, great strapping fellows, with large shell breastplates and nose rings, but with an air of perfect devotion and reverence. I slept a night at To Motu. A wild, excitable lot of people they seemed to be; yet the Kingdom of Christ is slowly gaining ground even amongst these braves of Santa Cruz. But I am puzzled to know how we are going to convert this group. Grand men of enormous physique, as they appear to be, these Cruzians cannot live in Queensland nor in Norfolk Island. Their lungs give way in any climate but their own. It appears to me that we shall find that we must set up a college in Nelua after the old pattern of Bishop Patteson's Kohimarama in Mota, and bring the natives from Santa [13/14] Cruz and surrounding islands there for their instruction. But will they come? Anyone will leave home for Norfolk Island, but it is quite another thing to leave home for Nelua, or any such place within the island in which they live. The Santa Cruz problem is a most difficult one.

The first island of the Solomon Group we touched was Ulawa. On one side Clement Marau, one of the best known of our native deacons, lives; on the other, where we now landed, Johnson Telegsem has got together a school during the past two years. Clement has worked in Matoa for eleven years, and has a large Christian population round him; Johnson's work is only just beginning to tell. He has done exceedingly well. He worked for a time with every discouragement, and at much risk to himself. But now the obstacles appear to have cleared away; the neighbouring villages of Moota say that the school was bringing good to Ulawa and not the plagues that they had anticipated, and it seems likely that they would welcome teachers. The heathen of the school village were on the point of "wiping out" the Christians, having a grievance against their chief who was under instruction. In the early dawn, as they came up in line, they were confronted by Johnson Telegsem and Marau, who had been fetched in the night, and they listened to reason, and went to their homes. On my taking Telegsem away the heathen said that if we would bring him back they would all go to school. Clement is a most striking man. Let those who want to know him read Dr. Codrington's translation of his Autobiography--"A Melanesian Deacon," S.P.C.K. I confirmed his first confirmation candidates, eleven in number, after eleven years of work. He has been patient, and he now sees the fruits of his labours. Matea, his station, is no longer a village, but a town, people from all over the island wishing to live in peace and within reach of his teaching. At Ugi, the next island we called at, we are doing nothing. San Cristoval, with 20,000 people, perhaps had six schools. I believe that a white missionary settled here could gather in the whole island. We carried away old Bo, chief of Heuru, for a fortnight's cruise. Most likely his village would form a good base of operations. From San Cristoval we sailed some 35 miles to Saa, at the south end of Maleita. We found the little Christian party holding its own against all the weight of a great, fierce heathen island. Joe Wate, the teacher in charge, has taught there for twenty years. He has now 120 men, women, and children attending school; and what faces they had! Having seen them I can imagine the quiet, patient devotion to Christ of the Christians in the days of Nero. "They may wear loin cloths and be Christians if they like," runs the heathen edict in Malata to-day, "but if they do they may be treated as pigs, and not as men." And yet even here the darkness is giving way. From Roas, five miles north of Saa, we picked up two boys, the villagers having set them aside before our arrival, and having stayed from their gardens that they might in a body hand them over. Two boys Oiu and Samo are holding on grandly at Port Adam. They have no school, but they are witnesses for their Master in their daily lives. To go from Malanta to Florida is to go from darkness to light, almost from hell to heaven. Out of 4000 people there 3500 are Christians, and their reception of us fairly surprised me. I felt that we had suddenly fallen amongst friends, and men like ourselves. The hearty grip of the hand, the [14/15] boyish joy when they discovered a friend on board:--they were Christians, and good Christians, and one felt it. I went all over the island, and saw most of their twenty-eight schools; I confirmed 118 men and women, and consecrated John Takesi's new church in the swamp of Gumelaghi; and I marvelled that this could be the Florida which in 1880 cut off and killed Lieutenant Bower of H.M.S. 'Sandfly,' and was considered the worst of the Solomon Islands. There are now in Florida sixty-six teachers, many of them men of great intelligence. Their only books are parts of the Old Testament, the New Testament, Prayer Book and Hymns. Are these enough? Can men teach, and teach for five or ten years, successfully without further books to help them? When our new S. Luke's College, Siotu, in this island is completed, the missionary priest in charge will be able to hold 'Quiet Days,' for teachers there, and much good will be done. But the idea seems to be growing in the Mission that we should teach the boys at Norfolk Island more English, and try to open up some of our simpler literature to them. But meanwhile for this generation I believe we should print a few small books in the Mota language.

We reached Bugotu (Ysabel). This used to be the happy hunting ground for New Georgia head-quarters. For the years the people have enjoyed immunity from their attack. Soga, the chief, and Dr. Welchman's friend and ally, came on board in coat and round hat to pay his respects. When I heard that he had paid up the fine that had been levied upon his son for misbehaviour I admired him more than ever. He is tall, thin, with an intelligent face, and good manners; in age about fifty. He and the deacon Hugo work admirably together. Their village of Sepi is a marvel of cleanliness, with a kind of esplanade on which the people congregate, a large garden made and kept by the labour of wrong-doers, who are set by Soga to do this public work to atone for their misdemeanours. There are 1200 Christians in the island, and 1500 under instruction. From Bugotu, Dr. Welchman is pushing on into the "regions beyond." He hopes to visit New Georgia in August, and the neighbouring islands. He has decided to spend a year, if his health permits, in the group, taking charge of S. Luke's, Florida, during the summer months, in Messrs. Comins' and Browning's absence, and carrying on a hospital as well as a college. May GOD bless him, for he has indeed a great task before him!

We reached Norfolk Island on Advent Sunday (December 2nd), having with us no less than 114 native scholars and teachers. I had confirmed during the cruise 490 men and women; consecrated five new churches, and dedicated many schools; baptised many and seen many baptised by the other clergy; and on that first day of the new Church year we were able to join in one of the heartiest services that I ever saw to thank GOD for His mercies to us during the year which had just closed.

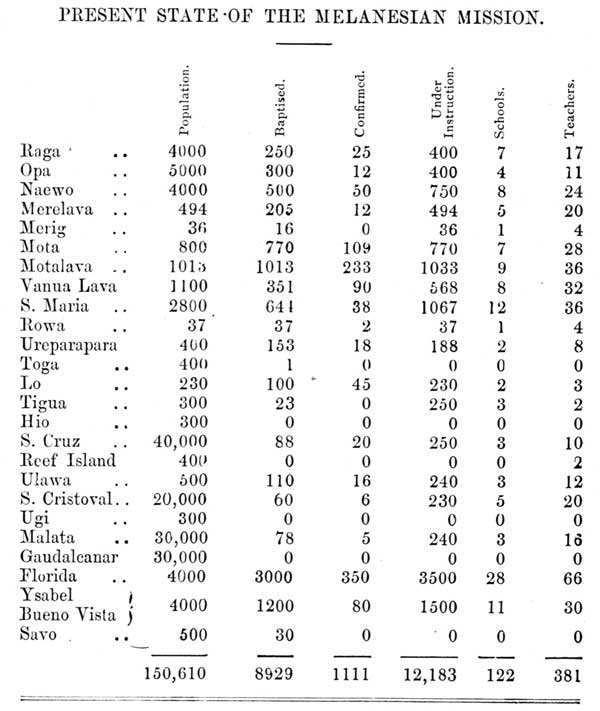

So ended my first voyage. We could not do all that we should have liked to have done, but we did much, and we praise GOD for giving us His grace and help which alone enabled us to do what we did. Generally speaking, I was astonished at the progress the Gospel has made in the Islands. The figures giving the "Present State of the Melanesian Mission " are compiled by the clergy in charge of the various districts.

[16] The Bishop of Melanesia recommends to the readers of the ISLAND VOYAGE the CYCLE OF PRAYER FOR THE MELANESIAN MISSION, which gives a short history of the work upon each of the islands, and sets aside one for every day of the month as an object for prayers. It may be bought of Rev. George MacMurray, Auckland, N.Z., or from Miss Wilson, Gatewick, Esher. Price 2d.

The SOUTHERN CROSS LOG is a new Melanesian periodical for New Zealand and Australia. It is edited by Canon Calder, Auckland. Monthly. Price ld.

This year my round of visits commenced at Merelava, and a very cheery beginning it was, The new church was awaiting the completion of the interior, which had purposely been deferred for what help could be given during my visit; it being the desire of everyone that the building should be made as worthily representative as possible of the work which has been done here. As soon as I got myself and belongings up to the village, the preliminary work began, and went on far into the night. The next day messengers were despatched in opposite directions round the island to levy contributions of boards for the seating, each school district to supply as many as they could adze in two days. A very hearty response was given, with the result that before the end of two days the seats were being fixed as fast as the native craft could work.

In the meantime all the owners of canoes were impressed for the purpose of obtaining coral and sand. For both these Merelava is very badly off, and to obtain them a journey almost to the other side of the island has to be made. The day happened to be a very favourable one, and quite a fleet of small canoes with my boat set out for the only place in which our hopes were centred to supply us with lime. Unfortunately, we were doomed to disappointment in this particular; the sand was of a very coarse description, and the only procurable coral stone was very inferior. We returned, however, well loaded, with the hope that something might be done, and the same day everything was carried up to school village. The lime was not a success, after all the hard work and trouble bestowed upon it, but the people did not allow the disappointment to damp their enthusiasm, and every effort was made to finish the interior during my very limited stay.

After most of the work had been done, I commenced the tour round the island, visiting the Matlewag school first. The people here appeared not to have lost any of their enthusiasm. The teacher, Joseph Qea, has stuck to his post very well. Although quite a junior, he has risen to the responsibilities of his position, and enjoys the full confidence and respect of the people.

The first evening of my stay, a touching scene took place after school was over. When the school was first started, a polygamist belonging to this part of the island attended with his two wives. After instruction had been going on for some time and the people were being admitted to prayers, the man was told that Christianity demanded the putting away of one of his wives. He said it could never be, and eventually left the school. At the beginning of the year a relation of his returned from Sydney, by name Andrew Tot, commonly known as Tommy Dodd. The latter, on his return, was very anxious to provide himself with a wife, and made known his wish to his relatives, who were nothing loath to accede to his request, being deeply interested in a big box that had accompanied him from Sydney.

[18] The much-married man approached the teacher with a solution to his own difficulty and also that of his relation. He said that he had been much disturbed in mind of late, and had felt the isolation from the school people. He stated his willingness to give up the most recently-married wife to his newly-arrived relative, and asked to be allowed to attend school once more. This was immediately followed out, and the woman was placed under the care of the native deacon's wife. The poor fellow found it very hard to stick to his resolutions and stifle his affections, making great lamentation over her departure, and going repeatedly to see her. This made everyone distrustful, as such behaviour was ominous of future complications. This man having given an assurance of his good faith, I told him that a public renunciation was necessary before the whole community, which he willingly agreed to do. After school was over he made a renunciation before the people, and strongly assured us of his earnestness. He accounted for his bad behaviour by saying the parting at first made his heart go backwards and forwards, but that now he was thoroughly prepared to make the sacrifice and give himself up to follow the new Law.

On my way to Legil we passed through Lewotnok, the district where the latest school has been started. The people were very busy with the new school-house; everyone seemed very heartily in the work. The levelling had had to be done to make the terrace for its site, and the same profuseness of labour which characterises the other Merelava buildings had been bestowed on the roof. The building is now completed, and a teacher from the place, who had just finished his education at Norfolk Island, has been sent to them.

The Legil people are always very bright and hearty. The man who generally puts himself forward as my cook had his usual stock of fat awaiting my visit, and produce his standing dish of yam fritters. I afterwards learned that he essayed to go to Queensland, and was arranging for his recruiting, when some of his creditors intervened and insisted on his staying to discharge his liabilities. They told him he could do so, if he liked, but must pay his debts first, and as this meant a week's dunning of his relations for money, he could not comply with the conditions of his creditors and had to stay. From what I heard afterwards, the recruiting party put it down to the teacher, and had a grievance against him in consequence.

At Fatmesi, the small community appeared very earnest, and gave us a hearty welcome. The teacher, who is the mildest of the mild, but who is very quick to rebuke wrong, had managed, notwithstanding, to raise the wrath of a man who had given a good deal of his time to the new schoolhouse. The latter appeared with knife and axe to wreck the schoolhouse, which he said was most of his work, and preferred a strong argument against being turned out. He was eventually appeased, and submitted willingly to what had been imposed.

On returning to Serei, the seating had been completed, and the immediate use of the building being imperative, we had our opening services on the following day, commencing with an early celebration of the Holy Communion. At matins the church was crowded with an enthusiastic congregation from all parts of the island, and their joyfulness found expression in the heartiness of the service.

[19] We sailed for Merig the following day, and were again successful in hauling up the boat to her snug little berth. The people were not quite so happy as usual. They had complained before about the Gaua people disturbing their tranquillity, and now they had another complaint. The year before, an old Gaua friend of mine, who continually excuses himself from becoming a catechumen, made a canoe journey with a protégé of his in search of a wife. This individual was already possessed of one but unfortunately she was afflicted with the infirmities of old age, and his garden and cooking suffered in consequence. This impressed him with the necessity of looking out for a more active partner. My friend, being rather high up in society, brought pressure to bear upon the Merig people in favour of his protégé, and they unwillingly gave their assent. We happened to arrive on the scene just as the negotiations had been completed, in time to prevent them being carried out, as the money consideration had not yet been disposed of. I was very much surprised at the good-natured, philosophic way in which they accepted the money back again, and we sailed along to Gaua in consort.

This time the grievance was about the Suqe, which is the way of obtaining rank. If anyone happens to have a good fat pig and a little cash, they are sure to be bespoken by some head man, who impresses upon the owner the desirability of buying a step in the Suqe from him. The Merig people are rich in pigs, which are coveted both at Merelava and Gaua. Many attempts had been made to beguile them away, and hence the complaint. They said, "We don't want our pigs carried away to Gaua and Merelava. It is much better to eat them ourselves and make ourselves merry under the new Law." While here, a great deal was told them about the new church at Merelava by my Merelava boat's crew, who did not understate its great success. This at once made them discontented with their small schoolhouse, which received a good deal of encouragement from myself. The site for a church was immediately pointed out, and the next day in our walks abroad the best trees for the pillars were marked. One thing only presents a difficulty: the ordinary creepers, used for string, do not exist on the island. They plait a string made from the cocoanut fibre, which finds a ready sale at Merelava for pieceing their canoes together, but this is very perishable when used for house-building purposes.

The only durable material entails a great amount of labour, and is made from the roots of the cocoanut, for which they begin to dig about 15 yards away from the trunk, and so follow it up until they get the full length. The tying-on of the roof absorbs a great quantity, and this makes it a considerable item in most places in estimating the cost of a building. Our Merig friends were very much gratified on our undertaking to supply them from Merelava or Gaua, but our promise remains yet unfulfilled, the ship being unable to call on her return. It was hoped that a confirmation would take place here, but the unusual weather experienced in the Banks' Group made it impracticable. My stay with my Merelava boat's crew was the occasion of great joyfulness, seeing so little of the outside world as they do. They seemed this year to have looked forward more than ever to the visit of the party, partly, perhaps, on account of the sad [19/20] news of the death of a favourite girl at Norfolk Island, which had to be told as I passed through in the ship, and partly on account of the class of catechumens awaiting Baptism. The sad news of the girl's death was a great shock. They were all very much overcome, the father especially so. He threw his arms round my neck as we stood on that dark landing rock, and wept out his grief, full, nevertheless, of Christian hope and trustfulness. "It is well," he said; "I leave her in God's hands." Out of the three taken from here to Norfolk Island, two have died, and their trustfulness seems to have increased rather than diminished. They pressed for a bright little boy to be taken to Norfolk Island, and as I could make no promise he wanted to follow me on my boat journeys round the group. The journey over to Gaua was miserably wet, and the perishable part of our belongings came off badly. We were delighted, however, to find enough water inside the reef to float us up to the school village, and soon forgot the discomforts of the voyage round a blazing fire.

The meeting of the year before, which resulted in a taboo being placed on guns and poisoned arrows, was still in force, and had been kept with spirit and determination by the head men; but, lacking the guidance of a leading spirit among the teachers, the method of exacting fines had taken an undesirable turn. In one village a man had misconducted himself, and instead of all the head men meeting and imposing the fine in the proper way, one of their number belonging to the next village sent his club decorated with a croton to exact a fine. This made the matter a personal one, and a little unfounded scandal arising at the other village, a decorated club was immediately despatched in revenge. The consequence of this was, that during my visit the whole matter had to be gone into again at a meeting of all the representatives, and the charge proving untrue, the fine was returned. It is exceedingly difficult to keep a district together divided by factions when there is no teacher who commands the respect and attention of the whole people. The teachers being Gaua people themselves, are identified with their respective schools, and their own conduct has often justified the people treating them thus. A strong man is very much needed here, not only to keep the people together, but the teachers. The latter are a sharp lot of fellows, only lacking in earnestness and stability. This makes it very difficult to find a man equal to the task. On the other side at Lakona, where the people and native teachers are dull, any good boy who had completed his education at Norfolk Island would find it comparatively easy to make his way; but here, some reliable elderly man is wanted, to whom the teachers would look up and the people obey.

The school at Fee was in a cheerless state. No effort has been made to complete the school-house, and at the end of the year a worse state of things existed. The teacher had been very ill, and his friends insisted that his own people had charmed him. At this they were indignant, and protested against his return, asserting that it was he himself who had made the charge. At Masevunu the teacher had fallen, and an impromptu arrangement to carry on the school, though exceedingly unsatisfactory, had to be made.

My short stay at Nepek was disappointing in many ways. Last year, Walter Gala, who had lost the confidence of his own people, volunteered to go. We spent the night at Tarasag, the headquarters [20/21] of the district on the way to Nepek. The teachers here, instead of giving him encouragement on his new start, drew a most dreadful picture of the bad nature of the people, which filled him with fears and forebodings. On the journey down the coast, he appeared so wretched that I offered to take him back, if he desired it so. The three head men of the place, on my committing him to their protection, gave every assurance of their goodwill towards him. This seemed to re-assure him somewhat, and after saying a short prayer on the beach and giving him our blessing, we came away with much greater assurance for his future work.

A very good start was made, but most unfortunately, the directions given him had not been followed, and on my visit this year things were found in a most chaotic state. Directions had been given him for a simple course of instruction, and no one to be admitted to prayers until they had been sufficiently instructed. I found everyone had been admitted to the enjoyment of this privilege soon after the school was started. The people had come with a rush, and had left equally suddenly. The teacher got down-hearted, even though about twenty kept up their regular attendance. This is very characteristic of the Gaua teachers, and has happened repeatedly, with very disastrous results. People who are admitted to prayers in this way find it very difficult to see what Christian privileges are, not having first been properly taught, and value them very lightly.

One good thing, however, had attended the opening of the school. The fighting propensities of the people are very great among themselves, and the boats of the labour vessels have been continually fired on. The first thing which caught my eye on entering the schoolhouse was a lot of old muskets stacked at the one end, in all stages of rustiness, but nevertheless formidable in their estimation, and sufficiently capable of producing in the possessors an amount of swagger which bows and arrows do not inspire.

We sailed round the Koru side of the island to Lakona, calling in there for a short visit. The head teacher was in a most deplorable condition, quite incapable for work. The school has been kept going by a Motlav man with a fair degree of success. The school at Togla, a bush village, had collapsed through the want of a teacher, and fighting had been rampant. An equal number of men had been killed on both sides, and overtures were then being made to square the quarrel. At the Koru village, a new church has been attempted, but having so little time to give them, and the place being so isolated, it was making very slow progress.

At Lakona one saw a good deal to give encouragement for the future. The head teacher appears to have gained the confidence of the people, they having accepted and sought his interference in their various disputes. This is a very decided advance, as the presence of a renegade teacher in the past had greatly undermined his authority. The confirmation candidates had been very regular in their attendance, and had shown hopeful signs of greater earnestness. It is through them that we hope to break down among the others the strongholds of the Suqe and the Tamate, customs which, as followed here, are disastrous to their Christianity.

[22] At the Telvan school results were most disappointing. A very capable teacher had given himself for the work, and his efforts to improve the state of things were attended with a temporary success, but a reaction soon took place in favour of the former slack way. A salagoro or taboo ground was inaugurated, and the teacher was left with a very few scholars. The protests of the teacher were unheeded, and rather provoked displeasure; a scandal was raised against him, the usual resort of a disaffected people. As the ship drew near he returned to the school on the shore in very low spirits, with a strong determination to transfer his labours to one of the other villages where they were desirous for schools. He went up to Norfolk Island to be married, and has since returned to help again in the Lakona districts.

The Ulrat school has gone back somewhat from its former enthusiasm. The people on the ridge about the school village, and the school people proper, have taken to squabbling. The former asked for a school of their own and met the refusal with pretty good grace, but are not yet one with their neighbours. While staying here we pegged out the dimensions of the new church, and everything appeared harmonious about its being built; but the old trouble broke out again, and I was unable through want of time to effect a reconciliation. Expecting the Southern Cross by a certain date, my ordinary visit was very much hurried. Unfortunately, this turned out unnecessary, as I was penned up in one place daily expecting her return for more than five weeks. Next year this hurried visit will have to be made up by giving both sides of this island the first consideration.

From here we pulled round to the weather side and got the wind for Mota, which was much stronger than we wanted or expected, and gave us a soaking the whole way round. The schoolhouse was yet uncompleted, but the lime for the last concrete wall had been burnt, and a few days' more work was only required to make the much-desired completion. My Merelava boat crew worked away at the seats round the upper part of the building, the one side of which will be assigned to the head men, and the other side to the teachers, when they assemble to discuss any public matter. The concrete walls were a great success; boards well fastened on either side of the wall posts were filled in with a mixture of lime and sand and rubble.

On my visits round the island there appeared to be evidences of some advance towards a better state of things. The new schoolhouse at Navqoe had been completed, and is more conducive towards a devotional state of mind than its predecessor. The Gatava people we found to be the exception to the general improvement; the schoolhouse was in a wretched state, the people very irregular in their attendance, their whole energy having been captivated by the Suqe. It seemed a case for prompt treatment, as they had been heedless to one's remonstrances for some time. The teacher was taken away, also the bell. The latter, I think, made the greatest impression upon them, as, passing through the village, the bearer wickedly gave it an occasional tinkle while I was having my last say to a crowd of men in the clubhouse. At the end of the year they petitioned for a fresh start and made many fair promises, and I suppose by this time they have got back their teacher.

[23] It will be remembered, perhaps, that the authority in civil matters has been delegated to the representatives chosen by the people. It was, and still is, difficult to get them to take the initiative, especially when the matter requires prompt and firm measures. It is gratifying to find that more determination and spirit has been shown lately in such matters. On one of my later visits, I happened to arrive two or three days after what might have been a very serious quarrel. At Tasmate a misdemeanour had been committed, and had already been settled by the head men of the place, when a party of Luwai people came on the scene and championed one of the disputants. The other party was threatened and rushed for his gun, afterwards taking aim at one of the others. The gun missing fire was the signal for a rush, and arrows flew about very freely, the man with the gun having to exercise all his ingenuity in dodging them. A friend of his got a flesh wound in the cheek, but it was not sufficiently serious to cause alarm. A meeting of all the head men was called, and I happened to arrive the day of the meeting. I was requested to attend, but politely declined, saying that it was their business, not mine, and that I had already busied myself too much over such matters, intending, by so doing, to make them independent of white people in the exercise of their functions. The offenders were fined in pigs, part of which processed past as I sat on my verandah on the return of those who had attended.

In 1893, a trader appeared in his vessel with the object of establishing a trade in this group. His assurances being satisfactory I gave him a letter commending him to the goodwill of all the schools. His efforts have been attended with favourable results, and if present arrangements are carried out, it will greatly contribute to the prosperity of the people, in being able to obtain their ever-increasing social wants and will offer splendid opportunities for making some return for what has been done for them. An arrangement his been made by which the copra raised for school purposes will he paid for in English money. In some places lamps have already been bought, and kerosene is regularly supplied. The Mota people have suddenly become ambitious, and have decided to make copra, with which to buy an iron roof for the coming new church; it will cost, most likely, £30 or £40. The Rowa people are equally ambitious, and are going to buy theirs with beche-de-mer.

A most encouraging stay was made at Motalava. The extra time

spent in waiting for the vessel was acceptable in many ways.

The new church had to be completed, and a better organisation

of the schools was needed. On the day after my arrival at Mota,

the work of the interior commenced in earnest The concrete floor

of the sacrarium was a great success, considering the materials

from which we had to work. An unsuccessful attempt at brickmaking

rather disheartened us, but bricks made of concrete were eventually

successful, utilising the bright red clay of the island over

the lagoon for colouring. When mixed with the lime, the clay

retained most of its colour, which gave us our red; the white

we already had, and some charcoal pounded up with the lime gave

us a kind of blue black, and with these three colours we worked

in our designs with considerable success. My Merelava boat's

crew adzed the boards required for many things, including the

two stalls, as we love to call them, on either side of the [23/24]

chancel. The font has a large concrete base, from which a pedestal

is built up to support a large clam shell brought from the Solomons.

It was a most inspiring time when Bishop Wilson consecrated the

church, and confirmed 58 people the same day in the presence

of a crowded

congregation.

The state of the work on the Valuwa side of the island is very discouraging. A salagoro had been inaugurated, and the district had become tabooed for a stated time in utter disregard of prayers and school. Some years ago, the same difficulty occurring, a meeting of all the people was called, and an arrangement made by which that part of the custom interfering with their Christian duties was abrogated. This agreement has been broken, and the teachers were taken away in consequence. During the hurried visit that I made, the promises to reform their customs were renewed, and school commenced again.

While staying at Ra, on my return from Valuwa, a children's flower service was inaugurated. Something more attractive for children than the ordinary school for the whole people on Sunday mornings appeared desirable. Their existence was overshadowed by the presence of their elders, and in some ways overlooked. All the Motlav children, with those of the Ra school, make a very imposing number compared with the other islands, and this again appeared to argue the desirability of giving them special services. The disposition of the flowers was a perplexing question. Hospitals were very much wanted to relieve us of our difficulty; as these could not be raised, we decided that the flowers should be appropriated for the cemetery, the children to decorate the graves in memory of those whom they had loved and known.

Three teachers of the older generation have passed away. Fisher Pantutun died at the beginning of the year. He was at one time a very active and reliable teacher. Harry Silter died just before my visit in July. He died very suddenly, having taken prayers and school the evening before. He appears to have been very communicative as the end drew near. "The gate of heaven is open, and Jesus is standing there calling me to go quickly to Him," were his last words. He had always been very weakly, but was one of the most intelligent of Melanesians, and very reliable as a teacher. Amy, his wife, died about four months after her husband. Thus the Motlav work has experienced a great loss during the past year.

The year, on the whole, has been a most encouraging one, the disappointments experienced appearing insignificant in comparison with the work accomplished. The latter is full of fair promises for the future. The people are providing themselves with buildings worthily representatives of the work which has been wrought among them by the power of God's Spirit, and have shown themselves willing to respond to opportunities to raise money for church purposes, which will, it is hoped, eventually lead on to a system of self-support.

After a quick passage of a fortnight from Norfolk Island I was landed at Lo on April 23rd. The Southern Cross went on her way at once to the north, this voyage being a good deal hurried in order that she might return to Auckland in time for the consecration of our new Bishop. Consequently she did not stay a night with me, and I decided that it was better to wait for her return from the North, and then have a celebration of the Holy Communion, rather than have one when all were excited with the arrival, and full of the bustle of landing one's things. As I am a Deacon only, this district is still dependent for this privilege upon the occasional calls of the Southern Cross with a Priest on board.

To dispose of the unpleasant part of my story first, I will make mention of two cases which I found awaiting me, and one which occurred at the end of my stay in the district. The first of these cases was that of a young man who had taken to himself the wife of another man who had gone away to Queensland. By native custom, the woman, being deserted, becomes practically a widow, and can remarry. But all three were Christians, and there was but one course to follow. The two had lived together since Christmas, but the teachers had not allowed them to come to church. They now expressed their sorrow for what they had done and agreed to separate, and did so at once, the woman going away to Tëgua, while the man stopped at Lo. I kept their exclusion on for some time, till satisfied by their conduct that they were both sincere; they were then re-admitted. The second case was that of one of the first Christians, who had lapsed into the old heathen customs. I had some talk with him, and he promised amendment. But, during my absence at Tëgua later on, he returned to his old ways, and I had no further opportunity of speaking to him, till I heard he was ill. I went to him at once. He had that morning found a difficulty in eating; by evening his jaw was fast locked; he was conscious, but in much pain; he expressed sorrow for his conduct. At midnight the convulsions, accompanying tetanus, began, and he died at noon on the following day, in terrible suffering and fully conscious of it up till the moment of his death. His end, sudden and awful as it was, made a deep impression on the people, who said that it was the punishment for his backsliding. To myself it was a very painful experience, though quite unable to relieve him I did not like to go away, each struggle seeming as if it must be the end, and every now and then he seemed to beseech one with a pitiable look to help him, till near the last his one moan was "Let me die, let me die."

The last case was that of one of the boys, who was down for his holiday from Norfolk Island. His conduct there and here had hitherto been without reproach in any way. He was suddenly tempted and yielded, and immediately afterwards came to me and confessed his sin, and showed the deepest sorrow and contrition for it. This occurred just a week before the return of the ship from the North on the last voyage, with the Bishop on board. I was able therefore to put the matter before him at once, and he very kindly took the previously unblemished character of the boy into consideration, and postponed [25/26] his return to Norfolk Island for a time only. We took him away from Lo, placed him with the Rev. Wm. Vaget, on Merelava, to be under care for six months. If the report of him is good, he will be allowed to come back to Norfolk Island next year. The whole affair was a very great grief to me, as I was very fond of the boy, and he was the most hopeful one from here now in training at Norfolk Island.

In regard to the first of these cases, I may say that all these matters are rendered year by year more difficult. Owing to the drain which has been kept up from these islands to the labour fields in Queensland and Fiji, the population has enormously decreased, and especially in females. This one fact will speak volumes for itself. I have been able to ascertain that about 20 years ago the population of one of these islands, and that the smallest was upwards of 900; it is now barely 230. Of this number, the youth are almost entirely wanting, old people and little children remaining. There are some seven or eight young men left, and absolutely no women with whom they can mate. This year the chiefs of this Island and of Tëgua have sent the following petition through the Bishop to the Governments of Queensland and Fiji:--

SIRS--We, the Chiefs of the Islands which you call the Torres Islands, ask of you that you will not take away any more people from these, our islands, to work in your country.

There are hardly any but old people and little children left here now; the youth are almost all gone from us. We shall die, for none will be left to raise food for us.

And we ask you not to allow the people of Noumea to take away any of our people.

Such is their pathetic appeal against extinction. I do trust the Bishop may be able to induce those in authority to exempt this group for further deportation. Only this last year, a ship under French colours (the Lady St. Aubyn) called at the Southern Island and took away three unmarried women, with no men of their own island at all. Of course they are very unlikely ever to return, as they will be taken to wife by men of other islands at the labour stations. I must now leave this painful subject, though I burn to say much more, but I trust I have said enough to raise the sympathy of some readers.

With the exception of the cases to which I have referred, I was most thankful to find how well things had been going on. William and his wife Nesta have worked hard with their school at Vipaka, and the children seemed to be doing fairly well, considering the lack of teachers. The school village looked tidy and well kept, and the church specially so. I took down with me many beautiful gifts for the latter from England, including a very first rate harmonium, which has so far stood the test of climate well. William has not much time to preach, but he manages to do all that is necessary, and we made some progress in the musical part of our services in consequence. The interior required some alteration, which had been partly carried out; but we were fully occupied for the week preceding the festival of the Ascension in removing the low cross beams, and placing instead tall side posts and shorter beams at a much greater height; also in arranging and fixing a handsome dorsal and wings which were one of the gifts from England. The question is how long such hangings will stand the climate: but by hanging the curtains quite away from the walls, I am in hopes that these will last quite well.

[27] At Taratawe, Ernest Tughue and Edwin Woqas, (a temporary helper kindly lent me from Gaua on Santa Maria, and who has since volunteered to work here altogether--another instance of the missionary spirit), have kept the people well together--worked hard. When I arrived they had already cleared a new piece of ground for the Mission Station here, and built a lovely little new church. Here the week-day services for the mountain folk are held; on Sundays they all join together at Vipaka. A school was also in building, and when all is quite finished the old site will be enclosed for a cemetery, and the mission village will remove to the new one. Our unfriendly neighbours at the two mountain villages of Rinto and Viriu were still holding aloof, but there were hopeful signs that they might be won over before long.