|

TO-DAY CHRISTIANS Chaplain, U.S.N.R.  |

|

TO-DAY CHRISTIANS Chaplain, U.S.N.R.  |

Patteson is a name held in reverence by the Church of England natives of the Solomon Islands. Like a St. Paul of the Islands he brought the chalice of Christ's love to men whose spiritual thirst had been quenched only by fear and restless spirits. His work and life were ended when, one day as he landed upon some palm fringed coral beach of his beloved tropic isles, he was surrounded and cut down by savage headhunters.

That was not so many years ago. The natives' savage strain, the pagan way of life, is still reflected in the pierced ear lobes, the lime-dyed hair, the tattooed face and breast. So, too, has the spirit of Bishop Patteson lived on--in the work of those who followed him, in the Christian spirit of to-day's native, whose hand lifts the broken body of some aviator, carries him to safety, satisfies his hunger, and places in his fingers that New Testament which symbolizes that in Christ they are as one.

There is a new spirit growing in the islands, the spirit of Christ.

Let us localize the work going on in those islands of the Solomons group. On the shore, near the northern tip of Guadalcanal, framed by stately palm and jungle undergrowth, stands a wooden crucifix some eight feet high. This is the sight upon which stood, some 50 years ago, the first Church of England mission on Guadalcanal. A tidal wave in 1939 washed away the village here, but the inhabitants retreated from the shore and rebuilt their village and their church.

If from this spot, you should walk a mile or two along the coral shore, and turning inland, brave the steaming heat radiating from the jungle floor, the naked rays [2/3] of sun biting their way through palm fronds' meager protection above, you would come suddenly upon a winding tree-shaded river, its cool depth in sharp contrast to the heat through which you have passed.

Site of the School Chapel, completely destroyed by enemy action. On the opposite bank rising sharply, a grass-crowned hill pushes its way above the matted jungle foliage. And on the crest, native huts are silhouetted against the cloudless sky. This is the site of St. Mary's Mission school, Maravovo, Guadalcanal.

You would note, after laboriously climbing the hill, that this mission school is in the process of being rebuilt. All that remains of its earlier life is a cement platform, the foundation of a sanctuary for the original church.

Two years ago, Japanese invaders seized the mission, drove the natives and their missionaries deep into the bush, [3/4] and set up on that site their command post for further operations against the invading American Marines. As the Americans advanced, the mission became a battleground, and when at last a Marine sentry's presence symbolized the victorious end of conflict there, all that remained of Mr. Rowley's labors was the cement foundation of the sanctuary around which his proud church had once been built.

Mr. Rowley, the Church of England missionary, had lived through precarious days. When evicted by the Japs, he gathered together his youthful flock of boys, led them out in the bush, taught them, and took care of their ills as best he could. He and his older boys gathered information of Jap movements which they related to Allied headquarters. They acted as guides. They rescued fliers whose planes had crashed in the jungle. Finally, when food supplies were exhausted, it became necessary for Mr. Rowley to plan a journey across the mountains and swamps of the interior, through the heavily fortified Japanese lines, to reach American held positions where food for his hungry boys might be obtained.

Taking three or four of his oldest, strongest boys, he started out. The trip was hazardous. Scaling the steep mountain cliffs drained their strength. The blinding sun sucked the salt from their bodies. Dizzy and faint, they hacked their way through tightly woven underbrush, waded waist deep in putrid jungle swamps. In one of the swollen streams, habitat of the crocodile, Mr. Rowley lost his foot-[4/5]ing and plunged into the swift current, and was finally rescued, half drowned, by one of his loyal native companions. Often, rounding some bend in a trail, they were surprised by Jap outposts, fired upon, and forced to hide in the jungle maze.

At last, starved and exhausted, they sighted across a field what looked to be an American camp. Weak and tired, they threw caution to the wind and plunged ahead.

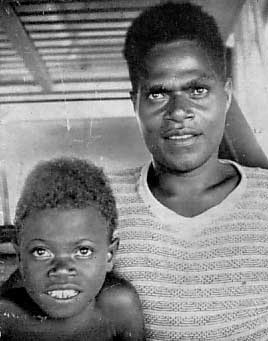

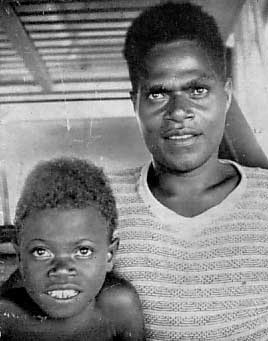

Melanesian School Boys. It was an American camp. They were fed, clothed and given a place to sleep. The treatment given them by the American garrison was all that could be desired, but when Mr. Rowley requested permission to return immediately with provisions for his boys, the commanding officer looked upon his wasted figure and shook his head. Gladly would he furnish supplies, but Mr. Rowley in his present condition could never stand the fatiguing journey back. And it was a miracle that he had been able to avoid Japanese [5/6] capture, so well guarded and heavily fortified were the lines through which he had come.

So it was not until after the mission had become a battleground, and the Marines had rid the compound of its Japanese occupants, that Mr. Rowley again set foot upon his mission compound. A thriving mission school had been engulfed in battle. And that which remained was a naked slab of concrete.

REBUILDING. With the spirit of a man dedicated to his God and pledged to his native congregation, he began his work anew. Huts sprang up made of native log supports, with roofs and walls of interwoven grass and palm. One was a chapel, two were sleeping quarters for the boys, another was a school room, a chapel, a hospital, a dining hall, living quarters for the native teacher and for Mr. Rowley himself. From the ruins, a few usable things were salvaged. Water tanks were patched and re-erected. Driftwood from the beaches provided lumber for an altar in the chapel and desks in the schoolroom. Gardens were grown. A few school books, a small supply of medicines, altar equipment--all hurriedly hidden in the brush with the Japs arrived--were brought forth to restock the mission school. At last the school was ready to continue its work.

Headmaster's House, completely destroyed. [7] It was at this time that Mr. Rowley, who is a deacon, heard of my presence nearby, and asked me if I would celebrate the Holy Communion for the boys. So it was that I travelled to Maravovo aboard the mission vessel Patteson, trekked through the jungle and up the hill to the mission chapel. It was shortly before Christmas when I was there, and as each boy received the spiritual presence of Christ, I could not help but recall the words of the Angel when the child Jesus first came to earth, "I bring you good tidings of joy which shall be to all people." And so, out here in the steaming jungle, dark-skinned native boys knew that same joy which comes to all people as they open their hearts to the presence of Christ.

SCHOOL LIFE. Let us look into the inner life of the school. The students are selected by the Bishop of Melanesia, from among the most promising-looking youngsters in the islands. They come here from islands within a radius of 500 miles. Normally, almost 200 boys are enrolled. The war has temporarily limited the number to 45. The school course lasts three years.

The School "bus" If you should wander about the compound observing the daily routine, you would find that the boys arise at 5:45 a.m. It takes little time for them to dress, for that operation consists only in wrapping a piece of cloth about their waists. At 6:15 they enter the chapel for morning prayers, or, when a native priest is visiting the school, a celebration of Holy Communion is held. The breakfast which follows is composed of native fruits, and occasionally a duck's egg. Then comes a period during which the boys do the chores, cutting the grass with strips of bamboo stick, raking the dirt floor of the school room, cleaning their dormitories, rebuilding the ruined chapel. (The present chapel is but a temporary one.) The remaining three hours of the morning are reserved for classes. Sitting in their bamboo classrooms at small desks made of driftwood, the boys study English, arithmetic, penmanship, Bible, and catechism.

After the noon meal of biscuits, tea, and fruits, they work in their gardens. Out in the bush, each boy has his own garden, where he grows sweet potatoes, corn, [7/8] cabbage, bananas, pineapples, and a native vegetable, purple in color, and somewhat resembling the cabbage in size but with a turnip-like texture.

The boys play ball, swim, and race about during their recreation period, but promptly at 5:15 p.m. they gather again in their chapel where the native teacher, Nelson Gao, leads them in Evening Prayer.

Then the boys disappear into the bush, gathering in small groups at their gardens. They prepare their own evening meal. Usually they make a stew. Into a pot or kettle, they drop coconut meat, sweet potatoes, cabbage, pineapple, bananas, a piece of wild pig, or perhaps a fish they speared during the day. This, well stirred and heated over an open fire, is the native version of a well-planned dinner. The meal ended, they return to their classroom for a final course in geography and hygiene. Then comes bed. There is the usual noise and joking as they enter their dormitories and climb into their beds, which are bamboo-framed and lined with woven grass matting, the whole being suspended above the ground on wooden poles. And so the day ends.

So, to-day, because there is that missionary, that school, those boys, you may see in some remote village, a group of natives gathered about their evening camp fire, welcoming the return of their son, and learning from him that there is a Spirit greater than the spirits of the jungle, a love which banishes fear. It is the Spirit and the love of Christ.

____________________________

LANGLEA PRINTERY PTY, LTD.

433 KENT ST., SYDNEY.

Project Canterbury