|

CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE |

This little book is the result of a brave attempt to keep a stiff upper lip in the first disappointment of giving up mission work. Retiring missionaries know that the real sacrifice of houses and lands and children comes at the end, not the beginning, for there is then a hundred times as much to leave; and most of us try to make the leaving easy by persuading others to carry on our work. That is why these sketches came to be written. And I suppose it is because I know and love "our land," and because I visited the writer during the weary months of sickness, that I have been asked to write this note.

"Our island" is one of many in the Pacific where the Melanesian Mission is doing its splendid work. It is one of the smaller islands, with a population of 6,000. The majority are Christians, and live in little villages of bamboo and palm-thatch, usually near the shore; the remaining heathen are found in scattered hamlets dotted about the bush. The name [iii/iv] RAGA does not really matter, for the people are much the same everywhere--a charming, simple folk, full of contradictions and surprises, trying to puzzle their way through the difficulties of the new teaching and to adapt themselves to the strangeness of white civilization. Other books will tell more about the actual work of the Mission: "The Light of Melanesia," "The Islands of Enchantment," "The Isles that Wait." This is just an appeal for sympathy and understanding of the people themselves. All I really want to say is that the stories "ring true," and that these people desire and deserve the best we Christians have to give.

H. N. DRUMMOND.

|

PAGE |

|

| FOREWORD |

iii |

| HOME |

7 |

| CHRISTMAS |

13 |

| PEACE STONES |

20 |

| MAN |

25 |

| COMING TO SCHOOL |

31 |

| WIDOWED |

36 |

| THEY THAT GO DOWN INTO THE SEA IN SHIPS |

41 |

| PESTS |

48 |

| WHAT'S IN A NAME? |

57 |

| THE RED DRESS |

63 |

| HURRICANES |

70 |

| BABY MAY |

78 |

| AFOOT AND AFLOAT |

84 |

| TINS |

92 |

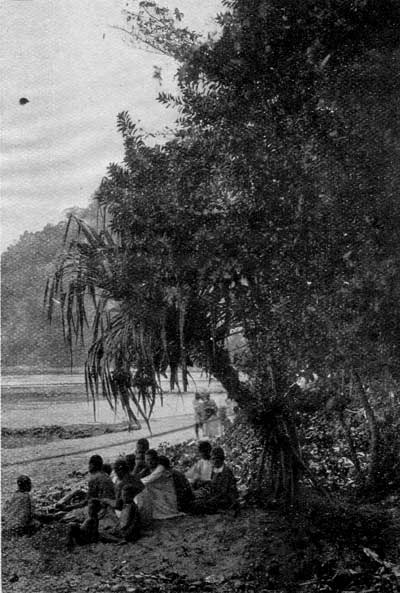

SINGABEL'S VILLAGE (ON THE POINT) Frontispiece

FACING PAGE

A MAN OF RAGA, NEW HEBRIDES 32

RAGA WOMAN AND CHILD, NEW HEBRIDES 48

ON THE ROAD TO ATABUL 64

"ARE you glad to be back?" someone asked the Gentle Lady as we leaned over the rail watching the approaching coast-line of Raga.

"It is my home," she answered.

I heard. Should I ever feel like that? I looked at the deep curve of the bay, with its quaint mushroom-like rocks on the right and the precipitous bluff on the left, the beach of fine white coral, and the dense bush running back into the hills. It was very hot. We went down the gangway to the whaleboat that was to take us ashore. As we were rowed in my attention was called to a patch of grass on the hillside.

"When you get there you find that grass is twelve or sixteen feet high."

It added to the strangeness to be told that!

The boat grounded on the sand, brown hands supported me for the jump from the bows to the beach, and I had arrived at my destination.

The Gentle Lady was warmly greeted by [7/8] men, women and children; she chatted to them in their own language, smiling and inspiring smiles. We moved off along the path that led to the Mission-house. One walks in single file always; the paths are narrow, and it is the custom of the country. So, walking thus, we plunged into the shade beneath the coconut-palms, some of which, by their drunken angles, bore testimony to the direction of the hurricane that had swept the island eighteen months before.

We crossed a kind of bridge built of coral blocks and compacted with earth, to span a depression that evidently became a swamp sometimes. On the other side we came to a steep rise, at the top of which stood the little iron-roofed Mission-house, and the grass that bordered the path up there was starred by the fragrant blossoms of the frangipani. It was an unexpected gift of beauty, a lavish glory, and a memory that still burns vividly within me. I think that the scent of the frangipani blossoms will always sweep me back to that path, and to my first night in the islands.

There were two house-girls smiling a greeting when we entered the house. I was to learn later that one of them was the heroine of a sorry romance, the victim of the eternal triangle; [8/9] but that night to me she was just a plump, smiling, native girl. With nightfall we said good-bye to our friends; the ship sounded her siren three times in farewell, and slipped out of the bay on her way north. We were two white women alone.

Our position was a commonplace to the Gentle Lady, but to me it was an adventure. The evening was still and starry. Every scent and sound was strange; the heat was enervating; everything seemed unreal; and, indeed, for months I used to think that it must all be a dream--that I could not really be doing all these unusual things in such strange surroundings. The queer food out of tins, and the native vegetables and fruits; the constant fight with innumerable pests; the quiet of the nights, broken only by the shrieks of night creatures; the blazing sun; the sudden coming of dark and dawn--all these things combined to make me feel that I had dropped down into another world, where prejudices must be discarded, the ideas and ideals and training of one's previous life must be moulded and adapted if they were to be of any use.

But that first night I was intensely conscious only of the bush, that rose to a great height a few yards from the house on one side and [9/10] dipped into a gully, thence to climb the hills on the other side. There is personality in bush. This was oppressive, menacing, almost sinister. It was shrouded by a creeper, which spread greedy arms to anything that would give it hold, and flung great curtains about the loftiest trees. A more amazing vital thing I have never seen. Flaunting and gay, it grew and grew, despising no ground, needing no support, smothering and strangling as it spread. I have seen its wanton shoots reaching out across the sand, and have felt glad when the tide came up and killed them.

Though the presence of the bush oppressed me, I slept well that first night; and next day I was so busy finding my way about this new world, and using my scanty stock of Raga words upon mystified natives, whose intuition (confirmed by my gestures) had to supply the deficiencies in my vocabulary, that it was nightfall again before I realized it. This I found was one of the delightful features of the life; the days flashed past. They never dragged; weeks fled, months went by, and still that feeling of adventuring in a strange land persisted, and I never lost it.

I learned to know that bay and the little village, of which we were a part, in all its [10/11] moods. Out of the first jumble of impressions definite facts assumed form. Where I had seen just a plump, smiling house-girl, I now saw a passionate woman, the wife of an old man, the beloved of a young one, and the victim of her parents' greed. Where I had seen just a roughly-made bridge, I saw a place rendered dangerous at all times by large crab-holes, and in wet weather with a surface like greasy glass, across which one was apt to do involuntary jazz steps unless very careful. I learned to know it also a spot of great beauty, full of ferns and brilliant cannas and gay convolvulus, very shady and very still. The "Ferned Grot" the Gentle Lady named it. We had a garden, and loved to quote those lines beginning:

"A garden is a lovesome thing." Where I had seen wretched thatched huts and indecent scantiness of clothing, I now saw dwellings suited to these hurricane-swept islands and a people hygienically dressed for this climate. Where I had seen just a group of weedy-looking natives, I saw men and women with emotions like those of their white brothers and sisters, who laugh and frown, praise and blame, love and hate, through the days. They, [11/12] too, are busy getting and spending. They, too, have their ambitions for possessions or power. They, too, have social rank. There is scandal, there is joy, there is sorrow, there is love--the age-old human whirligig wherein one is born, grows up, marries, has children, does just so little or so much, grows tired, and dies.

What is it for? We see life stripped of the complex trappings of civilization and behold the stark reality. In civilization you are caught up into the whirl, and are so busy doing things that you do not see the futility of most of them. Here it is different. You stand aside. You do not know the language yet. You watch, and think, and puzzle. They are very busy. Is it worth while? And what is it all for? You cannot live long among a primitive people before that problem faces you. You can only reply to it in terms of your own faith.

THERE has always been something very attractive for me in pictures of the conventional English "snowy Christmas," and I have always cherished a hope that some day I may experience it, and meet those jolly people whom I know so well by sight--the warmly-clad folk, plump and happy, who wish one another a "Merry Christmas" as they trudge through the snow to church, and afterwards gather cheerily round the festal board to eat roast turkey, plum-pudding, and mince-pie, and then play merry games in rooms made cheerful with wreaths of holly and blazing log-fires. My Christmases have always been in summer-time, when the proper Christmas doings are a weariness to the flesh, or their absence an exasperation to the soul. But when I found myself in Melanesia I felt as eager to experience an island Christmas as I had been (and still am) to know a snowy one.

In the isles the festival comes in the hottest part of the year, and that first hot season was intensely hot, and accompanied by almost ceaseless rain. During a period of over six months [13/14] we did not have more than two consecutive fine days, the rain varying from a torrential downpour to a fine drizzle. Throughout the season one's clothes seemed always damp, a musty smell clung about cupboards and trunks, and mildew flourished everywhere. The sun was hidden for weeks at a time, till I began to ache for a sight of it, and the overcast sky kept us in an atmosphere that can best be compared to a steam-bath. All round us the brooding bush was stimulated to a savage growth.

Christmas approached. By great good fortune the eve was fine. That was a matter for rejoicing, as it was necessary for us to spend the night in a village some distance away in order to be present at the Eucharist on Christmas morning. There was only one priest, so a central spot had been chosen at which the communicants of the district would gather for the service.

When you make a journey of that kind on Raga you must take with you everything that you are likely to need--bed and bedding, mosquito-net, chair, change of clothes, food, and even water. The disabilities of the white man in the islands are forced home on such expeditions, for his brown bother needs only a small bag on his back in which to carry [14/15] everything necessary for his health and comfort, whereas the white man needs several porters to carry what is the bare minimum necessary to guard his health. We set off, the Gentle Lady and I, followed by a train of natives carrying our gear.

Very beautiful were the paths we traversed on our way to the prettily-situated village of Atabul. It clings to the side of a hill, and views the ocean through a veil of trees, which shelter its clustering houses and throw a welcome shade across the grassy compound that separates the church and school-house. Grass is uncommon in such places, and the Gentle Lady answered my surprise with the explanation. Years before she and her colleague had had a house at Atabul, where they would spend a month at a time, and she had planted the grass. This had kindly spread, so that now it made an ample carpet for the happy groups of natives seated about. Festivity was in the air. Laughter rang out, and chatter was everywhere.

We were lodged in the school-house, which was the usual leaf-thatched hut with an earthen floor, and contained a native bed--a sloping bamboo platform, standing about eighteen inches from the ground.

The first thing to be done on one of these [15/16] expeditions is always to fix up one's sleeping-place and mosquito-net. Owning no traveling "stretcher," I was to use the native bed, and now I eyed my couch with a dawning suspicion of its hardness, that was but the faintest suggestion of the discomfort to be realized. We were interrupted by a constant stream of visitors, so we hung a curtain across the door-space--there being no door--and when we were ready swung it back again.

Crowds came to pay their respects to the Gentle Lady whom they had known so long, and whom they had not seen for a couple of years. It is a very vivid memory: my companion seated on a deck-chair in the school-house, and the callers coming and going, squatting on the ground and chatting awhile, and then giving place to others.

At evensong the church was packed with a devout throng of people. The Reverend Matthias Tarileo, the native priest, took the service. We two were the only white folk then in North Raga; and, indeed, it was during that spell that we saw no other white face for six months. The crowd made the building very hot, and our discomfort was not mitigated by the seats, which were rough-hewn logs placed on two uprights to make forms.

[17] The church was decorated for the morrow, and the altar looked exquisitely beautiful with its lights, and vases of pale pink wild ginger mingled with leaves of a fine yellow croton. There was unusual artistry in the colour scheme and in the arrangement of the flowers. I have never seen pink ginger-lilies since, so they seem to belong specially to that festal evensong at Atabul.

We came out of the hot church into the night. If you know the glory of coming upon some great and unexpected beauty you will understand how I felt on stepping out into a moon-washed world, mysterious with shadows, fragrant with the scent of orange-blossom, and musical with human voices. Christmas Eve in a village high up on the hillside of a tiny island in the Pacific! Yet I have heard it said that romance has gone out of the life of the missionary in the isles, and that only the drudgery remains.

We retired early. My bed was harder than I had imagined possible. I tried every conceivable position, but the iron hardness of that bed penetrated. At last I dozed, to be awakened by rain pouring down outside, and the Gentle Lady examining the leaks at my end of the bed to see whether I was getting wet. It was midnight. We resumed our efforts to sleep.

[18] After the restless night we rose early, for the service was to begin at six o'clock. When we entered the church there were numbers of men and women already kneeling there, and gradually the church filled till it could not hold another person. Everyone present was clad in a best garment, whether a cherished suit or a native malo (loin-cloth), that was clean and whole, to be worthy of the Christmas festival. The quiet devotion and reverence of the Melanesian are wonderful.

The service was very long in the hot little church, but, nevertheless, it was very beautiful. After it was over the church refilled with the communicants who had been waiting outside, and the service was repeated.

Breakfast followed--poached eggs on biscuits--and immediately afterwards we packed up and returned home.

With nightfall weariness overtook me, and I went to bed early, hoping to make up my previous night's lost sleep, though warned that there might be interruptions.

Suddenly I was awakened by lusty male voices, which seemed to burst right into my room. Carol-singing is a custom upheld with much zest in Melanesia. The singing was deplorably flat, but commendably hearty. Pres-[18/19]ently it ended, and I closed my eyes. Just as I was dozing off I started awake again, to find a hurricane-lamp being set down on the veranda. A murmuring of voices, a general clearing of throats, and once more from powerful lungs rang out the well-known carols. Two or three were sung, and then they left us. All night long this carol-singing seemed to go on. By the time the third batch had begun the careful coughing, which was a kind of preliminary clearing for action, I was feeling quite hysterically mirthful. Of course, I was utterly ashamed; but they were so solemn about it, and they always got so flat, that I could not help it. The Gentle Lady courteously expressed our thanks. When they had gone my laughter had its way; but a fresh lot of carollers was coming up the path, so I took stern hold of myself that I might receive the next company in decorous silence. The whole island seemed to be on the move in an orgy of carol-singing.

Now, when I look back, I find that my memory of the carols of Raga is wrapped in tender thoughts of the deep earnestness and joy of those brown-skinned Christmas singers, and enshrined in gratitude for a memory so precious as that of my first island Christmas.

IT was upon a Christmas Eve--appropriately enough--that I first saw the Peace Stones of Raga. In Christian Raga there is a custom at this season of clearing the paths that lead about the country. They are mostly old highways, and consequently wide; but in spite of frequent clearing the grass grows so quickly that most of the year they are overgrown except for a narrow track down the middle, which is constantly trodden by the natives walking in single file. I had come from Central Raga, with its sketchy and difficult bush-tracks, and was not prepared of the beauty of the North Raga paths. To walk along them was like walking in some splendid garden, so astonishing was the variety of graceful palms, shrubs, and ferns growing in the shade of imposing trees. Crotons made splashed of colour, and the tall red spikes of wild ginger lifted their stately heads; orchids and flowering creepers clung to the trees; and an artist among the natives had built in an open space a pergola, over which a granadilla vine draped its glorious purple blossoms and pale green fruit.

[21] At the crossing of two paths one almost always found a large banyan-tree, and sometimes, at the foot of it, stones for making the native oven. Whether the natives, using the banyan as a landmark, gradually wore a track towards it, or whether the banyan was planted at the cross-roads, I do not know, but its shade spread across the open space made by the intersection of the ways and made a welcome resting-place. I have met the children of the village of Agatoa sitting in the shade of the banyan near their home playing a game in which their fingers traced patterns on the ground. Quite a suitable pastime I thought, for the place and temperature.

Walking along the paths one passes old gardens with low walls of piled white coral stones, over which spreads a purple and silver creeping plant, the variegated tradescantia of European greenhouses. There are groves of pawpaw and bananas, and innumerable native fruits and nuts, and a very common object is the famous breadfruit-tree. Here and there is the cleared expanse of a yam-garden, where the men and women labour with zeal to produce a good crop of that great tuber that forms their staple food.

In Raga the yam-vine is trained up a thin [21/22] bamboo, which is then bent over to form an arch; when the bamboos are covered a yam-garden is a very pretty sight, with its hundreds of vine-laden arches. It has never ceased to astonish me that so small a vine can produce such enormous tubers. Tropical nature is very amazing, and always filled me with awe. Little wonder that the native mind peoples the natural world with spirits, evil and malign! Little wonder that they try to propitiate them!

The yam-gardens are exposed to the full blaze of the sun, and one is glad to plunge back into the bush, where there is shade and the fragrance of blossoms. Everywhere is heard the throb of cicadas; day and night they seem never to cease. Unless you have seen the lavish growth, the glory and the beauty of the bush, you can have no idea of its charm. Every glimpse is a picture, and every turning presents a fresh loveliness.

In my first walk along those paths two memories stand out very clearly. The first is of a young man, brown and muscular, in native costume, with a knife tucked in his belt, striding down the path; he was lithe of step and alert, a Melanesian Apollo. He approached us, smiled, and halted. Only then did I recognize in this splendid young native a well-educated student, [22/23] whom hitherto I had always seen disfigured by European clothing.

"Why do they commit thee offences against good taste?" I groaned. "If only they would realize the artistry of their native dress! It is so suited to their environment. But to put on trousers!"

"Yes," sighed the Gentle Lady, "that is bad enough; but to extinguish completely their natural charm it takes a hat!"

My other memory of that walk is of the Peace Stones. At a turn of the path we came upon the first pair, and at first I thought that they were graves. They are made of pieces of rough white coral piled into symmetrical rectangles about five feet long, two or three feet high, and three or so in width. There is just room for a man to walk between them. They are kept in good repair, and seem remote and still in the midst of the rapidly growing bush. In the shade, on the path, a few yards from each village, you will find them, these Vatu Tamata, or Peace Stones. There is something about them, the poetry of their name, the passing of their use, the stillness of their white beauty among the green and the shadows, or it may be just that suggestion of graves--whatever it is, a wistful quality clings about [23/24] them, the pathos of usefulness that is past. For they are not needed now, when men no longer carry arms.

In the old days, not so long ago, a man would not leave his village without spear, club, or arrows. These people did not meet one another in open battle, but attacked from ambush, taking life, though they knew that at some time life would be taken in revenge. In those unhappy days a visitor must lay down his arms upon the Peace Stones before entering a village in token that his visit was a peaceful one. Times have changed. No poisoned arrows now rest upon those silent stones. Women and children go unattended along the ways and men unarmed; but the Peace Stones remain, a silent witness of days when Terror lurked in every bush and Fear trod sharp upon the traveller's heels.

WHETHER he acknowledges it or not, man still believes himself much more important than woman. Whether woman shares this opinion or not is another matter. In the islands it is an accepted fact; both man and woman believe with all their hearts that man is not only the more important, but the incomparably superior. It is no use bothering about it; there it is. You may emancipate woman in any way you like; you may convince her husband that she does rank higher than his valued pigs; you may even persuade him that it is a mistake to thrash her; you may show him that she can learn to read and write as well as he, perhaps better; but you never will convince him that she is his equal.

The men take their superiority very seriously, and there is something humorous to us in the way they lecture their women-folk. A girl comes to school, and very soon her uncle or other important male relative, or (if she is betrothed) her future husband, will arrive and ask permission to speak to her. Very demurely the maiden appears, her whole demeanour one [25/26] of respect, amounting almost to awe, for this august person. Every other girl in the school is pricked to interest about the interview. The maiden seats herself at a respectful distance with eyes averted, and the lecture--for such it is--begins. Usually she is urged, perhaps commanded to, "mind her teachers, kind and dear"; to be diligent and truthful; not to gossip nor quarrel. Meekly she listens, meekly retires when the address is finished, and in a few minutes is mercifully relieved of the oppression that had settled on her soul and is an ordinary girl again among girls.

One rather fine boy--albeit, something of a fop--wished his fiancée to enter our boarding school but his mother-in-law-to-be was obdurate in her refusal to allow it. When, however, the dainty Metahalib was fully paid for, and therefore his to control, he sent her to us. Thereupon some trouble arose, the mother-in-law having a sharp tongue. So the boy, who was very fond of his little fiancée, came up to the school and talked to her, telling her that she must not listen to her mother's persuasions and the gossip of the village, but must stay at school, learn what she could, work hard, obey, and, in fact, be a model of all the maidenly virtues. The two were unusually easy and [26/27] natural together, and Metahalib must have been a girl of strong nerve, for her voice was heard taking part in the conversation at one time instead of remaining mute. In the presence of men young women in Melanesia usually become dumb and as unobtrusive as possible if they are nicely-behaved young ladies according to their code. They step off the path and stand aside if a man is approaching, continuing on their way only when he has passed by.

We were clearing the path that leads to the school one day. It was sunshiny after rain, and the bevy of schoolgirls, laughing and chattering as their knives slashed rapidly, made the bush ring with merriment. They were alive with joy as they worked. Suddenly came a hush. I looked up. Every girl had stepped off the path, and was standing with still hands and downcast eyes. It was as if the sun had blazed down upon a bed of sheltered lilies and had set them drooping. I looked for the cause of this phenomenon.

Down the path came three youths. Looking neither to the right nor left, but straight ahead, they passed like kings. This deference was the due of these royal beings who were men. Was it not right that their inferiors should express humility in their presence? So they [27/28] passed, and only when they had disappeared into the bush was work resumed and laughter renewed.

Occasionally there crops up a dynamic creature of the female sex who dominates and controls her men-folk, but she is rare. I know an old lady in a hill village whose husband, being an invalid, has laid upon her the burden of his work, and with it something of the sternness of his sex, so that, for a woman, she is unusually direct and purposeful of manner. And there is in North Raga a family of four generations whose women are more forceful than most of their sex in Raga. The elderly great-grandmother is still vivacious in spite of her years; and her handsome daughter, wife of a powerful chief, is a strong character and a notable personality in any gathering. It was at Atabul that I first met them, whither I had gone with the Gentle Lady to attend the Christmas celebration. Numbers of people called to see her, and among them the chiefs and their women. The great-grandmother, not instantly recognized by the Gentle Lady, who had not seen her for several years, announced herself with dramatic gesture, and opened up a lively conversation that left her hostess smiling. When the daughter called with her husband, [28/29] the chief, she joined in the conversation with a self-possession equalling her mother's. The grand-daughter was one of our first boarders, and she, too, had personality. When she had been with us for a couple of weeks her father and some relatives who had come down the coast on business of sorts, came to visit her. She received them with delight, and was, you could see, enormously proud of them. Bringing her father into the sitting-room where I was writing, she introduced him to me, explaining to him that I was ignorant as yet, but that I was trying to learn--a perfectly correct statement! This same girl is now the wife of the first native Raga priest, Matthias Talileo, and has a daughter; but she is just a tiny babe, whom I have not seen, and I do not know whether she has yet shown any signs of carrying out the family tradition and becoming a lady of strong character.

At any gathering, even in church, the men sit on one side and the women on the other. The most spectacular dances are for men, and any women's parts are taken by men. The club-house is solely for men, the bargaining in marriages is done by men, the chiefs are men, the laws are made by men--and yet in this man-dominated world you belong to your [29/30] mother's clan, not to your father's. That method of tribal division comes down, I believe, from a more primitive social organization, some of the laws of which have persisted unto this day.

All things considered, however, the men of Raga are not the hard task-masters they may at first appear to be, for if they do let their wives and daughters cut and carry mighty loads of firewood, they in their turn sometimes carry the baby; and if they do make their women work in the gardens, they themselves work there too. You meet them returning from their toil in the evening, the husband going first, carrying very little, if anything, and the wife following her lord with shoulders bent beneath a heavy load, and perhaps in her arms a baby, and you naturally feel indignant, until you learn or remember that once the man went thus carrying arms to protect his lady, and the custom survives; just as our convention persists that a man must take the outside of the footpath Then you temper your judgment, and begin to understand that the foundation of most of their customs is not sheer savagery, but some fundamental social necessity.

OUR work in Raga was among the women and children, and the villages were divided into groups that came on stated days, so that every village had its turn once each week. It was not a perfect educational scheme, but the best that two women could manage in the circumstances.

As there are no clocks in Melanesia, a bright day finds the scholars gathering before breakfast about your doors, whilst a dull one may find them arriving towards noon, so that a certain elasticity of time and temperament is necessary to success there. No Melanesian is worried if a long wait is necessary, and contented groups of women sit chattering under the trees, while near them stay the little girls. The boys, being boys, find other amusement.

For a short time before the bell is rung to call the people to school, a certain amount of bartering is done: the fruit, vegetables, and eggs needed for our larder, are exchanged for fish-hooks or some small thing of that kind. Now also those come to us who wish to buy any of the books printed in the Mission, and the sick, or their friends, apply for medicine. A [31/32] sharp lookout is kept for the various contagious skin diseases which, though easily checked in the early stages, spread rapidly and widely if neglected. When all this business is finished the bell is rung, and the whole congregated mass of natives assemble for singing.

Photo, Beattie, Hobart A MAN OF RAGA, NEW HEBRIDES There are old, old ladies who are grandmothers, young women, girls, boys, and mere babes. But to none of them is there anything incongruous in the mixture. We begin by singing, or we try to. When voice-exercises were first introduced, the dear old ladies looked as if they thought they were in the presence of a harmless lunatic whom it might be well to humour; but something had to be done to help those poor, croaking throats. As time went on the exercises become a commonplace and they seemed almost to like them. But we'll never be singers on Raga. Few of us can detect semitones, and so we are often excruciatingly flat. We struggle for weeks, months even, to sing a tune with a few accidentals in it, and some of us get it; but most of us don't. For months we hammer away at a few hymns till we think we know them; then one day the teacher finds herself in a village church, and one of those hymns is sung, and she goes away sorrowful. On Raga it is fashionable to begin a hymn on [32/33] the right key, and finish it several tones lower. However, as the August Person remarked, the singing there is certainly hearty.

After the joyous episode of singing, the women and elder girls go to the Gentle Lady, while the boys and little girls remain with me.

Melanesian children are very well-behaved in school. They sit in rows with solemn faces lit by dark, shining eyes, taking the business of education most seriously. On Wednesdays the children of Atabul come to school. Atabul is a pretty little village high up on the mountain side, and long before school-time the bush is ringing with the shouts and laughter of the children as they come trooping down the steep paths to us. Down they come, big and little, boys and girls, the latter in a troop apart or with their mothers. Children from villages nearer the sea sometimes paddle across the bay in their own canoes, handling the frail craft with expert skill and singing as they go, but the children of Atabul live high up above the sea, and there is only the bush path for them.

When the noisy, chattering crowd arrives at the beach, it looks about for amusement to occupy it till school begins. Sometimes the boys plunge into the sea for a swim, or, if the tide is right, take their bows and arrows to shoot [33/34] fish in the enclosure on the reef. If the Mission whaleboat happens to be anchored in the bay, it is very soon surrounded by a merry crowd of boys who swarm in and out of it like brown seals, swimming round it, diving or jumping off it, and good-temperedly struggling for the best place.

When the bell goes, they scramble up the beach, shaking the water out of their eyes like so many wet puppies, and, with their wooly hair and brown bodies glistening wet, go soberly into school. For them there is a great solemnity about the affair, and the noisy crowd of a moment ago becomes subdued and quiet. Each boy takes his seat and waits, wide-eyed and still, for the opening. Should any small youth so far forget the proprieties as to speak or fidget, he is immediately quelled into submission to the unwritten code by frowns and whispered commands. They are very, very good in school, these children of Atabul, and very serious about such portentous matters at the three Rs. Even singing is treated with the gravest respect. They are a dear, lovable crowd, my Atabul youngsters, and yet I never see them gathered for school without a quick clutch of pain at my heart for one of them. He is a cripple bearing the brave name of Daniel, a little fellow with big, brown eyes and a wistful expression, but a [34/35] stout heart, for he will not let his affliction handicap him. His legs are shrunken, but he gets about with the aid of a strong pole. Down those steep and difficult paths he comes with the other boys of his village, somehow managing to keep up with them as he thumps along with his pole. His companions are very kind to him, treating him with tactful instinct as one of themselves, standing aside to give him room to pass, but offending with no officious help. My heart is wrung for Daniel when I see the other lads plunging about in the sea or rushing round in games, while he must sit and watch.

The first face I look for on entering the schoolhouse on Wednesdays is Daniel's. There is something in his eyes--a heritage of suffering--as he looks up and responds to my smile. The brave little brow is beaded with perspiration when the rest of the children are cool, but there is no other sign of the effort his school attendance costs him, and I think likes the benches they sit on, because they hide his legs, and then he is just like the other boys, who can run and climb trees and swim.

Dear little Daniel, crippled in body, but valiant in spirit! How I miss him when the paths are too slippery for even his stout heart, and his place is empty!

QATNAPUI was like a dying village, for the inhabitants were becoming fewer and fewer. Not many years ago it was very populous, because the Kanakas of Raga, when repatriated from Queensland, had settled there. But now from various causes it was growing smaller and smaller. There were a few houses by the beach, a few in the bush near the church, and another little group just below the Mission-house. The dwellers in these last used our path; and sometimes of a night we would see a flare coming up the hill as a party returned from fishing or some other nocturnal business. There is unstudied artistry in everything these people do, and their primitive lamps are strikingly beautiful. They bind a bundle of fine, dry bamboo, about six feet in length, light the top, and proceed, occasionally swinging it to stimulate the flame. A string of such flares passing round the hillside or dotted about the reef on a dark night makes a beautiful sight.

So up and down the path, grass-grown since [36/37] there were few to tread it, passed our neighbours, and among them were Ellen and her husband, Billy. Ellen was the mother of two children--Hagar, a funny little mite of three or four years, who usually wore nothing, but when attending school was dignified and inconvenienced by a dress which was the reverse of clean; and her baby sister, a tiny, unhealthy-looking creature, who was carried on Ellen's back, and enlivened her attendance at school with bouts of wailing.

Thinking that perhaps its natural food was not sufficiently nourishing, we told Ellen that we could give her milk--it was condensed, of course, but that is quite good for babes--and she promised to send for it daily. On several occasions Billy came with the pannikin for his baby daughter's milk. He was young and strong, bright and smiling, and I watched him stepping carefully as he carried his pannikin down the hill till he moved off the path and disappeared among the trees that sheltered their house. One day neither he nor Ellen came for the milk, and at dawn of the day following I was awakened by a great groaning and howling and moaning. It was the death-wail. Word was brought to us that Billy was dead. Such sudden deaths are not uncommon [37/38] on Raga. The wailing continued for hours. Then the body was buried in the cemetery by the sea, and quiet again prevailed.

A few days later, towards sunset, as I was passing down the path, I saw a crowd of women outside the widow's house. An oven had just been opened, and the food apportioned and spread on fresh leaves ready to be eaten in the manner of this feast, which is part of the ceremonial that follows a death. A little apart, beneath the frangipani-tree and among its fallen blossoms, sat the widow with her babies--themselves looking like broken blossoms in their grief.

My heart swelled with pity. For days the memory of Ellen seated beneath the frangipani-tree troubled me. She had looked so utterly forlorn. Bravely she appeared at church, and we gave her smiles that tried to express at once our admiration for her brave bearing and sympathy for her lot. The village had been full of visitors for the burial and subsequent death feasts; but presently the visitors returned to their homes in the hills or down the coast, and Qatnapui settled back into its accustomed tranquility.

A fortnight had not yet passed when news of a wedding that had taken place that morning [38/39] in the village set the whole school a-simmer with gossip. John had been married.

I was interested in this John, as there was a rumour that he had approached the relative of one of our maidens "with a view to matrimony."

"Who is the bride?" I asked.

"Ellen."

If the answer shocked and startled us, it was at least a relief to find that the people themselves thought it somewhat unseemly, for three months is the conventional period that should elapse before remarriage. But it seems that widows cost less to purchase than unmarried girls; and then on Raga there are never enough women to go round. Moreover, there is the strict law that forbids marriage with any but the opposite clan or "side of the house." There are two "sides" of this metaphorical "house," and a child (as has already been said) belongs to its mother's side. It is permissible, therefore, to marry a cousin on one's father's side, but infamous to unite with a cousin on one's mother's side. In consequence of the shortage of women, which is said to be a sign of a dying race, and the barriers of the clan system, there are some very incongruous couples, which inspire the outsider with a desire to sort and rearrange them in more seemly union.

[40] There is dear old blind Billy, who lives alone by the seashore because Polly, his girl-wife, deserted him for a more youthful mate. Poor Polly! We heard that her lot was to be deserted in turn by the man for whom she had left her husband. Hers was an unnatural marriage, probably the outcome of the greed of relatives, for Billy had come back from Queensland a man of wealth, as wealth is counted in the eyes of these simple people.

Billy, nearly blind, gropes his way to church every day; and every Saturday, when the churchyard is swept and tidied for Sunday, he is first with his broom of dried twigs.

Then there is dear old Muriel, a grandmother who is as active of body as she is nimble with her fingers and sharp with her tongue. She is married to a very young man, who was alleged by his spouse to have looked at Polly with admiring eyes, and his wandering attention stimulated her tongue to rebuking the girl-wife with stinging jibes. Gossip flew to and fro, leaving heart-burning and misery; and then a horrified village learned that Polly had fled. Scandal lifted its head, and the village was agog for a day or two till some fresh event caught its attention, and Polly's lapse sank into the commonplace of accepted things.

DO you know the love of the sea--the love that is sown when you are a child paddling in the little curly wavelets which play about the wet edge of the sand; that grows when you are brave enough to swim out into deep places; that strengthens when you are braver, and sail upon the harbour waters in a boat; that is deep rooted and ineradicable as the years pass, and you know your country's shipping as you know your city's streets? You have watched great liners glide in and out of port; you have seen your country's produce swung down into the holds of the cargo-carriers; and you hail as friend any craft, be she lovely yacht or shabby tramp, mighty battleship or fussy tug.

There is love in your heart for the wharves by day--for the hurry and the clatter, and the smell of them; and there is joy in your soul for their peace by night, when the ships are swinging to the gentle tide, like tired sea-birds rocking asleep.

[42] You know the sea in all her moods--in rage, in sadness, in sparkling gaiety; you know her rain-veiled, sun-kissed, wind-tossed, or dark. From her breast comes the cry of the seagull and the mollyhawk, and there rides the stately albatross.

Sometimes you are content just to sit quietly and listen to her.

If you know this love of the sea you will understand the magic of our picnic when we made our way through the bush that fringed the shore and ate our lunch beneath shady trees at the foot of the cliff, where the path goes steeply up to the village of Lolqangi. It was on a bright, calm day, when everything was crystal clear, the sea intensely blue, the sky cloudless, the beach dazzling white, and the bush a deep green. Away across the water rose the island of Opa. The throbbing of the locusts and the occasional cry of a bird broke the quiet; nothing else joined the drowsy murmur of the sea which spread away to the horizon. I dipped my fingers in the wavelet that rippled about the rock on which I sat, and smiled as I thought that thus was I linked with home. The sea and the five stars that are known as the Southern Cross are my companions; if I can see those things I am not [42/43] lonely. I have always known them, always looked for them, always loved them.

We climbed the steep track through the bush that clothes the face of the cliff. On that almost perpendicular path we clung to roots and creepers to support ourselves as we went. The climb was very tiring, and we were glad to sit down at the top, where we could get a wide view of the sea from beneath shady trees. Beautiful, wide, and lonely, it spread to the horizon. But even as we gazed the loneliness was dispelled, for a sail, as tiny as a butterfly, appeared on the horizon. It grew larger and larger as we watched, till it was like a graceful white-winged bird skimming the waters.

"Isn't it lovely?" I murmured.

"Yes," said the Gentle Lady. "If only it were not a recruiter!" she added wistfully.

I hardly heard, for my eyes were on the beautiful thing as it manuvred into the bay; and at that time I could scarcely have understood her wistfulness, for I had had no poignant experience with recruiting-cutters. I saw a yacht, and yachts were associated with happy days--then.

As we made our way back along the beach the cutter dropped her anchor. Quickly the [43/44] sails were furled and her boat lowered, and soon a crew of singing natives were rowing leisurely along the shore.

"They sound happy," I said.

The Gentle Lady made no comment. Late in the afternoon a shout went up from the cutter.

"Someone has recruited," said the Gentle Lady quietly.

After that there were almost always cutters in the bay, some flying the Tricolour, some the Union Jack, but all with the red-painted pleasure-boats, and the crews that kept rowing up and down and singing. I have seen seven such cutters at anchor in our bay at one time.

At night a great shout would come echoing up among the hills, followed by the rhythmic thudding of feet to the accompaniment of weird chanting. The sounds reached our house with startling clearness, and it was with difficulty I could believe that the performance was taking place out in the bay. The hills on each side seemed to act as a megaphone. I grew to dislike the cutters; they were noisy, and the natives on them had a brazen air that antagonized one. My dislike developed into contempt, and my contempt one day turned to fear. The change came about in this way.

[45] Among my schoolchildren were some sturdy youngsters, one of whom was a quiet, hard-working little fellow of eight or nine years named Ben. One day Ben did not come to school, and I learned that he had gone away on a cutter with his brothers and his father, who was a widower. The cutter that took them returned in a few months, and we asked:

"What news of Ben?"

The answer came: "Ben nu maté" (Ben is dead).

I was told that the work on plantations is hard, sometimes too hard for small boys, who are in some instances treated well, almost petted, as house-boys, but in other cases are worked too hard and die.

I looked round my class of chocolate-coloured children, saddened at thought of Ben; but when my eyes lighted on Isaac sad thoughts fled, for Isaac was one of those winsome little rascals, with the face of a cherub and the heart of a naughty boy. He was anything from six to nine years of age, with hair a little fairer and longer than most, eyes a little larger, and expression, when in school, just a little more deadly in earnest than his companions. For some reason best known to himself he wore a white singlet to school, snow-white at its first [45/46] appearance, giving him an air of wondrous cleanliness and surpassing innocence, and accentuating his cherubic exterior. As the weeks passed the singlet lost its freshness, but he kept it surprisingly clean. I used to wonder whether it was a garment dedicated to the mysteries of school. I never think of Isaac but I see him sitting in that little white singlet, breathing hard as he scratched laboriously on his slate, or gazing seriously at the blackboard, or singing. If he grew bored, he added variety to his labourers by stirring up his neighbours, and the consequent diversion seemed sufficient spur to his own flagging interest, for he would tackle his work with renewed zest. He lived at Lolqangi, the village at the top of the cliff; but sometimes he would spend a few days in our village, Qatnapui, and I would see him coming up the path bearing a large mummy-apple on his shoulder in quest of fish-hooks in exchange for his fruit, or find him playing with Jasper, the teacher's son. These visits, I fear were the result of hot tempter; they generally meant that Isaac had run away from irksome home authority. He was just a dear, naughty little boy, with a winsome face and a captivating manner that went straight to the heart of anyone who loved children.

[47] One day Isaac was playing on the beach. A recruiter's boat's crew, plying near the shore, asked him if he would like to go for a row.

He was taken to the cutter--a French one .

The recruiter laughed when the law was quoted to him: "the apparent age of fifteen;" "the consent of guardians," etc.

The cutter sailed away.

Nobody can give me news of little Isaac. Whenever I see a cutter now I wonder whether Isaac is among the little ones who have found the work too hard; and as the white wings move to and fro upon the waters, I see in them no longer things of beauty, but birds of prey.

Photo, Beattie, Hobart RAGA WOMAN AND CHILD, NEW HEBRIDES

"THEY fought the dogs and killed the cats." In childhood's days the Pied Piper enthralled us, and one never tired of that tale of the hordes of rats and the mysterious piper's power that wrought such terrible vengeance on the dishonest burghers. What joy there was in reading of the high-jinks of those graceless rats that "bit the babies in their cradles" and "licked the soup from the cooks' own ladles." Most poetry was so dreary, but this was a rapturous story of mischievous rats and merry children, and of grown-up people so naughty they had to be punished, a charming reversal of the usual order of events in our story-books. But when I found myself engaged in a sordid battle with the rats in the isles, the whole business was just intolerably dreary and not in the least amusing. They took us at a disadvantage, making a massed attack at the height of the hot season, when our resistance was at a low ebb and our sense of humour inclined to wilt.

I thought that I knew something of what rats were capable of doing when we were living at [48/49] Qatnapui, where it was necessary to keep all food strictly covered if we would save it. The cat we had preferred outdoor hunting, but she seemed to make our house less popular among rat-tenants than it might have been. We also set traps and regularly inspected them; we watched the pawpaws and kumaras and removed them before the rats attacked them--if we were lucky. One saw them in the kumara-gardens and sneaking up the pawpaw-trees, and the gory remnants of rat found in the yard told of the war that our cat was waging on them. Warned by the Gentle Lady, I was careful that no such disaster befell me as happened to a lady visitor to our island, who, recently returned from civilization armed with a new wardrobe, hung seven frocks up against the wall, most of them new. Next morning five of them were gnawed, and more or less ruined. But that happened at Qatnapui, where the rats were gentle of manner and few in number compared with the stalwart species that met us in North Raga. It was during our holiday in the north that I was introduced to the horrors of life in a rat-infested house.

The building was small, having been constructed from the wreckage of a larger house that was destroyed in a hurricane two years [49/50] before. It consisted of two rooms and a lean-to in which was a stove, and wherein we innocently placed our stores when we first arrived. In a few hours the sun turned it into an inferno and the rain flooded it. Philosophically we rearranged our household goods: we were on holiday, and we accepted trifles of that kind in the holiday spirit. The house, being hundreds of feet above the sea in an open, grassy space, was exposed to the scorching sun by day, a misery that was balanced by our joy in the glorious view at night.

The country was visible for miles around, and the sea until it joined the sky on the distant horizon. The tiniest breeze could find our hilltop. It was a refreshing spot, where merely the sight of the open, grassy paddocks was a tonic after the oppressive bush that had crowded us at Qatnapui. But the benefit of our holiday was likely to be nullified by loss of sleep, for our nights were made hideous by hordes of rats--"Grave old plodders and gay young friskers."

On the first night of our stay I was awakened by the noisy rattling of a bundle of wooded slats that had been left in a corner of the room. I sat up. It sounded as if a game of catch-who-can was being played by kittens careering wildly from room to room. Then some tins [50/51] clattered, and I heard a long "Sh-----" in the next room. The Gentle Lady was also disturbed.

In the morning we compared notes, laughed at our experiences, had traps set, and decided to be even more careful than usual of our possessions. Food must not be left exposed for a moment; everything edible was packed in tins and any insecure lids carefully weighted; all rubbish was punctiliously burnt. Yet in spite of all our care the hosts of rats held their nightly revels in our house. They were of an astonishing boldness. Night after night, with dreary regularity, I was awakened by vigorous gnawing in my room. All the rats that were caught in and about the house seemed to make no difference to the numbers that visited us at night. The nocturnal orgy went on, in spite of the effort of the native girls, who loved a rat-hunt, and stalked their prey with the zest of an Englishman stalking deer. Thus throughout our holiday we wrestled with the rat-problem with as little success as the Burghers of Hamelin Town; and--we had no Pied Piper!

Some months later we moved into our native house, where the rats at first were only mildly troublesome; but the few who had found us soon brought their friends and, in alarm, we [51/52] obtained a pretty little kitten from a mission station on another island. Her presence acted like magic on the rats, which had by that time begun revelling at night on the beams of the house, whence they descended to gnaw our shoes or eat the ripening bananas. Our brave little kitten hunted and killed them ruthlessly. But there was one kind of enormous size which even that fearless puss would not attack. The natives told us that it had been brought over in a boat from the opposite island by a former missionary--by accident, one may presume! Fortunately these creatures lived mostly out of doors, eating the fruit and vegetables.

Our kitten, named Bijou by the Gentle Lady, but by the natives called "Buss" (their best approach to "Puss") was a valiant rat-hunter till she discovered the delights of chasing lizards. That sport she could pursue by day or night, for there are lizards that love the day and others that love the night. There is the big, shiny, black qaso, so numerous in the hot season that they seemed to be for ever engaged in pursuing one another from the ceiling to the floor. As a rule they live out of doors, but our holiday house on the hill had been unoccupied for so long that rodents and reptiles, spiders and insects, had taken possession, and [52/53] living there was like living in a zoo. But even at Lamalanga, in the native house, Buss had only to run outside to the coral boulders in our yard to see several of appetizing plumpness, and in a few moments she would return with an ugly black creature in her jaws. Then there were many of the smaller varieties--no doubt with distinctive flavours--shiny, iridescent creatures that sometimes escaped her minus a tail. Of a night she could find occupation in hunting the mogope, a pale green lizard that lives among the shadowy beams during the day, and comes down in the dark to steal jam and other sweet things. Among their horrid habits is that of making an offensive clicking sound. Sometimes the creatures drop from the roof; and once, feeling a hairpin fall from my hair to my neck, I put up my hand to secure it--and secured a lizard! In time I became used to occurrences of the kind, though I never liked them.

Well, the lizards were an unpleasant nuisance, but they were utterly harmless in comparison with the ants. Against the ants we waged strenuous warfare, and exercised ceaseless vigilance.

"Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways and be wise." They taught me that line in a land where ants are few and harmless, and [53/54] live out of doors. There the ant was commended as an example of tireless industry, amazing ingenuity, and astonishing sagacity. Implanted in me was a great admiration for the little creatures, but in the isles that sentiment evaporated when I had to do battle against their tireless industry, amazing ingenuity, and astonishing sagacity. There were millions upon millions of them here, and it seemed as if they were all intent upon raiding our food.

If by chance the water were not renewed in the earthenware insulators upon which our food safe stood, or the kerosene not added, there followed a great to-do, for tiny ants in myriads immediately swarmed up the legs and overran our food like a brown tide that streamed up from the earth. Inevitably they found us. There was a never-ending procession in our living-room which marched along a ledge, ceaseless as time. Any food that was left for a moment on the table near their path was immediately smothered with the brown marauders. Reading the oft-told tale that borax gets rid of ants, I innocently believed it. But alas! our ants marched over it, made a path through it, and proceeded unimpeded on their way.

There was a big kind that lurked in dark places--among the stored yams for instance, or [54/55] inside our harmonium. That sort particularly liked fish. There was the destructive white ant, cause of endless anxiety, also to be fought, always and everywhere. There were ants only met outside, which bit savagely. They were a harassing, troublesome tribe, and yet, in spite of what we suffered by them, we must acknowledge that they do a wonderful work as scavengers. On night my eye was caught by a moving object on the floor; a dead lizard, about two inches in length, was being dragged along by a multitude of excited ants who ran about in great agitation, pushing and pulling that way and this in a foolish, disorganized fashion. As they seemed to be making little progress, I assisted by sweeping them out.

The ant is a mischievous fellow, but he cannot be entirely condemned, because he is busily clearing up rubbish; but it is difficult to see how one can temper one's condemnation of the silver-fish, the vandals that ruin beloved books and pictures till one is exasperated to tears. The horrid things wriggle into favourite books, and contrive to get themselves disgustingly squashed therein; they eat the photographs and pictures; every recipe for their extermination that we tried seem futile on our island.

Still more offensive is the large cockroach [55/56] that ravages clothes, books, and food. This horrid thing seems able to gain entrance to any cupboard or box that takes its fancy, and there it flourishes exceedingly, increasing and multiplying.

All these pests were a great nuisance and a subject of bitter lament; but if we did grieve at their presence in our midst, we rejoiced with an equal sincerity at the absence of the common house-fly.

So, in the midst of our persecution by rats, ants, silver-fish, lizards, and cockroaches, we could yet rejoice over our immunity from flies.

As a man of wisdom in the isles used to tell me when I grumbled, there is nothing like focussing on your blessings.

A-N-I-S. I looked at what I had written as the phonetic representation of the sounds given me. I said it to myself slowly and then quickly in the hope that I might thereby solve the puzzle, but in vain. I gave it up. It sounded like no English or native name that I knew.

"What does A-n-i-s represent?" I asked the Gentle Lady. "I have written A-n-i-s, as that is what it sounded like to me."

"Earnest," she answered promptly.

"Oh!" I gasped, dismayed at my dullness. How extraordinary it seemed to endow a child with a name that nobody on the island could pronounce correctly! I reflected later, however, that they were probably as nearly correct in their pronunciation of that name as I in some of theirs; and, moreover, they were apparently satisfied that they were pronouncing it as we did.

I had a somewhat similar experience with another name, but on this occasion had the satisfaction of solving the puzzle. I was admiring a fat little baby in his mother's arms. I asked the usual question:

[58] "What is his name?"

"Sémis."

"Sémis-----," I repeated, rolling it about in my mind in search of a clue. "Sémis-----." I thought I had found it! "Oh yes; Simons!" I exclaimed in the manner of a discoverer, remembering their custom of naming children after missionaries.

"No! Sémis!"

"Sémis?" I questioned doubtfully.

"Yes; Sémis!" said a boy who was standing near by; and from all sides "Sémis!" was repeated emphatically to the stupid white person.

I pondered, and light dawned. The Raga folk cannot pronounce the letter "J," but turn it into a kind of "S."

"James!" I exclaimed.

Delighted smiles rewarded my unusual display of intelligence.

There is in the islands a fashion of choosing a Biblical name at Baptism to add to, or in some cases supersede, the native name. In the case of modern babes born to Christian parents the child has often but one name, and that a foreign one. When the name chosen cannot be correctly pronounced, they retain the original spelling with the new pronunciation.

Many of the younger children call one another [58/59] more commonly by their native names than by those of their Baptism. For instance, a very important young person of North Raga, a small boy of eight or nine years, who will be the most powerful chief on the island when he comes of age, was known to me as Matthias. But I found that his young friends called him Tabé. The former is his Christian name and the latter his native one. He is a handsome, sturdy little fellow, possessed of great natural dignity; his voice is very deep, his gaze steady. He may be a little spoiled by the attention paid him by his elders, but among his boy friends he is on a level with the rest. He comes with his companions on the days when the merry crowd from Agatoa troop down the hill to school.

One day, during a singing lesson, when we were tackling a hymn, I noticed expansive smiles spreading over the faces of the boys near Matthias. On asking for an explanation, I learnt that the cause of the amusement was Matthias' singing.

"Ma lol mahantai" (He is singing badly), said one candid critic, who, though among the special chums of Matthias, was grinning broadly.

Now the singing was as a whole so far from melodious that it ill became anyone to criticize [59/60] his fellow. However, some had an idea of the tune, and these found the little chief's deep monotoning funny. At the criticism of his singing a dark flush swept over his face and his eyes blazed. I thought it well to deliver a homily on the value of the mere effort, no matter what were the results, and gradually the fire died down in Matthias' eyes.

In the Raga language, Tabé means "love"--a rather beautiful name for a chief who will be looked up to for guidance and example. I like to think that in the years when Matthias will rule he will be full of love for his people. At present he lives the ordinary life of a Raga boy, with a little more prominence at feasts and dances than is accorded the rank and file, but just one of the crowd at games and lessons. He usually goes about with a throng of small boy friends. It was with such a crowd that I first met him. He and his friends in turn came forward, politely shook hands, and then sat down to talk, frankly telling me who was who. So and so, the son of such and such, from this village or that.

If I asked one of them his name there was a pause, and then a friend proffered the information. I put the hesitation down to shyness. However, as the months passed, I found that [60/61] this was a rule; no child would tell me his or her own name. Quite intelligent children would look really shocked at the question, hang their heads a little or, if girls, disappear into the shawl, or qana, that is worn over the head by the women of the north, and all my queries and coaxings were fruitless. A neighbour would whisper to the questioned child, and then give the answer in his stead:

"John Sumu, son of Michael Lani!"

Occasionally there would be a talkative busybody in the class who loved to dispense information concerning her friends, and for her presence I was always thankful.

This personal reluctance, then, was not caused by shyness or misunderstanding, but by a well-recognized convention. Telling your own name is one of the things that is not done. For they do not use names with our easy freedom; there are rules to be observed, and the names of certain relations may not be uttered. In Central Raga enlightened women of good education, instead of naming their husbands, will say: "the father of my child."

This peculiar objection to saying who you are leads to awkward situations at times. There was a man of North Raga named Paul whom I knew quite well, and always easily recognized [61/62] by his fine red beard. The colour was due to bleaching by wood-ash, a very popular way of treating the hair. One day a man came to speak to me. I could not remember him, and asked him his name. He became mute, and stood there looking reproachful and a little offended. I was busy, and nobody was at hand to help us in our dilemma, so he turned silently away unidentified. When he had gone I asked a girl who had met him as he was leaving who he was. She said he was Paul. Well, he had a jet-black beard in place of the flaming red one by which I had always distinguished him. Could I be blamed for not knowing him? He had been at school at Norfolk Island for years, and for many years since then had been a teacher, yet even such a one could not bring himself to transgress his native etiquette for my enlightenment. But I still think that my rudeness in asking him his name was in the circumstances pardonable.

SOME incidents of very little significance impress themselves vividly upon the memory. For instance, I have a very clear picture of my first sight of Clarice. It was on a hot Sunday. The women of the village were grouped beneath the shady trees in the church grounds, waiting for the bell to call them to service. Leaning against a tree-trunk was a tall, good-looking girl wearing a bright red dress. There was in her some quality of youth or personality that attracted me, and I asked about her. I was told that she was already a widow, though only about seventeen years of age, and had come down from a heathen village in the hills with her mother, father, brother and sisters to settle at Qatnapui and attend the Mission-school. The father and brother had wandered down from the hills when food was scarce after a severe hurricane, had stayed about the place in an uncertain fashion for some time, and finally built a house and brought down their women-folk.

Clarice came to us as a boarder. She was high-spirited, vivacious, quick of intellect, with [63/64] a strong vein of conservatism running through her nature. In that she was a true daughter of her people, who cling tenaciously to the customs of their fathers. She knew only the speech of Central Raga, and our teaching was in that of the North, because the translations were printed in that tongue. At that time my knowledge of the language was very sketchy, and there was some difficulty in picking it up, since we were living just then in Central Raga, and the few North Raga girls in the school were new and very shy. Clarice, however, began at once to learn the North Raga language, and because at first her vocabulary was small, I picked up much more from her than from the other girls.

Photo, Beattie, Hobart ON THE ROAD TO ATABUL It is probably this same fact that makes talking to children so delightful to the beginner. Though their range of words is limited, there are no weaknesses of construction. To the white man it is an unique experience to hear tiny toddlers using faultless grammar and uttering the dignified phrases of their elders. For no baby-talk is heard there. However, I did not experience that joy till we moved to North Raga, because the children of Qatnapui know very little of the North Raga language, and as I knew nothing at all of theirs, we were driven to [64/65] use an international langue--the language of smiles; and that served very well.

Among those children were Clarice's two little sisters. Both were plump, and both had a suggestion of mischief in their bright dark eyes, but the younger, Bertha, was especially winsome, because she would sing to me in a funny little piping voice. When my class of earnest brown infants had been writing letters or learning sounds with the solemn concentration of their kind for a long enough period to warrant an interlude, we lifted our voices in song, or made a brave attempt at it. There was one hymn beginning "Ginau gaha tam gitae," which was a translation of "All things bright and beautiful," and was a great favourite. They liked it, and learned it easily, and some of the more daring spirits would stand in front of the class and sing a verse alone. Among these was the wee Bertha, who (for a native of Raga) had a good ear for music and a sweet voice. When I told Clarice of little Bertha's singing, she smiled with sisterly pride. For months the little girl came regularly to school. Then one day she was absent; and the next day, Thursday, her mother carried her up the hill to us; she was feverish and weak. We did what we could for the sick child, and then [65/66] the distressed mother carried her home again. Early on Saturday morning a message came to us: Bertha was dead. Clarice in deepest grief went flying down the hill.

Word went up to their old village, and mourners came down from the hills to wail with the bereaved family.

My class was dulled. I missed wee Bertha. I missed her tiny piping voice; I missed her bright dark eyes that would light into smiles, her little brown hands that tried so hard to write. She was the first brown baby I had lost--wee Bertha whom they buried in Clarice's bright red dress. Yes, Bertha's shroud was the gay frock that Clarice had worn when I first saw her on that sunny Sunday morning months before.

After the funeral Clarice came back to school and settled once more into our routine. Then romance sought her again.

There was among our pupils one Eliza, our most advanced scholar and member of a clever, well-educated family, the members of which spoke English as well as Mota, and at least two of the Raga dialects. Well, Eliza was sought in marriage by one Edwin, a teacher and something of a dude. But a hitch occurred, and the payment or pledges were not fulfilled. Then [66/67] he saw Clarice, and he thought that she might suit him as well or better. Is a Melanesian's mind ever assailed by doubts as to his fitness to be the maiden's husband? I don't think so: the honour is the lady's. Edwin was torn between the charms of Eliza and Clarice. In his perplexity he sought an interview with the Gentle Lady, told her that he thought of marrying Clarice, and made enquiries as to her suitability for such eminence; for the Melanesian teacher is sensible of the dignity of his position, and is, as a rule, anxious to choose a wife who will help him uphold it. Meanwhile the two girls whose charms were troubling Edwin went on serenely with their lessons, and were apparently quite happy together.

But early one morning, when the grass was still sparkling with dew, a young teacher of great influence and outstanding personality arrived, and asked if he might talk to Eliza and Clarice. Permission was given, and the interview took place in a small native building near the house. I was having my early morning tea on the veranda, and heard the words, "I come with a message from Edwin," and then the deep hum of his masculine tones went on for some time. When, later, the two girls emerged, Clarice walked with head hung down [67/68] and a gloomy expression on her face, while Eliza, with head erect, smiled about her.

It seems that the two girls had been disagreeable to each other, and Edwin, hearing of it, had sent word that if they continued quarrelling he would have neither of them! Judging by the demeanour of the culprits after the interview, contrary as it may seem, Eliza had probably had a "wigging," while Clarice saw victory ahead. The psychology of the Melanesian girl is not the psychology of the white girl. The Melanesian world seems a topsy-turvy place at first, because nobody seems to do what you expect them to. But after a while you get used to it, even if you never understand it.

While Edwin's choice was still uncertain, he left Qatnapui for the village where he taught, making the journey in his canoe. On the morning of his departure he was present in church at Matins, and afterwards, in the church grounds, he very solemnly shook hands with me first, and then with the admiring school-girls whose impressionable hearts were all a-flutter at the going from us of this hero of romance. As he turned to go down to the beach, and we moved up the path, I saw Clarice and Eliza shyly peeping from behind the same orange-tree. The only people with [68/69] whom Edwin had exchanged no word or sign of farewell were these two young women. What seemed still more odd was that apparently they had not expected it. By that time I was aware that I knew nothing at all about Melanesians.

Well, in the end Edwin close Clarice, and someone else chose Eliza. Both are contentedly married, though there are the usual rumours of domestic quarrels. Such are common, however, and mean little among a quick-tempered and impulsive people who have yet to acquire self-control.

When I was last at Qatnapui I saw Clarice. She was sitting among a crowd of women, and because she had grown plumper, and had bleached her hair to the reddish shade often affected on Raga, I did not at first sight know her. The sparkling schoolgirl, the girl of the red dress, was gone, and in her place was a placid young matron. But whenever I think of Clarice I see a girl leaning against a tree in the churchyard, wearing a red dress, the dress in which little Bertha was buried.

IN great natural disturbances, such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and hurricanes, there is a savagery of wanton destruction and inexplicable ruthlessness that prompts a cry of protest to Nature. Surely some day science will enable men to forecast these disasters and perhaps counteract them, so that they will cease to be calamitous. Meanwhile we go on as men did in the days before they knew anything of antiseptic surgery, enduring what we see no means of escaping.

It is thus with us in the New Hebrides, where we become accustomed to the awesome presence of active volcanoes, to the terrifying tremors of the earthquake, and to the menace of the hurricane. The dread of the last is the greatest fear in the isles.

You have not the proper respect for hurricanes until you have experienced one. Before that, when a high wind rises during the hurricane season--November to May--you wonder at the careful preparations made, and think the precautions taken are somewhat extreme, and when the wind drops the relief of your colleagues seems [70/71] greater than the experience justified. But when you have weathered your first hurricane you understand, because you know.

During the hurricane season, which is also the hot and the wet season, cutters are rarely seen among the islands, for throughout that period the weather is treacherous, and the terrible wind may come almost without warning.

Hurricanes occur at the season when most damage can be done to the food supply of the people, for the big yam crop of the year ripens during these months, and also that of the breadfruit. A long spell of dry weather is an ominous sign in the hot season according to the Experienced Person, and certainly hurricanes often come after such a period.

When I first landed on Raga the island was just recovering from a very severe hurricane of eighteen months before. That wind the natives said was the worst they could remember. Little did they know that they were to experience one worse still before many months had passed.

Even after a year and a half there were many signs of the disaster that had befallen. At Qatnapui a small church had been built out of the ruins of the former large one which the wind had destroyed, and houses had to be rebuilt. Great trees had been smashed, and [71/72] in the bush a creeper had overrun everything, climbing to the tops of trees, hanging in great swinging curtains, and effectually obscuring the outline of the whole as with a shroud.

In North Raga the destruction was even greater. There both the Mission-house and the big wooden church were razed to the ground; in every village houses were destroyed, and in most of them the church and school-buildings also; the food-gardens were swept bare; the yam crop was ruined; and the people, after repairing their garden fences to keep out the pigs, and doing what they could to make their houses habitable, spent their days in the bush searching for wild yam, which is appropriately named by them famine food.

The Condominium Government, whose headquarters are in the south of the group at Vila, distributed a certain amount of rice, and actual famine was averted; but the times were hard for the people. Soon, however, they set to work replacing their destroyed churches and schools with temporary structures, which in turn would give way to bigger and better buildings as soon as the broken sago-palms could produce enough leaves for the thatch and the reeds for the walls had sprung up again. The following season passed in harmless tranquility, [72/73] and the next had almost gone when, on the last Sunday in March, a great gale rose and we feared a disastrous wind.