|

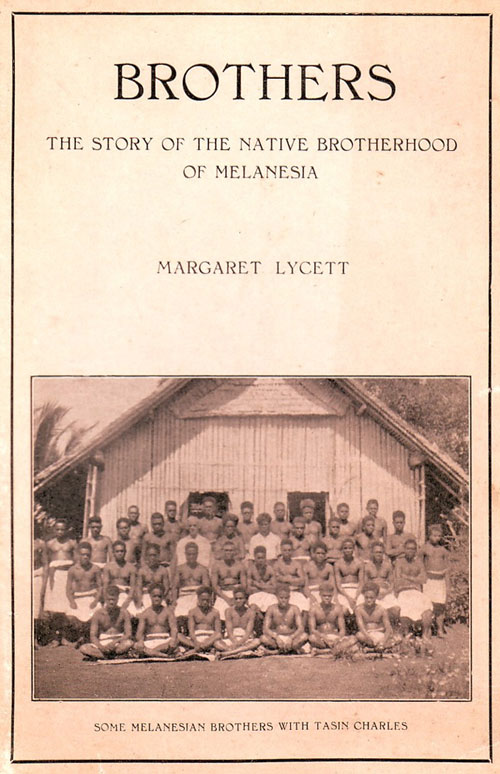

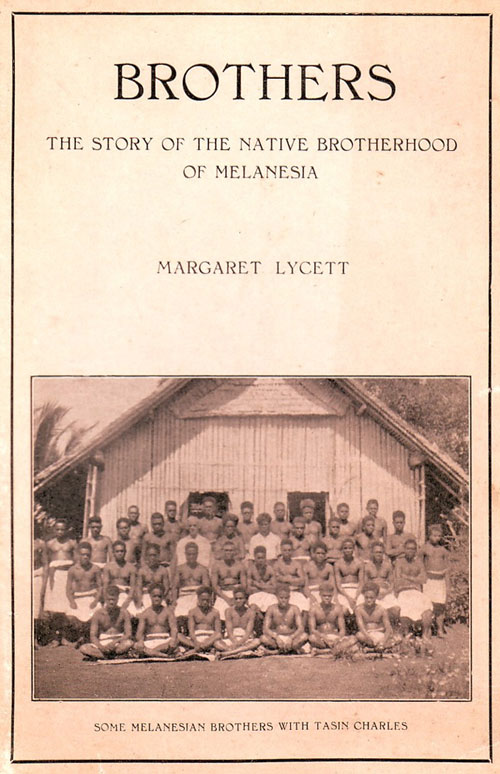

BROTHERHOOD OF MELANESIA SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. 2 1935 |

I. HOW IT BEGAN 1

II. INI 6

III. PROGRESS, THE FIRST STAGE 32

IV. THE PRICE OF DISCIPLESHIP 36

V. THE BROTHER AT WORK 42

VI. "THEN COMES THE END" 60

The Melanesian Mission Southern Cross Log, a monthly magazine published in England.

O Sala Ususur, a Diocesan chronicle, written in an island language, to which the natives are the principal contributors.

Annual Reports of the Bishop of Melanesia.

Translations of private letters written by the Brothers themselves, and other letters from the Islands.

All the direct quotations are taken from these sources except where otherwise stated.

The writing of the book was due to the initiative of Miss Tyas, who also helped considerably in its composition.

[1] CHAPTER I HOW IT BEGAN AT the Dedication of Southern Cross VI. (1932) the Archbishop of Canterbury described the work of the Church in Melanesia as "the most romantic and the most adventurous of all the missions of the Church." Those who know anything of Selwyn and Patteson would undoubtedly re-echo the words, but there is always a tendency for us to think that such descriptions belong to the past. We are so busy with our own personal concerns that we fail to realize that in a quiet way the adventure continues, the difference being that to-day pioneer native Christians are leading the way and showing to the world that zealous love that should always be apparent in followers of our Blessed Lord.

For the sake of those not familiar with the beginnings of the Christian story in the South Pacific, it is perhaps necessary to give some little introduction.

As first Bishop of New Zealand, G. A. Selwyn was given charge of the islands of the South Pacific. In his early voyages he realized that the only way to make Melanesia Christian was by training native leaders to be evangelists to their own people. Boys who were sufficiently daring were taken to Auckland for this purpose, but it was found necessary to return them to their tropical homes before the rigours of winter set in. Such short periods of influence were obviously unsatisfactory, and it is therefore not surprising that after the formation of the separate diocese of [1/2] Melanesia, Patteson, its first Bishop, should seek some place in the Islands themselves which could be the centre of his labour during the New Zealand winter.

The island of Mota in the Banks group is one of peculiar charm. There is one small beach, but, for the greater part of its twelve miles of coast, the white surf beats against the rugged coral crags that rise abruptly from the deep blue waters of the ocean. The overhanging trees and climbing plants give promise of the rich fertility of the plain, where breadfruit, coco-nut trees and bananas grow in profusion, and from the centre of which, covered with thick tropical bush, the slopes of a volcanic cone climb to a height of nearly fourteen hundred feet.

There are several villages of from ten to twelve dwellings, all after a similar pattern. The houses, built round an open space, are of bamboo, their side walls not more than two feet high, while the sloping roofs of palm leaves almost touch the ground. In each village there is one long narrow building, the "gamal," which serves as a club house for the men, where the bachelors sleep, and where the men cook their food in ovens made by lining hollow places in the ground with stones.

Here are none of the gruesome sights that met the eye in the Solomon Island villages, where the skulls of human victims frequently adorned the ridge poles of the houses. The people, almost devoid of ornament and tattoo markings, are good-looking and very attractive.

In such a place the Bishop could continue the training of his pupils in a climate suited to their natures, [2/3] and in that atmosphere of superstition and jealous fear that surrounded their lives; here he could make those positive points of contact on which must be built the structure of Christian teaching.

After a long but industrious voyage in a very slow vessel’Äîthe variety of the languages necessitating six or seven classes daily’Äîthe Bishop and his staff of one priest and a layman, together with the school-boys, were given a warm welcome from the people of Mota, who helped them to carry their belongings up the short steep path to the village. A little carpentering in a climate of such a nature that nails left exposed for a few minutes would burn the hands, and all was in order for the school. When this was established, the Bishop visited the villages on Mota and on other islands of the group.

It needs an active imagination to appreciate the steadfast faith, persistent courage, and selfless devotion that were necessary to success in such district visiting, for the young Bishop slept on the floor of the village club houses among thirty, forty or fifty naked fellows, and frequently had to face with unruffled calm the threatening arrows of those with whom he would make friends. Here were conditions that the missionary in Melanesia is rarely called to face to-day, but there are others that persist, and in these, too, Patteson set a perfect example. When he returned to the school, anxiety caused by sickness, the death of one of the boys, fever attacking first one and then another, a wearisome ear-ache entailing sleepless nights and giving rise to fear lest deafness should hinder his language work, and through all, the consciousness of problems innumerable in the thousands of villages [3/4] waiting for help’Äîsuch were his problems. And similar problems still test the missionary's capacity for cheerful endurance and sound judgment.

There is no doubt that the Spirit of Wisdom and Understanding was on Patteson. This was shown in his quick recognition of the problem, the agelong problem of turning spears into pruning hooks. He saw old customs being broken down, superstitions losing power, fighting ceasing, and saw, too, that in a climate and upon a soil where there is little need for man to bestir himself for his daily bread there was danger of these changes leading to an emptiness that would result not only in increase of indolence and gluttony, but what was even worse-a loss of that zest which is the spice of life. "And the mild, uncomplaining creatures yawn and await death" (R. L. Stevenson). Surely this could not be described as life more abundant. A profession of Christianity was worse than futile unless with patient persistence it brought about a lively transformation of the whole of their social and domestic conditions. Patteson had a close-up view of what Selwyn had seen at a distance when planning for native evangelists trained in Central schools to be the leaders of the people. In the years that followed, Patteson's pupils were ready to lead the way among their own friends, and before his martyrdom, the Bishop had the joy of ordaining the first Melanesian Deacon. It has always been the Christian teachers, trained in Auckland, at Norfolk Island or later in the Central schools of Melanesia, who have demonstrated to the world that the exquisite craftsmanship that had been used to construct and decorate with inlay work and carving weapons of destruction, [4/5] can be turned to the making and ornamenting of Christian churches and Altars; that the true warfare is against dirt and disease, selfishness and lust; that orderliness and holiness go hand in hand.

[6] CHAPTER II INI LIKE most great movements, the Brotherhood of Melanesia began simply, in a small way; as in all living organisms growth has involved some development and change; and again, as in so many movements, its very success is raising problems almost more hazardous than the difficulties of the early days. The Brothers need all the continuing grace of the Holy Spirit that He Who "has begun a good work may perform it till the day of Jesus Christ." The rest of the Church in Melanesia needs the same grace, that the trail which has been blazed may never be overgrown for lack of those to lay down and mark out the broad paved road on which many shall walk to the city of the Great King.

It began as similar movements have begun throughout the ages. Missionary work is a logical consequence of any real experience of God; the second great commandment inevitably follows the first. The early Apostles were men caught by a compelling force; on a mount of Vision they had realised unmistakably that their Friend and Comrade of three years past was none other than their Lord and God. And when they found what God was like, realizing the fathomless depths of His Heart of love and all that He had done for them, they were moved irresistibly to share the Good News with others, that all men might bring their gifts and worship Him. It was as simple as that. The [6/7] evidence of Christianity is the life, and those who have caught even a glimpse of God's beauty and loveliness, have realised even a little of His divine forgiveness and care, have known, however dimly, the joy of His fellowship, cannot rest content until all come to share that vision, that love and that companionship. Here always is the authentic Christian note. If Christ means anything, Christians have to irradiate joy, and the measure of their zeal for Him is the measure of their eagerness and willingness to bring all men to His light, to offer His way as the solution of every ill.

It worked out like that in the days of the Apostles, and has continued to do so in the Saints, down to our own days. "Whenever Christianity has struck out a new path in her journey it has been because the personality of Jesus has again become living and a ray from His Being has once more illuminated the world." (Bossuet.) That is because men, seeing in Christ the heart and purpose of God, have been so filled with gratitude that they have been impelled to do what they could, and it seemed so very little, to say "thank You." They have learnt to understand "down to its very depths, the theory of thanks, and its depths are a bottomless abyss." (G. K. Chesterton: S. Francis.)

In many respects, allowing for differences of time and place, the Brotherhood reminds one of the Franciscan movement of thirteenth century Europe. Like that, it began with the great change which dedication to God makes in the life of one man, followed by the gathering round him of a group of men similarly bound. Like the Franciscans, the Brothers go to those whom the Church has not yet been able to reach, bringing comfort and healing for body, mind and [7/8] soul; like the Franciscans, with "Lady Poverty" for wife, and service, love and joy for ideal, they work for their living, taking no payment except food and a night's lodging; they preach in untouched places or among those who have grown lukewarm; they go teaching to distant and strange lands; they visit the lepers and tend the sick. Like the Franciscans, they are "social yet unworldly, they serve, yet for no reward, labour, yet not for gain, and live in joy and love." (G. K. Chesterton: S. Francis.) They are like them, too, in the visible change which by the power of goodness and by service they have effected in the lives of hundreds of men.

. . . . . . . . . . .Ini Kopuria, the first Elder Brother, was born near Maravovo on the island of Guadalcanar in the Solomons group, soon after the beginning of the present century. Guadalcanar is a large island, more easily accessible than some, and therefore he was influenced to a peculiar degree by the forces shaping Melanesian history. He came under Christian influence early, for while quite a child he was baptized at Maravovo from a small school for boys to which he belonged.

The Ini of these and later schooldays has been described as "a very undersized, narrow-chested, high-shouldered child who never seemed to grow any bigger; with a queer old-fashioned face, and a voice that was seldom silent for long." There seems, however, to have been something very attractive about him, and first at S. Michael's, Pamua, and then at Norfolk Island, to which he went from the village [8/9] school, he was a general favourite, probably not escaping unscathed the temptations inherent in such a privileged position.

He seems to have been intelligent, interested in his work, and eager to enter into the varied activities life provided. There is evidence that he possessed depth of personality, a thoughtful disposition, and something of the stuff from which martyrs are made, mixed up with an almost ludicrous sense of childish self-importance, which, in a less healthy nature or with injudicious treatment, might have led to priggishness. The story is told of how Ini once made a vow to keep silence during Lent. On Ash Wednesday after Chapel he presented himself, contrary to rules, on the verandah, offering in self-conscious silence to the white teacher a letter which must have given him tremendous gratification to write. This explained the nature and strictness of his Lenten vow and asked that he might be excused repetition and questioning in school during the Lenten season so that he might not be tempted to break it. Probably at bottom there was a pure motive and real desire to give up something that he dearly loved, but a popular little boy could not fail also to find a certain satisfaction in the stir such conduct would cause. Another characteristic, prominent in the Ini of later days, is evident in the sequel’Äîthe will-power which, consecrated and directed, has carried him through many difficulties and dangers since his new work began. The situation was explained to the Bishop, who showed Ini the unwisdom of such conduct, suggested methods, better because less inconvenient to others, of showing his love for and desire to serve God, and released him from the vow. [9/10] But in vain; Ini refused to speak, and for three days he held out. It might have been obstinacy, but while obstinacy selfishly applied becomes weakness, placed on a solid foundation of love and service it can become a driving power, capable of resisting or overcoming great obstacles and heavy odds. Certainly here was a boy who would stand out among his fellows and would probably not tread the ordinary path.

These years at school, in daily contact with Christian white men and women, proved the most formative in Ini's career and character, and so it is perhaps not irrelevant to review in more detail the kind of life he led there.

S. Barnabas' School on Norfolk Island, the forerunner of the later schools in the islands themselves, had been established by Bishop Patteson as the training-ground for Melanesians who were expected to return as teachers to their own islands. The boys who were brought by the mission ship, the Southern Cross, from the various islands, remained at school for two years, after which they might return home, either permanently, or for a six months' holiday before a further period of training.

Life was disciplined, each of the seventeen daily bells demanding some action promptly carried out. Work in school, in garden and field, in house and kitchen, in workshop and dairy, formed part of the teaching, while time was given when the boys were as free as if they were at home. Saturday was a whole holiday. Then they might fish or attend to their own gardens, occupy themselves in their own little native house, or play football or cricket. White and brown lived and worked as a community; meals were taken [10/11] in common in the hall, for Patteson's plan of the education of the native mind through constant contact with his white friends at work or play has always been carried out, and at all times the boys found, and were encouraged to find, men ready to help them with any problem that might arise. And daily, morning and evening, a bell called to prayers in the beautiful Patteson Memorial Chapel. This is unique not only in its place (it is not the building one would expect in the heart of the Pacific), but also in its time. Built at a time when architecture in England was at a very low level, the Chapel is yet perfect in every detail. The materials are rich, yet used with simplicity and restraint, and there is a combination of European art with native inlay work on altar and stalls, which would have rejoiced the heart of Bishop Patteson, who both delighted in the treasures of Europe and also discovered the beauty inherent in the minds of his Melanesian boys. (C. M. Yonge: Life and Letters of J. C. Patteson.)

In such a building, where the very stones breathed praise and thanksgiving, Ini would come under the influence of an atmosphere vibrant with prayer. Only a few years before Ini's time there, a visitor to Norfolk Island, one with considerable experience in schools, described S. Barnabas' as "the happiest school I know." He added, "They accept God for all day and all the week, yet the last thing you would say of them is that they are gloomy. I feel that a religion which so moulds their behaviour in Church and lets them face the round of the day's doings with merriment and manliness is solid and genuine Christianity." (Canon P. Stacy Waddy: A Visit to Norfolk Island.)

[12] It was expected that Ini on leaving school would become a teacher among his own people. But he could not settle. He may have been spoiled, having had his head turned by wider contacts which made daily routine in a familiar village seem dull and colourless. Or there may have been some more fundamental reason; a discontent which was divine, a glimpse of and a longing for some great thing but dimly seen; perhaps even the knowledge of the sacrifice involved which he dared not face. In the lives of all those who are called by God to do great things for Him there seems to come a time when everything is confused; when the life they lead is utterly inadequate for their needs, and yet when they either cannot or will not see the way where satisfaction alone may be found. Perhaps Ini was restless because he was facing the night of the soul; what he had been taught, his beliefs and upbringing, being tested in ways more subtle even than the temptations present in fresh contacts with heathenism’Äîthe questioning of his own mind as to the truth of it all, whether it was after all worth while, and if not, what was.

Whether or not these struggles were going on almost unconsciously, the fact remains that Ini disappointed all those who had set such high hopes on him by enlisting in the Native Armed Constabulary. Yet, looking back now in the light of what was to follow, it is hard to say that his step was not the right one. Would S. Paul have been the father of so many Churches had he not first been the fierce persecutor of the Christ? Would S. Francis have reached such heights of love and compassion had he not first shrunk from sight of a leper? Would Ini Kopuria have [12/13] become the man he is and have been enabled to have such wide vision, in particular to see the needs of Melanesians detribalised by plantation life and Government service, had he not himself served in the native police force? Whether it was a stage planned for him in the divine scheme of things, or merely man's own waywardness, certainly it was an experience which the Holy Spirit has blessed to the enrichment of the Church and to the beginning of a work more far-reaching than that which any village teacher, almost inevitably narrowed in some respects by the nature and conditions of his work, could have achieved. Melanesia needed not only white men but also a Melanesian to see beyond the confines of his own village or island; grace was given to Ini to be the man who should give a lead.

His life in the Police Force was at first unhappy. The strict discipline irked him and conditions were foreign to his experience. He felt cut off from his old surroundings and heritage in a way in which he had never been at school where life was as far as possible run on native lines, leaving behind only those things contrary to Christianity, consecrating and continuing what was good in native life. He was impatient and dissatisfied, even to the extent of asking the Mission authorities to secure his release from his obligations. This they naturally refused to do, and Ini showed his solid sense by settling down and earning a reputation for smartness and efficiency. The value attached by the Police authorities to his influence is shown by an incident which occurred after he had left the service. In 1927, at the height of the excitement caused by the murders on Mala, Ini was asked by the Commissioner [13/14] to return to the Police Force in order to go to the island and attempt to put matters straight. The fact that he was asked to do this shows the esteem in which he was held, and his attitude to the request throws fresh light on his character. He explained that he was no longer his own master and must consult the Bishop. To the Warden of the College at Siota, however, he explained himself more clearly. "I could not refuse outright, but it would be bad for me to go to Mala with a rifle. I shall probably want to go later with the Gospel."

In 1924, while a Police boy, he met with an accident and was ill for some time in hospital at Tulagi, the Government centre in the Solomons. It was then that the light to which he had been groping came to him, a fuller knowledge and acknowledgment of Christ. He recognized that only in the service of Christ could true peace and happiness be found, and he realized also just how the implications worked out for him. Not for the first time, a man had been "put on his back to make him look up." His illness gave him opportunity for deep reflection, and an article in the Mission paper O Sala Ususur, suggesting the possibility of a life consecrated to God's service, pointed the direction he should take.

As he himself wrote in a letter to his Bishop at this crisis, "Before now I have often thought, 'what is to be my life's work here?' and I was convinced that it was certainly that of the police, but I was mistaken. God has called me from following that manner of life, and in my pain and sickness God has shown me that I should see clearly that it is not my duty to live as a policeman but to declare the kingdom of God among the heathen."

[15] Then follows the authentic note and motive of consecration ringing in the heart of this primitive man in Melanesia as it has rung down all the ages. "He made me to remember 'your life is Mine, and God can do as He wishes with His own.'" "Whom shall we send and who will go for us?" "Lord, send me." With the realization of God and His purpose came this man's response. Ini offered himself in complete surrender. He acknowledged the Father's right to direct the creature He had fashioned, and dedicated his life, if he should be restored to health, to the service of the heathen, particularly on his own island of Guadalcanar, vowing himself to celibacy, and his property "to feed the flock of Christ."

This being done, he quietly waited for guidance as to the next step.

"Then soon afterwards again I sat and thought, how shall I begin to labour in God's kingdom? I thought of the Kingdom of God as a garden. There is only one Garden and one Lord of the Garden, but the workers who are wanted in the Garden are many. I thought, I need fellow-workers besides myself to help me; it is too hard for me alone."

The Brotherhood was foreshadowed.

Ini was fortunate in having as his Bishop one able to understand his dreams and to see their great possibilities; one who was convinced of his sincerity, and willing to give him just that sympathy and encouragement for which a man longs when he has passed through a great spiritual experience and comes down from the mountain-top to work out his vision in terms of ordinary everyday life. Ini was very young, only twenty-three; he had shown himself impatient before, [15/16] and youthful impatience is not immediately disciplined by great dreams of service’Äîoften it is so intensified when the stumbling-blocks appear that the vision itself is choked and dies. He had many practical schemes embodying his vision; his own infectious enthusiasm was needed to kindle the hearts of other young men who were seeking ways of service, yet to achieve its fulness the movement needed just that wise counsel and ballast which an older and more experienced man could give. Youth loses much by unwillingness to profit by the wisdom of the generation ahead; the Brotherhood of Melanesia has been sane and successful, diffusing the Spirit of Christ, largely because older and younger men have been willing to recognize each other's peculiar function and powers and to blend them all for the good of the whole. Obedience to the white man perhaps came naturally to the Melanesian, yet Ini had always been a decided personality, and fresh zeal with the exuberant impetus of youth might have caused him to try his own way regardless of others. Instead, he put himself under his Bishop's orders, and the Bishop in turn, recognizing one who realized the responsibilities his experience had brought, was willing to leave much to his judgment. Indifference, failure to understand the young man when he wrote, even more than active opposition would have changed not only Ini's life and purpose, but the whole development of the Church in the Islands. Ini himself and the Brotherhood owe more than can be measured in human scales to the insight and wisdom of Bishop Steward in the beginning and to his self-effacing direction as Father of the Brothers in the early days when the work had been started.

[17] This was in 1925. After his decision Ini went for a time to the College at Siota, the administrative centre of the Diocese, for further study and experience as a teacher, then he returned to his native village to clear the site which he had given to the Mission as Headquarters for the Brotherhood when it should come into being. Tools for draining and clearing were provided from the school at Maravovo, and Ini made an effort to get help from all the Christian villages near. In this he was not as successful as he had hoped. The people made monetary collections, but few came to help in the actual work, and finally he was forced to attempt the task aided only by three others. Two of these were boys who wished to go to the school but were not considered suitable; in addition to the work of clearing which they carried out together, Ini also found time to teach them to read. His plans, however, had to be modified. Instead of the six houses he had hoped to build he had to be content for the time with one, and his longed-for chapel had to be left for the future.

On the feast of SS. Simon and Jude, 1925, standing under a large tree on this site, Ini made his profession before the Bishop, the Assistant Bishop, and one of the white priests, in words he had himself drawn up.

"In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

"Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy, Lord have mercy.

"Our Father . . .

"Trinity All Holy; from to-day until the day of my death, I promise in the Name of the Father, and [17/18] of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, and before Archangels and Angels, Spirits and Saints, and before the Bishop, John Manwaring Steward, Bishop Frederick Merivale Molyneux and the Rev. Arthur Innes Hopkins, representing the Church here in Melanesia, I promise three things. I give myself and my land, together with all that is mine, to Thee. I will take no payment from the Mission for the work to which Thou sendest me. I will remain Thy celibate always till my death. Strengthen me that I may remain firm, remain peaceful, remain faithful therein all my days till death: Who livest and reignest, Three in One God, world without end. Amen."

This act has been taken to mark the foundation of the Brotherhood and the day of the taking of the vow was chosen for the Annual Chapter. Conditions in the islands, however, postponed the actual gathering of the first Brothers and their first missionary adventure on Guadalcanar until the following Whitsuntide. The Southern Cross, the Mission ship, is the chief, often the only, means of communication throughout the diocese, and, at that time, she made two voyages every year. As Ini's promise was made in the concluding months of 1925, those willing to join him could only be gathered together during the first voyage of 1926, and brought to Siota when the ship returned there in May. Thus there was a pause before Ini could set out, as he planned, into the heathen bush. The time was spent in appealing for young men to join him. He went with the ship, making a personal appeal for recruits at the different islands she touched, at the same time making known his ideas in a striking contribution to O Sala Ususur.

[19] He began by sketching precisely the situation on Guadalcanar, detailing the heathen villages in the various districts by name, and estimating that, of the population of about 12,000, there remained three or four thousand untouched by Christian influence. Then the challenge was issued, based on the text in S. John, "And other sheep I have." This he developed on the lines that Christ did not seek only those in the fold, and it was the task of those already called, few though their numbers might be, to draw others to enter. "The door," he wrote, "is open for ever and cannot be closed." Then, thinking of the ship which plays so large a part in Church life in Melanesia, he saw it as the means by which the sheep should be carried to the fold. Ship and Fold were the Church, entered by means of the Wharf, Baptism. And on the ship were to be found both Master and Captain, with the Holy Spirit Himself as the Engine. "And the Engine is altogether lovely, It lasts for ever, It cannot get out of order on the passage to Heaven. The Engine lasts on, the Fire is always hot and cannot die out for It is eternal."

But the Ship needed workers. Some there were, but not yet enough. "As to the 'Sailors,' I have written how the Captain needs those other sheep on Guadalcanar, that small island (for there are many more throughout the world). He wants Sailors for a voyage to Guadalcanar (and also many more for other places), to bring into the fold those three or four thousand sheep in the ninety villages. The Captain longs to bring those sheep into the fold. He has said, 'They must hear My Voice and there shall be one flock and One Shepherd' . . . I the other young [19/20] man await you; any of you young men who can, let him come with me."

During the next six months, six other young men were found to venture forth with him. All were Solomon Islanders; three, Moffatt Ohigita, Dudley Bale and Cecil Logathaga, came from Santa Isabel; two, Maurice Manere and Hugo Holun, from Laube, and Benjamin Boko from Guadalcanar.

In the middle of May 1926 the seven met together, with the Bishop, at Siota, and rules were discussed. Several names were suggested for the band, but finally it was agreed to adopt that which most truly described the men and their mission’Äî"the Brothers," and such has accordingly been their title. When speaking they address one another as "Brother So and So," and their writing concludes, "So and so, a Brother."

On Whitsunday, May 23rd, after Evensong in the College Chapel at Siota, the Brotherhood was formally constituted for work among the heathen in the high lands of Guadalcanar. After the Invocation and the Lord's Prayer, the Bishop received the vows of dedication, binding for one year, and laying his hands upon each admitted him into the Brotherhood. Each Brother promised to remain unmarried, to receive no payment and to obey "those set in authority over them."

Prayer for the new Brothers and for the heathen, a hymn and the blessing closed the first stage in the history of the new movement, and opened the way to fresh paths, many of them as yet unthought of.

The next morning the Holy Eucharist was celebrated before the Ship carried these new "Sailors" to [20/21] Guadalcanar. On May 25th, they landed at Tambulivu and went to the House Ini had already prepared. A service of preparation for the Holy Communion next day occupied the evening. In it the Brothers were given an address warning them of the possible dangers and temptations in the days ahead, reminding them of Him Who had promised His Presence all the days.

After the Celebration and breakfast the next day the first Chapter of the Brothers was held with the Bishop in the Chair. Ini explained his ideas and an itinerary was planned. He was elected the first Elder Brother, and the annual Chapter was fixed for SS. Simon and Jude's day. The Southern Cross took them to the nearest spot to the road to the hills and there they were landed, knapsack on back, just before sunset. That night they were to sleep in the nearest village, to which the Bishop accompanied them; then by the light of the full moon he returned, commending them to Him Whom they would serve, and another great adventure of faith was begun.

What was the purpose of this simple setting out; what the ultimate significance of these young men's action?

The purpose was explicit in the Rule. The aim of the Brothers was to evangelize those people whom the white men found it difficult to reach; to preach the Word and to hold open the door by which teachers might follow and establish the Church firmly. It has already been suggested that communications within, as without, the Islands, are not easy. Even with a much larger white staff than is at present available, some places in the interior would remain difficult, if [21/22] not impossible, for Europeans to penetrate, at least until contact of some sort had been made with the inhabitants. The hardiest white man, the most experienced pioneer in tropical lands, needs more equipment for his journeying than the native who can travel light, sustain life on simpler food, and so be freer from material needs to attend to the spiritual work. Such an undertaking is pre-eminently for the young and the strong. Even they have had their manhood sorely tried in what followed, and more than one has prepared the way with his life. The Brothers aimed, then, at making such contact by persuading villages to accept and welcome a qualified teacher.

But the Bishop had another purpose in mind, when he considered Ini's scheme. Young men in Melanesia, no less than elsewhere, offer a problem. There is much energy and zeal for service, and had been little outlet for it. Not every boy who passed through the schools was fitted for the exacting work of village teacher; not all were prepared to accept its humdrum conditions after the life of companionship and activity to which they had grown accustomed; and the only other alternatives were plantations or government service, neither of which, as at present organized, fulfilled their deepest needs. In the Brotherhood there was a splendid opportunity for the young man who wanted to use his manhood in God's service to learn responsibility and to develop himself in the service of his fellows. And again, it provided a means of seeing if there were room in Melanesia for vocation to the religious life. If there are those in Melanesia for whom such a life is the way, then the Brotherhood offers them an opening in a land where as yet there [22/23] have been few opportunities to exercise vocation of any kind.

It is impossible to assess its ultimate significance. It is significant of the fruit of Christianity, the power of the Holy Spirit, and perhaps also of the methods of the Melanesian Mission. For it is probably the importance Christians have attached to the idea of the Church as the Body of Christ which made a Community rather than an individualist revival possible. And though concentration on the training of native teachers and the building up of a native priesthood rather than on mere surface evangelization is a method fraught with grave dangers’Äîrequiring great courage, an unconquerable faith in God's purpose for man, and a Christlike trust in man's possibilities’Äîand not one from which quick results are to be expected, it is becoming universally recognized that such is the vision of His Church which is nearest to the Heart of Christ, and that when the slow pain of growth is accomplished the harvest is rich indeed.

When the Brotherhood was started it was written, "Some day we dream of Households all through Melanesia, wherever heathen are still to be found; we dream of a Brotherhood centre, a House for each Household; a Church complete in the Beauty of Holiness; great gatherings for devotion, discussion, refreshment and renewal of vows. Somewhere in our dreams we seem to see white Brothers, too. No longer do we hear the cry, 'Send us more men,' for a greater Voice than ours has called and has been obeyed."

Even before ten years have passed, much of that dream has become reality; for the rest the future [23/24] must speak; the passage of time alone can show the extent of the movement's influence, its nature and its permanence. For us it is sufficient to recognize the hand of God in our midst, to rejoice in the great good that has already been wrought, and by our prayer, offerings and life, so to link ourselves with them that the work may not only be begun, but also continued and ended in God, and the men swept on to ends impossible to see in all their rich promise at the first, yet ever implicit when one man gives himself over absolutely to God's direction.

The Rule of the Brothers is simple and healthy, yet far-reaching, and provides great opportunities for expansion within the original framework. All is summed up in the motto they have chosen, "I am in the midst of you as he that serveth," and the first rule explains their aim: "The work of the Brothers is to declare the way of Jesus Christ among the heathen, not to minister to those who have already received the law." Each Brother takes for one year a vow of poverty, chastity, and obedience to the Elder Brother and to the Bishop who is the Father of all the Brothers. At the end of that period the vow may be renewed or not, but in the event of non-renewal the Father must first be notified.

The whole Brotherhood is organized in groups from four to eight Brothers forming a Household, supervised and directed by an Elder Brother, chosen by the members. Each Household meets four times a year for discussion both of the work and of any problems which may arise. The frank statement of opinions or grievances is encouraged, thus preventing the feeling of repressed dissatisfaction which is so often a [24/25] hindrance to any corporate undertaking. At the meeting, before any other business is discussed, the Elder Brother asks the rest, beginning with the junior member, "Brother, have you anything against any of the Brothers you wish to speak of?" Questions are asked or complaints aired; the Brother concerned replies, and the Household considers the matter. Lively discussion often results, but usually a settlement is reached. If this is impossible the matter is referred to the Father and his decision is final. No one is spared. An Elder Brother was once charged with inconsiderateness and general lack of care for his Household, and this resulted in a decision that the Elder Brother should ask the others if he had done anything to offend, and not wait for a complaint to be made. Finally, the Elder Brother himself tells of anything of which he has to complain. Each Household can make laws for itself, but these have to be approved by the Father before they become binding. A Brother may change his Household with the Father's permission, and the Father is also furnished with a yearly report of activities and progress.

Besides the quarterly meetings of each Household an Annual Chapter of the whole Brotherhood is held when vows are renewed or a Brother leaves, questions affecting the whole community are discussed and fresh plans made. It is only at such a Chapter, acting under the Presidency of the Father, that changes in the Rule may be made.

For the actual work of evangelism the Households are subdivided, the Brothers journeying two by two (by the Rule none may work alone). Two Brothers at least are always in residence at the Brotherhood [25/26] House at Tabalia. This was solemnly dedicated in 1928 in the presence of numbers of white men, native clergy, and boys from Maravovo, the ceremony being completed by dancing and a feast’Äî"and very great joy on that day." The House strengthens the educational efforts of the Church and also gives a sense of stability and settled life refreshing to the Brothers whose work keeps them for long stretches on the move. The other Brothers visit the villages of the district allotted to them, never staying in one place more than three consecutive months. Originally it was planned that at the end of that time they should submit a report and pass on, their responsibility ending when they had informed the Father and priest or missionary (if there were one) in charge of that district, of the village's willingness to welcome a teacher, though they must remain until they had seen that teacher provided. But it was quickly found that such teachers were not immediately forthcoming. In O Sala Ususur in 1927 it was written, "At the present time these four coast villages are waiting for permanent teachers. Some of the bush villages are prepared to receive teachers and before long others will be the same." And in private letters the stress is the same. "Do you all of you pray with warm hearts that God may inspire those fit to go forth to teach the people we Brothers have made ready." Therefore in 1927 it was decided that for the time at least certain Brothers must be allowed to settle in the districts they had opened up, and themselves to act as teachers, lest ground be lost. Their status in the Brotherhood would remain the same and they would continue to live according to its rules. In 1928 Ini mentioned that Brother Ben Pupulo had [26/27] returned to his home at Tambulivu for a time to take the place of a teacher "who is always ill, but he is still counted as one of the Brotherhood." As far as possible they are allowed to choose their own district, subject to a final ruling by the Father, and they have proved themselves willing to be used as he has judged best. John Pihavaka, the first of the Brothers to die in the cause, only expressed the spirit of most of them, when on being asked where he would like to work on his next trip, replied wherever the Father thought he was needed.

When there is a Missionary in their district the Brothers fit in with his plans, although they are not considered to be subject to his jurisdiction. The Brotherhood is meant to supplement, not to supplant, existing Church organization.

Such a Rule has proved itself adequate to meet the demands of the purpose for which it was planned. Under it the young men learn both initiative and obedience; self-control and with it a sense of responsibility. The village teachers have often failed to assert themselves at a time of crisis. Encouragement, practice in speaking out, in exercising their own judgment, side by side with continued respect for authority, have already had incalculable effect in building up strong characters, in producing men free because bound as Christ's servants, indifferent to the praise or blame of men.

The Rule emphasises that the "spirit of prayer is the secret of influence," and although on their journeyings the Brothers have to go months sometimes without the Sacraments, prayer is kept in the forefront of their lives and obligations. Nor is work other than [27/28] actual evangelism forgotten. The Brothers have always worked with their hands, and recently each Household has made itself responsible for a particular craft or industry in order to pay the Government tax levied on each man. Thus, while one Household builds canoes, another makes Church furniture; others do inlaying work, or make mats, ropes, fish-lines, or any other things for which there is a demand. One Household keeps pigs and another grows tobacco. From the beginning also the Rule left room for periods of refreshment for mind as well as body.

The provision for the renewal of vows has already proved itself a wise one. Plantations and Government services in the islands have been severely criticized for the part they play in aggravating the serious depopulation by absorbing young men just at the time when they should be beginning to take their places in the village economy. This was carefully guarded against in the Brotherhood. Marriage is only postponed, except in the case of those who feel that their work lies permanently with the Brotherhood, and the young man, who has been a Brother, matured by his experiences, takes back to a more settled life a richness and a strength which he can get in no other way. His own life and that of the village should benefit equally. The Brotherhood has shown itself to have room both for those called to a life of religion, and for those whose road leads to the equally exacting ways of domesticity, and Christian family life. Numbers of the Brothers have availed themselves of the short-term service.

If the examples of history may be used as forecasts of the effect certain conditions may be presumed to have, at the very beginning the positive character of [28/29] the Rule and its directness would seem to ensure a successful issue. The great days and exploits of western monasticism lay in the time before the Rule was so over-elaborated that to keep it a man was almost forced to lose sight of the purpose it enshrined; the greatest achievements of the Friars belong to the time when the Rule was almost entirely the "royal law of liberty," "perfect selfless love." The Rule framed at Siota in 1926 seems to have been in the direct succession of its historic predecessors.

Changes were, of course, inevitable; they have been effected with an ease and naturalness impossible under a rigid Rule. The development necessitated by the shortage of teachers has already been noted. In addition, in 1928, a school in connection with the Brotherhood was started at the Brothers' House at Tabalia. Ini wrote, "There are wanted here only fully adult young men who have put away childish things, and are not for ever chaffing and playing about, but are sufficiently staid and serious about the things which pertain to the knowledge of Christ the Saviour of us all." The school was intended, in fact, to meet the needs of those who were too old to go to one of the established Mission schools; it has also developed into the training house for future Brothers. The school is at present in charge of the first white Brother, Dr. Fox (Brother Charles), with five native Brothers. Its establishment marks an important change, for it means that no longer, as at first, are new Brothers recruited solely from among the School boys, but that the infection is spreading to the villages also. Those who have not had the advantage of a long Christian training are yet being so infused with the [29/30] true Christian spirit that they in turn wish to join the company of the followers of Him "who serveth." Brothers are now often men such as he of whom it was written, "He has not been to any of the larger schools in the other islands, but he has been sufficiently instructed about our Heavenly Father, Whom we preach, in his own country. In his heart he knows that he is able to help others who do not yet know God, which should put to shame many others, more learned, who do not want to help the ignorant."

Such men undergo a year's training as "Tinqoro," disciples, and then are admitted to full Brotherhood status.

Recently the Brothers have had to take further steps to meet the need for teachers, with the result that a school for boys from the bush villages on Central Mala has been started on an old Government site at Maka. A white priest, with the help of three Brothers, gives an intensive course of training there to boys who are to be sent out as teachers to hold the ground where the Brothers have penetrated until fully-qualified men are available.

All this was in the future when the first little band responded to Ini's call, but it is mentioned in passing to show the lines of development elasticity made possible. Much had to come first, and even in 1928 there was little idea of so rapid a growth. The Bishop then did not think that, for some years to come, the total number of the Brothers would be more than twenty, or that many new districts would be attempted. At present the Brotherhood has more than eighty members, and these are at work in the two schools, mentioned above, in districts on Guadalcanar [30/31] and Mala, on Sikaiana, Lord Howe Island, Opa, Raga, Rennell, in Fiji and New Britain and at Tulagi, while there is a dream that the future may hold out to the Brothers the task of carrying the Gospel to the tribes newly-discovered in the interior of New Guinea by Government explorers. The map will show the significance of this list. The story of such progress is to be numbered among the ever-recurring wonders of Church history.

[32] CHAPTER III PROGRESS. THE FIRST STAGE THE high hopes and boundless enthusiasm with which the Brothers set out were at once tested severely by the chill discouragement of almost complete failure. It must have seemed hard; probably for the ultimate success of the work it was better so. There is a danger in early success; it may or may not create spiritual pride, but it certainly tends to make man overestimate the part played by the human element. All disciples have to learn that their weakness is God's strength; that the thrill of realization that they have been chosen as His fellow-labourers has to die before God can speak through them; to learn, in fact, complete trust in and dependence on Him. It is not only the blaze of the fire that tests the sincerity of a man's purpose, but perhaps even more the cold darkness of failure, when the soul, impatient for visible results, is assailed with a feeling of desertion by Him to Whom it has offered itself. The Brothers faced this test and came out victorious; they might not at first overcome the heathen, but they conquered any desire to give up the fight. They have had to face perils and hardships and disappointments enough since, but never again has the indifference and opposition been so absolute as on this first occasion. Ini had been in touch previously with one or two villages in the interior of Guadalcanar, and had been promised a hearing. When the Brothers actually arrived, they found the situation changed. In one [32/33] place, where the inhabitants were described as living in dirty and careless conditions, the Chief refused to hear until the neighbouring villages had tried the new way. He seems to have been so anxious to get rid of these disturbing guests that he made a feast for them, killing a pig and offering them money to be given to the Bishop and Governor, "because he did not wish to receive the religion." The Brothers refused the money, as Moffatt said, "because he did not give it with good will," and continued their journey.

At the next place they were refused for a different reason. The Chief was willing, but the people were afraid of offending the ghosts, and there seems also to have been some dislike of a new teaching which it was thought might interfere with conditions of labour and so prevent their obtaining money for the Government tax. The Brothers were not ill-treated, but were politely shown that neither their presence nor their message was required. At the end of the first week they attended a feast, hoping thus to get into touch with the men from the scattered villages, who would come to this central meeting-place, but here also their message left no impression, and there seemed to be nothing left but a reluctant and rather weary return to Headquarters. Hope revived when it seemed that the first chief was going to make a final sacrifice of pigs to his god and receive two of the Brothers; again, however, it proved illusory. The people appealed to the District Officer, and he decreed that they were to be left alone. Disappointed, weary with their journeying and with the colder atmosphere they had encountered at the greater altitudes, they came back to Tambulivu . . . the adventure had failed.

[34] But the spirit in which the Brothers had set out was still strong, and while some of them remained at the House, ready to go out again, should more encouraging news come from the villages they had approached, Ini and a companion went to another part of Guadalcanar to talk things over with the Priest-in-charge and to sound the attitude of the people in this new area. Things proved distinctly more encouraging. Half a dozen or more villages were ready to receive them if the Bishop would give permission for a fresh sphere of work to be attempted. Thus while news at Headquarters was still negative (a further attempt on one of the early villages had resulted in the flight of all the inhabitants), the Brothers assembled at Vera-na-aso for their SS. Simon and Jude's Day Chapter, with the sense of failure lightened by their own still undaunted courage and the possibilities in the new district.

The Chapter was delayed until All Saints' Day, by the non-arrival of the Bishop; then it was agreed that, as they were willing to go on, it would be better to cut the first losses and start afresh in the more promising part of the island. The Southern Cross carried them to Aola and in that neighbourhood and round about Tasimboko the second attempt was made.

The original experiment had, however, not been valueless from the point of view of the Brothers themselves. They had learnt to work together as a team, and had seen something of the conditions which they must be prepared to face. Brooding over difficulties is not an asset to anyone, but a knowledge of facts is, for it at least prepares a man somewhat for those difficulties and enables him to face them with his [34/35] eyes open and his mind alert. Not least they had learnt that the only failure is refusal to go on.

At the end of 1927, the Bishop's report on the work in the diocese contained a significant sentence: "And the Brotherhood has gained a firm hold on Guadalcanar." Much lay behind the remark; disappointment, effort, hard work, skilful planning and courage; still more lay ahead.

Progress was perhaps not spectacular, but it was steady. On this second journey the Brothers were joined by another recruit, John Patteson Nana, and the eight then started work in four villages along the coast near Tasimboko. From there it was found that a considerable population could be reached by continual journeys, some short, some distant. The four villages welcomed them and "sought from them the way of Life." Some of the young men especially were anxious to build houses for them and a schoolhouse. Reception farther afield varied. Some places welcomed them, some were wavering and same, definitely refused, but the 1927 Chapter saw the Brothers full of hope for the future. Invitations had come from another part of the island, Marau Sound. Some new men had joined and there were promises from the boys at Pawa, and results had been such as to justify fresh work away from Guadalcanar altogether, on islands which have from the beginning proved specially difficult. At the end of 1927 Ini and Brother Basil Tavake set out for Santa Cruz.

[36] CHAPTER IV THE PRICE OF DISCIPLESHIP ONE of the most romantic books in the Bible, the Acts of the Apostles, has often been considered dull, a mere chronicle of names of places and of people, coming in a certain order, to be remembered for examination purposes and forgotten as soon afterwards as possible. The living portraits, painted in S. Luke's exquisite prose, the excitements, hardships, adventures of the way, told so simply and graphically, the miracles, which seem so completely expected and natural, have all too often been hidden from the imagination of youth, by guides who have insisted on chronology at the expense of life, on the dry bones of history at the expense of real personality.

Lest the romance, the adventure, the hazards and the wonder of this story of the acts of new apostles be hidden for a similar reason, it is proposed to show briefly, in the Brothers' own words where possible, some of the conditions they had to face, something of the price of discipleship.

The sketch of the background from which the movement sprang is meant to provide food for our historical imagination, but it is admittedly difficult for us in twentieth century England to realize just how much the Melanesian who joined the Brotherhood had to be prepared to pay. From us, Christianity demands sacrifices different in kind, if not in extent or spirit, from those required there. For most of us [36/37] travel, journeys to strange places, seem quite natural. We are used to leaving our familiar surroundings for long or short periods. There may be excitement or a sense of adventure still in so setting out, but fear of the unknown is largely diminished and there is not the same sense of cutting ourselves off from the familiar as there was even fifty years ago. Of course the conditions under which we travel are totally different from those which the Melanesian has to face; he has difficulties hard for us to understand, but even leaving those out of account for the time, there remains the more fundamental difficulty. To the Melanesian, travel is not a natural thing. There were, of course, friendly contacts between certain villages and certain islands, and the presence of the white man had made it seem less strange to leave home and to go among strangers. But pioneering evangelism was certainly not in a Melanesian's tradition, and in spite of the fact that he was a member of the British Empire, the way had not been prepared for him as it had in some measure been for the early missionaries of Europe by the cosmopolitanism of the Roman Empire. The Brothers have gone to places where men from their own part of the diocese have never been before; to men whose language they did not know and whose attitude might or might not be friendly. And as the customs and habits vary so considerably from island to island in spite of racial kinship, the Brothers must have met with much that seemed strange, besides a sense of loneliness, even apart from the spiritual loneliness which there must always be for Christians living in contact with those who have not known the same depth of spiritual experience.

[38] This setting out into the unknown has probably meant more to the Brothers than many other things which they have had to undergo; the inherited fears and suspicions of a whole people are not easily cast aside, and there is much unwritten heroism hidden under the bare facts of the places where work has been opened up. Men from the north went to the south, Solomon Islanders to New Guinea; Melanesians have gone to Polynesians, and further, they have gone even outside the diocese itself, for two went for three years to Fiji, to minister to Melanesians who had been taken there for plantation work. They were their own people, but many of them had been born in Fiji, and had never known or had forgotten their own island; their language was strange, and in addition, there was the bewilderment caused by streets and cars, things unknown to them at home; by unfamiliar food and by a knowledge and outlook far in advance of their own in many ways, yet divorced from that spiritual foundation on which all their own simple learning was based.

That is the price which their mind has had to pay toll has also been taken of their body. They have had to face S. Paul's perils by land and "perils by water." Their journeys have led them into untouched bush, along river beds which might suddenly be flooded owing to rain higher up in the hills. Shore men have penetrated the mountains, where they have suffered terribly from the cold. Two Brothers, Paul and Joshua, crossed over the island of Mala in the most difficult place, to districts considered unsafe by the District Officer, and Joshua died from illness contracted from exposure on the journey. But they found [38/39] the old men, hostile though they themselves were, beginning to realize how potent was this new life. "We are like fish in a net," said one did chief, and another "Christianity is like an epidemic; there is no escape from it." As a result of this journey invitations have come from these interior villages.

The Brothers have always had the difficulty of penetrating unknown bush without a guide, and the possibility that food might not be forthcoming, whether from hostility on the part of the inhabitants or sheer necessity in the district. Daniel Sade wrote, "We are first building Houses and making gardens at Takataka, and then when that is done we shall journey out into the bush villages. Some of them are hard to find. Four of us tried to begin the work in February, but could not get very far as no one would lead us to the villages. They asked us for tobacco and money, but we do not have these things, and so they refused to direct us. No one offered us food; we had nothing to eat during the four days we were out. The journey back to our centre was very weary; we were discouraged and faint for want of food, but we shall set out again."

Even when the site of the village is known there is always the possibility that the people may not actually be living there. The Government of the Solomons insists on a permanent village being made, but the people often prefer to live on their various garden sites in temporary houses. To get in touch with such people, the Priest-in-charge of the district has to be prepared for a similar nomadic existence, adding overwhelming difficulties to his already strenuous work, and it is obvious that, even for the Brothers whose [39/40] work it is, difficulties of missionary work are intensified when they have to pursue the inhabitants to their various resting places, arriving perhaps to find the village deserted, and the inhabitants again on the move. Moffatt foreshadowed this when writing of the events of the first trip.

"We went up to the higher land; we slept one night on the road, then came to the village; but it was not the real village, only a place for working the gardens and feeding the pigs."

The Brothers never know when they may be called to lay down their lives for their faith. Suspicion of strangers is ingrained in the heathen bushmen, and the Brothers have not even the protection his colour, and fear of Government reprisals in the event of an attack, would give to a white man. The first journey showed indifference and point-blank refusal to listen; there has also been open hostility.

Two Brothers entered a village up in the hills and told their story. The chief listened, kept them for the night, and in the morning brought them out to hear their fate. They were told that in obedience to his spirits they must die. But, while he was speaking, the chief started back, putting his hand to his eyes. "There were two Brothers came in last night," he said, "two Brothers were brought out this morning; but now I see three Brothers. Is your Spirit so strong that He is able to be with you like that?" The Brothers' lives were spared, and they were able to tell more of this Great Spirit, but they had walked very far into the valley of the shadow of death.

Borne up as they are by their unconquerable hope, radiant faith and the visible signs of success which [40/41] they have been given, they cannot fail sometimes to know the feeling S. Paul knew when he wrote, "Only Luke is with me." They are cut off from the Church's means of grace for long stretches of time; there is no outsider present doing similar work with whom they can talk, and in spite of the growing numbers it must seem sometimes that they are all too few for the task. Besides, the cry is still for teachers to carry on and consolidate. Probably it is in part this sense of isolation that prompts their earnest demands for the prayers of others, that through them they may, in such moments of weakness, feel the certain communion of the whole Body of the Church.

Brother Daniel was only echoing many others when he concluded the letter quoted above, "Will you pray that God the Holy Spirit may guide the head-man at Takataka that he may see the true way and become one with us? We need your help in this way for our work."

[42] CHAPTER V THE BROTHERS AT WORK WITHOUT attempting to give a detailed account of the work of the Brothers in each district, something of the remarkable progress of the movement since the earlier struggles were overcome can be seen by following their methods of attack, which, allowing for variations caused by local conditions, are everywhere very similar.

When the Brothers enter a new district, a headquarters and some provision for their stay are the first necessities, and accordingly a house is built and gardens are made.

"At present we are busy planting yams and can't do much else yet. Pray that our yam harvest may be a good one."

This comes from Takataka where the Brothers had found it useless to rely on supplies from the bush villages they visited, and had also seen how the work was hindered when their vitality was lowered by lack of food.

The procedure adopted depends on the number of Brothers available. If they are few they concentrate on the village, gathering hearers round their house and proclaiming the message to them; if more men are available, some go to the villages further afield, working from the common centre.

A school house is built as soon as possible and [42/43] regular instruction given. Brother Ini gives a detailed account of early activity on Sikaiana, a small island inhabited by Polynesians, who up to the time of the Brothers' mission had been untouched by the Church. The school for adults had originally been the chief consideration, but it was found that this had led the people to regard prayer lightly and to overestimate the value of the more purely secular learning. Therefore the Brothers realized that in future greater prominence must be given to prayer. From the island comes the picture of men and women gathering for Matins and Evensong in the court-house, until the Church should be built. Until they knew the Offices and their meaning, the Reader first said the General Confession, the Lord's Prayer and the Apostles' Creed, the people repeating them after him till they knew them by heart. When Ini wrote, they had not attempted singing’Äî"It is hard to get their voices in tune, they will wander away from the right notes."

Gradually other parts of the Liturgy were added’Äîthe Litany, to be said on Wednesdays and Fridays, and the Te Deum on Sundays before the Lesson.

Thus the infinite teachings contained in the Liturgy of Christendom continue their age-long work of instruction through worship, supplemented by the Brothers' words and by their lives, for in the same report Ini adds, "In visiting the sick we sometimes read the prayers, and always I have prayed silently, remembering the nature of the illness and the nature of the person."

Instruction continues until the great day comes when the first baptisms may be held.

At the same time schools both for adults and for [43/44] the children are held. Again, writing of Sikaiana, Ini said, "The children's school is very nice. They all come together to prayers every morning and evening, and for school each morning and afternoon, and have singing and learning by heart such things as the Psalms, Magnificat, Nunc Dimittis and the Litany, in fact whatever they need to know in the services." In addition, pupils in various stages learn the elements of arithmetic, reading and physical drill. Promising pupils from all districts are sent to the Central Schools or to the Brothers' Headquarters at Tabalia, and when an island becomes Christian, the Brothers sometimes help the Mission press to prepare a prayer book for their people's use.

It is essential to realize that, while the Brothers are thus engaged in constructive work, there is a destructive element of evil warring against them. While in some places the difficulty is one of inertia, on Sikaiana, where the people are stronger physically and mentally, it took the form of organized opposition. The Brothers were handicapped by the prevalent indulgence in an intoxicating drink made from fermented coconut sap, which deprived a man of all sense of decency and reason. Catechumens were asked to give it up, but while the habit was so strong all round them it was not easy to prevent their falling away, and the Brothers were sometimes in danger of attacks by men under its influence.

"This thing is really bad," wrote Daniel. "On June 25th, in the night, one man who was tipsy with that drink took a spear and was looking for Brother Ini to spear him with it. But he did not see him for he was already asleep. Oh, he went backwards and [44/45] forwards on the path, and blew a conch and spoke evil of us and of the Mission. Our people were angry, but I said, 'Never mind, don't be angry; we should not be angry or afraid of things like that.'"

One of the Brothers gives a vivid picture, reminiscent of Elijah on Carmel, of great heathen meetings to pray for the rain which might break up the Christian festivals of Christmas and Easter. No rain fell. "One of them who made the spells said to me that his spirit had told him that he had tried to get the rain-clouds, but had not been strong enough, that God was so very great."

Similar news came from Santa Cruz and from Mala. The isolation of the Santa Cruz group, linguistic difficulties, climatic condition and a people with an unstable reputation, gave to this district its peculiar problems. Yet it is a part with a particular claim on the Church. Her servants have gone there to their death, dying in agony from the tetanus that succeeded a wound from the long Santa Cruz arrows, feeling nothing but pity and love for the people who had caused their sufferings. And Bishop Patteson, who was himself martyred on a small island in the group, seems to have had an even greater longing for these people than for any others. Almost the last clear picture we have of him is his gazing over the islands off which the Southern Cross lay becalmed. Then he went ashore to his death.

Work was opened up, native and white teachers and priests battled with the difficulties; a few schools were started and men and women were baptized and confirmed, but the shortage of workers and lack of adequate transport prevented a regular campaign [45/46]

there, and in 1928 Santa Cruz and its neighbouring islands were still largely heathen. Even the boys taken from there to the Central Schools had been less reliable in every way than those from other parts.The difficulties of the Brothers were not less than those of their predecessors, but they had the advantage of having in Brother Basil one who understood the people and the language, and their reception was good. They were able to make a start with evangelistic and teaching work, and when Ini went to Guadalcanar for the 1928 Chapter, it was with the knowledge that a Church and school house in a suitable village awaited the seven Brothers whom the Chapter appointed for further efforts there. Yet once more the place took its toll. One Brother contracted an illness and died in hospital later, and the progress of the work was not swift. Only through constant contemplation of the Christ was discouragement kept at bay. "We know that till now Satan is warring against Christ. The measureless sufferings of Christ upon the Holy Cross must be borne in mind by those who are called to labour in Santa Cruz, for the name means 'Holy Cross.'"

An example of the reality of the struggle against spiritual wickedness in high places is given in the picture of the Brothers going to the house of the spirits and driving them out. "And on that same evening the owner of the house, a man named Mebuna, came to prayers. And with great joy we praised our Heavenly Father for this."

The island of Mala, too, had always been a serious problem, and one for which a solution was urgent in view of the fact that the island contained forty-five [46/47] per cent of the population of the Solomons. Conditions of life were exceedingly primitive, and attempts at betterment for long seemed hopeless. A catechist beginning his work was greeted by the remains of a cannibal feast, the head of the victim hanging from a tree. It was a problem of wild people, who spoke so many different languages that an observer who heard them at certain Christmas services was reminded of the day of Pentecost; a problem intensified by places difficult of access,’Äîone impossible to solve without more man-power. To the very place where the fight with heathenism seemed desperate came the Brothers, and the work which they have been able to do gives grounds for hope in other stubborn localities.

On North Mala "the people of Maana ere got a house ready for the Brothers to live in, and began to plant a yam garden to provide them with food." Here they were installed with prayers. "The Bishop had previously informed the people of North Mala that the Brothers were coming to live among them, and there was much fear and confusion in their hearts and minds in consequence. But why were they afraid of the Brothers? Was it because the Mala people were wild and were murderers and cannibals? It was because of the power of the Holy Ghost, for He is able to save whether by love or by fear."

The writer of these words followed them up with an appeal for help in the task: "Are there any who will come to help the Holy Spirit save those who lie bound in the shadow of death, and are in fear of the darkness of the power of Satan and his angels? Let no one say he is not worthy. We Brothers are not worthy for our part; we are wounded in the fight; [47/48] we fall in the war, but we get up again and stand upright; and we are not afraid nor do we retire, but fight on."

The Brothers also try to raise the standard of life among the people whom they visit, and to inculcate a different social outlook. They give whatever medical help they can, and the presence of one of them made a great difference to the morale of the Leper Colony to which he was attached for a time. On Sikaiana the great number of those preparing for Baptism was noted, and also, equally significant, their beautifully clean skins and freedom from sores. Better methods of cultivation are demonstrated, and one Household on Raga, in the New Hebrides, has established a plantation where natives may see how the gardens in their own villages may be improved by more regular and considered work.

In addition to such direct attacks on completely heathen districts, the Brothers have helped to strengthen Church life among people nominally Christian, who had become indifferent and self-satisfied. In various parts of Guadalcanar in particular they have been reawakening enthusiasm and holding missions in co-operation with the native priests already in charge, and, as has been said, they have gone to their own people overseas in Fiji.

There was much that was unsatisfactory in the condition of this Melanesian community, stranded in an alien land as a result of early recruiting of native labour for plantations, and its proper supervision by the Church in Melanesia was difficult. Regular Church services were held at Suva, and a school was carried on there for the children, but little could be [48/49] done for those of them who lived scattered about in the distant villages. It was doubtful at first whether the two Brothers who went to help these people would succeed amidst their strange surroundings and problems, but gradually they settled down, and in 1931 a visitor from Melanesia found each of them in charge of a class in school and superintending the boarders in the Hostel at night. "Besides helping in the School and Hostel, they take part in services on Sundays and each in turn goes out to a village doing mission work. This part of their work interests them very much, and no doubt when they know more of the language they will be given more of it to do."

So well did the work go that, when the two years for which they had volunteered had expired, they were asked, and consented, to stay another year. When they left, passengers on the Southern Cross, so soon to be a wreck, it was with the consciousness of a piece of work well and truly done.

Moreover, they took back with them Malachi, a young Fijian of Solomon Island parentage, who wished to join the fellowship and to return, after training, to minister to the still pressing needs of his own people. This was an important result; "He who does the work is not so productively engaged as he who multiplies the doers" (John Mott); and, as elsewhere, the Melanesians in Fiji needed more leaders to help them in the Christian life.

But Malachi was not to be permitted to do more than answer the call; his service may have been fulfilled in his willingness to go. He died at Pawa in 1933 before his training was completed.

Similar work is being done among the work boys [49/50] in the Solomon Islands at government and commercial centres, and in a mission to those at work near Rabaul in the Mandated Territory. Land for a Church on Tulagi was granted by the Resident Commissioner, and the Mission Press printed a small English Prayer Book written by the Brothers in simplified English for use both there and also on the plantations, where English of a kind is the usual language.

This Church is becoming the centre for the men who form the crews of ships, for those in government service, for the hospital orderlies and for others who have been caught up by the needs of the white man and by advancing civilization. The work is important and may be far-reaching. These boys come from islands which are still heathen. Until this venture of the Brothers they have been cut off from the ordinary channels through which the Church has worked. Now, their period of service done, they will go back to their islands as confirmed members of the Church, perhaps to be the new evangelists there. In the early days of Christianity, the Church grew, not only through the efforts of those whose names have been handed down through the centuries, but also through those who went away as soldiers or traders, and in the midst of their business found the "pearl of great price."

The multiplicity of languages is a difficulty everywhere in Melanesia, and so the Brothers have made great use of dramatic representation to convey the message. For a long time the Schools have produced Nativity Plays. The Brothers, under the inspiration and direction of Ini, have attempted even more ambitious things. The following are extracts taken from the account written by one of the Brothers of the [50/51] story of Holy Week as worked out by Brother Ini from the Scriptures and acted on Mala.