|

BY BEATTIE, HOBART COMMITTEE FOR THE MELANESIAN MISSION |

|

THE BOYS LOUNGE ABOUT THEIR "NAT-IMAS" WHEN YOU ENTER, YOU WILL THINK IT BEAUTIFUL NOW COMES "FALL IN" FOR THE BOYS THE BOYS . . . COME HOME FROM THEIR WORK EACH WITH HER BUNDLE OF FAGGOTS |

PAGE 25 39 43 53 |

WHO likes holidays? I suppose there's only one answer to that question. Every Saturday is nice, but the going-away kind of holiday is the best of all, don't you think?

Well, I have a suggestion. Suppose you all come with me for a short holiday to Norfolk Island! It is really one of the prettiest spots in the whole world, full of different kinds of scenery. And you can go bathing, and fishing, and mountain-climbing, and shooting, and riding; you can play golf, and football, and cricket, and tennis all the year round (if you've nothing better to do!); it's never too hot, and it's never too cold, and ----

But isn't Norfolk Island a long way off? asks some very wise person, who knows a great deal of geography.

Yes, that's true! I'm afraid it is rather far away. If you live in England, you must travel about 13,000 miles. If you live in Australia, you will have at least 850 miles to go. Those in New Zealand are a trifle nearer, but even they have a voyage of 600 miles before them! You see, unfortunately (between ourselves, we sometimes say fortunately), in Norfolk Island we are really 600 miles from anywhere; we haven't even any neighbouring islands--unless you count Phillip, and only rabbits live there. No, we are only an insignifi-[9/10]cant little full-stop in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Then what's the good of inviting us to go there? grumbles somebody.

Listen! I know a quicker way of traveling than by P. & O. or express train, quicker than motor-car or airship. A way by which I have myself travelled to the North Pole, and to Fairyland; back into the days of Richard I., and to all sorts of odd times and places. Yes, you've guessed it! You only have to get between the covers of a book, and the cost of the fare is--Imagination! Have you got it ready? Then let's start.

On the way (it won't take long, and I promise you shan't be sea-sick) I will tell you why I have chosen Norfolk Island for our holiday-trip. It begins with a sort of confession.

When I was at school, somehow or other there was one kind of book and one kind of magazine which in my ignorance I always looked upon as dry. And that was--anything about missionary work! Now of course I am speaking of many years ago, and of a very foolish child. Things are different now, I am glad to say, in these days of "King's Messengers" and "Sowers' Bands." And I hope that no boys or girls dislike geography as much as I used to. But still it has occurred to me that there may yet be a few who think that "Missionary" means "very dull."

You see I have found out myself that missionary work is the happiest, and most interesting and worth-doing work in all the world, so naturally I want, if I possibly can, to open the eyes of some who don't think very much of it at present. And one always has a feeling when out there that if only one could transport the people at home into the heart of things, and let them spend even a few days with us, they would all be just as interested and keen in the work of the Melanesian Mission as we workers are ourselves.

[11] There, how honest I am! I have let you find out my secret already, and I must trust you not to turn back home in a hurry, because you know now what I am driving at, as well as where we are driving to!

Are you fond of history? Oh, don't shudder! I'm not going to put much in here. But you can't land at Norfolk Island without having the least idea who are at school here, and how they came to be.

If you look at the map you will see what a number of islands are scattered over the South Pacific Ocean, far away from any of the continents. Can you find five groups, called respectively the Solomon Islands, Santa Cruz, Torres Islands, Banks' Islands, and New Hebrides? If so, you have put you finger on the main part of the Diocese of Melanesia. Our Mission is hard at work among the natives of these, and a few solitary islands, such as Tikopia and Vanikolo. Many of them are cannibals, some few are head-hunters, and nearly all those who are still heathen spend a large part of their time in fighting and killing. I have had the pleasure of calling upon them at home, and some day I would like to tell you stories of the islands, but not now.

I wonder whether you have heard the name of John Coleridge Patteson. To Eton boys it is familiar, for he was one of themselves. And his name is often on our lips, for he was the first Bishop of Melanesia, and we love and honour his memory. After being ten years Bishop, he was killed by the people he went to help, in 1871. The next Bishop was John Selwyn, whose memory we also prize. His father was the first Bishop of New Zealand, and the founder of the Melanesian Mission in the year 1849. (No, I know you don't like dates, but there are three important ones that I must put in.) Our present Bishop is Cecil Wilson, the Cambridge athlete and Kent cricketer of the 'eighties, who was consecrated in 1894. So much for history and dates!

Now Norfolk Island is not actually in Melanesia, [11/12] but it has such a beautiful, healthy climate that it has been chosen for the headquarters of the Diocese, and for the College of S. Barnabas. S. Barnabas is our training-ground, or manufactory, as one might say, for native teachers. It is filled with boys from thirty or forty different islands, who are brought here in our own ship, the Southern Cross, and at last taken back to teach their brothers and sisters the Good News they have learnt in Norfolk Island.

How would you like to live on an island measuring less than six miles by four? Small as it is, it always seems large enough both for ourselves and our friends the "Norfolkers." These latter folk are mostly descended from the mutineers of the Bounty, English sailors who married Polynesian women of Tahiti at the close of the eighteenth century. The Norfolkers have their own church and school unconnected with our Mission, but they are the kindest of neighbours, and we help one another whenever we can.

Now look up and see Norfolk Island in front of you.

After six days' tossing, or more, on a rough sea (for the passage from Sydney is one of the worst to be met with) this little green spot of land, away by itself in the middle of the ocean, is a most refreshing and lovely sight. And the nearer we draw, the lovelier it appears, with its woods and hills, streams and fields. A real mountain rises on one side, and the rocky coast is defended by cliffs, two hundred feet high in many parts. There is no harbour, and in the winter it is sometimes impossible for boats to get to land. But though winter brings high winds and heavy rains at times, it seldom [12/13] means cold weather, and frost and snow are unknown.

We have anchored on an early morning in September--about where winter ends and summer begins. That sounds funny to English ears, but you know things are topsy-turvy on the other side of the world, and as it is day here when it is night over in England, so also it is summer with us when it is winter in the old country.

When I first came out, an old village gardener heard about this, and it was explained that when they were all going to bed, we should be getting up and beginning our day's work. He looked puzzled, and said, "Eh, but it'll take some time to get used to it, won't it, turnin' night into day like that!" But twentieth-century boys and girls are wiser. It does seem odd, though, to have no autumn and no spring.

Can you smell the land? There was a shower at dawn, and the fragrant, moist land-breeze is wafted across to us. A faint blue mist is floating over the masses of gigantic pine-trees that make one of the special beauties of the island. See, some have even straggled over the edge of the precipice, to win a difficult root-hold down the cliff's side, and come within the splash of the white surf.

Now the first whale-boat is put off from the shore. In a few minutes a handsome, swarthy, bare-footed Norfolker, in shabby clothes, and a home-plaited straw hat in his hand, is bowing before us with the grace and dignity of a Spanish nobleman, and in a soft quaint drawl he bids the strangers "We-elcome to No-orfolk I-island!" We shake hands, and very soon afterwards, when the whale-boat has been crammed from stem to stern with boxes and packing-cases of all sorts, you find a somewhat rickety perch atop a huge case of stores marked "M.M.", and so are rowed to land, feeling rather like the figure on the triumphal car in a circus procession.

[14] The process of landing is not too easy, for these green rocks are as slippery as ice, and unless you are ready to jump at the moment the word comes, the opportunity is past, and a leap would be into the sea, instead of on to the land. But don't look around at the boiling surf. All you need is enough faith to yield yourself into the strong hands ready to receive you, and lift you into safety.

See, we have a pony-trap from the Mission waiting for you to step into it; for though S. Barnabas is full three miles from this landing-place, the whistle of the steamer reached listening ears long ago. Don't think it was your own coming that was so eagerly awaited by everybody! There was something more important than yourself beside you in the whale-boat, namely the mail-bag. No one knows the value of letters until one has, like us, to wait a month between each post.

I see you looking curiously around as we begin our drive between gaunt grey stone buildings that seem wholly out of keeping in this sunny island. How big and grim and cold they are! And look! here on our left are ruined walls, and traces of more ugly, forbidding buildings. They are ugly and forbidding indeed, for these are the remains of the Convict Station that was established here more than a hundred years ago, when the worst and most dangerous criminals, who had just escaped hanging, were transported to this, of all spots on earth, that they might be safe out of the way of other men.

This was a desert island when discovered by Captain Cook, and its first inhabitants were these poor wretches who, having sinned grievously, were in their turn grievously sinned against by unjust and stony-hearted officials, who knew that they, as well as their prisoners, were out of the way of inquiry and oversight. By chains, and whips, and guns (you may see some of the hideous relics to this day), the prisoners were kept in most bitter slavery; and one lovely spot bears the name of "Bloody Bridge," [14/15] in memory of a fierce revolt in the 'thirties, when the miserable convicts rose as one man against their oppressors, and many on both sides were here killed in desperate conflict.

In the cemetery yonder, that lies amid the driven sand of the sea-shore, may be seen the graves of soldiers and prisoners side by side, some with curt, ironical inscriptions, such as, "Pray for the soul of Michael Murphy, late of Dublin, who died suddenly on the 3rd October, 1830. He was hanged." And to this day mysterious gun-shots and cries are said to be heard of a night in that great, low, gloomy house, now the residence of the Chief Magistrate of the Island, and formerly of the Governor of the Prison.

All the convicts were removed fifty-three years ago, and I am glad there are none left. But about a year after their departure, a strange sort of canvas boat was found in the heart of the bush, that some poor fellow must have been making in secret, with a wild hope of escape.

This part of the island is called Kingston, or shortly, "Town," though it is the queerest town surely that was ever dignified by such a name,--with no street, no lamp, no shop, no inn, not even a policeman, or a postman, or a milkman!

But we are now winding up a long, steep hill, with a banana valley below us on the right, where great white arum lilies glisten among the green, and to the left an upland pasture dotted with cows.

What are those trees over there laden with yellow fruit? Why, lemons, to be sure, wild lemons! They grow here in their hundreds and thousands, and may be picked at will. We clean our floors and tables with them. There are plenty of delicious oranges, too, and pineapples, peaches and figs in their season, but these do not grow wild. Other pleasant fruits do, however, which you have probably never tasted, such as the guava and loquat. So fertile is the soil that they say, "Plant a walking-[15/16]stick, and you will see it grow! but I don't know of any one who has tried.

And those nice little yellow apples, growing on the thorny plants that cover the ground,--what are they called? May one pick and eat them? I should not advise you to. I cannot tell you the plant's real name, but the one we all know it by is expressive enough,--Poison! You remember the warning from Alice in Wonderland--"If you eat much of a thing marked 'Poison,' it is almost certain to disagree with you sooner or later."

Yes, this is the worst of our field-enemies; its roots are so strong, and it is so hard to destroy. There is nothing for it but burning down and digging out. When, however, it really is killed, the soil upon which it has grown is said to be peculiarly rich, and that thought is a comfort when fighting the foe. Do you know, I think there is a kind of parable wrapped round our nice-looking enemy the Poison, but I shall leave you to unfold it for yourselves. You won't see much of that weed on the Mission lands, I hope. The story goes that an officer's wife in the convict days brought the first root of Poison as a rare and pretty plant for her garden. Little did she dream what a curse she was introducing into the island. I should be sorry to say how many roods of good ground are lying waste to-day under Poison.

You will not notice many roadside flowers. For one thing, our fields are bounded by wire fences instead of hedges. There are some familiar-looking members of the dandelion family--for the rest, this pretty yellow acacia and the bright crimson salvia are by far the commonest. For daisies and buttercups, primroses and bluebells, you may hunt in vain.

I think I hear you give a sudden cry of surprise and delight, as I did myself, when a pair of gorgeous parrots, with cardinal-red bodies, and heads, wings, and tails of a dazzling blue, fly screaming after one another before our face. Yes, indeed, we have [16/17] many birds to boast of: gaudy parroquets, all green and blue and red, which haunt the olive trees; kingfishers numberless; doves whose feathers are shot with bronze and green; dainty fan-tail flycatchers, who pirouette in the air, and have so little fear of human beings that they have often been known to come and perch on an outstretched finger.

Then there are the little vivid green thieves we nickname "white-eyes," because of the white rim that gives them such an impudent expression. These come and devour the fruit even while one is picking it. Other birds there are which are called robins and sparrows by the Norfolkers, but I'm afraid they would hardly recognize their homely namesakes of the mother country, so gay of hue are these robins, so flashy and trim these big sparrows! Oh, and there are many other charming little feathered folk whose names I don't know. But I must freely own that, with all their beauty, they lack voices. The low twitters and loud cries of our birds are a poor exchange for the songs of the lark and nightingale, the thrush and blackbird, of dear England. The butterflies are very large and handsome, but not of so many different kinds as one might have expected.

At last we have reached the top of the hill, and Peter, the old grey pony, breaks into a trot as we turn into the famous Avenue of Pines, that leads straight to S. Barnabas. Look at the grand old giants, towering skywards! Did you ever before see a pine to be compared with these? Some are said to attain two hundred feet in height. Small wonder that the Norfolk Island Pine has become celebrated! But, somehow, the sixpenny pot-plants thus advertized in England seem rather a long way behind these their great-grandfathers. This avenue, which is a mile long, was planted by the convicts nearly a century ago, so you see the trees have had a few years to grow in!

Notice this small damsel, eight years old perhaps, who meets us with a smile as she canters fearlessly [17/18] along, all alone, on a big rough-paced horse, a great bunch of bananas in her arms, her wee fingers just able to grasp the bit of string that serves for reins, her bare legs too sort to reach the dangling stirrup. You may see such a sight any day, for the Norfolkers learn to ride almost as soon as to walk, and they are more at home in the saddle than on foot. Horses here are cheap, they want neither stables nor grooms, nor are they ever shod. These red roads are soft, you see, and not metalled, so the horses canter feely along them, as if on turf. And best of all, they need fear no motor, wait for no train, snort at no steam-roller. Here the country is as it was in the Middle Ages!

We are nearing the Mission-station. The fields and cows you now see are Mission property, and the wooden houses standing in the neat gardens we are passing on the left are the homes of some of our missionaries. They are all bungalows--I mean, there is no up-stairs in a Norfolk Island house. That's rather nice, isn't it?

What's that funny sort of round tower on the right? You're no farmer, or you would know that it was a silo. We're rather proud of it, because we haven't had it very long. Inside we store our green crops in such a way that they make fodder for the cattle when grass is scarce.

Now I should think you are rather tired, so wel'll make a pause. You can rest till I call you again.

One! Two! Three! Four! Five! Six! Clang, clang, clang, clang, clang, clang!

Wake up, you people! I hope you heard the Vanua clock strike six, followed by the clanging of the Vanua bell. That means, "Get up--get up--sharp--or you won't--be ready--in time!" It's easy [18/19] enough to rise at six in summer, but in winter when it's dark the bell needs to sound masterful.

What and where is the Vanua? some one asks, rubbing sleepy eyes. (Make the "u" in it like "oo," please) I must answer by a further explanation. When I showed you that Melanesia was not the name of one country or island, but of many, I did not go on to tell you of one big difficulty in consequence of this, which our Mission has to face. I mean the curious fact that every island, no matter how small, speaks a language of its own. Indeed, the larger islands have two or three languages a-piece, so those living on one side cannot always understand their opposite neighbours. In the old days, when the two sides were hardly ever at peace, this didn't matter so much. But how are boys and girls speaking, say, thirty different languages to be taught in one school?

Bishop Patteson cracked this hard nut for us long ago. He chose the speech of one of the little Banks' Islands, called Mota (which had given him more pupils than the others), to be the universal language of S. Barnabas. Certainly his choice was Divinely guided, for forty odd years of experience of island dialects have led every one to see the wisdom of what looked like a rather haphazard selection. Mota is perhaps the fullest, and yet the most easily learnt, of all.

So our conversation, whether in work-time, meal-time, or play-time, is in Mota; our prayers and hymns, our school-teaching, everything is in Mota; and whether the children brought to us come from north or south, it is surprising how quickly they pick up the foreign tongue. All the ocean languages are cousins to one another, so Mota comes far more easily to Melanesians than to Europeans, and we often envy our scholars in this respect. Among themselves, the boys or girls of one island naturally chum together and talk their mother-tongue, but we like them to use Mota a rule, that [19/20] they may become thoroughly at home with the language in which they must here be taught the Good News of God, of His love and of His laws. I say "here," because the missionary work in the islands is carried on as far as possible in the speech of the people, and parts of the Bible and Prayer-book are translated into very many of the Ocean tongues.

Now Vanua is a Mota word, and it means the place where people live. It is sometimes used of a whole island, sometimes of a village, sometimes of only a small cluster of houses. It is in this last sense that we use the word in S. Barnabas, and we only include the group of buildings on one side of the road, where the boys live with the unmarried white men. The Vanua contains six houses, of which four are semi-detached, and in each a white "father" has charge of a family of boys, varying in number from twenty to thirty, according to the supply of "fathers," and the number of boys in residence at the time. You will also find in the Vanua the Chapel, the big hall, the kitchens and out-houses, the Mission shop or "store," as we call it, the printing-house, and the carpenters' shop. The girls live--some seven or ten in a family--among the married people and the single women-missionaries on the opposite side of the road.

Hark! A trampling of horses' feet on the grass! Come on to the verandah, and you will see perhaps a score of strong horses being driven from their pasture to the horse-yard, where those required for the day's work on the farm will be separated from the rest. Behind them follow two or three merry boys. These are the first Melanesians you have seen, so look at them well. You may remark that they drive their bunch of horses with more caution than courage, but I would plead that, until coming to Norfolk Island, these fellows have never seen any animal bigger than a pig!

The first thing I want to point out to you is that they are not black by any means, although some [20/21] one long ago must have though them so, or they would not have got a name that means "black" (Greek, melas). We are for ever trying to explain to our friends that Melanesians are not negroes. Their colour and general appearance vary much according to the district they hail from. By slow degrees one come to know the Northerners (i. e. those from the Solomon Islands) from the Southerners (i. e. the Banks' and New Hebrides people). The Santa Cruzians again are of a distinct type.

Now I will call one of these boys, and you shall see him close to.

"Samuel! Mule mia iake! (Come here)."

Up he runs, smiling and showing his nice white teeth. Samuel is a Gela boy (Solomon Islands), and a little darker than some. The skin of many is a light clear brown, just the tint of a sunburnt gipsy. Others, like this Samuel, are rather of the hue of a cigar, and you very soon come to admire the colour, which is so suited to its sunny surroundings. Really we whites look somewhat sickly and washed-out by contrast.

The hair again varies greatly. A few have short hair like an English boy's, with only a wave in it. With some the colour is light--a reddish, or even a golden-brown. But most, like the boy before you, whether from the north or south, rejoice in these raven-black, fuzzy, curly mops that I delight to see. They stick out from three to six inches from the head, making a hat quite unnecessary.

I think the Melanesian eyes are almost always beautiful--dark yet brilliant, and often fringed by long curling lashes. The noses are well-shaped, not flattened like a negro's, though they have wide nostrils and full lips. As with ourselves, so with the Melanesians, some are short of stature and clumsy in appearance. But the great majority are well-proportioned and extremely graceful, with shapely limbs.

Samuel is still a young lad, perhaps sixteen or [21/22] seventeen years of age, but I want to draw your attention to the expression of his face. His Christianity seems as it were to shine out. No one could ask, "Is that boy baptized yet?" Gela is an island in which there are few heathen left, and Samuel is the son of Christian parents. For a wonder his ears are not pierced, but two rows of blue and white beads ornament his neck.

Every Melanesian has a natural taste for decoration, but the form it takes varies among the different islands. Tattooing is not so universal, or as a rule so elaborate, as among the Maoris, but in its way it is very common among both sexes. Two lines on a cheek, or just a circle with rays, or a leaf-spray, may often be seen, and on the arms and legs scrolly patterns are carefully worked out. But the favourite device is the frigate-bird, or the sign that stands for it, but which you would rather guess was meant for a sprawling M or a W. The girls have a foolish custom of tattooing the names of their special chums on their arms and hands, spoiling the pretty smooth skin, as we tell them in vain. Besides, they change their particular friends as often as English school-girls do, but there can be no changing of the skin!

The lobe of the ear is nearly always pierced, and sometimes such great heavy rings have been hung from it that it hurts one to look at the hole. I have often seen a poor ear so stretched that a boy could thrust his fist through the hole, from which hangs a thing like a napkin-ring. The Northerners are fond of wearing a cluster of bone rings, the size of a sixpence, in one or both ears. To this they will add anything that comes handy, such as the wheels from an old watch. Even a safety-pin will serve on occasion as an ear-ornament. In the Banks' Islands sticks are more popular than rings. These are made of bamboo, and are about as long as an ordinary pen-holder. The bamboo is peeled, then a delicate pattern is scratched upon it with a [22/23] sharp stone or a pen-knife, and finally it is smoked over a fire till this is fixed.

Nose-rings are rarely seen in S. Barnabas, I am glad to say, though they are universally worn in some islands. When they do appear here, they are so small you would hardly notice them. Necklaces are much fancied on both sides; indeed, if a girl is seen without one, it is a pretty sure sign that she is in trouble about something. The ornaments are always removed as a token of grief. And I have known a boy to exchange a present of a knife for some beads. Blue beads are the favourite kind, but gilt ones and paste-pearls are not uncommon. Bracelets, too, are very general. These will be either of plaited grass died red, of shell, or of curved boars' tusks. If anklets appear, they mark newcomers, and the commonest kind are the bands of red plaited grass. As these break and perish they will not be renewed, for somehow or other they are not according to the lingai, or Melanesian custom at S. Barnabas.

How do you like the way we clothe our scholars? There is no attempt at a uniform. You saw Samuel had blue dungaree trousers and a light shirt. Of course there is woolen beneath, and in winter we give them flannel shirts and nice warm, dark coats. The feet, like the head and hands, are always bare. You will see all the girls in short yoke-frocks, of many colours.

Did you hear a shout of "Bell"? It is given by one of the white men, and in response the chapel bell immediately begins to ring. A boy was standing under the little bell-turret, rope in hand, ready for the signal.

Come with me to Matins! At sound of the bell, [23/24] every house sees its occupants turn out, and set their faces in the same direction. All the world of S. Barnabas gathers together in God's House every morning and evening at seven o'clock. On Monday, Tuesday and Saturday mornings Matins is said; on Wednesday and Friday the Litany; and on Sunday and Thursday, and every Holy Day, the Eucharist is celebrated.

How clean and bright our scholars look, freshly washed and combed, and happy in the prospect of a new day! As the girls pass though the Vanua gates, all chatter and laughter ceases; quiet and serious, they approach the porch. If a stream of boys is already passing in, the girls wait, and the boys do the same in their turn. They would never dream of entering side by side.

I wonder if you have already seen a picture of our chapel. Whether or not, I am quite sure that when you enter you will think it is beautiful. It is a small building, but it is famous on this side of the world as a gem of its kind. Outside one admires the hewn stone, but within you notice how large a part these dark-brown timbers play in the structure. The roof is an open one, and the supporting posts run down to the ground like shafts all around.

The east end is rounded, or apsidal in form, and it is lighted by five small stained windows, designed by the great artist, Sir Edward Burne-Jones. They picture our Lord in the midst of the four Gospel-writers. Christ is painted as the Almighty King, with one hand raised in blessing, the other holding the orb. Each Evangelist is accompanied by his symbol, and at St. Matthew's feet bags of yellow gold have fallen, and are spilling their treasure unheeded.

The seats are ranged down the sides to face one another, as in English colleges. Look how beautifully the bench-ends are inlaid with mother-of-pearl and tortoise-shell, in all sorts of devices and emblems, the loving work of missionaries' hands.

[26] A large font of coloured Devonshire marble stands close to the west door. Oh, I do wish you could have seen that font on Easter Eve, when ten lads stood around it in snowy-white shirts, with their chosen witnesses beside them. Fearlessly confessing the Faith of Christ crucified, and renouncing the Prince of Darkness in whose dominion they were born, they were then and there baptized with water into the Name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, and made inheritors of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Polished black and while marble paves the broad aisle leading to the sanctuary, which is naturally the most beautiful portion of the chapel, with its coloured marble floor, and glittering mosaic reredos screened with richly-carved wood. Gold and green hangings cover the wall on either hand, and our silken banner--crimson, and gold and white--rests against the other side. Unseen beneath the altar lies a casket containing the grass-woven mat in which Bishop Patteson's body was wrapped by the natives after they killed him, at Nukapu in the Reef Islands. Our martyr's grave is the deep sea, but this simple mat is precious to us. The green altar-frontal is finely embroidered, and glitters by candle-light as if with jewels. Above it you see in the centre a massive silver cross that has been made out of Bishop Patteson's own table-silver, and this is flanked by silver candlesticks and vases of flowers.

The chapel itself stands as a memorial to Bishop Patteson, and none of its ornaments has been provided out of the general funds of the Mission. All are the special offerings of friends and worshippers. And the visible glory of God's House is an object-lesson to our Melanesians, who so keenly appreciate beauty and brightness. They see that there may be both an outward and an inward "Beauty of Holiness," and that man should offer unto God in worship that which costs him something. So in their distant islands hereafter they will strive by patient handiwork and reverent care to make their own little [26/27] churches as clean and fair as they can, that they may seem to speak to the heathen and the careless around of the joy, and loveliness, and order of true Christian worship.

We have a far larger number of boys at Norfolk Island than girls, and they occupy two-thirds of the space in chapel, the western block of seats being reserved for the girls and the white ladies. Any white laymen there may be sit [sic] among the boys, but the clergy who are not officiating sit in the stalls facing east, just within the door.

On entering chapel each boy and girl kneels in silent prayer, and their reverent conduct throughout is remarked upon by every stranger who visits us. Such an irreverent posture for prayer as sitting and crouching forward is unknown at S. Barnabas, and would amaze a Melanesian. What makes them so reverent? It is just their faith. They believe God is really present.

The Melanesians have no set religion of their own, no gods or temples; and when they accept the New Teaching (as Christianity is called), they do so unquestioningly, in that spirit of trustful childhood that our Lord so loved to see.

Matins begins with a hymn, and you must not be surprised to see some of the new scholars unable to find the number, for the Mota figuring is rather a long-winded business. What the priest gives out this morning, for instance, is this: "O as [the hymn] melnol vatuwale o avaviu sangavul rua o numei tavelima [125!]."

The organ is a fine little instrument, presented by the late Miss Charlotte Yonge, who wrote the stories your mothers and fathers used to enjoy. It is always played by a Melanesian, and played surprisingly well too. A couple of boys stand beside him to help with the stops, and the lead the singing. When one organist's course of training is ended, and he goes back to the Islands, there is a little anxiety as to who will succeed him; and perhaps for [27/28] a few days we may have to sing unaccompanied, to the precenting of a white man; but within a week, Mr. Bailey, our blacksmith and master of music (N.B.--We call him "The Harmonious Blacksmith"), pronounces that one or two more are ready for the post, and all goes smoothly again.

How they sing! Don't you wish the congregation at home sang as heartily? The girls are shy, and don't sing out as we should like them to, but the boys give no cause for complaint in that respect. The Mota prayers will sound strange in your ears, but the chants will perhaps be familiar, and you can remember that the meaning of the words is the same as in the English Prayer-book. One of the head-boys comes forward to read the Lesson. The surplice and cassock look a little curious at first, with a necklace and a fuzzy head above, and bare brown feet below, but one soon comes to feel it is just as it should be.

Matins only lasts some twenty minutes. There is a pause for silent prayer after the Grace; then we stand while the priest and reader pass into the vestry, and wait thus till we hear their prayer is ended. Then the boys sit till the girls have filed out seat by seat. As we go, lift your eyes to the glowing rose window at the west. Below it is a row of small stained lights, in the middle of which you will see S. Philip baptizing the Ethiopian eunuch.

Breakfast comes next, and for that we all make our way to the dining-hall.

It is plain and bare, but down each side hang portraits of those who have gone from us, whose memories are dear to the Mission. The latest addition to these is a likeness of the Rev. C. C. Godden, [28/29] who was murdered by a native in Opa, October 1906.

As you enter, you see a long table on your left, a still longer one running down the centre of the hall, and a number of short tables placed at right angles on the opposite side. The first table is where the girls all sit together, the middle table is for the white missionaries and any native head teachers who may be staying at Norfolk Island. The boys sit at the short tables in sets of about a dozen each.

Whatever are those big roots piled high on plates before every boy's and girl's place? Those are steamed kumaras, or sweet potatoes. They taste rather like boiled chestnuts, and our Melanesians eat them by the ton. In fact, they form the chief food in S. Barnabas. On some mornings boiled rice is provided, on others kumara. But for dinner, kumaras always, though meat is added on Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday. With their tea they have bread or biscuit.

Now all have taken their places, and the Bishop knocks upon the table as a signal to stand for grace. Then all set to in earnest. You see some boys acting as waiters among their fellows. They have laid the tables, and as the plates are emptied, they collect them and carry them off to the kitchen that leads out of the hall. Their breakfast-time will follow ours.

These boys are called the cooks (or kuks, as we usually spell it) for the week, and their work lies in the kitchen instead of the fields. Next week they will have other duties. Each of those sets now sitting at the tables will become kuks in their turn. The cook-week (kuk-wik) is looked upon as of great importance, and for his part in it each boy receives a small payment. On account of this, the sets of boys into which the College is divided up are called kuk-sets. Whenever our ship, the Southern Cross, sets out or returns, there has to be a fresh arrangement of kuk-sets.

[30] About a dozen of the best of the elder boys are chosen by the authorities as moe-kuks [head-kuks]. These then each choose another good senior boy to be his piring-kuk, or mate. Both these positions are looked up to, and no doubt coveted, by the rest of the boys. They carry with them certain privileges, but on the other hand much is expected of these monitors, and they learn to be exceedingly careful both how they speak, and act, and use their influence. A sudden outburst of temper (and Melanesian tempers are fiery), a defiant retort--and a head-kuk may find himself put out of office, and a junior, but more reliable, lad set over his head--for a time at any rate. But to be downgraded even for a time is a rare and severe punishment, felt most acutely by those who undergo it. They are chosen so carefully in the first instance, that it is only boys whose sell-control and obedience have been proved by years of training who have any chance of promotion to the rank of head-kuk.

When the kuk liwoa [first and second kuks] have been chosen, they make up their sets by selection from the rank and file. The boys all stand together at one end of the hall, and join their sets as their names are called. This is the moment that reveals publicly a boy's character--which are the lazy or stupid, unwilling or sullen ones. Oh, yes, there are some of all sorts among the Melanesians, just as among white folk!

You may see a big, shamefaced boy, perhaps, trying to shelter himself behind the little chaps. They are being called before him, for he has shown himself slack and careless this last term, and the head-kuks want none such. Left to the last, he gloomily joins the twelfth kuk-set--because they had no choice left! Poor fellow, he is not to be envied to-day; but it is surprising how much good the lesson often works. If he is sensible, he takes it to heart, and makes up his mind it shall not be repeated, but sets himself to win a different name by steady, willing work.

[31] Hall meals do not last long. The brown folk consume their soft food very quickly, and the whites learn to follow suit. So we make our way out-of-doors again.

It is now a quarter to eight, and on both sides of the road there is sweeping and bed-making to be done, and repetition to be conned over before the Vanua bell announces school at a quarter-past eight. There is a song our scholars sing to the old air of "Buy a broom!" which has reference to the early morning at S. Barnabas. Translated, it runs thus--

"Sweep the house, you fellows! The bell will ring directly.

Run--run--run--run! or you'll have to stand up!

There's the bell! It's a school, you fellows! Let's go at once!

Whoever comes late will soon be standing out.

Perhaps it's already written up, "Stand!" for it is late.

Woe be to us if we arrive late!

Don't dawdle, you! It is the Bishop's rule,

'Every late-comer shall stand!'"This they sing in Mota with great gusto.

School is not in a separate building at S. Barnabas, but in every house there is a large room where the different classes are taught. Then the big hall is used for the principal boys' school-room, and on the girls' side there is a nice airy sewing-room where the first class generally assembles. In the hot weather you will sometimes find classes on the verandah.

From a quarter-past eight until nine Scripture is taught throughout the school, and passages from the Gospels or Psalms are repeated by heart. When the clock strikes the classes change. From nine till a quarter to ten other subjects occupy them--reading, arithmetic, or English.

What class she we go and watch? I fancy the girls will amuse you; they are so anxious to learn, and so afraid of making mistakes. We have given up teaching English to our girls, because they do not as a rule stay long enough with us to make much progress, and it is of little use to them in after life.

[32] Here is a class of younger children busy over figures. They do not know much yet, and they are very shy of saying what they do know. One has to get used to the slow, timid Melanesian girl's manner in school, and endless patience is needful. If you write a sum on the black-board, there are sure to be some murmured exclamations, to the effect that they can't do it, don't know how, etc., even if it is a simple rule that they have been doing for weeks. Then they are very, very slow in accomplishing it, and they seem to need to rest their brains, after writing each figure, by a long stare round. When they have finished, they reluctantly allow you to see the sum, and each assures you with great emphasis that she has "gone astray entirely," or "it is completely bad!" I find those who protest the most are generally correct--and they know it! Of course one is not now talking of those who have been some years at Norfolk Island, and have grown more sensible, but the ways of new-comers.

Yes, even with slates they are shy enough, but when, as with mental questions, they have to use their mouths entirely, it is still more embarrassing. Hands go up to heads, and shield their faces or cover their mouths, till ordered down by the teacher.

"Now listen, girls! I have twenty cocoanuts, and I gave Mabel two; how many have I left?"

"Twenty-two!" says a small eager voice; and the whole class agrees with her!

When the mistake is pointed out, the poor little speaker is covered with confusion. She smacks her forehead, as though anxious to return the stupid answer whence it came, and should she make a second blunder, it will quite possibly drive her head under the table, to appear again a moment later if we take no notice.

For the boys English is an important subject, for we want them to understand what they or their friends are agreeing to when they come in contact with traders or planters. The seniors get on to [32/33] translating Æsop's Fables, and can generally understand more than they can speak. English is a hard language to the Ocean peoples, because their nouns have no plural endings, their adjectives no degrees of comparison, their pronouns no genders, their verbs no moods and tenses.

What a blessing for them! you say. Yes, but then they have no end of queer and fidgety distinctions, which they look for in English. One instance of what I mean will be enough for you, but you must remember that there are plenty more that could be quoted.

Let us take the English pronoun, We.

If I am teaching some boys, and say to Walter, "We read this yesterday" (meaning, "You and I"), I use the word Nara. But if I turn to Henry, and say, "We have read this" (meaning, "Walter and I have read it"). I use Kara. If, however, we three have all read it, and I am speaking to them only, I say Natol, and if I am telling the rest of the class that this is so, Katol represents the "We." But suppose all the class has also read it with me, and I am reminding them of the fact, I must say Inina or Nina, whilst if only I and some others who are not present have read it, the "We" to be used is Ikamam or Kamam.

The pronouns "You" and "They" are divided up in the same way, and if one makes use of the wrong word, it is regarded as a good joke to be handed on. So you may gather that that the Mota language has its little difficulties.

The Melanesians have a clear sense of fairness and unfairness, and they understand perfectly that they must neither help themselves by copying from a neighbour's slate, nor help another by prompting [33/34] in a lesson. But they are by nature very kindhearted one towards another, and therefore they find it exceedingly difficult not to help in every way they can.

I am tempted to say a little more about a few points of character that most Melanesians have in common. I should like you to know them, not merely from the outside, but a little from the inside too. A very little only, because for one thing, they are just as different from one another as you and I, and also, because we are always finding out ourselves how short a way our own knowledge goes in any case.

In his heathen state the average Melanesian is lazy, unclean, quarrelsome, pitiless, and treacherous. Yet he is by no means destitute of what one of our early Celtic missionaries saw in us long ages ago, and called "Natural goodness." The primary virtue of the Melanesian is generosity. He is ready to give liberally of what he possesses, and to share whatever he receives. He is the soul of hospitality: unless there is reason for suspicion, every stranger is treated as an honoured guest. And stinginess is to the islanders the one unpardonable sin. You may be blood-thirsty; may have for an unpleasant hobby the collecting of human heads; such little weaknesses must be borne with: but if you are mean, if, when you return from your head-hunting, you refuse to give me the arms and legs, then you are wicked and depraved indeed, and must be killed at the first opportunity, and eaten with the greater relish!

Seriously, in itself this spirit of generosity seems to me a beautiful thing, and one often feels that in this respect the Melanesian is on a higher plane than the average European. But its practical results are rather curious. For example, the love of competition has no existence in the natural Melanesian. He or she will gladly hand over any number of marks to a friend, or go slowly in a race, so that [34/35] no one may be left behind. It would certainly make the work of teaching easier if one could put a little more of the competition spirit into them.

In a certain island-school the Bishop once promised prizes to all who should be present at a stated number of times in the year, in order to encourage regular attendance. When he next visited them, he therefore consulted the register, and distributed rewards to those who had earned them. To his disappointment, however, instead of giving the pleasure he purposed by doing so, the whole school-people, teachers and prize-winners included, put on a sullen and unfriendly air. What was the matter? Why, they were disgusted to find that their Bishop was a stingy man, who singled out a few for his gifts, instead of treating all equally! There were no more prizes given in that vanua!

Here, too, when Christmas comes round, the system invented in the Wonderland "Caucus-race" is employed: "All have won, and all must have prizes!" If I give a child, who happens to be standing by, two or three biscuits from the bottom of a tin, I can be pretty sure they will be carefully divided, and handed round to every friend within hail, as a gift from me! At meals in hall one not uncommonly sees boys transfer a spoonful of rice or lump of kumara from their own plates to their neighbours'. In chapel none would ever dream of putting less than silver in the bag; in fact, there is quite a contempt for coppers--"dark pennies," as the children call them.

But side by side with their striking generosity exists a deep-rooted selfishness. They will give everything but trouble in another's behalf. If one of them is ill for a day, he will have pity and kindness from all. But should the illness continue--be it that of parent or child, husband or wife--the friends soon tire of and neglect the patient, and when death occurs, it is apt to be hailed as a release--for the survivors! Heathen parents often kill their [35/36] young children, or get them killed, simply to escape the trouble of looking after them.

Stealing is quickly recognized as a serious sin, because it is the exact opposite of the great virtue--giving. But I think it is a little difficult for Melanesians, even when Christians of long standing, to put the fifth, sixth, and seventh commandments quite on the same level as the eighth. Instances of dishonesty have been known in the school, but they are rare, and as a general rule we are able to trust our Melanesians utterly. I think you will be amused to see how very openly and unguardedly we live in S. Barnabas. You will find doors and windows open day and night, whether we are at home or not. Drawers and boxes are seldom locked, and the Melanesian inmates of the house walk whither they will, yet are never intrusive, never in the way. They are such shy folk that, if we did not give them the freedom of our homes, and trust them as we expect them to trust us, we should never win their confidence, or break through the mysterious barrier that stands by nature between the heart of the brown man and the heart of the white.

I remember, as a new-comer, being rather startled one day when I was in the kitchen, and looking up, saw a big brown fellow stalking silently in my direction, through the sitting-room adjoining, hugging a loaf he had brought me. Another time I was writing by the window, when a fuzzy mop was stuck through the casement, and a soft voice inquired, "Ko we maros o horse qarig?" [Do you want your horse today?] The bare feet make the Melanesians such startlingly silent visitors. On this second occasion I know I sprang out of my seat with a little shriek, to the unbounded amazement of my swarthy friend. But I think now I am surprise-proof--ready for a caller in any spot, at any time!

It is a quarter to ten, and the bell has rung again, telling that school is over. You think our lesson-hours are very short. So they are, but they are quite long enough for Melanesians, who cannot do much hard thinking at any time. If they did lessons from nine to twelve, and two to four o'clock, like Europeans, they would soon be laid low with brain-fever.

Now comes "fall-in" for the boys. The words of civilization which cannot be put into Mota, we keep in English. See the boys come running from their different classes to stand in their kuk-sets, one behind another, the head-kuks in front. The drill is very short--just an action or two, ending with a united clap of hands.

Then they receive their instructions for the morning's labour. These two sets are to mend one portion of the main road; this one is to plant kumaras on a certain field; those are to weed a patch of onions, and so forth. The necessary tools are dealt out--hoes, spades, etc.--and off they go gaily, a white man accompanying each band, not to drive them as a slave-master, but to work with them. Listen to their fun and banter as they hurry along, their songs and shouts! The men say the more noise they make in the field, the better they are working; it is a sign of their keenness and energy.

They are such a merry race, these Melanesians--for ever laughing and light of heart. No, not always, though! They are too proud, too sensitive, and too affectionate to be always happy. Tears have a way of coming when one does not expect them, and you find that a chance word, spoken in jest or in haste, has hurt a tender heart, or wounded some one's pride.

We will not go with the boys to the fields. There [37/38] are days when the girls also are summoned to pick kumara tops or to weed. And it is hard, hot, dirty work, I can assure you. We go at it with a will, but are glad when it ends; and we pick lemons, and wash our black hands in the juice all the way home, making the scratches speak out!

However, to-day we shall find the girls assembled in the sewing-room, or sitting on the wide verandah, where they sew busily and silently until half-past twelve. Perhaps you wonder what we can find for them to do, for it is true that a very large number of clothes are made for our boys and girls by working-parties and guilds, at home and in the colonies. But when you have from 150 to 200 boys in residence, wearing and tearing clothes all the time, they require all the needlework that our girls' fingers can supply.

When breakfast ends on a Wednesday, the Bishop, or whoever is at the head of the table, says, "O qong wonowono, ragai! [Mending day, boys!]" and there is a joyous response of "We wia! [It is good!]" Each boy flies for his torn garments, which have been washed in readiness, and a procession of ragged clothes and their owners proceeds at once to the sewing-room, where the former are taken into hospital--to be exchanged if worn past repair. Every boy has a number which is worked on all his garments, so it is easy to check and arrange them.

Fortunately the girls one and all are fond of sewing, and tire less of it than of any other employment. They look happy and proud as they sit stitching away. We should like to be able to send them out oftener to work in the fields, as they will have to do nearly every day when they go home. But it is also important that they should know how to make their own and their husbands' clothes. One must remember that these girls, even the small children, are already betrothed to boys who we hope will become missionary-teachers; so we try to teach [38/40] them, not only what will be useful to themselves, but what they can show to others when they become teachers' wives.

Now come away to the Hospital! You see it is quite near--the long, red-roofed house at the end of this field, near the gate. Isn't it nice having grass to walk on everywhere, instead of hard pavement or gritty paths? On first coming, when people find there is no shoemaker on the island, they ask, "What shall we do when our shoes want soleing?" But the answer is cheering: "They won't want soleing! Grass doesn't wear out the soles." It is true. But the uppers go. The damp rots the leather, and shoes don't last long. There are two old-fashioned things most necessary at S. Barnabas--lanterns and galoshes!

A bright little garden smiles in front of the Hospital, and on the broad verandah there are hammock-chairs where the patients can lie, and read and smoke when they are well enough. The lady-missionary in charge of the Hospital is standing outside, talking to Lonsdale and Stephen, two consumptive lads, who are being kept as far as possible in the open air. It is hard to make them understand the reason for their treatment, and when their nurse's back is turned, they have a wicked way of sneaking inside the ward, where there is more fun and company than on the verandah. And when found and scolded, they look up with bright smiles and a "We wia!" and trot meekly outside again, no more convinced than they were.

This is the way, through the doctor's room, into the big ward. How sunny and cheerful it looks, with the pictures on the wall, and the games and puzzles about! But I seem to see it was it was, when we all had to turn hospital nurses, in 1906. Midnight; a dim lamp burning, and ten beds filled with sufferers from the epidemic, of which any case might take a serous turn, and end fatally. It was a very solemn and sad time, such as one could never [40/41] forget, for Death claimed ten of our Melanesians within four months.

There is a very pathetic side to the work in this Mission. The Melanesian peoples, who are singularly strong of muscle, and run about with weights which a railway-porter would think no joke, are in constitution as weak as water. Mild diseases, such as mumps and measles, are apt to assume fatal forms amongst them, and they die "like flies." The island populations have been decreasing at an alarming rate, owing to various causes. Consumption is fearfully common, and here at S. Barnabas, directly we see a boy or girl beginning to look thin and walk slowly, our hearts sink within us, knowing it is all too likely that the doctor's examination will reveal the presence of lung-disease, and we shall see them grow weaker day by day, in spite of every effort to save their lives. Then the one question is: Will they live till the ship comes back, and can take them to their homes, that they may die among their own people?

In a few of the stronger Christian islands the New Teaching and influence seem to have stemmed the tide; common-sense treatment of ailments is replacing the charms of the magicians, and the numbers are at least stationery--in some parts slowly rising. The Bishop has said, "We are placed by God in His infirmary." It is our hope and prayer that, by Divine Grace, we may find that at all events a branch of this vast "Infirmary" of Melanesia has become as it were a "Convalescent Home," though the influence of Christianity on the lives of the people.

Two or three of the cases just now are only surgical, and you see three merry lads are playing dominoes together. Reuben, this handsome, intelligent fellow, is from Ulawa, and you will gather at a glace that he is "bossing the show," as the Americans say. He is scolding loudly (his eyes dancing with mirth the while) the small youth on [41/42] his left for playing two dominoes at a time, while the latter, an unbaptized boy who has only recently come, and knows very little Mota, is laughing up at him with frank admiration, though he has not the slightest idea what has caused this delightful outburst. The third player is John, a big, steady, good-natured fellow who is also smiling at Rueben's nonsense. He came to us unbaptized, having been found, in fault of a better teacher, doing his best to lead the heathen children of his island (Vanikolo) to the Light, of which he had seen some gleams. Now he has been baptized, and is receiving fuller instruction, to prepare him to take his place on our staff of 800 Christian teachers.

A chuckle of laughter comes from the opposite bed, where a very little chap, called Warumu, from Ugi, is sitting up to see the fun. He has been in hospital for many months, suffering from dreadful sores all over his poor little body. Sometimes he gets low-spirited, and cries by the hour together; but on the whole he is patent and cheery, and makes himself remarkably useful. He can knit scarves, too, and sew a patchwork quilt.

Warumu is sadly jealous of his tiny neighbour in the next bed, which is surrounded by screens. Mewa is one of the smallest boys in the school, and when he was brought up last November, it was said we should have to open a nursery! But he comes from Santa Cruz, one of the most backward and disappointing parts of the Diocese, where we cannot at present choose our scholars, but must be glad to take such boys as they entrust to us.

One wonders that any mother could find it in her heart to part with Mewa. His poor ears have been so pulled and tortured out of shape, that he has got the name of "Poodle." But his wee face is lighted by lustrous, speaking eyes, and when he smiles no one could resist him. His patience, courage, and obedience are an example to the whole Hospital, and we felt that here was the making of [42/44] a young Christian whole future usefulness might be very great. He has picked up Mota, too, wonderfully quickly, and is sharp in every way. He is recovering nicely now from a severe attack of pneumonia; but, alas, the doctor has already discovered the first signs of disease in his lungs, and it would not do to allow him to stay here. He must return to Santa Cruz; but he may live some years in his native air, and we trust he will still be spared to do something towards helping forward the work of God.

We must leave the Hospital now, for I want you just to come and look into the printing-shop, where most of the translated Bibles, Prayer-books, etc., of the Diocese are printed and bound, as well as all the Mota literature that is used here. The missionaries help in distributing the type, and some of the boys get very expert and neat in binding; but the presiding genius is Mr. Menges, a semi-German, who is the essence of fun and good-humour, and can turn his hand to anything. He has worked in the Mission about a quarter of a century, and had a very adventurous life before that, of which he is never tired of relating yarns.

The bell again! Ah, that is a welcome sound, the Bell tuwale, or first bell, in preparation for dinner. The air seems full of mirth. The girls are pouring out of the sewing-room in twos and threes, hand in hand. And the boys from various quarters come whooping and singing home from their work. During the next quarter of an hour there will be much washing and splashing, and a little combing and preening before scraps of looking-glass.

The when the second bell has rung, we shall see them flocking into hall; boys with sunflowers stuck about their hair, or big red hibiscus blossoms, or plumes of grass, or long waving feathers--all wearing their decorations without a suspicion of self-consciousness. And some who have nothing else to put in, carry their combs in their hair. These are [44/45] in shape something like a capital "Y," and of course they stick the teeth downwards, and the long stem appears, with perhaps some beads or a bit of string hanging at the end of it.

As I have said before, every native loves decoration and gaudy colours. On Sundays it is the pride of the kuks to adorn the clean table-cloths with monstrous bunches of flowers, and when hall is decorated, as on festal occasions, the Melanesian ingenuity has its opportunity, and we see glowing and marvelous results.

I think dinner-time is a good stopping-place, don't you?

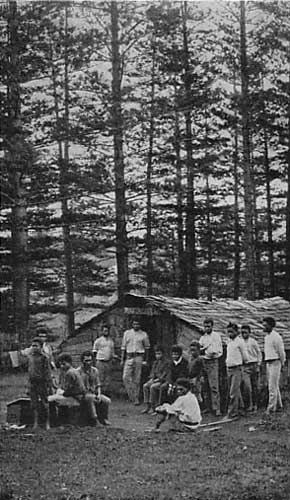

Dinner is over! We have only one course, and are often out again in less than fifteen minutes. But there is rest for every one until two o'clock. We whites often go to one another's houses for half-an-hour's chat over cups of tea. The girls play about in the gardens, or do what they like. The boys lounge about their nat-imas, and those who have attained the privilege of smoking do so.

In many of their own islands every man, woman and child is accustomed to smoke, and an infant on its mother's back will be given a pipe to keep it quiet. We are trying to influence the people gradually against this custom, and it is amusing to see how eager the men are to enforce a law against women's smoking! I fear it is not for the same reason as we would discourage it; but you see, if only they can stop it, there will be so much more tobacco for themselves!

A missionary was rather dismayed the other day at getting a letter from a too-zealous teacher, lamenting the frequent breaking of "the law of God which forbids women to smoke"!! He went on to say he [45/46] had beaten several of them for doing so, but they were very obstinate!

Did you notice a strange word I used just now, nati-ima? Mota again! Ima means a house, and a nat-ima is the "son of a house," just as nat-kurut is a puppy, and a nat-toa a chicken. What are these young houses?

In every island village there is a sort of clubhouse for men only, where they gather together to smoke and chat in the daytime, and sleep at night. So in S. Barnabas the boys of each group of islands are allowed to build such a place for themselves--a long, low shed, with a little opening at one end where they go in and out. There is no chimney, but that is no drawback in the eyes of a native. They make a blazing-fire, and enjoy all the heat--not to mention the smoke! Nothing is lost.

The nat-imas are rather exclusive places, and an interchange of visits between, say, the New Hebrideans and the Solomon Islanders, is rare. Just now there is such a large contingent from the Banks' Islands that the Mota and Motalava boys have built a nat-ima for themselves, and built it very neatly too. If they might, the boys would often spend the night over the fire in the nat-ima, but this is most unhealthy, and therefore forbidden. The white "fathers" sometimes have to go hunting round the little houses, to drive out some sleepy, reluctant youths who know they have no business there after the last bell has rung.

One! Two! The clock is followed quickly by that untiring bell, and white people and brown all go scurrying about to their various classes. From two to three there is writing-school. Shall we visit those nice, shy little girls again?

This class is a big one, and includes pupils in very different stages. Five or six of the children are writing from dictation the Apostles' Creed in Mota, slowly and neatly. They have just finished the clause, "Maker of heaven and earth."

[47] "Now for a new line! Wa i Jesus Christ [and in Jesus Christ]. A big W for 'wa,' mind! Why is that?"

We want, of course, the answer, "Because it comes 'at the back of' [after] a full-stop." But no one remembers that reason.

"Because 'wa' is a heavy [important] word!"

No, that guess won't do. "Wa" is a particularly light word, and the little girl smacks her forehead reprovingly. A very small maiden lifts up a beaming face.

"Because it stands so near to Jesus Christ!" she says.

We explain our meaning, and turn to the next group. Here they are copying from the blackboard all sorts of pretty names written in round hand, "Albert, Bertha, Charles, Dora," etc. This teaches them capitals as well as small letters. And oh, how hard they are trying! An occasional groan, or "Eke! Nau me ava ran!" makes known that some one has gone below the line or missed a letter.

About half of the scholars are sitting on forms at the table, and half on the floor round the room, with their backs against the wall. These are chiefly the beginners--married women, some with babies in their arms, who make writing of any kind rather a feat; others are tinies, only a degree bigger than the babies in arms,--dear mites who grasp the pencil solemnly, and labour for ten minutes, making the most appalling squeaks on the slate, before they will leave the first stroke alone. This third division is still at the pot-hook and hanger stage, but it won't stay there long. The Melanesians take readily to writing, as to needlework, or indeed to anything that hands can do, if it does not call for hard thinking; and you would be surprised how soon they learn to write their own names. And how proud they are when they get so far!

Three of the clock rings out our liberty. The [47/48] boys of S. Barnabas are keen on football, and it goes on till cricket is brought in by the advent of the Southern Cross. We have one of the loveliest fields, I should think, in the world, to play in, with views of sea and woodland (or bush, as we call it this side of the world), mountain and valley.

Here they come pell-mell in their red, shirts, racing and hallooing, to the Valis we Poa, or "Big Grass," which is the name of our grand old meadow, dotted with pines, and lemons, and white-oaks, and stretching right away to the cliff.

Association is our game, and the bare feet manage to kick right vigorously, you will see. Rugby would be too exciting and dangerous for our young men. As I have told you, Melanesian blood is very hot and easily roused. There is a dormant volcano inside every boy, which the most trivial accident might arouse in a moment,--and then, woe be to the offender! The savagery of a thousand years is not extinguished in a generation, and we have to avoid, as far as we can, doing anything likely to excite the old passions of heathen days.

The boys have the keenest possible sense of fair-play: they accept the referee's decisions without murmuring, and obey the rules. But if anything causes them to suspect an unfair act, they are furious, and capable (in what may be really righteous indignation) of doing violence.

House-matches are very popular, when no outside team is available; or those who are going down in the ship will challenge those who are staying up. A thing we never venture to do is to pit the northern and southern islanders against one another. There is a strange, deep-rooted suspicion and enmity between the groups, probably of centuries' standing; and the reflection of it is too often visible even among the Christian lads at Norfolk Island. Our aim, therefore, in school, and games, and kuk-sets, and everything else, is to mix up North and South together,--to merge in friendly effort, shoulder to [48/49] shoulder, the hostile feeling which is born in the natives of the two divisions of our Diocese.

In many, many cases it has already been splendidly overcome. Some warm friendships exist between northerners and southerners. A large number of southerners have volunteered for missionary work among some of the fiercest peoples of the torrid, fever-haunted North. But the majority on both sides, though quite good and peaceful as a rule, need but a tiny spark to kindle afresh the ancestral feud. A word of gossip spoken by a silly girl, or the jesting taunt of a mischief-loving boy,--and clubs, spears, arrows spring out from unexpected quarters, and there will be a bad half-hour for the Head of the Vanua, who will need not only courage and self-control, but tact and presence of mind, to avert blood-shed.

One has seen the old animosity awakened by a complaint that the rice was not well cooked, when the northern boys happened to be kuks, and the complainant was a southern girl, whose casual observation was maliciously repeated. S. James's remarks on the tongue in the third chapter of his epistle come home with fresh force in a place like this.

Of course, an outbreak of hostility is always severely dealt with. And it is one of the most hopeful signs of the influence of Christianity here that, as soon as a boy's temper has had time to cool down, he is ready meekly to accept and perform whatever punishment is meted out, and his penitence and shame are sometimes most touching to witness.

Not many months ago a big Santa Cruzian, who in a rage had seized a club, and was so violent that it took five of his fellows to restrain him, was so repentant when he came to himself that he not only took his sentence with a "We wia!" but a week or two later, after a little talk with the Archdeacon, he stood up before the whole school, and said bravely, "Brothers, I have done very wrong indeed, and my heart is sorrowful about it!"

[50] I wonder how many English fellows would have done that. I can assure you it costs a Melanesian not less, but more, than a white man, to own that he has done wrong--for he is intensely proud.

This is too bad of me. I have talked and talked, instead of letting you watch the game in peace. And it really is exciting. Everybody is so desperately in earnest. But they don't long remain serious.

One has heard it said, "There's a funny side to most things, if you can only see it." The Melanesians always see it! And the joke of jokes, which never, never palls, is a tumble! Of course they are extremely sorry if any one is hurt, but they do love to see people fall down--white or brown, no matter, but perhaps white for preference. I suppose they look on us as rather superior, dignified folk, and that adds to the fun.

You may catch English words every now and then among the Mota. The boys pick up the white men's phrases, and like to air them. Not only do you hear then talk about "Corner" and "Free kick," but I believe that occasionally, "You cuckoo!" has been heard--or something curiously like it!

Notice how graceful the natives are! They may be climbing trees, or rushing about in the football-field, or scrambling over the rocks, or racing one another; whatever their occupation, their attitudes are full of an unconscious grace, and the whites are apt to look rather clumsy in contrast.

Hurrah! There is a goal for us, and the boys fairly dance with ecstasy. In Mota, by the way, we don't say we have kicked a goal, but that we have placed a pig for the adversary's eating. If the opposing team gets the next goal, we say that they have eaten our pig, and the boys count up their [50/51] victories by the number of their uneaten pigs. For instance, this season we have been very lucky, and scored thirty-three goals to our opponents' five. The boys' view is that the enemy has eaten five of the Mission's pigs, and so the Mission has only scored twenty-eight!

The girls are not out here to-day, or you would see some enthusiastic spectators. They scream with laughter every time a player receives the ball on his head, and oh, how they enjoy it when the leather comes bounding in their direction! They pretend to be terrified, and the joke lasts for a good ten minutes.

What's that? You're sure you heard a small boy speak of the Head of the Vanua as "Cullwick," without any prefix! Well, it would be more wonderful if you had heard one of our boys use a term like "Archdeacon" or "Mister" in speaking to or of anyone. It is not their lingai--you know that word now!--they know no titles in the Islands, and if they did turn suddenly formal, believe me, it would mean nothing. They show their respect in obedience and attention, not in polite forms of speech. At first it does sound a little odd, but very soon you get used to it. The Bishop and the doctor alone receive their titles from the Melanesians. The other day one of the girls brought a letter to be posted which she had written to a clergyman who supports her. The envelope was addressed quite simply to "William Robert Norbury!"

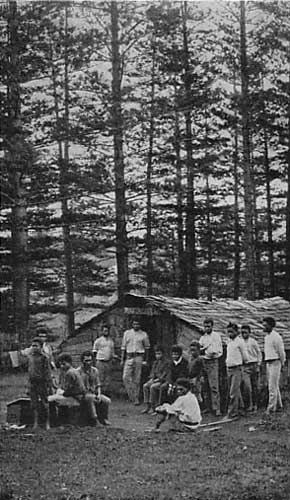

Speaking of the girls reminds me that I must hurry you away from the football-field to see what they are doing: they are not far off--only on the opposite hillside. After writing-school, the girls always go with one of the ladies (who take it in turns to accompany them) to where the wild tobacco grows thickly, for they use the soft dry sticks for firewood, or lito, as it is called.

Here we are in the midst of them. You can only catch glimpses of bright frocks among the shrubs, [51/52] but you hear the snap-snap in every direction. They pick up a heavy branch, and then knock it against a log or stump till it breaks.

Gradually, as one after another decides that she has collected enough, the knocking ceases, and we know they are tying up their bundles.

Now they emerge from the bush, each with her bundle of faggots--some are very big and heavy, others rather meager. Some are tied with cord, others with the strong stem of a trailing creeper that does as well. Do you notice, some of the girls put their bundles on their heads, and march along at a swinging pace, while others carry them on their backs? The difference is interesting; it is the northerners who carry on the head, the southerners on the back; each follows the way of her people. So home we wend cheerfully, and pretty soon the five-o'clock bell rings, and fires are lit, and kettles put on to boil.

Tea is at six--in hall for the men and boys, but the womenfolk stay at home, and have it in their own houses. It may be as well to remark that we don't keep servants, but all work together; and with a little training our brown daughters become very handy and useful. Some can make bread, cook a joint of meat, fry potatoes, poach eggs, etc., quite nicely.

Evensong comes at seven, and, after chapel, school. The subjects are various: the Catechism, Old Testament history, Church Services, and sometimes "Things of this world"--a nice wide title that gives scope for practical illustrations and experiments which delight the youngsters' hearts. It is impossible to go deeply with them into any science, but I have heard of lessons on a leaf, a magnet, a thermometer, the eye, the stars, and other subjects, which have all aroused keen interest.

EACH WITH HER BUNDLE OF FAGGOTS (p. 52.) Wednesday is always a half-holiday, and song-singing take the place of evening school. We chiefly use the good, old-fashioned melodies, such as [52/54] "Auld Lang Syne," "Away with Melancholy," "Oh, dear, what can the matter be?" and so forth, putting simple Mota words into the air. All Melanesians are music-lovers, but native music is not like the European kind, and every accidental is at first a stumbling-block. However, they quickly learn to sing well in parts, unaccompanied, and seem never to weary of doing so. We use the Tonic Sol-fa, and if we could give a little more time to it, the girls and boys would soon read as quickly from sight as they can sing by ear.

At quarter-past eight a bell ends school, and a hum of many voices arises in every house. It is preparation-time, and all are learning aloud in a high monotone their repetitions for the morrow. A quarter to nine rings preparation over. The boys retire to their nat-imas, and the girls amuse themselves in their own rooms till the Bell matur (sleeping bell) warns us that in twenty minutes the hour of ten will strike, and lights must be put out.

You shall come round and peep at our brown lads and lasses tucked up for the night. They don't sleep in beds like white folk. Just a mat spread on the floor, or at most a sloping-board, and they put a funny little hard pillow under the head, roll themselves up in three or four blankets, and so travel to the Land of Nod. Perhaps a tuft of fuzzy hair or two bright eyes are visible, but often head and all are covered up when we take our last look round.

"Good-night, my children!"

"Good-night!"

"God bless you all!"

"God Ni vawia iniko mulang! [God bless you too!]"

With that chorus of happy voices in our ears, we leave our family to rest.

When all is quiet, the men gather in chapel for compline, and so the peaceful every-day ends, as it began, with Confession and Thanksgiving.

It is a fortunate thing that you happened to come in September, because there is almost always a wedding-day before the Southern Cross starts on the last voyage of the year, and weddings at S. Barnabas are not common events.

There are two couples to be married to-day--Isabella and Martin, from Ulawa, and Mary and Macey, from Vanua Lava--one pair from the north, and one from the south.

A wedding spells a holiday and a feast, so it is looked forward to and enjoyed by the whole school. Who do you think enjoy it and look forward to it the least? The brides! That doesn't seem right, does it? But I'm afraid it's generally true.

The fact is, the Melanesian customs about engagement and matrimony don't allow the bride any voice in the matter of her marriage, and that's rather hard lines. Sometimes the boy also has very little to do with it, but the girl always less! In many islands the engagement takes place while they are quite small children, and it is arranged by the fathers and uncles. The boy's uncle offers, maybe, two pigs in purchase of a wife for his nephew, and when the value of the young lady has been agreed upon, and the last string of shells, or the last pig, has been paid over, she becomes the property of her future husband, and his wishes are now law to her.