From Mission Life: An Illustrated Magazine of Home and Foreign Church Work, ed. Rev. J. J. Halcombe, M.A., Volume III, Part I (new series), London: W. Wells Gardner, 1872, pages 1-23. Transcribed by the Right Reverend Dr. Terry Brown, Bishop of Malaita

Church of the Province of Melanesia, 2006.

SOUTHERN CROSS, October, 1871.--MY DEAR SIR,--My present communication contains the account of Bishop Patteson's martyrdom at Nukapu, near Santa Cruz. We have also lost the Rev. Joseph Atkin, and a native teacher named Stephen.

Of the changes which will follow upon the terrible blow under which we still reel I can form no idea, and it would be rash to speak.

We are now off Spirito Santo, with light winds, rains, and calms. We have twenty-seven Solomon Islanders on board, and three Mota teachers. We have been out six months, are very weary of our voyage, and are getting rather short of provisions.

It is a terrible price to pay for what ought to have been done long ago; but the Bishop's death will at last open people's eyes to the state of exasperation these natives are now in, owing to the violence practised against them by these labour-seekers. At this very time we are unable to go to our best yam depôt on account of the visits of these lawless vessels. I hope to keep you informed from time to time, of all that takes place here.*

C. H. BROOKE.

[Footnote: * We are obliged to reserve for our next number all those portions of Mr. Brooke's paper which do not bear immediately upon the sad tidings which gives to it such a painful interest at the present time. Three articles kindly furnished by him last year will be found in the March, April, and May numbers of Mission Life for 1871. In the August, September, October, and November numbers will be found full accounts of the recent progress of the Mission, and also Bishop Patteson's memorial on the subject of the so-called Polynesian emigration.--ED.]

The plan of this year's voyages was as follows:--

1. "Southern Cross" takes Bishop, Rev. C. Bice, Banks' Islanders, and those from New Hebrides, with Wadrokal and family, together with Gwaoska, Palumala, and my boy Simeon Nonia to Mota, landing the New Hebrides lads on the way. Vessel return empty to Norfolk Island.

2. Embark Rev. J. Atkin and Rev. C. H. Brooke and Solomon Island party. Call at Mota, embark Bishop and Rev. C. Bice with W. and party. On to the Solomons, viá Santa Cruz; leave Mr. Atkin [1/2] at San Cristoval, and Mr. Brooke at Florida. Thence to Savo; land W. and party. "Southern Cross" back to Mota. Visit New Hebrides, Mr. Bice staying for a few days at Leper's Island. Collect Banks' and New Hebrides lads; leave Bishop at Mota; vessel return to Norfolk Island with Mr. Bice and boys aforesaid.

3. Vessel go north again; pick up Bishop at Mota, on to San Cristoval and Florida to embark Messrs. Atkin and Brooke. Return to Norfolk Island and New Zealand.

So man proposed. We shall see how God disposed.

The vessel returned from her first cruise on Whit Monday, reporting all well, but voyage north very long and tedious. The accounts from New Kohimarama (Rev. George Sarawia's station at Mota) were not so satisfactory as they had been last year; but we shall hear more about it when we land there in the course of this voyage.

The Rev. J. Atkin, Rev. C. H. Brooke, and about twenty-five Solomon Islanders, some twenty of their fellow islanders having expressed a wish to pass the winter in Norfolk Island, left that place on Whit Tuesday. As usual, we voted the embarkation at Norfolk the most unpleasant and precarious portion of the voyage. Heavy was the surf, and many of us got a wetting. Mr. Atkin, upon whom the onus of this part of our work devolves, had a hard day's work in the water, salt and fresh; and at last we bid farewell, not without tears on the part of the more tender-hearted among us, to our home and friends. This was May 30th.

Favoured with fair winds, we reached Mota on June 7th; on shore early. The Bishop had only just returned from a voyage to Santa Maria in the boat set apart for the use of the sailor of our party, William Qasfar, who will thus be able to take Rev. G. S. about to the various islands of the group. The Bishop looked well, but felt fatigued with his uncomfortable, tempestuous voyage, and the long walk at its termination. Mr. Bice also looked well, and was enthusiastic concerning the earnestness of some of the natives of this island. The Bishop and he had been stirring them up, telling them it was high time for them to decide between the two religions. The result was that a class of adult catechumens had been formed, and there seems to be little doubt that many of the elder people are in earnest. This state of things, together with other reasons, decided the Bishop upon remaining in Mota while the vessel proceeded on its first northern trip. Wadrokal, also, would stay and finish a house that he was building in the Nenone fashion, for the enlightenment of the Mota people. So we embarked again without delay, Mr. Bice going with us in order to make the tour of the islands visited on our annual cruise. Edward Wogale, who was to be my companion at Florida, also went with us.

The principal topic of conversation during our few hours on shore, [2/3] was the depopulation of our Mission field by labour vessels. One of these vessels had visited the island during the Bishop's stay. She was from Fiji, bringing a letter of recommendation to the Bishop in favour of the captain, who actually asked the Bishop's aid in getting a cargo. The extremely Christian character of planters in general, and of a certain lady planter in particular, was duly set forth by those of the party who landed. The latter is said to evangelise her property by reading the Scriptures to them in the English tongue. To hear these good people talk, one might suppose that they were the Missionaries, and that we were those who would interfere with their spiritual work.

Is it to be expected of fallen human nature that it will be scrupulous in the manner of obtaining a cargo, every item of which is worth from £12 to £15 a-head in the market?

I write this on shore at Florida, where for the first time these "Snatch-snatch" vessels, as the natives call them, have begun their work. I have the names of fifty who have been taken from part of the island. Some went of their own accord, others to barter, but were seized and put below hatches, some tobacco or pipes or a hatchet being thrown to their friends in the canoe alongside. Among those who were thus entrapped were Manoga and Lave, whose names are already familiar to your readers. Now Lave was so little enamoured of his new berth that at night he jumped overboard, and swam ashore a long distance, at imminent peril of his life. From him I learn the following particulars: That he and Manoga paddled off with a view of trading with the stranger, but when they discovered what kind of vessel they had fallen upon, Manoga shouted to the people in the canoes, to be off! upon which M. was dragged back from the bulwark and silenced. Among the various means employed (on this and similar occasions) to ship the destined labourers, were these; harpooning, upsetting, and sinking the canoes, a noose being sometimes slipped under the canoe; at Boromole (near the "Curaçoa's" anchorage) a gun was fired, at whose report the frightened natives jumped into the sea: whereupon a boat, lowered for the purpose, picked up the swimmers, and put them on board.

The only engagement entered into between the "snatchers" and the "snatched" on this occasion was the holding up of two fingers by the former, a gesture which Lave chose to construe into two months, but which of course was meant to convey two years. Seeing a Christian cap upon Lave's head, the Captain asked him whence he got it; and upon his answering, "Bishop and B-----," told him to tell his people that if they behaved quietly all would be well, and that in two moons (?) they would be returned. Lave, however, got home before that time. As to the internal arrangements of the "snatcher," Lave says that the passengers were much crowded; that there were two decks or tiers below; that the muzzle of a gun was protruded through the bulkhead at each [3/4] end of the hold, which the labourers-designate were informed were for them, if they were not quiet; that the food given out was insufficient for the whole party; and that the humour of the men was various, some being cheerful, some sulky, others angry; that he and Manoga had both agreed to jump overboard, and swim ashore at night, but that at the last moment M. was afraid of the sharks. This was the news which greeted me on my arrival here, and I am constantly asked concerning the probable fate of the "snatched," and "Are these men the friends of you and Bishop?" and "Have they received the new religion, or not?"

We left Mota on the same day, bound direct for the Solomons, our visit to Santa Cruz being postponed till we should have the Bishop with us.

A very gentle breeze wafted us to Jugi on Monday, June 12th, where we landed a boy, and then stood over to Wano, San Cristoval. The wind falling still lighter, Mr. Atkin lowered his whale-boat, hoisted sail, and, with Mr. Bice and a select party, went on shore, bathed, and interviewed the people of the place, it being Mr. Bice's first tour among these northern islands. Here we left Stephen, Joseph, and Samuel, and then started for Florida, which we reached next day, the 14th, from N. I., having travelled a distance of about 1,400 miles. We were at once boarded by a party of clamorous friends, among whom were Takua and Sauvni, who immediately opened their treasure-bags, the invitation to trade being responded to by our white crew, even to the neglect of their duty.

We were a large party for the shore: Dudley, Charles, Simeon, Alfred, Takisi, Marapile, Salea, Babaleo, Parapolo, Bula, Rev. C. Bice (to look round), and Rev. J. Atkin, captain of the boat. Many and weighty were the impediments, but, with the aid of my new little boat, "Na Lionto"--"The Goodwill," we all landed at once. There was no attempt to steal or snatch anything, although nothing would have been more easy. The gunwale of the boat was hidden from stem to stem by black hands, which, however, refrained from officiously carrying off any article, so that I was able to select friends, and entrust to them the porterage of our goods, which in every instance was faithfully performed.

My little centipede of a house, which I had anticipated might have been burnt or tapued to desolation, still stood upon its array of crooked legs. Its interior was swept and in good order, while the worthy housekeeper, Subasi, sat on the threshold, waiting for the marks of approbation which he felt were his due. . . . . . .

September 24.--An event has just occurred of such awful magnitude as to eclipse all others. Leaving them, therefore, I shall confine myself to the narration of certain facts, and rumours founded on fact, which came under my notice at Florida--facts which form a fit prelude to the [4/5] terrible tragedy enacted before our eyes on the 20th inst., and under whose influence we still reel.

1. On July 11th, I was informed that a "Sydney" vessel, having a large number of blacks on board from Isabel, Javo [Savo], New Georgia, &c., had killed nine natives at the western end of the island. The names of the men were given me at the time, and were so often correctly repeated by successive relators of the affair, that I soon lost all doubt that they had been actually killed.

2. On the 13th, Takua came to me, in alarm and anger, to say that the kill-kill vessel had anchored about four miles from Boli, being hidden by a large rock called the Pig. To-morrow she would be here, and what was he to do--"to kill, or to be killed?" And "how was it that Bisopé and you came first, and then these slaughterers? Do you send them?" I told him it was our wisest course to remain quietly on shore; but that if they landed, and attempted to burn house or kill man, then "kill! kill! utterly!" "Your words are the words of a chief," said he, and retired. When we three Christians were gathered together in my little house that evening, our prayer to be kept free from danger acquired a new meaning.

Next morning, to our great relief, the vessel was reported in the distant offing, heading for Malanta. On the 17th I visited the village of the murdered men, where the poor desolate women were still holding a tangi over their lost husbands, sons, and brothers. The simple creatures offered me a pig if I would avenge them. The homes of the slaughtered were laid waste, cocoa-trees felled, houses burnt, and canoes battered. The people said they were very angry, and would take vengeance upon the first vessel that came in their way. Their plan of throwing fire on the sails of the vessel did not appear to be very practicable.

3. On Sunday, August 13th, a vessel very much like the "Southern Cross" hove in sight from the westward. Large numbers of people have already gathered together to wait for the Mission vessel, the excitement was very great as she made a bold tack in-shore. We then perceived that she was a stranger, and I warned the people against "paddling her," as they say here, lest they should meet the fate of the Boroni and Olevuga victims. At length she hoisted a flag, and some canoes put off to her. Dudley Lankona reported that they tried to induce him and others to go, saying that Bishop and B----- were bad, but that they themselves were very good, and that there were lots of tobacco and pipes in store for any one who would go with them. Dudley and his fellow paddlers came off empty, with the fruit, &c., unsold, which did not add to the popularity of that class of vessel. While I was sitting on the beach, waiting the return of the paddlers, another vessel appeared white on the horizon. This was reported by No.1 to be [5/6] a "killer," whereat the temper of the people was naturally much irritated.

Next morning, to my annoyance, there lay No. 2, becalmed within easy paddling distance. Dike was very anxious to lift a war-fleet, and go and kill, but I said I would pull off in "Na Lionto," with my disciples, and ascertain the true character of the vessel. She proves to be the E-----, M-----, master, of New Zealand, but lately from Tanua [sic], New Hebrides, where M----- has property, for which he was seeking labourers. There were one or two Aubryn [sic] lads on deck; but Charles said to me there must be some more inside (the hatches being closed). I rather pooh-poohed the idea; whereupon he said, "Look at all that food," pointing to a great copper of yams; "that's too much for those we see." He was right, for M----- had visited St. Cristoval, and had acknowledged to the Rev. J. Atkin, that he had twenty-nine natives on board. Poor wretches! what a purgatory my two hours' visit must have occasioned them! Captain M----- was naturally hurt at the bad character given him by the other vessel, and honestly said, "If I got a chance to carry off a lot of them I'd do it, but killing isn't my creed." He said he wanted six of these fellows. I said "if any choose to go, let them go, by all means." When I informed him of the plot against his life, he said, "By G-----! Let 'em come! When I hinted at the possibility of the natives attacking him, he pointed to the ceiling of the little cabin aft, which was well-nigh covered with about six muskets, "And that's only a few of 'em: we've got lots more. Let 'em come, and we'll give it 'em pretty strong! I have my doubts about its proving all give. I imagine he would have to take a great deal, for his crew were a most lugubrious-looking set of men. The mate was a broken-down captain, with one of his eyes fixed in an eternal stare, a face of preternatural longitude, and a body of considerable length, without life enough to animate it throughout. There was not a healthy-looking hand among them, except a fat half-caste, who M----- said was getting stupid on it. I was invited into the cabin, where M----- poured me out some pure gin, helping himself at the same time. He drank, and wished me "success!" I said I was sorry I could not return the compliment. I should think he would be a kind master--this jolly, lawless, smuggling Scot, who from his decks surveyed a fine canoeful of about twenty souls, or rather bodies, from his point of view, exclaiming: Ah! my fine fellows, if your friend wasn't here I'd have the whole lot o' ye! Just a nice day's haul!" Captain M----- expressed it as his opinion, that it did them good to take them away from their homes; to which I replied, "Possibly so, but that we preferred their going to Norfolk to any other place. His retort was, "The planter must live!" "Well, if black labour is necessary, you must go and get Chinese, who don't mind leaving their homes, and are, moreover, a [6/7] harder working, more intelligent race." "So they are; and I believe it's because they have been taken away from their homes more." It was some little time before he discovered that I was a clergyman, for (owing to the climate) there was nothing in my dress to indicate it; at length he found it out by some expression of mine. "Oh, you're a Missionary, are you?" He must have thought I was making cocoa-nut oil on shore. "Yes," I said, "I am." "Well!" he exclaimed, "wherever ye go now-a-days there's Missionaries; who'd ha' though you'd got this fur down!"

From M----- I learnt that the vessel of yesterday was a Queensland vessel, with a dignitary on board called a Government Agent, of whose majesty my Scot spoke in awful whispers. Considerable trade was done on board during our visit. I found the people on shore in a very bad humour; Takoa sent for me to go and talk with him. He asked me how many men there were on board, and wanted to know a reason why he should not go and attack them; for they were evidently bad men, and would the Bishop grant it? &c. He then went and furbished up an old musket, given him by some most indiscreet person on board H.M.S. "Curaçoa". Dikea also brought forth his, and asked me to get out the ramrod for him, which I did, at the greatest risk to the entire weapon, for the muzzle crumbled under my touch.

4. We had scarcely recovered from the perplexity and disturbance caused by the above intrusions, when we were startled anew by a report that four men had been killed at Vura, about five miles on the Pavu side of where I was staying. The names of the victims were given with the same precision as before. They were killed on the 17th of August. Five men had "paddled the vessel." The survivor I saw. He was a youth named Sorova. This is his story:--

In the afternoon two canoes paddled the vessel; in one, Sorova and Pangesi; and in the other, Kili, Kopi, and Niagana. They went off to trade, but the vessel, which had already traded at a neighbouring place, refused to buy anything from them. Sorova's canoe was moored astern, and as he looked up he saw four blacks (from Ysabel, he thinks). Presently a Sydney man got down from the vessel, and sat in the bow of Sorova's canoe. He then stood up and capsized the two canoes, and the men all fell into the water. The white man caught hold of Sorova's belt, which broke, and enabled him to seek refuge right under the stern. There he remained, until, watching his opportunity, he struck out for the shore, when the vessel made a shoreward tack. He saw a boat come round from the other side of the ship with four men in her (he says white men, but that may mean light-coloured natives) who proceeded to kill his companions, the order of whose death he gave me:--1. Kopi, 2. Kili; 3. Pangesi; 4. Niagana. This took place about twenty yards from the vessel. The victors were first belabored with the oars, then fallen upon with tomahawks, &c., and finally beheaded, their heads [7/8] being taken on board, and their bodies thrown to the sharks. This done, the vessel tacked about as if looking for something, which Sorova had a strong suspicion was for himself; for "were there not five men? and only four heads?" "But how is it they did not see you?" I asked him. "Because the waves hid me," he answered.

5. The Bishop was now overdue, and the one cry was: Why do all these vessels come, and the Bishop does not come? On August 28th, there was a shout of two vessels. Next morning a large black brig was laying a little to leeward of the landing-place. In spite of warning, one small canoe with five paddlers went off to the vessel. Before they reached her we saw two boats pull off from the brig, which fell upon the canoe, one on either side. A conviction of the sickening scene which was impending prevented my looking steadfastly out to sea; but presently the whole populace on the beach gave a series of staccato shouts, as if they were all being beaten with one rod. "They are killing our friends before our eyes," shouted Dikea. "Away! Let us have vengeance! And in the twinkling of an eye the whole mob rushed into the big canoe-house, and launched a war-fleet, every man seizing the first weapon which came to hand. I caught passing glances of friendly faces distorted with rage; among others that of Subasi. They were at sea with a shout in a few minutes, and flew across the calm water, Dikea standing in the middle of his canoe, bearing a long ebony spear, and urging his people to the fray. Fortunately, the boats did not wait for them. They were hauled up and the brig went off, with all sails set, in a wonderfully short space. The names of the victims: Dokosi, Langasi, Lilia, Puko, Upe. "Five fighting men gone!" said Takua.

Thus we have had fifteen men taken away under false pretences, and eighteen murdered in cold blood, in this small island in a few months' time. Had the people taken my life in exchange, who would have been surprised?

Then arose the tangi mate, and the smoke of the kere vale (house burning). Every one was red-eyed; all--men, women and children--were crying, some in rage and some in sorrow. "Let not their pigs be killed!" said Takua; "we will give them to Bisopé, and he shall avenge us!"

As I sat in my house in the noonday heat, utterly perplexed and very sad, Dikea came in, violent and angry, and said, "My humour is bad because Bisopé does not take us about in his vessel to kill-kill these people! I said, "Talk to him about it; he would not suffer his vessel to be desecrated by such bloody work. These men do only what you have done. You killed eight men when I was here before, and took their heads." He turned on his heel, and leapt down the ladder without another word.

That was indeed a gloomy afternoon. "Why does not the Bishop [8/9] come?" sighed Edward Wogale and I, and as we walked sadly in-shore (the poor fellow's eyes being unequal to the glare of the sandy beach), and, reaching a pretty spot where a stream rushed babbling by, we sat down, two melancholy men, upon a boulder-stone. What explanation could I offer to these fierce men and wailing women, whose cries fell upon our ears as we sat praying that our sadness might be turned into joy? "Why does not the Bishop come? Eleven Sundays gone now!"

Next day our hearts revived. There was a strong trade blowing, and, as I sat and wrote, the wind increased, and hummed in the feather-headed cocoa-nut trees above, and puffed in at my little door, swinging the hanging clothes and scattering books and papers. I felt that the "Southern Cross" was near. I paused, now and again, for the gathering shout of the hill-tops. Yes! There it is! Hurrah! Thank God! "It is not Bisopé!" they cry. Poor creatures! they have been too often deceived for that! I go out upon the beach, and see a bellying sail rushing on toward us. Is it going to pass seaward or shoreward of Laga-le?* [Footnote: * A small islet off Belago. Our vessel is the only one which passes inside of it.] Yes, shoreward it comes! Thank God, for this joy of the morning! The people are all melting from their stern mood of yesterday. As, from the top of his coral wall, we watch her pressing on, Takua says to me, "Let Bisopé only bring a man-of-war, and get me vengeance on mine adversaries, and I shall be exalted like--like--like--our Father above!"

"Yes, that's Bisopé!" I said, and left him, to put up a few things.

And the Bishop truly it was. He asked me a few hasty questions, and gave me hasty news. "Are the people quite friendly?" "Yes, quite so." "Then we'll anchor the vessel." "Can you sleep a night on shore?" "Yes; meet me a Sara in an hour." And off went the boat to the vessel, and the vessel to cast anchor at Sara.

The reaction from yesterday was very great: the people clasped my hand, exclaiming, "How good and kind your vessel is! and how cruel are the others!" and their tears flowed for joy to-day, as they had done yesterday for sorrow.

When we met in the afternoon, the Bishop told me that the island of Mota was in a most happy state. Young and old were in earnest in wishing to cast off their old bondage, and enter into the glorious liberty of the children of God. He had baptized as man as ninety-seven children on one occasion. He was constantly waylaid and asked questions. The common talk in the the gamals and salagoros was of what the Bishop had said the previous day. Nothing could be brighter or more hopeful. The Bishop saw the fruits of his labours. We were to stop at Mota on our return, for there more baptisms were to take place; and perhaps George would be ordained Priest. Such were our happy plans. Home letters completed the joy of that welcome hour.

[10] The vessel was of course crowded with people buying and selling, and our decks resembled a busy fair. Next day we made up our party of ten.

We reached Savo next day, and the Bishop left Wadrokal and his party to form a school and Christian nucleus there. It is a small island, with a language quite unlike any of the surrounding dialects. For instance, the term for man is mapa; for moon, Kugega. Wadrokal is a fine strong fellow, full of zeal, and possessing a cheery, genial manner. We hope he will do a good work there. He was an old scholar of the present Bishop of Litchfield. Labourers had visited the island, and had used violence in taking away their freights.

Thence we went to Ysabel, where the Bishop had an interview with Bora, the chief of the part of the island which we visit, but could not wait to see Capel Oka, who had crossed from Savo, and was inland.

On the 4th we spoke a small schooner called the "Cambria" B.C. (?) with natives on board for Queensland.

We now turned our thoughts towards Santa Cruz. A Labourer, which had called at San Cristoval, about two months ago, had told Rev. J. Atkin that he intended to go to Santa Cruz. This caused us uneasiness, for, as many of your readers are aware, they have a strong prejudice against letting any of their people go, it being now over twelve years that the Bishop has called regularly, with few exceptions, but in vain. Their fierce, impulse temper has been too often shown.

At length, on Friday the 15th, we sighted the pastille-like volcano, Tenakula, which was very active, and afforded us a grand spectacle; but the wind was blowing from a most unusual quarter, and we were detained near to it for four days, at the end of which time we came up with Nupaka [sic], one of a group of small islands near Santa Cruz, where we call first because the people here understand Maori, being Polynesian, and we can generally get hold of some one to act as interpreter at Santa Cruz, where we cannot make ourselves understood. No canoes put off--an unusual thing. But four hoved near the reef.

The Bishop, supposing that the did not understand the movements of the vessel, owing to the unusual wind, put off in the boat at half-past eleven, taking with him the Rev. J. Atkin, Stephen Taroaniara, James, and John. We watched their movements from the vessel.

After gaining the canoes, the whole party moved slowly shorewards along the reef, the boat being unable to cross the reef because it was low water. In about two hours' time the boat pulled off to us. The Bishop was not in her. An arrow was stuck through John's cap, and Mr. Atkin said "We are all hurt."

This was the account:--Unable to land in the boat, the Bishop had gone ashore in a canoe belonging to two chiefs whom he knew--Taula and Motu--leaving Mr. Atkin in charge of the boat which remained in company with the canoes, then reinforced, and four in number as before. [10/11] In about three-quarters of an hour, a man suddenly rose in one of the canoes, and saying "Have you got anything like this?" let fly an arrow which was accompanied by a volley from his seven companions, the boat being about ten yards distant from the canoes. Mr. Atkin was shot in the left shoulder, John in the right one, and Stephen trussed with six arrows in his shoulders and chest.

These arrows are about a yard long, heavy, and headed with human bone, acutely sharp, so as to break in the wound.

The Bishop was still ashore. Mr. Atkin, with Mr. Bongarde, the mate, Charles Sapi, Joseph Wate, and others, put off again in the boat, well armed!--for such is the resource to which these wicked traffickers reduced us--to ascertain his fate. Meanwhile I extracted five arrowheads from Stephen's body; the sixth, in the region of the chest, was beyond my reach. "Kara i Bishop!" exclaimed the poor fellow. "We-two, Bisop!" The tide had now risen, and we saw the boat pull over the reef. No canoes approached--but a tenantless one, with something like a bundle heaped in the middle, was floating alone in the lagoon. The boat pulled up to this, and took the heap or bundle out of it and brought it away, a yell of triumph rising from the beach. As they pulled alongside they murmured but one word, "The Body!"

Yes, our dear Bishop's body, wrapped carefully in native matting, and tied at the neck and ancles. A palm frond was thrust into the breast, in which were five knots tied--the number of the slain, as they supposed, or possibly of those whom his death was meant to avenge.

On removing the matting, we found the right side of the skull completely shattered. The top of the head was cloven with some sharp weapon, and there were numerous arrow-wounds about the body. Beside all this havoc and ruin, the sweet face still smiled, the eyes closed, as if the patient martyr had had time to breathe a prayer for these his murderers. There was no sign of agony or terror. Peace reigned supreme in that sweet smile, which will live in our remembrance as the last silent blessing of our revered Bishop and our beloved friend. We buried him next day at sea.

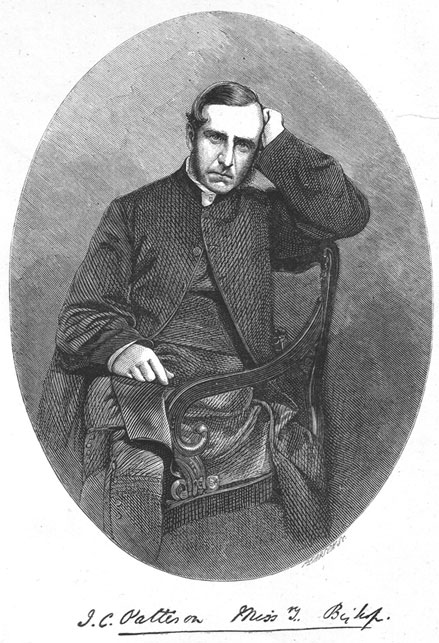

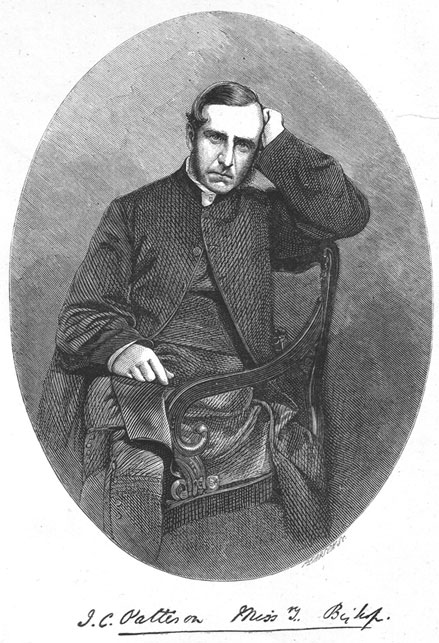

JOHN COLERIDGE PATTESON.

THE GOOD SHEPHERD GIVETH HIS LIFE FOR THE SHEEP.Our loss was not yet complete. Mr. Atkin become suddenly worse on the 26th, and spent a night of acute pain; the whole nervous system was being jerked and strained to pieces. Almost leaping from his berth upon the floor, in his intolerable agony, he cried "Good bye!" and lay convulsed upon a mattrass [sic] on the floor. About seven o'clock on the morning of the 27th I asked him, would he have a little sal volatile? "No!" A little brandy? "No!" Did he want anything? "To die!" Those where his last words, and after another hour's acute suffering he passed away.

[12] Our thoughts now turned to Stephen, who was very restless. Joseph Wate, his nurse, was most attentive to him. That night his rest was destroyed by spasmodic convulsions; the struggle between his physical strength and the disease being violent in the extreme, and it was heartrending to be unable to relieve him in any way. He died at twenty minutes to four on Thursday, the 28th, and the two friends were buried at the same time.

The looks like revenge, especially when coupled with the fact of the proposed visit of the "Labourer"; but while we condemn the unscrupulous conduct of those kidnappers, there is but little excuse for those two chiefs who took the Bishop on shore, for they knew him well. But then, again, who can tell what terrible law of utu prevails among this wild race, which may be satisfied only with most precious blood? Mr. Atkin overheard some remarks made by one of these men, to the effect that the Bishop was tapu, but did not understand its purport at the time. A small kit of yams was put into the boat by those who fired upon it!

With numb hearts and shaken nerves, we worked our lonely way to windward. Our water being very low, and our yam-bins nearly empty, the vessel was very light and fell to leeward in the most disappointing manner, helped by a strong set, insomuch that when we hoped to have found ourselves, and indeed believed ourselves to be, off Great Banks's Island, within nine miles of Mota, we discovered that the land we had made was Espiritu Santo, forty miles leeward! We reached Mota, however, at last, on Wednesday, October 4th.

Sadly in want of food, we were disappointed to hear that there was none on the island, and that they had to buy it from their neighbours. Moreover, the news of the Bishop's death stunned all those who would otherwise have given us help.

The Rev. George Sarawia had had trouble too. Edmund Qarat, who should have been his right hand, the cleverest of our converts, but with ungovernable, or at least ungoverned passions, had deserted the station and was disgracing his Christian profession. William Qasfar, who had been left at Saddle Island with a boat, and orders to take George about, had not been near them for some time. All, all, looked black. If any one needs the Church's earnest prayers at this time, it is this faithful and wise deacon, left in loneliness and sorrow, and with heavy responsibilities weighing upon him. Among the letters he entrusted to my case was one to the Bishop of Lichfield, his first tutor.

Our want of food and water prevented our staying at Mota as long as we could have wished, and in three hours' time we were working up to Star Island in the hope of obtaining supplies there. But, although we had a good working breeze, and the distance was short (about forty miles), we reached it only the second night, too late to go ashore, the schooner having little more hold on the water than the toy ships [12/13] manufactured by our lads out of their cocoa-nut husks, which strew our wake.

We determined, therefore, to press forward to our southern watering-place in the island of Aurora (which we are thankful to say has not disappeared) and which we reached this day (October 6th) at noon. We are now at anchor. This afternoon we worked very hard, and to-morrow we hope to fill up with water and yams, and start for Norfolk Island, where the terrible wounds will have to be re-opened, the awful tale re-told!

October 18th. Norfolk Island. We arrived here yesterday, turning the joy of our few friends into sorrow by the sad tale we have to tell.

The surviving members of the Mission met yesterday evening to decide upon the best course to be pursued at once. The law of the Church of new Zealand gives us the right of recommending a successor to the General Synod of the New Zealand church, a right of which we deem it just to avail ourselves; but of course nothing formal nor final resulted from our hasty conference. In this our emergency, we naturally turn for advice and help to the great and noble founder of the Mission. Meanwhile, the law directs that the work be carried on by the senior member, by order of ordination, of Mission staff--in this case the Rev. R. H. Codrington, who has declined the proposed recommendation of himself as successor to the vacant See.

GREVIOUS as are the tidings which reach us from the Pacific, they should neither take us entirely by surprise, or lead us to think that anything has happened the probability of which had not been clearly foreseen. The cost of pursuing the particular plan of action peculiar to the Melanesian Mission was duly counted, and has now been deliberately paid. All other European Missionaries have commenced their work amongst these islands by sending forward trained natives from some place already civilized. Landing them amongst their savage countrymen, they would leave them for weeks or months, sometimes for years, and then return, to find them either killed or surrounded by a body of attentive listeners, won by the earnestness and devotion to listen to the story of the Cross. When a footing had been thus made, Europeans, at a risk of life scarcely less, would go and settle with them, only too often to fall victims themselves to the suddenly-aroused fears, [13/14] or superstitions, or anger of those whom they sought to teach. In no way could the work be carried on without great and constantly-recurring danger.

The main difference between Bishop Patteson's plan and any which had ever been adopted previously, was that it concentrated all the danger upon the leaders of the enterprise. It was as chivalrous in daring as for more than twenty years it has been eminently successful in operation. But alas! the risk, especially in visiting new islands, was a constantly-recurring one. Again and again has Bishop Patteson's life, as so often that of Bishop Selwyn before him, seemed to tremble in the balance. Only a few years back two of his companions fell at his side, stricken down by a volley of arrows shot by the very people at whose hands he has now met his death, and who apparently think as little of shooting a poisoned arrow at a stranger as a schoolboy would of throwing a stone at a bird. Under ordinary circumstances, the only methods of defence trusted to, when precaution had proved useless, or confidence misplaced, was precarious enough; but on any occasion of special excitement or anger arising, they were evidently wholly inadequate. To call out to a number of fierce savages, with their bows full drawn, "Shoot away--all right" and to disarm them by the very appearance of amused unconcern; or to remain seated as a man rushed on with uplifted club, and to trust to the effect of dangling a few fish-hooks in his face, were methods of proceeding which, however successful on former occasions, were terribly inadequate to deal with men excited to a pitch of madness by seeing their friends and relations decoyed away and carried off they knew not whither.

It is only a few weeks since, in what to some might have seemed terms of exaggeration, we drew attention to Bishop Patteson's own report upon the subject of this kidnapping of the Islanders. In that paper he speaks of the greatly increased risk to himself and those with him. His work could only be carried on at all by assuming a confidence in the people he visited. His chief safeguard was in the manifest sincerity of his profession of friendliness. Well did he know what would be the result, if he happened to follow in the footsteps of those who had made and given the lie to similar professions, especially if they had professed to come from the Mission schooner.

Still he would not cease from his work; by anticipation he actually "prayed for his murderers," that allowances should be made for them, and his death was not revenged; and then calmly and cheerfully went on with his work, knowing that his time was in God's hands, and content to leave to Him the decision whether His cause would be the more advanced by his life or by his death.

For a full and complete memoir of the life and work of Bishop Patteson, the materials are, we imagine, unusually ample. His long-[14/15] continued separation from those to whom he was so closely united by ties of the warmest affection, led to his writing regularly and at great length. At the same time the brightness of his character, the exceptional nature of his work, and the singular clearness of his style, all combined to lend a peculiar charm to his letters and journals, and not seldom to give them an air of fascination and almost of romance.

There is but one man living who can produce such a life of Bishop Patteson as we hope to see.

In the letters and journals there will be missing links to be supplied, obscure allusions to be explained, hints to be followed out, narratives to be completed, theories to be discussed, and conclusions to be deduced. Bishop Selwyn, the originator and first leader of the enterprise, alone possesses all the requirements indispensable for such a task. Should he undertake it, the Church will owe him a debt of gratitude never to be repayed--a debt greatly enhanced by the knowledge of the serous tax upon his time and energies, which, in the midst of his present laborious life, such a work would entail.

The benefit which such a work would confer upon the general cause of Missions it is impossible to over-estimate. If the life of Mackenzie did much, what may we not hope from a record of heroism crowned with so ample a success as that which remains a standing memorial of him who has now passed from us?

Of the many graceful tributes of respect and admiration which the public press of this country have already paid to the memory of Bishop Patteson, a short biographical sketch published in the Literary Churchman* [Footnote: * See Literary Churchman, December 9th.] is especially remarkable for the amount and variety of the information which it gives, and the appreciation of his character with which it is written. The particulars of his early life seem to bespeak the hand of one who could write from personal knowledge:--

"John Coleridge Patteson, son of one judge and nephew of another, was born on the 1st of April, 1827, and brought up in a joyous, peaceful home, full of family affection and cheerfulness. His mother was Frances Duke Coleridge, daughter of Colonel Coleridge, of Ottery St. Mary, and sister to Sir John Taylor Coleridge. There seems to have been always a bright goodness and conscientiousness about him, rendering him beloved by all and thoroughly trusted: one of those boys about whom there is no uneasiness, and who grow up simply and evenly, and, though of excellent abilities, not attracting any extraordinary attention; studying dutifully, though not enthusiastically; and thoroughly boy-like in a wholesome love of sport, mirth, and exercise.

"He was educated first at the old foundation of Ottery St. Mary, and afterwards at Eton; and it may be worth remembering now, that at the last montem but one, in the throng of boys and carriages, Coleridge Patteson was entangled for a moment against the wheel of the royal carriage, and would have been drawn under it, had not the young Queen herself, with ready helpfulness, held out her hand: he grasped it, and the aid saved him. The Queen's carriage rolled on; and probably she never knew whom she assisted.

[16] "His College at Oxford was Balliol, but he afterwards became a Fellow of Merton, and so continued after his Episcopate began, until his father's death made his private fortune beyond the sum permitted to a Socius. He seems to have grown up with an unvarying purpose of taking Holy Orders, ever since he had, as a little child, longed to say the Absolution, because it would make people so happy; and no sooner was he ordained than he obtained the curacy of Affington, a small new church, freshly built on the outskirts of Ottery St. Mary.

"The place is in a rich and delightful part of Devonshire, within an easy walk of Feniton Court, where his family had established themselves on Sir John Patteson's retirement from the bench; and in the midst of many other relatives and friends, all fondly attached, and living in close intercourse. Nothing could have been imagined as more delightful to a young clergyman than thus at once to "dwell among his own people" and to have the fresh interest and zest of gathering a scattered flock.

"But a far higher call awaited him. He had been but two years at Affington when the Bishop of New Zealand made his memorable visit to England in 1854, the same which stamped the Missionary spirit on Charles Mackenzie, and was also the turning-point with Coleridge Patteson. He freely, and with his whole soul, offered himself to work under Bishop Selwyn; and his father, an aged man, though well knowing that there was little chance of their ever meeting on earth again, gave up his first-born son to His Master's service, with the fullest and most cheerful faith. His mother had been dead some years; but the home he left was one of united cheerfulness, brightness, and love, such as might to many have been a snare, by withholding them from the higher call; and yet the thought of it seemed, in future years, not to sadden but to brace him who left it. The love he had been nurtured in there came back as strongly as ever from the other side of the world, not in repinings, but expanding upon all who came in contact with it. It was already known that he had an unusual aptitude for languages: and so rapidly did he learn Maori, on his passage to New Zealand with Bishop Selwyn, that the natives, on his first arrival, asked the uncomplimentary question of one of the senior clergy of the Mission, why 'he did not speak like Te Patehana.' This very remarkable power, which almost amounted to the gift of tongues, together with a constitution congenial to warm climates, and a genius for seamanship, marked him out, in Bishop Selwyn's eyes, from the first as the chosen instrument for the evangelising of the islands, which, at that time, formed part of the then enormous diocese of New Zealand, which absolutely was like the clove of an orange, reaching from pole to pole."

Already Bishop Patteson had made more than one voyage amongst the group of islands which he was anxious to evangelize, and had fairly inaugurated the plan of operations, which has ever since been acted upon. The islands lying nearest to New Zealand and furthest from the Equator had for many years been occupied by European Missionaries, chiefly those of the London Missionary Society. But those lying nearest the Equator were quite uninhabitable by Europeans during the greater part of the year. To meet this difficulty, Bishop Selwyn had determined to cruise about among them during the cooler months of the year, and to bring away any of the native lads who might be entrusted to him, keep them in New Zealand during the summer, and then, before the winter set in, take them back to their homes.

[17] Bishop Selwyn made his first cruise amongst the islands in 1849. For some years he had been in the habit of visiting the various places on the coast of New Zealand in a little schooner of only 22 tons, the "Undine." In this tiny craft he safely accomplished the 1,000 miles which divided New Zealand from the Loyalty and other groups of the islands, and after cruising about amongst them for some time, and landing wherever there were no actual signs of hostility, he returned with his first five scholars, who were speedily installed at St. John's College, Auckland, an institution originally established by the Bishop for training young Maoris for the ministry.

In 1851, a new and larger vessel, the "Border Maid," having been obtained, the Bishop again started for a four-months' cruize, which he repeated in 1852 and 1853, each time bringing back a larger number of scholars. After his return from England with his new fellow-worker, and future successor in the work, he still continued for another six years to make frequent voyages to the islands, and to superintend the work at Auckland.

On two occasions during this time Mr. Patteson remained for several months at one or other of the islands to keep a winter school. Thus, both by his residence amongst the people, and by his constant and familiar association with the lads brought from the various islands, he gradually obtained so thorough an insight into the whole work, that the Bishop no longer hesitated to hand over to him the sole responsibility of carrying it on.

"I wish" he writes at this time, "you could see him in the midst of his thirty-eight scholars at Kohimarama, with thirteen dialects buzzing round him, with a cheerful look and cheerful word for everyone, teaching A B C, with as much gusto as if they were the Z Y Z of some deep problem, and marshalling a field of black cricketers, as if he were still the captain of the eleven in the upper fields at Eton; and, when school and play are over conducting the polyglot service in the Mission chapel."

The rare combination of mental and physical gifts needed in one who was to be at the head of such an enterprise was such as might well make it a matter of thankfulness that one possessing them all in so high a degree should be found. "The cool calculation to plan the operations of a voyage, the experience of sea life which would enable him to take the helm in a gale of wind, to detect a coral patch from his perch on the foreyard, or to handle a boat in a heavy seaway or rolling surf, the quick eye to detect the natives lurking in the bush, or secretly snatching up bow and spear, the strong arm to wrench their hands off the boat," were some of the minor qualification which had so often stood Bishop Selwyn in good stead, and which were not likely to be wanting in an ex-captain of an Eton eleven, who had served a seven years' apprenticeship to the work. Then, too, "his [17/18] peculiar gentleness, combined with firmness--the suaviter in modo, fortiter in re--so especially required in dealing with the native races;" his power of attaching others to him and himself to them, all combined to point him out as peculiarly suited to the work to which his whole life was now to be formally dedicated.

The consecration took place on St. Matthias' Day, 1861, in St. Paul's Church, Auckland, the Bishops of New Zealand, Wellington, and Nelson, officiating, and Bishop Selwyn preaching the sermon. The scene was altogether a very striking one, especially the actual moment of consecration, when one of the Melanesian lads--Tagalana* [Footnote: see next paragraph.]--came forward to hold the Prayer-book for the Bishop to read from, making himself a sort of living lectern for the occasion.

[Footnote: * In a letter written only last summer, one of the clergy of the Mission describes a visit which he had been paying to Henry Tagalana and his wife:--"Our party here," he says, "centres round Tagalana and his wife. He is the eldest of a large family, who have come in succession to the Bishop. The way of life of the eight Christians here is very pleasing. They live in one house, the best in the village. After bathing in the morning, they have prayers and a hymn, which, as they are all singers, sounds very well. In the evening, after prayers, which people stand outside the house to hear, Henry and William go and sit in the two or three principal places and talk to the people["].]

Long, doubtless, would Bishop Selwyn's concluding words dwell upon the mind of him to whom they were addressed, and well may many who heard them recall them now.

"May Christ be ever with you: may you feel His presence in the lonely wilderness, on the mountain top, on the troubled sea! May He go before you with His fan in His hand to purge His floor! He will not stay His hand till the idols are utterly abolished. May Christ be ever with thee to give thee utterance, to open thy mouth boldly, to make known the mystery of the Gospel! Dwelling in the midst of a people of unclean lips, thou wilt feel Him present with thee, to touch thy lips with a live coal from His own altar, that many strangers of every race may hear in their own tongue the wonderful work of God.

"May Christ be ever with you! May you sorrow with Him in His agony, and be crucified with Him in His death: be buried with Him in His grave, rise with Him to newness of life, and ascend with Him in heart to the same place whither He has gone before, and feel that He ever liveth to make intercession for thee, 'that thy faith fail not!'"

To realize the kind of work in which Patteson was from henceforth to be the chief actor, we must now picture him to ourselves in his various employments.

Here, for example, are two accounts, by different writers, of his method of proceeding on visiting an island for the first time, which will equally well serve the purpose of illustration, though referring to a period prior to his consecration:--

"Leaving his boat at some yards from the reef, where some hundred people are standing and shouting, he plunges into the water, carrying no end of presents [18/19] on his back, which he has been showing to their astounded eyes, out of the boat. He probably has learnt from some stray canoe the name of the chief; he calls out the name: he steps forward. The Bishop hands him a tomahawk, and holds out his hand for the chief's bows and arrows. The old chief, with innate chivalry, sends the tomahawk to the rear, to show that he is safe, and may confide in him. The Bishop pats the children on the head, gives them fish-hooks and red-tape. Probably he has with him a boy from another island, and brings forward this sample, and tries to make them understand he wants some of their boys to treat in like manner. Meanwhile the Bishop's eye is on the watch, and on one occasion he observed Mr. Patteson walking on inland too far, and the men drawing him on. He called him back, and afterwards said to him, 'didn't you see those bushes alive where you were going?'"

"The whale-boat is manned with four good rowers. The Bishop and the Rev. J. C. Patteson keep a good look-out whilst approaching the island; the natives having previously shown their willingness for communication, by lighting fires and calling. If, as the boat approaches, a part of them retire into the bush, with their bows and arrows, and send their women and children away, it is a bad sign; mischief is intended; but if all remain together, the Bishop and Mr. Patteson generally swim through the surf to the beach, leaving the boat at a short distance, the risk being, lest, touching the shore, the natives might detain it for the sake of the iron which they are anxious to obtain. After the party have landed, they distribute fish-hooks, beads, &c., to the chiefs, exchange names, write them down, &c. After staying a short time, they swim back to the boat. Thus an intercourse is begun. These preliminary visits are sometimes perilous. I know of two instances in which they were shot at--one at Santa Maria, the other at Mallicolo; but a kind Providence has always kept them safe from harm."

"The plan which he adopted when visiting quite new islands was to take absolutely nothing with him, except a book for writing names and words of the languages, which he kept in his hat, as the only waterproof receptacle about him: so much of what he did being done by the assistance of wading and swimming."

The work on shore, on islands which had been previously visited, was necessarily of a very varied character. A single illustration will suffice to give some idea of its general character:--

"In the afternoon the 'Southern Cross' was lying becalmed off Bauro, in San Cristoval, a lovely island in the Solomons group. . . . . First we went to Iri's boat-house, where we saw three new canoes, all of exquisite workmanship, inlaid with mother-o'-pearl, about forty feet long. . . . . Then we went to Iri's house, the council hall, long, low, and open at both ends, along the ridgepole were fastened twenty-seven skulls, two but recently placed there, and not yet darkened with smoke. There we sat down, and the Bishop, who had brought his book of their language on shore, talked to them, and give almost a little lecture in this Golgotha, alluding plainly to such unsightly ornaments, and saying that the great God hated wars, and fighting, and all such customs. . . . The people crowded to the beach to see them off: Iri walking up to his waist in the water."

During the long and constant voyages, which the plan of the Mission involved, the time was as regularly occupied as on shore:--

"The hold of the Mission-schooner was fitted up as a school-room, all our [19/20] hammocks being taken down; and here the Bishop and his fellow-workers kept school at regular hours, occupying the time and thoughts of their charges as on shore."

We must next try to imagine the Bishop engaged in the various occupations incident to his work, first at Auckland and afterwards at Norfolk Island:--

"The Bishop, with pen in hand and ear intent, begins his questions to a group seated on the floor. First may come a set of Sesake lads, who will divulge very little of and about their mother tongue, and making it a matter of hard pumping to get at anything. To this party a printer will enter with a proof-sheet of some other dialect, and the Sesake men go to sleep and rest their brains. By-and-bye a Mota set appears, and these, too, are quiet and silent, not to say dull. Now and then a meaning is given, or a word used which seems to let in a ray of philological light upon the researches into other tongues, to have affinities, to open out vistas, which it is quite cheering to follow. The unlearned companion listens with admiring but ignorant attention to the hunting-down of a word-- a prefix or an affix, as it may be--up Polynesia, down Melanesia, till it comes to earth in Malay, and there it is left, en pays de connaissance, for future consideration.

"The Bishop takes his full share from morning till night, not, indeed, the actual teaching in the school, but elementary and more advanced teaching in things divine, according to the capacity of each class. Then, too, he has the constant teaching of the teachers, with the endeavour to make them, in some degree, masters of the principle of language, on the acquisition of which so much of their future usefulness depends. He has also daily readings with the young students, who are in different stages of knowledge.

"After evening school, the Bishop, his clergy, and his aides, retire mostly to their own rooms. Then quietly or shyly, on this night or the other, one or two, three or four of the more intelligent of the black boys steal silently up to the Bishop's side, and by fits and starts, slowly, often painfully, tell their feelings, state their difficulties, ask for help, and I believe, with God's blessing, rarely fail to find it."

Here again is a sketch, from the Bishop's own pen, of the scene in the school:--

"Come into the hall" (he says); "they are all at school there now. What do you expect to find? Wild-looking fellows, nosy and unruly? Well, it is true they come from a wild race, that they are familiar with scenes you would shudder to hear of. But what do you see? Thirty young persons seated at four tables, from nine to ten to twenty-four years old. Some are writing, others summing: 'Four cocoa-nuts for three fish-hooks, how many for fifteen fishhooks?' &c., &c.; others are spelling away, somewhat laboriously, at the first sheet ever written in their language. Well, seven months ago no one on their island had ever worn a stitch of clothing; and that patient, rather rough-looking fellow, can show many scars received in warfare. . . . Who is that older-looking man, sitting with two lads and a young girl at that table? 'He is Wadrokal, our oldest scholar; this is the tenth year since Bishop Selwyn first brought him from his island, and he is teaching his little wife and two of his countrymen.' Others, with bright intelligent eye and thoughtful look, are learning the Catechism; some of them are very satisfactory candidates for Baptism; they are taught such Old Testament histories as bear most on the New Testament, and the gradual unfolding of the great Promise concerning the [20/21] 'seed of the woman;' and they grasp such teaching wonderfully! Some of them are 'very clear-headed fellows,' most of them very docile and lovable. If you come in the evening, you will be most of all pleased to see these young people teaching their own friends, the less advanced scholars. We are all astonished to find them so apt to teach; this is the most hopeful sign of all--no more loose talk, but catechizing, explaining, and then questioning out of the boys what has been explained."

The chief events which have marked the ten years of Bishop Patteson's episcopate can only be very briefly alluded to.

In 1863, a terrible disease in the form of a violent dysentery broke out in the College at Auckland. Fifty out of fifty-two scholars were attacked, and at one time it seemed as if none could survive. Their sufferings, though borne with singular patience, were terrible. The dining-hall was now changed into an hospital, and the Bishop into the head nurse and doctor; "night and day he nursed them--no task was too mean for him--washing and cleaning the poor fellows, making poultices, mixing medicines; he lent a hand at all." All but six of the patients happily recovered, but the same disease re-appearing a few months later, six more fell victims to it. To the Bishop it was a time of especial trial and responsibility. "I can," he writes, "thanks be to God, fully believe that this is a dispensation of mercy; HE loves them--oh, how far better than I do! . . . Often we had thought that some trial must come soon, and God sent it in the most merciful way. We may be tried--He only knows--by the far more bitter sorrow of seeing old scholars fall away, and the early faith of young converts grow cold. The trial--and it is a heavy one--has been given in the way in which we could best bear it now."

But a trial harder still to bear was to fall upon the Mission during the next year.

Several visits had been paid on former occasions to Santa Cruz, a large and very fine island. The people had a bad reputation, and generally came off to the ship in too large numbers to make it possible to hold much intercourse with them. They were a fine and warlike race, armed with bows and clubs, and wearing the unusual armlets and necklaces, and strips of a kind of cloth made of reeds closely woven, and having their hair plastered white with coral dust. After several visits friendly relations had been established, and a landing safely effected a seven different places. In 1864 the Bishop again visited the island. Not wishing to risk any life but his own, he left the boat in charge of Mr. Atkin and two of the Pitcairners--Edwin Nobbs, a son of the clergyman of the settlement, and Fisher Young, a lad of about 17--and swam ashore alone. He had spent some time amongst the people at a village some distance inland, and it was only when he had reached the boat safely, that a volley of arrows was fired at them from a body of some 300 natives, who stood on the coral reef which he had just left. Fisher [21/22] Young and Edwin Nobbs were both struck, one in the wrist and the other in the cheek. After lingering in great suffering for some days both died of tetanus, and were buried at sea.

It is needless to say how great a sorrow this event proved to the Bishop. He never seemed wholly to recover from it, and from this time forward, though the "remarkable serenity" which had always characterized him was deepened, he seemed to have lost much of his former mirthfulness and buoyancy.

In 1867 the head-quarters of the Mission was removed to Norfolk Island, where an estate of about 1,000 acres was granted on the opposite side to that already occupied by the Pitcairners. Here a group of Mission-buildings quickly sprang up, including a chapel, a large dining hall, rooms for the Bishop and clergy, and cottages for a few native married couples.

Early in 1870 the health of the Bishop was such as to cause serious uneasiness. He was attacked with violent internal inflammation, and for some time his life seemed to be in danger. On his partial recovery--due to the great skill and care with which he was treated by the Rev. Mr. Nobbs--it was arranged that he should go to Auckland to be under regular medical advice. Here he slowly recovered, and by the end of October was enabled to resume his usual duties.

In the meantime the Mission had continued to make steady progress. Two students of St. Augustine's had joined the Mission and been ordained. As many as 160 Melanesians might be seen dining together in the "new hall" at Norfolk Island, whilst from all the islands where old scholars had been settled the most encouraging accounts were brought. The Bishop writes in his last report, "They were all, thank God! preserved from falling away into evil, and, with only three or four exceptions, were actively engaged in doing good. Their life at the station at Mota, the daily morning and evening prayers and hymns at Ava [sic], their conversations with their relatives and friends, are producing good effects, and there was no instance of any scholar disgracing his Christian profession." The first ordained native clergyman, the Rev. George Sarawia, was also making good progress amongst his own people at Mota, and preparing the way for the general movement towards Christianity, recorded by the Bishop in his latest letters, and which seemed to him to justify his baptizing no fewer than ninety-seven children, "the whole Christian population being present as witnesses and sponsors."

For some time the Bishop had felt the gravest anxiety about the working of the so-called Polynesian Emigrant scheme. Only too well grounded, alas! were his anticipations of the result of the indiscriminating revenge likely to follow deceptions and atrocities practised by the traders. Letters received only a short time back from one of the clergy who had been staying in the islands, told of five shipwrecked men who [22/23] had been entertained most hospitably by the natives until an outrage committed in a neighbouring island led to their being all murdered in revenge!

In the midst of the grief and dismay caused by the news of the Bishop's death, we are in danger of forgetting the companion who, with equal self-devotion, has so often shared and at last met death at his side. The Rev. Joseph Atkin was educated at St. John's College, Auckland, and after being for some years previously attached to the Mission, was admitted to priest's orders on the Sunday before Christmas, 1869. The terms of respect and affection in which he was spoken of by all who were brought into contact with him, bear sad testimony to the great additional loss to the Mission staff which his death will occasion.

The management of the Mission, until a successor to the see be appointed, will, we imagine, devolve upon the Rev. R. H. Codrington, a Fellow of Wadham, and for many years a most valued honorary worker with the Bishop.

Of the sorrow, and possibly the discouragement, which these events will cause, we do not attempt to speak. We can only end as we began, by reminding ourselves that this laying down of life at the call of love and duty was a deliberate act. That such a sacrifice will have been made in vain, or that, for their own sakes, they are to be sorrowed that made it, we cannot think.

"Verily, verily, I say unto you, except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone; but if it die it bringeth forth much fruit. He that loveth his life shall lose it, and he that hateth his life in this world shall keep it unto life eternal. If any man serve me, let him follow me, and where I am there there shall also my servant be; if any man serve me, him will my Father honour" (John xxi. 24-26).

P.S.--The portrait which accompanies this paper having been submitted to the Bishop of Lichfield, he kindly writes: "The engraving of my dear friend is a strong but not pleasing likeness. We have other photographs of him which we like better, but not, perhaps, so expressive of the countenance with which he may be conceived to be thinking over the increasing difficulties and dangers placed in his path by the lawless traders. At the present season it rather commends itself to me."