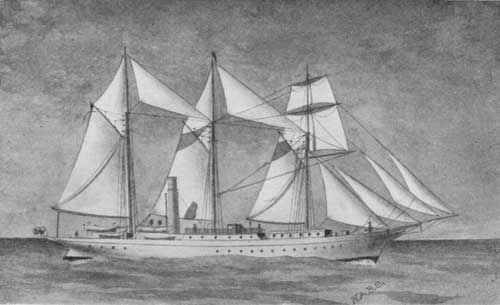

THE Melanesian Mission is now rather more than half a century old, and it certainly has entered on a second stage of existence. Perhaps, though there are still whole islands heathen and untouched, we may think of it as a branch of the Church Catholic rather than as merely a Mission now. It is more humdrum than it used to be; not less difficult, but with rather a different set of difficulties. Much of the old romance of savagery is gone. Many of the islands have as much forgotten the art of building war canoes as the people of Bugotu have that of tree-house building, and a great deal of the isolation of island life is gone also.

With an English Commissioner in Florida it is a necessary consequence that some sort of mail should find its way at stated intervals to the Solomon Islands, and the mail that brings letters to one person can easily be made to bring them to another. Accordingly we find that there are ways of hearing from, or getting to, England via Australia, and letters and telegrams reach missionaries in the islands themselves in this way; not only via Norfolk Island (itself very difficult of access) as used to be the case. And Norfolk Island has now a telegraphic cable laid, connecting it with the rest of the world, so that the most important of the news from the outside world reaches it in a few days at most.

Another change is denoted by the trifling fact that there is a great demand arising for spectacles in Melanesia. In itself it is a very small matter; but what it shows is that the Melanesian "Boys" of Bishop Patteson's time are elderly men now. Of course there were plenty of elderly men in Melanesia fifty years ago, but they needed no spectacles, as they never read or wrote, as our teachers must do.

We have spoken sadly of the end of the life of one of the earliest Melanesian priests. But Joy is stronger than sorrow, and there is another picture which may fittingly end this sketch--the life story of the individual Melanesian who most embodies all that this half century has brought to the islands.

It was in 1857 that a boy called Sarawia came on board the Southern Cross at Vanua Lava and made acquaintance with Bishop George Selwyn, and next year he paid a visit to New Zealand, where the school then was, although it was not till five years later that he was baptized, taking the name of George, after the Bishop of New Zealand. His exact age is not known, but he had a wife already when he joined the [134/135] Mission, so he must have been as much as sixteen forty-four years ago, and possibly a good deal more. He was connected by family ties with several of the Banks Islands, though, as time went on, he identified himself with Mota. It was chiefly owing to him and his brothers, Wogale and Woleg, being the most promising set of scholars in the early school, that Mota became the common tongue used in it.

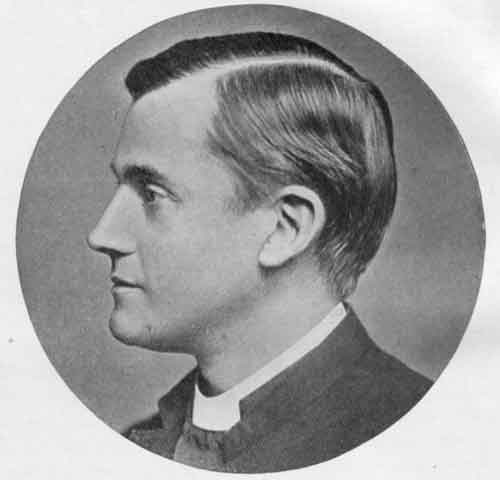

Third Bishop of Melanesia, 1894.

(From a Photograph by Russell & Sons.)

Belonging, as George Sarawia did, to several islands, not only to one, he did not feel the acute jealousy which so many have of any island except the one where they themselves live, and this made him an element of peace and impartiality. He was not a very clever man, but eminently loveable and trustworthy, "dear old George" to all the white staff, though they sometimes wished he would be a little more active, and more able to take in fresh ideas. But there never was the shadow of any scandal connected with him during all the years he was prominently known to the Mission, and he was a father to his large parish in Mota which felt his death deeply when he [135/136] passed away in August, 1901. He has left us an account of his first impressions of the white man as boyhood understood it.

"This is the story of my first acquaintance with white men when I went first with Bishops Selwyn and Patteson. No one from our islands up to this time had seen or been with white men, and they were very shy of them, thinking they were not men but ghosts or spirits.

"When I was a small boy I had not seen a big ship or a white man, but I saw them first the year the Bishop came to Port Patteson, in Vanua Lava. My home was in that harbour. They had anchored in the evening, and in the morning I paddled in my canoe near the big ship to buy something from them. When I came near the ship I saw Bishop Selwyn standing at the side, but I feared him for he wore a black coat, and his face was very white. He beckoned me to come on board, but I was still afraid and would not at first. I was about to pull ashore, but he continued beckoning me, for he did not know the Mota language. Then Bishop Patteson came, and they both tried to entice me, and I thought 'Why do they want me to go to them?' for I did not know them. I was ignorant, and thought they were, like the people of our islands, only wanting to deceive and kill me. Then I took courage and determined to go on board. I pulled close to the vessel's side and Bishop Selwyn threw me a rope with which to make fast my canoe. Then he gave me his hand and helped me on board. I saw that they received me kindly. They took me to the stern of the ship and we sat down. They asked me the names of the place and of the men, and wrote them. I did not understand their writing in the book, and looked at the feet of all on the ship, and I thought it was their own feet I saw, and I said, 'These men are partly iron,' and my bones shook like an earthquake. But it was leather that covered their feet.

"When I looked at the ship it seemed to me as large as the land; and I thought it was made by a spirit. And another thing amazed me, for I did not see the cable that made it fast--why did it not drift ashore? I thought the ship was like a man, that would move or stay where it was told, and I supposed it had been told to stay where it was. After this they let me go, seeing I was afraid to stay on board. I told the people about those on board, that they were kind men. I liked them both. Afterwards they pulled ashore in their boat, and they gave the men presents of axes. The Bishop kept me in the boat, and we sailed on board the ship. My father was much troubled about me lest the white men should eat me.* [Footnote: * Banks Islanders are not cannibals, but thought the mysterious white visitors capable of anything.] We all had mistaken thoughts about the white men. We thought they were our own men who had died and come to life in another land.

"The Bishop took six of us to sleep on board, but we did not understand that, and when we reached the ship the sun had set, but they would not let us go, and we thought that now indeed we should be eaten.

[137] "From the very first they were kind. They gave us presents of beads, hooks, and cloth, and fed us. We did not understand what kind of food a biscuit was, and did not eat it till we saw the white men eat it. They rang the bell for prayers. It was the first time we had heard the sound of a bell, and we did not know what it was. The Bishop told us to go below into the inside of the ship. We did not understand what for, but we went. We all six stared at them, and wondered what they were going to do. They began to sing a hymn, and we looked at each other very much frightened, and wanted to run out, but could not because we were below; so we sat in great fear. I saw them kneel down to pray. I did not know what prayer was; when I saw the Bishop read the prayer I thought he was only talking, and I sat down as at any ordinary thing. I heard them all say 'Amen.' I made three or four attempts to run out, but the Bishop kept me down with a motion of his hand, till at last I rushed out, intending to swim on shore. This is what I thought: that the chief men were ordering the others to kill us, and that they were consenting to it with the 'Amen.' When prayers were over, Bishop Patteson followed me on deck and brought me down below, and they took us into their own cabin in the stern, and I saw they did not despise us, but placed us on their own bunks and talked to us, and they gave orders to another man, who brought us new blankets to sleep in. I saw that before going to bed they changed their clothes, and then knelt for some time, and then went to sleep. They did the same in the morning, but because I was ignorant I did not understand it.

"They stayed in our harbour three days, and then they went away. One man gave orders to the other men about the sails, but I quite thought he was speaking to the ship, telling it to sail out of harbour. She sailed out quite straight.

"In those times we lived in great ignorance. If we killed anyone with a club, or shot anyone, or stole, we did not know it was wrong. We lived at enmity with one another, continually fighting, in fear always. And we had no clothes of any kind, but we were not ashamed.

"Now I will tell about their second coming to us. At the end of the eighth month the ship returned. I went in my canoe alongside the ship, and Bishop Selwyn called me by name and said, 'If you had gone with me to New Zealand you would have returned. to-day.' I said nothing, but I thought: 'These are good men, they do not deceive people.'

"The next day the Bishop went ashore. We were all assembled on the shore--my father, mother, brothers, and others, and the Bishop sat in the midst of us and talked. He soon said to me, 'Do you wish to go with me?' I answered, 'I do not know.' Then he said, 'I will bring you back in four months.' They continued asking me, and at last I consented, and they asked my father and he consented, but with some fear lest I should be taken quite away and not return. So five of us went on board the ship and slept there that we might go with the Bishop, and in the morning the [137/138] canoes came and tried to get us back, and our elder brothers cried to the Bishop to let us go, but he would not. He said, 'They shall come back in four months.' They returned ashore very sorrowful and wept.

"When we were outside the harbour some of us were frightened and jumped into the sea and swam ashore, but two of us remained. I had made up my mind to go with them because they said they would bring me back in four months, and I had seen already that their words and deeds agreed. I knew they would bring me back.

"My thoughts when I first went with the Bishop were that I would go to where everything began and collect for myself axes and knives, and hooks and clothes, and bring back a great quantity with me. I did not go for any other reason."

The Southern Cross was then on its way north and visited the Solomon Islands, and called at various places. After a time Bishop Patteson tried to teach the boys their letters, and Sarawia was impressed and noticed various things, but chiefly with mere curiosity as he considers.

At the appointed time the two boys were returned to their homes, and the relations crowded round to ask whether the white men had been good to them, upon which Sarawia gave them an excellent character for having "fed them, and never been angry or struck them," and persuaded his father to let him have a pig and some yams to give to the Bishop as a present.

He continues, "I told my people about the other islands I had seen but they knew nothing about. We only knew of six islands, and we thought that there were no others. We saw some of the white people in the ship, and they had red shirts, and we thought that perhaps they lived where the sun begins, for we see the sun red when it rises, and when it sets, and we thought that these men had made their clothes red with dye from the sun.

"When I returned from that journey I stayed at home two or three years. There was fighting and I joined in it. We killed men in the fight. I saw no harm in it; I thought it was good; a sign that I was still unenlightened."

Such was Sarawia in 1858, and no doubt he has given us a very good idea of the way the average Melanesian looked upon the first visits of the missionaries. The fight he refers to was in defence of his district of Vanua Lava, and during his stay at home he built himself a house with two stories, and marked it with a cross, before he himself was a Christian.

He was one of the two Banks Islanders baptized in 1863, and two years later he once more led the way, with one other, to be confirmed and to be the first Melanesian Communicants. Three years later again he was the first deacon, and was ordained priest just ten years from the time of his baptism, and fifteen years from the days when he went on board the Southern Cross and rushed out from prayers for fear of being eaten. The entire change from the wild, naked boy to the civilized clergyman [138/139] who upheld the spirit of his people in the first shock of their Bishop's murder is very striking.

Since that, thirty years have passed, and George has been still at Mota, and itinerating amongst the islands near, to administer the Holy Communion where there was no other priest. He was not in very good health for a great many years past, often crippled with rheumatism, but he managed to be active in visiting and teaching, and diligent in composing strife.

Such was the quiet life of the first Melanesian convert until the end, when, though more ailing than usual, he made the effort to go to church on Sunday, August 4th, to speak to the people about preparing for the Bishop's visit, but on his return from church he had to take to his bed, and only once left it again. On the Wednesday he called all his people together, and urged them to show diligence in right doing. On Thursday he again struggled into church to receive back a penitent, and got back to his bed in a state of exhaustion. He felt and said that unless the Bishop came [139/140] next day they should not meet here; and it proved true; he died on the Sunday, August 11th, 1901.

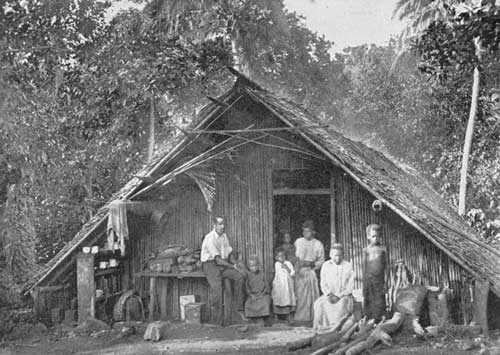

With his widow, son, grandchildren, and son's wife.

On hearing of his illness the Southern Cross hastened to Mota, but when near enough to see details they saw a black flag waving from the landing-place, and understood the signal. Three men only, instead of the usual cheery crowd, were awaiting them on the beach, and behind the three silent figures was a black-board with the news they had no heart to speak, written upon it: "George died last Sunday, August 11th." The three messengers were the Rev. Robert Pantutun (who, happily, was in Mota at the time), his son-in-law and George's son, Simon Sarawia, and one other.

All Mota had come together to bury him, and many were still in the village when the Southern Cross arrived, bringing the Bishop and other friends, whom it was a great comfort to have even four days after, sorry as they were not to have come in time.

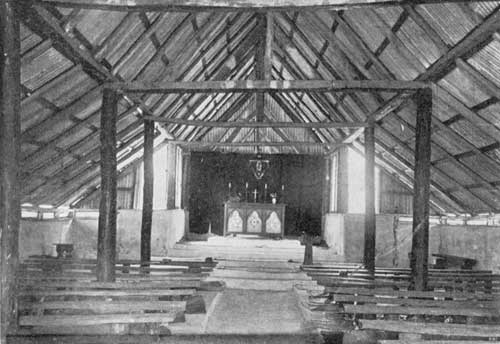

[141] "The hearts of all the people were wrung by George's death," writes one of the party." We held a service over his grave, which is made by the side of the almost finished new church, in the open space of the village.

"The new church and grave will be George's monument, if monuments are needed for a man whose consistently good life as deacon and priest for thirty-three years never once failed, or even seemed to swerve. Dear old George, so simple and cheery, is gone. Shall we ever look upon his like again?"

Surely even to those who miss him most the chief feeling must be of thankfulness that God has allowed the first-fruits of Melanesia's native ministry to live so signally unspotted a life and pass so peacefully to the grave in hopes of a joyful resurrection.

We have lingered lovingly over this particular story, not because it is very remarkable, but because it is very typical.

In some ways the more gifted individuals are, the less the thought of them helps the general mass. Everybody cannot be a genius, but everyone can be good, and by living a simple Christian life in that state to which it has pleased God to call them, many of our Melanesian men and women are doing much to help their neighbours and glorify their Father in heaven.

Looking back on these fifty-four years in Melanesia the refrain of all our thoughts is, thank God that he has sent His servants to bring the knowledge of His Light to the islands, and "to guide their feet in the way of Peace."

"The Religion of Peace" the islanders call Christianity. They contrast it with the days when every village was at war with its neighbours, and every family had its blood feud. But there is a deeper peace than this outward one which it has brought to many a soul. The peace of God, which passeth all understanding; the peace which our Lord gave to His disciples when He came to them walking on the sea, and said, "Peace be unto you." May that peace abide for ever with those labouring for Him in the Isles of the Sea.