A STRETCH of many miles of sea separates the Santa Cruz and Torres Island Groups. The Torres Islands are five in number, and lie in a straight line, one to the south of the other. One of them, which is quite tiny, is uninhabited, the other four are insignificant in size, the largest being only about seven miles long by four miles broad. But they are of more importance than their geographical size would lead us to think them, as the spirit that prevails there is as good as we find anywhere amongst the Melanesian Christians.

Edward Wogale, the cleverest of the brother teachers from Mota, was the first Deacon stationed here. He took up his abode on the Island of Loh when he returned from doing most useful teaching work amongst the labourers in Fiji, and the rest of his life was given up to the Torres Islands. Indeed, he may be said to have given himself not only to but for them, for he died of the climate, or whatever it is that makes this group exceptionally unhealthy. It is not, perhaps, all the fault of the climate, as the burial, or rather non-burial, customs are what we should consider most dangerous, and likely to poison earth and air for many generations. There is a dislike to burying the dead out of sight in these islands, particularly people of any sort of rank. They were laid on platforms in the middle of the villages, and there kept till the process of putrefaction was completed, when the remains were removed to a small enclosure surrounded by a stone wall. When completely dried, the bones suitable for the purpose were taken to form arrow heads. The arrows are beautifully made, and the bone tips are from 4 to 12 inches in length. Like all Melanesian arrows they have no feathers. On account, therefore, of the use to which they put the bones, and also because the exposure was accompanied by elaborate ceremonies doing honour to the dead, the native feeling shuddered at the idea of putting their friends' remains, as they expressed it, "in a mere field." It seemed to them painful and disrespectful, and Christianity, with its reasonable care for the body, has had a very hard fight with prejudice in the matter. And of course it is a matter to be very careful how they interfere with, for, though dangerous to health, the custom of keeping their beloved dead unburied in their very midst is not a sin.

Probably this poisonous custom was the original cause of the prevalent form of disease there, a sort of very virulent ulcer, of which, if neglected, people often die in [118/119] a few days. And although it was most painful, people were so used to it that they seldom took proper care, wading into the salt sea with open sores on their legs, although they had been repeatedly warned it would make them much worse. Of course, careful and constant bathing and washing rags with fresh water was essential, and about this they were careless, for it was really difficult to get fresh water, except, of course, rain water, which is not always to be had, although there is a great deal too much sometimes.

There are hardly any streams in the Torres Islands, and the natives drink cocoanut "milk" when water is scarce, but of course they cannot wash in that, so they either bathe in the sea or go without washing at all.

Besides these islands being so unhealthy, the natives used to be very fierce and quarrelsome. In 1880 it was reported that in Tegua there were twenty-five villages with each about thirty inhabitants, and every village was jealous of all the rest, and fiercely resented any other village being visited or noticed in any way.

It was three years after that that Edward Wogale died in Loh. The people had done their best for him, and took great care of his wife and children till the Southern Cross returned and took them home to Mota. Then another Mota Deacon, Robert Pantutun, came to the help of the Torres people.

He married a wife from the group, so he was very much at home there. The Torres group of islands has suffered even more than others from the labour vessels, and poor Robert had a very trying experience once. He had a good large class of lads who were preparing for baptism, and who were getting on nicely, when a vessel was seen off the coast, and naturally the boys went down to the shore to see what she was like. They only meant to look at her, but the desire to see the world overcame one of them, and he impulsively jumped into the boat that was recruiting, and the whole class followed his example, to the great distress of their teacher and the loss of their island in many ways. Yet even this is not quite so bad as the habit some labour vessels indulge in of taking women. That women should wish to see the world as well as men is natural enough, but almost every woman in Melanesia is either betrothed or married at a very early age, and has therefore no right to go away. It would matter far less if traders enlisted men and their wives together, but they do not trouble to find out about such things; they take anyone who offers herself, and therefore a discontented daughter or a woman who is tired of her husband, or has quarrelled with him, will go down to the vessel and away to Fiji or Queensland for years, leaving her duties and her husband to get on as they may without her. Amongst the heathen in such a case a man or woman who was deserted would be free to marry again, but a Christian is in a very hard case, for he cannot do so; consequently the harm done by recruiting women and girls is manifest, and often has most disastrous consequences. But there are very bright lights even on the labour question. For instance, a native of Tegua who had attended a Sunday School at the plantation where [119/121] he had worked in Queensland, was anxious on his return home to start a school on his own island. He was told that before he could do this he must go to Loh, where there was a class of candidates for baptism, and be taught with them. If he could do this, then when the Southern Cross returned he could be baptized with the rest. It happened to be the very busiest time of the year, and he could be ill spared from his gardens, and this was pointed out to him. Still he persisted. "Take me and teach me. I must help here." "But what about your gardens?" "My wife will look after those; she is a good worker." "And who will look after your wife?" He paused. "Yes, I don't like leaving her, but," he paused again, "I think God will look after her. Do you think He will?" And thus he went in faith to the next island, returning in course of time a Christian, and able to take up work amongst his own people.

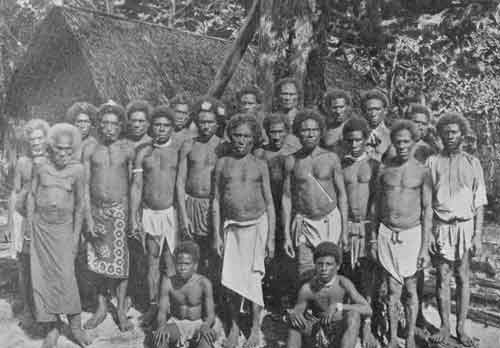

(From a Photograph by Rev. L. P. Robin.)

All these more southerly groups of islands are under a sort of bondage to secret societies, which they call Huqë in some places, and which are much the same, under different names, wherever they are found. "Everybody who is anybody "belongs to the Huqë, and a person who does not is looked upon as no gentleman; "a Bounder" in fact--quite outside the bounds of good society. They enter the boys into these societies at a very early age, and buy them their steps up until they reach the highest rank, when they are very great men indeed, and much looked up to in their island. The entrance examination, if we may so call it, is apparently a sort of ordeal to prove their courage. They have to do a great many very disagreeable things, such as having to rush through long sort of thickets of stinging plants, being beaten with burning sticks so as to brand them, given very little food and that nasty, and various other trials of endurance. They also dress up in queer costumes with masks made of leaves, dance about and make mysterious noises, which those not in the secret ascribe to ghosts, and indulge in a great deal of rough horse-play. But all this, though tiresome, is not wrong, and it would not matter very much if it were not that they greatly hinder prayers and school by suddenly tabooing half the roads on an island, so that the people have to go a long way round, and really often cannot spare the time to come regularly. The places where all the mysteries centre are spots well hidden in the woods called Salagoro, and here people have to remain sometimes for a month at a time, all their work being stopped. In the heathen eyes there was nothing more important than these societies, and therefore to make all the rest of life give way to them was a natural thing. But such members of the society as have become Christians know that there are a great many things of more importance, and it is here the conflict of duties makes itself felt. And besides all we have mentioned, there are rules about food which, especially in the Torres Islands, where the society is extra strict, make it impossible for Christians to belong to the Salagoro. Nobody must eat with women or with any man of a lower grade in the Huqë than himself. If he did such a thing he lost rank himself, and his neighbours despised him.

[122] But of course Christians have very often to make up their minds to do things for which their neighbours will despise them, just as in early days of Christianity the Greeks thought the Cross foolishness, and Mr. Robin, who was in charge of the Torres Island work, felt himself bound to make converts understand that on their baptism they must renounce as contrary to Christian brotherhood the exclusive rules of the Huqë. That they are contrary to the spirit of Christian equality we see at a glance, but very likely the people themselves do not see this very readily, because they do not exactly touch the question of baptism. But of course nobody can be accepted who only means to go a little way in Christian paths and hopes to stop short when he comes to something he does not like, and nobody could be admitted to the Holy Communion, to which all teaching leads, who would not eat with those of lower rank than himself. This made it very hard for men of any position to come forward in the Torres Islands. The man who broke the rules of the society was looked upon as a low fellow, and compared to a flying fox, which is a sort of bat, neither properly bird nor beast. The few men who reached the highest rank in the Huqë, who had a right to eat in the last and most honourable compartment of the Gamal, and who cooked their meals at the highest oven, were very great men indeed, and very much looked up to, and it was humbling themselves to the dust to give it all up and receive baptism. It was a sort of thing no one could do without the grace of God, to shew him what the spiritual gain was which made it richly worth while.

For a long time nobody seemed willing to come forward at all. However, in the first year the Mission was really settled amongst them, seven did make the sacrifice, and one of these was of the second rank, but of the four men in the first rank no one seemed likely to do so.

Three of them were very old, and never took any interest in Christian teaching, but the fourth, Tëqalqal, who was the principal chief at Tëgua, felt differently. He was friendly, and he listened, but he could not for a long time make up his mind to go beyond listening. His old brothers in the first rank all died, and other men did not press up from the ranks below as they would have done formerly, but still the Huqë in his place was kept up by Tëqalqal in the first rank and about forty men of the second, third, and fourth ranks. When it was found that some were willing to throw up the Huqë, the people said, "It is not fitting that a position which has been gained with great difficulty and in a long time should be thrown up as nothing," and they made, therefore, a rule that any desiring to do so must descend as they had risen, oven by oven, till they reached the lowest. This made it much harder, and so when Tëqalqal at last made up his mind to "eat his way down," as it is called, it could not be got over quickly. He must be under the observation of his neighbours, day after day, the subject of the village gossip, and very disagreeable it must have been.

[124] At last, however, he made his resolution. He left the place of honour in the Gamal which had been his for so long, and went and ate that day in the section below it with the men of the second rank. Next day Tëqalqal and the men of the second rank, who were also eating themselves out, ate in the third division, and the day after all three grades ate together in the fourth, and so on, until in this way they reached the common space near the door, where the little boys sit who are as yet uninitiated. Last of all came a great feast out of doors, in which even the women joined and ate with the men. After all was over they got up and gave a great shout, going off into a succession of Torres Island whoops; a most weird and piercing sound, which it appears to give them very great pleasure to emit.

Mr. Robin, who shared Tëqalqal's last Gamal meal, says: "Truly it was most awe-inspiring, for one seemed to feel the breath of God upon one and to hear the still, small Voice speaking to the heart of the man and his friends. What else could have inspired them to humble themselves down to the ground before their people and amidst their scoffs and sneers? And there was more than the mere setting aside of rank. The chief is considered sacred, and his people begged him for their sake as well as his own not to do this thing, lest they should all suffer for it. But he led on in faith, and many others took courage and followed him."

Besides the Huqë customs there is another difficulty in the Torres Isles in the curious and wicked habit of charming away the lives of enemies, which has to be renounced by all baptized Christians. It is a way of getting rid of or injuring people by spells without touching them, not unlike the old witchcraft customs of Europe. It is certainly murder and hatred in intention, and though it is impossible to see how, it does seem as if the powers of evil had something to do with it, for the man who is thus "charmed" does very often suffer in a way which is quite inexplicable. There is no doubt the practice is wicked, and this is a thing the people readily understand. It is quite given up now in Loh, where Christian teaching has been going on for more than twenty years, and the other islands are rapidly following Loh's example in the matter.

Loh had the first school, then Tëgua, as we have seen. Toga was anxious to follow, but it was hard to find so many teachers, and Toga did not possess any one man like the returned labourer who started the school at Tëgua.

These islanders do not build canoes; they go about on bamboo rafts like the one in the picture, which cannot move fast, even in fine weather, and dare not venture out at all in rough, so that though thee islands are not many miles apart, they cannot readily go from one to another to attend church or school.

In 1894-5 Mr. Robin spent Christmas in the group, making Loh his headquarters, but visiting the other islands also. A party of people from the northern and well-affected part of Toga came over to Loh whilst he was gone to give Tëgua its Christmas Services. "How they waited at Toga" we must tell in his own words:--

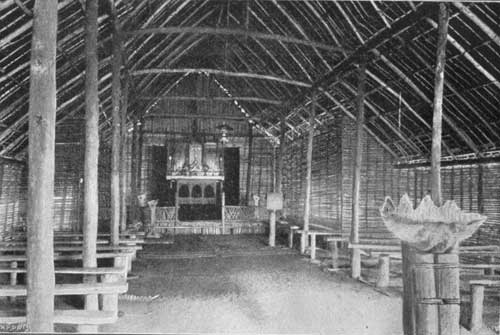

[125] "They had asked over and over again for a teacher in this northern part of Toga, and there was no teacher to send them, and at last they got tired of waiting, doing nothing. And it happened once that when I was at St. Cuthbert's, on Tëgua, the people of Loh, looking southwards across the sea towards Toga on a fine calm morning, saw the smoke of a fire on Toga. The position of the fire, and certain signals made by wafting the smoke away, told them that people were coming over from there to Loh. After a time a small black speck could be discerned far away on the sea, near to Toga, and this grew very slowly till they could see that a raft was being paddled across the passage between the two islands. Towards evening the raft arrived with its crew of some ten natives. They landed and stayed ten days, but they did not say what they had come for, and it was not polite to ask them. It was noticed, however, that they came to St. Aidan's every day at Matins and Evensong, and sat quietly outside the church listening to what was going on, and looking through the latticed sides of the building to see. And they asked many questions during their stay about the way life went on in the Christian village, and what things Christians did not do that others did. The day for their departure came at last, and [125/126] before they left, one of them told the teacher at St. Aidan's the reason of their visit. 'We are tired,' he said, 'of asking for a teacher, and no one comes; so we determined to come, and see for ourselves something of your way of living here in a place that has the new Teaching. Now we shall go back, and we shall leave off such and such things which you Christians have left off, and so we shall be getting ready for the teacher when he does come, and he won't have to waste time telling us of a lot of things we do wrong, but can start straight away and teach us this truth.' So they went off home again.

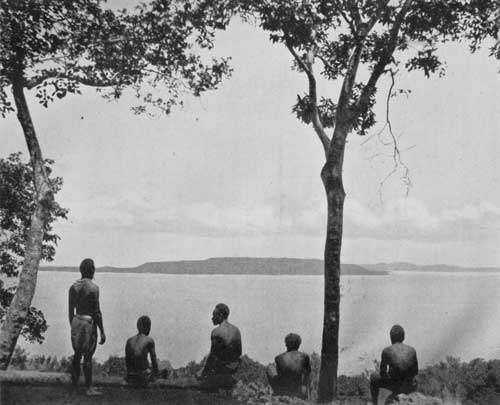

(From a Photograph by Rev. L. P.Robin.)

"A month or two afterwards I came back to St. Aidan's, and they told me the story of the Togans' visit. A few days after I went over to see them. They gave me a warm welcome, and conducted me with some pride to the place they told me I was to stay at. About two miles from the landing-place we emerged from the bush on to a plateau on the edge of a high cliff, from which one looked out over the passage between Toga and Loh. Here the ground had been cleared, fenced, and swept. In the middle of the clearing was a little hut, in which they invited me to make myself at home. I found, on enquiry, that they had already given up certain things which they had learnt were not right. But the most remarkable thing was that they had established a Sunday, or rather a Sabbath Day, and had made it their custom to assemble on this day at the clearing. They could not come every day because it was too far from their villages; but on the Sunday, at the time when they knew, by the sun, that Matins and Evensong were going on over the sea at Loh, they all sat perfectly quiet on the cliff. And so they seemed to wait and cry 'Come over and help us.'

"When I got back to Loh a day was fixed for special intercession for Toga, that their longing might be satisfied, their wordless prayers heard, and that someone might be sent to help them.

"About a fortnight after this, as I was sitting in my hut working at translations, between 11.0 and 12.0 at night, I heard footsteps outside. Presently two lads stole quietly in and sat themselves down on the floor. They were boys of about fifteen and sixteen years of age, and had both been to Norfolk Island once, but in each case their health had broken down, and they were unable to stay more than a very short time. They had both received Holy Baptism at Loh, and were, of course, still attending the school there. Well, there, they sat, and not a word did they say for a long time, and I wondered what they had come for, but knew I should hear if I waited, and did not ask questions. After about a quarter of an hour, one of the lads said, 'Father, have you got anyone yet for Toga?' 'No, my boy; there is no one yet for Toga.' Silence again for another ten minutes or so, and then out it came. 'Do you think Basil and I might go?' then, hurriedly, 'We know we aren't fit, we aren't proper teachers, and we are very ignorant; still we have been baptized and we can read and write. We might be able to do a little till a proper teacher comes.'

[128] And then it was my turn to be silent for a time, for I suddenly found that my voice had gone. Then I tried to put before them what it was that they proposed to do; the possible temptations and dangers (for by no means all the people at Toga wanted the Mission there, and some of those who did not want it had said some very impolite things as to their intentions if any teacher came to them), the certain home-sickness, etc. I told them to think it all over again, and pray about it, and to come to me again in three days. They came on the third day with just these words--'We are determined:'

"A week later I started off to take them in the boat to Toga. Just as we set off a northerly wind sprang up and stiffened rapidly into a strong breeze. We hoisted the sail, and were not long in crossing the passage, but the wind that had helped us on our way had also raised so heavy a surf at Toga that the boat could not be brought near the shore, where the great breakers were crashing on the coral rocks. To attempt to land would be madness, and I turned the head of the boat out to sea again and told the boys I would bring them over another day. But they said, 'We are here now, and we are not going back.' They scrambled over the thwarts, shook hands, said good-bye, and then jumped into the sea and swam through the surf to the shore. And that is how 'the Word' was brought to Toga."

Thus Toga got her teachers, and now Christianity is spreading all over her. At present Mr. Robin is working for the Mission in England, so there is not a white clergyman who can be spared for this small group, and they are under the charge of Simon Qalges, a. deacon, born in Motalava, who lives there and carries on the work between the visits of the Southern Cross.

We rejoice to read in 1901 that "the Bishop has just baptized thirty-five people on Toga, the first converts from there. Qalges is travelling about among the heathen on this island, and many have taken to eating with their families, the first step towards Christian social life. He has also stopped some fighting. On both Loh and Tëgua there have been confirmations of some fifty altogether." But there is much left to do, for out of a population of eight hundred not much more than half are yet Christians.