SAN CRISTOVAL, or, as the natives call it, Bauro, is a large island, some seventy miles long by twenty miles broad, lying to the south of Ulawa. It is still very savage in the interior, and still so addicted to cannibalism it is hard to make much way there.

Mr. Atkin worked here, and it was Stephen Taroaniara's island, where he had hoped to teach, but with their death ended the immediate hopes of Christianizing Bauro, and in the thirty years since that disastrous day sadly little progress has been made. There are but eight schools even now, and they are all near the coast. However, there are signs of awakening, and last year a fresh school was started at Borè by the request of its chief Ariahurono. It is on a very small scale; the pupils may be counted on the fingers, and the schoolroom is a small shed behind Ariahurono's house where he stores his copra. Still it is a beginning.

Ariahurono can speak a little English, and likes to air it. He said the other day, "My mamma, when I was born, she want no piccaninni (child), so she dig a hole and she put me in. But another woman she want piccaninni, so she take me out and feed me." Such unpleasant mammas are still only too common in the island, though probably it is the grandmammas who are chiefly to blame. Public opinion has not yet arrived at regarding the negative not allowing children to survive as the positive taking of life, and the elder women claim the right to limit the number of children whom the young and strong have to attend to. The old women have to do the field and garden work if the mothers are taken up with family cares, and this they think unfair. There is, however, a determined set being made now against infanticide, and the wives of teachers are made to realize their duties and opportunities in this respect, and by managing to see the babies at once have succeeded in saving many lives already. Strange to say, the children the natives keep they treat kindly, and are just as fond of them as other parents.

One of the oldest friends of the Mission in St. Cristoval is Taki, the chief of Wango, to whom Bishop Patteson paid a visit nearly forty years ago. He was a chief of the old type, princely in ideas, and with a certain nobility about him, but very much of a savage. His village is situated on a beautiful river, whose banks glow with scarlet hybiscus, and are fringed by sago and areca palms, nutmegs and other tropical trees.

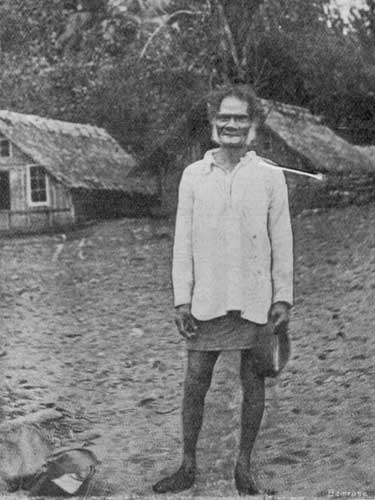

[108] Years ago when Taki first came on board the Southern Cross he clothed himself as a necessary courtesy, his full dress being a waistcoat. As we see he has got a little further than that now. His past history is better not enquired into too closely. He has had his share in head-hunting raids in his time, and when he presented an old and curious food-bowl to a visitor as a souvenir, the recipient felt he had better not think too much about what kind of food it might formerly have contained. But horrible as cannibalism seems to us, however we look at it, we make a mistake if we only take it as a sort of awful gluttony. To the islanders it probably was originally something very different from that. There is a tribe in Africa which eats lion's flesh that they may thereby grow as brave and strong as lions, and it is this sort of idea that prompted cannibalism originally. Men partook of their enemies in the hope of acquiring their qualities. Surely at the root of this sacramental idea, horribly distorted as it is, there is something which should greatly help them to grasp the meaning of the holiest of Christian services, and to see that they have to choose whether they will share the table of devils or the Table of the Lord.

Chief of Wango, San Cristoval.

[109] Twelve years ago Taki bought a new canoe, a splendid thing, thirty feet long, inlaid with mother of pearl, and altogether a triumph of building art. When he had secured it the old chief was in a difficulty, for it was a time-honoured custom to sacrifice a life on these occasions, and though still a heathen, Taki was too much under the influence of the new ideas to quite like to do this. Yet how could he in his old age forego the custom? His people came to the rescue, and offered to take the canoe for him from village to village, exhibiting it and collecting the usual presents, but only on condition that no life was taken. The chief consented, but was not hopeful that the venture would succeed. However, nothing could have done better; they had the most perfect weather and received the most satisfactory amount of presents, but in one way the expedition was a great novelty. San Cristoval was astonished to notice that Taki's state barge carried a chaplain, and its crew met regularly morning and evening to worship the Christian's God.

[110] Stephen Taroaniara left one little girl, Rosa, his only child. She was practically an orphan, his wife having turned out badly, so Rosa was brought up at Norfolk Island. Stephen was a man of consequence, and a marriage was arranged between Rosa and Taki's only son, Robert Jackson. It seemed most suitable, and great hopes were founded on it, which were doomed to disappointment. The young people were fond of each other, but Taki did not consider Rosa's education sufficient for his son. She could cook, sew, mend and make clothes, but she had not been taught to work in the fields, so Taki regarded her as a useless fine lady and refused to buy her for Robert's wife. The effect was bad on both young people. They drifted away, married heathens, and died. On Robert's first wife dying he married again a very nice woman who helped him to return to his Faith, and he was steadily improving when he had an accident, being so badly bitten by a shark that he died in consequence, having done little to help Wango to become Christian.

Taki himself was so much impressed by the blessings which had attended the Christian canoe party, that he put himself under teaching, and some five years later was baptized by the name of " John Still," after the missionary whose too short stay amongst them had left very pleasant memories in the Solomon Islands.