FLORIDA has many advantages over some other parts of Melanesia, but it has disadvantages too. It has suffered much through the bad example of some of the white traders.

There is a small island called Savo about half-way between Florida and the northern point of Guadalcanar, which is a trading centre, and this has affected both districts, though Guadalcanar has been the more seriously injured by it.

The scum of earth's wickedness is very apt to drift to such places, and the natives who come in contact with it are by no means the happy children of nature some people think all "untutored savages" must be. Where the dregs of old civilization mixes with the raw material of savage life, the result is a most appalling combination of disease and vice.

Of course all traders are not vicious. Some of those settled on the islands do good and no harm by their example of justice, businesslike ways, and respect for both men and women; but it is to be feared that this cannot be said of the majority.

The traders come for different things. Tortoise-shell, sandal wood, and mother of pearl, and several other products are to be found here, but the chief trade is in copra. This is cocoanut dried in a particular way, which is used in large quantities for soap, candles, and cooking, and in many other ways, so that there is always a demand for it.

In Bishop Patteson's days the evil chiefly felt was the carrying away of labourers to the plantations, by which the islands were depopulated. To a certain extent this evil still exists, but there is another aspect which years have developed, and that is the question. What will the labourers be like when they come home again?

There is a slight difference of opinion amongst the missionaries as to whether the labour traffic, if properly controlled, is altogether an evil. There is no harm in the Islanders wanting to see something beyond their own corner of the world, and it is very natural they should do so. And on a well managed plantation, either in Queensland or Fiji, they not merely get their ideas enlarged, but they sometimes get a certain amount of religious teaching.

There are schools and missionaries who do their best to ensure that the Melanesians' sojourn on the plantations and in the service of professing Christians shall not plunge them deeper into heathenism than when they left their island; but they are [86/87] scattered over so many plantations at a distance from one another that it is very hard to get at them during the short times they can call their own, and, moreover, they speak many different languages, which makes it difficult to give definite lessons. There is a sort of jargon, called pigeon English, which gets spoken on the plantations more or less by everybody, but it is a most ridiculous collection of slang words and figures of speech, in which it is by no means easy to give religious teaching without irreverence.

To the Melanesians the plantations are the tree of knowledge of good and evil, and when they return to their homes their teachers must always be anxious as to which element will predominate in them Some have come back having been baptized and intending to live as Christians, but when they get home to the old heathen surroundings and find their neighbours don't expect it of them, they sink back into their old habits; whilst some few come forward, joining hands with the Mission workers, whether white or black, and throw all the power they have gained into the treasury of Christianity. When they do this their help is invaluable. But there are others who return, having learnt chiefly that spirits are good to drink, and how to fire off a gun. And there is even a story of one returned labourer who, finding his enemy, invited him to a meal, professing to be reconciled to him, and killed him by putting poison into the food. The savages of his island cried shame on this very loudly, such treachery being hitherto unknown.

It is very hard indeed to give any idea of the contrasting darkness and light in the islands. The darkness is darker than anyone who is likely to read these words can conceive of. Heathenism from generation to generation is not only misbelief, as many are apt to fancy; it makes life evil, impure, and cruel and hopeless to an extent we can hardly realize who live in a country where even vice is kept within certain limits by laws and an external Christian standard settled for hundreds of years.

But if we cannot realize what the darkness they have lived in is, we can almost as little realize what the light is, which seems to burst on those who are really converted. The way in which they embrace and rejoice in God's love and Christ's salvation, and value their Christian privileges, is a revelation, and puts many of us to shame who have always heard the glad tidings. There are many men and women in Melanesia who do hunger and thirst after righteousness, and whose souls are most mercifully and wonderfully "filled" according to the promise. But we must not fancy that religion fills the whole thoughts of a Melanesian convert, though it undoubtedly influences his life much more than it does that of the ordinary Englishman. They have just as full a life as we have, though of a different kind, and the point of religion with them, as with us, is to make them live well, doing their duty in that state of life to which it has pleased God to call them; not to make Englishmen of them.

It is their business to be good Melanesians, and not to change their ways, except where those ways have been wrong in themselves. They have their yam gardens [87/88] to attend to, their cocoanut trees, their pigs, their boating, house building, and fishing. They have still to be always guarding themselves against surprise from their enemies, though there are many places now where life is very fairly safe, especially in Florida, and their minds are so undisciplined and so accustomed to passing through life in a leisurely way, and attending to the village opinions and gossip, that it is hard to get an entrance for holy things.

Bishop John, Selwyn found himself addressed as "Bishooka"--a combination of bishop and the fish-hooks to be obtained from him--which, he said, "ought to be a good title for a fisher of men," but which, nevertheless, showed the all-pervading trading instincts of the Islanders. As he once expressed it, "It is very hard to look upwards through yards of calico and dungaree, and it wants faith to lift one above the region of pipes and tobacco, yams and tomahawks, and to enable one to feel, as one rows to a reef in a blazing sun and is surrounded by an excited crowd thinking only of 'one more fish-hook,' we are working at the command of and under the eye of God, and that perhaps some small boy we buy with a fish-hook may be the means of turning his people to serve the true God."

But with all its disadvantages Florida is unquestionably more advanced and more thickly peopled by Christians than any other part of Melanesia, and with Christianity comes a longing for order; and law goes hand in hand with order, which accounts for that very remarkable change, the institution of the Vaukolu or native Parliament of the Floridas.

The Island Mission has always on principle ranged itself on the side of obedience to the native Government, and not superseded it. Even in their protests against the head-hunting and marriage customs of the chiefs, it was their way to make the native authorities themselves feel their responsibility as rulers to set a good example, and they have never attempted to ignore their jurisdiction. But as Christianity brought peace and civilization in its train, the natives felt more and more the advantages of law and order, and they turned to their missionary friends and asked their advice how to guide themselves into safe and settled ways of government; and this gave the opening for the Vaukolu. This was nothing more nor less than a sort of national assembly--a meeting of all the chiefs, and of a certain number of their people, to agree as to what was for their mutual good.

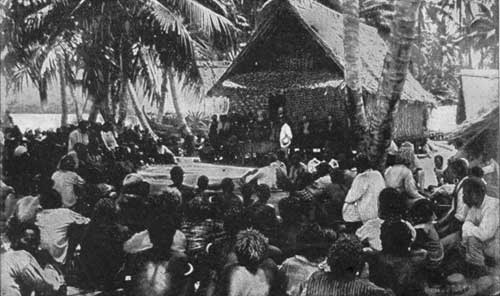

"My next piece of work," the Bishop writes in 1888, "was a very delightful one. Mr. Plant had fixed August 30th for his great meeting of chiefs and teachers at Belaga, and thither we went, picking up contingents here and there. On the way an incident showed the good of such meetings. Lipa, the great (still heathen) chief of Oleyuga, and Ellison Gura, our teacher at the neighbouring station of Ravu, had, through go-betweens, had a long and wordy dispute about a piece of land which both claimed. Messages had not been given, sayings, when repeated, had appeared to be threats, and altogether Lipa had been afraid to come to us lest we should overawe him into an [88/89] arrangement he did not approve of. But when he and Gura met on their way to the Parliament, they discovered in a few minutes' chat that they were both seeking the same thing. Neither wanted the land for himself, but each had been tambuing it to preserve it for the heirs of the rightful owner.

"September 1st was a very great day. It began with Holy Communion, at which nearly all our teachers were present. I hardly knew what I prayed for definitely; it seemed as if my whole heart went out to God for them, that they might stand true and faithful. After breakfast came a Confirmation. The school-church here, a very large one, was crammed. The leading chiefs sat in front, and the teachers all came in in procession with us. There were twelve candidates, and I gave an address--a shorter one than usual as there was so much to do. Service over, we all went out and sat under the trees near the beach. Mr. Plant and I addressed them first, and then we tried to get the people--especially the great men--to speak, but they were very shy. However, they brought forth a grievance, which was discussed. They complained that the labour vessels recruited quite little boys who had been forbidden by their parents to go, but who went notwithstanding; and I promised to pass on the complaint to the authorities. Surely it is a great thing that these men who, a few years ago, would have avenged such real wrongs with tomahawk and rifle, should thus temperately state their grievance, in the simple faith that the great Queen, whose men of war they have so often seen, would hear and redress them. After this followed [89/90] a discussion as to what should be the punishment for adultery (in old times visited by death), and it was decided to impose a heavy fine upon offenders. Then came what to them is a very vexed question of a homely kind--'What shall be done to a pig that trespasses?' The answer to this was: If anyone's pig destroys a garden, the owner of the garden shall say to the owner of the pig: 'Will you repair damages?' If he says 'Yes,' the pig lives; if he says 'No,' it dies. Finally I laid down some very clear laws for the guidance of the teachers, who have sometimes driven people away for quite trifling offences, or imposed fines on their own responsibility, which cannot be allowed. By this time the patience of the audience was exhausted, and we adjourned to the feast the Belaga people had got ready for us."

It was hoped these meetings would do much good in drawing the people together and creating a wholesome public opinion, and Mr. Plant, who had worked very hard, was much pleased with the success of this opening Parliament. He congratulated himself that sixteen chiefs were there--all except Dikea and Takua of the recognized chiefs of Florida. Of these sixteen, eight had been baptized, and all the rest, except Lipa of Olevuga, were either catechumens or hearers.