IT was about the same time that Alfred Lombu settled also amongst his own people in a distinct though not a distant part of Florida. He, too, had his matrimonial difficulties, but it must be admitted they were a good deal his own fault. He aspired ambitiously to a daughter of the great chief Takua, who did not refuse his suit, but insisted on having £50 from Alfred as the price to be paid for the honour of such an alliance. Wives are almost always sold in Melanesia, but this was an impossible price. Alfred had not got it, and withdrew his suit, whereupon Takua, feeling that he and his daughter had been made ridiculous, was very angry, and insisted on Alfred paying a heavy fine. After this it would not have done for Alfred to stay on as Takua's teacher, so he left Boli and went to Halavo, where he has stayed ever since. In 1883 he was doing such good work that he was ordained deacon amongst his own people. He had been greatly worried by some of the usual native quarrels and back-bitings, which are for ever cropping up in heathen villages, and these had made him very unhappy; but when the time came for his Ordination he believed himself to have conquered his resentment, and great hopes were fixed upon him. It was, therefore, a great grief to find that his self-conquest had been so imperfect that within a few weeks of his Ordination the old bad spirit had revived and Alfred had gone right away, leaving his flock to take care of itself as best it could for months.

His has been a chequered career. His example has not shone with the steady, undimmed brightness of his friend Charles Sapibuana, but if at times he has given way to temptation, he has deeply repented, and he has now been a priest doing valuable work for two years.

Of course all the neighbouring stations help or hinder one another more or less, but each is a little world in itself, and the teachers have each to fight their own battles with heathenism, and sin, and ignorance. No doubt the work of the two friends strengthened each other's hands, but they were both too busy to meet often.

One of the first-fruits of Sapibuana's home work was the conversion of his own brother Musua and his wife. Musua was baptized Philip, and from that time was Sapi's right hand, leading the village opinion and influencing it for good, for the short [78/79] time he was spared to Lango. He was very useful indeed, so that it was a great loss to the Church as well as a personal grief, when he died suddenly a short time after his baptism.

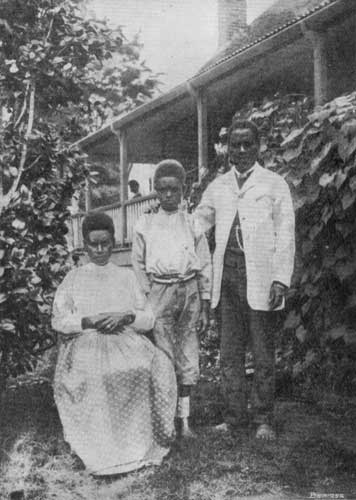

(From a Photograph by Mrs. O'Farrall.)

But through joy and sorrow the work progressed. In September, 1878, we read of surprise at the size Lango had grown to owing to people settling there for teaching, and "of a very bright day at Gaeta, beginning with the baptism in the early morning of fifteen adults and two children, all well grounded in the simple truths of Christianity. They are the first-fruits of Sapi's work, and it is specially cheering as being the result of a young man working amongst his own people. It has not been accomplished without opposition, even to threats, against all of which Sapi has stood [79/80] firm. 'It is all one. I trust in God,' he wrote. And after the baptisms came a wedding. The bridegroom is one of our teachers, and the bride, though she has never left the Floridas, was able to read her own part of the marriage service."

Next year, 1879, Mr. Penny writes: "Charles Sapibuana with a small staff of teachers under him, has been allowed to begin a most wonderful work. I have never witnessed anything like the stirring of hearts I have seen at Gaeta this year. It is wonderful when I remember that three years ago I was warned not to sleep on shore at Gaeta, and that two years ago Sapi's life was in great danger, threatened on all sides because he refused to attend a heathen sacrifice, and now he exercises a moral influence over a large number of people, who obey him and trust him as they would a chief. An earnest and deeply interested congregation of between forty and fifty attend daily at Matins and Evensong, and on Sundays the numbers are three or four times as large.

"A month passed rapidly at Gaeta. There were thirty-five candidates for baptism, to whom I devoted myself, schooling with them morning and evening. After morning school the people at Gaeta disperse to their work, for, as here they work all the year round, they do not go at it so violently as they do at Boli.

"When the baptisms drew near, Sapi and I were engaged often till ten o'clock at night, talking to parties of two or three, one set coming on after another until we used to get so sleepy we could see no more that night.

"On my fifth Sunday at Gaeta I baptized the first set--five married couples and an old woman and her grown-up son. It was a most interesting service, watched by a large and deeply interested congregation."

There was an interval before the next set of candidates was quite ready, and in the course of it Takua lost one of his wives--a kind-hearted, good woman, half-sister to Sapibuana, who was very fond of her. She had been ill, but some simple medicine did her so much good that she got out and about as usual till she overtired herself with a hard day's work, and never recovered.

The women came from all parts to wail when they heard of her death, but, after consulting Mr. Penny, Takua sent them away. Mr. Penny told him there was nothing wrong in it, but Christians did not do it; and the chief decided to follow the Christian custom on the occasion.

Of course no white missionary could give up his whole time to one place, and Mr. Penny had to go the rounds of his district, but he writes once more of the delight of getting back to the civilized Christian life at Lango after five weeks' absence, and of finding the new Christians happy and doing well, and the number of those wishing for baptism still on the increase.

Lango is two or three miles inland, and stands on high ground, so that it is cooler and much healthier than the spot where Kalekona lived down by the sea. Kalekona had been ill this year, and had gone away for change, to get out of reach of the [80/81] Tindalo, whom he believed to have bewitched him. He was back again, however, when Mr. Penny paid his second visit, and very glad to see him, but began at once to apologize for a small accident which had happened to Mr. Penny's boat during his absence. A locker had been left unfastened, and some children had scrambled up to play in it, and broken it slightly. It was a very little matter, soon set right, but Kalekona was very much annoyed at any harm happening to Mission property whilst under his protection, and ever after the boat "was tapu, with one hundred porpoise teeth." This means that no one must touch it without leave on pain of paying a fine of one hundred porpoise teeth. These are the money of the country, and each is worth about a penny; so the fine was a heavy enough one to act as a deterrent.

Kalekona had his good points, but in those days he was an undisciplined savage, which made him dangerous in proportion as he was powerful, and this in 1880 led to his allowing, if not actually abetting, the murder of a boat's crew from H.M.S. Sandfly. Lieut.-Commander Bower and several men died simply because Kalekona happened to be in a bad temper one day. Someone had stolen money, and Kalekona was in a rage, and felt that nothing but a head--it did not matter in the least whose head--could comfort him. So when five men from the Sandfly landed on a little island just opposite Kalekona's village to sketch and bathe, the chief allowed a party of his people to paddle across and surprise them.

Suspecting no danger, the sailors had landed, leaving their arms in the boat, and were all murdered except one, who managed to escape, and after much dangerous hiding in the bush, asked the protection of Tambukoru, the chief of Hongo, a few miles off down the coast. Happily for the fugitive, Tambukoru was a rival of Kalekona's, so did not give him up.

Of course it was necessary to punish Kalekona for his share in the business, as, though nobody was certain till later how far he had promoted the massacre, there was no doubt he could have prevented it had he exerted himself to do so.

The Southern Cross had left the islands for Christmas when the murder took place, but when she returned next year she found H.M.S. Cormorant lying at anchor in the Florida waters, on her way to punish the murderers, and as the Captain wished to have the help of the Mission in investigating the case, they passed on to Gaeta together.

The Bishop called Sapi in to help him, and together they questioned such natives as knew about the murder, to find out who was to blame. There was abundant evidence, unhappily, that Vuria, a young son of Kalekona's, had been amongst those who hunted down Lieutenant Bower when trying to escape, and there were even rumours that it might have been Vuria who fired the shot which killed him in the tree where he had taken refuge. But this was not proved, and the Captain of the Cormorant begged Bishop J. Selwyn to see Kalekona and tell him that if he would surrender the five men who were proved to have been concerned in the murder the [81/82] matter should be considered settled. These were really very lenient terms, but one of the party being his own son, it was a great deal to ask of the chief.

So Sapibuana accompanied the Bishop to Kalekona's village. On one side the chief advanced with an armed band, on the other were Sapibuana and his people, so the Bishop sat down on the sand between the two parties and sent for Kalekona, who came unarmed and with only one follower, and they held a long conference.

It was a hard thing to urge a man to give up his own son to be tried for murder, and possibly to be executed for it, and Kalekona could not at first consent, even though the Bishop promised to intercede for the lad's life. However he sent in one man, Holabesa, who was supposed to have been the ringleader, and said that "the rest had escaped."

Vuria himself behaved very well. He was quite ready to give himself up and trust the Captain's word that his life should be spared if he did so, but the poor father doubted, and hesitated still. At last the Bishop and Sapibuana persuaded him to go on board himself and talk it over with Captain Bruce, and he went.

It was very early in the morning of Ascension Day. Lieut. Bower's skull, which had been kept in the boat-house as a trophy, was brought in, and with this and all the property which had been looted from the Sandfly's boat they started to go on board the man of war.

It was not surprising that the people were very angry with Sapibuana, and told him that if their chief did not return safely they would at once make an end of him and his school. But Kalekona himself, when once he had made up his mind, never flinched. He went on board and handed over to Captain Bruce in order of value, first the goods, next the skull, and last of all his son, Vuria. Then all returned on shore, Kalekona remarking that "an English Captain could not lie"; after which the Christians held the Feast of the Ascension together, with hearts full to overflowing of thankfulness for the way the terrible episode seemed to have been turned to good.

Soon afterwards the real murderer was identified, caught, and executed on the very tree in which he had shot the naval officer. A large number of natives were present, and seemed much impressed by the whole matter--the strong far-reaching arm of English justice, the pains taken to punish no one except the guilty, no indiscriminate revenge taken. [The participators in the murder to the number of six were caught and executed in their respective villages. Vuria, as we have said, was pardoned, and one (Puko) escaped.]

The way Sapibuana had behaved throughout was so excellent that the Bishop felt the time had come to ordain him Deacon. In the course of that May they gathered at Lango for this great happiness, Mr. Penny, who had worked with him for so long, presenting him for ordination, and the service being held amongst his own people of Gaeta. At the early Celebration there were seventeen Communicants, as [82/83] many teachers and their wives had assembled, and at the Ordination Service itself, which was held in the evening, there was a very large congregation.

It is given to very few to receive the Laying on of Hands so absolutely amongst their spiritual children as it was to Charles Sapibuana. It was his influence which had brought most of them to live at Lango at all. He had led them to the font, taught them, and influenced them for good, and they were "his crown of joy in the Lord." No wonder it is spoken of as a deeply moving service.

And though it was a climax it was also a beginning. For three more years he lived and worked amongst his people, his work growing deeper and holier, and his influence extending as he grew in the Spirit. It was a very remarkable early ripening. He had certainly very much of what Clement Marau has called "spiritual power"--a Christian version of the native idea of mana.

But the care of the churches is very hard work physically, and such work as Sapibuana's was requires a man's whole energy to be thrown into it, and is most exhausting; so that when, towards the end of 1885, the Bishop felt he ought to be ordained Priest, he did not have the Ordination at Gaeta, but took him with wife and children to Norfolk Island, in the hope that the few months of reading for the priesthood would give him the rest he so much needed. But his was to be a longer rest than that. It was an unhealthy season at Norfolk Island, and soon after the return of the vessel influenza appeared and spread rapidly. Sapibuana, in an already enfeebled condition, could not resist the disease; lung complications set in, and he died after a few days' illness, to the intense disappointment, as well as grief, of the Mission Staff. He was not one for whom to sorrow hopelessly, and he had done a good day's work, though it might be only a short one. But he was their most promising pupil--the one of the native clergy who seemed most likely to be ordained of God to do great things in the future, and it was very hard to acquiesce cheerfully in his sudden removal, the blank left was so great.

If they felt this at Norfolk Island they could not but feel it yet more when next year the Southern Cross called at Gaeta to leave the widowed Georgina and her children. Mr. Penny had been called away to England by duties, and Mr. Plant, a stranger to the islands, had to go with her on that sorrowful homecoming. He writes thus of the long uphill walk to Lango:--

"The whole journey there was very touching, and gives strong evidence of the good Charles Sapibuana had done amongst his people. For instance, in one place we had to cross a rough stream, on the other side of which an old woman and a girl were getting water. A man who had attached himself to our party called out loudly, 'Sapibuana is dead!' at which the old woman at once gave an exclamation and began to cry. But the girl, a strong, thick-set, stupid-looking creature, sat where she was, staring stolidly at us until Georgina, having crossed the stream, went and stood [83/84] before her with hands outstretched. Then the poor girl, without rising, seized Georgina's hands, and burying her face in them, burst into a passion of tears.

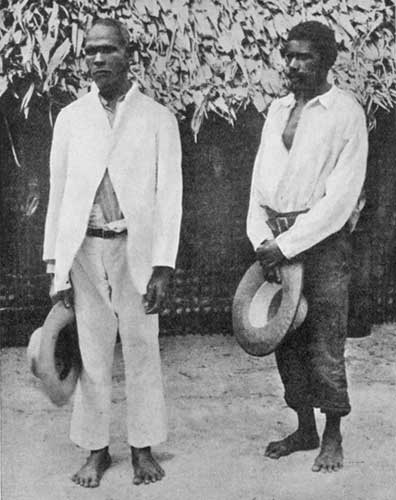

(From a Photograph by Bishop Montgomery.)

"When we got into the village, and the sad news became known, the men huddled together in silent grief, and the women wailed. Men would meet us on the road and shake hands, but could not trust themselves to speak. That same evening, after service, as the Bishop and I were walking through the village together, we came upon a young under-teacher, a little, rough, dirty fellow with a head of hair like a London street arab, who, having just heard the news, was leaning against the comer of a house with his face buried in his hands and sobbing as if his heart would break."

But with all the sorrow there was no confusion. Things had been left in the hands of Mostyn Vaguru, as head teacher, for the months during which Sapibuana [84/85] was to be absent; a provisional arrangement which had worked well and would go on. The Christian foundation of Gaeta life was too well laid for its permanence to depend on the life or death of any one man, and Lango remained an orderly highminded Christian village, though its first brilliant "joy in believing" could not but fade.

There was good news from the neighbourhood too, for Mostyn had not only attended to Lango, he could show with pride a school and schoolhouse at Hongo, a little further down the coast, where he had a class of sixty prepared for baptism, at the head of which was the chief Tambukoro, that former rival of Kalekona's, who had sheltered the one survivor from the Sandfly's boat.

Tambukoro, when the day came for his baptism, chose for himself the royal name of David, which he liked as appropriate, for by the better class of chiefs their duties and responsibilities, as well as their rights and privileges, are strongly recognized.

Kalekona died a Christian. By the time we are speaking of he had already put away his Tindalos, as many in that neighbourhood were doing. Many strange-shaped stones, supposed to have mysterious powers connected with dome Tindalo, were surrendered at that time. They had been regarded with superstitious reverence, though not exactly worshipped, and it was considered better to get rid of them altogether by rowing some way out to sea and dropping them into really deep water. A few were kept; for instance, Kalekona's own ancestral "Devil Stone" he presented to Mr. Penny as a curiosity. It was about the shape and size of a lemon, rudely fashioned into the likeness of a human head, and was considered very powerful and very sacred indeed.

When these Tindalos were got rid of, and the intricate tambu system greatly relaxed, many people spoke of the sense of freedom. One was heard to say that it was as if now it were possible to walk along lightly and easily, whereas in the days of the tambu and Tindalos it seemed as if they were always bending under a heavy weight. They had experienced already "the glorious liberty of the children of God."

And Vuria had not gone back after the lesson he had had. He was very friendly with the school people, and during this first visit of Mr. Plant's he took him under his guidance and interpreted for him, besides setting the example of helping him in his own coast village.