BUGOTU is not even now an easy place to live and work in, though it is very different from what it used to be in Bera's days, as the head chief, Soga, who had succeeded him, was a Christian, and many of the petty chiefs were under his influence for good, so that there was a great deal of encouraging work to be done. But there were many villages at considerable distances apart, and the hills that divided one village from another were very steep.

This was the style of work. We read that on September 4th they anchored at a place called Pirihadi, and climbed over a hill 700 feet high to Pahua. That evening the Bishop addressed the baptismal candidates, of whom he baptized thirty next morning. After breakfast they set off and returned over the hill another way to the Southern Cross, which was ready to start, and at once dropped a little way down the coast to Vulavu, where she anchored once more. Then came another climb of 800 feet to Rate, where came another Baptism and address, this time with over forty candidates. Back to the vessel they hurried for tea and an hour's run down the coast, so as to get in another Baptism of twenty-seven, a teachers' meeting, and a Communicants' class before the day ended. Next day began with a Celebration for about twenty Communicants; on, after breakfast, to Vahoria for thirty-five Baptisms, more boating, and the day closed with forty-eight Baptisms and the usual address. To baptize 180 in the course of two days would be tiring, even if they were all infants, and the mental strain of so much joy must have been overwhelming, besides the physical exertion combined with it all.

Head-hunters from New Georgia were just then infesting the coasts of and near Bugotu, and Dr. Welchman asked the Bishop what he, as a layman, must do if they made an attack? Ought he to take a rifle?

"No!" was the decided answer, "you must not fight; you are a quasi-ecclesiastic." "But," he added, with a ring in his voice, "you can go round with a stick and encourage the people to defend themselves." He believed in self-defence, though not in fighting for fighting's sake, and liked nothing better than to hear of people making a stand against these cowardly murderers. Missionaries new to island life were at first inclined to blame as lazy or too proud for manual labour men who left all the heavy work to the women. They would meet a woman, for instance, staggering [50/51] along a steep bush pathway, bending under a load of heavy bamboos full of water, whilst behind her came her lord and master, lightly clad in shield, spear, and tomahawk. But experienced men saw the sense of it. "It looks bad," said the Bishop, "but it is really the best thing. The women can carry burdens, but they cannot fight, so the men go to protect them, with their hands free of all but their weapons."

So on through Melanesia, up and down, climbing, sailing, wading, regardless of what was good for the over-strained body, the Bishop went on, until, when he went on shore at Mota, he broke utterly down, and though after a time the vessel took him back to Norfolk Island as quickly as possible, he was in bed there for months with abscesses caused by malarial poisoning. Even then he would not give up work entirely. He confirmed from his bed some boys and girls returning to their homes, as they would have no other opportunity for years. The doctors absolutely vetoed all work at last, and when it was possible to move him he went home to England to consult surgeons there. It was a great blow to himself, as well as to his friends, that the English doctors absolutely forbade his return to the Pacific. Indeed, they told him he must regard the island work not as merely unwise, but as impossible in the future.

He was on crutches for the remainder of his life, and could not have climbed over the vessel's side, or swum ashore, or walked through the steep bush paths. He himself had begun to feel that "perhaps a change might be better for the work," and though no other man thought so, God doubtless did, since He removed him, and once more left Melanesia for some years without a Bishop.

The contrast is great between the two interregnums. The progress had been most thankworthy in the twenty years since Bishop Patteson's death, when Mota held the only really Christian village, and George Sarawia was the only native deacon, and there were no native priests at all. When Bishop John Selwyn left Melanesia, never to return, there were native priests at Ara and at Mota, and some six native deacons still living, and the memory of five others, three of whom had died, leaving bright examples which still bore excellent fruit--Edwin Sakelrau, Edward Wogale, and Charles Sapibuana--all men whom it had been hard to part with in the vigour of their usefulness; but the very fact that the Mission had been able to rear and educate three of such different types of sterling excellence was a great sign of God's blessing on the work. Though laid aside from work, Wadrokal was still alive, but he died very soon after in his own island. There was one memory of great promise, most terribly blighted, one deacon who had done most excellent work for some years, and then fallen away, never to rise above the waves again. But such a case was a very rare exception, thank God. Though there had been other falls amongst teachers, most had risen again through penitence, and had, after excommunication for a period, drawn near once more to serve God and man in the Church.

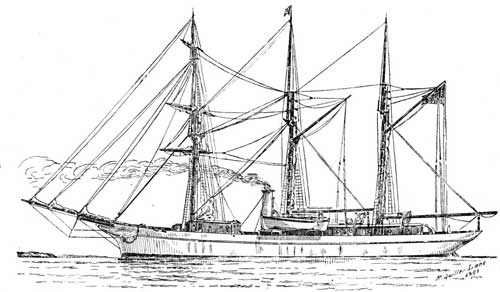

Three-masted Schooner. Foremast, square rigged; main and mizzen, fore-and-aft rig. 240 tons. Auxiliary steam. 1892 to 1902. Built in England. Cost about £9,000; contributed by Bishop J. R. Selwyn and other friends.

[52] We must not, grievous as they are--think of these fallings away of the Melanesians as if they were those of teachers and preachers in civilized lands. In many cases what we call impurity, and which had to he dealt with by the much-dreaded punishment of being shut out from the Christian fellowship for a time, was to them only a return to the old unseemly marriage customs, in which the heathen around them still saw nothing to blame. Christian marriage is indissoluble, and all baptized Melanesians know they must treat it so and acknowledge the breach of it as sin. But they have had to learn this, and learn it (after they grew up in many cases) as a new idea. Until we have seen heathenism, we are apt to think of it chiefly as negatively evil, but this is hardly true. Heathen society is so dark in all its ways that those who rise above it in moral tone, as many do, are like men swimming strongly in a stormy sea, which is drowning those around them; or they are like men bearing torches in an obstructed wood: some do stumble and fall, [52/53] and now and then a torch is really extinguished, but the promise has been most abundantly fulfilled that the man who feareth the Lord, "though he fall he shall not be cast away, for the Lord upholdeth him with His hand."

Another great mark of progress in these twenty years was the change of opinion with regard to the power of ghosts and other spirits. The heathen had been in perpetual bondage to the fear of ghosts and spirits, and the things and places they believed it to be unsafe and unlucky to do or to go to covered life with a network of danger. But the persistent manner in which the missionaries shewed in practical ways their disregard of such fears, and yet suffered no harm by doing so, struck the heathen very forcibly. They saw that Christians could walk in places where others were afraid to venture, and eat food that was tapu, and no harm happened. Of course, all had to be careful not to hurt people's feelings, and often, therefore, abstained from many things there was no danger in; but the fact that their want of dread of Tindalos was not followed by misfortune gradually undermined that fear itself in native hearts; and in the Floridas there has been a wonderful clearance made of objects of superstition, the stones being brought out and thrown into the sea, which once were venerated as full of "Mana," and the sacred enclosures destroyed that people hardly dared approach formerly, much less treat with disrespect. Of course, there is plenty of superstition still, but it was nevertheless a great day in the annals of the Church of Melanesia when Kalekona and his neighbours brought out their "devil stones" for the missionaries to destroy.

When forced to give up the Bishopric of Melanesia, Bishop John Selwyn did not drop his interest in it or care for every detail of its history. Not only was he the home centre which all foreign dioceses need, but he subscribed most liberally to provide a new and larger Southern Cross, which was built in England, and reached Norfolk Island ready for use in 1892.

There were great rejoicings over this generous gift, which would, it was hoped, in all ways be a great advance on its predecessor. But, unhappily, it had to be built when Bishop J. Selwyn was far too ill to personally superintend its construction, and the friend to whom he trusted the work had not his intimate knowledge of what a vessel for the purpose ought to be; so that the vessel proved a considerable disappointment, and at the end of ten years has to be sold and superseded by another--the fifth of the name.

Again, it was years before the right person could be found to meet the very peculiar requirements of the Diocese, and this time the work was much less easy to manage. We have seen that in one corner of one island alone there were nearly two hundred Baptisms in two days, and the advance was in proportion in other places; and that meant that in a few years these people would, many of them, be ready for Confirmation.

[54] In 1892, therefore, the Bishop of Tasmania paid a visit to Norfolk Island, and after much that was necessary had been done there he proceeded on the island voyage, and what he saw and heard he has told us in a delightfully vivid little book, "The Light of Melanesia," from which we have quoted freely.

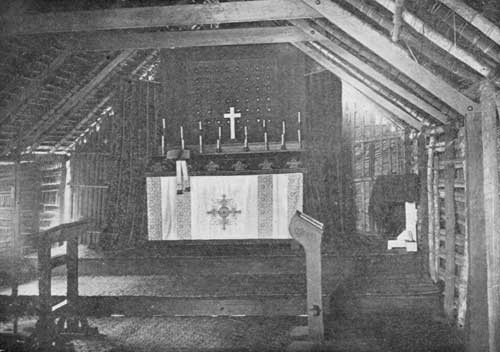

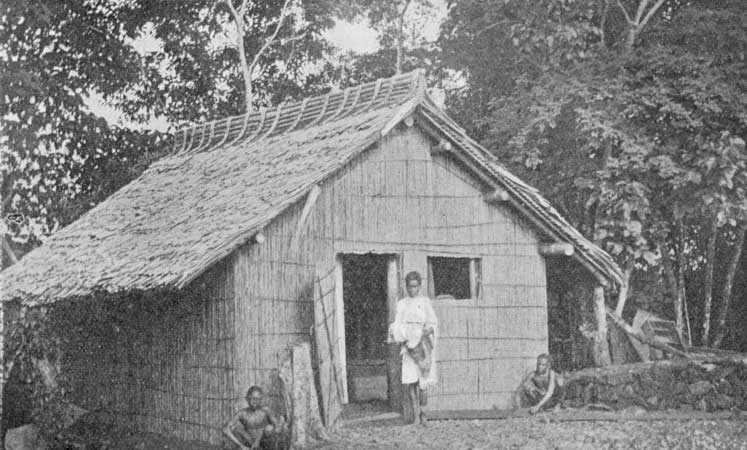

(From a Photograph by Rev. W. C. O'Ferrall.)

As time went on the white missionaries found that it was not impossible to spend the summer in the Islands. They felt that if traders could do it for profit, missionaries must surely do it for the love of God and their neighbour, and accordingly some of the staff now always spend Christmas in the Islands, whilst others return to Norfolk Island. It is less dangerous to health now than it was when the Islands were less known, because the missionaries know in what the danger lies, and are able to take proper precautions. Also there are better houses, and they try to live a little less roughly. To sleep and eat in gamals for months together is so dirty and uncomfortable as to be a waste of power, although it must be done to begin with everywhere as the best means of getting at people, and does not matter for a few nights and days between visits of the Southern Cross and sojourns in comparatively comfortable school-huts. It is true there are mosquitos, and centipedes ten inches long, and with [54/55] a most painful bite, which live in the thatch and walls of these huts, so they are not altogether ideally healthy or comfortable But, still, it has been found possible to keep going, and it is becoming most important that the supervision by the white clergy should not be suspended each year during the summer months as used to be the case.

When it was decided to have a central school in the Floridas, at Siota, on Boli Harbour, an excellent house, with many European comforts, was built, and an attempt was made, in 1896, by a married missionary to take his wife there. But, grievous to say, she died in a very few months, and no other lady missionary has so far lived for any length of time in the Islands. There is, however, a hope that another attempt may be made shortly in one of the groups.

In speaking of St. Luke's, Siota, we have anticipated a little, for it was not founded till after Bishop Cecil Wilson had been consecrated in 1894.

(From a Photograph by Rev. W. C. O'Ferrall.)

With the annually increasing demand for well-trained teachers, it was now felt that St. Barnabas' College must more nearly approach its ideal of being not so much a school for the conversion of heathen as a college for the training of candidates for Holy Orders and first grade teachers. St. Luke's, Siota, was founded with the idea of providing a training-school for junior teachers in the Solomon Islands; those of its scholars who shewed most promise being drafted to the Norfolk Island College for more advanced teaching. A corresponding institution is about to be started at [55/56] Vanua Lava, in the Banks Islands, which will serve the same purpose for the southern part of the Diocese.

Such pains had been taken to make the house at Siota a good one, and to attend to everything that could possibly be necessary, that it was a great blow when, after a few years' trial, the fact had to be admitted that it was not healthy. The first year or two they hoped the illness was either epidemic or the fault of that particular season; but it went on and on, and at last it had to be faced that the scholars were not well there; and the school has been dispersed for a time whilst a swamp on the sea shore, close to the college, is being drained. This work is being carried on energetically, and a great part of the swamp has already been got rid of.

A few years ago the Solomon Islands was taken under the political protection of Great Britain, and there is now established and living chiefly on a small island of the Florida group, an English Commissioner or Resident, Mr. Woodford, to keep order in those seas. The force of police at his disposal is small--far too small to put down the head-hunters effectually if there were determined attempts at violence. At the same time, it has an excellent effect on the ill-disposed to know that England is watching their coasts, and will send a man-of-war to support the Commissioner if there are any disturbances.

This Commissioner, when first he came, did not know whether he should find the missionaries a help or a hindrance. Of course, he had heard shallow talk about them, as we all do. However, after some years' experience he has come to feel so strongly the value of Christianity as a civilizer and keeper of the peace that he has asked their help, intimating that the Mission must forthwith place missionaries in certain districts, and that if the Church cannot he must ask others to do so. This demand has been to some extent met, for it is most important the native ideas should not be confused by having different bodies of Christians on the same island, but the Mission sorely needed more men to occupy the posts which are vacant.

In 1898, just seven years after his resignation of the Diocese, Bishop John Selwyn died in Europe. To the end of his life he was a missionary at heart, and he urged on and encouraged others when they went to take up posts "at the front" of the foreign mission field. Eventually it is hoped a really noble church may be built at Siota as a memorial of him; but for the reasons mentioned above, it is not yet begun.