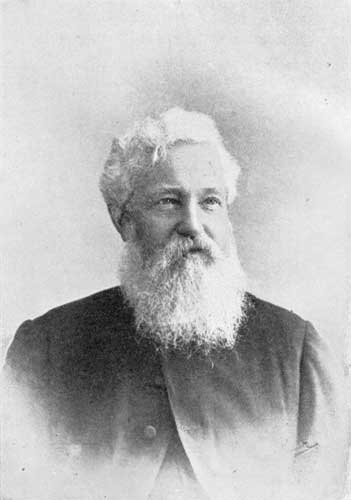

THE Episcopate of Bishop John Selwyn lasted fourteen years, from 1877 to 1891. It was a time of much real progress, each island visited progressing a little year by year, and some doing so to a very remarkable extent. But the progress was so gradual and the number of different islands is so confusing that it is not easy to give a detailed story of year after year.

It will be better to give a few general remarks, and then speak of the different groups in turn. As we have said, we do not attempt to chronicle the history of the white missionaries, though we know what valuable lives have been spent in the service. Their works follow them, and their spiritual children rise up and call them blessed. But there is one--only very lately called away from the work that can ill spare him--of whom we must speak a few words. Mr. (later Archdeacon) Palmer bridged over the gulf between the days in New Zealand and the present time. What he and his were to the mission during nearly forty years no words of ours can tell. In the Islands he was specially associated with the Banks group, but he had been connected with the Mission so much longer than anybody else that nobody can quite take his place at St. Barnabas'. He and the first Mrs. Palmer established the first scholars there, and there was much that he knew, and which has now dropped into a memory only.

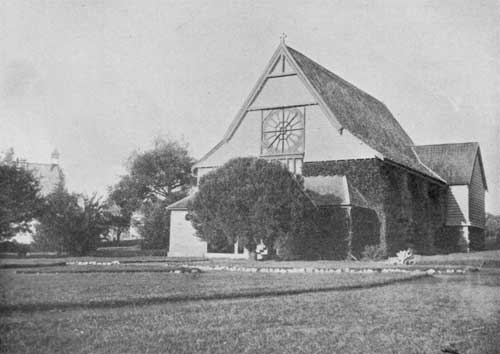

We have spoken of the new Southern Cross as being part of the memorial to Bishop Patteson. The rest of the money was spent on the beautiful stone Church which now stands in the midst of the wooden buildings of St. Barnabas' College. It is very fine in itself, and full of meaning. Every detail has been carefully thought out--the flooring marble from the Bishop's native Devonshire; the ends of the seats inlaid with mother of pearl from the islands; the painted windows recalling the many who had given themselves by life and death to the service of the Mission, as well as telling Bible stories by their subjects.

It has a beautiful organ--the gift of Bishop Patteson's cousin and life-long helper, Miss Charlotte Yonge, of Otterbourne. Melanesians are very musical, and they greatly enjoy and appreciate their organ, which several of the native boys learnt to play well. John Pantutun, for instance, the son of the Rev. Robert Pantutun, of Mota, was organist for some time, managing the pedals admirably with [42/43] his bare black feet. Instrumental music is a pleasure impossible to them in their own homes. There have been attempts to bring harmoniums to the islands, but they never last long. To begin with, it is hard to land them dry from the boats tossing up and down against the steep coral strands in a heavy surf. Then there is the dragging them up the paths on the hill-sides, which is not good for harmoniums. [43/44] However, all this could be got over if it were not for the climate. No harmonium has ever yet been invented which will not come unglued in that moist heat, after which mice make their nests in the bellows, and white ants eat the case! It is very disappointing, but so it is, and the choirs of the various churches have to content themselves with vocal music in consequence.

Built in memory of Bishop Patteson. Consecrated 1880.

(From a Photograph by Rev. L. P. Robin.)

Bishop John Selwyn's seamanship and love of managing a boat appealed to the Melanesians, who are almost equally at home in or out of the water (in spite of the sharks with which their seas swarm). But the perils on the waters were constant and great, and even when nothing worse came of a dangerous landing than a good wetting with the surf, it was really a serious thing for a man subject to rheumatism and ague to have to spend the rest of the day, and probably the night also, wet through. After a rough landing there constantly ensued a day spent in talking and being talked to, often through an interpreter, and then followed the night in the draughty gamal, crowded with the "great unwashed" of Melanesia, who lay on [44/45] the ground round the central fire. There were no windows, but generally doors--holes at each end, not reaching to the ground, as pigs (though they do more than pay the rent in Melanesia) are not desired indoors in houses or churches.

The Bishop was proverbial amongst his fellow-workers for his thought for others, and once amused them by saying, "How selfish sleeping in a gamal makes one! One always looks out for the cleanest place to lie down on"--a remark which suggests volumes about what these club-houses must be at best.

When the bad effects of the climate and hard life began to show themselves it would be difficult to say; but we read of frequent attacks of fever or ague long before he broke down confessedly.

It was in the middle of his time in Norfolk Island that the patriarch of the Pitcairners, Mr. Nobbs, died in extreme old age; and his passing away brought the old era to an end. The Norfolk Island settlement of Pitcairners is now so far connected with Melanesia that it is legally, not merely by courtesy, in the Diocese; but the town and the College remain quite distinct, as they have always been. The S.P.G. gives part of the salary of the Settlement chaplain, but it has not helped the Melanesian Mission at all for many years now.

It is a difficult parish to suit with a pastor, and in vacancies and emergencies the St. Barnabas' clergy help in the township church. But the ideas of the Norfolkers are not of the strenuous kind instilled at St. Barnabas', and, moreover, they often have illness amongst them, which has to be kept out of the College, so that there is not very much intercourse between Norfolk Islanders and Melanesians.

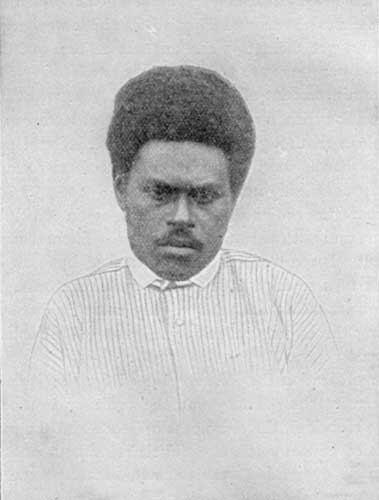

By the end of 1889 it was very evident to those around him that the Bishop's health was failing, and he found the island work, deeply as he loved it, tell very much upon him. He had paid a visit to the Solomon Islands, and found much to rejoice over in the good work that was being done by Marau--long ago baptized Clement--who had been working for years as a teacher there. So good had been his work that at the end of this year's voyage he was returning to Norfolk Island, there to read for and receive Deacon's orders, when Bishop Selwyn was suddenly disabled by illness. He was quite laid aside and unable to attend to his ordination candidate or to his other work, and as soon as he was fit for it had to go away for complete rest and change. In April, 1890, he was back again, much better, and glad to take up his work again. It is curious to contrast the tone of this last series of letters with those written fifteen years before. There is not less zeal, but there is a sort of mature patience, not merely with his own infirmities, but with the many little worrying ways of his island children. He is able to make fun now of many little hindrances which would have been annoyances when he was young to the work.

There is not more of special interest in the details of that year than of other years, but a few extracts from the notes about them will give an idea of how he lived amongst his workfellows and pupils. For two years running the College had been [45/47] visited at the same time of year by a sort of epidemic of brain fever, and when the season came round for the third time, the anxiety as to whether it would bring the illness was extreme. At first it seemed as if the enemy were upon them, for one day a boy came in with such a dreadful headache that he was for two days and a night in a comatose state. As the second night came round, the Bishop, much alarmed, was making arrangements for sitting up, when suddenly the boy roused up, his headache gone, and rather indignant at being fussed over. "Has the bell rung?" he enquired. "Then why don't you all go to bed?" a suggestion the Bishop followed with much relief. The boy got well, and the malady did not recur that year.

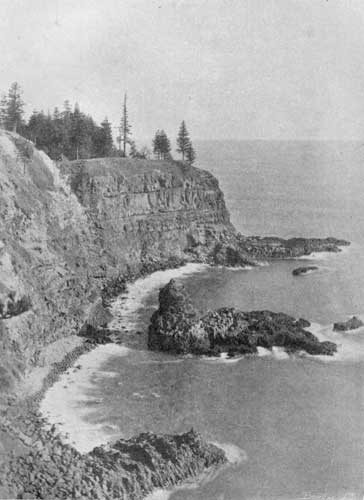

This is a fair specimen of the Norfolk Island Coast. High and precipitous cliffs capped by great Norfolk pines form the ramparts of the Island. Here and there, like sentinels, stand detached masses of rock, which have been named according to their supposed resemblance to animals or things--such as "the Crown," "the Seal," "the Castle," and "the Sail" Rocks.

[47] Clement's ordination was coming very near, and the reading with him for it was delightful. Once the Bishop chronicles how, apropos of a talk about prayer, Clement said to him: "Bishop, do you know what I pray for?" (He named two villages, one at each end of the heathen part of Ulawa.) "I pray for them, as I used to pray for two men in my village, and they are both Christians now." Another time he [47/48] gives an amusing picture of the two first classes over their geography and multiplication. "They are dear, good-humoured fellows, and enjoy my progressive system of punishments greatly. When a fellow does not know his tables he rises first to his feet, then mounts on the form, and lastly on to the table. Their reasoning powers are limited, and it seems to tax one's brains to the utmost to make them understand what we think a perfectly simple inference. Reading with an intelligent Melanesian like Clement is very restful work, after the incessant vigilance it takes to observe whether you have made yourself clear to an ordinary class. But I have pleasant times with those I am mostly teaching; they are docile and anxious to learn; and we have great fun over our sums and English. I think we hardly do enough paper work. I must try and get them to write answers more; but the slow ones of the class handicap one--a pen seems to paralyze their intellect."

There was a certain amount of intercourse that year with the Norfolk Islanders at the settlement, and the Bishop gave them a course of lectures on the cities of Italy, which gave much pleasure, though it was not easy to interest people who had seen or even conceived of hardly anything beyond their island rock, four hundred miles from anything much more enlightened than itself.

"Just back from the ordination," he writes again on July 5th. "Dear old Clement was so calm, and yet evidently much awed. There was a David-like episode which was interesting. I was troubled about it at first, but now I think it was good. It happens to be his turn to drive in the cows, and this morning, instead of sending the others of his set, he went himself, and only came in just in time to get ready. 'As he was following the ewes great with young ones, He took him.' God grant it may be of good omen."

Soon after the ordination the Bishop started for the islands--his last voyage, though no one knew it then. There was the ordinary routine of difficulties--the quarrels in the New Hebrides, the sleepiness of Mota, and the inconveniences caused by the secret societies in many islands. Their rules kept people from church and from school, and made everything very difficult, because some foolish (though not wicked) rule might prevent the whole population from going to this place, or eating at that, or washing at all for days at a time. In the Solomon Islands there are not these clubs, and the energetic natives from those parts were inclined to put them down as wrong in themselves. But there are plenty of real sins to fight without magnifying follies into sins, and the missionaries feel they must deal very cautiously with these associations.

From Boli harbour in the Floridas he writes: "I had a little experience this morning which was helpful. At 6 a.m. I went to Vuturua to land a couple of men, and found all the people assembled waiting for prayers, so in I went and had prayers with them. I had expected a rough bit of boating, and not to stop more than a few minutes, so I am afraid my costume was not very episcopal; but I do not think [48/49] they found anything incongruous in a Bishop in a white coat and no shoes. There were seventy people in church. I fancy that if a Bishop turned up 'promiscuous like' on a dark, rainy morning, he would hardly find so many in an English village."

In this voyage he went to Bugotu, and Dr. Welchman, then a layman and somewhat new to the work, watched with a mixture of admiration and anxiety what the Bishop called a day's work. But this we must leave till the next chapter.