ALL through that five years' interval the Santa Cruz group had been practically closed to mission influences. It had been felt by authority that (from a political point of view) it would be impossible for the British Government to take no notice of the murder of two of its subjects, and a man-of-war, therefore, went to the group to make enquiries. Unfortunately, they were not received peaceably, and the Captain felt it necessary to shell and burn a village, though he was careful to kill nobody. He felt if the opposition to their landing was passed over, the natives would think they had frightened away a man-of-war, which would be a dangerous precedent. It was punishment, not revenge. Still, the missionaries were very sorry it was considered necessary, as they felt the natives would not understand, and that it widened the gulf they were anxious to bridge over. But it may be that the needful lessons sank all the deeper into the Cruzian hearts from this entire separation from mission teaching and friendship during these five years. At least, they had time to think over what they had done, and to be very much afraid of the consequences.

It was given to Mr. Still to see the first opening that gave a chance of serving the Santa Cruz Islands once more. He had thrown himself at once into the work, and was very busy in St. Cristoval (Bauro), making his headquarters for some weeks at Wango, the village of the well-known chief, Taki, in June, 1876, when he found himself not merely in the midst of cannibals, which was common enough in Bauro, but actually face to face with a cannibal feast.

They did not ask him to partake, but it was a sickening experience, and on such occasions it is always a little difficult to know what to do. If one followed one's natural impulse to upset the oven, one would probably be its next occupant oneself, without having done any good. The natives had not in this district, though in most places they have, the power of understanding our horror and disgust at the idea of eating human flesh, and it is the harder to make them see the harm in it, because it is not necessarily murder, and so explicitly forbidden by God, although, of course, it leads to many murders.

In spite of all these things, he was pleased to find some progress, especially in the little island of Ulawa, where, in Mr. Atkin's time, it was considered hardly safe to land. This year Mr. Still stayed in a hut there, hospitably welcomed and [36/37] entertained by two men who had been to Norfolk Island, and as they talked of building him a house there by next year, he hoped then to make a real star there.

Whilst at Ulawa he heard a report that there were two Santa Cruz islanders at a place some miles down the coast. The story was that these two men were the only survivors of a party whose canoe had been blown away from their own islands and had drifted to Ulawa. Some had been killed, and their canoe had been broken up, but these two, whose names were Lapio and Puia, were saved. They married women on the other side of the island under the protection of a chief called Hohou.

The village was too far off for Mr. Still to walk to it, but he sent messages to ask the men to come to him, hoping he might be able to restore them to their own island, and thus once more open the door for friendly relations with their people. But the men dared not come: they thought he must want to kill them in revenge for the Bishop's murde ; so Mr. Still had to leave it for the present, though he greatly feared that before he could get there they would be killed and eaten.

About two months later, when the Southern Cross came down, Mr. Still found the opportunity of reaching the village, and with three trustworthy Christian boys walked over to pay a visit to the chief Hohou, and if possible to bring back the Santa Cruz men with him. There was a good deal of excitement in the village on the arrival of the visitors, as a white man had never been seen in those parts before. Men ran in from all sides fully armed, but after a few words of greeting the weapons were laid on one side and all were friendly. At first the Santa Cruz men were too suspicious to come near. They were afraid that the white man had come to avenge the death of the Bishop, and stood at a distance, nervously handling bows and arrows. A message was sent to them with a small present, and after a while their fears were overcome, and they shyly approached. Mr. Still heard from them for the first time the story of the Bishop's death, and of the visit of the Labour Ship to Nukapu a few ~ days before, when, after killing four natives and wounding four others, they had stolen the five who had ventured on board. It was interesting to find that one of these two men, Lapio, had actually been in the canoe overhauled by the Bishop in the ship's boat the day before his death, and he described graphically how, when the canoe fled from the boat, the Bishop had stood up and held a present to show his peaceful intentions. They also said that they had then warned the Bishop not to go to Nukapu, and this, Captain Borgard of the Southern Cross, confirmed. Unfortunately, they could not be persuaded to trust themselves to the care of a white man, and refused to leave their new home. This visit and interview, however, stimulated the longing of the missionaries to once more gain a footing in the Santa Cruz islands.

The opening for friendship seemed so important that next year, Bishop John Selwyn (who had just been consecrated) went himself to Wango and Ulawa. He discovered that two castaways from Santa Cruz had been heard of at a place called Port Adam, on the coast of Mala, some ten miles from Saa, whence came [37/38] Joe Watè and his brother, the chief, whose name also was Watè. Chief Watè was a rough, noisy sort of man, not much use to the missionaries, though not actually unfriendly, and the Bishop hoped more from the second chief, Dorawewe, whom he interested in his enterprise. It was a dangerous one, for, bad as Mala is in general, Port Adam had rather a specially bad name on its coast, and when the Bishop rowed down there he did not take a large crew, lest a number of strangers arriving should excite suspicion. The people, however, did not prove unfriendly, and at last he found the place where the men were, and Oikata, the cannibal chief who owned them as slaves, said he "would let them go if Besopè offered enough." Besopè did not like buying men, but if looked at as redeeming slaves, considered it justifiable.

Oikata proved slippery and very hard to deal with. A fortnight passed, and still the men were not handed over, though they were certainly very anxious to get away. Indeed, as Oikata, after much shuffling and haggling over prices, only finally gave up Tuponu (who, being very thin and afflicted with sores, he did not think it likely he should require), they could not possibly be less safe on board the vessel than they were at Port Adam.

It was hard to go away and leave the other man to his fate, but it would never have done to let the chief think he could bully the missionaries into giving him twice as much as he had any right to ask, and as it was they were in the utmost danger as they left Port Adam. Captain Bongard, the experienced skipper of the Southern Cross, noticed symptoms of an attempt to cut them off, and bows and arrows were being got ready for fight; but the vessel being steered out of reach at once, the men of Port Adam were saved from themselves.

Tuponu did not come from Nukapu, but from Nufiloli, another of the Reef Islands. It was found impossible to make his own home, so as to land him there, tides and winds being contrary, but happily he did not mind this, and his short stay on board the Southern Cross had made a beginning of friendship with his people and had also enabled the Bishop and Mr. Comins to pick up enough words of the language to speak to the Cruzians to whom they handed him over. It was, almost to the day, six years since Bishop Patteson's death when they did this.

According to Tuponu, though the large island of Santa Cruz is populous, the small Reef Islands were very much the reverse now. The labour vessels had carried off some people, and the epidemic we have mentioned spread fearfully in the dirty, crowded houses, where the people no doubt died all the faster because they were panic-stricken and thought an avenging spirit had caused the sickness as a punishment for the murder. These small islands, with an average population of some thirty each, could only be regarded as stepping-stones to the larger one; but it was a great thing to be able to land at all in that group, to go as friends into the house of the chief, and themselves tell the story of the castaways and their [38/39] efforts to rescue them. The people were so friendly that man after man jumped into the stern sheets as the boat pulled off and rubbed noses with the Bishop. As they have awful-looking mouths, full of black teeth disfigured and distorted by chewing betel and other such disgusting habits, this probably was more agreeable to the mind than to the senses.

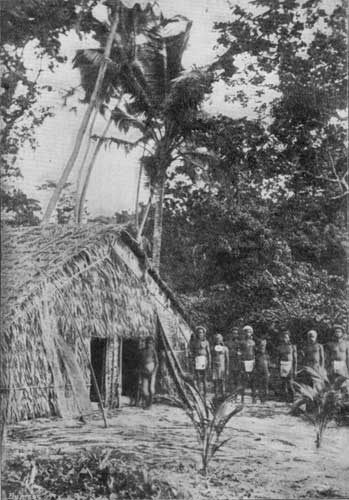

(From a Photograph by Rev. W. C. O'Farrall.)

In fact, the attraction of the Santa Cruz islanders in comparison with many other natives is a thing we who have not seen them must take on trust. There is evidently something that makes people yearn over them with a very special yearning, [39/40] but to read about they sound far from pleasant. Not only are they dangerous, untrustworthy, and very capricious, but they are repulsive-looking from the way they maltreat their mouths, and their language is for the same reason specially difficult. They speak, not with their ruined lips, but with the back of their throats, so that their words are hardly articulate. But their special charm lies in the fact that they are a very manly race. They have more what Americans call "grit" than most inhabitants of the Southern Seas, and they promise to be as strong for good in the future as they, have hitherto been for evil.

After the usual break for Christmas at Norfolk Island, the Southern Cross re-visited the group. The Bishop was received as a friend, and went to visit the wife of Tuponu, promising to do his very best also to rescue Aqua if he had survived the last few months. This year they ventured to visit Nukapu, where the first man who came on board went straight up to Bishop Selwyn and kissed him. They still wished to avoid all mention of Bishop Patteson, but were willing to welcome another Besopè if not reminded of their crime.

About a week later he was at Saa, and here he found that Aqua, the other Nufiloli man, had not, as they expected, been killed and eaten, though he had had the narrowest escape possible. The very night before the feast had come, and he was sleeping in a hut, guarded, and expecting to be killed at sunrise. Natives as a rule are the lightest of sleepers, but on that night so deep a sleep fell on the guards that they never heard when their victim raised himself stealthily up and proceeded to make his way, first to the door, and then past it to the shore. Here he found a canoe, but there was no oar to paddle it with. So he re-entered the hut, once more passing the guards, took a paddle out of the thatched roof, and passing the sleepers a third time, reached the canoe safely. He eventually made his way to Saa, where Dorawewe took him under his protection and adopted him.

Aqua thought his escape so wonderful that he felt that the God of the Christians had cast his guards into that strange, deep sleep, and was very much impressed by it. It was still not easy to get him back to his island, for Dorawewe liked him and wanted to keep him, and it required the attraction of an extra big axe before the chief would allow the refugee to leave Saa in the Southern Cross.

During his time at Saa, Aqua had been much with Joe Watè, who was the teacher there, and from him had learnt enough Mota to be very useful as an interpreter. As he was willing, it was decided to take him to Norfolk Island before landing him at his own home. A man who had seen the College and its ways, though it might be only for a few days, could tell his own people all about what went on there, and would be a most valuable connecting link.

It was decided to put a teacher at once to follow up the opening for friendship at Nufiloli, and Wadrokal, who had by this time had a quarrel with Bera, was removed from Bugotu, and as usual volunteered for the post of danger in the Santa Cruz [40/41] group. Carrie was willing, too, and the people were friendly to them, and all went well, though, of course, there was no small anxiety in leaving them for months in the power of the Cruzians. This was rather a successful part of Wadrokal's career, and he did good work there, whilst the fact that his ways were always rather consequential suited the Cruzian chiefs, who liked to feel that a big man had been sent to teach them. He was eventually moved from Nufiloli to a larger sphere on Santa Cruz itself, and the only thing to be regretted was that he could not keep well. He was, in fact, getting old as Melanesians count age, and after a few years more he retired with a pension to his own island of Nengone, where he died in 1892. Nengone was now worked entirely by Wesleyan missionaries, so he ended his days amongst Christian surroundings.