THE tragedy of that St. Matthew's Eve drew the eyes of the whole world on Melanesia for a time, and it called out a desire to volunteer for the Mission there in many generous hearts, and especially in those of two young clergymen working in the Black Country. These were the second son of the Bishop of Lichfield and his great friend, the Rev. John Still.

John Richardson Selwyn was the "Johnnie" of the old days in New Zealand, who had played on the warm beach near Auckland with Maoris and Melanesians, and who had always loved the Southern Seas. Like his father and Bishop Patteson, he had been reared at Eton, and rowed in the Cambridge boat against Oxford two years, once as stroke. He was great at all manly exercises, not only at boating, and was a Missionary in every fibre of his strongly human nature. At once on hearing of Bishop Patteson's death he dedicated his life to Melanesia, but he had duties in England that could not be left immediately.

It was very much wished, and at first hoped, that Mr. Codrington, who knew more about Melanesia than anyone else, would consent to be the second Bishop. But though everyone else thought him the right person, he himself was so certain of being the wrong, that he refused, and this being the case, the only thing to be done was to train another man for the post. And though not yet old enough to be a Bishop, it seemed from the first likely that by the time he could be consecrated, Mr. Selwyn would prove to be the right man. The very name of Selwyn was a power in those seas, and the Bishop of Lichfield thought that with his name his son had inherited the gifts which had enabled him to do such good work in the infancy of the New Zealand Church.

In June, 1873, when Mr. Codrington returned from the ordination in Auckland, he brought with him to Norfolk Island Mr. Still, just come out for work in Melanesia. Mr. John Selwyn had, with wife and child, got as far as Auckland, but he had been so ill with rheumatism that it was considered unwise that he should at once expose himself to the damp heat of the islands. It was feared that if he did this too soon an accidental rheumatic attack might develop into a chronic tendency such as would seriously hamper his future work. So though it was a great disappointment, he forewent the pleasure of going the island voyage that year, but when [30/31] Mr. Codrington returned from it he found him and Mrs. Selwyn settled at St. Barnabas'. They received a warm welcome at once, for the sake of their parents, and created a most favourable impression on their own account.

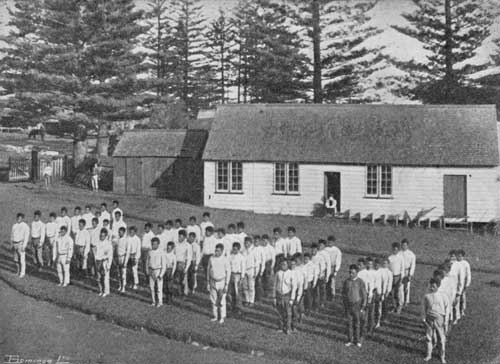

(From a Photograph by Rev. L. P. Robin.)

The house set apart for them had been bachelor quarters, and was reported to be "more like the inside of a work-box than a family residence"; but Mrs. J. Selwyn wrote cheerily of its good points, and managed soon to convert its bad ones. She was no more on the look-out for hardships than her husband.

He, on his side, was delighted with the tone of St. Barnabas' College, which he said reminded him of Eton, so thoroughly had Bishop Patteson managed to inspire his black scholars with high-minded public spirit and the principle of "Noblesse oblige," unlike as were the homes from which they came to those which sent their sons to the real Eton.

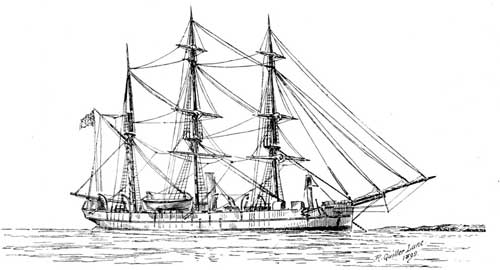

In 1874 a new and more convenient Southern Cross was launched and given to the Mission as part of the memorial to Bishop Patteson. The remainder of the large sum collected was to be expended in a stone church at St. Barnabas', Norfolk Island.

[32] The new vessel was a great boon. Not merely was it bigger and better than any of its predecessors, but it was fitted with auxiliary steam power, so that, not being dependent on wind only, it could get through a much larger amount of work in the same time. This made it possible to take at least two voyages each year--an immense advantage, as it enabled the white clergy to divide their time between the islands and St. Barnabas, without its being necessary for any one person to stay for months on a single island because he could not get away from it. It was often possible for a man to keep well enough for six weeks to be very useful on some island or under circumstances where an enforced stay of months would be too unwholesome and wearying to be risked.

Three-masted, two-topsail Schooner. 180 tons. Auxiliary steam power, 24 H.P. 1874 to 1892. Built in Auckland. Cost about £5,000, of which £2,000 was contributed from a fund collected by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in memory of Bishop Patteson.

It was in this new Southern Cross that Mr. Selwyn took his first voyage amongst the Islands. He had offered himself, full of enthusiasm which never failed him, but when face to face with the undertaking he felt the tremendousness of its responsibility as any good man needs must do. He was conscious of his own shortcomings, and doubted whether, after all, he were the best man for the future Bishop. He was an evangelist through and through, and the life suited him. He loved the boating and [32/33] climbing and the many emergencies which called into play manliness in the special service of God. But he doubted whether he had the same sort of personal liking for the islanders themselves which had made Bishop Patteson able to win so many of them to Christianity. He felt he yearned over them for Christ's sake rather than for their own; and probably he knew the truth about himself; but if so, it was hardly the disadvantage he thought it. It did not hinder his being as thoroughly what Melanesia now wanted as Bishop Patteson had been in his day. Their first Bishop had no home or wife or child to share his heart with them, and his whole being had gone out to them as though he were father and mother in one. But that first stage was over, and when, his probation ended, John Selwyn was consecrated their second Bishop in 1877, he took an ideal elder brother's place amongst them. He had the gift of ruling, and he was also the right person to draw out the powers latent in the men themselves, to develop their self-help, whilst leading them onwards by his own example and encouragement.

Joined the Mission,1873. Second Bishop of Melanesia, 1877-1892.

(From a Photograph by Lyddell Sawyer.)

He was not less beloved than Bishop Patteson or less regretted when he, too, died in the prime of life--worn out with work for the Island Mission. He once told Miss Yonge playfully that he was afraid the "D.D." after his name stood for "Deficient in Dignity," and it was a true word spoken in jest. He was not wanting [33/34] in true dignity, but eager and impulsive in manner, he was not at all the conventional Bishop of civilized society. But Melanesia was uncivilized, and he was the right man for her.

(From a Photograph by Bishop Montgomery)

If there were few striking events, there was much steady growth during the five and a quarter years that Melanesia was without a Bishop of her own. In 1875, Mano Wadrokal had been added to the roll of native deacons. He was an older Christian than any of the Banks islanders, having been baptized when Bishop Selwyn still kept his native home, Nengone, in the Loyalty Islands, under his supervision. He was a man of much force of character and great zeal for the faith, but he had a difficult temper and an unfortunate propensity for seeing the worst side of everything and everybody, instead of the best. But he was nobly ready to volunteer for the post of danger, wherever that might be, at the moment, in which he was encouraged, not held back, by his brave wife, Carrie. He had been a teacher for many years, but his first post as deacon was in Ysabel, amongst the head-hunters at Bugotu. He [34/35] and Carrie did not literally live up a tree, as she had feared she might have to do, for safety. Bera, the chief of that part, was friendly, and they were under his protection, though he himself was still a heathen.

Years before, when Bishop Patteson first visited those Northern Islands, Bera had received him as one king receives another. A stately figure, in spite of his scanty attire, and with a beautiful white cockatoo perched in fine contrast on his brown wrist, he presented the bird to the Bishop as a mark of friendship, and it was, of course, with his consent that a school was opened in his district. It was never the mission plan to run counter to the authority of the chiefs near whom they settled. Besides the danger and discourtesy of so doing, native law was better for the people than no law at all would have been.

The Banks Island clergy were working well, and so were teachers still laymen, such as Edwin Sakalrau at Pek, and Charles Sapibuana at Lango in Gaeta.

Of course, it was a great inconvenience having no Bishop of their own, but it was not the deadlock it might have been in a later stage of mission progress.

The yearly number of candidates for Confirmation was still small enough to be gathered together in Norfolk Island, which could be easily reached by a visiting Bishop from New Zealand; and the few candidates for ordination were all the better for the glimpse of organized Church life which they got by being taken to Australia or New Zealand for the ceremony.

Full as all transition stages are of trial, there was very much to thank God for in the interregnum, now so happily ended.