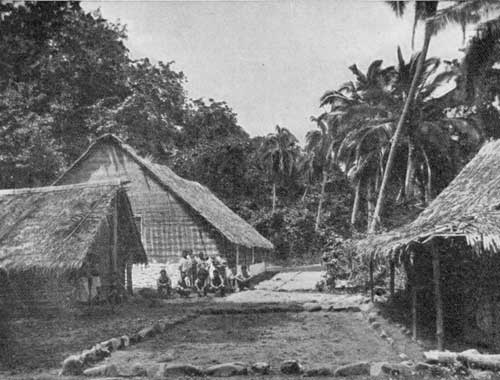

WHEN the College of Kohimarama, near Auckland, was broken up, its name was transferred to a fertile spot on Mota, in the Banks Islands, where a central school and Christian village were established, which in these early days of the Mission did excellent work, although, as St. Barnabas', Norfolk Island, was fully developed, that became so entirely the focus of light that the one in Mota waned in importance.

But in Bishop Patteson's days he saw more fruit of his labours in the Banks group than in any other. Mota is a small island, a single, double-headed volcanic hill, with coral ledges at its base, but it was fruitful and fully peopled, and it was, by the time St. Barnabas', Norfolk Island, was built, more of a Christian island than any of the rest. This does not mean that heathens were not to be found there. There were many, especially amongst the old people, who clung to their old ways; but Christianity had got a firm hold on the island, and Kohimarama had been bought by the Mission, and nobody would have been allowed to settle there who was not friendly to them.

The Banks Islands are a small group, but have been very important in this history of the Melanesian Church, for we may almost call them the Iona of the Pacific. Two only of the group are of any size--Vanua Lava and Sta. Maria [Gaua and Lakona are merely names of districts in the island of Sta. Maria.]--and these have done less in proportion than their smaller neighbours. It seems as if these little steep, well-wooded cones, mostly of volcanic origin, were small enough to get saturated through and through with Christian ideas in a short time, and from them have gone out Missionaries to the other islands in no stinted measure. This is specially true of two amongst them--Motalava to the north, and Merelava on the south of the cluster. Motalava and Ara go together. Ara is a very tiny island, the home of the brothers Edwin Sakelrau, Henry Tagalana, and Demnet.

They were very unlike. Edwin, a man of only commonplace abilities, but of quiet, sensible ways, was married to exactly the right wife, and together for a few happy years they started the village life at Pek, a high point overlooking the shore of Vanua Lava. They soon died, but their influence had been so deep that for years after they had passed away Pek was the specially high-toned and orderly Christian village they had laboured to make and keep it.

[13] Demnet, a much less remarkable man, lived at Pek also, and he and his wife co-operated in a very useful manner with Edwin and Emma.

Henry Tagalad (or Tagalana) was a great contrast to his brother in all ways, except religious earnestness. Whilst Edwin was nearly coal black, Henry was unusually fair for a Melanesian, and for Edwin's moderate abilities Henry had considerable power of mind. He was a source of much both of joy and sorrow to Bishop Patteson in his early days at Norfolk Island, for he was very impulsive, for evil as well as for good. However, Ara has cause to bless him, for he went home to his little island, which is connected with the considerably larger one of Motalava at low water, and from thence for many years Henry superintended excellently the series of schools which fringe its rocky coasts, besides being a parish priest of a high type to Ara itself.

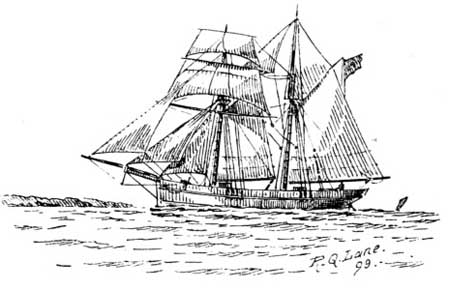

A Schooner under 70 tones. 1857 to 1860, in which year she was wrecked on the coast of New Zealand. Built at Wigram's, Blackwall.

Merelava (or Star Island, as the Spaniards called it, from the spot of light that then hovered in the sky above its volcanic cone) is even steeper than most of the islands, if that were possible. It is the southernmost of the Banks Islands, and is a sort of connecting link between them and the New Hebrides. Hence, in the early days of the Mission, came a pair of twins, the sons of the greatest chief of those parts, Qoque by name, who allowed these, his pride, to go first to New Zealand and afterwards to Norfolk Island. They were very nice boys, were baptized by the names of Richard and Clement, and great things were hoped from their influence in the future. But alas! though far healthier than when in New Zealand, even at Norfolk Island the Melanesians continue delicate and liable to epidemics, and in one of the great waves of illness which swept over St. Barnabas, both the boys died.

Qoque was not a Christian, and his other sons, Marau and Vaget, were then very young (if indeed Vaget was born, which is doubtful since Marau never mentions him in telling the story). He writes his vivid memories of that day of sad tidings, [13/14] evidently engraven on his mind for life: ["The Story of a Melanesian Deacon," Clement Marau (S.P.C.K.).]--"The month of planting was near, and with my father we were chopping away the trees, when in the middle of the day we heard shouts of 'A ship!' and there we saw her, right between us and Mota. Father and all of us ran at once. We forgot our work, and ran straight down to the shore, looking eagerly to see those two twins who had gone away with Besopè. But when the boat came near, though we saw Besopè [i.e., Bishop--Bishop Patteson.] and Robert Pantutun, of Mota, we looked in vain for the faces we knew.

(From a photograph by Bishop Montgomery.)

"Then father asked, 'Where are the two twins?' And when Besopè answered that they were dead, such a weight came down upon all the crowd of people there on the rocks that in the silence it was as if there was no crowd there at all; because everyone was sorry for those two, and we all of us thought much of them and loved them. But presently the whole crowd burst out into wailing for these two, my brothers. And I myself cried loudly for them.

[15] "But before long I composed myself enough to go near the boat and see Besopè. I crept down by my father's side and stepped over into the boat (with R. Pantutun's help), while the crowd was thinking only of its lamentations. Besopè stretched out his arms and put them round my neck, and he untied the handkerchief from his own neck and tied it round me. It was only when some time had passed, and the wailing was quieter, that people observed that I was in the boat. Seeing it, my uncle, was filled with rage, and said, 'Ha! he has taken away these two, and they are dead, and now he wants to finish by killing this one, the last of all.'

Joined the Mission, 1855. First Bishop of Melanesia, 1861 to 1871.

(From a Photograph lent by the Rev. Prebendary R. H. Codrington.)

"He clutched his bow and ran down with a handful of poisoned arrows in his hands, and one already fixed in the bow string, ready to kill Besopè, ready to shoot. Robert Pantutun cried, 'Bishop! they are attacking us!' But Besopè said. 'Wait a bit,' and held up his hand to command silence. And he said to my uncle, who was a great fighting man, 'What do you want? What shall I do for you?' He answered, 'I am angry because of these two sons of mine, and this is the third: you want to make me lose them every one.' So Besopè took out an axe to comfort him, and he was pacified. All this while my own father was sitting quiet, all his thoughts lost in weeping for his sons, whose faces he should never see again; [15/16] and as he wept he cried, 'Alas! my sons! Your eyes, that were the food of my life, are lost and gone from me. Alas! my sons.'

"Then Besopè begged my father to let him have me, and he let me go with him, and so it was. And the sun was sinking towards the West as we rowed off to the ship ; and the people went up the steep paths into the island, weeping as they went."

All who are interested in Melanesians should read the Rev. Clement Marau's little book, for it gives in simple language the best picture we have of the way things appear to the mind of a native lad. It tells of his wonder at what he saw on board--how the man at the wheel seemed to him not a man, but a powerful ghost; of his surprise at English ways; and, above all, at the tender care with which Besopè watched over the little lads, who could "not speak his language nor eat his food."