THE Roman Church constantly reproaches us with our want of Missions, and produces this accusation as one of the most convincing proofs of the sterility of our Church since her separation from the centre of union. It may not be useless to produce here, as one convincing proof against an assertion as unjust as unfounded, the account of one of our Missions. Carried on, it is true, on no vast scale, it is nevertheless touching on account of the zeal and sincerity of our missionaries.

We cannot compare with the Roman Propaganda. But, in that, we must distinguish between true missions, which have their operations among unbelievers, from those which are simply a mischievous proselytism, as all that is done in the East. There the Greek Uniats themselves revolted when it was attempted to force on them the Gregorian Calendar.

The collection of letters, written by the venerable Innocent, Archbishop of Kamschatka and the Aleoutines, to the Archbishop of Moscow, regarding his apostolic labours, now carried on during seventeen years, for the conversion of the savage people in North-East Siberia and American Russia, would afford a series of Lettres édifiantes as interesting as those of which the Jesuits are so fond. To this might be added the picture of the very recent conversion of the Bourial tribes in Central Siberia, with their chiefs and lamas, who had had already a sacerdotal organization.

Again: we might point to the reports of the present Exarch of Georgia in the propagation of Christianity in the Caucasus, on both sides of the chain, where evangelical light makes way, though with difficulty, on account of the warrior spirit of the Circassians. [Isidore, Archbishop of Tiflis, Exarch of All Georgia.--ED.] The Mission to the Calmucks of Astrakhan and the Samoyedes of Arkhangel at the two extremities of Russia, might complete the interesting account. [The writer might have added the most important Mission at Pekin, and that in Finland. In fact the history of Russian Missions would be a work of almost romantic interest. I have been told that Innocent, the above-named Metropolitan of Kamschatka, then only a Mission Priest in the Aleoutine Islands, happened to return to S. Petersburg for help, and was there introduced to the late Tsar. "Why not," said the Emperor to the Holy Governing Synod, "send him back as a Bishop to the scene of his labourer' "Your Majesty must consider," replied some of the old.fssbioned prelates; "doubtless, he is a most excellent man, but he has no cathedral, no body of clergy, no episcopal residence!" "The more like an Apostle," was the Imperial reply "cannot he be consecrated?"--And consecrated he was accordingly.--ED.]

M. de Stourdza had undertaken a work of this kind, but died before accomplishing it. The first volume, sufficiently incomplete, has been published under the title of Blagoviestnik',--Bearer of Good Tidings. It is however a good beginning, which might stop the mouth and open the eyes of those who have left us for Rome.

Note by the Editor. The work of Alexander Skarlatovitch Stourdza has never, I believe, been translated from the Russ. A short account of it may not be without its interest to the reader. M. Stourdza himself, after a life spent in the promotion of religious works, died at Odessa in 1854. He thus commences his preface:

"The annals of Apostolic ministry, and the blessed teaching of orthodox Russian preachers, are not sufficiently known among us; partly perhaps for this reason, that there is nothing romantic in them; nothing that can divert the attention of the majority from the noisy spectacle of the events of a tumultuous world. It is true, in our periodicals, and more especially in our ecclesiastical ones, information is communicated respecting the propagation of CHRIST'S kingdom of grace: but it comes in a fragmentary way, with large intervals in the time of its appearance, so that it cannot produce a full impression on the reader's mind, and is easily forgotten. Meanwhile the oblivion regarding, or incomplete knowledge of, the pious zeal of Russian evangelisers, may give occasion to unfair comments. And, indeed, one meets Russians, orthodox in their faith, who, having cloyed themselves with reading the boastful narratives of the activity of foreign missionaries, impute to their Mother, the Holy Orthodox Church, an imaginary inaction, instead of confessing their ignorance of what she is actually doing.

"In order to manifest the truth, it is necessary and useful to preserve the memory of these blessed and isapostolic labours, undertaken by modest workmen within the limits of our own country, and particularly in the vast tracts of the northeastern continent of Europe and Asia. With this object, instead of any artificial narrative, the editor offers to his readers the sets of Russian evangelists during sixty years, received at different times, and partly communicated by private persons, but mostly contained in the genuine letters of the agents and eyewitneeses themselves, in a consecutive order, without any embellishment or eulogies.

"In all these narratives there is the stamp of authenticity; the joy of salvation there glitters; the zealous advocates of the Orthodox faith will find in them abundant spiritual consolation.

"The editor hopes that the 'Remembrancer' now published, as a collection of truthful narratives, may serve as the foundation of an historical monument of faith, to be erected in our country by the Orthodox Catholic Church."

The title of the book is: Pamiatnik Troudov Pravoslavnich Blagoviestniekov, Rousskich, s' 1793 do 1853 goda. "Remembrancer of the Labours of the Orthodox Russian Evangelizers, from 1793 to 1853."

The first article is, "The Conversion of the Sainoyedes from 1825 to 1830," by the Archimandrite Benjamin, who died in 1846, aged 67: a very interesting end pious journal. Next come extracts from the Travelling Journals of the Archimandrite Macarius, the same of whom we shall hear more in the present paper; then from those of the Archpriest Landyscheff, both concerned with the Missions to the Altai. Next, documents on the Russo-American Church, a singular combination of ideas to us. Then, a series of letters, descriptive of the progress of his Missions, from Innocent, Archbishop of Kamschatka, to Philaret of Moscow, full of the fervour and love of this truly apostolic prelate. Afterwards, extracts from the proceedings of two energetic Missionaries, Peter Levitzy, and Gregory Golovin, and a few other documents of the same kind. The "Remembrancer" is a large handsome octavo of nearly 400 pages.

THE Mission to the Altai, founded in 1830, was at first intended to propagate the faith in the province of Biysk, government of Tomsk; subsequently the ecclesiastical authority, taking into consideration the nomad existence of the natives, and the conversion of some inhabitants of Kouznetzk, extended the Mission to the last named province.

The province of Biysk, inhabited by natives, settled in colonies, who have almost all embraced Christianity, contains 16 villages, of which the nomad population professes the Pagan belief of Schamanism. In this number are 4,896 Tatars, 10,351 Calmucks of the Altai, 2,000 tributary Calmucks: the number of Kirguis, some Mahometans, some idolaters, is unknown: 70 among them have been baptized by the efforts of the Mission. The whole nomad population of Biysk amounts to about 17,500 of both sexes. Before the establishment of the Mission there had been no conversion; at present there are more than 3,000 Christians.

Here there are 6,154 colonised inhabitants, and 9,044 nomads, in all 15,198 souls: the greater part of this population had been baptized before the arrival of the Mission; hut, having no religious instruction, and exposed to continued contact with the Pagan natives, these converts still retained the superstitions of their fathers, living at a distance from the church, and frequently neglecting to baptize their infants. In the Province of Kouznetzk the number of those who are unbaptized, and those who need to be instructed by the preaching of the Gospel, may amount to 9,000.

In the two provinces then of Biysk and Kouzaetzk, the population may be taken at 36,467: of these 23,500 are either not Christians, or have no real notions of Christianity.

A third part of the population of Kouznetzk, usually termed nomad, leads a really wandering existence; the others are fixed in villages, and occupied in the same employments as the Russians. The case is not the same with the non-Christian natives of Biysk, who are solitary and isolated in their dwellings, and shelter themselves under huts made of branches or bark, and sometimes covered with skins. There are only two tribes, the Togouls and Koumandins, who dwell on a kind of plains or moors called oulousse, and almost in a savage state. Those who are baptized form Christian communities, and have adopted Russian manners. The nomad peoples are, for the most part, wretched; they live on cedar-nuts, and the produce of the chase. Those who are best off keep cattle; the Christians are employed in agriculture and the care of bees.

The Pagan inhabitants of the Mongol and Tatar races who inhabit the provinces of Eiysk and Kouzuetzk differ but little in their language, customs, and religion. They admit two principles: Ulguin, the principle of good, and Erlik, the principle of evil; some of them acknowledge the Divine Unity, and worship in Ulguin the Supreme Being, the source of the Spirit of Light (arounemé) : but they likewise offer bloody sacrifices to him and to Erlik, the source of the spirits of darkness (karanemé). After these come the inferior divinities, pure spirits (ok-nemé), impure spirits (pirtak-nemé), who have also their part in sacrifice.

Each Pagan family has its particular deity. When a sacrifice is celebrated, departed relatives are invoked, and certain little idols, adored as divinities, are placed to represent them. Mountains, lakes, and rivers, or rather the spirits which dwell in them, and are their masters, are also objects of worship. The idolaters believe that these spirits obtain possession of the places on which they fell from heaven, and have the power of thus hurting, and even destroying men. The sun, the moon, and fire, figure among their divinities. The most delicious of their meats are offered to the smallpox and to other diseases, to obtain the favour of their hurtful deities. Different religions appear to them to have been distributed by GOD among different people, in the same way as different languages have been. To change their religion is to change their country: it is usual to find a convert hesitate in receiving baptism, from the fear of breaking the ordinary rule of life, and displeasing the government.

The natives of Biysk lead a wandering life on the borders of the rivers Tscharisch, Katoun, and Biy, of Lake Telesk, and the various streams which flow into it. Those of Kouznetzk inhabit the sides of the rivers Tom, Mros, Condom, Tchoumisch, and other small streams. The space occupied by the nomad populations of Biysk and Kouznetzk embraces, from north to south, the space of 1,000 versts, while it is from 150 to 700 in breadth.

This country is traversed by the majestic chain of the Altai: the name of Altai has been given exclusively to the southern part of the territory which stretches from the left bank of the Katoun and the right bank of the Samoulta, as far as the Lake Terletsk: precipices and savage rocks form its ordinary character; the highest summits are perfectly barren, and are crowned with eternal snow. In the northern portion, called Tschern, the soil is marshy; the mountains are less precipitous, and covered with pine-woods; the forests, which abound in this district are thick and impervious. Above the town of Kouznetzk are to be found the nomad hordes of the Tatars of Tschern; and lower, in a locality flatter and less moist, are the colonised natives of Kouznetzk.

Journeys throughout the country, except in the northwest, present countless difficulties; it is impossible to travel in winter and summer except on horseback, and frequently at great risk. In certain seasons, in spring, autumn, and even in a rainy summer, the passes become impassable, on account of the floods. At Tschern, in winter, all communication is cut off by a fall of snow: in the country round Kouznetzk, the only way of going out in winter is on skates. These difficulties render the operations of the missionaries very painful.

To arrive at the conversion of the Pagans, and the religious instruction of the neophytes, the Mission found the necessity of discovering certain fixed stations, at different points inhabited by natives, in which to commence, and from which to carry on, their work. At present there are five such: Oulala, Myuta, Tchemal, Anouy, Macarieff. It has also been found that Christian education could not triumph over the ignorance, the weakness, and the vicious inclinations of the neophytes, unless the latter were isolated from their un- converted fellow-countrymen, and united in Christian communities. The new establishments must not, however, he too far from the habitations of the aborigines, in order to bestow on these, in ease of their conversion, an easy method of joining their brethren. In this way the Mission has founded nine Christian villages.

It was in an oulousse, called Oulala, one hundred versts from Biysk, that the Mission, guided by the Hand of GOD, chose its first residence. This station, on the right of the river Katoun, near the confluence of the Oulala and the Mayma, was founded in 1831. The first head and founder of the Mission, Macarius, who had come to preach the Word of GOD to the idolaters in the province of Biysk, commenced his residence here in 1830. He had visited Oulala on the invitation of a Christian inhabitant, to baptize a nomad Tatar. The favourable position of Oulala, both as regarded the Tatars of Tschern and the Calmucks of the Altai, had deeply impressed Macanus; but he could find no residence there for the winter. At that time Oolala was inhabited by only three Russian citizens, four families of Christian Tatars, and fifteen families of unconverted Teleoutes. At the end of the first winter, he went from Biysk to Saidipsk, a Cossack advanced-post, where he hoped to set up a provisional altar. In May, 1831, he bought at Oulala the cabin of one of the Russian inhabitants. Scarcely had he arrived, when he was informed that, through fear of being forcibly baptized, the Pagan inhabitants were about to migrate to the province of Kouznetzk. He preferred to leave the village, and to betake himself to Mayma, eight versts off, where there were, at that time, ten Christian families. From this place he established friendly relations with the Teleoues of Oulala, and also effected Some conversions among the Tatars of Tschern, and the Calmucks of the Altai, fixing the new converts at Maymn, and in the neighbouring villages. Lodged in the poor cabin of a Christian, at his own expense, and teaching the children of his landlord to read and write, and enduring the most painful deprivations, Macarius undertook, in 1832, to build a house, where he might find an abode, and to which he might add a chapel. His resources were very small: all that he possessed, including his pension as Master in Theology, was employed by him in the colonisation of the neophytes, and in help bestowed on the poorest. He denied himself even the use of tea, and yet the house could not be finished before 1835. In the meanwhile the inhabitants of Oulala had been won over by the sight of so much goodness, charity, and kindness. They at last found out that Macarius ought to inspire no fear, and was worthy of their deepest love and esteem. Touched by his preaching, a large number of idolaters received Baptism in 1834, and surrendered themselves with filial devotion to the Mission. This event determined him to return to Oulala, without, however, giving up his visits to Mayma. Having a sufficient number of church vessels for the Service of two chapels, but only possessing one corporal, destined for S. Saviour's Church, Macarius celebrated service at the two stations alternately, till the arrival of other missionaries, and the present of another corporal, for the second church, that of Our Lady of Smolensk. [There is a very celebrated and wonder-working icon of S. Mary at Smolenek, which Ins become a favourite dedication throughout Russia. According to the use of the Eastern Church, the Liturgy cannot be celebrated without a consecrated corporal, (antiminsion.)--ED.] In 1835 and 1836 all the remaining inhabitants of Oulala embraced Christianity; and those who had at first left that place to avoid the missionary were also converted. Since that period, Oulala has become the principal station of the Mission of the Altai, which thence finds constant communication with the Tatars and the nomad Calmucks. The conversions are frequent: the infidels, like wandering sheep, come to the fold of CHRIST, and after Baptism settle themselves, with the leave of the directors, at Oulala, or in other Christian communities, but especially in the villages where there are already native colonists.

A stone church was erected in 1846, in honour of Pentecost, at the expense of a merchant of Tomsk, Michael Schebaline. In 1848 this church had a parish, a priest, and other ecclesiastics. The instructions of the priest were to spare no pains in working among his parishioners, and to fulfil all the duties gratuitously. After the formation of the parish, the Mission, finding it no longer necessary at Mayma, ceased the house it occupied there to be removed to Oulala. In the latter place a school has been established, together with a reading-room: at the sound of a bell, the boys come daily for instruction in reading and writing; in the afternoons of festivals, the men and women come to assist at the Catechism, or the reading of pious books, or the singing of psalms or hymns. Sometimes the Pagans attend, and take a lively interest in that which they see and hear.

Circle of action at Oulala. The Mission possesses at Oulala a house, where is the temporary chapel, dedicated to the Merciful SAVIOUR, two houses inhabited by the members of the Mission, and a fourth which serves at once as a refuge for the indigent, and an elementary school for young boys; there is also another school for young children of both sexes.

The action of the missionaries at Oulala is principally confined to the east, and has to do with the Tatars of Tsehern, and the tributary Tatars who encamp round the Lake Teletak, by the rivers Tchoumischkan, Baschkouk, and Tscou, as far as the Chinese frontier, which makes a distance of six hundred versts. To the south the Mission embraces the Calmuck hordes, fifty versts off; and to the north the oulousses of the Koymandins, sixty-eight versts off. The missionaries sometimes push their journeys as far as the colonised villages in the province of Kouznetzk; and the far distant dwellings of the Calmucks of the Altai, who wander on the banks of the Koul, the Ab, the Katoun, and other rivers, seven hundred versts off.

Villages dependent on the Mission. The Mission has always endeavoured to colonise so as to reclaim from their vagabond habits its converts. The station of Oulala has under its direction the following villages

1. Oulala. Before the Mission was established, the village contained four families of baptized natives, and fifteen families of unconverted Teleoutes. At present there arc in Oulala seventy houses, inhabited by thirty-two converted Teleoute families, and fifty converted families of the Tatars of Tschern, and the Calmucks of the Altai, both nomad tribes.

2. Mayma, nine versts from Oulala. There were originally in this village ten houses, the inhabitants having completely adopted Russian manners. At present there are eleven, occupied by seventeen nomad families, now converted.

3. High Carracouge, thirteen versts from Oulala: twenty-three houses, inhabited by thirty nomad families recently converted.

4. Low Carracouge, twenty-two versts from Oulala. This village, inhabited by the peasants who labour in the mines, contains six nomad families, recently converted.

5. Bilula, twenty versts from Oulala. The Christian population of this village has been augmented since 1852 by eight nomad families, of whom five yet dwell in tents.

6. In addition to these, there are five other Christian colonies, where ten families of baptized Tatars and Calmucks have acquired houses.

New Colonies of Neophytes.

The Mission of Oulala has founded, in the centre of the nomad and unbaptized tribes of Tschern, the following colonies:--

1. Taschta, twenty-two versts from Oulala: founded in 1854: fifteen families, of whom six live in tents. The Christians at Taschta offered themselves willingly to transport and prepare the wood necessary for a church, where the missionaries could celebrate Divine service, more especially in Lent; but the project has been forced to be abandoned for the present, through want of means. (August 4, 1856.)

2. Kabidja, twenty-six versts from Oulala. Since 1855, six families of converted Koumandins have settled here.

3. Sari-Kokscha, eighty versts from Oulala. A converted native settled himself, in 1848, near the mouth of the Angyrka in Sary-Kakscha, for the cultivation of bees. Two other families joined him in 1852: in the three succeeding years three additional families were settled here by the Mission.

4. Kebezene, 130 versts from Oulala, and twelve from the Lake Teletzk. Three newly-converted families, encouraged and assisted by the Mission, built houses here in 1852 three more have since joined. Those who read these lines may be glad to peruse the following letter from the present chief of the Mission: (Aug. 3, 1856:) "I have just returned from the journey which I undertook to visit the Koumandin settlements. In a space of 300 versts, beginning from Oulala, and following the left bank of the Thy to the station of Macarieff, there are nineteen settlements, which contain 300 dwellings, and 1,220 non-Christian inhabitants. Thanks be to GOD, the number of our Christian colonies increases, and that of Kiltasche has been converted. Here, seven families were baptized on August 1 their houses received benediction. I caused four crosses to be placed at the four corners of the settlement, as a safeguard to the converts, and for the purpose of bringing the means of our salvation before the eyes of the infidels: the latter amount to sixteen families; and some Christian settlers have already shown a desire of settling themselves here, as a favourable situation for bees. Kiltasche is sixty-seven versts from Oulala."

Where the Myuta falls into the Sem, at the left of the river Katoun, the Mission has another station, 130 versts from Oulala, and 150 from Biysk.

This station was founded in 1815. Some Calmuck families of the Altai, converted by Father Macanus in 1845, had not been able to settle in any Christian villages, on account of their numerous herds, for which they found pasturage along the banks of the Myuta. They settled therefore in this place, inhabited at the time by eight families of non-converted Teleoutes, living in wooden huts: these Teleoutes have since become settlers. Father Macarius encouraged the new converts to settle here, hoping that considerable benefit would accrue from them to the non-Christian inhabitants of the adjoining country : the latter were converted in 1855; they learnt to know and to trust Father Macarius, and Baptism followed. The increase of the faithful necessitated the construction, in 1839, of a house, where the missionaries of Oulala sometimes came to celebrate; but the distance and the badness of the roads did not allow them to go so often as the colonists wished. It was clear, however, that active and constant superintendence was necessary in a settlement which touched on the one side a village of schismatical peasants, on the other one of non-converted Calmucks. [I believe, of Popoffchins, the 'Presbyterian' dissenters of Russia.--ED.] These grave considerations induced the Mission to fix some of its members at Myuta, and to erect there an altar, under the invocation of the Blessed Virgin.

At first they lodged in the house of a converted inhabitant; by 1849 they had built one house where the chapel is placed, another which serves as lodging for the missionaries, and a provisional hospital for the sick and indigent.

This Mission comprehends: (a) The Calinucks of the valleys of Mount Altai, thirty-five versts along the borders of the Katoun towards the north, scattered over a space of 350 versts. (6) The settlements of the Teleoutes and the villages of Tscherga and Little Myuta, fifteen or twenty versts off; in the latter villages few Pagans remain.

Villages dependent on the Mission. 1. Myuta, 150 versts from Biysk. It contains sixty- five newly converted families, fifteen of them too poor to have houses; all were nomads, except fifteen families of Teleoutes.

2. Tscherga: and 3. Little Myuta, a colony of Teleoutes, fifteen versts from Myuta; here are ten families of indigenous nomads.

4. In five villages within a short distance, there are eighteen converted nomad families; ten have houses.

5. In 1851 a new colony was formed of new converts, near their tribe's place of encampment at Schibelikta, fifteen versts from the station; there are eight families.

III. STATION OF TSCHEMAL. The third station is at the month of the Tschemal, on the right side of the Katoun, eighty versts from Oulala, and thirty-five from Myuta. Towards the end of 1849, a new missionary, Father John, arrived from Moscow; it was wished to find a new central point for his zeal, and this place was chosen. The selection was justified by the majestic beauty of the site, by the neighbourhood of various tribes of Calmucks and Tatars, and by the success which attended the first efforts of Father John. The Calmucks had to complain of the sectarian peasants, who had ejected them from their abodes, had seized their pasture lands, and had intruded themselves amongst them by violence: it was to the mission, then, that they had recourse, asking to be protected, and promising to abandon their ancient belief and to acknowledge the true GOD. The cries of these unfortunate men touched the heart of Father John, who consented to remain with them, and preferred this abode to one that had been offered to him in the village of Kaja, and where he conld have laboured for the conversion of the Koumandins. The law orders, that the disputes which may arise among the aborigines are to be judged, by word of mouth, by an arbitrator enjoying the confidence of both parties. The Mission, in such a case, never refuses its assistance to the new converts, who thus are habituated to regard the missionaries as their fathers. They follow zealously those practical duties of their ministry, and their devotion finds its recompense in the conversion of the infidels. So it was at Tschemal: thanks to the support of the Mission, the authorities recognised the justice of the complaints made by the new converts, and gave them full satisfaction. The progress of the Gospel was, it is true, slackened by this prolonged strife with the sectarian peasants, who saw with no pleasure the development of civilisation among the nomad tribes: this was one of the greatest trials of the missionaries, but their perseverance surmounted all difficulties. They intend, after completing the religious instruction of these neophytes, to transport the altar dedicated to S. John Baptist, together with the station itself, as too near that of Myuta, either into the province of Kouznetzk, or to the southern part of the Altai, into the valley of Abey, where the nomad Calmucks are very numerous; but this project must depend for its execution on pecuniary means.

Circle of Action. The station at Tschemal possesses--a house, where is the chapel, and where the cells are arranged; another, designed to lodge the missionaries; and a hospital for the sick and the poor. The missionaries have to labour among the Calmucks and the Tatars, who encamp by the side of the Katoun, as well as those by other rivers, such as the Tschemal, the Kouyoum, and the Elikmana, as far as Lake Teletzk, distances of fifty-five, eighty, and thirty versts. They sometimes visit the nomad tribes in the province of Kouznetzk.

Since 1850, twenty-five families of converted Calmucks and Tatars have settled at Tschemal: ten of these, for the most part poor and savage, live in houses; seven more live in three Russian villages, not far from the station.

IV. STATION OF ANOUY. The missionaries sometimes go to visit a new colony of converts formed from 1849 to 1851, near the river Tscherno-Anouy, 150 versts from Myuta. In this colony, at the expense of the widow of a converted Teleoute, murdered by the Calmucks, buildings are erected for the missionaries, where they can lodge and celebrate. Till 1856, the station of Anouy remained in subjection to that of Myuta; but since, in consideration of its distant situation, the large number of Calmucks who encamp in its environs, and the ease with which conversions among them are effected, the station at Anouy has become the permanent residence of some members of the Mission, who have erected there a church in honour of the Ever-Blessed TRINITY.

Circle of Action. The action of the missionaries of Anouy extends over the neighbouring Calmuck tribes, as well as those on the banks of the Pestchana, the Oursoula, the Kane, the Jabagan, the Koksa, and the Abey, as far as the limits of the Semipalatian Province and the Chinese frontier: an extent of sixty versts north-east, and 600 south. More directly to influence this vast tract, covered with mountains, almost inaccessible to travellers, distant from towns and other centres of Russian population, it is much to be desired that another station could be founded in the valley of Abey, or in some similar situation.

Colonies dependent on the Mission. 1. Tscherno-Anouy, 180 versts from Oulala: a converted Teleoute settled here: the Calmucks assassinated him in 1848. The present colony consists of thirty-two families, of which twenty have their own houses.

2. Hyino, on the borders of the Pestchana, forty versts from Anouy: eight nomad families received Baptism here in 1855-6. At the present moment they are preparing for themselves regular houses; and the widow of the murdered Teleoute is building a dwelling at her own expense for the reception of the missionaries and the erection of an altar.

3. Kouyatscha, sixty versts from Anouy; a village formerly inhabited by indigenous nomads. There was in it for some time only a single hut, where a Russian peasant lived. At present ten neophyte families are lodged in nine houses.

4. Koksa, 250 versts from Anouy: an old colony of aborigines: has five neophyte families.

5. In five Russian villages, in the environs, there are ten families of neophytes, of which four have houses.

V. STATION OF MACARIEFF. All the stations of which we have at present spoken are situated to the right of the primitive station of Oulala: the country which stretches to the west is inhabited by tribes of Koumandins, Togouls, and Tatars, in the oulousses on the river Biy, and the province of Kouznetzk. The missionaries have been obliged to be especially vigilant in this direction, to preserve the neophytes from all contact with the sectarian peasants who were colonised here in 1849. A priest, therefore, has been sent into the village of Sayder, where he erected a chapel; but as this place (like the rest, except Kaja), a central point of the sectarians, was not large enough to undertake colonisation on a grand scale, the present chief of the Mission has obtained from Government the concession of a portion of land containing 1395 arpents, on the left bank of the Biy, near the rivers Kaja and Bougatschab, 100 versts from Oulala. It is in this locality that a station, that of Macarieff, has been planted. Eight families of neophytes have already been removed thither; ten more families, very poor, are waiting the assistance of the Mission to follow.

The station of Macarieff has under its direction the following villages:--

I. Kaza, nine versts from Macarieff, with seven families.

2. Pilna, twenty versts, with eight families.

3. Saydy, eight versts, with five families.

4. In four Christian villages, near Macarieff, there are seven families of neophytes.

5. In three oulousses there are for the present left five families, intended to remove to Macarieff.

Circle of Action. The Mission has built at Macarieff a house for the missionaries: a chapel is to be erected and dedicated to S. Macarius the Egyptian.

Their sphere of action extends, to the south-east, from the upper bank of the Biy to the mouth of the Kebezene, over a space of 130 versts; and westward, as far as the oulousses of Eleysk, thirty versts off: to the south it embraces the oulousses of the Koumandins, whose encampments are at a distance of fifty-nine versts, and to the north, the onlousses of the Togouls, the Tschkitims, the Tatars of Techern, as far as Kouznetzk, and even beyond, a distance of 350 versts. Beyond Kouznetzk, the nomad tribes are numerous, and the roads scarcely passable; the ideas of Christianity which have been implanted among them begin to be lost, and the residence of missionaries there becomes an absolute necessity.

One of the greatest obstacles which arises to the propagation of Christianity among the Tatars and the nomad Calmucks, is the fear of being removed into Christian villages, at a distance from their original dwellings and the habitual resorts of their industry. To triumph over these difficulties, the Mission has undertaken to colonise the new converts in the midst of their own tribes: this measure, so salutary for the development of religious instruction and civilisation, cannot really be efficacious, unless the Mission is able to attract into the new colonies bonâ fide cultivators, belonging to the class of Christian colonists, or better skilled converted aborigines, whose habits have become Russian. The presence of such would familiarise the Pagan with domestic economy, and the operations of husbandry: it will be a means of introducing, by degrees, the Russian language, and of ameliorating the miserable condition of the poor heathen, by providing them with healthy food at moderate prices. Besides these, the co-operation of the cultivators would be of great advantage to the Russian Missions in the accomplishment of their principal duties,--such as the introduction of Christian family habits, the establishment of a settled commercial organisation, and outward respect for religious ceremonies.

The colonists might assist the missionaries in the performance of baptisms or funerals; while as it is the latter are scarcely equal to the material requirements of these duties. Those who would like it might be intrusted with the charge of the sick and the infirm. With their help, the missionaries would be better able to remove into colonies the poorer families and the sick, who show an inclination to be taught. The colonists could also second the missionaries in the repressive measures which the latter are about to take, to prevent persecutions and quarrels to which the neophytes are always exposed from the unconverted heathen and from their chiefs.

The number of converts baptized by the mission, not reckoning infants born of Christian parents, amounts to 2,087 of both sexes.

The heathens appear, at the commencement of efforts for their conversion, incapable (from their wretched intellectual development) of understanding the simplest words and the clearest truths of religion. After the enunciation of some maxim, when questioned regarding it, they reply only by a grunt. Patient and gradual teaching before Baptism wakes them by degrees from this mental stupor, developes and enlightens their intellect, the activity of which till then had been paralyzed. Then only, according to the measure of their natural capacity, they begin to seize the truths of the Gospel and the lessons of Christian morality.

After Baptism, the first impression which they feel, as they constantly assert, and as indeed the missionaries perceive, is the calm of conscience. They often say that, in their pagan condition, notwithstanding their barbarism, they were conscious of a sensation of shame whenever a Russian assisted at the ceremonies of their superstition or at an idol feast. As soon as they have received Baptism, they feel that they are on solid ground. Penetrated with the superiority of the belief which they have embraced, delivered from the terrible fear of the demons, who, according to their former idea, rejoiced in their misery here and hereafter, freed from the shameful obligation of a gross rite, the converts are filled with deep calm.

The non-Christian aborigines, especially in the province of Biysk, have little inclination for a life in common; it is with difficulty that they endure any bridle to their passions, since their very meetings terminate in bloody quarrels. Christianity totally changes this savage disposition; once admitted into Christian communities, they readily submit to civil duties and institutions. Who would imagine, in beholding their large villages, now inhabited by a Christian and peaceable population, that the colonists were, before their conversion, savage and sanguinary?

The example of those who have already become accustomed to habits of labour, order, and domestic economy, cannot fail to exercise a salutary influence over the most idle; the latter, by insensible degrees, enter on the same paths, and follow to a certain extent the Christian Rule that they have continually before their eyes. It is no uncommon thing to see a family, formerly incapable of constructing even a hut, and knowing no other occupation than that of hunting, become clever carpenters, and even make their own instruments for field culture or gardening. Having a sufficiency of essentials to existence, their physical condition is healthier, and they are better able to lead a regular life.

Christianity attacks with success, and eradicates the barbarous customs of the aborigines, and more especially those which relate to marriage. Polygamy was universal; wives were divorced on the slightest pretence; new wives taken by caprice; those who had been divorced sometimes re-married; everywhere discord in families, and corruption among children. After conversion, when marriage acquires the character of a sacred mystery, conjugal union becomes closer, and dissolute habits die out of themselves. There exists among the pagans the deplorable custom of exacting a very high price (kalym) for a wife; this price is often not settled beforehand, and being too large for present liquidation by the bridegroom, it gives occasion to quarrels which are handed down from one generation to another, and becomes the germ of irreconcileable fend, the fruitful parents of violence and brigandage. Young girls, not only in childhood, but even yet on their mother's breast, are sold, as betrothed, to old men; or young men, by the arbitrary will of their parents, affianced to aged women. The brother or nearest relative of the deceased has the right to dispose of the widow; he can marry her or can sell her; she is sometimes parted with to the youngest of her husband's relations. In every ease, the children of the first marriage are torn from their mother, and pass, together with the fortune, to the eldest of the heirs. It is his duty to divide the children, especially the young girls, among the nearest relations. Christianity raises woman from this state of degradation, in which she is sold as a beast or an article of property; it re-establishes the natural power of the mother over the children and at the same time, by inspiring them with filial respect, softens their characters, and purifies their morals.

Nothing so developes the intelligence and acts upon the heart of the converts as religious instruction, the celebration of the Mysteries, the exercise of public worship. It is no longer the fear of punishment which hinders crimes; it is the cry of a conscience sanctified by the fear of GOD which reproaches man with the slightest infraction of the Divine Law; where is anything similar to be found among Pagans?

It is found that the new converts are more attentive to Christian instruction, and more scrupulously observant of their religious duties, than the colonised peasants. At least once a year, and (in many cases) frequently, they lighten their conscience by confession, and, full of lively faith, approach the Holy Table. Infants are baptized immediately after birth, and communicate frequently. When a convert falls sick, he at once sends for the Priest, confesses, and receives the Communion from him; to the Priest, again, it is that he has recourse for remedies against his physical sufferings.

In the hour of death, this Christian, scarcely reclaimed from barbarism, calm in his conscience, resigned to GOD'S will, trusting in the mercy of CHRIST, contemplates with radiant joy the eternity which is opening before him, and which has no sorrow nor pain for those that love the LORD. Oh, marvellous gulf, then, between that which he was and that which he is!

The chants of the Church possess great attraction for the neophytes. Some of them, women as well as men, learn with ease to read and write in Russ; they become, in their turn, instructors of the children. They read with pleasure the New Testament, Sacred History, and other books; those that have studied more deeply read the Lives of the Saints in Slavonic, and relate that which they have read to Pagan as well as Christian auditors.

The new converts are generally marked by great simplicity of manner; they arc as fresh in their faith as children. There are, indeed, among them weak natures, induced by the force of habit to resume ancient prejudices, or to give way to bad example; there are even some--but such cases are, happily, rare--who learn with difficulty, at the end of several years, to make the sign of the Cross. But there are also among them intellects of a high order--men who can enter into the sublimest truths of religion. If, generally speaking, the converts are not capable of sounding the depths of evangelical truth, they accept them--and the exceptions are very rare--with fervent faith, and express the deepest disgust at impurity, falsehood, and the absurdity of their former belief.

INFLUENCE OF CHRISTIANITY ON THE YET UNCONVERTED NATIVES. The aborigines who have no notion of Christianity form a very confused idea of good and evil; they arc so imperfectly acquainted with their own nature as to attribute to GOD their worst actions. Seized, for example, in the act of theft, they will say that GOD incited them to it; they believe themselves predestinated to become demons after death; some of them hold that there is nothing beyond this life; and their Priests, the Schamans, boast of being in relation with the most terrible demons, to whom they hope to be joined at the end of their lives. It is not surprising that these idolaters, filled with the gloom of these dark ideas, have frequently recourse to suicide; they choose strangling, as the least painful method of death. Now that Christianity has made numerous proselytes, the Pagans for the most part allow that their own faith is bad, and that the belief of Christians is preferable. Above everything else, the amelioration of the condition of the neophytes surprises them; but they dare not tear themselves from idolatry, alleging their feebleness and want, and, beyond all other things, fearing the vengeance of their demons. It is not unusual to hear one of the unconverted natives relating to others how the True GOD, JESUS CHRIST, became Man, that He might save men from the Spirit of Evil, and from eternal torments; how He was born miraculously of the Virgin Mary; how He suffered to redeem men from sin; how He was crucified, dead, and buried. Some of these same Pagans believe in the Last Judgment, in a Heaven and Hell, and have learned no longer to imagine that the soul is a thread which disappears as soon as it is broken. Their belief in evangelic truth seems only to illuminate them in certain lucid moments; and till the Sun of Revelation touches them, they open their eyes to the truth only to close them again with more obstinacy than ever.

We have seen that the aim of the Mission has been this--to convert the aborigines, to instruct them in religion, to protect them, to facilitate their passage from a nomad state to a laborious and settled life, to ameliorate their social position, by encouraging them in devoting themselves to agriculture, gardening, and cattle keeping; to unite them in Christian communities, and, lastly, to watch over each family and each individual. The activity of the missionaries is not confined to these labours--they themselves teach Russ to the aborigines and to their children of both sexes they have already thirty young boys and twenty-eight young girls who go to school. Orphans, the sick, the infirm, find asylums in which they are boarded and lodged; the missionaries ale obliged to understand physic, to know how to bleed, vaccinate, and the like. To do all this, it is first necessary to study the native language; they understand it thoroughly, and have translated for the use of the new converts, the Creed, [I.e. the Nicene the Eastern church not employing that which we call the Apostles'.--ED.] the Decalogue, certain prayers, the general confession and summary, the preliminary lessons of the Catechism, and some selected portions of the Old and New Testament; they are also compiling, and have made considerable progress in a Dictionary of the Tataro-Calmuck language. Starting from this principle that, in the work of conversion, it is necessary to proceed with caution, to approach the unbeliever by degrees, to win his friendship and confidence, the missionaries seek, above and beyond everything else, to make themselves useful to the aborigines; to accustom them to ask for help in sickness, especially when the remedies of their Schamans are ruinously expensive. They come also to ask for bread, old clothes, &c.; when time was that if even money were given to them, they would reject it. Sometimes Pagans will come to the house to submit their internal disputes to arbitration, to ask for the protection of the missionaries, and to offer prayers, if they are ill.

The Mission is composed of an Arch Priest,--who is its head,--two regular and three secular Priests; seven inferior ecclesiastics, of whom two are monks, four celibate, and only one married; there are also two novices who have recently arrived. Two women take part in the labours of the Mission, in nursing the sick of their own sex, in assisting at the Baptism of women, and in teaching little girls to read and write. In all, the number of the missionaries, their families included, amounts to thirty, nineteen men and eleven women.

The government allows a certain sum for the promotion of the Mission. There are also the pious offerings of charitable persons which help to support it. However economical in their personal expenses, the missionaries frequently exceed their income when the increase of the converts imposes new sacrifices and enlarges the circle of its action.

Without reckoning the personal expenses of the members of the Mission, the following have to be provided --1. The service of five parishes 2. The matters indispensable for the Baptism of the converts. 3. The salary of an interpreter. 4. The vehicles and expenses of travelling. 5. Writing, carriage, and books. 6. The schools. 7. The lighting, and heating of houses, and the hire of a lodging at Biysk. 8. The foundation and maintenance of the different establishments. 9. Medicines. 10. Relief and alms.

Removed, for the most part, from a savage and wretched life, the converts cannot at once be of service to the missionaries. Sometimes they have not the means of removing their families to the Christian Colony; sometimes they want food and clothes; sometimes a whole family has no house, no household furniture, no utensils; or else no instruments of husbandry, beasts, or seed. The Mission ordinarily gives a shirt to every person who is baptised; women receive, additionally, a piece of linen, to replace the cap which they wore while Pagans. The same family has frequently to ask for help more than once; the infirm, the orphans, the incurable, always remain a subject of expense to the Mission,--and whatever be the difficulties with Which the latter be surrounded, it cannot refuse its assistance to those whose misery and Wants it well knows.

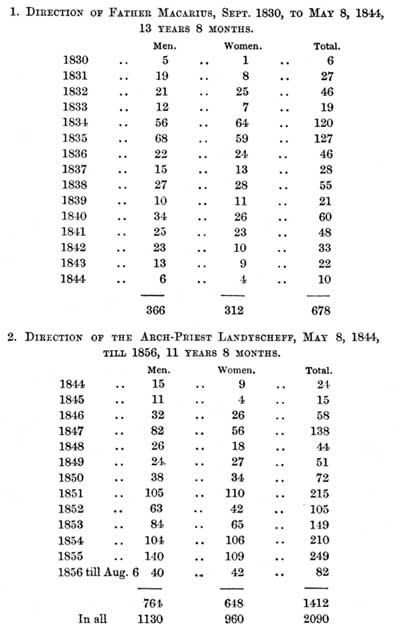

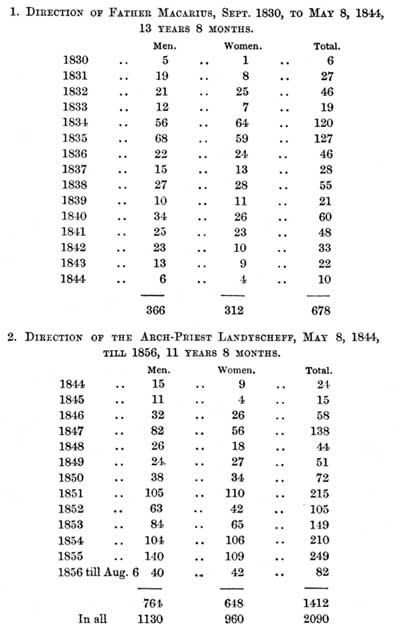

Since the commencement of the Mission till 1856, the annual number of conversions has been as follows:

Project Canterbury