COME with me, and I will take you to a different place from any that you have ever been in before. Never fear; you shall be quite safe: it might be a dangerous scene for others, but (you know) we who relate stories are like magicians, and can go securely where others would perish.

An old, old wood; but not of such trees as are here in England. There is the terebinth; there is the holm-oak, with its evergreen leaves; there is the til, and here and there an aged cedar. All the ground is broken up into little cliffs and valleys; there is no underwood; and here, at the side of a tall steep bank, is a dim, dark cavern. What are these that are basking in the sun,--for the sun streams in between two holm-oaks,--or playing all manner of tricks with each other? They are five cub-lions--lioncels, as the heralds used to call them. Did you ever see such beautiful little creatures? So sleek, so playful, so full of life and spirits. Look, look at that one who has frisked up to the top of yonder little rock, and there stands on three legs, holding the fourth [1/2] down over the side, as if inviting one of the others to a game of play. Ah! I thought so; here comes that other bounding up to the place, and, raising itself on its two hind legs, catches hold of the outstretched paw with one of its own fore-paws. Look how they fence with each other, and then--I wonder how they get so good a gripe without any fingers--the one tries to pull the other up, and that to pull this down. No, fair play, little lion! you are not to take hold with both paws; and that box on the ear was meant to tell you so, I suppose. And look at those others; how they amuse themselves by jumping in and out over each other, a kind of leonine leap-frog. And then, again, that other stretches itself out contentedly in the sun, and purrs so loud that you might hear it a hundred yards off.

A very pretty picture they make, do they not? And it lasts perhaps for half an hour. Now comes something more sad.

Listen! do you hear that short sharp roar in the distance? And now I can catch the snapping of branches and rustling of boughs, as if some heavy thing were forcing its way through the thicker part of the forest. And here it comes. A huge lioness, as ever I saw in my life; quite as tall and long as most lions, though looking thin from the want of the mane.

And what is that she is carrying, and has just laid down before the cubs?

[3] Oh, what a sad sight!

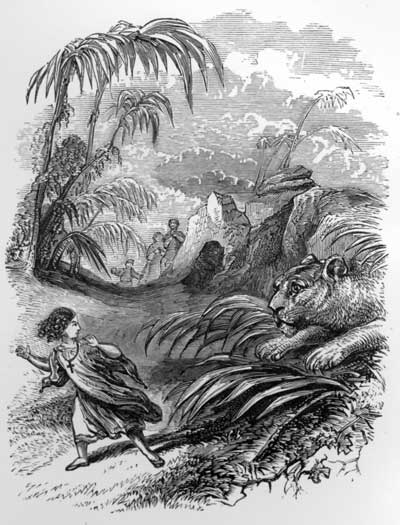

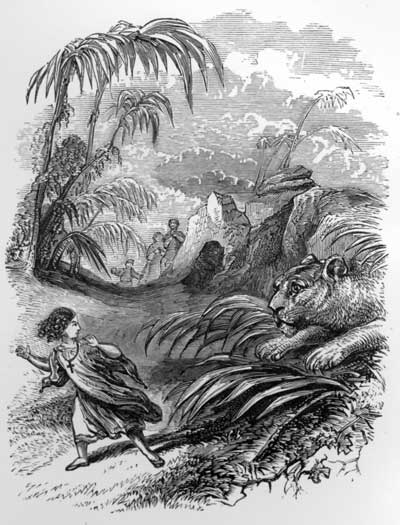

Look, it is a child; difficult at first to tell, in that Roman dress, whether a girl or a boy; but a girl, certainly a girl. Poor little thing! I earnestly hope--and I believe, too--that the shock which the strong lioness gave her when the beast sprang upon her, so stunned her as at once to take away all fear and pain; at all events, that the beast has surely now done its worst, and the poor little frame that is lying in front of the cave will arise no more till the resurrection-day. There stands the lioness, one paw on the body; while her young ones crowd round her as if waiting for their food. But notice this one tiling: round the child's neck, tied by a silken ribbon, is a cross; a rare sight indeed in this part of the world, and in this time of persecution. Ah me! it is a harder struggle yet! Look! the lioness leaves her prey for a moment, and the poor little victim moves. Yes; it is not fancy, you may hear her words, "O Lord! save me! save me!" Do you expect that an angel should appear from heaven, as in the den of lions, and shut their mouths now? No. He knows what is best for her; and all the agony and terror of the moment, what will they matter an hour hence, a year hence, a million of years hence?

Poor, poor little cry! There it is again! "O Lord Jesus! Save me! save me!" Because He has a more glorious crown for her, no. Because [3/4] she is to have her future hereafter with the Innocents, no.

She has struggled on to her knees, her shoulders torn and bleeding cruelly from the teeth of the beast. Alone, in a great wilderness, with a fearful death glaring at her in the face,--THIS is the patience and faith of the saints!

One huge spring--one heavy blow--no fear but that the agony is past, past for ever, and the joy that can never pass has begun.

Let us come away. About that cross and about that child we shall hear more by-and-bye; now leave the lions to their horrible feast.

CHAPTER II. Now I will take you to another scene. This time it shall be one not only that you have never seen before, but that, I suppose, never in the world's history had been seen previously, and never will be seen again.

The wild, wild desert. Night. A kind of camp, lighted up by the blaze of one central fire. Five or six tents pitched round it; fifty camels tethered near at hand. But what are these? certainly not tents, for they are not high enough for a man to get under: certainly not baggage, for they are larger than any baggage that could be carried: these which in a long line have been set down further off from the fire than the tents are? And [4/5] what is the cause of the hideous cries, and howlings, and roarings, that ever and anon burst out upon the night? Instead of my telling you, let us listen to what those men, seated at some little distance from the fire,--the nights are chilly,--are saying to each other. Two of them are soldiers; two seem to me to be slaves; and there is a boy of fourteen or fifteen--he looks like a soldier's servant, or calo, as they call him--a little further from the fire than the others.

"By Hercules," says one of the soldiers, "this is the oddest freight that a caravan was ever trusted with. If a man were to stumble upon us now, he would fancy himself in the infernal regions. Did you ever hear such a noise as those beasts make?"

"I'll tell you what, Caius," said the other soldier, "the old Praefect never did a wiser thing than what we are about now. Many a brave fellow will be spared from crossing in Charon's boat who would have gone over before long but for these."

"Why, both you and I know what fiends those Idumaeans are," replied Caius. "Well, as you say, it was not so bad a thought; and, as I hear, the Emperor was vastly well pleased with it."

"You hear!" said one of the slaves. "Why, I was there; I know everything that happened."

"By Castor, were you?" said the second soldier, whose name was Silurius. "Tell us how it [5/6] was: but stop, it's dry work talking; take a cup of that," and he emptied out of a leathern bottle about half-a-pint of Thasian into a cup of the same material.

"Well to you!" said Xanthias, drinking. "Well, thus it was. I was with the Praefect, Caius Coelius Plautinus--"

"Pshaw, man, you need not tell us his name," cried Caius.

"With the Prefect, then, without any name," continued the slave, "when the Emperor landed at Joppa. And as they were talking over the condition of the province,--Decius always goes to business at once,--he began upon it as they were walking up the quay, and said what a mischief these incursions of the Idumaeans were--"

"To the crows with that beast!" cried Silurius, as an unusually prolonged howl came from the encampment.

"Of the Idumaeans were," repeated Xanthias. "Says my master, 'Sire, I think I could guard its southern frontier, at a very small expense, more effectually than if I had a couple of legions.' 'By Hercules,' says Decius, 'if you do that you will render me the best service I have had this many a day. But bricks and mortar cost more at the outset than soldiers; I know they come cheaper in the long run.' 'I was far enough from thinking of bricks and mortar,' returned Plautinus; 'let us have a couple of score of lions, and [6/7] turn them loose there, and we shall soon see the end of all this bother.' 'They would hunt them down, Coelius,' said the Emperor. ' They might a few, Sire, but they would not kill them off so fast as the young ones came up. That desert must be good for nothing in one way; we might make it good for a great deal in another.' 'Was that your own idea?' says Decius. 'No, Sire,' says my master, like a fool. 'Whose, then?' 'I have a slave from Ethiopia,' answered the Praefect, 'and he put me up to it.' 'Is he alive?' asked the Emperor. 'No, Sire, he has been with the More these three years.' 'I will give orders to that effect,' said the Emperor: and so you see he did."

"Ay," said Caius, "old Magnentius, up in the pity, he that contracts to supply the amphitheatre, was the man that did this job. Fifteen pair of lions he was to furnish; and very fine beasts they are, that I will say."

"Have you any idea what they might cost?" enquired Silurius.

"Only a hundred sestertia," answered the other. [£807 5s. 11d.] "Very reasonable, too. They were landed here at that price."

"And then they serve a double use," remarked Xanthias; "the Praefect sent some three families of Christians there some three days ago; shot them right out into the desert, and left them [7/8] there. Somehow, the spectacles don't answer at Aelia Capitolina." [That is, Jerusalem.]

"No, by Mars!" cried Caius: "those Jews, although they are not allowed to live there, seem to infest the place still. Holloa, you boy! What's your name? You, Lucius, go and see what that beast is making such a noise about." For one of the lions was roaring in so frightful a manner as to disturb the whole encampment.

Lucius rose, and, blushing very much, went off towards the cave.

"Where did you pick up that boy, Caius?" asked Silurius.

"Offered himself to me yesterday," returned the other. "A poor milksop of a boy he is; as thin and delicate as a girl. However, there was no time to be nice in one's choice; I had to be off at once; and I was glad enough to get him. Well, what's the matter?"

"I think he is only hungry, Sir," said Lucius. "Well, then, take him a piece of flesh," said the centurion. And rising, he stuck a kind of trident into a disgusting mass of bleeding flesh, with two great eyes sticking out of it, the head of a slaughtered horse, and gave it to Lucius. The boy shuddered, turned away his head, and seemed hardly able to lift it

"Well, that is a poor milksop as I ever saw," said Silurius. "Thank Jupiter, he seems to have [8/9] quieted the animal; and so I think, centurion, we had better turn in."

"Very well," returned Caius; and in a few moments more, each stretched on the sand within the tent, the Roman soldiers were sleeping as quietly as on a bed of down.

And what was Lucius doing? First, looking round very carefully, to see that no one is watching, he kneels down in the shadow of the tent, away from the firelight, and prays, as they never prayed who worship idols. And if we could look into his heart, oh, what a load of grief we should find there! As well tell you his story now as at any other time.

Quintus Flaminius Turbo was head of the finances in Aelia Capitolina. He had a wife, tenderly attached to him, by name Caecilia; and five children, three boys and two girls, of all of whom you will hear more by-and-bye. Of these, Lucia was the eldest, and little Veria the youngest. In process of time it came to pass that first Caecilia, and then Turbo himself, were, by that good Bishop Mazabanes, converted to the true faith, and their children, then very young, were some of them easily led to it, and some brought up in it. Lucia was about eighteen, and Veria about seven, when Decius began his persecution, the fiercest of all except the last, and the most successful of any. For about the year 240, and ten years on from that time, there was sad laxity all over the Church. [9/10] The world crept in everywhere; Christians were as often found in the theatre as in the church; and therefore when the storm burst forth, it burst forth on those who were sadly, sadly unprepared. But Turbo had not so learned Christ. When the Praefect sent to his house, he quietly gave himself up to the officers, who arrested also his wife and all his children, except the eldest. Lucia happened at the moment to be out; she had gone to visit an old bed-ridden nurse, who lived near the southern gate, and was sitting with her, while the officers carried her father and her family to the Praefect. He, interrogated as to his children, answered truly, that he knew not where the eldest was; and, to make short of a long story, the sentence pronounced was, that he, his wife, and his five children, should be deported, as the phrase went, into the Idumaean wilderness. Then, as the Acts go, Turbo said, "Thanks be to God." And the sentence had been carried into execution a few days before my story begins.

Lucia was just about to leave old Ammonarium, the nurse, when another woman, to whom her family had also been kind, entered the one miserable room, and brought the tidings that the officers were in the house of Turbo. Lucia's first impulse was to return home at once, and to share the fate, whatever it might be, of the others. But Ammonarium, poor despised old woman though she were, had yet wisdom enough to advise her [10/11] young mistress. She reminded her that this would be the one drop wanting to make her father's cup quite full. That it had been again and again ruled that no Christian had a right, by giving himself up uncalled-for to the magistrates, to provoke that magistrate to commit sin: that for her, with a Prefect bent on any wickedness, like Plautinus, there might be dangers which the rest of her family would not incur. And, finally, she prevailed on her to wait till the event of Turbo's examination should be known. "And if the worst comes to the worst, my darling, you can but give yourself up then: wait and see. He may escape, or, more likely still, your young brothers and sisters may escape, and then you would have to be a mother to them." So Lucia agreed: and lest she should be enquired for at her nurse's, returned with the other woman, also a Christian, whose name was Milphidippa. With this poor woman she went back into her wretched room, and there remained hid till news arrived of the sentence passed upon her father. Then, in the darkness of the night, she stole back again to her nurse.

"Now, nurse," she said, "my mind is quite made up, and it will only be lost time to try and dissuade me. My father is banished into that horrible desert, and, somehow or other, I will get there too."

The poor old woman held up her palsied hands, [11/12] and prayed, entreated, conjured,--even got back to her old pagan oaths, "By the Twin Goddesses," and "By Hercules,"--but all to no purpose; the answer was always the same,--"I will go." Ammonarium told her of the impossibility of a woman's making her way even to the borders of the desert, how much more into the desert itself, where the wells were known to so few, where it could be scarcely possible to find a single Christian, and where to trust yourself to the tender mercy of a pagan would be to incur certain betrayal.

Still it was, "I will go; and, nurse, you must help me."

"Well, poor lamb," cried the old woman, stroking her young mistress's head as she spoke, "if I could stir one foot before another I would go with you, and we would get to my lord together, or perish together. But you now go back to Milphidippa, I will set to work and pray; I generally find that I get what I want when I do. You shall come to me to-morrow night, but don't try to come before. I wonder there has not been more hue and cry after you already than there has been."

So, very unwillingly, Lucia went back, expecting to have four-and-twenty hours to wait. But early the next morning a message came from Ammonarium, asking her foster-child to come to her at once, but to keep by the back streets, which the boy who brought the message would shew her [12/13] Lucia, as you may well believe, lost not a moment in setting forth; and very soon, just after sunrise, found herself once more with the old nurse.

"Have you heard anything?" she asked eagerly.

"Yes, I have," said Ammonarium, "if you will go--"

"That I certainly will," interrupted Lucia.

"Well, then, if you will go, and if you have courage for it, I think I have a way which may be possible."

"How, how?" enquired Lucia.

"You have heard me talk of my nephew, Caius, the Centurion?" asked Ammonarium.

That Lucia certainly had, for "my nephew the Centurion" used to be a favourite expression in the old woman's mouth. But she only said, "Yes."

"Well, he came here last night, and told me that he was in charge of a set of beasts, that are to be let loose in the desert as soon as they can be got there,--just as they did, you know, some ten days ago."

"Yes,--and then?"

"And then he wanted to know if I could tell him of any youngster whom he could take with him to help feed them, and do whatever else a servant might have to do; and I told him that I thought I did: do you know whom I meant?"

"Oh, nurse!" cried Lucia, throwing herself on her knees by the wretched bed, and covering [13/14] her face with her hands, "I don't think I could."

"Nor I neither, poor lamb," said the old woman; "but if you cannot do this, which is perhaps possible, how can you make your way by yourself, which is certainly impossible?"

Lucia continued silent for a few seconds, and then said. "What sort of man is your nephew, Ammon?"

"A very honest man for a soldier," replied the nurse.

Another pause--much longer this time--and then Lucia said, "I have made up my mind: I will go. When is it to be?" "He is to set off to-morrow." Now you must remember that there was scarcely any difference between the Roman dress of a boy till he was seventeen, and that of a girl till she married. They both wore the same toga, edged with a purple border, called the praetexta. At the age of seventeen the boy left that border off, and wore what was called the toga pura. When a girl married, she, in like manner, left off the toga altogether, and wore the instita, not so much unlike a modern gown with very large sleeves. The only difference, then, that Lucia had to make was to part with some of her hair, though the long curls behind were left; to put on the little metal ornament called the bulla, which dangled from her neck; and to take a broad-brimmed hat, the [14/15] petasus, instead of the veil. So it came to pass that Lucia, the daughter of Quintus Turbo, Praefect of the Treasury, became Lucius, calo in the little band of soldiers that went with the beasts, and of which Caius acted as centurion.

CHAPTER III. Morning upon the desert. It was in the middle of September. The greatest heats had passed off, but still the sun had power enough to make a few hours' halt, from the fifth to the ninth hour, almost necessary. This was the fashion of the march. There were fifty camels, with a driver to every two. There were five-and-twenty lions and lionesses, ten of the former, fifteen of the latter. Each of them was confined in a separate cage of iron, and at each of the four corners was a strong iron ring. Through these rings poles were passed, and the cage, being then lifted up, was slung by straps between two camels, one before, one behind. The long string of these patient beasts, the bowlings and roarings of the wild animals, as they were jolted by the shambling trot of their bearers, the odd appearance of the cages, covered over with matting, and like gigantic coffins, all this gave a strange, wild look to the caravan, as it wound its way through the solitary desert. The camel drivers walked; Caius, and three or four more of the soldiers, rode [15/16] on horseback; the inferior personages, of whom there were three besides Lucia, were accommodated in the fashion which is now in France called riding en cacolet. "How is that?" you ask. Why thus,--I have more than once ridden so myself. A mule is saddled with a couple of panniers, having very low sides; he also wears a wooden collar, terminating in two points, curling outward high above his head, like the handles of a plough. Your driver stands (in France it is generally a girl) on the off-side of the mule, putting her left hand on the wooden collar. You stand on the near side, putting your right hand on the other handle of the collar. "Now!" she says. And then you both at the same moment have to leap into your respective panniers. It is rather a nice process; for if either of you is much before the other, he or she is very apt to bring the mule down on that side, and to have such a vicious beast as he generally is on the top of you is not pleasant. Well, in this way it was that Lucia had to ride, league after league, through the weary desert.

It was, you see, of the greatest importance to her to learn, if she could, where her father and the rest had been left. She had money with her, as much as H. S. M. C., [i.e. £8 17s. 7 1/2 d.] but she dared not offer any to Caius, it being quite impossible that a poor calo should have any to spare. The thing, [16/17] therefore, was how to get the Centurion's good-will without betraying herself. She had been engaged for her food and for ten sesterces, to be paid when they returned to aelia. But she gained her point on this wise. During the journey, on the third morning, the Centurion, wanting to fasten his impediments, as the luggage was called, better on to the sumpter-mule's back, felt in the pouch of his military cloak for his knife, and, lo! it was not there. Lucia had a very handsome silver-hilted knife, and she offered it to him.

"A very nice article that," said Caius, looking on it with hungry eyes; "how much would you take for it, now?"

"Nothing; I cannot sell it, because it was a gift; but if you have a fancy for it you may keep it."

"By Hercules!" said the Centurion, pocketing his treasure without standing on any further ceremony, lest the offer should be withdrawn, "you are a generous young fellow. To the crows with me if I won't do you a good turn when I have the chance."

The pretended boy thanked him, and said nothing further then; but in the course of the afternoon, finding Caius again near her, she contrived to turn the conversation on the Christians.

"By Jove!" said the Centurion, "they are a queer set, a mighty queer set. I don't mind telling you;--but, do you know, I was once very [17/18] nearly persuaded to play the fool myself, and to become one of them. By Mars! lucky for me that I did not."

"How was that?" enquired Lucia.

"You know my aunt, old Ammonarium?"

"Very well."

"Well, then, you know that she is--" he looked round to see if Silurius was near--"Well, in short, that she is what she had much better not be. I was a lad then, much about your age now,--by Jove! not so fair though,--seen too much out of door's work for that,--when she had a baby,--her husband was alive then,--and surprisingly she was wrapped up in it. Well, one day, it was when there was perfect toleration of Christianity, I happened to step in to my aunt's, as I often did, and found them all going out. 'Where are you going?' quoth I. A little whispering between them,--for there were two or three besides my uncle and aunt,--and then, says he,--poor fellow! he has been with the More these nineteen years,--says he, 'Will you go with us?' 'That depends,' says I. 'Where are you going?' 'Tell him the truth,' said my aunt. 'Well,' said he, 'we are going to have the child baptized.' 'Baptized,' quoth I, 'what's that?' for I was not so well up to them then as I am now. And then they began a long story that, by the life of the Emperor, I could not make out one word of, about being born again, and the old man and the new man, [18/19] and a lot more such trash. However, I went. The place is pulled down now; the Preefect had it down the other day; it stood by the gate of Bethlehem. Then I went in, and there was a kind of pool, and by the pool a Flamen in a long white robe, and two younger fellows with torches by him. Then my uncle and aunt, and a young woman, a great friend of my aunt's,--poor creature, she came to a bad end, a bear made away with her in the amphitheatre,--they all stepped forward, and the Flamen asked them a good many questions, whether they renounced this and believed that. Then he takes the child, and turns it to the west, and blows upon it; after that he gives it to another woman, who looked like a widow, and seemed to belong to the temple; this widow undresses the child, and gives it back to the Flamen. By Mars! it made my blood run cold; I verily thought they were going to sacrifice it then and there. However, he only dipped it in the water three times, and said something that I could not catch. Then they brought another set of clothes, all white, and dressed the child in them; and then they each kissed it, and the priest gave it some honey to eat. Well, that was the end, and very great foolery I thought it. But somewhile after the child died; and when I saw the way that the father and mother, who 1 knew were so bound in it, gave it up, because they said they knew it was happy, by Mars! it was a very [19/20] near point that I did not turn Christian myself. Thanks be to Jove, I am wiser now."

"Have there not been some Christians banished into this same wilderness?" asked Lucia, as calmly as she could.

"I took six the other day, myself," said Caius: "father and mother, and four children."

"Did you?" asked Lucia. "Whereabouts did you leave them?"

"Do you see yonder hill on the horizon?" and Caius pointed across the desert to a peak far away in the south-east, rising sharply like a sugar-loaf. "Out by that mountain--Pallas's Helmet, they call it. Poor things! I'll be bound the beasts have got them before this time."

Thus she had gained what she wanted to know. The plan must be to keep with the caravan as long as it drew nearer to Pallas's Helmet, and then, at the very nearest point, to make her escape by night, and to trust to God for the rest. By means of some very cautious enquiries, in the course of that day and the next, she learnt that the desert was supposed to be utterly uninhabited, but that there were the ruins of several large cities scattered up and down, and that wherever these existed there was said to be water. But no caravans now passed that way; and that, besides the lions and other wild beasts, the whole place was said to be haunted by lemures, satyrs, and fauns. She also learnt that, in all probability, [20/21] their route would lie within three or four leagues of the sugar-loaf mountain; and that, having passed it, Caius intended to advance yet half a day's journey towards the south before he set the beasts free. For two days more they continued to advance steadily towards Pallas's Helmet, but in the last hour of the second day they appeared to have somewhat passed its nearest point, and to be directing their course slightly away from it. When a halt was called, Lucia felt that it must be that night or never.

CHAPTER IV. I have somehow got the skeins of my story a little entangled; a moment's patience, and we will have them right. But I must go back a few days, even before the scene with which my tale began.

You have heard how Quintus Turbo had been deported into the desert, with his wife Caecilia, and his four children, whose names I must now tell you. The eldest, Florentius Turbo, was sixteen; the second, Victor, was fourteen; the third, Aemilius, was ten; and little Veria was about seven. It was about six in the evening when they were told that they must alight,--they had been conveyed on camels,--and in five minutes more they were by themselves, while the caravan, if I [21/22] may call it so, slowly returned to Jerusalem. The spot where they had been left was in the middle of a narrow valley; grey lime-stone rocks towered up on each side to the height of perhaps two hundred feet; and from the backbone of its western range a conical peak shot sharply up against the evening sky. Immediately before them was--not a well, but a spring, which, bursting out from a lime-stone formation, ran for a little distance, and then, swallowed by the bibulous sand, probably re-appeared at some distance in another spring. Turbo knew well enough that this was just the spot to which all kind of wild beasts would come down in the twilight to drink. By a sort of cruel kindness, five long collybi had been left for their support; and by way of parting comfort, Davus, the fool of the party, had consoled them by saying, "You will not be able to eat them before something else eats you."

It was in September, as I told you, and the sun seemed to want nearly an hour to his setting. The first thing to be done was to commend themselves to God, which they did, kneeling by the spring. The next, to fix on some spot where they should be in tolerable safety from the wild beasts, especially the lions, with which these deserts now swarmed.

"Our only hope," said Turbo, "is, by degrees to make our way to Petra; if we can do that, the persecution may not be raging there; or if it is, we [22/23] may still escape notice. Come, dear ones, cheer up; I think, with tolerable care, we may be safe for the night; and we will obey the command of One Who is wiser than we are, and take no thought for the morrow."

"But, Papa," said little Veria, in a most doleful voice, "that man said that we should be eaten up before we had eaten the collybi." She said it so innocently and simply, that her father and mother could not help smiling.

"Nonsense," said Florentius: "did you not hear what Papa said just now, that we might be safe enough for to-night? Don't you believe him more than Davus? But, father, which way do you think we had better go?"

"You, Florentius, get up to the top of this ridge, and walk along southward; I will ascend the opposite side, and keep parallel with you. Then, if you find any place that you think will give us shelter for one night, wave your petasus, and I will come over to you; I will do the same if I find one, and then you must come over to me."

"And we?" said his wife.

"You can just explore round here. We will not be gone more than half-an-hour. I think that we should be tolerably safe anywhere oa the top of the ridge; these animals mostly prowl about in the bottoms. But if we can find any shelter, so much the better."

Florentius, a tall, sturdy youth of his age, soon [23/24] scrambled up the ridge, and they saw his figure in strong relief against the deep blue of the sky. The father was a little longer in ascending his side; and then the two, with a wave of the hand to each other, set out in the same direction, keeping parallel lines, about a quarter of a mile apart. They had not gone on more than ten minutes, and Turbo was already thinking that it was time to return, more especially as a bend in the valley had shut his family out from his sight, when, all on a sudden, Florentius waved his petasus most eagerly, and his father saw that he had discovered something, not visible to himself, on the opposite descent of the range. Not content with waving, the boy threw up his arms, jumped, danced, and played a thousand antics; and the father, rightly judging that he must have made some important discovery, hurried down the hill, ran across the narrow valley, and climbed up the opposite ascent, here very steep.

"Father, father, come quick," cried Florentius.

As soon as, heated and panting, Turbo reached the summit, he saw a ruinous hut, or watch-place; a circular building, reared of rough stones loosely laid together, about a man's height, and with an entrance that had partly fallen in.

"There, father, what do you say to that?" cried the boy.

"That God is very good to us," said Turbo, as tears of thankfulness came into his eyes. "We [24/25] must hurry back to your mother, and bring them up at once. Or stay; we must find some means of stopping up that entrance if it is to be of any use to us. Look, here are plenty of big stones about; do you stay here and collect them together while I bring the others up."

"With all my heart, father. But what do you think this place was for?"

"Scarcely a shepherd's hut," returned Turbo, "for there is not grass enough on the whole hillside to support ten goats: a military station, perhaps. But be quick: you and I will build ourselves in as soon as we have got the others up; and I am afraid of its getting dark before we can finish.--Hark!"

Apparently from the further end of the valley there came a sound which made the hearts both of father and son beat quickly,--the dull, distant roar of a lion.

"Oh, father," cried Florentius, "I dare not stay here by myself!"

"Come, then, with me," said his father; "but you would act more like a Christian if you did what you could up here. If a lion were to attack us, how could I help you? Anyhow, we must be quick." And, scarcely waiting to hear Florentius say "I will stay," Turbo ran down the hill.

He found his wife and her children in an agony of terror; for they, too, had heard the lion, and knew not how soon he might be upon them.

[26] "Never mind," cried the father: "thank God, I can soon put you out of danger. Drink first at the spring; you will have nothing more to-night. I and Florentius had a good draught before we left."

"We shall not have time! we shall not have time!" said Aemilius.

"You will always have time to do what I tell you," said his father. "Kneel down and drink." They did so; and then Turbo, giving two of the collybi to his wife, took the other three himself, and half led, half dragged little Veria up the hill. Just as they reached the top, Aemilius looked down into the valley, and cried out, "Oh, papa, there is a yellow dog at the spring!"

Turbo turned hastily round. "It is a jackal," said he. "He is a sort of creature that would do us no harm, only he means that something worse is behind." As they hurried along the top of the ridge, another, and then a third jackal, came down to the spring; and then they heard the roar of the lion much nearer.

"Oh, my dearest husband," cried Caecilia, as she saw the hut, "how thankful we ought to be!"

"We ought, indeed," he said. "But we have still some work to do; for we must build up that doorway after we are in the hut, or it will not be of much use to us.--Well done, my boy; that I call working like a man:" for Florentius had [26/27] lifted near to the hut four or five-and-twenty good-sized bits of rock.

"Did you hear the lion, father?" he asked.

"I heard him," said little Veria; "and, do you know, there are three such pretty dogs, as if they were all made of gold, down by the spring."

"Now," said her father, "you little ones must get into the hut first of all; and you too, love: you and Victor can help to lay the stones as Florentius and I bring them up to you."

So said, so done. The two young ones were delighted with their new home, as they called it, and the others felt their hearts overflow with thankfulness that even in the wilderness God had provided them with a defence. They worked away in filling up the door, and though they were not able to make their erection half as thick or a quarter as strong as the old portion, still they thought it might do. It was between three and four feet high, when Florentius, having gone to the edge of the hill for a good-sized bit of rock that he saw there, ran back without it, and said, in a low, tremulous voice, "Father, the lion is drinking at the spring."

"Then," said Turbo, "we had better hand in as many stones as we shall want, and finish the rest on the inside."

They were handed in: Florentius, with his father's help, easily scrambled over the barrier; and then, with more difficulty, and not without [27/28] in some degree shaking the structure, Turbo followed him. Then without any great effort they began building up from the inside, leaving interstices between the stones big enough to serve for breathing-places. The rudeness and roughness of the erection mattered little; it was only intended for their occupation one night. As soon as the outside wall was complete, and that was not till it was dusk, the little party within sat down to their supper. They had nothing but the collybi, but the feeling of safety was so dear and so strong, that they all thought that first supper by themselves in the wilderness one of the sweetest they ever tasted.

The moon came up over the desert. Oh how many wild tales rushed into their minds, as the night grew darker and deeper, of voices heard in those solitary places to lure men to their destruction! of sounds as of a great host passing, tramp, tramp, where the children of Israel, sixteen hundred years before, had moved on in their squadrons, according to their tribes!

At length the father spoke.

"Dear ones," he said, "it has pleased God to try our faith by leaving us alone in the uttermost parts of the desert. Well, what saith blessed David? 'Even there also shall Thy hand lead me, and Thy right hand shall hold me.' But see how He has provided for us a lodging even here! See how through His mercy we may lie down, and

none to make us afraid! Now listen to me. It is my purpose to strike boldly, to-morrow, for Petra. We shall be starved if we remain here;--nor could I possibly, if I undertook the journey by myself, return time enough to bring you food, even did I not make one false step, or go one yard out of the way. We must all try together; and then, if it please God, we shall all be saved together; or if not"--his voice trembled a little, but he continued--"or if not, why then we shall all together, I hope, attain that ' house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.' Now take what sleep you can; you will need it for the fatigue of to-morrow, for we must be stirring with the morning twilight."

Commending themselves to the God Who never slumbereth nor sleepeth, they lay down as well as the confined space would allow them, and that night passed over quietly.

Turbo was stirring by daybreak. Well assured that, after this, no wild beasts were in that spot to be dreaded, and bidding his wife in a few-whispered words to keep the children quiet as long as she could, he unbuilt--if I may use the expression--a kind of door, and let himself out. He walked along the ridge, noting as well as he could the place of sunrise, which at that time of the year, so near the autumnal equinox, was to all intents and purposes the true east. It was as desolate a scene as heart could fancy. To his [29/30] right was the glen out of which he and his family had emerged the preceding evening: the only living thing in it a crane--one of that sort with golden plumage and crimson neck--by the fountain; the descent of the hill where he stood; the glen itself; the opposite rise, strewed with great boulders, from the size of a house to that of a tortoise, which many resembled; a little withered grass--the heath in the desert that cannot "see when good cometh;" a few scrubby, leafless bushes, overgrown with silver moss. To the left, a bare, bleak bit of table-land; then a low range of mountains, out of which shot keenly into the sky Pallas's Helmet.

Turbo walked and pondered. He went over the course they had taken from Jerusalem; he reckoned the position of Petra; and he made up his mind that his course for Petra was E.S.E., and if anything, easterly. He guessed the distance at forty-five miles, (but there he was out,--it was nearly sixty,) and he thought that on the evening of the third day this might be performed. Veria, to accomplish this, must sometimes be carried. But then, that chain of mountains! Was he to endeavour to scale them, or to lose time for ease? "God help me," said he, "for vain is the help of man!" However, he did his utmost; he made his best reckoning; and he was not so very far wrong. In about half-an-hour he returned to the hut.

[31] The sky was in a ripple of brown clouds--promising fair weather, and perhaps some wind; their lower edges rich with misty gold, their upper parts swollen, as it were, with the mists of far-off seas, and happier valleys, and distant green woods. This poor blighted spot could send no incense to heaven.

It was but a rude way that the good father had of directing his course. The sky, as I have told you, was cloudy; and he therefore could not exactly tell where the sunrise had been; but he remembered the sunset of the last evening, and contrived by the recollection of that to steer a tolerably correct course to the south-east. The country, as I have already said, lay stretched before him in long, wavy hills, their direction almost due north and south. So you see that the obliquely mounting and descending these dull, stony, barren promontories, made it sufficiently difficult to keep a very direct course. The sun shone out as the morning advanced: the grasshopper shrilled in the valley; the red-legged partridge rose from the hill-side; but besides these there was no sight nor sound of life,--all was desolation and loneliness. Florentius went first, leading the way, scaling one hill after another as if he had no fear that his strength would not hold out; the father and mother walked side by side, generally leading little Veria between them, Quintus Turbo in addition carrying the [31/32] collybi; the two other boys came behind. It was a very fatiguing walk: in some places the turf was so smooth and slippery that it was difficult to climb the hill-side at all; in others the ground was strewed with a kind of scoria, which crunched beneath the feet, and made the walking painful as well as difficult. However, with a good heart, our party kept on till noon, by which time Pallas's Helmet lay further behind them, and they had crossed five of the ridges of which I have just spoken; the ascent and descent of each being, perhaps, somewhat more than a mile and a-half. Though Veria had been once or twice carried by her father, Florentius taking in his turn the collybi, she seemed quite exhausted with the heat and the distance; and the strong man's heart sank within him as he asked himself how, if half a day, and that with so much difficulty, could only perform seven thousand paces, provisions and strength were to hold out for fifty thousand. He spoke cheerfully, however; and as soon as the fifth valley had been entered, to the great delight of all, they saw a clear little stream running in the opposite direction to that which they had left in the morning.

"Here we will dine," said Quintus Turbo, "and I congratulate you all that our afternoon journey is likely to be easier than our morning one."

"Why, father?" enquired Florentius, as the [32/33] whole party sat down on the bright green turf by the stream-side.

"Do you not see," replied his father, "that we have passed the water-shed of this part of the country, so that we must have reached the highest point of its level, and have now comparatively down-hill work?"

"Would it not be well, father," said the boy, "to keep along by the side of this stream, instead of mounting hill after hill as we have hitherto done? It must flow into some river; and where there is a river, we cannot be very far from some human abode."

"I am not at all sure but that you advise well," returned Quintus Turbo; "my only difficulty is this. To Petra we must get before we can be even in comparative safety; and Petra lies, as near as I can tell, yonder way;" and he pointed in a direction considerably to the east of that which the stream took. "But thus far I think we may venture: we will keep along the waterside for an hour or two, and find out in which direction it runs. If it keep straight we shall not lose very much distance in that time; if it turns to the left, we will follow it on; but if, unfortunately, it takes a bend to the right, we must leave it at once."

The children were rejoiced to hear that they should have easier and pleasanter walking in the afternoon. For here, too, there was many a sight [33/34] and sound of life not to be met with in the barren and dry land where no water was; the very same land, by the bye, of which David spoke those words. Here the dragon-fly sported over the little brook; snails with bright-coloured shells crept up the water-reeds; great kingfishers skimmed hither and thither after their insect prey; and the lizard, like a heap of jewels, ran along the sunny rocks, or basked in the sand. Armed with a huge knife, which he had managed to conceal about him before the order for their deportation had arrived, Quintus Turbo sliced half a collybus, and divided it among his party. Truly, after having been so long carried through the sun, the bread was rather dry and stale; but the pure and sparkling water made amends for all. As soon as the meal was finished: "The rest of you shall stay here," Quintus said; "I am only just going to mount the highest point of the next hill, to make out, if I can, how the country lies."

"Let me come with you," said Morentius.

"No," replied his father; "you will want all your strength by-and-bye, and must not waste it now. Besides, you must take care of your brothers and your mother in my absence."

"But you will not be long?" said his wife.

"Not more than an hour," he replied; "and in the meantime do you all try to go to sleep, excepting Florentius: some one must keep guard."

"Very well, father," replied the boy. "Leave [34/35] me your knife, and I will cat some of these rushes down. I have a fancy that I can make some use of them."

"There is my knife," said Quintus Turbo; "take care of it, for we may find it a good friend by-and-bye."

So saying, he kissed Veria, and telling her to be sure and go to sleep, he sprang across the stream, and mounted the opposite hill, and directed his course to a little peak, apparently higher than any which he had yet seen. Clambering up, not without some slight difficulty, to its summit, he found--what he had before conjectured--that from this point the hill country began to die away into a wide distant plain, yielding to the east an almost limitless horizon. To the north, the spurs and buttresses of Pallas's Helmet were, with the interjacent ravines, distinctly visible: to the south, more especially Petra-way, the country appeared more rocky and broken, with here and there a clump or grove of trees. But on the further declivity of the hill on which he stood, there was an object which his first glance had passed over, but which might well fill him with terror.

On a rock jutting boldly out from the hill-side stood, perfectly motionless, a large tawny lion. It might be about a hundred and fifty yards off, and seemed to be gazing on the plain below, as if watching for prey. At present it had clearly [35/36] not seen Quintus; and he felt that the best thing he could do was to get back again to his family, and, without terrifying them by relating what he had seen, to urge them to advance without further loss of time. But, unfortunately, he had descended a little on the other side of the hill before he had seen the lion; and now, in turning to go back, he set his foot on a broken piece of rock, which gave way beneath his tread, and bounded down the hill-side: at first quietly, then with great crashing leaps, passing close to the lion, and so rolling on into the valley. The beast turned round, set up a hideous roar, lashed out with his tail, and seemed as if he was about to charge up the hill, and assault the man. But then, changing his mind, he bounded away sideways; and, as ill-fortune would have it, took the very direction in which our party had to advance.

Terrified and vexed, Quintus Turbo again reached the top of the hill, and saw that, as he had been afraid would be the case, the lion's roar had alarmed his family. They had all started to their feet, and seemed as if uncertain whether to follow Quintus, or to fly in the opposite direction. He beckoned to them to await his coming, and a few minutes set him among them.

"What was that? what was that, father?" cried all the children at once.

The poor wife seemed ready to sink from terror [36/37] as she threw her arms round her husband, and enquired, "Have you seen anything?"

"Since it is God's will that you should have heard for yourselves, dear ones, it would be useless for me to try to conceal the truth from you. Yes, I have seen something."

"And what?" said Florentius.

"That," replied his father, "of which we have been afraid from the beginning,--one of these lions."

You may imagine how terrified they all were, how each in his own way asked what was to be done next, and how the danger was to be avoided. Their father hid nothing from them; he told them which way the beast had taken; and that nevertheless in that direction, and in no other, they must themselves advance.

"Now more than ever," he said, "we must commend ourselves to God, and must put our trust literally in that saying which has so often comforted us spiritually: ' Thou shalt go upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the basilisk shalt thou tread under thy feet.'" He went on, however, to say that, after all, by daytime the danger was not great; and that by night they must endeavour to encamp at a distance from the usual resorts of such animals, and anyhow to kindle some kind of light, than which nothing terrifies wild beasts more.

All hope of sleep that afternoon was out of [37/38] the question; and in another half-hour, father, mother, and children were again on their way towards Petra. You would have seen, had you been there, that poor little Veria kept tight hold of her father's hand, as if that were a secure defence against danger; and yet, nevertheless, at any accidental sound--as when the stream happened to brawl more loudly over a little bed of opposing stones--how she started, and seemed to hear the voice of those terrible beasts of which her mind was so full. Even Florentius, and much more his younger brothers, kept nearer than they had done in the morning to the main body; and the mother, as she leant on her husband's arm, was for the most part silent, lifting up her heart in prayer to Him Who can command wild beasts, as well as unruly men, that whatever became of herself, He would at all events protect her children.

They kept along the side of the stream; and the soft turf and bright green rushes, and sparkling and dimpling water, were a pleasant change after the barren hill-sides of the morning. But distance is distance still; and three hours' walk, pleasant though it were, was as much as the strength of poor little Veria could bear up against. By this time they had reached what appeared to be the mouth of the valley: the hill-banks on either side had died away into the more level country, with, as I have said, its occasional copses and [38/39] scattered rocks. The sun, also, was already getting low, and it was time to look about for a resting-place.

And here a spot presented itself as if it had been created by Him in Whom they trusted to supply their especial need. On the right hand side of the valley from the hill-slope there projected, united to it by a narrow isthmus of turf, a solid mass of rock, perilously, it seemed, balanced on a pointed base, but spreading out and overlapping, as it were, to the height of some five-and-twenty feet. In the soil with which its summit was covered a lime-tree had taken root, which now made pleasant music to the evening breeze, and spread a canopy over the little rocky promontory. Save for the isthmus of which I have spoken, there was no access to the spot; and it occurred to Quintus Turbo that to secure that would be a work of comparative ease. Nothing from below could possibly injure them; if they could collect materials for a fire above, they would be secure.

"Now, then, Florentius," said he, "it must be your business and mine to get together as many branches as we can, and any other material that will take fire, in order to keep off the only enemy we need be afraid of here. First of all, let us all drink as much as we need, for it will not be safe to go down to the stream in the twilight. Then the rest of you must settle yourselves as you best [39/40] can on our rock; and your brother and I will look about for fuel."

Accordingly they all drank; and then, the sun wanting about an hour to its setting, went up to their place of refuge. Early as it was, Veria was heartily glad to stretch herself on the ground, and her mother spreading a palla so as to shield the poor child's head from the slant rays of the declining sun, she was soon asleep. On the barren side of the hill there was a sufficiency of thin, dry grass, and this the boys and their mother collected as well as they could; in the first place for kindling, and in the second for a brighter blaze should any nightly visitor prowl too near their encampment. Florentius came in three or four times, bringing an armful of branches, more or less dry, which he tore down from a neighbouring copse; his father was at work at a greater distance, and when he returned, he returned once for all.

So we will leave them there for the present: for remember that they are but one of the parties whom we have to watch in this same wilderness, Lucia herself forming the other. We must next see how she was employing herself.

CHAPTER V. I told you that as soon as Lucia found that the caravan of wild animals was altering its course, so as to get further from Pallas's Helmet, towards which it had hitherto been approaching, which it did early in the afternoon, she determined that that very night the attempt must be made, if it were to be made at all. Fortunately for her, a halt was called sooner than usual that evening; and you may imagine with what anxiety she watched the night, whether it would be stormy or fair, whether it would be dark or moonshine.

"A very wild country that must be, round Pallas's Helmet," she said to her friend the Centurion, who had shewed the greatest civility to her since the receipt of the knife.

"You may say that," returned he; "few more dangerous in all the Prefecture, However, poor wretches, more than one load of Nazarenes I have set down there before now; and, by Mars, I dare say I shall take many another before I have done."

"Have you ever been to the Helmet yourself?" said Lucia.

"Not I--not to the top of it, that is; but some nine years ago I had to go up the valley on this side of it after a stray camel."

"And did you find it?"

[42] "By Castor, yes,--that is, the larger bones of it; the lions and jackals had taken care of the rest."

"I wonder you ventured there."

"I did not go by myself; I had six picked men with me. A wild place it was, as I remember: such tall, dark cliffs overhead, and such a narrow, sandy valley below. I remember the place where we found the bones, and where I suppose they are now. Cliffs, as I say, this side and that; a palm-tree in the middle; and a very steep hill, almost a cliff itself, in front. I recollect that one of our men told me that was the way by which hunters go up the Helmet."

"Go up!" cried Lucia: "what do they go up for?"

"To shoot wild goats. The skins are worth--at least a good one is--four or five sestertia; and then a pair of handsome horns will fetch a good deal more than that. There is a sort of goat up there that has three horns: I have seen them worked into knife-handles, and the like, at aelia."

"How far," said Lucia, "do you take it to be from where we are now"--(it was then about an hour from where they afterwards halted for the night)--"to this valley of which we speak?"

"How far?" replied the Centurion: "why, one would think you want to turn hunter yourself; and I promise you, you want a great deal more [42/43] muscle before you are fit for that. How far? Perhaps six hours' walk from here."

Lucia saw that she must not venture on any more questions; so she meditated, with very little satisfaction, on the answers she had already received. At last the caravan halted.

The moon was several days past the full, and, therefore, did not begin to rise till long after midnight. Till she had light in the ravines Lucia well knew that it would be useless for her to attempt to leave the encampment: and she knew also that her strength for the future would be well husbanded by lying down as long as she might be able for the present. I have already said that, as far as money went, she had more than was likely to be of any service to her: but some provisions were necessary, however soon she might reasonably expect either to fall in with her own party, (if that were not beyond all hope,) or to reach some human habitation. Not without some little awkwardness, under pretence of inquiring a better supper, she contrived to purchase a collybus,--for which she had to pay about ten times its value,--and a small leathern bottle of Cyprian wine. The place which had been allotted for her to sleep in was of course with the other slaves: but she had preferred lying down in the same shed, or rather tent, which was nightly prepared for the camels: and as the slaves' tent was of the smallest possible dimensions, her companions, [43/44] without too closely scrutinizing her proceedings, were only too glad to get rid of her. On this particular night, then, about two hours after sunset, when it was tolerably dark, and the caravan, except for the occasional roar, howl, or yell of some unquiet animal, was still, she crept, as usual, under the canvas that had hitherto given her shelter. You may imagine how fearful she was of giving herself up to natural sleep, lest she should not be ready at the rising of the moon to begin her intended flight. She had learnt from the Centurion and her other companions that there was scarcely any chance of meeting with wild beasts on the higher parts of Pallas's Helmet; but there was a space of three or four miles to be passed before the high shoulders of the mountain began to raise themselves above the plain. Here, she knew, would be her time of greatest danger: but there was peril every way, and an almost certainty of destruction if she ventured to return to Aelia.

The moon, as I have said, did not rise till two or half-past two in the morning; and after two or three broken sleeps, Lucia, looking out from under the canvas, perceived that there it already was, red and rapidly mounting above the horizon. At the same time, far away in the direction of the mountains, she heard the melancholy howl of the jackals. These she knew that, in themselves, she had no occasion to fear; only it was too probable [44/45] that they were the forerunners or companions of lions. For more than an hour she lay under that wretched covering, terrified at the thought of exposing herself to the wild beasts, and yet miserable in the recollection of how rapidly the moments in which escape was possible were flitting by. It must have been about the tenth hour when, the moon being now some way up the sky, there was a silver streak over the eastern desert which could be nothing but approaching day. That at length decided the matter; for in another hour the caravan would be astir. And so, creeping quietly out from the camels' tent, and burdening herself with nothing except her money in a pouch, the collybus, and one of the camel-drivers' sticks, she stole quietly from the encampment, and started in the direction of Pallas's Helmet, which loomed out in a kind of ghostly haze through the night.

There were no noises of wild beasts now; and a verse came into Lucia's mind: "The sun ariseth, and they get them away together, and lay them down in their dens." And in about half an hour there were clear signs of daybreak. The morning breeze sprang up; the sand-piper twittered from his nest in the wayside bank; every step on the sandy waste grew clearer and clearer. And then, shortly afterwards, the rise of the mountain began: first gently, and, as it were, almost imperceptibly; then by degrees the soft, smooth [45/46] slope of sand shewed here and there a rock jutting through it; then the ascent grew steeper and steeper, and wound its way through a mere gully, the rocks--sometimes bare, sometimes overshadowed with a palm or teal-tree--jutting up on either side. And so the horizon behind began to widen out; and now Lucia could see plainly, but as a mere speck in the distance, the caravan which she had so lately left. It had not as yet moved its place, and Lucia fancied how even at that very moment her former companions might be wondering at her absence, and threatening all kinds of vengeance on her when they should find her again. But the road grew steeper and steeper, the air fresher and brisker; she felt that she was rising above the hot, sultry atmosphere of the plain.

The next question was, in what direction she was to bend her way with the greatest chance of finding any living creature. All she knew was that somewhere towards the south-east lay Petra; and thus much her common sense suggested to her, that her best and safest course would lie in that direction. For I am afraid that she knew even less of the very first details of geography than you, my fair reader,--supposing you to be eighteen or twenty,--might do, if you suddenly found yourself set down in such a desert as she was then emerging from. I fear that it never struck her that, in such a tract, human beings [46/47] would be more likely to be congregated wherever there should appear the most abundant supply of water; and as to mountain chains, and the general direction of valleys, and watersheds, and upland levels, they gave her no tangible ideas of the best method of proceeding. And what was more immediately dangerous, I do not think she was aware that, in a country overrun with wild beasts, springs or streams were the most dangerous of all places in the evening or morning twilights.

But there is one wisdom above all wisdom which Lucia did possess, and which in those times of persecution few Christians were without: I mean the wisdom of prayer. When she prayed, it was not a half-idle, half-in-earnest mention of something that it seemed desirable to have; but a stedfast determination that what she intended to ask for she would not cease demanding till God gave.

And she did pray. She asked that she might be directed in the way best for her; and which that way was, whether in the direction of Petra or towards any other spot, she knew not at all. She could not even tell whether her father and the rest of her family were still in this world, or in the better Land of the Living. In the meantime, her path was so far clear that there was no possibility of turning either to the right or the left from the gulley which she was ascending. [47/48] And so about the second hour of the day, when she had walked continuously for a longer time than ever before in her life, she sat down under a juniper-tree, where a fountain welled out of the earth,--the same which, after many a winding, supplied the little pool of which I told you not long ago, where the family had quenched their thirst, and where the jackal had afterwards drunk. So, eating a piece of the collybus, and scooping up the water with her hand, she sat down for awhile in. the shadow,--for the sun was already gaining some power,--and, tired out with the vigils of the preceding night, fell asleep.

CHAPTER VI. The poor family in the desert kept on a pretty constant course during the whole of their third day. However eager they were to proceed, they were forced to rest during much of the morning: but they followed the streamlet during the entire course of the afternoon. And just as twilight was falling upon the earth, just as the shadows of the western hills were shutting out the whole eastern side of the valley from the reflected light of the sunset, they came down to the end of the dale which they had so long been passing through. Here buttress after buttress of the hill country died away; this great valley sloping from the [48/49] west towards the east, and receiving the mouths of all those--through one of which our party had come down--which ran from north to south.

It was manifestly impossible to advance further that day. Even the boys were tired; little Veria was ready to drop with fatigue; Caecilia herself was utterly exhausted. The question was, during the hour of light which remained, what position to take up with a reasonable chance of safety for the night. And then came that other even more fearful question, "What about provisions for the morrow?" I confess that the heart of Quintus almost sank within him. Their provisions were now reduced to that one night's meal; so far as appeared, there might be no human habitation within leagues of where they then stood; and this larger watercourse, into which the different valleys emptied themselves in the rainy season, was the exact place where lions might be most reasonably looked for.

As on the preceding evening, the party of wanderers threw themselves on the green grass by the stream-side; but far more with the feeling of utter hopelessness, far more with a knowledge that a stranger might say, "Where is now their God?"

Except a very small piece of the collybus, all was now devoured; and even that all afforded a very, very scanty meal. The younger ones had scarcely finished, when Quintus, rising, said, [49/50] "Florentius, you stay with the rest; I am just going up yonder hill, that I may see what place of hiding we can find. I do not think that we need be afraid of wild beasts as yet; but if they were to come I could be no protection to you; and I am sure you are all too tired to take any unnecessary steps. If I see anything that makes it worth our while to ascend yonder hill, I will beckon to you when I am at the top. You have a good eye, Florentius; do you therefore keep it fixed upon me."

The father set off; and as he went, he, as old Homer would have said, "devoured his own heart." He struggled up the hill, eager not to lose an unnecessary minute of light; and found, as soon as he reached the summit, that again God had been better to him than his fears. At the top of this hill there was a considerable extent of high table-land: but about two hundred yards before him, in a little circular valley, there grew five or six holm-oaks; very aged, with boughs very much twisted, and apparently the poor remainder of a much larger host, if one might judge from the scattered stubs and stumps that grew about them. Most earnestly thanking God for what he beheld, Quintus rushed to the brow of the hill, and vigorously beckoned to the party below. Then, after seeing them in motion, he went back again to the valley in order to satisfy himself which of the trees would yield the best [50/51] shelter for the night. In a few minutes all were once more together.

"No fear for to-night, my pets," said the father; "we shall all sleep as safely as if we were in Aelia." And he pointed out to them the ilices.

But though the means of safety were at hand, it was not so easy at first to avail themselves of the refuge. Florentius, however, easily climbed the tree which his father thought likely to be the best hiding-place. Little Veria, lifted as high as he could by her father, was secured by her brother in a fork of the tree; and then the others by turns; though it must be confessed that Caecilia's ascent was not achieved without considerable difficulty. Last of all, Quintus himself climbed up: and oh, how his heart burnt within him, to see all that were dear to him for that one night safe, whatever might happen!

An old, gnarled, knotted tree it was; and the boys without very much difficulty secured themselves for the night, so as to be able to fall asleep without much danger of toppling over. Veria, who already could scarcely keep her poor little eyes open, was tied to one of the safest forks; and then Quintus shewed his wife how best to dispose her weight so as to sleep most securely. By the time this was done it was nearly dark. One by one the stars came out over the earth; and after midnight the moon arose in the unclouded east. [51/52] With moon-rise the howlings of the wild beasts began in the valley, and occasionally came that most fearful roar of a lion which would effectually have banished all sleep in a place of less security. Nevertheless, the younger boys and Veria were so tired out that they did sleep: but to the others it soon became manifest that one lion, at least, if not more, was ascending the hill. Yes; nearer and nearer came the sound: and presently Caecilia spoke.

"It seems to me that I have never known what it was to feel thankful all my life till now. Think what it would have been had we been exposed here without any shelter, and not knowing but that the next moment any one of us might have been carried off!"

"Well, mother," said Florentius, "I for my part will never believe that God would thus have preserved us twice, if He had meant to destroy us after all."

"And a very good argument too, my boy," replied his father. "I remember when our good Bishop Mazabanes spoke to us of Manoah's wife, how by her faith she encouraged her husband, that so much having been done for them, so much more must of necessity follow."

"Oh, mother! mother! what is that?" cried little Veria, waking up, as a fiercer and nearer roar than any before made all the party start. "Never mind, my pet," said Caecilia; "the [52/53] wild beasts can do us no harm here. God has taken as much care of us as when we were in our own dear old house at Aelia."

The moon, as they spoke, began to peer over the summit of a distant hill. But it was no reflection of her rays which shewed four bright phosphoric lamps of fire at some little distance from the tree where our family had taken refuge. Florentius was the first to point them out.

"Look, father!" he said: "what is that?"

Half in the shadow of the tree, half in the moonlight, the strong, black shade falling like an heraldic bar, and 'debruising' their backs, stood a great lion and lioness. The lion, with his mane, half tawny, half sandy colour, just tinted by the moonshine; the lioness, standing by him, shoulder to shoulder, and purring for very joy of her expected prey.

Although feeling perfectly secure,--for the lowest branches of the tree were far beyond any lion's leap, and the accidental projections and holes in the bark which had given a hold to the climbers' feet were of no assistance to such an animal,--yet it was impossible to look on these monsters without trembling. Caecilia passed her arm round little Veria's waist, who for her part hid her face in her mother's bosom. The beasts came under the tree, looked up, and roared; but, with all the pride of their own [53/54] species, would not attempt a leap which they knew to be beyond their power. Some little while they thus remained; then their soft, noiseless, padded footfall passed over the sand, and they went down the hill, probably to drink at the stream.

Quintus examined again, by the light of the moon, which now shone strongly in amidst the foliage, the safety of all his party; that their bindings to the tree could neither give way nor break. And having done this, he, with the others, said the ninety-first Psalm, (the ninetieth he would have called it,) and so he commended himself and them to God's care during the rest of their sleep.

But, behold, when the rising sun aroused the whole party for good, they found that, secure refuge as their tree might afford, they were for the present confined to it. Of the lioness, indeed, they saw nothing; but there sat the lion,--or rather, there he couched, as they say in heraldry,--with his mouth leaning on his extended paws, but with his eyes steadily fixed on his expected prey. What possible hope was there, after all? For although Quintus well knew that no very long time could elapse without the perpetual fever of the lion forcing him to drink, yet the stream was at so comparatively short a distance that to make their escape in the interval would be worse than [54/55] hopeless. So again I say, what possible hope was there that these prisoners could escape? [What follows was suggested to the writer by the authentic tale attached to an aërolite preserved in the Hôtel de Ville at Angers.]

And to explain to you how they were released I must take you far away out of this world;--I do not mean into the land of spirits, but into a part of creation infinitely removed from us. You know how wise men tell us that, in all probability, there was in the planetary system, between Mars and Jupiter, a planet which has long since been broken up, and the fragments of which not only formed the little asteroids which are constantly being discovered, but also those masses of stone which have occasionally, coming within the attraction of our earth, fallen upon it, and of which many are preserved in the museums of Europe. One such had been for many thousand years revolving round the sun till the hour came in which its appointed work was to be done; and that hour was now.

It was a weary, weary time that the poor prisoners waited in the prison of their tree, almost as sorry now to have been induced to take shelter in it as glad on the preceding evening to have found harbourage there. Granting that their enemy, after many hours of watching, took his departure, their food was already gone, and to walk very far without refreshment of some kind [55/56] would be impossible for the children. Every moment of imprisonment diminished their miserable hopes of final escape; and Quintus had seriously meditated whether it would not be better for him to sacrifice himself in order that the others might, at least for the present, be set free. But then he remembered, if with him their chances of reaching Petra were so small, how impossible would the effort be without him. But you know the proverb, "When Israel is in the brick-kiln, then cometh Moses" and so it was now.

The sun had risen most uncloudedly, and the sky remained bright and blue till about the third hour. But about that time a thin, grey haze began to float up through the air, and the light was such as you see on a cloudy day when there is a very great but not total eclipse. Terrified as they all were with the present, and anxious for the future, they were not unsusceptible of this strange atmospheric influence; and, "What singular weather!" or, "What a strange haze!" had been repeated three or four times in the course of that morning. It was drawing near to the fifth hour, and still the lion kept watch, and still the thoughts of Quintus grew more and more gloomy, and still the children were more and more impatient for their release from imprisonment and hunger.

On a sudden a strange, mysterious sound, like the vibration of the wind on a stretched cord: it [56/57] grew louder, shriller, fiercer; there was a roar, as of thunder; and then the whole mountain shook as with an earthquake; sand, broken bits of rock, and pebbles were driven about as by a whirlwind; and then for a moment a dreadful silence, more terrible than the uproar. The first articulate sound was the outcry of the younger children; then their father, who for half a minute had himself been unable to form any idea as to the nature of what had happened, tried to encourage them.

"Now, Florentius," he said, "it will be quite wicked to doubt what you said yesterday, that God must mean to bring us safely to our journey's end."

"But what is it, father?" asked Florentius, in a very trembling voice, though professing to be perfectly calm and collected.

"Do you not see," replied Turbo, "that we are set free from our present danger? Look, my children, the lion is dead; one of those things that happen about once in a century has happened now."

"How do you mean?" enquired Caecilia.

"Have you not heard," said her husband, "of those stones that sometimes fall down from the sky? Look, there it lies; it is just as if God sent it here to this very end, that we might be set free."

So saying, he began to descend the tree till the [57/58] children stopped him with their cry,--"But, father, are you sure that he is dead?"

"You may be quite satisfied about that," was his reply; and he was presently at the spot. The mass of stone,--an iron stone to all appearance,--irregularly shaped, but perhaps two feet square, had buried itself half its depth in the ground; first apparently smiting the lion upon its shoulders, had absolutely dashed it in pieces, and had then pulverised the hard rock all around. Quintus Turbo next looked round in all directions for any traces of the lioness, but he could discover none; and hoping that she might have been terrified from the spot, by the shock which had been that of an earthquake, he assisted his family to descend, and they were presently in safety again at the foot of the tree. And here I must leave them for awhile, in order that I may go back to Lucia.

CHAPTER VII. I left her sleeping by the pool where she had breakfasted, and she slept on till early in the afternoon. Then waking with a feeling of terror that she had overslept herself, and a worse fear when she remembered what was the actual case, and how little she knew where to go, she resolved to pursue the track which she had been taught to look on as that which led to Petra, and [58/59] to make the best of her way, refreshed as she then felt, till nightfall.

I suppose, looking at the map, that she was then about twenty-four miles from her family: they now being nearly south of where she was. You can hardly tell what a dreary thing it is to walk, hour after hour, in these vast solitudes; how the mind gets stupified with the sense of its own helplessness; how fearful the thought is,--If anything should happen to me, here I must leave my bones to whiten; the vulture that I hear screaming over my head would devour me before the breath were out of my body, and perhaps no human eye would ever see my remains.

All this, and much more, Lucia thought; and as the afternoon advanced, and she grew more and more tired, so much the sadder grew her fancies: and when at length she sat down under the shade of a solitary ilex, she felt as if she should be glad if she might there go to sleep, and never again wake in this world. She was refreshed by food, however, and she had with her (as I should have told you before) a flask. This she had filled at the spring in the morning, and so she now had a sufficient supply for the time. Indeed, had she only known it, she had done very well; she must have walked fourteen miles since her first halt, and of these, ten were in the right direction.

When she again attempted to continue her [59/60] journey, she began to feel how stiff her limbs, unaccustomed to that exercise, were becoming, and speedily found that she should only be able to do a very little more that night. By-and-bye the sun went down behind one of the ridges, and the shadow, first settling on the valley, gradually climbed higher and higher, till it covered the whole opposite side. Night came very fast on.