The Syrian Christians: Narrative of a Tour in the Travancore Mission of the Church Missionary Society

[Full particulars of the present state of Travancore will be found in an interesting work entitled The Land of Charity, published by Messrs. Snow, Paternoster Row.]

THE Travancore Mission is divided into two districts, North and South, each under the charge of a resident missionary, who superintends the native pastorates. The character of the people, and the nature of the work, is much the same in both districts. In both there are numerous Syrian churches. Side by side with these are congregations of Syrians, who have left their Church and joined ours, and whom we now distinguish as Syrian Protestants.

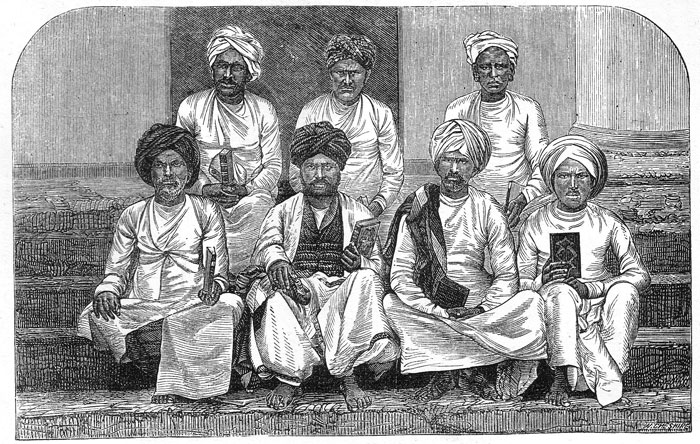

SYRIAN CHURCH--TWO CATANARS IN FRONT. Everywhere on the outskirts of each central organization or head station, where the native pastor resides, there are also two or three congregations of slaves.

The work among the slaves is of comparatively recent date, and forms a most interesting feature in the Travancore Mission. The first efforts were made about 1850 at the instigation of Mr. Ragland, but they did not meet with much success (so bigoted and prejudiced were the surrounding heathen Nairs, and even Syrians also, and opposed to any attempt to raise, or even instruct, the poor down-trodden despised slaves), until within the last ten or twelve years, which have witnessed a most remarkable ingathering of converts.

The number of Christians in connection with the Travancore Mission [511/512] has risen in this time from 7,919 to 14,490, and nearly all of these have been from the slave caste--the accessions from the Syrian Church having almost ceased now that it has begun to reform itself.

These slaves, like the Helots of Sparta, were evidently the original inhabitants of the country, previously to the great Aryan or Scythian immigration, which took place, as philologists and Sanskrit scholars tell us, about 2,000 years ago, when the Sanskrit-speaking race, called Hindus, because they came from beyond the Indus, or Sindhuh (lit. black river), took possession of the whole country, and, as in the case of the Saxons in England, drove back the former inhabitants to the forests and fastnesses of their native hills, and reduced the weaker people of the lowlands to the position of serfs or bondmen.

There are thus two classes of Aborigines or non-Aryan races in India--those which inhabit the hilly tracts, as the Santals and Gonds and Bheels, who retain their own language and remain a perfectly free people; and others, like the Mângs of the Deccan, or the Malias of the Telegu country, or the slave people of Travancore. These last have become so completely absorbed into the Hindu community, that they have lost not only their independence but also their former language, and to some extent their old religious beliefs also--almost everything, in fact, but their distinctive physiognomy, the preservation of which is simply owing to the fact that they are regarded as outcasts, the very scum and dregs of society, and that none, even the lowest of the Hindu scale, would dream for a moment of intermarrying with them. They reside in miserable mud hovels, built on mounds amid the rice swamps, which they are compelled to cultivate for their Hindu or Syrian masters, receiving as their only wages a scanty pittance of grain, so insufficient as a rule for even their slender wants, that they are driven to theft, and make it a practice to enter the neighbouring plantations at night to steal the cocoa-nuts, or plantains, or roots. As a natural consequence they are sunk in the most brutal ignorance; for days and weeks together, at certain seasons, they have to stand in water up to their waists, and so rife are diseases of all kinds among them, that they seldom live to old age.

The slaves were formerly bought, sold, or mortgaged, just like the land on which they lived, or as the cattle and other property of their owners. No wonder that to such a people the Gospel has been good news indeed. It offers them, first of all, deliverance from the fear of the devil, of whom they stand in the greatest terror; their whole religion, in fact, consisting of various rites and sacrifices performed to avert the anger of the demons supposed to inhabit different places. Next, it procures for them their just rights as human beings, which Hinduism and corrupt Christianity has denied them.

[513] As one might expect, the moral standard and spiritual tone of such people, even after they become the professed followers of Christ, is not very high; still there is a marked change, which even their heathen masters are ready to admit.

"Sir," said the head man of a Syrian village one day to B., "these people of yours are wonderfully altered. Six years ago I had to employ clubmen to guard my paddy [unhusked rice] "while it was being reaped. Now, for two or three years, I have left it entirely to your Christians, and they reap it and bring it to my house. I get more grain; and I know they are the very men who robbed me formerly."

Another day, as a native catechist was discussing with a heathen Nair the nature of human responsibility, he illustrated his remarks by referring to the habits of the slaves, who were accustomed to lie, cheat, steal, &c. The heathen at once interrupted him, saying, "No, the slaves do not lie, or steal, or get drunk, or quarrel now; they have left off all these since they learned your religion."

I visited some eight or ten of these slave congregations, and was greatly pleased and interested by the simple earnestness of the people; their willingness to contribute--far more largely, in proportion to their means, than their Syrian neighbours--to the building of their churches and maintenance of their readers, as also by the remarkable aptitude shown by many of the children in learning to read. I think there is little doubt that another generation will find many of them quite on a par, as regards knowledge and intelligence, with the Christians of higher castes. Care has to be taken to keep them from getting puffed-up by their elevation,--especially now that, by an order of the Native Government, all slaves are declared free in Travancore, and many other of their civil disabilities removed.

The movement is, however, a very hopeful one as well as a very remarkable one, and it has done a world of good to the somewhat indolent, selfish, and apathetic Syrians, who were quite content to receive the Gospel and education and Christian ordinances at our hands, but would not contribute a farthing towards it themselves. Now the zeal and liberality of the formerly-despised slave converts is beginning to put them to shame,--and, what is better still, the employment of Syrian (I use the word Syrian here as generally elsewhere, to denote nationality or caste, and not religion, for our agents, though Syrian in origin, are Protestant in creed and belonging to our own Church) catechists and readers, to go among these people and minister to them in spiritual things, has tended wonderfully to break down the barriers of caste prejudice, which formerly existed between the two races, even when both formed a part of the Christian Church.

As regards the actual Syrians themselves, I saw much that was encouraging, and calculated to give good ground for believing that a [513/514] real spiritual reformation was going on amongst them. True, the catanars, or priests, are still, as a body, deplorably ignorant, and care for little more than a decent performance of the duties attached to their office and the saying of masses. There are, however, some noble exceptions, whose zeal and earnest efforts for the spiritual improvement of their people is beginning to stir up even the more careless and lazy among their brethren. One whom I met and had some encouraging conversation with, has translated the Syrian Liturgy into the vernacular Malagalim, from which are omitted nearly all the prayers that a Protestant would take exception to. The Malagalim Scriptures, translated by our Missionary, Mr. Bailey, and printed by the Bible Society, are now read in almost every church; and several of the catanars have mustered up courage enough to expound and preach. The same catanar mentioned above has got his people to subscribe and build a little prayer-house, or chapel-of-ease, on the outskirts of the village where he lives, some two miles away from the nearest Syrian church, to which the people may come on Sunday afternoons and read the Bible together and have it explained by himself or one of his brother catanars. The building, composed almost entirely of wood, reminded one almost of a Swiss chalet, it was so tastily carved in front, and altogether so neat and good. At the gable end, above the entrance porch, two texts were inscribed from the Malagalim Bible: the first, "There is one Mediator between God and man,--the man Christ Jesus;" the second, "God is Spirit, and they that worship Him must worship Him in spirit and in truth." One could hardly wish for anything better than this; and if no other result has followed from fifty years of labour in Travancore, this would be an ample reward in itself.

At first we began by fraternizing with them entirely, then, after a few years, when they found out what scriptural Christianity really involved, and how very far apart they were from us, they drew off, and would have nothing more to say to us, nor allow us to preach in their churches. For some twenty-five or thirty years, accordingly, the only influence brought to bear upon the Syrian Church has been entirely from without: several Syrian congregations joined us in different parts of the country; indeed, all who wished to offer to God a spiritual and scriptural worship were obliged to come over to our Church, for they could get no instruction or help in their own.

For the last ten years, however, there has been a movement going on within the Syrian Church itself, and there are now no more accessions from them, nor could we desire it, so long as there is perfect freedom given to priest or layman to adopt a scriptural faith and a purer worship. Much of this reform is doubtless owing to the countenance and encouragement it received from the present Metran or Bishop, who rejoices in the high-sounding title of Mar Athanasius. We were his guests for [514/515] one night, on our way down from Mavelicurra to Quilon, at a place called Kayen Kulum, where we took up our quarters in the premises attached to the Syrian Church.

It was an interesting evening, and one that I shall not soon forget. One seemed transplanted back at once to the early days of Christianity as one gazed on the venerable old man with long iron-grey beard, clothed in a purple silk robe which reached nearly down to his feet, but in all other respects living in the most simple and primitive fashion; indeed, so scanty seemed his commissariat that we congratulated ourselves on having brought supplies with us, and being able, accordingly, to entertain him as a guest at table while we shared his quarters.

Fortunately for me he knew English, and could speak it with tolerable ease, having been educated, in fact, in our own institution in Madras, when presided over many years ago by Mr. Gray. We had a great deal of conversation together in reference to the Syrian Church, and he seemed really desirous of help and sympathy, and anxious to do all he could to raise the spiritual tone of his people. His position is a somewhat difficult and precarious one, for there is a rival Metran in the field, who also claims to derive his episcopal commission and authority from the Jacobite Church in Mesopotamia, with which the Syrian Church of Malabar has always been connected. Mar Athanasius has, however, been recognised as the rightful Metran by the Travancore Government, and he has certainly justified thus far the hopes then entertained of him that he would rule his people faithfully and promote among them a real reform.

We arrived just at dusk, and were welcomed on entering the churchyard or "close" by some seven or eight catanars, who greeted M. as an old friend. Among these was a young man, a nephew of the Bishop's, who, a few days before, had performed his first mass--as great an event, apparently, in the Syrian Church, as preaching the first sermon in ours; or greater still in one way, as it was followed by the feasting of no less than 5,000 persons at the Metran's expense, all of whom had come in to witness the ceremony.

After going up-stairs to the hay-loft sort of place over the gateway, which formed the episcopal residence, where we shook hands with the Metran and exchanged a few complimentary greetings, the young catanar spoken of above asked us if we would join them at their evening service. This we did, and found that he had summoned together a considerable congregation in the hope of hearing M. preach afterwards.

The service consisted partly of extemporised portions of the Syriac Liturgy, translated into Malagalim, which the officiating catanar repeated sentence by sentence, and which was afterwards taken up by the people; partly of prayers from the Liturgy itself. When it was over, the young catanar exchanged places with M., who read a portion of Scripture and [515/516] expounded it, evidently to the great satisfaction of his audience, for they were most attentive, the other six or seven catanars also standing by. There are only a few catanars as yet who venture to preach even from book, so that the people get very little teaching, and this makes them welcome all the more the occasional visit of a Missionary.

Another very interesting scene, which I also greatly enjoyed, was a visit paid one day to a Syrian house, where the owner, a well-to-do farmer, with a most pleasing countenance, received us most warmly, placed beds and mats at our disposal to recline on, and feasted us most sumptuously with all manner of curries, which he insisted on providing, though we had brought our own food with us. The room in which he entertained us was like a good-sized English summer-house, raised about three feet above the ground, with a floor nicely boarded and matted, and a roof thatched with cocoa-nut leaves. My seat was a bed, with one of the nice stained grass mats spread on it. At the edge of the platform M. sat on a low stool, and read a Malagalim tract about the Russian nobleman and the wolves to a group of some forty men and boys, who were seated outside on the ground, under the shade of the cocoa-nut trees, in the midst of a grove of which the house stood. Our host, who was a venerable patriarch, sat close to him, as he was rather deaf, drinking in every word, and nodding audible assents and occasional comments as he read.

On our way here we halted for an hour at another village, where there is also a congregation and a church. The people were all waiting for us, and some cannon, consisting of iron pipes, each four or five inches long, closed at one end, announced our approach. The little church has lately been renovated and almost wholly rebuilt by the congregation, and a nice porch added, and some fifty or sixty were present to meet us, and received a few words of instruction. Some plantains, a basin of milk, and another of coffee, had been provided for us, of which we were bound to partake, though we knew another repast awaited us at our next halting-place.

And so it is wherever we go. Every Syrian house and church is open to us; the people are all delighted to see us, and hear the Bible read and expounded.

On the whole, I must say that the Syrians are a most kind, hospitable people, and I felt greatly drawn to them. There is somewhat the same kind of hospitality to be met with from the monks connected with the Greek Church in Palestine, but, on the whole, I rather prefer the Syrians of Malabar. Nothing would be more interesting than spending three weeks or a month in a tour though all their churches, which number, I believe, some fifty within the immediate neighbourhood of our Mission Station at Mavelicurra.

Project Canterbury