First American Bishop of Honolulu, 1902-20

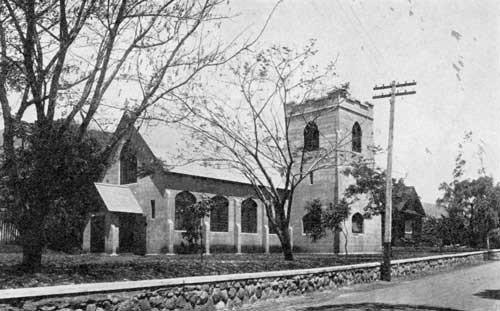

Rector, St. Peter's Church, Honolulu, 1895-1927

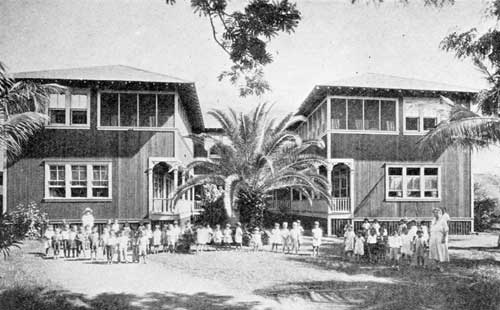

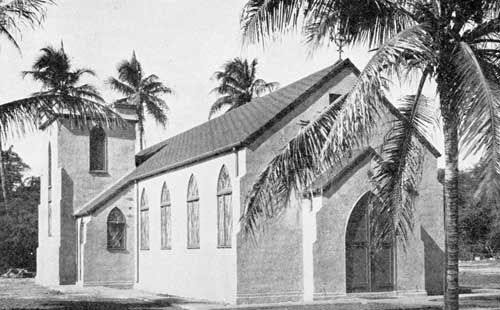

Kaimuki, Honolulu

Kaimuki, Honolulu

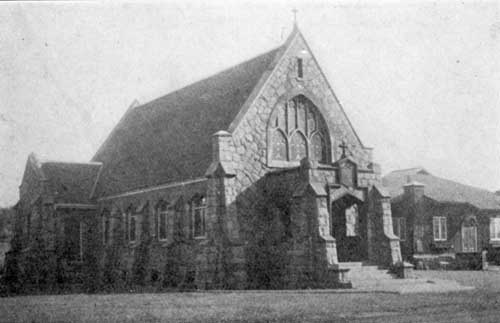

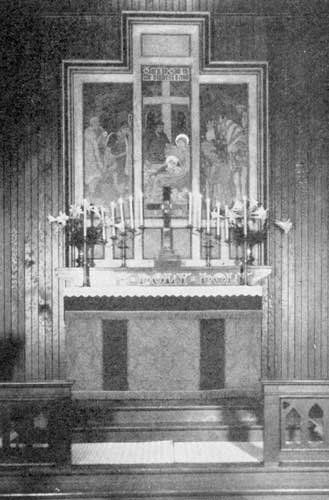

erected from stone found on the site

Consecrated February 20, 1927

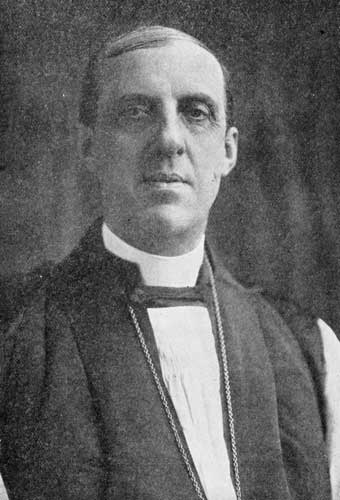

Second American Bishop of Honolulu, 1921-

On April 16, 1902, there flashed across the Pacific a message for the House of Bishops, then meeting, which read: "Transfer made. Good feeling prevails. Cathedral unified. Seldom better property or promise to start Missionary District. Movement to provide house for new Bishop. Young Bishop would rally young lay helpers. Disastrous to delay election." [Nichols, Days of My Age, p. 250.]

In response to this urgent appeal, there was elected the next day, as the first American Bishop of the Hawaiian Islands, the Rev. Henry Bond Restarick, then rector of St. Paul's Church, San Diego, California. This event, as intimated by the cablegram, was not the beginning of the Church in Hawaii. Something had gone before, and in order to understand the place of the American Church and its development during the past quarter century, a little of these antecedents must be known.

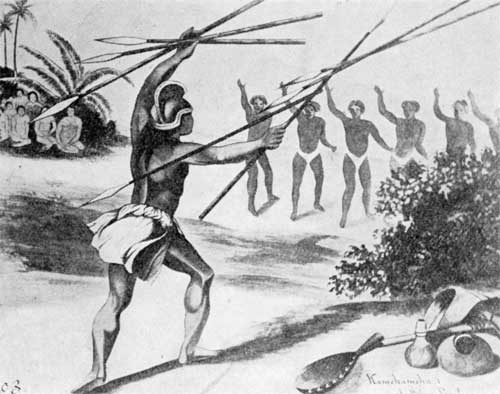

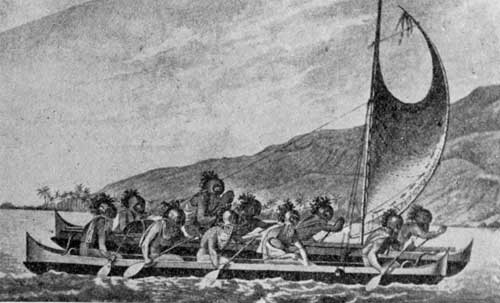

In 1555, the Spanish navigator Gaetano first sighted the Hawaiian Islands; but his discovery was kept secret, and it was not until 1778 that Captain James Cook, an English Churchman, in search of the evasive "Northwest Passage" from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic, rediscovered the Islands. Captain Cook set sail, in 1776, on his third voyage under instructions "to go first to the Society Islands and to sail thence to the coast of America at about 45 degrees north latitude from which point he was to skirt the coast northward, in search of the supposed strait." [Kuykendall and Gregory, History of Hawaii, p. 54.] Carefully following these directions, he came at daybreak on the morning of January 18, 1778, to the island [3/4] Kauai. The voyagers remained in this vicinity for some time, filling their water barrels and trading with the natives. Cook, in honor of his friend and patron the Earl of Sandwich, named the entire group, the Sandwich Islands. This name was never accepted by the natives who called themselves "Ka poe Hawaii"--the Hawaiian people--and their name for the Islands has prevailed. When Cook sailed away to the northwest he had not yet seen the three largest islands, and it was not until the following November, when he returned to winter in the Islands, that he first sighted Maui. During this visit the first recorded Christian service was held on Thursday, January 28, 1779, at Napoopoo, Hawaii. The occasion was the death of one of Cook's seamen, William Whatman: and the Christian Burial Service was read over his body before a great crowd of reverent and attentive Hawaiians. Less than a month later, on February 22, the second recorded service, again the Burial Office, was said; this time, over the body of the great explorer himself; killed by the natives as the result of an unfortunate encounter.

Cook's discovery opened a trade between the West and the Islands which led to frequent visits by British and American ships. In time, the Hawaiian Islands became a stepping stone between the Orient and the Occident. The Islands were as a door opening the East to the West, and the West to the East. Here, also, the later shipping lanes of the Pacific crossed--from San Francisco, 2089 miles to the northeast; from Panama, 4640 miles to the southeast; from New Zealand, 3800 miles south; to Hong Kong, 4950 miles west, and Yokohama, 3440 miles to the northwest.

Prominent among those who followed Cook was the English Churchman, Captain George Vancouver, who, between 1791 and 1795, spent three winters in the Islands and made many contributions to the welfare [4/7] of the islanders. He not only introduced many new products such as oranges and grape vines, cattle, sheep, and goats, but he also exerted great influence over the petty chiefs, whose warlike proclivities had kept the naturally peaceful islanders in a constant state of turmoil until just prior to Vancouver's arrival when the powerful Kamehameha I had won supremacy and established a line of capable rulers. To Kamehameha, Vancouver gave much sound advice, especially commending to him the services of two young Englishmen whose character was in marked contrast to that of other white men whom chance had deposited in the Islands. These two--John Young and Isaac Davis--were the sole survivors of the massacred crew of the trading schooner Fair American, who had belied the name of their vessel in their treatment of the natives when putting in for supplies in 1790. It is noteworthy that both of these young men were Churchmen, and that Davis had his Prayer Book with him--a copy still preserved among the treasures of the Church in Honolulu. It was largely through their influence with the reigning family that the power of taboo which had long been an element of cruelty in the native religion, was finally broken and the way paved for Christianity. Davis married into the ruling family and was the grandfather of Queen Emma, one of the most enlightened rulers of Hawaii.

The impression made by Vancouver was profound. Not only did his influence with Kamehameha lead the latter to consider the possibility of England's protective and developing hand in the future of the Islands, but he was also led to welcome Vancouver's promise that upon his approaching return to England he would use his influence to have Christian teachers sent to the Islands. Vancouver made an effort to fulfill this promise; but on his return he found England occupied with European troubles, and he himself died soon after.

[8] Meantime the Islands were not left entirely without the ministry of the Church, for Vancouver had discovered at Kealakekua an English chaplain, one John Howell, whom he could commend to Kamehameha along with Davis and Young. Howell's stay in the Islands proved brief, and little is known of him, but before he left in 1795, he is said to have acquired the language sufficiently to enable him to converse with the King regarding Christianity, and to have produced a further and lasting impression notwithstanding his refusal to subject himself or the God whom he preached to Kamehameha's naive proposal of a cliff-leaping test.

Other English chaplains visited the Islands from time to time and it was one of these who, early in the XIXth Century, celebrated the first Christian marriage according to the form of the Episcopal Church between James Young, the second son of John Young, and a daughter of Isaac Davis. These two pioneers of the Gospel remained high in the councils of the King and to them, with other English settlers, is to be ascribed the cessation of human sacrifices, the destruction of idolatry, the debasing taboos affecting the position of women, and the increasing acceptance of the belief that "the white man's god is the only God." To the last, Kamehameha resisted the inevitable, saying that he was too old to cast off his traditional gods who, he believed, had prospered him; but when he died in 1819 his favorite wife, Kaahumanu, publicly called upon the new King to break the system of taboo and all that went with it by admitting women to social and religious rites. This was done, and with the passing of taboo went the whole structure of idolatrous practice, though certain features persisted in secret for a long time.

In other ways, too, the English residents of Hawaii rendered real service to the natives. Crafts and trades were taught which the Hawaiians soon exercised with [8/11] the skill of Europeans. As early as 1810, it was reported that there was a theatre in Honolulu. Stone houses were also being erected there and at Kawaihae. Trading ships brought furniture, porcelain, silk, and many other articles in exchange for the native sandalwood. Everywhere, by 1820, the Hawaiians had made rapid progress toward civilization.

When, in that year, there appeared off Kailua a company of American missionaries the chiefs were doubtful whether they should be allowed to land. They remembered the promise of Vancouver to send men who would teach them about God. This promise was as yet unfulfilled. Accordingly, a council of chiefs was called and John Young was asked for his advice. He was known to have been trusted by Vancouver and they believed that he would tell them what Vancouver would wish to be done. Young told them: "These missionaries are the same as missionaries from England; they worship the same God and teach the same religion."

Thus the weight of Vancouver's promise was turned by the Anglican Churchman, Young, in favor of receiving the Americans, and they were granted permission to reside on the Islands for one year. In the meantime, Young was urged to write to England to inquire whether there was any objection on the part of the authorities to the American missionaries living and teaching on the Islands. The reply was favorable and the American mission was allowed to establish itself.

Vancouver's promise was not forgotten, however, and when, in November, 1823, Liholiho (Kamehameha II) sailed for England one of his purposes was to remind George IV of the English promise. Unfortunately, he contracted measles and died in England before he had even seen King George. His body was taken back to the Islands in a British warship and [11/12] at the interment the ship's Anglican chaplain read the Burial Office.

It would appear as if the Church of England regarded her chief duty in the Hawaiian Islands as consisting in the use of the Prayer Book at funerals. Promises die hard in primitive minds, and, on this occasion, the ship's commander was asked by the chiefs in council whether the King of England had now any objections to the continuance of the American missionaries. The reply was a somewhat indifferent negative, and thenceforth American influence steadily increased and spread.

Interesting as the succeeding years were in the development of foreign interests in the Islands, we must turn our attention to the spread of Christianity there, in many respects a far more fascinating tale than any other phase of Hawaiian development.

Those first American missionaries who landed in Hawaii were sent out by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions which was then supported by Congregationalists and Presbyterians. The first news which they heard on landing was that the taboo was broken and idolatry abolished. This was considered a direct answer to their prayers that a way might be opened for the Gospel.

"At first they had to suffer privations and discomforts. They had to live in grass houses and to eat food with which they were not familiar. Whatever some chiefs and white men had in the way of stone houses and household furniture, these Americans and the reenforcements which followed did not have for some time. They missed congenial society and found, as they must have expected, that the natives had few moral ideas such as prevailed in New England. Conditions to them seemed appalling, but they went to work with courage and ability.

[13] "They had a strange language to learn and reduce to writing, but they found eager and apt pupils among the chiefs when they began to teach. Nowhere in any field have missionaries received more kindliness and helpfulness than did these in Hawaii. There were causes for joy and for sorrow, for encouragement and disappointment, but they went on with their task." [Restarick, Hawaii From the Viewpoint of a Bishop, 1778-1920, p. 49.]

"The rules and regulations set by the missionaries were stern and strict and constituted burdens too great for the free and easy Hawaiians. It was the aim of these teachers to transform an Hawaiian village into the likeness of a New England small town. It was, of course, an impossible task and no teaching and example and no laws, however rigorous, could accomplish it." [Ibid, p. 50.]

For seven years; the American Board missionaries labored alone. Then, early in July 1827, there arrived at Honolulu the French ship La Comete with a band of Roman Catholic missionaries. Contrary to Hawaiian law which forbade the entrance of foreigners into the Islands without the permission of the King, the zealous missionaries landed and rented three grass huts. They were at once ordered to leave, but the ship on which they had come had sailed away without them and, there being no other means of departure at hand, nothing could be done but allow them to remain. They were also permitted to erect a chapel for their own use. When, early the next year, this was finished, many curious Hawaiians were attracted to it. For the most part the natives were shocked by what they saw. The Roman Catholic worship seemed almost identical with their own former idolatrous practices which, since 1819, had been prohibited. These matters were brought to the attention of Kamehameha III who [13/14] promptly issued a proclamation forbidding natives to attend the Roman services. Nevertheless, some natives continued to go to the Roman chapel, and when imprisonment, hard labor, and various other punishments failed to diminish their ardor, the King saw no other way to protect his people than to expel the priests. Accordingly, in April 1831, the Roman missionaries were summoned before the chiefs and told to leave the Islands within three months. The priests made no move to go. It finally became necessary for the King to provide a ship in which to deport them. This was done in December 1831, only one lay brother being left in the Islands to care for their interest and to keep his superiors informed of the situation. In 1835, another lay brother was sent to Honolulu, and the next year Father Walsh, a British subject, came. He was ordered to leave, but the timely arrival of French and British warships interfered, and through the intercession of the French commander the chiefs gave him permission to remain and to teach foreigners but not natives. The English commander, Lord Edward Russell, then negotiated a treaty whereby British subjects, with the consent of the King, were granted permission to trade, to reside, and to build houses and warehouses in Hawaii. An unsuccessful effort was also made to secure permission for Father Walsh to teach and baptize natives. Nevertheless, during the next few years, he did baptize a few Hawaiians.

In the meantime, the exiled French missionaries eagerly awaited an opportunity to return. This seemed possible in 1837, but after much controversy they were again forced to leave. The publicity given this event led the Roman Bishop of Eastern Oceania to send two other priests to seek residence in Hawaii. This attempt was no more successful, and shortly after their departure Kamehameha III issued a proclamation absolutely forbidding the teaching or practice of Roman Catholic doctrines and prohibiting teachers of that [14/17] communion from entering the Hawaiian Islands. "A vigorous effort was made to enforce this law and the persecution of native Catholics was renewed. As a result a large company of them left Honolulu and went to the District of Waianea, where the local chief was friendly. But they were not allowed to remain there permanently." [Kuykendall and Gregory, History of Hawaii. p. 149.]

Meantime, it began to be realized that such drastic prohibitory legislation involving the French missionaries might lead to complications with the French government; it was contrary, too, to the advice of those who had influence with the Hawaiians. As a result, there was issued in 1839 an Edict of Toleration ordering that punishment should no longer be inflicted on Roman Catholics. Thus official effort to keep Romanism out of the Islands came to an end and henceforth the work of the Roman Mission prospered without governmental hindrance.

In passing, it is only fair to note that is was the State and not the Church which was responsible for the ten-years ban on Roman Catholicism. From the very first, it was the religion of Vancouver and Davis, as expressed in the Prayer Book, which had so commended itself to the natives that it had virtually become the State religion. When the Roman priests came, not only did they disregard the law of the land in forcing an entry, but their ceremonies and worship seemed to the natives to resemble more closely what they had abandoned than what they had adopted. Therefore, this "second religion" was proscribed by law, and it was largely through the influence of the American missionaries and other foreigners that the Edict of Toleration was finally enacted.

In the meantime, there were those who, in the face of repeated neglect, still trusted the promise of Vancouver to procure an Anglican clergyman for the [17/18] Islands, and who recalled the ill-fated visit of Liholiho to England for the same purpose. This was evident when, in 1830, the Hawaiians turned to the Seamen's Friend Society of New York and urged that a chaplain be sent to Honolulu. Although the secretary of that Society was a Churchman, it appears that the first clergyman sent out in answer to this appeal was not. The Rev. John Diel went to Honolulu in 1833, the same year that Bethel Chapel was erected; but it was not until after his departure in 1840, that regular public services of the Anglican Church were held, and these by a layman. The Honolulu Polynesian for July 25, 1840, reported that: "Episcopal service was read with a sermon in the Chapel, by P. A. Brinsmade, Esq., who will continue the same until the pulpit is regularly supplied." Mr. Brinsmade who was the American Consul in Honolulu continued as lay-reader for some time.

In the autumn of the next year, a New York Church paper reported a request for a priest of the Church, in these words: "Seldom has a more interesting application come before the Committee than that an Episcopal clergyman be sent to be resident in Honolulu. The foreign residents, about forty families, desire the services of the Church. On the failure of the former chaplain, the service had been actually commenced by the American Consul. The pledge of one-half of the needful expense, a chapel and a parsonage, are sufficient evidence that the labors of a missionary of our Church would be appreciated in that group of Islands." This request was not granted, and the community in Honolulu were dependent upon such services as could be provided for them by another Seamen's chaplain who went out in 1842 and by such ship chaplains as visited the port.

Nevertheless, their earnestness seemed proof against every rebuff. The editor of The Polynesian in the issue for July 13, 1844, reported that "in conversing [18/19] with people who desired a Church other than the Bethel, they have unanimously expressed their opinion in favor of a selection from the Episcopal Church and this opinion is mainly from those not of that faith themselves, but consider her discipline and doctrine as best calculated to unite a community in which so great a diversity of opinions on religious subjects prevails."

This was not an isolated outburst of interest. The Polynesian constantly referred to the Church, and it was through its columns that R. C. Wyllie, a Scotchman who became Minister of Foreign Affairs, in 1845. announced to all residents belonging to the Episcopal Church, that a former resident would give $1000 toward the erection of a suitable church building, provided that the sum of $4000 were subscribed in Honolulu.

A few weeks later he issued, at the command of the King, a circular, "to ascertain the feelings of the foreign community in regard to the want of an Episcopal church or chapel and the willingness to subscribe to its support." Admiral Thomas offered to endeavor to secure a properly qualified clergyman, and those who were interested in the project were requested to indicate the amount they would subscribe annually for the support of the Church. Nothing came of this effort, due, no doubt to the general exodus from the Islands in 1848 following the discovery of gold in California.

In 1852, the desire for the Church was still alive. The Honolulu Argus reported about that time as follows: "We have much pleasure in noticing the growing interest manifested by the community in the performance of the beautiful service of the liturgy of the Episcopal Church at Mauna Kilika. We are glad to learn that it will be repeated next Sunday." This congregation was in charge of a Mr. Smeathman, in Deacon's Orders, and it was unfortunate that ill health [19/20] forced him to leave the Islands after only six months' residence. Although his retirement brought the services in Mauna Kilika to an end, the interest in the Church continued. This is evident from the records of regular services conducted by laymen in many of the homes of Church people.

Admirable as these efforts were in ministering to the foreign residents of Honolulu and in maintaining interest in the Church, no really effective or permanent work could be done without a resident Bishop. The first official step in this direction was a request for a clergyman addressed to Bishop Kip of California. The Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Hon. R. C. Wyllie, wrote several times to Bishop Kip on this subject, but the latter was unable to secure any encouragement in the matter from the Board of Missions. Consequently, while in England in the summer of 1860, he laid the project before the Bishops of Oxford and London. They regarded the proposal with favor, and due largely to their efforts, the Rev. Thomas Nettleship Staley, fellow of Queen's College, Oxford, and a tutor of St. Mark's College, Chelsea, was consecrated on December 15, 1861, as Bishop for Honolulu. Bishop Staley reached Honolulu on Saturday, October 11, 1862, and early the next morning celebrated the Holy Communion in a building which had been hastily transformed into a chapel. While this celebration was undoubtedly the first said by an Anglican Bishop in the Islands, it was not the first Eucharist celebrated in those parts. As early as 1816, a priest who was with the Russian navigator Kotzebue, officiated according to the rite of the Greek Orthodox Church. From that time, the Eucharist was celebrated at irregular intervals by chaplains of the Church of England who happened to be in the Islands.

The Mission inaugurated by Bishop Staley was almost immediately incorporated as the Hawaiian Reformed Catholic Church. It was intended to be a [20/21] joint English and American venture, but conditions in the United States, especially the Civil War and the days of reconstruction which followed, prevented the carrying out of this plan.

A continual source of encouragement to Bishop Staley was the steadfast devotion of Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma to the Mission. Confirmed on November 28, 1862, the sovereigns gave generously of their time and influence. Not infrequently they were sponsors in Baptism, and the King prepared an Hawaiian translation of the Book of Common Prayer. He also rendered invaluable service in assisting Bishop Staley in the preparation and delivery of his sermons in Hawaiian. The Queen also constantly devoted herself to her people,--tenderly caring for the sick, founding a free hospital, and bringing the children to Baptism. Apart from the loyalty and devotion of the Royal Family to the Anglican Mission, Bishop Staley and his co-workers were faced not only by almost insurmountable difficulties, but received very little active support from the residents of Hawaii, either native or foreign. Owing to the long continued apathy of the Church of England as well as of the Episcopal Church in America, the Congregationalists had had for years a practically free field. Since the opening of their Mission, conditions had become completely reversed. Then, they had been allowed on sufferance to enter a field opened by the Anglican Church and offering; unique opportunities to that Church; now, through their untiring zeal and a corresponding lack of interest on the part of the first-comers, their mission was dominant in the Islands and it was the Church of England which had to sue for tolerance.

Finally, in 1870. after seven years of effort Bishop Staley felt obliged to resign. Something of the temper of the times is evident in a contemporary news item which appeared in the Honolulu Advertiser: "Since the return of Bishop Staley several months [21/22] ago, several exciting meetings took place. Bishop Staley will return to England and resign. All the members of the staff will retire. Thus after seven years of trial the experiment of building up an expensive ecclesiastical establishment unsuited to the wants of the place and repugnant to the tastes of the people, has proved a failure and will be abandoned.

"The establishment here of the Reformed Catholic Church was one of the visionary schemes of the late R. C. Wyllie and never met with the cordial support of English or American Episcopalians for the main object appeared transparent from the first to be political rather than religious." [Quoted by Restarick, Hawaii From the Viewpoint of a Bishop, 1778-1920, p. 121.]

There was, however, no intention on the part of the authorities to abandon the Hawaiian venture. The Archbishop of Canterbury to whom had been intrusted the task of selecting a new Bishop sought to persuade Bishop Whipple of Minnesota to accept the Hawaiian Bishopric. Bishop Whipple was at that time seriously ill and his physician had advised him to seek a warm climate such as the Hawaiian offer made possible. He sought the advice of six of his brother Bishops, but their counsel was so diverse that the final decision rested with himself. Finally, he informed the Archbishop of Canterbury that after one of the hardest trials of his life he had decided to remain in Minnesota. Failing to secure an American Bishop, the English authorities then turned to a successful parish priest, the Rev. Alfred Willis, who accepted the call and was consecrated February 2, 1872, in Lambeth Chapel.

Bishop Willis arrived in Honolulu the following June accompanied by several new missionaries. He found the Church in Hawaii at a very low ebb. In the more than two years which had elapsed since the [22/23] resignation of Bishop Staley, there had been months without a celebration of the Holy Communion, and the Church had lost much of her former prestige.

Bishop Willis faced the difficulties of the situation as a man to whom a strong faith gave courage, strengthened by such tangible evidences as the promises of the King and Miss Priscilla Lydia Sellon to subscribe 200 pounds a year each, for five years.

Although Bishop Staley's episcopate was short and fraught with hardship, he had laid firm and broad foundations for the future growth of the Church. Upon these foundations Bishop Willis built and when after thirty years' labor political events made desirable a transfer of jurisdiction from the English to the American Church, the Anglican Church in Hawaii, as it was then called, was well established in half a dozen or more places on the three main islands--Oahu, Maui, and Hawaii.

Honolulu, on the Island of Oahu was, of course, the centre from which radiated the Church's life. Here, on land given by Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma, was the half-finished St. Andrew's Cathedral. Adjoining the Cathedral, on land given in 1885 by Queen Emma, was St. Peter's Church for Chinese. At Waialua, on the same island, the Church owned some school property, but in 1902, this was not being used.

On Maui, there were four centres--Lahaina, Wailuku, Keokea, and Kula. As early as 1863, a small piece of land had been secured in Lahaina for use as a cemetery, but it was not until 1874 that a site for a church was secured and Holy Innocents erected. About this time, also, the Crown Commissioners granted the Church a piece of land in Wailuku upon which was erected the Church of the Good Shepherd and a rectory. At Keokea, the Church owned a small cottage, while in Kula, a work among the Chinese had [23/24] been begun although, in 1902, there were as yet no buildings.

On the Island of Hawaii, the Church owned several acres of land at Kona where was located Christ Church with rectory and schoolroom. On the northerly point of the island, at Kohala was St. Augustine's Church. For the large Chinese population of this region St. Paul's Church and School were established in the Makapala district. At Honokaa and Paauilo, the Church had received gifts of land sufficient for the erection of churches and other necessary buildings.

Through these agencies the Church of England was ministering to Hawaiians, part-Hawaiians, Americans and other English-speaking peoples, and Chinese, and with its 2000 baptized members of varied races and nationalities, was beginning to be truly representative of the land in which it worked--the "Crossroads of the Pacific" where East and West truly met and mingled. To reach these people with the saving message of Christ was the task of the Church in the Islands.

In addition to the churches there were two well established schools--St. Andrew's Priory for girls and Iolani School for boys. From the very inception of the Anglican Mission in Hawaii there had been a marked interest in Christian education. During the first year of Bishop Staley's episcopate, Archdeacon and Mrs. Mason began, in Honolulu, St. Alban's College for boys and a girls' boarding school. The King, at a cost of $4000, erected buildings for the latter which, on the removal of the girls' school to Lahaina, Maui, were turned over to St. Alban's College.

The girls' school at Lahaina, named St. Cross, provided the opportunity for the establishment of an enduring educational work for girls by the Society of the Holy Trinity. This Order commonly called the Devonport Sisters after the location of the Mother House at Devonport, England, had been founded by [24/25] Miss Sellon, one of the early supporters of the Hawaiian Mission and was one of the first Religious Orders for women in the English Church. In 1867, two Sisters were sent out to take charge of St. Cross School and this venture proving successful, the Sisterhood presently opened a similar school--St. Andrew's Priory--for which a site on the Cathedral property in Honolulu was granted. In 1890, the Sisterhood in England found itself in such precarious financial straits that is was compelled to withdraw its support. It was thereupon proposed that the two Sisters in charge should return to England; but they were so devoted to their task that they begged to be allowed to remain in Honolulu, depending upon such support as they themselves could secure. Their plea was heeded and they continued in charge of the Priory until the transfer of jurisdiction to the American Church.

The buildings occupied by St. Alban's College stood on leased ground. When Bishop Willis went to the Islands, he thought it would be desirable to have the College on land which the Church owned. Accordingly the buildings which the King had erected for the original girls' school were moved to a site on Bates Street. Here the boarding and day departments were continued. The School had been originally intended for the Christian education of Hawaiians and part-whites; but very soon it was decided to admit Chinese boys as well. These came in increasing numbers, and by 1892 they were winning many of the school prizes. It is interesting to note that during, these years one of the students was Tai Chu, better known as Sun Yat Sen, the great Chinese nationalist reformer. Another of Bishop Willis' innovations was to change the name of the School, and shortly after his arrival, he re-named it Iolani College.

Such then was the physical equipment of the work when Bishop Willis retired. It included seven [25/26] churches, three school buildings, and three rectories; the total value amounting to $101,600. The endowment of the episcopate was $7000.

When, in 1898, and at their own request, annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by the United States became an accomplished fact, Bishop Willis was confronted with its possible effect upon the Church. Although it was against all precedent for the Church of England to maintain work in what was now American territory, the relation of the Church in Hawaii to Canterbury would remain unchanged until General Convention took action. It will be recalled that in consequence of the inability of the American Church to establish a Mission in Hawaii, the English Church, at the request of American Bishops undertook the work. A joint American-English Mission proving impractical, the See of Honolulu had been founded as an independent Diocese in communion with the Churches of England and America, and for thirty-six years the work had gone on. Nothing would be done to break this continuity and any action of General Convention would, of course, be in the direction of supporting and strengthening the work.

Many questions were involved. The Bishop of Honolulu received the Mission and jurisdiction from the Archbishop of Canterbury in whose hands, therefore, rested all question of transfer. Financial responsibility was of prime importance in this connection. Nothing could be done until this was satisfactorily arranged between the Churches in England and America. Although, the committee to which the matter was referred in America reported to the General Convention of 1898 that it was inexpedient to interfere at that time with the existing status, the S. P. G. which from the first had aided the mission in Honolulu, advised Bishop Willis that after June 30, 1900, its support would be withdrawn.

[27] As to the Prayer Book, Bishop Willis said that the English Book would be continued in use with such necessary changes as the situation demanded, but if any American Churchmen desired to erect a church and use the American Book he would be glad to meet their wishes.

In 1901, Bishop Willis attended General Convention where the question of the transfer of jurisdiction was definitely faced. The Committee on the Admission of New Dioceses to which the question had been referred by the House of Clerical and Lay Deputies reported that it was not competent to consider the question. The House of Bishops then dealt with the subject. It announced that an agreement had been reached with the authorities in England whereby the Diocese of Honolulu should be constituted a Missionary District 'of the American Church. After the settlement of a few minor questions, it was promptly agreed to set April 1, 1902, as the date for the formal transfer.

Bishop Willis promptly resigned as the Bishop of Honolulu and upon his return from San Francisco called a meeting of the Synod. Resolutions were adopted accepting the doctrine, discipline, and worship of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the U. S. A. and that the Trustees of the Anglican Church in Hawaii apply to the civil authorities for its approval of certain amendments to its Charter of Incorporation. "This was accomplished on January 15, 1902, and the corporation which was at first the Reformed Catholic Church, then the Anglican Church in Hawaii, became the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Hawaiian Islands. It was the same Church under different names. Corporate names could not change its being an integral part of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic [27/28] Church, belief in which is professed in the Nicene Creed." [Restarick, Hawaii From the Viewpoint of a Bishop, 1778-1920, p. 182.]

From the signing of the revised charter on January 15, a modus vivendi became necessary until de facto as well as de jure the Episcopal Church could, on April 1, assume jurisdiction. [Cf. ibid, pp. 184 ff. for details.]

The Presiding Bishop designated Bishop Nichols of California as his representative to receive the Hawaiian Mission from the English Church. Bishop Nichols, accordingly, proceeded to Honolulu, in March, 1902, and on the appointed day received authority and jurisdiction as Bishop-in-charge of the Missionary District of Honolulu. He spent two months there attending to the many details incident to the transfer and in preparation for the coming of the resident Bishop who, as already stated, had been elected in response to his cable informing the House of Bishops of the transfer.

Bishop Nichols found in Honolulu a schism in the Cathedral congregation. This was generally recognized; each congregation--the "Cathedral" and' the so-called "Second"--had its own clergy and went its way in utter disregard of the other. Very wisely, Bishop Nichols took no notice of the divided congregation. He appointed the clergy of both congregations as Canons of the Cathedral to officiate in torn under the Bishop as Dean. He also gave St. Clement's parish provisional organization pending the selection of a Constitution and Canons by the permanent Bishop. Another of Bishop Nichols' acts was the organization of a branch of the Seamen's Church Institute.

The first American Bishop of the Hawaiian Islands, the Rt. Rev. Henry Bond Restarick, was consecrated on July 2, 1902, in St. Paul's Church, San Diego, [28/29] where for a full score of years he had, in the words of Bishop Nichols, shown himself "the parish builder, the thoughtful and instructive preacher and writer, the moulder and leader of men, the sound and sympathetic counsellor, the trusted representative in Diocesan and General Conventions, and the man of wide outlook upon the general affairs of the Church." The Bishop sailed on August 1, accompanied by four of his parishioners who had volunteered to labor with him in his new field, which included in addition to the Hawaiian Islands, the American islands of the Samoan group. [No work has been done on these Islands by the American Church, although the English Bishop of Polynesia has twice visited the port of Pago Pago for the Bishop of Honolulu.] A week later the party arrived in Honolulu, and on August 10, in St. Andrew's Cathedral, Bishop Restarick celebrated the Holy Communion, his first service in his new jurisdiction.

A large and difficult task confronted the new Bishop. Although, as we have seen, Bishop Nichols had taken no notice of the factions existing in Honolulu, trouble still existed between the partisans. Following the example and advice of Bishop Nichols, Bishop Restarick appointed himself Dean of the Cathedral, thereby avoiding any partiality to either party and taking the first step toward creating a united and harmonious District.

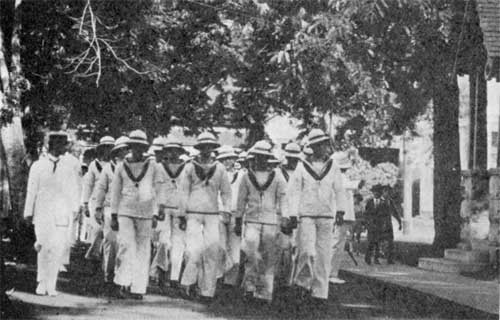

It was necessary to organize the District as soon as possible under the Constitution and Canons selected by the Bishop. Accordingly on November 1920, 1902, the first convocation met. Interest ran high as to what the spirit of the meeting would be. Many feared that it would be marred by some discordant note. Happily, it went off without a single disturbing episode although the two factions were about equally represented. There was no attempt to displace men who had held office under the former administration, and harmony and good will prevailed. This is [29/30] especially noteworthy as the task of bringing the District in line with the organization of the American Church was not an easy one, since only one man present besides the Bishop was familiar with the spirit and operation of American Church Government. Following the example of many other Dioceses, the day after Convocation was given over to the first diocesan meeting of the Woman's Auxiliary at which steps were taken to organize a District branch. Another clay was devoted to a discussion of Christian education--a plan which proved continuously valuable for many years.

Other difficulties confronted Bishop Restarick. His staff numbered but six priests and two deacons, while three centres of work--Paauilo, Kona, and Kohala--were vacant. These and many new places calling for the Church were in need of men if the Church were to go steadily forward increasing in numbers and influence with the passing years. The difficulty of this situation was aggravated by the unusually small stipend paid the clergy. Some relief came to the Bishop, in 1905, when an Island layman offered to give him $2500 a year to augment clerical salaries.

The economic life of the Islands had always been largely dependent upon the price of sugar. During the early years of Bishop Restarick's episcopate, the price of sugar was low, many plantations were not paying dividends, and money was scarce. There were also other elements which contributed to the business depression of the time and added to the difficulties of securing in the Islands, themselves, the necessary funds for the advance of the Church. Among these should be noted the unsettled labor conditions resulting from the transfer of political jurisdiction, the collapse of the boom which preceded the actual transfer, and the change in the customs administration. Prior to the annexation, the receipts from the customs had remained in the Islands, but with the coming of the [30/33] Americans all such revenues were sent to the United States. Thus the economic situation was a difficult one, but this was not all. Relations with other Christian bodies, relations between the many races meeting and mingling in the Islands, the rapid influx of Japanese already the largest racial group in the Islands--all these factors in the situation presented difficult problems which required tact, discretion, and statesmanship in the handling. Bishop Restarick's office was evidently no sinecure. Let us turn, then, to the story of the Church in the Hawaiian Islands as it developed during its first quarter-century under American supervision; and since all aspects of the varied work find expression in Honolulu, that centre may well demand our first attention.

THE CHURCH IN HONOLULU The centre of Church life in Honolulu is St. Andrew's Cathedral. The half-finished building to which Bishop Restarick went early on the morning of August 10, 1902, for his first Hawaiian celebration of the Holy Communion was the fruition of one of the earlier plans of Bishop Staley. When Kamehameha IV died on St. Andrew's Day, 1863, it seemed fitting that the proposed Cathedral should be erected in his memory and dedicated to St. Andrew. This plan met with instant approval and enthusiastic support. Queen Emma, who was heartily in favor of the plan, journeyed to England in its behalf and secured some six thousand pounds.

On March 5, 1867, Kamehameha V laid the cornerstone. Unfortunately, Bishop Staley's return to England brought the work to an end with only the choir and tower foundations completed. Nothing further was done for about a decade. The stone which had been sent out from England was allowed to remain crated on the ground. The congregation seemed satisfied to continue worshipping in the small frame Pro-Cathedral which had served them since 1866.

[34] In 1882, construction on the walls was begun, and four years later, on Christmas Day, the choir was finished and used for worship. The next Synod meeting was opened in the Cathedral with an address by the Bishop in which he hailed the finished work as marking a new era in the history of the Church in Hawaii. It was a witness to the abiding character of the Church and to the fact that the Anglican Church was permanently established there.

In 1901, Bishop Willis gave the total cost of the Cathedral as $85,000, all but $1,700 of which had been paid. This sum, Bishop Willis advanced personally, and on March 9, 1902, consecrated the building.

When Bishop Restarick arrived in Honolulu, the Cathedral was in sad need of repairs. He at once devoted some of his discretionary funds to this purpose, and when people saw that there was to be progress a general interest in improvements resulted. The Woman's Guild set about replacing the unsatisfactory oil lamps with electric lights, and the old worm-eaten and unsafe pews with new substantial ones.

Bishop Restarick was also interested in extending the nave of the Cathedral by the addition of two bays. He was unwilling, however, that this work should be undertaken until the $1,700 owing to Bishop Willis was paid. In 1903, the Easter Offering was devoted to this purpose, and it is noteworthy that this offering, together with but a few additional gifts, was entirely adequate for the purpose. The way was now open to plan the enlargement.

To this end, the Easter Offerings of the three subsequent years were devoted. The people gave generously, realizing that while aid for the missionary work in the Islands might properly be solicited from friends on the mainland, money for the Cathedral must be given by the people in Hawaii. By 1906, [34/35] sufficient funds were in hand to begin work, and on November 23 the first stone was laid. A year and a half later (May, 1908) the enlarged building was finished. In his annual address to the first Convocation which met in the enlarged Cathedral, the Bishop reviewed the history of the building, referred to the opportunities for memorials, and said that the extent lion had cost $27,000, of which $2,700 had yet to be raised. As he concluded his address, a slip was handed him which he read to the congregation: "Some of your friends have subscribed $2,700 and there is no longer any debt." Great was the rejoicing and the people arose and sang the doxology. The addition to the Cathedral was consecrated on July 19, 1908. But the congregation was not yet satisfied. Many desired the completion of the West End, by the addition of two bays, a baptistry, and a morning chapel. Plans for these were drawn and presented to the Cathedral. In 1926, this was still an unrealized ambition.

While St. Andrew's Cathedral was the spiritual home of mainly the English-speaking white residents of Honolulu, fully a third of the communicants in the city were Hawaiians, many of whom worshipped at the Cathedral, besides a scattering of other races.

When Bishop Restarick arrived, the relations existing between the various racial groups in the parish were not especially cordial. At the request of the Hawaiians, therefore, the Bishop organized them in a separate congregation and assigned them hours for worship. On its part, the native congregation assumed part of the expense of maintaining the Cathedral. This proved a very wise measure. The communicants grew from 50 in 1902 to 267 in 1919, while the contributions increased from $217 to $1,640 during those same years.

In the beginning, the Hawaiian services were conducted in that language; but as a new generation [35/36] grew up entirely unfamiliar with their native tongue, English was more and more introduced into the services. Other problems also arose, two of which in particular affected all Hawaiian work.

The feeling was almost universal among the Hawaiians that the American annexation of the Islands had been brought about largely by the missionaries. This sentiment was especially noticed by the Congregationalists who experienced a large falling off in their membership. The feeling was also prevalent that the Cathedral Hawaiian congregation was the centre of anti-American feeling. Indeed, the editor of one of the most vigorous anti-American newspapers was a member of the Hawaiian congregation. This state of affairs naturally caused considerable feeling and might have led to serious consequences and done irreparable harm to the Church's Hawaiian work had not Bishop Restarick wisely refused to be drawn into the controversy.

The second problem--that of securing regular church attendance, more vitally affected the Church, but it must be remembered that it was not peculiar to our Church but was shared by the Roman and Protestant bodies as well. Undoubtedly the organization of the Hawaiian congregation which gave its members a real sense of corporate unity did much to combat the tendency of irregularity upon church worship. How else can the increase in communicants during 17 years from 50 to 267 be accounted for? Without this organization it is quite certain that the Hawaiian group worshipping at the Cathedral would have been dissipated until finally not one would have remained. Happily, the congregation was organized and prospered under Bishop Restarick's wise direction.

Undoubtedly another factor in keeping the Hawaiians together was the fine example of Queen Liliuokalani. Her regular attendance at worship did much to hold the people together. It was her [36/39] influence which led Prince Kalanianaole and his wife to Confirmation. When a Woman's Guild was organized among the Hawaiians, the Queen became its president, which office she retained for several years.

The important part played by women in the Hawaiian congregation should not be overlooked. Three in particular were especially indefatigable and devoted in their service to the Church. Of these. Bishop Restarick wrote: "I have had with me many fine women workers, but none for whom I had greater respect and regard than for these three of Hawaiian blood . . . When Mrs. Kawaihoa was upon the platform at the annual meeting of the Woman's Auxiliary, reading a report, it was a striking lesson of what the religion of Jesus Christ has done for women.

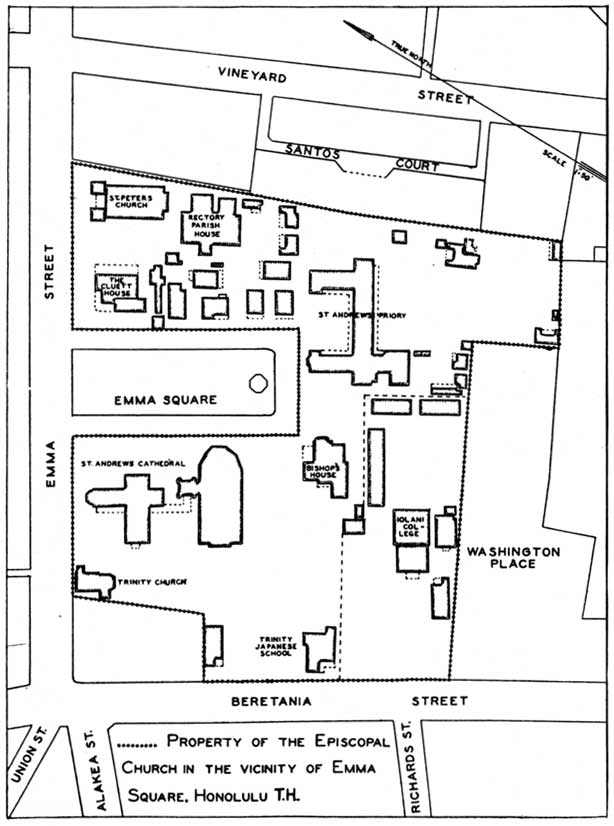

Unfinished as the material fabric of the Cathedral was, it was nevertheless the ideal Bishop's churcha centre of strength and spiritual power, a focus of energy, a radiating point of help and blessing to mind and soul and body, the very hearthstone of the Church's family. About it, on every side, there gradually developed a great church plant. Today, seven acres of land about Emma Square are occupied by church buildings. This centre developed slowly.

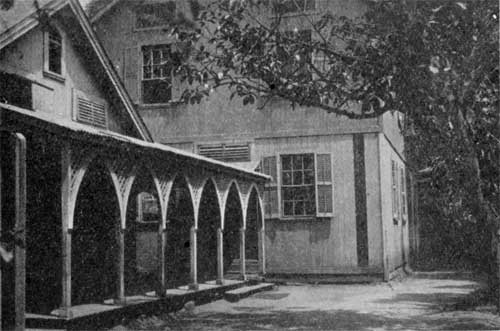

In 1902, the old wooden Pro-Cathedral, in wretched condition, was used by the Sunday School and during the week by Iolani School. A movement was started to secure property adjoining the Cathedral on which to erect a building for parochial purposes. This land was the property of two different owners and before the Church authorities could enter into negotiations for its purchase, it was found that the entire corner had been bought by an unknown person. Some time later, the Bishop was informed that the Davies family were the purchasers and that they had in mind a Parish House as a memorial to Theophilus Harris Davies.

[40] The gift having been formally offered and accepted, the corner-stone was laid on May 9, 1907, by Queen Liliuokalani. Two years later, on Whitsunday, 1909, the Davies Memorial Building was dedicated. The building, completed, furnished, and connected with the Cathedral by an attractive cloister, gave a greatly needed addition to the Cathedral plant and the additional grounds were a fine improvement to the Cathedral Close.

When the Davies Memorial Building was erected, a part of the agreement with the donors was that the Pro-Cathedral was to be torn down. Accordingly, in the summer of 1909, the building around which had centred so many Church associations for nearly half a century was razed.

Another requirement of a well-equipped Cathedral plant was a suitable Bishop's residence. For some years, Bishop Restarick lived in various rented houses. None was entirely satisfactory and all were a heavy drain on his salary. A residence close to the Cathedral was desirable. Accordingly, in 1910, it was decided to build a suitable house on the old Priory site and, in November, 1911, Bishop Restarick was able to move into the new house.

One of the earliest of foreign peoples to be attracted to the Hawaiian Islands were the Chinese. They were interested in the sandalwood found there and soon a large trade developed in this product between the Islands and Canton. Vancouver had recorded meeting Chinese in Hawaii, but it was not until after 1876 that they came in any large numbers. Then the development of large sugar plantations, encouraged by reciprocal treaties with the United States, led to a demand for a large supply of laborers. When an attempt to introduce German immigrants proved unsuccessful, it was decided to bring in Chinese farmers. This experiment sponsored by the Government was successful, and within a few years large [40/43] numbers of Chinese peasant families were resident in the Islands. For the most part the plantation owners felt a certain responsibility for these workers and encouraged missionary activity among them.

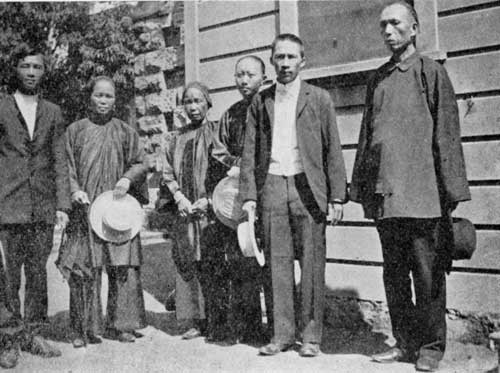

Bishop Willis early took a great interest in the Chinese. Quite naturally, the first work among them was begun in Kohala, the centre of a sugar plantation region; but in 1886, a group of Chinese had come up to the city from Kohala, and that they might not lose touch with the Church, Bishop Willis secured, to minister to them, the Rev. H. H. Gowen, an expert orientalist, now Professor of Oriental Languages and Literature in the University of the State of Washington. The first Chinese service was held on September 19, 1886, and they were continued occasionally until the following Palm Sunday, when the Chinese were organized into a congregation and regular services were provided in the Pro-Cathedral. A church of their own was a necessity and on March 1, 1891, the Church of St. Peter the Apostle was consecrated. Ten years later, the congregation included 190 communicants; men were being prepared for the ministry, and the influence of the parish was extending in various parts of the city. By 1911, the original church was outgrown and plans were made for a new and larger building. A lot adjoining the Gillett House near the Cathedral was secured and, in 1914, the corner-stone was laid. When completed, the entire cost of land, building, and furniture, amounting to nearly $36,000, had been fully paid by the Chinese themselves. Accordingly, the first service held in the new St. Peter's on the Sunday next before Advent, 1914 was its consecration. On the same day, 24 children were baptized and 30 were presented to the Bishop for Confirmation. With the consecration of the new church, the work progressed steadily; and in 1920, plans were made for a parish house. This Chinese mission in Honolulu had always exerted an influence extending [43/44] far beyond its borders. In common with other Orientals, the Chinese have a peculiar veneration for their own land; they rarely seek citizenship elsewhere, and however far they may have wandered, it is almost always with the determination of returning home eventually. Honolulu affords no exception to this rule; consequently there has been a constant flow of Chinese Christians from St. Peter's parish to their own country, where many of them have become influential members of the Chinese Church and missionaries to their fellow-countrymen at home.

In 1902, the Church had no work among the Japanese--the largest single racial group in the Islands and, at that time, numbering about 70,000. Bishop Willis had recognized the necessity of a Japanese mission but had never been able to undertake it. Bishop Restarick was of like mind and eagerly sought an opportunity to minister to the Japanese. In 1906, there was brought to Bishop Restarick's attention a young Japanese, Philip T. Fukao, a graduate of a C. M. S. College in Japan but ordained in the Presbyterian ministry. In explanation, he said that he had never been told that there was any real difference, other than the name, but that now he wished to return to the Church in which he had been confirmed. Inquiry revealed that he was of sterling character, and in April, 1906, he was licensed as lay reader and catechist.

Mr. Fukao immediately opened a night school for young men of his race in a cottage at the rear of St. Peter's Church. In compliment to the church in Osaka in which he had been baptized, the new mission was named Holy Trinity. The work grew steadily and in a few years a building which came to be known as Trinity Mission House was rented. This house provided on the upper floor quarters for the workers, and on the lower floor facilities for the day and night schools.

[45] The Japanese congregation which gathered about these various activities worshipped, at first, in a room in Iolani School; but when the new St. Peter's Church was built, the old building was given to the Japanese, and at the same time a building fund was begun. The congregation continued in charge of Mr. Fukao, who had been ordained deacon in 1911 and advanced to the priesthood in 1914.

The work has presented many difficulties. Constant removals reduced the size of the congregation, which losses had to be made up by new converts. In this, Mr. Fukao was very successful, for in the course of a dozen or more years he baptized over 200 and presented over 100 for Confirmation. Mr. Fukao was interested in his own people everywhere, and it was his energy which led to the beginning of work among the Japanese in Hilo and Paauilo.

Long established Japanese work was carried on by the "Hawaiian Board" (outcome of the Congregational Mission) and the Methodists who spent large sums of money annually. In contrast, our work was hampered in its natural development by a lack of money and more seriously by a lack of men. Yet so great was the influx of Japanese and so promising was our mission among them that Bishop McKim on several occasions said that Bishop Restarick might select any man in the Tokyo District and he would be transferred if money were available for his support. Dr. Motoda visited the Islands in November, 1920; and made a report on the situation, emphasizing the importance of the work and the need of workers, but his suggestions could not be carried out.

Another group in Honolulu which attracted Bishop Restarick's attention were the Russians. As far as possible, the Church sought to minister to these people, but a priest who could speak their own language was needed. Accordingly, in November, 1916, [45/46] Bishop Restarick placed the matter before the Russian Archbishop in New York. A month later, the Rev. John T. Dorosh, a Russian priest, arrived bearing a commendatory letter addressed to Bishop Restarick. The letter ended rather remarkably: "Kindly take him under your jurisdiction for the time being and render him all the services and instructions for his work." This distinct recognition of the Anglican Communion greatly impressed the Cathedral congregation. Arrangements for the support of the work were made locally and a time for services was provided in Holy Trinity Church, but the work which began under so favorable conditions was not long to endure. A year later, nearly the whole Russian congregation had left Honolulu and Mr. Dorosh gave up the work.

Any account of the work centering around the Cathedral would be incomplete without some consideration of the educational enterprises which in the course of a few years developed into the most important work in Honolulu.

St. Andrew's Priory for girls, which for many years had been in charge of the English Sisters, was placed, on the coming of Bishop Restarick, in charge of several American laywomen, under whose direction the School was successfully maintained. In less than a decade the enrollment grew from some 40 pupils to nearly 150. The old Priory buildings, inadequate even from the beginning of the American regime, were utterly incapable of accommodating the developing School. Bishop Restarick was eager to secure new buildings and, to this end, purchased a choice site close to the Cathedral. Here the new building was erected and, in 1910, the School was moved.

Another of Bishop Restarick's hopes was to interest an American Sisterhood in the School and have them assume its charge. In 1917 he presented his proposal to the Sisters of the Transfiguration, of [46/49] Glendale, Ohio, and the next year three Sisters were sent out. One of these was a niece of the Superior of the Order and a granddaughter of W. A. Procter, whose interest in Hawaii was so largely influential in the development of St. Elizabeth's Mission.

The Priory, which is both a day and a boarding school, was designed especially for Hawaiian and part-Hawaiian girls, but there were always a few Chinese and a few white girls in attendance. The boarders came from all the islands and all the girls were apt pupils. The School has a record of which it ma) well be proud. In 1911, the Attorney General and the Juvenile Court Judge said that among the 800 girls who had been brought before them there had never been a St. Andrew's Priory girl.

A word may well be said here in regard to the need and value of Church Schools, especially boarding schools for girls, in Hawaii. Although the public school system was inaugurated under the American Government, no provision w as at first made for those who desired to go beyond the fifth or sixth grade. It also must be remembered that the vast majority of the pupils in the public schools were Orientals, and their difficulties with the English tongue tended to retard instruction. Hence, those who wished to advance normally were required, of necessity, to seek schooling elsewhere. The Church's schools provided such a place. But there were even more vital considerations. Bishop Restarick in discussing this question, said: "A man who was born on the Islands and returned in 1915, after a long absence, told me that the thing that impressed him most was the great improvement of Hawaiian girls due to the boarding schools. Another said to me, in 1902, that boarding schools for Hawaiian girls only made them more attractive as mistresses. Twenty years later, when he saw the progress made, he retracted what he had said. What has led to this improvement, as much as any [49/50] thing, is the change in economic conditions. In the times of Bishops Staley and Willis there were practically but two ways open to girls on leaving school. One was marriage, which all principals tried to arrange, the other was to take up with some man willing to support them without legal marriage, which is called 'marriage in Hawaiian style'. Today it is different. Employment is open to an educated girl in many directions. She can go to a training school for nurses, as many have done. She can fit herself for an office position or go to the Normal School and become a teacher. In all these and other capacities she has proved herself efficient, reliable, and as able to take care of herself as her white sisters. If a girl can earn a good living she is not in a hurry to marry the first man who comes along. She does not marry at fourteen or fifteen as her mother did. Boarding schools have been a wonderful help in instilling religious and moral principles."

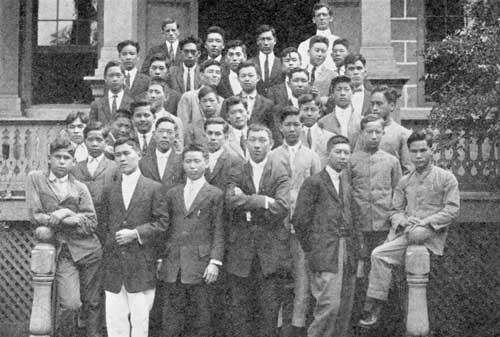

The other Church School is Iolani. Under Bishop Willis this had been a personal venture and when efforts to sell the school property to the American Church failed, Bishop Nichols closed the boarding department and moved the remnant to the old Pro-Cathedral. There were about 30 pupils in this day school when Bishop Restarick arrived in Honolulu. It was not long before many requests were received to place boys in the School as boarders. In order to meet this demand, a stone house in the rear of the Chinese Church was rented and later purchased. It is interesting to note that this house was the boyhood home of Samuel Chapman Armstrong who, in later life, founded Hampton Institute, the inspiration for which he had received in his boyhood observations of industrial training carried on in the Hawaiian Islands.

The School grew steadily. Under the leadership of a trained American educator, the School was graded [50/53] according to American standards and a High School department added. Some time later, industrial courses were introduced. With each improvement the popularity of the School increased, many applicants had to be turned away, and the congestion of the School itself became ever more acute. Many expedients were adopted to meet the growing need. An old Priory schoolroom was moved to the Iolani grounds for use as a dining room and class room, while additional class room space was found in the Davies Memorial Building and the basement of St. Peter's Church. Although the School was at a great disadvantage from lack of equipment. good work was done.

In 1902, Iolani students were predominantly Chinese, though there were always some Hawaiians, and as the years passed, Japanese were enrolled in increasing numbers. Iolani boys are found all over the Islands working in many capacities. Some are also, in China, Japan, and the United States. From among the graduates have come eight Chinese priests, while other former students included the Hon. Sen Wa, one time Mayor of Canton; Dr. P. K. C. Tyau, an Oxford graduate and one time adviser to the Peking Government; Dr. Lo Chang, also an Oxford graduate and for ten years Chinese Consul-General in London; and Dr. S. T. Tyau, a prominent physician on the staff of St. Luke's Hospital, Shanghai. Everywhere they have done credit to themselves and the School.

The provision of suitable living quarters for Christians of all races in his See city, was ever one of Bishop Restarick's gravest concerns. With the increasing number of Priory graduates attending the Normal School an acute housing problem arose, which the Bishop hoped to relieve through establishing a Christian hostel for girls studying in the city. A suitable piece of property was available on Emma Square which, through the generosity of George B. Cluett of Troy, N. Y., the Church was able to secure. The [53/54] Cluett House, as the hostel was named, was opened in 1913 and offers accommodations for about 35 boarders. Originally planned to provide a home for only Priory graduates, it has gradually taken in other approved young women of various races who are studying in Honolulu. The House has few rules other than that the girls agree to attend some place of Christian worship at least once each Sunday. It has been a most successful and helpful home devoid of the constraining atmosphere usually associated with an institution of this kind, and many girls look back on their years in Cluett House with very pleasant memories.

Thus, in 1920, Emma Square, with St. Andrew's Cathedral and the Bishop's House as the centre, might be considered a typical cross-section of the Church's work in Hawaii. Adjoining the Cathedral was Holy Trinity Church for Japanese and the Japanese Mission School. Close by was Iolani School, while on the other side of the Bishop's House was St. Andrew's Priory for girls. Just beyond the Priory was St. Peter's Chinese Church, next to which stood Cluett House. An impressive Church group, in 1920, not yet complete or adequate to the demands made upon it, but graphically indicating that at the "Crossroads of the Pacific," as throughout the world, the Church seeks to minister to all peoples.

This Cathedral centre was imbued with the missionary spirit. Hardly a congregation worshipping on or near Emma Square but did not become interested in people residing in more remote districts and suburbs of the city.

An offspring of the Cathedral was St. Clement's Parish. When the Rev. John Usborne was at the Cathedral, he conceived the idea of a church in the Punahou district of Honolulu as a chapel of ease to the Cathedral. Land was acquired; chapel, rectory, and parish house were built; and on the occasion of [54/57] Bishop Nichols' visit in 1902, provisional standing as a parish was granted. Upon the adoption of the Constitution and Canons, regular standing as a parish was accorded St. Clement's. Under the guidance of Canon Usborne, St. Clement's developed quietly and took a keen interest in missionary work. It was due largely to the efforts of the women of the parish that its indebtedness was gradually reduced and, in 1911, finally wiped out. The condition of the Chinese in Honolulu also attracted the attention of the women. As a result, in 1904, St. Mary's Mission for the Chinese was established within the parish boundaries. In 1917, Canon Usborne resigned. Under his successors the parish continued to prosper and in 1925 reported 215 communicants, an increase of over one hundred per cent during the past fifteen years.

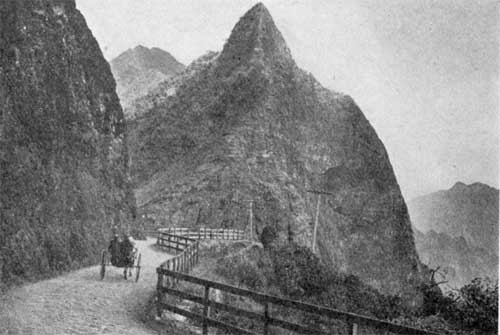

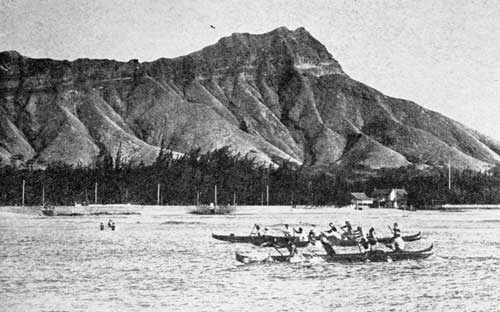

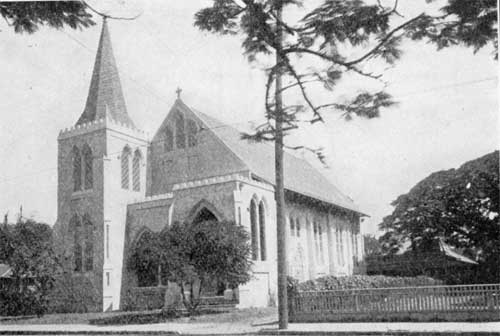

As St. Clement's may he considered a daughter of the Cathedral, so Epiphany Church may be regarded as the daughter of St. Clement's. In 1908, it was apparent that Kaimuki, a part of St. Clement's parish, was a growing suburb. A survey was made which resulted in the purchase, in October, 1910, of a centrally located lot on Tenth Avenue. Services were begun the following January in a private house until a mission hall could he erected. A Woman's Guild and a Sunday School were organized, and it soon became apparent that a church must be built. The universal opinion was that a stone church was desirable and that there was sufficient lava rock on the church lot to build it. On the feast of the Epiphany, 1915, ground was broken and six months later, on July 18, the first service was held in the completed building.

From the Hawaiian congregation of the Cathedral came the incentive to begin work among the Hawaiians in the Kapahulu district, Honolulu. In 1908, a woman of the Hawaiian congregation living in Kapahulu called attention to the need for a Sunday School there. No religious work of any kind was being done in [57/58] Kapahulu, and a Sunday School was accordingly begun. It grew so rapidly that it soon became necessary to move to a large, unused room in the barracks of old Camp McKinley. When, in 1910, the Rev. Leopold Kroll took charge of the Hawaiian congregation at the Cathedral, the work at Kapahulu, which was known as St. Mark's Mission, attracted his special interest. He was soon convinced that if this work were to be permanent it must have a home of its own. Accordingly, a suitable site was leased and a building which could be used both as a church and a day school was erected. When, on the Sunday after Ascension, 1911, the new chapel was dedicated, it was announced that the land upon which the building stood had been given to the Church. The following year a day school was begun under the direction of Miss Marguerite Miller (later Mrs. C. C. Black) and, in 1915, a separate schoolroom was built.

The influence of St. Mark's in the Kapahulu district cannot be measured by figures and, while much of the result may not be apparent, the lives of many have been touched with the truth of the Gospel. Situated at the foot of Diamond Head, an extinct crater which the United States has converted into a fortress, St. Mark's Mission--its chapel, day school, and dispensary--is the only institution which ministers to the children of the district.

It is noteworthy that the interest of the Chinese parish of St. Peter's was not limited to Chinese in their own district but extended to all Chinese wherever resident in Honolulu. When, therefore, in 1902, St. Clement's proposed beginning work within its parish boundaries, St. Peter's immediately became interested and rendered valuable assistance in the establishment and development of St. Mary's Chinese Mission, Moiliili. At Bishop Restarick's suggestion, a vacant store in Moiliili was rented and on December 8 the Rev. Kong Yin Tet and Yap See Young, warden of [58/61] St. Peter's, assisted by two women, began a Sunday School. Two years later, Mrs. F. L. Folsom, matron of Iolani, began a night school. Mrs. Folsom's interest grew until, in 1906, her entire time was devoted to this work.

The Mission was housed in a miserable shack with a leaky roof, and with its growth larger and better quarters were necessary. A large house was finally hired in Beretania Street, and this provided comfortable living quarters, a large room for the varied work of the Mission, and a room suitable for a chapel. About this time also, Mrs. Folsom began a day school for Chinese girls which was an immediate success with an enrollment of forty-four girls. The need of feeding these undernourished children was apparent and it was not long before the day school was providing its pupils with a good mid-day meal. So eager were the children to come to St. Mary's that it soon became necessary to limit the day school enrollment to 150.

Another feature of the work was a dispensary. This was begun in a small way to care for minor accidents and wounds of all kinds. In 1911, the Palama Settlement made St. Mary's the headquarters for a district nurse, who took charge of the dispensary.

In the meantime, Mrs. Folsom was transferred to Hilo and Miss Sara Chung and Miss Hilda Van Deerlin succeeded her at St. Mary's. From the first, they looked forward to the time when the Mission should have its own home and were ever alert for a suitable site. In 1910, a large lot with a good house upon it was purchased on King Street. A new building was planned and on May 26, 1912, it was dedicated. This event, occurring during the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Anglican Church in Hawaii, was honored by the presence of Bishop Willis. The new building provided a dispensary, three schoolrooms, one [61/62] of which was used as a chapel, and living quarters for three workers. The need for a chapel was very great but it was not until July 15, 1917, that St. Mary's Chapel was consecrated.

About this time also three little girls came to make their home at St. Mary's. Thenceforth other orphan and dependent children were taken in. Thus began St. Mary's Home, although the living quarters at the Mission provided not enough accommodations for the children. To meet this situation the sitting room was turned into a bedroom and beds were put in the hallway, on the porch, and everywhere that one could be put. Later, when a new schoolroom and assembly hall were built, one of the former schoolrooms became a dormitory.

The growing work to which a kindergarten was soon to be added demanded more helpers. To this need Miss Margaret Van Deerlin responded.

An important feature of the work was, of course, the Sunday School. With such devoted little missionaries as Seichi it is not surprising that 200 children were enrolled before many years had passed. Seichi was a nine-year-old boy who on his way to Sunday School a week or so after his Baptism met two boys going in the opposite direction. He asked them where they were going and upon being told "to the Buddhist Sunday School," he invited them to come to St. Mary's with him instead. They became regular attendants at St. Mary's and it was a great joy to Seichi when his two chums received permission to be baptised.

Another Chinese work, second only in importance to St. Peter's, and in which St. Peter's took a lively interest, was St. Elizabeth's Mission, begun in 1903 under Deaconess Drant. Shortly after Bishop Restarick's election, he received a letter from Deaconess Drant offering for service in the Islands. Much as he [62/65] wished to accept her offer, he had already engaged two women workers and was confronted by the problem of support. Accordingly, he told her the situation and suggested that she go to her friend, Mr. W. A. Procter of Cincinnati with the proposal that he employ her as his own missionary. Mr. Procter liked the idea and not only agreed to meet her salary and traveling expenses, but also to provide the general expenses of the work she intended to undertake. Thus began an interest in the Hawaiian Islands which was to mean so much for the future of all the work but especially for St. Elizabeth's House.

Upon her arrival in Honolulu, Deaconess Drant rented a house in the Palama section and began a night school for Chinese young men. This was immediately successful, and large numbers of young men came to the classes, in connection with which a short service was held every night.

The work prospered; a building of its own was an urgent necessity. Mr. Procter, who had followed the progress of St. Elizabeth's with intense interest, offered to purchase the necessary site. This was done and soon afterwards he provided the means with which to erect a church and mission house. The new plant was completed and consecrated on May 7, 1905.

In the meantime, the growth of the work made desirable the securing of a priest to assume its direction. An admirable man for this position was secured in the person of the Rev. W. E. Potwine, who arrived in Honolulu in May, 1904. A few months later, Deaconess Drant, ill from overwork, was obliged to resign. She was succeeded by Deaconess Sands, who had recently arrived in the Islands to undertake work at Iolani.

Under Mr. Potwine's direction, the influence and activities of St. Elizabeth's spread in many directions. A rest house for church workers (first at Waiahole [65/66] and later moved to St. Elizabeth's compound), and Procter Lodge, a home for young Chinese Christian men, were built. The success of the latter led to plans for cottages for married couples. The need for these had come about in this way. While at first the congregation of St. Elizabeth's was composed entirely of single men, they were beginning to marry Christian young women. Already there were Christian families connected with St. Elizabeth's and it was desired to get our Christian families out of tenements or undesirable neighborhoods into houses which they could obtain for a reasonable rent. When this need for cottages became evident, Mr. Procter, the benefactor of St. Elizabeth's, had died, and his family provided the necessary funds for the purchase of the remaining half block on which the mission buildings stood. It was planned to erect cottages on this land, the rental of which would be slightly lower than that prevailing elsewhere. This building of cottages on a large scale for people of small means was the first experiment of its kind in Honolulu and one which has been extensively followed. The model Chinese Christian cottages were among the chief points of interest to Church people visiting the city. On one occasion, the Bishop showing St. Elizabeth's to a New York Churchman was asked what was needed. Being told the remainder of the half block on which Procter Lodge was situated, he sent the Bishop a cheque for this purpose. This additional land made possible the erection of more model cottages.

Mr. Potwine directed St. Elizabeth's until 1915, when he decided that, for the sake of his family, he should take a charge in California. His removal from the Islands was not only a great loss to St. Elizabeth's but to the whole District. During his more than ten years' service there he had been Secretary of Convocation and business manager and assistant editor of the Hawaiian Church Chronicle. His wide experience [66/69] in Church affairs prior to his coming to Honolulu made him of greatest assistance to the Bishop during the formative years of the American Church in Hawaii. Two years after his return to the United States, he died.

At St. Elizabeth's, he was succeeded by the Rev. Frank W. Merrill. Mr. Merrill was a priest of wide experience. While a master at Iolani, in 1880, he was ordained Deacon and took charge of the work at Kaneohe, Oahu. Then followed years in Australia and the United States, where for nearly a decade he was a missionary among the Oneida Indians of Wisconsin. In 1911, he felt again the call of Hawaii and returned to take charge of St. Augustine's Mission, Kohala. Four years later he was transferred to St. Elizabeth's. For three years he labored unsparingly there until, following an operation, he died. Mr. Merrill's incumbency was marked by careful management which led to a large reduction of the debt on the cottages.