THE stole is one of the vestments covered by the Ornaments Rubric, and nowadays fulfils a twofold purpose. It denotes the rank in the ministry of the person wearing it by the manner in which it is worn, and it shows that the wearer is taking part in the ministration of a sacrament.

Its origin was much more humble, for it was originally a napkin (like the maniple or 'fanon') which servants of the sanctuary carried about, as a matter of convenience, over their left shoulders, and it was used for cleansing the sacred vessels. Gradually it came to be folded until it became a long narrow strip, and as such it is still worn by deacons over the left shoulder, since their office is to assist the priests in the conduct of divine service.

The priests wore scarves or neck-cloths worn over both shoulders, and these in time also became stoles, as we see them in use to-day. But they must not be confused with the scarves or tippets worn by the clergy for the choir offices, to which reference will be made later.

The stole appeared in Spain as the insignia of deacons in 563, and of priests and bishops in 633.

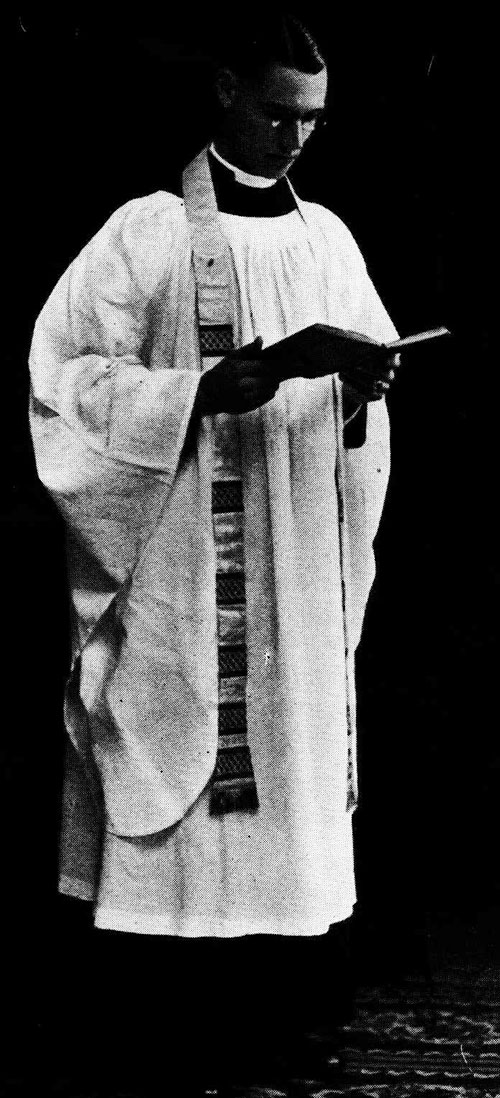

In the Eastern (Orthodox) Churches the stole is called [3/4] the 'epitrachelion' (for priests) or 'orarion' (for deacons), and is worn at all services and in a greater variety of ways than it is in the Anglican and Roman Catholic Churches. In the Church of England a deacon always wears his stole over the left shoulder and tied at the right side, whether it is worn with surplice or albe (Plate I). At a deacon's ordination to the priesthood it is usual for one of the assisting ministers to untie the stole immediately after the laying on of the bishop's hands, and to lift that part of the stole which has been across the ordinand's back over his right shoulder, so that when he rises from his knees the newly-ordained priest wears his stole in the manner that denotes his new rank in the ministry; that is to say, with both ends hanging down in front of his shoulders. When a priest wears the Eucharistic vestments he crosses the ends of the stole X-wise over his breast and secures the ends in that position with the ends of his girdle. When, however, a priest is acting as deacon (or gospeller) at a solemn celebration of the Holy Communion he wears his stole deacon-wise, since he does not cease to be a deacon when he becomes a priest, for the higher order includes the less.

A bishop usually wears his stole uncrossed at all times, whether over the albe beneath his chasuble or over his rochet.

In the Eastern Church, where customs vary, in the Syrian Melchite Church, for instance, a reader (a layman) wears a stole with the middle part passed horizontally across his chest, the ends being passed under his arms, brought over the shoulders, and then tucked under the horizontal part. A subdeacon wears his stole under the right arm, the ends being brought up over the left shoulder, crossing there and hanging [4/5] down at the left side, back and front. A deacon's stole hangs over the left shoulder, with the ends hanging down at the left side, back and front. An archdeacon (that is, a priest acting as principal deacon on certain occasions) wears his stole as a deacon does in our Church.

The Eastern priest's epitrachelion is shaped differently, the two inner edges being joined together, or a wider piece of material is worn as a long panel with a slit at the top through which the head is passed. A belt or girdle is sometimes used to hold it in place. (Photographs of Syrian Melchite clergy wearing stoles in all the different positions described, as taken by Dr. J. H. Arnold in Baghdad, will be found in the Alcuin Club Tract XVI, The Uniats and their Rites, by Stephen Gaselee. Published by A. R. Mowbray & Co. Limited.)

The best and most convenient form of stole is that in which it was worn in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries; that is, not more than about two inches across, of the same width throughout except that the ends are slightly splayed out. It should not be less than about nine feet long, for the ends should show below the full, long Gothic chasuble, which is much the most beautiful form of that vestment. These long, narrow stoles are flexible, fall easily into place, and are. comfortable to wear. For use with a surplice a very similar stole may be used, but it may for convenience be about a foot shorter in length (Plate 2).

With the coming of the Renaissance chasubles were narrowed, cut down both at the sides and at the ends. Stoles then became broader and uglier and less convenient, sometimes with huge spade-like or square ends. One of the Popes, disapproving of this tendency, forbade the cutting down of chasubles (which often ruined ancient, [5/6] beautiful, and valuable vestments). But the clergy of his day continued with the evil work, taking care to cut their chasubles down a few inches at a time. As the chasubles grew shorter, more 'and more of the ends of the stoles appeared hanging down below and proclaimed the guilt of the vandals, who, to avoid this, began to pull the middle of the stole away from the neck and down their backs until in time they even tucked the middle of the stole, which should have been at the back of the neck, into the girdle at the middle of the back. Some clergy, fond of 'unintelligent imitation,' still do this, probably without the least idea why they do it!

The stole may be richly embroidered from end to end, it may have, a series of 'headings' made with contrasting material (see Plate 2), it may be embroidered at the ends only (see Plate 3), not necessarily with crosses, or it may have headings at the ends (see Plate 4). The ends are generally finished with a fringe. A seam in the middle is sufficient to mark the middle of the stole--anything else is unnecessary, and a large cross in that position only too often proclaims that the stole has been put on in a hurry and is "not being worn with the two ends level and evenly balanced. Nor is it necessary for a clergyman of clean habits to have a strip of lace tacked on to the stole, for the narrow type of stole sets properly and white lace soon looks grubby and untidy and, since it is a bother to take it off, wash it, and tack it on again, often looks very dirty indeed.

Stoles should only be worn at the ministration of sacraments. They should not be put on for preaching sermons (though a priest or deacon wearing the Eucharistic vestments will, of course, retain his stole in the pulpit after putting off the outer garment), nor [7/8] hung down the back; and it also came to be used as a

pocket--

'And then he drew a dial from his poke.'

The hood and the cape were worn separately at first, but later they came to be joined together, so that they could be put on both at once. In the fourteenth century the liripip was lengthened, and men of fashion wore it reaching almost to the ground. The next development was to wrap the long typet around the throat as a scarf, and later the hood turned into a kind of turban, wound round the head or made up into a hat, with the liripip projecting. After passing through various other changes the liripip was separated from the hood and was worn by itself round the shoulders, and so it became the scarf.

The scarf, having originally been part of the hood, was, of course, made of the same material--hence it was of silk for doctors and masters and of stuff for bachelors, and the Canon Law extended the use of the stuff scarf to non-graduates, who had no hoods. Those who are entitled to hoods naturally wear their scarves with them, and the use of the scarf or tippet is now confined -to those clerks who are in holy orders. The original relationship between scarf and hood is least obscured when the hood is made in the beautiful cape shape, the use of which is now by no means uncommon (see Plate 5).

The hood and scarf are worn over the surplice for Mattins and Evensong and other non-sacramental services, and the scarf is also worn with cassock and gown as the formal canonical dress of the clergy. The deacon wears his scarf in the same way as a priest. Bishops wear scarves over their chimeres, which are sleeveless gowns worn over the episcopal rochet.

[9] It should be noted that when the hood and scarf are worn together the scarf should be put on after the hood.

A stiff or thick material for the scarf detracts from its beauty and its ability to drape itself in natural and graceful folds over the shoulders. There should be no tailor-made pleats in the scarf, but the middle part should be gathered in the hands and placed around the neck (see Plate 5). To stitch the scarf and iron it into artificial, regular folds spoils its appearance, and moreover concentrates the wear upon one or two places, lessening its life and usefulness. The scarf looks better and drapes better if it is made rather wider than is customary in the church-shop variety.

The ends of the scarf should not be 'pinked,' for that serves no useful purpose. It is much better that they should be hemmed.

Finally, we may note, in passing, that the stole and the scarf denote the clerk in holy orders as distinguishable from the lay clerks, such as servers and choir-men

Plate 1. Deacon wearing Stole over Apparelled Albe and Amice.

Plate 2. Priest vested for Solemnization of Matrimony.

Plate 3. Stoles with Embroidered Ends.

Plate 4. Stole with Headings.

Plate 5. Minister vested in Surplice, Hood, and Scarf.