It is impossible in the space at our disposal to make of these notes a treatise, however short, on the history and science of armory. We must assume that our readers have some elementary knowledge of the subject, or, if they have it not, we must be content to refer them to books that embody the conclusions of the most modern and accomplished writers on this subject. Such are Mr. Oswald Barron’s articles in The Ancestor (Constable, 1902—05), and his Heraldry in the last edition of Encyclopedia Britannica; the late Sir William St. John Hope’s Grammar of Heraldry (Camb. Univ. Press), and his Heraldry for Craftsmen and Designers (Hogg, 1913); and Professor F. B. Barnard’s chapter on ‘Heraldry’ in that very valuable and important work, Mediaeval England (Clarendon Press, 1924).

All of these are the works of masters of their subject, illustrated by references to original sources as well as by drawings and photographs of mediaeval examples.

The following notes deal with the application of heraldry to the uses of the Church in architecture, seals, tiles, and glass, in brasses, monuments, and paintings, in needlework, and in carvings in wood and stone.

By the end of the twelfth century heraldry had become systematized. It was already the subject of a definite code of laws founded on considerations of practical utility as much as on aesthetic principles; and in that sudden and brilliant out-flowering of art that marked the thirteenth century its decorative potentialities [2/3] were speedily recognized. As early as 1257 the designers and carvers of that age had produced the splendid series of shields which adorns the spandrels of the wall-arcades of the aisles behind the quire of Westminster abbey church.

Towards the end of the century heraldic decoration was being applied to the exterior of ecclesiastical buildings, as, for instance, on the gate house of Kirkham priory in Yorkshire, built between 1289 and 1296. Akin to the Westminster shields are the six that the fourteenth-century builders placed high on the nave walls of St. Albans abbey church; and a few years later the presbytery, qui re, and arches of the central tower of Yorkminster were similarly adorned with a series of great shields of the arms of benefactors of that church. To the fifteenth century belong such works as the armorial ceilings of the cloisters of Christchurch, Canterbury, and of the Divinity School at Oxford; and so the process matures and develops until it reaches its culminating point of splendour in the gatehouses of S. John’s and Christ’s, and the chapel of King’s college at Cambridge.

The introduction of heraldry into English episcopal seals [3/4] follows a course which enables us to place them in groups that become more and more elaborate in design as time goes on.

From 1237 to 1318 we find these seals displaying, not shields of arms, but, charges from the bishop’s arms placed beside or upon his figure which, during that period and for nearly a century onward, was the central device of the composition. For example, Walter de Cantelo, bishop of Worcester (1237-66), flanks his standing figure with fleurs de lis from his arms; Anthony Bek, bishop of Durham (1284-1311), places upon his vestment the millrind cross from his shield.

This fashion led naturally to the display of the bishop’s arms upon a shield, and we come next to a well-defined group, of which the seal of Fulk Basset, bishop of London (1244-59), is a typical and very early example. Here the bishop stands on an architectural corbel characteristic of the period, in front of which is a shield of Basset’s wavy bars. This style of seal lasted until the end of the next century. In later examples two shields of the personal arms are found, as in the beautiful seal of Robert Braybrook, bishop of London (1382-1402).

An exceptional design, in that it gives a very early example of the arms of a bishopric, is that of Walter of Louth, bishop of Ely (1290-98), which displays the full length figure of the bishop standing under a canopy of late thirteenth-century architecture, with a shield of the three crowns of Ely in a little niche below his feet.

Slightly later another group of seals, of which that of Walter Reynolds, archbishop of Canterbury (1314-27), is a typical example, introduces the arms of the king as the only heraldic ornament. This type is developed in seals such as that of Robert Wyvil, bishop of Sarum (1330-75), where two shields of the royal arms hang on the pillars of the canopy under which the bishop stands. Contemporary with this design is an elaboration of it, of which a good example is the seal of Alexander Nevill, archbishop of York (1374-88), who flanked his standing figure with the king’s arms and his own.

Another large group which falls between the years 1345-88 shows shields of the bishopric and of the bishop’s own arms. [4/5] Henry Despenser, the warrior bishop of Norwich (1370-1406), had a seal of this character; so had William Courtenay, archbishop of Canterbury (1381-96); but the figure of the bishop is no longer the principal element of the design. The elaborate canopied niche which occupies the greater part of the seal is filled with a representation of the Trinity, or a Majesty, or by two or more saints, while the bishop has shrunk to a tiny half-length figure kneeling in prayer in the base of the composition.

In the seal of Simon of Sudbury, archbishop of Canterbury (1375-81), the martyrdom of S. Thomas is the central motive; two angels hold shields of the king and the see, and below the little episcopal figure at the bottom is a shield of the archbishop’s own arms. Thomas Arundel, archbishop of Canterbury (1397-1414), seems to be the first English prelate to show in his seal the impalement of the arms of the see with his paternal coat. Heraldry entered very largely into the decoration of the flooring-tiles of churches. One of the earliest and certainly the most magnificent of examples of this practice is seen in the four-tile pattern of the arms of Henry III in the chapter house of Westminster. The date of its making is the middle of the thirteenth century. Nearly every great church throughout the land retains something at least of the armorial tile pavement that once beautified it. Tewkesbury, with its thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth-century [5/6] tiles showing heraldry of Clare and Despenser, Newburgh and Beauchamp, Berkeley and Audley, stands pre-eminent. To name even a few of the many other churches fortunate in this respect would be wearisome; but the vigorous draughtsmanship and the bold execution of mediaeval flooring-tiles must by no means be left out of account if the student would appreciate the decorative quality of heraldry and its manifold application.

Ancient armorial glass still survives in sufficient quantities to prove how largely it entered into ecclesiastical schemes of decoration and how gloriously it served its purpose. So much has perished either by natural decay or by wanton destruction that it is unwise to speak positively; but from surviving armorial glass it would seem that heraldry was first introduced into church windows in the third quarter of the thirteenth century. The row of shields at the bottom of the west window of the nave of Salisbury is certainly some of the earliest armorial glass in England—seven great shields of the arms of Henry III, his queen Eleanor of Provence, his brother Richard of Cornwall, S. Louis of France, Warenne, Bigod, and Clare, that once shone in the windows of the chapter house.

Though heraldry in glass is found in every part of the land, Yorkshire is the happy hunting ground for the lover of that beautiful form of church decoration. In York minster and in many of the city churches, also at Sherburn, Ingleby, Raskelf, Thirsk, Wensley, Bolton Percy, Cowsthorpe, Dewsbury, and Kildwick, to name only the most important, are wonderful collections of heraldic glass.

Canterbury cathedral is extraordinarily rich in this respect; so is Bristol cathedral. At Long Melford, in Suffolk, is much fine armorial glass; and in Great Malvern priory church there is in the north window of the north transept a valuable series (circa 1500) of angels holding shields charged with emblems of the Passion.

In all mediaeval glass the student should remark particularly the extreme ingenuity employed to make the strong black lines of the leadwork emphasize the heraldic patterns and outline the charges. We must refer him to Philip Nelson’s valuable treatise [6/7] on Stained Glass in England (Methuen, 1913) for further information.

Memorial brasses form so important an element in the internal decoration of mediaeval churches that a word may be allowed as to the way in which heraldry enters into their design. Of those that remain the brass of Sir John d’Abernon (circa 1290) in Stoke Dabernon church in Surrey is the oldest in England. The simplicity and directness of this early work is as significant and characteristic of its period as it is beautiful. As you compare it with such a brass as that of Eleanor Bohun, duchess of Gloucester (d. 1399), in S. Edmund’s chapel at Westminster, you mark how in the course of a hundred years the increasing skill of the brass engravers has brought into this art a most exquisite and delicate elaboration of technique, but no more power and no more beauty than were manifested in the work of their predecessors.

Mention of Westminster reminds one that to see monumental heraldry at its finest there is no need to go beyond the walls of that incomparable church. John of Eltham, Edmund of Lancaster, Aveline de Forz, William de Valence, Aymer his son, Lewis Robessart and hundreds of others of the great ones of the earth,—there they lie sleeping their long sleep, their resting places gorgeous [7/8] with heraldic adornment. No other church in the world can show the like. Nowhere else can you see so clearly the glory and the wonder and the meaning of heraldry.

But monumental heraldry is incidental rather than structural decoration of a church. Consider, then, how heraldry has been utilized in the painting of the structure. Consider the wooden ceiling of the quire of St. Albans cathedral church, with its multitude of painted coats of arms. This is work of the fourteenth century, grave and stately in its severely formal arrangement, yet splendidly gay and vivid in the play of its brilliant colouring; and, of its kind, it is unsurpassed in Europe. Compare it with the carved and painted ceiling put up by Bishop Fox (1501-38) in the presbytery of his cathedral church of Winchester. Here you see, in that bewildering medley of arms celestial and terrestrial, badges, gartered shields, sacred monograms, crowned initials and devices of every kind, heraldry at its wildest and most extravagant, decadent and yet supremely decorative as it always was in the great days of the art.

Coming at last to the ‘ornaments of the ministers’ we find here, too, how heraldry has been employed for their special adornment.

Most ancient and most precious is the famous Syon cope, now after many wanderings safely housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum. This wonderful example of English needlework of about the year 1290 has a broad orphrey of fourteen coats of arms of nobles and great folk of that day embroidered on roundels and lozenges. Round the whole of the semicircle runs a border composed of a stole and a maniple of the same period sewn end to end and embroidered with a series of forty-five lozenges of arms.

A little later in date are the stoles belonging to Lord Willoughby de Broke and the stole and maniple in the possession of Miss Weld of Leagram; all three were shown at the Heraldic Exhibition of the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1916. The stoles contain respectively thirty-eight and forty-six, and the maniple eighteen coats of arms of English families, set closely to form patterns of the utmost brilliancy and splendour. At the same exhibition was shown Col. J. E. Butler-Bowdon’s chasuble, with its cross-shaped orphrey [8/9] (of circa 1474) of crimson velvet richly embroidered in gold and coloured silks with eight shields of Stafford and allied houses, Clare, Woodstock, Bohun, and Miles of Gloucester, all supported by the swans of Buckingham and set on a running pattern of branches, leaves, and columbine flowers tied together with Stafford knots.

An inventory made in 1315 of the ornaments of Canterbury cathedral mentions copes and chasubles, albes and stoles in great numbers, many of them decorated with heraldry, the most notable, perhaps, being a vestment given by king Philip of France, and made, appropriately enough, of blue cloth embroidered with golden fleurs de lis. Very noteworthy, too, are vexilla pro rogationibus of which there were eleven, ten of these processional banners being worked with heraldry of the king, the earl of Gloucester, the earl of Surrey, and Hastings.

The Westminster inventory of 1388 names among carpets, silken cloths, copes, and other pieces embroidered with heraldry, a frontal used at the funeral of Edward III with the arms of France and England in red and blue velvet woven with golden leopards and fleurs de lis, and a cope of red velvet with gold leopards having a border of blue velvet woven with gold fleurs de lis. This was [9/10] once the property of John of Eltham, second son of Edward II, and is, it will be observed, a cope of his well-known arms.

A S. Paul’s inventory of 1412 enumerates many heraldic vestments, cushions, copes, and orphreys for albes and amices, among which were three amices given by Queen Isabel, of red velvet worked with the arms of her husband, Richard of England, and with little figures of angels which were the supporters of the royal arms of her father, the king of France. All these, alas, have vanished beyond recall; but the mention of them makes a stately finish to this very summary survey of the application of armory to the decoration of ecclesiastical objects in the middle age.

These notes could have been extended indefinitely, but enough has been said to show how largely heraldry entered into every scheme of church decoration. It is only natural that it should have done so. The knowledge of it was universal; it was everybody’s language, a pictorial shorthand which all the world understood and loved for its brightness and decorative quality. In the same spirit we of to-day may still use and appreciate it. But it needs to be handled with the utmost care. For most of us have lost that clear vision of proportion, scale, and balance, that fine simplicity of design, that effortless instinct for pure line which the men of an older time possessed in so remarkable degree. We have lost that youthful capacity to use heraldry naturally and serenely and joyously which was theirs. The fact is that we have grown old and sophisticated, timid and self-conscious. Where to-day is the designer bold enough to make, or the governing body of a great church unconventional enough to use, for a king’s funeral, a frontal of gules and azure all a-sparkle with gold embroidery, such as the men of Richard II’s time saw no incongruity in using? Tradition shackles our imagination, and makes us afraid of colour and brightness and humour in our churches. And it is to be feared that until we are content to go back to the art of the middle age and to study it quietly and humbly with sympathy and a seeing eye, we can never recover the playfulness and elasticity, the gaiety and loveliness that the sure instinct of the men of the old days recognized as the essence of heraldic art.

And yet it can be done, if only designers will dare to let [10/11] themselves go, and patrons will encourage them to make use of heraldic decoration.

In the making and adornment of vestments, in which the Warham Guild specializes, really good work has been accomplished in recent years, much of which owes its rich decorative effect to the inspiration of ancient work.

The cope and mitre made for the archbishop of Wales and worn by him at his installation form an instructive example. The cream-coloured figured silk brocade of the cope has orphreys of a plain dark blue silk embroidered with a Celtic pattern of gold thread and cord, carrying eight regularly disposed shields of the arms of the bishoprics of the province of Wales arranged in pairs: the cross with its five cinqfoils of St. Davids at the shoulders, the crossed keys of St. Asaph at the level of the waist, the crossed staves and mitres of Llandaff lower down, and the sprinkled bend and pierced molets of Bangor towards the bottom of the orphreys. A little shield of St. Asaph appears also on the band of material which, in the fashion of a morse, holds the cope across the breast of the wearer, and again at the back of the mitre. The hood of the cope forms, too, a stately array of Welsh ecclesiastical armory. It shows a design of a cross embroidered in the form of a tree, charged at the intersection with a shield of instruments of the Passion, and cantoning shields of St. Asaph, St. Davids, Llandaff, and Bangor.

Heraldry might very well be reintroduced into the adornment of stoles. If perhaps not to such an elaborate extent as in the mediaeval examples mentioned on an earlier page, it might take the place now and again of the crosses and meaningless floral pattern which too often satisfy the designers and workers of these ornaments of the minister. The writer well remembers a purple stole made a few years ago in which two little shields of Passion emblems, a different shield for each side, replaced with happy effect the usual crosses.

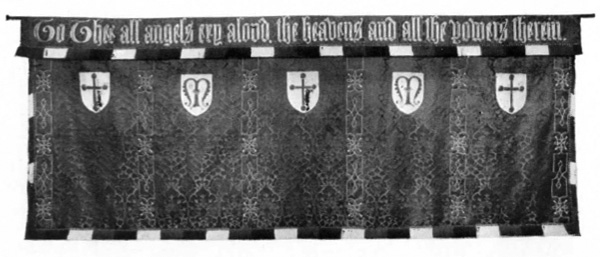

Equally effective and decorative are the shields of saints in the two frontals here figured. That designed by F. E. Howard for the church of S. Michael at Wigan is adorned with five shields charged alternately with the pommy cross attributed in some old rolls of arms to the archangel and the initial M of his name. The second frontal, designed for a church dedicated in honour of S. Andrew, has four shields alternately of the saint’s saltire and the A of his name, separating three large monograms of the Holy Name in finely drawn Gothic letters.

Heraldry forms the motive of the decoration introduced with splendid effect in the dorsal made for Fairford church. This hanging of five tall panels of silk brocade, separated by narrow strips of figured material, is enriched by a series of ten shields disposed along its upper part in a continuous band of glowing colour, and linked together by a chain pattern of flat gold. In the northernmost panel are the well-known armorials of the great houses of Clare and Despencer, which once held the earldom of Gloucester. In the next panel are the arms of the Newburghs, earls of Warwick, accompanied by a shield of the crossed keys of S. Peter. The central panel has two shields (half obscured by the tabernacle-work of the reredos), emblematic of our Lady, her monogram on the northern side and her arms of the pot of lilies on the other. South of the reredos in the first panel are two coats of arms, the first the dragon and lion of Tame of Fairford impaling the [12/13] engrailed bend and fleurs de lis of Dennes of Gloucester, the other of Lygon impaling Dennes for William Lygon who in the sixteenth century married Eleanor, daughter of Sir William Dennes. For the southernmost panel are two shields, the one of Lygon, the other of Lygon impaling Grosvenor for William, seventh Earl Beauchamp, and Lady Lettice Grosvenor, his wife.

This array of heraldry, besides performing a splendid decorative function, is also an important historical and topographical document, for while the seven shields, gay with the emblazonments of great English families, tell the tale of the lords of the manor, the two shields of our Lady declare the dedication of the church, and the crossed keys of S. Peter tell that the place is in the bishopric of Gloucester.

In the reredos designed by G. Kruger Gray, F.S.A., for Princes Risborough, the heraldry is confined to the cresting of carved, painted, and gilded wood that surmounts the design. In [13/14] the middle of it is a crowned shield of the arms of Edward the Black Prince; to the north are the mitred arms of the bishopric of Oxford in which the parish now is; to the south are those of the see of Lincoln in which Princes Risborough was formerly included; while the rest of the cresting is composed of a closely set series of golden fleurs de lis of France and leopards’ heads of England, again referring to the prince whose title is embodied in the name of the parish.

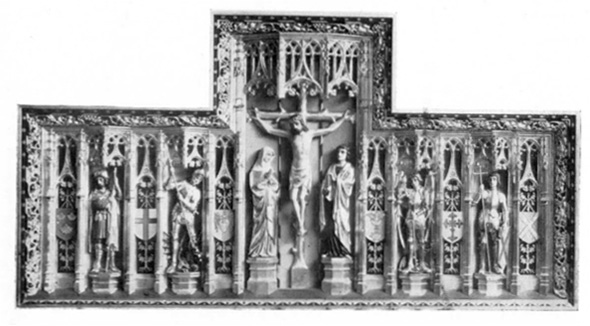

The carved reredos of painted and gilded oak, made for S. Gabriel’s church in Swansea, consists of a tall central compartment containing the Crucified with S. Mary and S. John, flanked to north and south by niches holding alternately shields of arms and figures of saints. On the north side stand S. George, S. Patrick, and S. David, with the familiar shields attributed to the patron saints of England and Ireland on the right hand of those figures, S. David being symbolized by the shield of the see that bears his name. On the south side are S. Andrew, S. Nicholas of Barri, patron of seamen, and S. Michael the archangel with their appropriate arms beside them. To complete the tale of armorial symbolism there is in the niche beside our Lady her shield of mater dolorosa, while the niche to the south of S. John’s figure encloses a shield charged with his emblem of the deadly chalice.

Of similar design is the reredos of the church of S. James at Silsoe in Bedfordshire. Here, besides the central element of the Crucified with His attendants and their arms, are, on the north side, figures of S. James in palmer’s weeds and S. George in full armour with their arms, and on the south S. Michael and S. Alban with shields of the arms that mediaeval piety assigned to them.

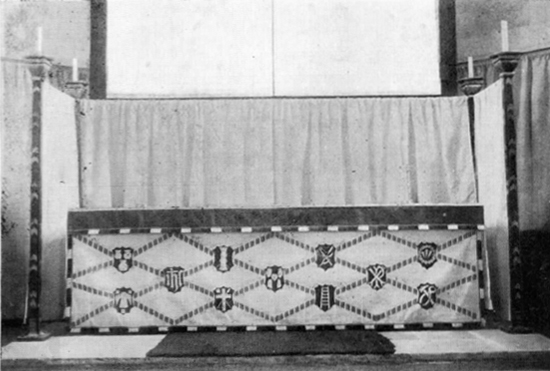

All these examples show heraldry in all the glory of colour and metal, embroidery and appliqué work, sumptuous and magnifical. That it may be equally effective in the humbler vehicles of simple white linen and stencilled colour is shown in the frontal designed by the present writer for S. Mary’s, Primrose Hill, and executed by Miss Phyllis Burges. Here the effect is obtained by a design of black cords crossing diagonally with eleven shields in red at the intersections of the cordage pattern. These shields are charged as follows: in the upper row the forty pieces of silver, the pillar of [14/15] scourging, the scourge crossed with the sceptre of reed, the nails and the crown of thorns; in the middle row IHS, the five wounds, and XP; in the bottom row the seamless coat with the dice, the cross, reed and sponge and the spear, the ladder, and the hammer and pincers.

In such ways heraldry may be employed as once it was for the embellishment of things ecclesiastical; and these notes are as much a plea for the seemly revival of its use as an indication of the many ways in which it may serve to the glory of God and the adornment of His sanctuary.

Cope and Mitre Made for the Archbishop of Wales.

Altar Frontal for S. Michael’s Church, Wigan.

Altar Frontal for S. Andrew’s, Kirkby Malzeard.

Portion of Dorsal at Parish Church, Fairford.

Reredos at S. Gabriel’s Church, Swansea.

Altar with Lenten Array, S. Mary’s, Primrose Hill, N.W.