THE reception of the Body and Blood of the Lord in Holy Communion has from apostolic times been considered at once the duty and the privilege of Christian people. The sacred rite was one of the chief, if not the chief, purpose for which the followers of Christ assembled themselves together. The reception of “the food called Eucharist ... no common bread and common drink . . . but flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh”—this, as Justin says within fifty years of the last Apostle’s death, was the weekly privilege of believers.

The privilege being so great, it is not surprising that those who were unable for any good reason to be present at the Sunday meetings should desire none the less to lose as little as might be of the blessing attaching to them. Accordingly the same writer tells us that the sacred elements were conveyed to the absent.

The practice of Communion apart from the Eucharistic [2/3] service was widely increased in the dangerous times of persecution, and after the peace of the Church, the custom of taking the Viaticum to the dying had become well established—always under the control of the bishop.

METHOD OF RESERVATION

Our information as to the conduct of services and the arrangement of churches during the first six centuries being so scanty, it is natural that there should be but little information at our disposal touching the place of reservation and the receptacle used for the purpose.

As to place, for quite a long period the reserved Eucharist was kept, not in the church but in the sacristy. In the early days of Christianity, when persecution was not ancient history, practical considerations of safety weighed far more than notions of reverence or fitness. It is not, then, a matter for surprise that the reserved Sacrament should have been kept, along with other sacred and precious things, in the safest place in the building. Nowadays it would hardly be thought seemly to reserve the sacred elements anywhere than in the church itself. This in fact is the practice both of the Latin and of the Orthodox Churches.

The need of some provision for communicating the faithful, especially the sick and infirm, outside service time is being increasingly felt in the Anglican Communion, and seems likely to be recognized in the Alternative Prayer Book. When the practice is allowed, it would seem natural that, as far as place is concerned, [3/4] we should follow the use of East and West and reserve in the church, and not in the sacristy or in some secluded place set apart for this purpose only.

THE RECEPTACLE OF RESERVATION

If the Sacrament is to be reserved in the Church, the subjects where and how at once arise. Recent discussions have brought this question very often to the notice of the clergy. There are three different ways of keeping the reserved Eucharist commonly known at the present day. These three are the Altar Tabernacle, the Suspended Tabernacle or Hanging Pyx, and the Aumbry or Sacrament House in the wall of the Sanctuary. And there are, broadly speaking, four considerations or principles which need to be borne in mind.

(a) Tradition.

(b) Convenience.

(c) Fitness.

(d) Architectural Consideration.

(a) Tradition.

The Altar Tabernacle is characteristic of the counter-Reformation abroad, and its frequency is comparatively modern. There are scarcely any instances of its use in England before the Reformation. For this reason it is not part of the English tradition to which the Ornaments Rubric directs our attention. It is, however, general, though not quite universal to-day in churches of the Roman rite. Its use has very recently been adopted in [4/6] a small number of Anglican churches, usually without the approval or sanction of the bishop.

The Altar Tabernacle might perhaps be regarded as the Hanging Pyx let down and resting upon the altar. The word, “tabernacle” signifies a temporary dwelling, and was applied to the receptacle of the reserved Sacrament on account of the linen veil which hung all round the actual vessel of reservation, giving the appearance of a tent.

(The official instructions of the Roman Church still demand that the metal, stone, or marble receptacle for the Sacrament “must be entirely covered with a Veil with an opening in the front to allow of access to the door.” [See Directions for the use of Altar Societies and Architects, compiled under the direction of the late Cardinal Vaughan. New Edition, Revised and Enlarged. By G. B. Tatum and Osmund Bentley [1912], p. 36.] This order seems to presuppose the absence of gradines, for strict compliance would be impossible in the majority of modern tabernacles which are often mere cupboards let into the gradine and veiled only in front.)

The Aumbry (loculus in muro) or Sacrament House [6/8] was by no means the most common use in England before the Reformation, though it was more frequent in Scotland and the Low Countries. It is highly probable that some Easter-Sepulchres were used for reservation. [In connection with the history of the Aumbry as a place for reserving the Sacrament the following quotation from the late Edmund Bishop, a Roman Catholic ecclesiologist, is suggestive. It occurs on page 38 of his Liturgica Historica (Clarendon Press, 1918):—“Before ending, I will ask, what of that prescription in the Caeremoniale Episcoporum as to the Reservation of the Blessed Sacrament, not at the high altar of cathedrals, but at a side altar? It is not prescription by mere arbitary fiat, but a prescription that has been derived from Roman practice. Somehow it recalls to me, an item of ‘discipline’ now passed and gone—the ‘loculus in muro.’ Is there some actual and real connection between this and that? Or is this rapprochement merely wayward and irrational fancy on my part?”]

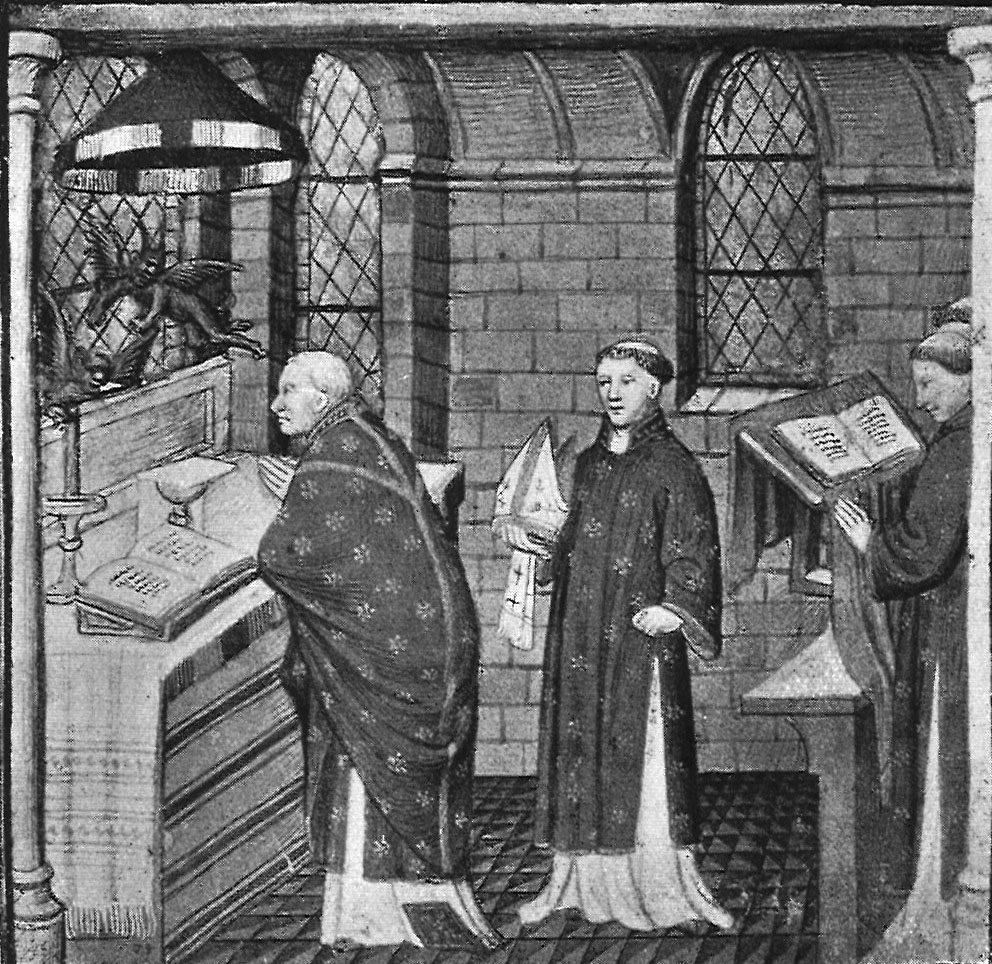

During the two centuries preceding the Reformation the more usual method of reservation in England was the Hanging Pyx or Suspended Tabernacle. It was also common in some places on the Continent, especially in France, where its use was not infrequent as late as the seventeenth century. Plate I shows the method of suspension, though the somewhat large canopy prevents even a glimpse of the veil covering the actual pyx. (The picture is taken from an early fifteenth-century French MS., and reproduced by permission of the Alcuin Club.)

(b) Convenience.

In many ways the Altar Tabernacle is a convenient arrangement. The consecrated elements can easily be removed or renewed by the celebrant without his having to leave the altar.

The Aumbry is similarly convenient and easy of access.

The Hanging Pyx is at first sight the least practical from the point of view of the priest, but this inconvenience is more apparent than real. Modern contrivances make it perfectly easy for any authorized person to have access to the Sacrament, while this method is far more secure against any unauthorized approach. Many Altar Tabernacles have been broken [8/10] into, but no present-day example is known of any successful attempt to rifle a Hanging Pyx.

(c) Fitness.

The sacred character of the reserved elements, “the figure (figura) of the Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ”—to quote one of the oldest Eucharistic writers—demands reverent treatment. How is this to be secured? One way is to lock the reserved Sacrament in a special chapel. But this would seem to be an excess of reverence, and out of harmony with general Christian sentiment, which has aimed at harmonizing the Sacrament, when reserved, with the other sacred objects of the Church. Catholic devotion, like Catholic theology, is a balance of different and sometimes seemingly opposite elements. In a Christian Church the centre of worship is the altar. “We might almost say,” writes the Benedictine Abbot of the Monastery of S. Paul Without the Walls at Rome, “the essential motive and raison d’être of the whole building.” [The Sacramentary. By Ildefonso Schuster. Translated by A. Levelis-Marke. Vol. I, p. 162.] It is natural, then, thatefforts should be made to connect with the altar everythingelse most sacred, but in such a way as not toobscure the essential dominance of the place whereonthe Eucharist is offered. The two most sacred thingsin early times were the Gospel and the reserved Eucharist.“Upon that holy table was kept the codex of theGospels, the letter of the New Law, while above ithovered the life-giving Spirit who was to breathe into it[10/12] the breath of life. That volume, and that eucharisticdove, holding hidden within its breast the consecratedspecies, signified the whole New Testament whose lawis love.” We quote the Abbot again.

From this it will be seen how satisfactory the Hanging Pyx is in expressing the exact nuance of devotion that can rightly claim to be Catholic. The Aumbry serves the same purpose almost equally. It has not the advantage that the Hanging Pyx has, of holding the Sacrament as it were in suspense, during the time when its main purpose is not being fulfilled. But it is closely associated with the altar, and in no way interferes with its centrality.

The Altar Tabernacle, fixed upon the mensa, and screwed into its surface, is entirely lacking in these devotional advantages, while it almost inevitably, as experience shows, invades and interferes with the glory and purpose of the altar, which becomes little more than a shelf for the reception of the tabernacle. The proportion of Christian piety is destroyed by an undue isolation and almost aggressive emphasis upon one aspect only.

(d) Architectural consideration.

The Altar Tabernacle developed and became common during the baroque and rococo periods of architecture, and it came from Italy. To no stage in the indigenous development of North European architecture has it ever belonged, and it formed no necessary part of an altar eyen in the Renaissance style. It is part of the arrangement of the altar which spread from Rome in [12/13] post-Reformation times, and with it went the row of six lights and one or more gradines. Hence also the reredos in its strict and original sense of pictures or imagery rising immediately from the altar, disappeared, or became sundered from, the altar, raised aloft and coarsened in detail. The Altar Tabernacle breaks the reredos, the six lights hide it, the shelf spoils its proportions. With it the altar tends to become the mere adjunct and base of its own ornaments: it ceases to be like a table, and becomes a kind of side-board in form. Obviously the Altar Tabernacle is an incongruity and a violation of artistic fitness in an ancient English east end, with its long altar and low reredos filling the space beneath the great east window. Even where the window was high enough to admit of large figure work above the reredos, or where the window did not exist, as occasionally in a side chapel, the Gothic tradition maintained the reredos in its integrity as the immediate decoration of the altar, in strict proportion with it, never big enough to dwarf it, and without shelves beneath it. It is, moreover, hardly correct to say that the Altar Tabernacle is the Renaissance equivalent of the Hanging Pyx or the Sacrament House, because splendid examples of both the latter ornaments have been made in the Renaissance style.

In conclusion the canonical aspect of the matter must be referred to. The assertion that the right to reserve the Eucharist is inherent in the parish priest’s cure of [13/14] souls is, in view of the plain direction of the Prayer Book as to the disposal of the Sacrament, at best very temerarious. The rubrics of the Prayer Book are not cautions but commands. But in any event, it must be universally agreed that the directions of the bishop of the diocese touching the place and method of reservation are final and binding.

Hanging pyx in the Fifteenth Century.

Hanging pyx in position.

Hanging pyx, with small inner pyx, to contain the Sacrament.

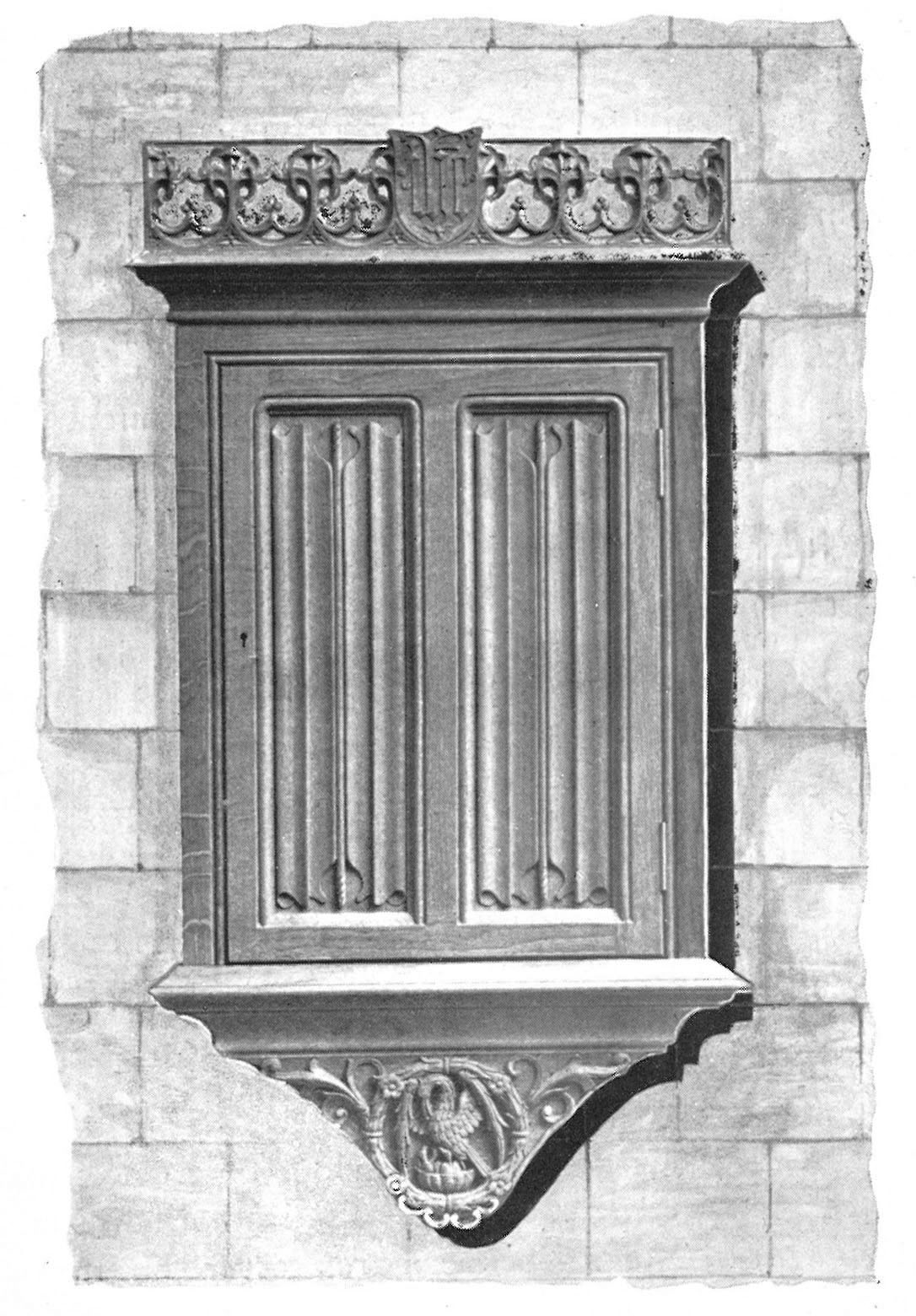

Aumbry front in carved oak, fixed in the North wall of the Sanctuary.