IT has occurred to me, that some memorials of four brothers, all distinguished by talents, industry and perseverance in their respective stations, might not only be acceptable to their surviving relatives, but afford a useful example to other young men, entering into life with perhaps less prospect of advancement. It will be seen in the following pages that these brothers had few advantages of birth, fortune or patronage. Our parents were, at the time of their marriage, suffering from the displeasure of our paternal grandfather, whose displeasure was excited by the refusal of his younger son to contract a marriage with a first cousin, the heiress of a large fortune. The lady proposed for our father's wife was without much education, though most amiable and assiduous in the discharge of every allotted duty. She was moreover, unattractive [3/4] in person, being rather deformed. Her disposition was quiet and retiring. My father, though esteeming her highly, felt that she could never be a suitable companion to him, or a mother capable of instructing her children. He had seen and loved another, the daughter of a very superior man, who had early trained her in a love of literature, and above all, in reverence for religion, and in a careful study of the Holy Scriptures.

He therefore refused to ratify the contract made by his father for his marriage with his cousin, and in consequence, his name was wholly omitted in his father's will, although he succeeded" by entail, to the landed estate at Richmond. The family plate, the furniture of the house, and all other personal property were bequeathed to his two sisters, both of whom lived to an advanced age. They both often kindly assisted their brother in his difficulties, but as our grandfather survived seventeen years after his marriage, the early education of the family was a source of great anxiety. An allowance of £300 a year was all my father received on his marriage, but [4/5] by industry in his profession as a barrister, and by becoming Reporter of Cases in the King's Bench, he increased his income. He also published a useful legal work, "The Abridgment of the Law of Nisi Prius," which was for many years a text book with the profession till in 1857 such changes were made in the statutes and practice of the Courts, it became comparatively obsolete, after having gone through eleven editions. When I state that nine children were born to my parents, six of whom lived to grow up; four sons educated at Eton, and afterwards at Cambridge, I need not add, that much prudence and self denial were required to meet the expenses of so largo a family. Moreover the necessity my parents felt of giving up society, to avoid its attendant encroachments on their time and resources may be added to the number of disadvantages under which the brothers laboured from their earliest ago. But, as has often been observed, those who have no means to depend upon and who feel that it must be through their own exertions that they can obtain any position, are far more likely to succeed than [5/6] those, who not being obliged to work for their own support, and living in wealth and luxury, are apt to fancy that they shall ultimately be provided for without any effort of their own. I well remember the late Bishop Blomfield when asked why he worked so hard at the University, even injuring his health by his unremitting exertions, answering, "Because I know I had nothing else to depend upon." He and many others who attained the episcopal dignity, began life under great difficulties, which they surmounted by energy and perseverance.

I may mention as one of the chief elements of my brothers' success in life, their strong affection for each other: often have I heard the eldest brother relate how, to conquer the timidity of his third brother, always in delicate health, he would take him on his back to their bathing place at their first school at Ealing, and protect him from the gibes and petty persecutions to which his sensitive and peculiar nature exposed him. To our excellent mother, my brothers owed their early training, not only in religious principles, but in the elementary [6/7] part of their education. I give in her own words an account of her eldest son's progress, from extracts entitled "Portraits of my dear children," found after her death.

"1813.

Little William, (only seven years of age,) finished the Book of Proverbs in March, learnt the Latin Grammar, down to the Paradigms, twice, and began it the third time."

"Jan., 1817.

William, not quite eleven, in the Greek Testament and in Virgil at school. Understands Geography very well and has designed several maps. Has made great progress in drawing, and writes and dances very well. He adheres to truth strictly, and is well acquainted with the Bible. His gentle forbearance and the kind assistance he affords his younger brother (George) are truly admirable, and his perfect freedom from all vanity and self conceit. His character from his master at school has been uniformly excellent during the nearly four years he [7/8] has been under his care, and on one occasion his conduct was particularly noble."

The brothers were all first placed at Ealing, as they respectively attained the age of seven years, a period now considered too early to subject a child to the hardships of school life, but it does not appear, in their case, to have been attended with any evil consequence.

The school was then conducted by Dr. Nicholas and his son, and for many years enjoyed a high reputation. Within very few years I have seen prospectuses of the present school, enumerating the many eminent men who had been educated there, including my four brothers. But the old building has long since disappeared and the establishment of High Schools in so many large towns has materially diminished the number of private schools.

My father, and other parents of pupils, educated at Ealing, always highly appreciated the thoroughness of the instruction there given.

My eldest brother, William, was placed at Eton in June, 1821. I give in my mother's words an account of his career there.

[9] "1821.

"William (our eldest surviving child) having been at Eton a year, during that time, been twice 'sent up for good,' and received an excellent character from his master and tutor. He has several times received the Holy Sacrament, and given many instances of great reverence and respect for sacred places, ordinances and books, and a constant desire to attend Divine worship. No hasty or improper expression ever escapes his lips, although his disposition is lively, and he delights in all amusements and recreations suited to his ago (15). His character is so much esteemed by all who know him, that his society is eagerly sought for their children by all parents who are acquainted with his worth. Although possessing superior talents, his modesty is not at all diminished by all these distinctions. It only receives additional lustre from the bright colours which surround it."

Besides her careful attention to the mental improvement of her children, my mother always strove to make their home happy, by promoting all manly [9/10] exercises and "healthful play." They wore encouraged to bring home friends to share their recreation. No reproofs were ever made, if they were detained by any expedition on the river, and if (as was often the case) they came home drenched to the skin by immersion in the water, a supply of dry clothes and hot mutton chops was always in readiness for them, thus inducing them to look on their home as their best refuge, and never to resort to any place of public entertainment, where they might meet with unsuitable associates. One of their companions, since gone to his rest, often told me he should never forget his delight at being received after a thorough wetting, (caused by the upsetting of their boat) and provided with a suit of my father's clothes, in which he made an amusing figure.

Few now survive who can recall these happy gatherings, but I have repeatedly narrated the circumstances, as a proof of our parents' judicious treatment of their sons, and in several instances, I have noticed the injurious consequences resulting to youths who were not so happily situated. One dear [10/11] valued friend of my eldest brother, who died, alas! by his own hand, attributed the depression under which he laboured and which led to the fatal end, to never having had a happy home.

It was most delightful to see the interest taken by their father in all the studies of his sons. Every difficult passage was submitted to him, and he supplied them with quotations and with information which no books could so well afford. On Sundays, the cheerful gatherings round the table, presided over by my mother, were devoted to researches in the Scriptures, some one subject being given, on which to find passages illustrating it. She was engaged in drawing up an Abridgment of the Scriptures, and her children were interested in searching for references, or in extracting from commentators, passages which threw light on any disputed point. We never found Sunday wearisome, so varied were the occupations of the day, all bearing upon the most important duties. Attendance at Church was never compulsory, but generally allowed as a reward for good conduct. Religion was never made [11/12] distasteful by long prayers or lectures, or by undue strictness of behaviour. Sunday was considered (as it was meant to be) a type of Heaven, including rest from worldly business, and preparation for that "rest which remaineth for the people of GOD."

No lessons, except the Collect for the day, were ever required on Sunday, but on Saturday we always repeated the Sermon on the Mount, and, till we were confirmed, the Church Catechism. Thus grounded in the faith, and knowing the Scriptures from their childhood, can the subsequent devotion of my two older brothers to their Master's service, be matter of surprise? I am aware that many persons object to this early instruction in Divine truths, but my parents wisely considered that unless the good seed were sown early, it would bear no fruit, that passages of Scripture, learnt when young, would abide in the memory, and although not at first understood, might, as our Christian poet has taught us to believe, be afterwards appreciated--

"Dim or unheard, the world may fall,

And yet the heaven-taught mind

May learn the sacred air and all

The harmony unwind."--Keble.[13] In October, 1824, my brother William was entered as a student at St. John's College, Cambridge, having for his private tutor, the Rev. William Pakenham Spencer, who was also appointed tutor to the young Duke of Buccleuch, then entered at the same college, but who refused to give up my brother, for whom he had formed a strong affection, which remained unabated till his lamented death. My mother thus alludes to this valued friend,--"He (my son William) has been blessed with a very agreeable friend, who has greatly lessened the labor of application, and to use his own words, "he has rendered the study of mathematics, a pleasure, instead of a fag."

Writing to the mother of Mr. Spencer, in 1846, my dear brother says,--"I have been reading with the greatest interest and pleasure, Mr. Hamilton's letter to Mrs. Ollivant (sister of Mr. Spencer) and have been much struck by the similarity of his feelings to my own." Spencer must have been to him, exactly what he was to me, an elder brother, anxious for my success at any sacrifice to himself. I do [13/14] indeed feel that the greatest part of my present comfort and happiness in life has been bestowed upon me through the kind assistance of my beloved friend. I can trace back all that I now enjoy of worldly good and of domestic happiness, and still more, of honourable employment in the Lord's vineyard, in great measure to his help at College, which enabled me to gain a place of credit in College and University examinations. God grant that hawing been so blessed by His mercy, I may not be altogether unfruitful.

My brother preached the funeral sermon, on Rev. xiv. 13, after the death of Mr. Spencer, at Starston, near Harlaston, in Norfolk, of which parish he was Rector, and I subjoin the following extracts from it, "I have known your beloved Pastor for more than twenty years, and consider his friendship as one of the chief blessings of my life. He was my guide and counsellor, to whom I owe more than I can express, and it is a comfort to me to be able to tell you of the testimony of his life, and of his death, that he was one of those who are blessed [14/15] because they die in the Lord. When he was first appointed your minister, he told me he wished for time for study, to obtain far fuller and deeper views of the Gospel dispensation, than he had hitherto done. This earnest study of God's Word was continued, on one visit I found him engaged in the study of St. Paul's Epistles. When I saw him last winter at Ventnor, sickness and weakness did not prevent him from being interested in the same pursuits and equally ready to give advice and assistance. His love for God's House you all know, his anxious endeavours for its outward decency and befitting adorning: his devout performance of the public prayers, his faithful earnest preaching, in which he declared to you "all the counsel of God." You also know his earnest efforts for your welfare in private. I do not say that your minister was without infirmity, but that he was an honest, sincere man, acting on the highest principles, firmly, constantly and perseveringly for a long course of years. I may also speak of him as a faithful friend, an affectionate son, a kind brother, an upright [15/16] magistrate--such was the testimony of his life--he lived in the Lord. We have also the testimony of his death, so far as extreme weakness and illness permitted it to be given. At collected intervals he requested the reading of the scriptures and prayers, while he had yet sufficient strength to enjoy them. He responded to verses in the Bible which were repeated to him: when it was said, "The Lord is my Shepherd," he answered "What then shall I want?" again, "My heart and my flesh fail," he responded "But God is the strength of my heart, and my portion for ever." Within the last few moments of his death, he requested those who were praying to "go on," and the friends who were kneeling around his bed, heard his last "Amen." And of this testimony of the death we may say of this beloved friend "Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord." I have thought that this account of the friend to whom my brother owed so much, ought to have a place in these memorials of his career. Here too may fitly be inserted the sonnet written on the death of Mrs. Spencer, mother of Mr. Spencer, by my dear brother, Feb. 27th, 1850.

[17] Fair rose the morn, and brightly shone the sun,

As up the church-crown'd hill thy form we bore;

Sorrowing that we should see thy face no more,

Yet still rejoicing that thy race was run;

And there we laid thee near thy honour'd son,

By thy lov'd husband's side, while all around,

Within that little spot of hallow'd ground,

The early spring flowers told of winter gone,

And joy returning, pledges of that time

When the dark days of sorrow, sin and fear,

Shall pass away before the vernal prime

Of earth transformed to blissful Paradise;

When all, thus sown in tears, in joy shall rise,

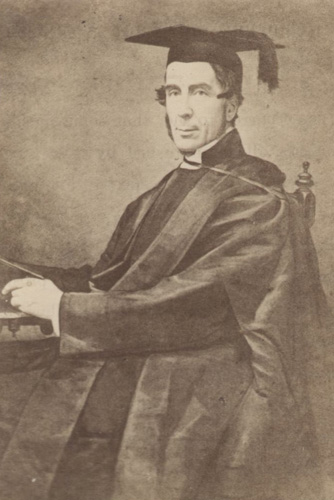

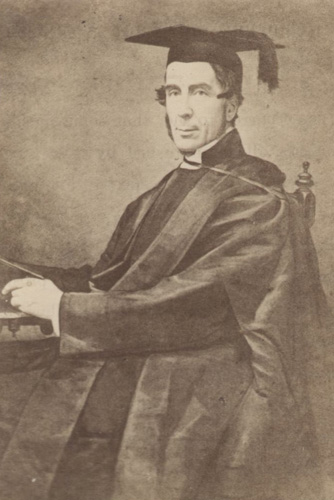

And bloom with Christ, in Heav'n's Eternal Year."____ EXTRACTS FROM MY MOTHER'S JOURNAL. "Our dear eldest son, who went to Cambridge October, 1824, has gladdened the hearts of his parents, not only by his distinguished talents and success, but by his uniformly excellent conduct. Last July, 1825, when we visited Cambridge to witness his recitation of his Prize poem (the Greek one), Dr. Wood, then Master of St. John's College, congratulated his father, not only on the honour he had obtained, but on his excellent conduct. He gained a College Scholarship soon after he went to [17/18] Cambridge. He gained the rank of 1st of the 1st Class, the Theme prize, and the prize for being the best reader of the lessons, and the most regular attendant at Chapel. In the Long Vacation of 1825, he requested to be permitted to study with Professor Scholefield, and allowed himself a very short portion of the Vacation for recreation. His diligence was crowned with success, for in February, 1826, he was unanimously elected University Scholar on Lord Craven's foundation. On the 19th February (his birthday) he arrived in London, (where his father had a house and chambers), and laid his honours, with true filial piety, at his parents' feet. He was in the neat examination, again 1st of the 1st Class. He obtained the prize for Themes, Declamation and verses, and in the summer of 1826, the three Brown's medals were adjudged him, for his Greek and Latin Odes, and for his Epigrams; (a success which has only thrice been achieved in the course of 100 years. )* [*From Dr. Wood's Memoir of Professor Selwyn, prefixed to the Pastoral Colloquies.] In 1827 he gained the medal [18/19] for the Greek Ode. In 1828 he came out as 6th Wrangler and 1st Chancellor's Medallist. In 1829, he was elected to a Founder's Fellowship of this College. He was ordained in 1829, and in 1831, presented to the living of Branstone, near Grantham, by the Duke of Rutland, to whose son (Lord Granby) he had been Tutor three years at Eton. He was in 1833 made Canon of Ely by Bishop Sparke, which position he retained till his death. In 1846, he resigned the living of Branstone for that of Melbourne, near Cambridge, which was in his gift as a Fellow of St. John's College [changed to Canon of Ely in text]. He had the hope of establishing a regard for the Church, in a parish which had been much neglected on account of the non-residence of its Vicars for several years. This preferment he resigned in 1853, and appointed to the Vicarage, the Rev. Fitzherbert Jenyns [changed to Fitzgerald Jengens in text], son of an old friend who had been for many years a Canon of Ely.

In 1855, he was elected Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity, which office he retained till his death; having refused to accept the Deanery of Ely which [19/20] was offered to him on the death of his brother-in-law Dean Peacock, in 1858, not wishing to relinquish his duties as Professor, in which he took the greatest interest.

Two enduring monuments of my brother's exertions remain in Cambridge. The first, is the Chapel of St. John's College, which was built at his suggestion and by his influence. The second, which he did not live to see realized, the erection of the Divinity Schools. To form a fund for this latter object, he annually set apart £700 of his income, as Lady Margaret's Professor, and now that they are completed, and affording the much needed accommodation for the Professors and Students we may apply to him the inscription in St. Paul's on Sir Christopher Wren:--

"Si monumentum requiris, circumspice."

His death was accelerated by an accident in 1866, from which he appeared to recover for a time, though paralysis was gradually developed, and his useful life did not extend to the allotted age of man.

[21] To the last he was occupied in writing in support of the Christian faith and doctrines he had through life maintained, and had prepared lectures on the pastoral office, to be delivered in April, when he was seized by his last fatal illness.

In the Appendix will be found several poems written on different occasions, proving the versatility of his genius, and ready command of language.

The Latin poem, written just after the accident, which ultimately caused his death, was widely circulated at the time, but has never been published. In the interesting memoir of his life prefixed to the edition of his last work, "Pastoral Colloquies," by Dr. Wood, President of St. John's College, many details will be found of his public speeches, which are not suited for this private memorial---in which also it is impossible to speak fully of his varied talents, and indefatigable industry in their improvement.

Here can be recorded his unvarying kindness to all around him, his readiness to aid the struggling, to cheer the dispirited, and to comfort the afflicted. [21/22] A letter is now before me, in which a friend speaks of his having been the greatest comfort in a time of affliction to herself and family--and much more might be added to bear testimony to his willingness and power to impart the truest solace to the wounded heart.

Rarely is seen such a combination of superior talents with so perfect a sympathy for the weak and suffering. His parochial visits, both at Branstone and Melbourne were highly appreciated. He often reminded one of Goldsmith's beautiful picture of the "Country Clergyman," so perfect was his manner of reading the service:

"At Church, with meek--yet unaffected grace,

His looks adorn'd the venerable place;

Truth, from his lips, prevailed with double sway,

And they who came to scoff remained to pray.___ EXTRACTS FROM JOURNAL KEPT BY MY DEAR MOTHER DESCRIBING A VISIT TO BRANSTONE, IN 1836. "The blessing, which attended my dear son's exertions was apparent on Sunday, September 11th, [22/23] when forty persons partook of the Heavenly Feast of Love, and I heard two old people observe how different the attendance was, compared with what it had heretofore been, when only two or three old men and women were the communicants. I am thankful to record that I hear my dear son's praises in every cottage which I visit. One poor woman who had lost an infant, he immediately visited, and gave her a little book. When I called on her, she said to me, "I hope Mr. Selwyn will come again; I hope my child is an angel in heaven. Oh, Ma'am, Mr. Selwyn will shine as a bright angel in heaven." A neighbour of her's spoke of him in the highest terms; saying, that Mr. Selwyn gave instruction to all who needed it, and that she often told her children that she could not put them out in the world, if it were not for Mr. Selwyn's money, who paid for so many children coming to his school. I have heard of his paying for many children before he came to reside on his living. Another spoke of the great pains my son and daughter-in-law took with the children. Another, that when anyone was in [23/24] distress he was sure to visit them,--be they who they might. Another, that she had heard with great alarm, that he was going to be taken from them, and that she had observed that it was a judgment on them for not having been thankful enough for such a minister. Another said, what a fine discourse we have had, adding that she was sure they could not have a better minister.

On Sunday, September 4th, 1836, my dear son, having a cold and cough, his dear father read the lessons, and it was a very interesting sight to see father and son employed in the same sacred office, which gratification was repeated in the evening service. On my dear husband reading the Lessons, one of the congregation observed, "And, Sir, what an utterance!"

On my dear son pronouncing a solemn benediction at the conclusion of his discourse, my heart expanded with gratitude for the spiritual comfort and great blessings vouchsafed during this peaceful visit, and I heartily pray that they may not have been bestowed in vain, and that the remembrance of them may never be effaced from my mind.

[25] The following Extract from a Letter written to me by Miss OLLIVANT, daughter of the late BISHOP OF LLANDAFF, and niece of Mr. SPENCER, will be read with interest.

____ "I have always felt it one of the privileges of my early life, not only to have known such men as Professor Selwyn, and Professor Blunt, but to have received so many proofs from both of the kind interest they felt in me as my father's child, and my uncle's niece. I remember how kind Professor and Mrs. Selwyn were when they took me on a little tour from Llandaff, by Merthyr, Brecon, and Monmouth, and again in visits at all their various homes; and I still possess a book on botany, and one of Archbishop Trench's, given to me by the Professor to help me in my reading. I think it was in our last visit to Vine Cottage, and after his serious accident, that I recollect his explaining the Transit of Venus by a model he had made out of a La Grace hoop and some croquet balls.

[26] I have never forgotten the expression of his face at St. Mary's Church on the Sunday in that visit. I happened to look up during the Bidding Prayer, and caught sight of it. It was like an embodiment of adoration and intercession, and seemed to reveal to me the secrets of a soul already in another world. But long before that visit, when only a girl of fifteen, I recollect once making a list of the good people I know, with, by each name, the grace which seemed to me to mark each one, that in that special virtue one may try to follow their good example. I cannot find it now, and I do not remember who all the good people were, but Professor Selwyn was one,--by his name I wrote "a heavenly mind."

[27] APPENDIX TO CHAP. I.

____Lines written in consequence of a conversation between Mrs K. and the Author, in which Mrs. K. had urged the propriety of the Abolition of Montem, and the author had argued strenuously in favour of its continuance, 1832.

____ Farewell to thee, Montem! the daylight is gone,

And all save the joys of remembrance are flown.

On fifteen-arch bridge, the last carriage I hear,

And the shout from the "Christopher" dies on my ear,Farewell to thee Montem, they say 'tis the last,

But I will not believe it till three years are past;

And then, if I find that dear Montem is gone,

I'll go to Salt Hill, and keep Montem alone,--I will not believe it, the gay and the wise,

In defence of dear Montem, indignant shall rise,

The voice of old Eton shall sound in the hall,

And the provosts shall start from their frames on the wall.I will not believe it, the old and the young,

The rich, and the poor, the canaille and the ton,

The returning of Montem, with happiness greet,

All save the head master, and fair Mrs. K.,Oh! yes, thou shalt still be our dearly-loved scene,

For thou hast been honoured by King and by Queen.

Recorded, and sung of, in prose and in rhyme--

But most thou are honoured and hallowed by time.[28] Who got the first Montem? Who knows of the year

When the first Montem ensign, our standard did rear?

Thou art ancient as college's time-honoured pile,

Thy beginning is lost like the springs of the Nile;What wonder, then, is it I love thee so well,

Dear Montem, whose origin, no one can tell.

Oh! ask me not reasons, it lies in my heart,

'Tis because I love Eton, and thou art a part.But, oh!, there are reasons one thousand and one,

Yet still would I love thee though reasons were none,

Thou art joyous and ancient, I cannot say more,

I love the things lov'd by our fathers of yore;'Tis because thou art dazzling and gay as the fly,

That sports in the sunshine, and flutters to die;

'Tis because thou art short-liv'd and dear as the flower,

That blooms in the noon-day, and dies in an hour;'Tis because thou art chivalrous, gallant and bright,

All graceful and brave, like the newly-dubbed knight;

Thou art fresh with remembrance of days that are gone,

And the joys of past Montems are blent with thine own;I thought, as I girded my sword on my thigh,

I'll be true to my country and King till I die;

I vow'd as we followed our flag round the yard,

Through life the bright honour of Eton to guard.Oh! glad is the morning that gathers once more,

The friends whom dear Eton united before:

How I love to see shaking hands warmly, and well,

Those who cut one another, or bow in Pall Mall.[29] I love the Long Walk, where the four-in-hands stop,

Their bonnet, and mantle, and countess to drop.

I love the School-yard, when the thronging crowds close--

For I know they're Etonians who tread on my toes.I love to see old faces mingled with new,

Fair ladies, and majors, and boys at one view.

I love the bright eyes, and the smiles that abound,

Far brighter at Montem than all the year round.Then I love to see coronets jumbled with carts,

And pole pressing sword-case, all moving by starts.

I love the plumes waving on Arbour Hill ridge,

And the long line from Hersehels' to Willow-brook Bridge.Oh! the march is delightful, in dust, or in rain,

And ofttimes, and oft, may I go there again:

And I love to see mothers with babes held on high,

The swiftly twirl'd flag on the hill-top to spy.I delight in the gardens, where restless and gay--

Scarlet coats, and bright damsels, like fairy-land stray.

And the sister, forgetful of Willis's Rooms,

Walks proud by her brother's ephemeral plumes.And what tho' some newspaper's critical eye,

A few incongruities chance to descry

Albanians, and Highlanders, Lancers, and Moors,

Robin Hood's Men, and Pages of Louis XIV.What tho' wig and gown'd wisdom* would fain set us right,

Say can it be folly, where all find delight;

And tho' with our pleasure some folly appears

'Tis dulce desipere, once in three years.

[*Sir Lancelot Shadwell.][30] What tho' we are destin'd to hurry and toil,

To drip in the rain, or in sunshine to broil;

Though bonnets are damaged, pelisses are torn,

They will all be renewed by the next Montem morn.Farewell to thee Montem! Return in three years;

With crowdings, and crushings, with flutters and fears,

Barouches, and bonnets, swords, sashes, and salt,

And let them pay double, who still will find fault.Farewell to then, Montem! and bright be the day,

That calls us again to be happy and gay.

Farewell to thee Montem! and dear Mrs. Keate,

At many more Montems I hope we shall meet.___________________________________________________________________________ Funeral of SIR WILLIAM FOLLETT, July 4th, 1845, at Westminster Abbey.

___I stood within that venerable Dome,

Where lie the mail-clad Templars,--'twas a day

Of funeral rites, and scarce had pass'd away

The throng that follow'd him to his silent home--

Lamented Follett--open was the tomb,

And there amid long ranks of mouldering clay,

Each coffin mark'd with names of honour, lay

The sad remains of him, the newly come.

Farewell! my soul is wiser for the sight,

Each minute in that vault is better far

Than years above, for with a deeper might,

Than ever moved the Senate--or the Bar--

The still small voice, within death's dread abode

Speaks to the heart, "Prepare to meet thy God."[31] THUNDERSTORM AT ELY. Midnight, August, 1819.

____Oh! Ely, 'twas a glorious awful sight,

When in thy hallowed aisles, and solemn tower,

In the dark stillness of the midnight hour--

Th' Eternal roll'd the thunder of His might,

One minute dark as death, the next all light.

I've seen thee, when the sun, at highest noon,

Illumined every vault, and when the moon

Slept on the fretted arches, silver bright:

And I have heard the pealing organ's swell--

Hymning high praise, and soothing mortal care.

But never was my frame so thrill'd as when

Those lightning flashes, momently did tell,

"E'en thus the Son of Man shall come again,"

I bent my knee and bowed my soul in prayer.___________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSOR SELWYN'S LATIN THANKS, 1867.

_____DOMINO PRCANCELLARIO

ET

ACADEMIAE CANTABRIGIENSI.

____Vobis exopto, qua non fruor ipse, salutem

Effundens almâ pro genitrice preces;

Languidus, e lecto; sed non languentia vota;

Aegreti insolito corda colore tument.O Patres, Fratesque, sacratae Lucis alumni,

Non leve momentum est, quod tulit una dies:

Plena inter vitae commercia, plena laborum,

Tempora, ad aeternas procubuisse fores;

Et subito lethi affinem sensisse soporem;

Haec sunt quies animum tangit ad ima Deus.[32] Vidi etenim, lapsu quamvis confusus iniquo

Quam vigil et fervens iste Paternus Amor;

Qui regit errantes stellas moderamine summo,

Et sine quo passer nullus in arva cadit.

Et sensi, fratrum pietas, e fonte perenni

Quam laeto arentes irriget amne locos.O utinam dignas possem persolvere grates,

Vobis qui e durâ me relevâstis humo; (1)

Vobis, qui curâ vigilanti, atque arte medendi, (2)

Fovistis laesi membra caputque viri;

Vobis, quos scalâ angelicâ conscendere coelum

Et laticem ex AGNI promere fonte juvat.Et tu, qui, juvenum rapidissime, non ita justo

Tramite, seu nimium praepete raptus equo,

Sive ipse impelleus, lapsûs mihi causa fuisti,

Tu mihi, sub Domino, causa quietis ave!

Sed precor! hoc posthac reminiscere; carpe sinistram;

Dextram occurrenti linquere norma ubet.Omnibus ex animo grates! det MAXIMUS ILLE

Omnibus aeterna luce et amore frui.GULIELMUS SELWYN,

Dom. Margaretae in Sacra Theologia Lector.(1) W. Kennedy, King's Coll.

Ravenscroft Stewart, Trin. Col.

W. H. Anable,

J. Halls, [both] Of the Pitt Press.(2) G. E. Paget, M.D., Cain's College,

C. Lestourgeon, M.A, Trin. Coll.[33] INCIDENT IN A MISSIONARY BISHOP'S TRAVELS.

____A Johnian Bishop in New Zealand wood,

Finding no host to give him bed or food,

Was kindly lodged by two of porcine breed,

Who left their straw to rest his weary head.

But lo! returning at the dead of night

A friendly grunt is heard upon the right,

And on the left a snout salutes his cheek;

Which moved the Chaplain in great wrath to speak,

"O friends and Maories! This is infra dig,

"Our Bishop's cheek insulted by a pig!

"He must be killed and cook'd"! The Bishop smiled,

And said, "My friends! in judgment be more mild;

"These pigs have been my friends, have lodged me well,

"And of their kindness I shall often tell;

"And for the kiss, you do not understand 'em

It is the pigs' admission ad eandem".W. S.

___________________________________________________________________________ TO THE MEMORY OF WILLIAM SELWYN, ESQ., Q.C.

BY REV. W. OLIVER.

____Lines suggested by a visit to his Tomb, at Rusthall Common.

31st March, 1870.

____No sculptur'd Marble, dear departed Shade,

Adorns the spot, where thy remains are laid.

No costly Monument to catch the eye

Calls on the Stranger here to stop and sigh.

A simple Cross, recumbent, void of show,

Marks where thy Ashes rest in faith below.

Beneath, as border, fewest words relate

Thy Name, Birth, Death: and thy Profession state![34] But though no sculptur'd Marble marks the spot,

Nor word of praise--for such thou needest not!

'Tis vain on Stone and Marble to rely,

And thus the ravages of Time defy.

Such Monuments themselves must yield to fate,

Just like the Men they would perpetuate.

Thou hast a Record of a better kind,

If men are known by those they leave behind.Thy Sons and Daughters, as we all may see,

Reflect what Virtues shone so bright in Thee:

One Son, illustrious for his Grecian lore!

Another, fam'd from far New Zealand's shore!

A third, whose recent death we all bewail,

Justice dispens'd with an impartial Scale!

And for thy Daughters--Sandwell (if it could)

Would till one lives but only to do good!

And one, who closes such a noble Line,

At Cambridge adds a grace to Learning's sacred Shrine!What man then, happy Shade, but envies Thee,

With such Descendants, such Posterity!

These the best Monuments!--more sure to live,

Than any that the Sculptor's art can give.

The one indeed may have their little day,

But from the first they hasten to decay.

While thine, more durable than brass or stone,

Shall last as long as England's self is known!Holmrook Terrace,

Tunbridge Wells.

GEORGE AUGUSTUS, FIRST BISHOP OF NEW ZEALAND, 1841, BISHOP OF LICHFIELD, 1867, BORN APRIL 5th, 1809. DIED APRIL 11th, 1878.

[35] II. I give now some details of my second brother's early life and of his private and domestic characteristics, which were afterwards more fully developed in his public exertions for the good of others. And I begin with my dear mother's portrait of him in his childhood. He was born April 5th, 1809, and my mother writes in 1813, when he was four years old--

"Little George finished 1st Vol. of Cobwebs. He began French, 1814."

"Jan. 1st, 1817. George Augustus (not 8 till April) has learnt the Latin Accidence perfectly, reads very well, and knows much of the Bible: is very forward in Geography-, and writes and cyphers very well. He is very kind to his little brothers and sister."

I may add this kindness showed itself in his readiness to repair any damage done to the children's [35/36] favourite toys. "I'll detrive it," he used to say, when wheels were broken from carts, and his mechanical skill in the manufacture of little carriages and other playthings delighted the younger ones.

He early evinced a strong desire to become a sailor, purchasing with the first money he possessed, Anson's Voyages, but this wish he yielded in obedience to the strong disapprobation my parents felt of his purpose, though he retained through life a love for sea-faring adventures, and used often to say when in New Zealand, obliged to go long voyages, that the two lives he preferred were now both enjoyed by him. Among my mother's records I find the following passage, "Dear George has improved very much in steady conduct, and his attentions to his younger brothers have been truly delightful to me. His desire and intention to take Holy Orders appear to be accompanied by a suitable reverence for sacred duties, and his amiable and affectionate attention to his mother are truly gratifying."

These affectionate attentions were never relaxed. My mother, in her declining years, being affected by [36/37] mental depression, arising from pressure on the brain, found in her son George her chief comfort. He often spent whole days in soothing her wayward fancies, entering into her often delusive projects, which he managed to persuade her to abandon, without appearing to oppose her wishes. Though she cordially approved of his decision to leave England as Bishop of New Zealand, she never recovered his loss, but died on the anniversary of his consecration (Oct. 17th, 1842), from a sudden attack of apoplexy, while in the act of prayer--a most blessed end to a life of devotion to her children.

I resume my mother's record of his youthful days, "March 25th, 1833. George was elected a Foundation Fellow of St. John's College." "June 9th. Dear George Augustus was ordained Deacon, at St. George's, Hanover Square, by the Bishop of Carlisle, his father and I were present. He read prayers at Kew in the afternoon, and his brother (the Prebendary of Ely) preached: present--their father, mother, (Julia, wife of the Prebendary), Letitia, Frances Elizabeth, Thomas Kynaston, and Charles Jasper.

[38] June 16. The two brothers officiated at the new Chapel (St. John's, Richmond), all the party attending both morning and afternoon, except their father who stayed at home in consequence of a cough."

I may here add that from the time of his admission into St. John's College, Cambridge, dear George was never any expense to his father, He quickly obtained a College Scholarship, and on his leaving the University, became Tutor to the sons of the Earl of Powys, having also (as before stated) obtained a Fellowship. He also undertook, at the request of Mr. Bagster, the task of correcting for the press the editions of the Old Testament (in Hebrew) and of the New Testament in Greek, forming part of the Polyglot edition, published by Mr. Bagster.

He was always anxious to assist in our endeavours to improve the character of my father's tenants. When I undertook the charge of a district, consisting of about fifty houses, all on my father's property, he gave me much sound advice, and books to use in my school. One Bible I treasure to this day. In [38/39] our early days, Richmond was only a hamlet to Kingston, and had no resident clergymen till the Hon. and Rev. Gerald Noel was appointed by the Vicar, the Rev. S. Gandy. The Sunday Services were conducted by two clergymen who had schools in Richmond, and the parishioners were contributors to the fund by which their services were remunerated.

There being already so many particulars published of the Bishop's Life, both in New Zealand and at Lichfield, I confine myself to his life at home. During one of his visits to Richmond, before his appointment to New Zealand, and while he was engaged as Curate at Eton he gave us a most interesting account of his work among the soldiers quartered at Windsor, whom he assisted in preparing for Confirmation. He divided them into classes, some could not read at all, others knew only the Creed and the Lord's Prayer, others could read but very imperfectly. He mentioned a remark made by Lord Seaton on the readiness with which soldiers received instruction, which he attributed to their habits of obedience, which led them to accept the [39/40] directions given them on religious subjects. In consequence of the statements made by several officers at Windsor, as to the unsatisfactory performance of Divine Service, my brother used his influence to promote the building of what is now called the Military Church, where all the regiments now attend in succession with comfort and regularity.

My mother often recalled this visit, saying she never saw her dear son to such great advantage, nor felt so strongly what a power he had of influencing others. I shall never forget his expressive countenance and animated description of his military pupils, gathered in the parish Church for examination. He always took a great interest in soldiers, wherever he was brought into communication with them, and they in their turn greatly acknowledged his exertions for their benefit.

Several stained-glass windows were given by some of the regiments he had taught in New Zealand, for his private Chapel attached to the Palace at Lichfield.

In site of his multifarious engagements, my [40/41] dear brother never failed to write long and interesting letters to his father, giving an account of his missionary voyages, and of the islands he visited. These were always carefully copied by my father and preserved for many years. Many of them have since been published in his life.

My father never recovered from the agitation he experienced when the Bishop returned to England in 1854, and when he had determined to sail in a vessel built for him, which proved unseaworthy. His return was delayed in consequence, and he was finally persuaded to take his passage in a larger vessel, leaving the Southern Cross to follow with her crew, in order to relieve my father's anxiety. But the repeated leave-takings, and other excitements attending the Bishop's departure, March 25th, 1855, so told on my dear father's constitution that he only survived till July 25th of that year, having had a paralytic seizure during the previous winter.

Not only was my brother anxious to save his father the expense of his education at College, but he exercised the greatest self-denial in his personal [41/42] expenditure. I have often heard him say, when asked why he never smoked, that the weekly cost of but one cigar a day would amount to no inconsiderable sum, and if, as was customary, friends were invited to share in the indulgence, a still larger amount would be required, which would seriously diminish his income. His wonderful activity enabled him to perform on foot what to others would appear very long and fatiguing journies, and this was one of his modes of economy--often attended with great personal inconvenience.

I remember his making one of these pedestrian tours to visit his eldest brother at Branstone, and not being able to obtain accurate information as to the locality, he continued on till night overtook him without his having found a resting place. Nothing daunted by the difficulty, and as in those days there still existed the stocks, often used as a punishment, he quietly lay down to sleep on the bench in the market place of a village not far from Branstone, then he rose early, made his ablutions by the help of the adjacent pump, and proceeded on his way, having [42/43] at last obtained the right information as to Branstone. A neighbouring clergyman hearing of this adventure observed, when he was told of his appointment to the Bishopric of New Zealand--"Surely he was the very man for the post," which at that time involved much courage and self-denial.

On one occasion my brother and Mr. Tyrrell (afterwards Bishop of Newcastle in Australia) and a Mr. Martin, walked from Cambridge to London, during a night of heavy rain, arriving in a deplorable state at a stand of hackney coaches (then the only available conveyances) and found a difficulty in persuading the drivers to take them to their different destinations. This certainly did not prove an economical journey, as their clothes were hopelessly injured. My brother usually slept with a window open, even when snow fell and penetrated his room, which having a northern aspect was often liable to cold blasts. He always thought it wise to inure himself to exposure to weather, ever having in view future trials in his missionary labours. His feats of rowing and swimming are still recorded at Eton, and when in [43/44] New Zealand he visited stations in the Middle Island he delighted the rough men by his ready participation in their labour. One said--"Ah, sir, he'll sit down and eat whatever we have, and then he is such a rare hand in the boats."

The perfect unselfishness of the Bishop's character was evinced not only in his public life, but in his family circle and daily habits.

When only a boy of fourteen, my brother George often volunteered to accompany me in rides which I might not have enjoyed but for his kind escort, as I had no servant, but the loan of a pony from a friend for several weeks. He used to dismount to gather blackberries for me, and, to prevent my feeling over-tired he rode so near me that I could rest my right arm on his left, and so enjoy a long ramble through lanes now no longer existing. The station at Willesden, and other buildings have long since covered them, and transformed them into a busy thoroughfare. Sixty years ago this part of the country was most enjoyable, from the pleasant, shady, almost unfrequented roads, bordered with hedges in which wild flowers abounded.

[45] I have known him so entirely occupied in caring for and attending to his guests as scarcely to take any food himself when receiving large gatherings for any diocesan meeting.

On one occasion, just before his appointment to the Bishopric of Lichfield, we were staying with his son at a country vicarage where no man servant was kept. I heard a voice outside my door early, and concluding that it was my nephew; begged him to come in. It proved, however, to be his father, who said--"I knew you would not be able to fasten up your travelling bath, so I am come to do it."Trifling as those details may seem, they show the character of the man, whose minute attention to "little things" was conspicuous in every-day life. I have never seen his equal in this thoughtful care for the comfort of others. After his appointment to Lichfield, he felt the need of a house in London, not only for himself, but for those of his friends who were obliged to attend Convocation, or other public meetings, and as the late beloved Primate offered him the use of the then ruinous Lollard's Tower, he, [45/46] together with his elder brother, undertook the needful repairs and furnishing of this ancient and historical edifice.

The cost exceeded their calculations, and they lived but a short time to enjoy the use of it; but during their stay it was the scene of many social gatherings. I can speak gracefully of the comfort I enjoyed in being allowed to remain there for many weeks, that I might have the best medical advice, and above all, the soothing society of himself and his dear wife. I was also after a severe illness, in 1872, received at the palace, Lichfield, for three months, till able to return to my work.

On the occasion of my dear brother's consecration in Lambeth Palace, Oct. 17th, 1841, the Archbishop (Howley) invited my father and elder brother to partake of a very sumptuous repast after the ceremony. The newly appointed Bishop could not forbear to remonstrate against this luxurious banquet, saying that when Paul and Barnabas were sent out by the Apostles, as we read in Acts xiii. 3, they laid their hands on them with fasting and prayer. [46/47] These elaborate entertainments have never since been given, and instead of the private consecrations of Colonial Bishops, they have usually been solemnly performed in some great metropolitan church, or in Westminster Abbey, in the presence of vast congregations.

I had the great pleasure of first receiving my dear brother on his arrival in England in 1867. It happened to be the time of the Triennial Musical Festival at Birmingham, and as I was then living at Sandwell Hall, the seat of Lord Dartmouth, superintending an Institution founded by Lady Dartmouth, he wrote to tell me he would be with me on the last Wednesday in August, in order to be present at the performance of the Messiah on Thursday. On Friday he also attended the performance of Israel in Egypt, and I accompanied him. I remember a clergymen, then Vicar of West Bromwich, who recognised my brother from his likeness to a photograph, and introduced himself to him in order to assist him in finding my room in Birmingham, where he rested after the Oratorio was over, telling [47/48] me afterwards, that he felt, if the Bishop had then asked him to return with him to New Zealand, he should have assented without the slightest hesitation, so powerful was the influence of his countenance and manner.

I am aware that this brief sketch is far from conveying any idea of my beloved brother's excellencies, but as I find it is intended to publish a more detailed account of his life, by the Rev. Canon Curteis, who enjoyed for many years the privilege of almost daily intercourse with him, I the less regret my own inability to do him full justice. In fact the deep affection I felt for him made me always distrust my powers of delineating his character, and owing to his engagements and my own frequent illness, our intercourse was often much interrupted.

[49] APPENDIX TO CHAPTER II.

____Extract from a letter of the late Bishop of New Zealand, to his son, September 30th, 1862.

____"But one piece of advice I will give, and that is,--not to underrate or neglect the appointed course of study for the College or University Examinations. The subjection of the will to a course of reading, which you do not choose for yourself, is far more profitable than a larger amount of actual knowledge acquired by following your own inclinations. The most valuable branch of education is the discipline of the will. If I had understood this, when I was an undergraduate, I should have worked at mathematics simply because I disliked them. The greatest part of life after all is the hewing of wood and drawing of water, doing what must be done, without any question, whether we like it or not; and the sooner a man comes to that conclusion, the better for his own peace of mind."

[50] III. I begin now the momorial of my third brother Thomas Kynaston Selwyn, whose short but remarkable life has never been recorded. My mother thus writes of him, "January, 1817.--Thomas Kynaston (not five till March) can read without spelling at all, spells words of three syllables, knows the multiplication table, and the catechism all but the Sacraments: has advanced as far as the "Questions concerning English History," in "The Mother's Catechism of useful things to be known," is particularly fond of geography, and knows all the rivers and capitals in England and in Europe, and a great deal of the other quarters. He put together the dissected map of England and Europe at three years old; knows a great many Hymns, and learns one, by choice, at a time, instead of one verse, which [50/51] would be thought sufficient for such a child. He has such a reverence for Sunday, that when his father, on a Saturday, gave him a new book of maps which delighted him beyond measure, he put it under his pillow that night, and did not take it out in the morning, because, as his mother observed when she went into the nursery, it was Sunday, and she felt persuaded it was for this reason alone, before she had said anything on the subject, the book had not been removed from the pillow."

I find no record of his career at Eton: but after his admission into Trinity College, Cambridge, he obtained several college Prizes, viz.,

In 1831, the 1st Verse Prize, and the 1st Class Prize.

In 1832, 1st Class, and 1st Verse Prizes.

In 1833, The 1st Reading Prize.

In February, 1833, he was elected Craven Scholar.

On July 2nd, 1833, (to quote my mother again)--"Dear William (his father) and I heard T. Kynaston recite his Prize Greek Ode in the Senate House at Cambridge." The subject of the Ode was Thermopylae.

[52] In 1834, dear T. Kynaston proceeded with a party of six pupils (including his youngest brother, Charles Jasper) to a cottage at Abergele, called Pensarn. Here he was attacked by illness, and proceeded on July 5th to Chester to consult a physician. His brother, Charles (who was with him) left him resting on a bed at the Feather's Hotel, and, on his return, found that he had breathed his last. The shock was great to all; but his disease had been of long standing. From a child he had suffered from what was called the wind dropsy, a distressing form of flatulence, which so distended the abdomen, that, as Dr. Thackeray and the Richmond doctor had predicted, it occasioned pressure on the heart, and thus caused his death.

A tablet is erected to his memory in the Antechapel of Trinity College, Cambridge.

The following letter from his brother George is published in the life of Bishop Tyrrell and will be read with much interest:--

"My dear Tyrrell,--Pray accept my heartfelt thanks for your most kind and Christian letter, [52/53] which I found here on my arrival. It is needless to say that I feel to the full the truth of the consolation contained in it; and I hope that I have been enabled to apply it. I have never lost a near relation before. When I first received the intelligence I was surprised that I was not more affected--I began to think that there must be some lack of storge, some morbid apathy in my heart, which prevented me from mourning. But I was soon comforted by finding that this was not the case, for I would rather sorrow every day, than be too hard-hearted to sorrow at all. I found the pause of insensibility was only the delay of the heart in learning what it never knew before,--the nature and qualities of grief. The lesson was one of bitterness; but it was quickly and effectually learnt. And I felt how salutary it was in its operation, and how truly it may be said, that sorrow brings us nearer unto God.

When I saw you in the coach, I did not know that you knew all that had happened, and could have told me more than I then knew myself. You might have stopped my journey, but I am glad that [53/54] you did not; as I have had a melancholy satisfaction in visiting my brother's last abode on earth, and the place where he sleeps in death. I find now that my brother Charles wrote word that the funeral was to take place on Tuesday the 8th, and that he himself should return to London as soon as possible. I went to Wales under the impression that my brother had died at Abergele, and was still unburied; whereas he had been buried several hours before I heard of his death. I actually met my brother Charles between Woburn and Lathbury. The mails stopped side by side to exchange coachmen; we were both outside, and yet never recognized one another. I went on to Chester, stopped at the very Inn at which my brother died (The Feathers), with my name on my carpet-bag and on the way-bill, and yet nobody told me a word about the real state of the case, At Chester, I met my father's clerk, who had left London a day before me, but having gone by way of Birmingham, had been detained on the road. We started together for Abergele at 8 p.m. on Wednesday, and arrived at 1 a.m., and with [54/55] great difficulty awakened the people of the Inn, and inquired for Pensarn, my brother's cottage. It was about a mile from the Inn, and close to the seaside. The way led through the churchyard in which I thought that my brother's grave must then be open. We called up a woman at a farmhouse, and were directed to the cottage. Though it stood within a hundred yards of the sea we could not even at that time of the night catch the sound of the smallest ripple. After some waiting, we roused the maidservant, and inquired for my brother. She could scarcely speak English, and all we could collect was that my brother left the house on the Thursday before. Here was a new difficulty, for at that time I had no other idea than that my brother had died at Abergele. At last she made us understand that W. Richardson was still in the village. To his lodging she guided us; and to my relief we saw a light in the window; for though it was now 2 a.m. they were still sitting up in compliance with the odious Cambridge custom. From him I learnt all the particulars of my brother's departure and that [55/56] he had been buried the previous day. I returned, grieved and disappointed, to my sofa at the Inn, for the bedrooms were all occupied.

At 6 a.m. I rose, and went to the cottage, where I found everything lying as if its former occupant had been still there. All his books, most of which had once been mine, were in the rooms; the manuscript note books which he had made at my suggestion, but with far greater industry than I could attain; every object was familiar to me, and therefore everything excited painful recollections.

When my melancholy task was accomplished, I returned to Chester, and heard from the physician, Dr. Thackeray, all the particulars of my brother's last illness. No one seems to have anticipated so speedy a termination of his sufferings. On the morning of Friday I went to the Cathedral, and had scarcely entered the aisle before I was struck with a fresh inscription,--I went to the spot, and found as I expected: "Thomas Kynaston Selwyn, Scholar of Trinity College, Cambridge, died July 5th, 1834, aged XXII."

[57] I thought of the lines in Moultree's beautiful poem in the Etonian:--

"One hurried glance I downward gave,

My foot was on my brother's grave."While standing on the spot, I became sensible that Service was being performed, and went to the door of the choir to listen: at last I fancied that I caught the words--"We commend to Thy Fatherly goodness all those who are in any ways afflicted."

I say fancied, because as it was Friday morning this prayer is not usually read; but, perhaps at Chester the Litany is a separate service; you may well suppose that my heart and voice responded Amen, both for myself and my parents.

At 8 a.m. I left Chester by the mail, and after holding converse with John Bunyan almost all the way to London, arrived at Richmond at 9 a.m. on Saturday. You will be glad to hear that I found my family much more resigned and tranquil than I had expected.

Charles (his brother) has been the greatest sufferer, but he also has felt the force of those consolations, [57/58] which you have truly called the greatest of all. Pray give my kind regards to your sister, and believe me your very affectionate friend,--G. A. Selwyn."

* * * * * * The loss of this beloved and gifted son, was a great trial to his parents, but the conviction that from his peculiar disposition and extreme simplicity of character, he was wholly unfitted to cope with the trials of life, gradually lessened their sorrow. He was so incapable of suspecting anyone of deceit or fraud, that he would have become a prey to any designing person, who took advantage of his confiding reliance on any promises or suggestions. His extraordinary gift of memory was accompanied by a deficiency of comprehension, thus realizing the assertion of the poet,--

"Thus in the soul while memory prevails,

The solid power of understanding fails."--Pope.Though he never attended a races meeting, he took great interest in the winners of every celebrated contest, and could repeat their names from the very first establishment of the stakes. He was a frequent [58/59] contributor to the Sporting Magazine, often sending very striking descriptions, in verse, of the more remarkable events of the turf. I cannot now refer to one of these correctly, as I have not a copy of the magazine: but it must have been published between 1820-1830, as the verses record the success of a horse of George the 4th at Goodwood races, ridden by the once-famous jockey, Robinson.

After describing the excitement caused by the race, he writes,--

"Whose is that steed? and whose that crimson vest?

'Tis he 'tis he, 'tis Robinson confessed!"* * * * "Why from the crowd ascends that deaf'ning cheer,

Why bursts the music on the listening ear?"* * * * * (then follows a description of the King, and of the striking up of "God save the King," when the horse won)--

"To him their loud applause his people pay,

For him that Anthem's silver accents pray--

[60] Let other Monarchs soar and triumphs grace,

Thine be the peaceful honours of the Race."

During his stay at Eton occurred the famous contest respecting the Boats, the use of which was at that time prohibited, and the masters resolved to punish all who were guilty of transgressing their edict. The boys who belonged to the boats, in order to evade their authority, dressed up several of the waterside boatmen (called cads) in their own caps and jerseys, and sent them in a procession to row, while the masters, on horseback, followed the supposed delinquents, threatening expulsion, and other punishments. On the return of the boats to the Brocas, the masters confronted the rowers in order to identify them, but the men quickly disclosed themselves as "only cads," and thus the threatened disgrace was diverted from the supposed culprits. Thomas K. Selwyn wrote, in Homeric verse, a description of this exciting scene,--a portion only of it has been preserved. It was never printed, but [60/61] his father long retained it, and it may still be recovered, if, after reading these memorials, any surviving friend may be able either to produce a copy of it, or to give information as to its present possessor.

The result of this mortifying defeat of the masters, was the legalisation of the boat races, the only restriction being made, at the suggestion of the second brother, George, (afterwards Bishop of New Zealand) that no one should be allowed to go in a boat till he had passed an examination in swimming and men were placed at certain stations to instruct them in swimming, each station being more dangerous than the preceding ones, and after a certificate from the last station, the boys were allowed to possess boats, and to use them at regularly appointed hours. The result of these judicious arrangements has been that no case of fatal accident has occurred at Eton since the plan was established.

My dear brother's love of geography and topography was evinced by the anecdote I here insert from the recollections of friends.--He went to see [61/62] the Aduor [corrected to Adur in the text] fall into the sea near Shoreham, tasting the waters to discover which was the river and which the sea, which gave occasion to the following Sonnet, written by his eldest brother, Professor Selwyn:--

"Had'st thou been with us Brother; how thine heart

Would have delighted in this mountain stream,

For thou while here on earth, did'st nothing deem

So lovely as the Rivers: on the chart

Thine eye would track their windings, and apart

From all companions oft'times wouldn't thou go

Where the bright waters into Ocean flow,

And taste, if salt or fresh. But where thou art

What tongue can tell thy pleasures pure and bright,

What heart would wish thee still to linger here?

Hope whispers, near the fount of love and light,

Thou drinkest of God's River, crystal clear;

And thou hast learnt how peaceful and how free

The Spirit mingles with Eternity."

SIR CHARLES JASPER SELWYN, LORD JUSTICE, BORN OCTOBER 13th, 1813. DIED AUGUST 11th, 1869.

[63] IV. The career of the youngest of the four brothers, though differing in many respects from that of the elder ones, partly owing to his secular employment and partly to the prominent position he was required to take in the management of his father's affairs, when the parent was by age and infirmity obliged to delegate much to others, was yet characterised by the same high principle, persevering industry, and general kindness of disposition, as was that of his elder brothers. I here give his mother's account of his early years:--

"January 1817.--Charles Jasper, three last October, (having been born October 13th, 1813) says the Lord's Prayer very well and everything suitable to his age; can repeat three of the Commandments and Watts' Scripture names. Is remarkably lively and good tampered." I may add to this that in all his life, which extended to the age of 56, [63/64] he was remarkable for his unvarying good temper and calmness whenever inclined to give way to excitement or anger. His mother adds, "An account of a conversation which took place at Eton will in few words give a portrait of Charles."--Mr. and Mrs. Delafosse invited him to dine with them (in 1826, when aged 13) and on Mrs. D. saying to him "I fear there is a great deal of vice (wickedness) here among the boys," he answered--"I dare say there is, or, I dare say there may be;" "but," he added, putting his hands on his side in a manly attitude, "You need not do wrong unless you like it." The four brothers were all together for one term at Eton, Charles being sent rather earlier than the others, and the eldest, William, remaining till July, 1824.

Charles obtained several prizes when admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1832. He chose English authors as his prizes, viz.:--

Burke's Works in 1833--15 vols.

Spencer [changed to Spenser in text] in 1834--8 vols.

Shakespeare in 1835--8 vols.[65] After leaving Cambridge in 1836, he commenced studying for his intended profession as a Chancery barrister, and became a pupil of Mr. John Tyrrell, an eminent conveyancer, the eldest brother of Bishop Tyrrell, the life-long friend of his brother George. Their friendship has been mentioned in the memorials of T. K. Selwyn.

Under Mr. Tyrrell's instruction he made rapid progress, and as soon as he was called to the Bar, his success was remarkable for so young a man. He continued to reside at Richmond, assisting his father in the management of the family estate, and also in the publication of the last two editions of the Abridgement of the Law of Nisi Prius.

In 1867, he obtained the office of Solicitor General, which he held till the following year, when after the death of Lord Justice Rolt, he was appointed Lord Justice in conjunction with Sir William Page Wood, afterwards Lord Hatherley. This office he only retained a year, being a great sufferer from an internal complaint, for which he consulted Sir Henry Thompson, and by his advice underwent several [65/66] painful operations-but alas! without success, as on August 11th, 1869, he sunk under the exhaustive and internal inflammation, at the comparatively early age of 56.

The following is his eldest brother's affecting account of the last sad days of his life:--

"Richmond, August 10th, Tuesday.--Sad tidings of our dear, good brother. This day week all seemed to be going well. They had got to Richmond on the Saturday before, to his great joy. No more letters for five days, Rosalie saying there was nothing to tell from day to day; but on Sunday morning the 8th, Dr. Hassall was very anxious, but Charles hopes that no one will come to see him now. No immediate danger; all he can do is to see his doctor, and now and then a few minutes on business with Mr. Bagot. This determined me to come up on Tuesday to see R. at all events, and Dr. H. Then, before I started, a telegram--"Charles is worse." I got here at 5 p.m. and found him drinking a little sip of champagne "And that's the last," he said. He was very pleased to see me, and smiled very sweetly! "Oh! I am [66/67] so glad to see you, you look very well--how is Julia, &c.," and then dropped into a doze, as he does continuously. Up to Sunday he took his meals well, but on Monday, sickness, loss of appetite and constant hiccups, and the bad symptoms of disordered interior increasing--so sad! but he is so patient and thankful. GANZ and Johnny came at 11.30 p.m. very tired. He gave us all a blessing. Feeling sure he would not live till Wednesday, G., A., and I prayed for him, and now and then with him. Sir H. Thompson's assistant came about 12 o'clock, and stayed an hour. No hope. GANZ fast asleep in S. Room. Poor Charley asleep in N. room. Rosalie and I were with him all night, but I made her go once to rest. Dr. H. too here all night, relieving him from time to time; frequent pain and groans, but so patient. He said, "I hope we shall all meet in His Heavenly kingdom--I die in the faith of the Resurrection of the dead, through Jesus Christ." About 4 o'clock his pulse was so low and breathing so oppressed, I prayed the last prayer for him, and R. said, "Did you hear love?" Yes! [67/68] I heard every precious word and hope the prayer will be granted." At 5 o'clock I called GANZ, and we asked him whether he thought he could receive the Holy Communion. "Yes! I hope all imperfections will be forgiven." Little Charley had come down to be kissed again before this. Then came dear GANZ, W', Johnny, his two sons, Rosalie, Dr. Hassall, the butler, kitchen maid, the gardener, the nurse; he said Amen to the prayer and we were all comforted. Eight a.m. Still lying in short dozes, now and then he has said, "the time is long, but the end is not far." In chamber--his doctor, nurse and servants, and sent love to all, to Fanny--I wrote to her lately. I said to him once--

"Vitâ frater amabilior,"

"We've always been like brothers, William." It seems there is some organic disorder besides the sad disturbance caused by the operations, for which there is no healing in man's art.

8.50, departed in peace, all of us with him--cannot write more. Kind love to both. Your affectionate Brother,--W. S."

[69] The loss to his family by the death of Lord Justice Selwyn was incalculable. He had always acted as legal adviser of his elder brothers, as trustee for many other relations, and was actively engaged in the management of the family estate.

To the parish he was always a zealous and conscientious supporter of all measures designed for its prosperity. He gave the sites of two additional churches, St. Matthias's and Holy Trinity, and also aided the first Vicar, Rev. H. Dupuis, in his efforts to restore the Parish Church. He was a regular attendant at the Vestry whenever disengaged, and often gave up other business when any important measure was under discussion, in order to attend its meetings. Though compelled by his professional duties to reside in London, he took every available opportunity of exercising hospitality in his ancestral home--receiving large parties of friends for social gatherings, cricket matches and other amusements. He often received young men, employed in London all the week, for rest and change from Saturday to Monday in summer. He annually gave a boat to [69/70] be rowed for, and always promoted every scheme for the benefit of the watermen, being himself, like his brothers, an enthusiastic lover of the oar, and skilful in all aquatic achievements. His earnest wish was that the family home should be kept up for the use of any of the members who might need it. The house was left to his widow till his son should attain the age of twenty-five years, but her death in 1875, unfortunately defeated his intentions, and the trustees were induced to let the house for three years, during which it suffered much from the neglect of the tenant, who afterwards died a bankrupt, leaving part of the rent and all the dilapidations unsettled. Sir Charles's second wife, the widow of Rev. H. Dupuis, having again married in 187 l, all the children, except the youngest son, born after his father's death, were removed to Lichfield, to be under the care of his brother the Bishop. On the death of the Bishop in 1878, the house was vacated, and the eldest son and his sisters, together with myself, again took possession of it, but only for a time, as a disastrous fire occurred in 1881, and the eldest sister having married [70/71] in the December of that year, it was again advertised to be let, and a sale took place in June, 1882, of the furniture. But it is to be hoped that it may yet again be inhabited by the family who for more than seventy years have been established there.

There is no doubt that the railway and the consequent increase of population have greatly destroyed the once celebrated beauty of the place. In 1817, when the father of the four brothers took possession of the house, on the death of his father, Richmond was quite an aristocratic place of residence. The road to the Hill was through fields and gardens, and shadowed by fine trees. Opposite the house lived the Earl of Shaftesbury; by the river stood the mansion once occupied by the Duke of Queensberry; the houses of Mrs. Osbaldeston, Miss Fanshawe, Lady Anne Bingham, &c.; and on the Hill the Dowager Countess of Mansfield, Lady Morshead, and Sir Lionel Darell had their residences. All is now changed: the Marquis of Lansdowne's beautiful seat converted into a Brewery; Lord Pembroke's house on the Green destroyed, and on its site villas erected; [71/72] hence the distaste evinced by the youthful members of the family for a place now become a suburb of London. But there is still the river, the matchless view from the Hill, the beautiful and extensive Park, and last, not least, the now perfectly appointed Kew Gardens, filled with the choicest trees and shrubs, and the hothouses teeming with rare plants from every part of the globe. To the old inhabitants, who remember the days when the ruinous and ill-arranged houses contained scarcely more than the collection brought by Sir Joseph Banks from the Southern Pacific, when admission was only given once in the week, and it required a considerable outlay even to reach the gardens,--the present state of things is indeed a refreshing contrast.

It may here be mentioned that a large part of the gardens formerly belonged to the Selwyn Estate, but was exchanged by our father for land belonging to the Crown near the Hill. This transfer was recognised in a courteous letter, written by order of Queen Charlotte in 1817, and accompanying the gift of a private key to my mother, of which constant use [72/73] was made, for entrance into the gardens, when closed to the public. These particulars are given, as of late the right of the Selwyn family to a private key has been disputed, though in the Museum in Kew Gardens hangs a map of the estate, in which is included, what is therein called "The Selwyn Property."

These Memorials will, it is hoped, stimulate the junior members of the family--Sir Charles's two sons, and others, to re-establish the family home, and to endeavour to imitate the self-denial, industry, and perseverance of their progenitors--even if not gifted with those superior talents by which the four brothers here commemorated, were endowed.

The death of Sir Charles Selwyn, while his children were too young to act upon his wishes and principles, and their subsequent removal to Lichfield, where they remained seven years under the care of their uncle, the Bishop, severed their connection with Richmond, and of course weakened their attachment to the home of their fathers. It had been the wish of Sir Charles that his son (who was to inherit the [73/74] estate) should be brought up at Richmond, and gradually initiated into the management of the property, but this having been prevented by the letting of the house, he decided on entering the army, and obtained a commission in the Royal Horse Guards Blue. This stop necessitated his accompanying the regiment wherever it was stationed, and he also in 1882 volunteered and was accepted for service in Egypt. There he suffered from sunstroke, and was compelled to return on the sick list.

Thus his absence from Richmond was protracted, and on the marriage of his eldest sister with Mr. E. Fraser Tytler, of Aldourie, Inverness, and her consequent removal to Scotland, he decided to break up the home, which had been re-established in 1878 on the death of the Bishop of Lichfield, and in 1882 it was again let for several years. It is still to be hoped that at the expiration of the lease, if not sooner, he may again become an occasional, if not permanent resident of the family mansion. His presence would be most beneficial, and if he resumed his position as a Vestryman he might promote many [74/75] undertakings for the benefit of the parish.

His property has increased in value since the opening of the different railways to Richmond, and the vast number of houses built and occupied in consequence of the facility with which London is now reached.

One great object remains to be accomplished--the building of a Church for the accommodation of the inhabitants of many hundreds of houses, recently erected on the Selwyn property on the Kew Road, formerly covered with market gardens. This undertaking needs the active influence of the landlord, as the enlargement of the old church on Kew Green, only suffices for the needs of the inhabitants of Kew and its immediate locality.

Should any profit arise from the sale of this little Memoir, it will be devoted to the interest of the Building Fund. At present the only Church accommodation is supplied by a small Iron Church, originally built by Rev. Canon Hales, to afford religious instruction to the people inhabiting Sandy Lane. It was at first used as a school, but licensed [75/76] for Divine Service on Sundays. It has since been enlarged, but it is far from sufficient for the overflowing congregations who attend it.