'I arose in the night, I and some few men with me; neither told I any man what my God had put in my heart to do at Jerusalem.' 'And I went out by night, and viewed the walls of Jerusalem which were broken down.' 'Then said I, Come and let us build up the walls of Jerusalem, that we be no more a reproach.' . 'So built we the wall.' 'We made our prayer unto God.' 'We laboured on the work.' 'And so the wall was finished.'--Nehemiah, ii. [(1) The First Lesson for S. Augustine's Day according to the Old Lectionary.]

'What I want you to notice as new, since Christianity began to act on society, as unprecedented, as characteristic, is the power of recovery which appears in society in the Christian centuries.'--DEAN CHURCH's Gifts of Civilization, p. 202.

WITH the publication of this remarkable letter we enter on the fourth, the present period in the history of S. Augustine's. According to all reasonable calculation, according to all laws of probability, it was bound to pass away and be no more seen. But in the providence of God this was otherwise ordered; and if [38/39] the story of the origin and glory of the Abbey, and of its decay and desolation, is striking, still more so is the story of its restoration.

To whom is the restoration due? It is due to three men, each remarkable in his way, each distinguished for the good work he has done for the Church of his birth.

The first is the writer of the letter just quoted. The second is the late Right Hon. A. J. B. Beresford Hope, then Member for Maidstone. Born on the 25th of January, 1820, he was educated at Harrow, where he obtained a scholarship and prizes, and thence proceeded to Trinity College, Cambridge. Here he gained in 1840 the English and Latin Declamation prizes, and in 1841 obtained the Member's prize for a Latin essay. [(1) He took his M.A. in 1844; Hon. LL.D., 1864; Hon. D.C.L. of Oxford, 1848; Hon. LL.D. of Dublin, 1881; Hon. LL.D. of Washington and Lee University, and the University of South Tennessee, U.S.A.] In the library of the famous mansion, which his father built at Deepdene, in Surrey, the author of Coningsby wrote that famous novel; and it might have been expected that the son would have devoted himself solely to the parliamentary career for which he was so eminently adapted, and the patronage of art for which he became afterwards so famous. But already he had shown traces of the influence of [39/40] the religious revival which had begun to affect the English Church. At Kilndown, near Bedgebury Park, which came to him through his mother, the wife of Marshal Beresford, the church was a meagre, barn-like building. This, when only eighteen years of age, [(1) MS. letter from the present Vicar of Kilndown, the Rev. H. Harrison.] he changed into one worthy, so far as human hands could make it, of a House of God, erecting in it a new altar, and filling it throughout with painted windows.

The letter of Robert Brett fell under his eye in the autumn of 1843, and, as he himself said on one occasion, 'Much as I was struck with the letter, it is very possible that it might have run off like a drop of water, had it not been for a strange and providential accident. I had engaged myself to pay my first visit to Canterbury the very week after that letter had appeared describing the terrible condition of the ruins. The visit was paid. Archdeacon Lyall showed me over the Cathedral, and when I said I should like to see the ruins of S. Augustine's, of which I had read, he answered, "If you want to see them, I will take you. But you will be very much disappointed. They are miserable things. They are not worth a visit"' However, he went. He saw the noble gateway, the brewery vat, the ragged and disreputable [40/41] public-house, the tangled garden and skittle-ground, the grotto-like recesses of ancient date called 'cloisters,' the high pieces of wall painted black for target practice, the ruined foundation of Æthelbert's Romanesque tower. [(1) A. B. H. in the Archæologia Cantiana, vol. iv.] He saw and made up his mind, keeping his intention, like a wise man, to himself. He returned to London and directed his lawyer to negotiate for the purchase of the ruins, of which he was eventually allowed to become the purchaser at a somewhat reduced rate of payment, as it was believed the unknown buyer was seeking the building to promote the brewers' legitimate trade. [(2) 'He showed me the gateway, and the beerhouse which stood on the site of this hall. I said, "Thank you," and kept my intentions to myself. When I got to town I drove off to my lawyer and said, "Mr. Walker, some old premises at Canterbury are for sale, and I mean to buy them." My lawyer sent some one to the sale, and they were bought; the sellers being in the comfortable belief that they would be kept in the orthodox trade.'--Speech of Mr. Beresford Hope in the College Hall, S. Peter's Day, 1883.] But before he completed the purchase he had to get three private Acts of Parliament passed, and at length the site was actually made over to him.

But now there is a third and quite as remarkable a man to come upon the scene.

This was the Rev. Edward Coleridge, younger son of Colonel James Coleridge, of Heath Court, [41/42] Ottery S. Mary, in the county of Devon. He was considerably older than Mr. Beresford Hope, having been born on May 11, 1800. He was educated at Eton, where Dr. Pusey and Dr. Jelf were in the same form with him. He took his degree as a Member of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, in 1822, and was afterwards elected Fellow of Exeter. In 1824 he was appointed an assistant master in his old school, being the first instance of an Oxford man nominated to a mastership at Eton. [(1) Amongst Edward Coleridge's pupils were the younger Hallam, Archdeacon Balston, Lord Justice Cotton, Goldwin Smith, Bishop Patteson, Sir Stafford Northcote, Sir George Rickards, Lord Chief Justice Coleridge, and Dean Goulburn.] He was assistant master at Eton from 1824 to 1850, and lower master from that date till 1857, when he became Fellow of Eton, and Vicar of Mapledurham. As lower master he marvellously improved that part of the school, raising its numbers eight or ten fold, [(2) See next paragraph] and might have been [42/43] known to the world only by his success in the scholastic profession, famous for his zeal, his energy, his power of sympathy, and 'an absolute transparency of character which never pretended to know more than he really did know.' But in the providence of God other influences were brought to bear upon him. Amongst these are to be placed that of his sister, Lady Patteson; of Mr. Justice Patteson, a sound Churchman of the old school, thoroughly devout and scrupulous in observance, ruling his family and his household on a principle felt throughout; of the late Bishop Selwyn, whom he styles 'my most dear of all dear friends;' and finally of Bishop Broughton, who became in 1836 the first Bishop of Sydney. Through these, and especially the last-named Bishop, his whole soul was filled with the idea of doing all in his power for the spread of the Colonial Church. Not only did he assemble at his own house at Eton the forty guests who greeted the newly-consecrated Bishop Selwyn; not only did he accompany him, before he sailed, from Eton to Exeter and from Exeter to Plymouth; not only did he watch for and pick up the last pebble on which the Bishop set his foot before going on board the ship, as the last reminiscence of that 'friend of friends,' and then stand a long while watching on the Hoe as the ship spread her sails and glided away in the [43/44] distance, but he set himself with characteristic energy to supply Bishop Broughton's longing for a Missionary Training College in England.

[Footnote (2) from above: With the help of Chapman and Wilder he substituted as a lesson on Sunday mornings the Greek Testament for Virgil or Juvenal. See Maxwell Lyte's Eton College, p. 370: 'No one who does not recollect the traditions of the School in the first quarter of the century can believe the weight of the earthly mass that Atlas had to bear; and if James Chapman was the Atlas, Edward Coleridge was the Hercules, and so "Hercule supposito sidera fulcit Atlas." I often used to think in later days of J. H. Newman's sermon on S. Peter and S. Andrew, and compare Chapman to the latter and Edward Coleridge to the former.'--C. J. A., in the Guardian, May 30, 1883]

At a time when missionary zeal was rare, and rarest of all in our public schools, he seemed to be consumed by it as with a fire. In the midst of the harassing duties of a Master at Eton, with a house full of pupils, and with the additional cares of church work at Windsor for which he had volunteered, he devoted himself with untiring energy to his design. 'Tenax propositi,' he went straight on with his project, and suffered neither frequent discouragements, nor manifold misconceptions, nor adverse insinuations, to divert him from his purpose. Circular followed circular, all written in his own hand. The first, a private one, to elicit the opinions of competent persons; a second addressed to personal friends asking for promises of help; a third, laying his views before the Masters of Colleges at the Universities and the Heads of Public Schools, suggesting that they should not only aid him with donations, but fit scholars for training. Replies poured in from all quarters. From the Bishops, who in various degrees expressed their warm approval of his design; from Whewell, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge; from Tait, then Head Master of Rugby; from William Wordsworth, the Poet Laureate; from [44/45] Keble; from Lonsdale, the Principal of King's College, London; from Pinder of Wells, and many others; and before long he had obtained a numerously signed list of ample donations and promises of help. 'Instant in season and out of season,' he stirred, roused, in some cases shamed, men into sharing some portion of his own enthusiasm. Liberal as he was himself in giving, even to a fault, he did not shrink from laying his demands on all sorts and conditions of men with fearless importunity. [(1) See next paragraph] Whenever he knew a man he pressed his plans upon him. Whenever he heard of a man and did not know him, but thought him likely to be helpful, he introduced himself to him.

[Footnote (1) from above: ' I can contribute,' writes Bishop Hobhouse, 'one anecdote lately brought to my memory by a friend who witnessed the fact in Parker's bookshop, Oxford. "Mr. Parker, you will send me this set of books," pointing to a row; "Mr. Hobhouse wishes to give them to," I forget what, "Diocesan Library." Mr. H., though standing by, had been quite unconsulted. This will show how freely he commanded contributions from the young Eton men whom he had influenced.' 'I remember the way,' said Sir Stafford Northcote, 'in which he sent us round his first prospectus, with his printed papers enclosed in an envelope, on the leaf of which were inserted some such words as these, "If you value the spiritual interests of the Colonies and love Edward Coleridge, co-operate." I remember one of my friends saying, "Well, I do not know that I care much about the spiritual condition of the Colonies" (it was a shocking thing to say, and he must have been rather a reprobate), "but I do love Edward Coleridge."'--Speech at S. Augustine's, S. Peter's Day, 1883.]

Hitherto he had been working in the dark. [45/46] Communications and inquiries were set on foot respecting Oxford, Salisbury, and Southwell. One proposed one place, and another another. At length there came tidings of the purchase of the ruins of the Abbey of S. Augustine by Mr. Beresford Hope. Instantly Edward Coleridge saw his opportunity. [(1) 'His elements of success were the combination of a clear idea of what he wanted; consistency, not to say obstinacy, and unwearying energy in following it out. The machinery which worked this was admirable. A singularly handsome and attractive presence; a fine voice; a great versatility of transition from the gravest to the most playful and simple ready eloquence; and added to this much shrewdness and discernment of character.'--Mr. Beresford Hope, in MS. letter.] He was fired by the associations of the place. He lost not a moment. 'He made my acquaintance,' says Mr. Beresford Hope, 'by seeking me out, and when I got the site he wrote and asked me if I meant it for him. I answered fairly that I could not tell. I held out hopes, but could not say positively whether the site was adapted for the purpose, or whether a Missionary College was the best destination for it. A few months' reflection, however, convinced me that it was so. Thenceforward the two undertakings became united, and then the vague scheme of devoting the site to the needs of a Missionary College became the grand one of restoring the old house of S. Peter, S. Paul, and [46/47] S. Augustine, to the same missionary objects for which it was first founded.' [(1) From the speech of Mr. Beresford Hope on the day of the consecration of the chapel. See Twenty-five Years, p. 31.]

The joy of Edward Coleridge was unbounded at seeing his idea taking shape in a way he never could have anticipated. He wrote at once to Bishop Broughton in Australia, and the Bishop in reply writes: 'I had no sleep last night for thinking of the news, and you will find some reason for thinking that I dream of it by day. Indeed I hope it makes me thankful as well as thoughtful.' On the second day of his Easter vacation, 1845, Edward Coleridge spent a morning in surveying the excavations made by Mr. Hope. This brought on a severe attack of erysipelas in the head, which, to use his own words, 'deprived him for a full week of the use of mind, sight, and body.' But nothing damped his ardour. Returning to Eton he was soon at his familiar labours. 'I see him now,' writes one who was under him in these days, 'opening his letters at the breakfast-table, with their heavy cheques and promises of help, having ordinarily enough to astonish us boys.' He allowed nothing to impede his energy or weaken his determination. Unmoved by the sinister sneers and opposition of those whom he describes 'as clean gone mad in [47/48] affirming everything sinful and untrue which the Church of England holds in common with that of Rome,' he laboured on in conjunction with his friend Mr. Hope. While Newman was despairing, the two were planning, consulting, holding interviews with Archbishop Howley, and watching with eager interest the carrying out of the designs of the eminent architect, Mr. Butterfield, for the erection of a building which should be, to use the words of the venerable Bishop of Fredericton, 'no motley collection of ill-assorted plagiarisms but a positive creation, a real thing which may be said to be like nothing else, and yet like everything else, in Christian art.'As month followed month the fabric gradually rose, with the Chapel, the Hall, the house for the Warden, the Fellows' buildings, and the rooms for the students. It was thought they could be accommodated in their new home in 1846. Then Whitsuntide, 1847, was named. But the solidity of the buildings, and the furnishing and laying on of water, coupled with the extreme severity and length of the winter of that year, rendered delay necessary. 'I always endeavour,' writes Edward Coleridge, 'as far as my ardent, hopeful, go-ahead temperament will allow me, to remember that consolatory saying of good Mr. Bowdler to me, when complaining somewhat of one who checked me [48/49] in the outset about the College, "Ah, my dear friend, you cannot conceive how great a privilege it is to wait."' At length Thursday, the feast of S. Peter, 1848, was definitely fixed upon, with a close regard to the appropriateness of the day for this revival of the old religious house of S. Peter, S. Paul, and S. Augustine.

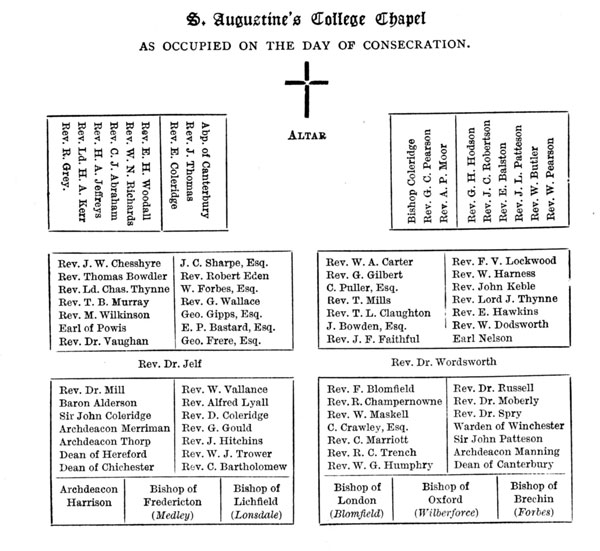

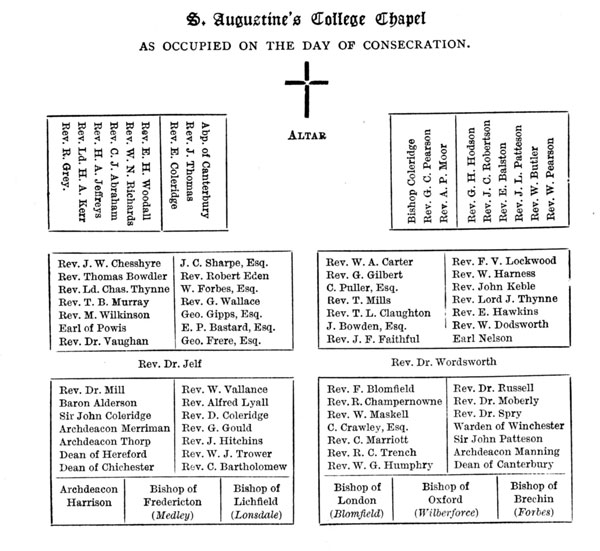

The previous Sunday had witnessed the furious outbreak of the revolution at Paris and the murder of Archbishop Affre. A peaceful contrast was the scene in which our own Archbishop Sumner [(1) Archbishop Howley died February 2, 1848.] now took a prominent part. Canterbury was crowded on the Wednesday evening, and there was great difficulty in getting beds at any price, although the principal parties concerned in the ceremonial did not arrive till Thursday morning. A special train, which left London at five a.m., [(2) The Queen's concert having been unluckily fixed for the 29th of June, the Archbishop himself proposed the early train on the 29th.] brought the Archbishop, Mr. Beresford Hope, and many friends to Canterbury. At eight o'clock those who had been invited assembled in the dining-hall, and the Chapel bell was rung by one [(3) The Lady Mildred Beresford Hope, sister of the present Premier, the Marquis of Salisbury.] who was born on the 24th October, 1822, the [49/50] very day that the act of vandalism described above brought the majestic ruins of S. Æthelbert's Tower with a crash to the ground, and who, as the wife of Mr. Beresford Hope, by her 'devotion, wisdom, toilsomeness, charity, and courage, was her husband's right hand in carrying on his great work.' [(1) Speech of Mr. Beresford Hope on S. Peter's Day,1883.] About nine o'clock the procession entered the chapel in the following order:--

The service of consecration then commenced, and before the day was over the great design of Beresford Hope and Edward Coleridge had been accomplished. During the morning there was much and continued [50/51] rain, but whilst the Holy Eucharist was celebrated, the sun broke forth, lighting up the Chapel with its rays, falling in bright gladness on the crowd of devoted worshippers kneeling on the bare pavement [(1) Mr. Beresford Hope himself knelt by the side of Mr. Henry Tritton.] in the centre of the Chapel. [(2) See next paragraph] About noon there was service at the Cathedral, where the Archbishop preached the consecration sermon, choosing for his text Eph. iii, 10, 'To the intent that now unto the principalities and powers in heavenly places might be known by the Church the manifold wisdom of God.' At three o'clock upwards of twelve hundred guests sat down to luncheon in the Museum and Cloisters of the College, and throngs of visitors roamed over the quadrangle and inspected the various buildings, while many repaired to Evensong at the Cathedral. Thus this memorable day came to an end, and the Chapel of the Missionary College of S. Augustine, itself the Guesten Chapel of the old house, restored and lengthened, had been rededicated to the worship of God, and the ancient monastery had been made ready to do once more 'its first works.'

[Footnote (2) above: The offertory in the Chapel itself amounted to 508l. 9s. 10d.; the collection at the Cathedral to 429l 13s. 10s., making with 50l. sent in on the following day a total of 988l. 3s. 8d. The following plan of [51n/52n] S. Augustine's College Chapel, as occupied on the day of Consecration, gives a list of those present: