THE HOLY MASS

MAN was made for the worship of God, and in this, the highest expression of his powers, can come to the fulness of his being. Worship is not merely one among the many activities of life, from which man can turn to other things unrelated to it; it is the formal act by which man renders to God the account of the whole of his life, and itself affects the whole quality of man’s living.

Under the most diverse conditions, man has found in sacrifice the most complete method of worship. Even in the darkness of the heathen world, and in the misguided and sometimes cruel expression of his desire to worship, he has been groping towards something that is true and holy. The Old Testament remains as a constant reminder to us that the principle of sacrifice was taken up into the ancient dispensation for God’s chosen people, and was purified for them of much of its grossness.

It is in terms of sacrifice that the meaning of the life, death and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ was interpreted in some of the most penetrating of the passages of the New Testament; and the idea of sacrifice not only lies behind much that is in the Gospels, but was present in the mind of Christ himself. The whole meaning and purpose of all ancient sacrifices was gathered together in one point, when, by his death on the Cross, the Saviour of the world offered himself in a sacrifice of perfect obedience.

The strands that were gathered together at Calvary have from that point radiated again over the whole world. The prophecy of Malachi, “From the rising of the sun unto the going down of the same” (that is to say, from the farthest east to the farthest west) “my name shall be great among the Gentiles; and in every place incense shall be offered unto my name, and a pure offering” (i. 11), has been fulfilled in a way beyond any that the prophet could have imagined, through the act of our blessed Lord. On the night before he died, at the Last Supper, he gave to his disciples a means by which they, and all those who should be of their company to the end of time, could have their part in his oblation.

To the kind of worship with which they had been familiar in the synagogue, the first Christians therefore added the new Christian rite, “the breaking of bread.” The developed rite of the Mass as we have it to-day does no more than add to the essential elements of our worship the natural growth of forms of prayer and traditional gesture and action. In studying the eucharistic rite in its developed form, we shall have constantly to look back through the ages to notice how the Church, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, came to express itself in the liturgical forms with which we are now familiar.

There were of course more ways than one of enshrining the principles of the eucharistic act in liturgy; and in the east of Europe those who hold the same faith that we hold have many different customs in worship. The Church as a whole is enriched by this variety. Our present concern is with the western tradition of worship, which is not less beautiful than others in its inherent austerity.

Unto the altar of God

THE HOLY MASS

O sacred Banquet,

in which Christ is received,

the memory of his Passion renewed,

the mind filled with grace,

and a pledge of future glory given unto us.

PREPARATION

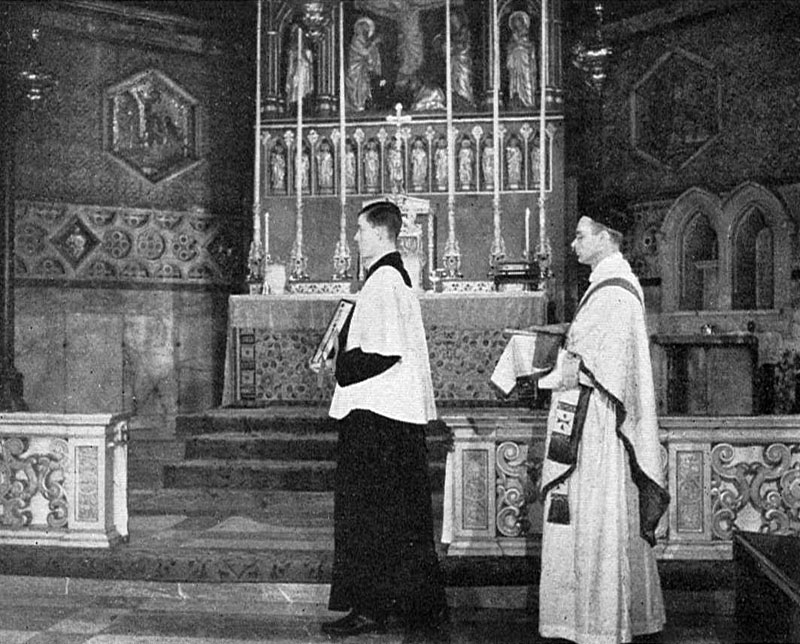

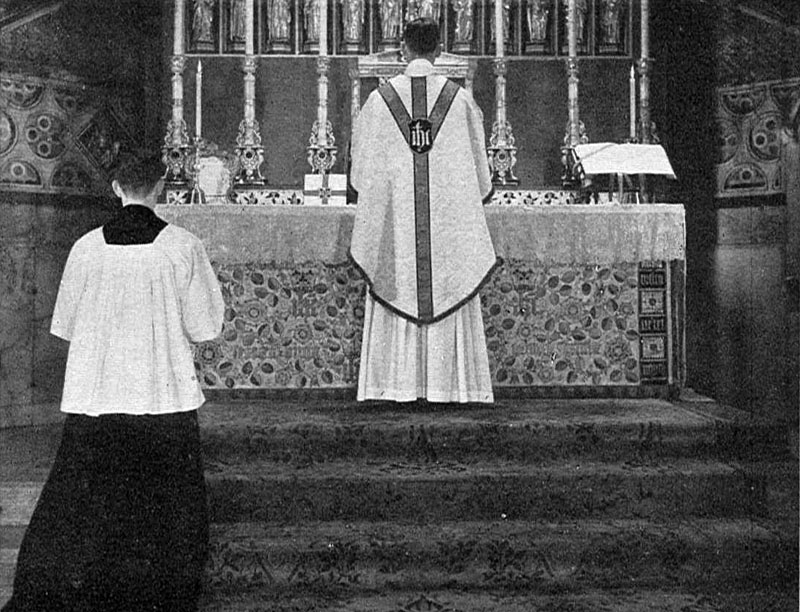

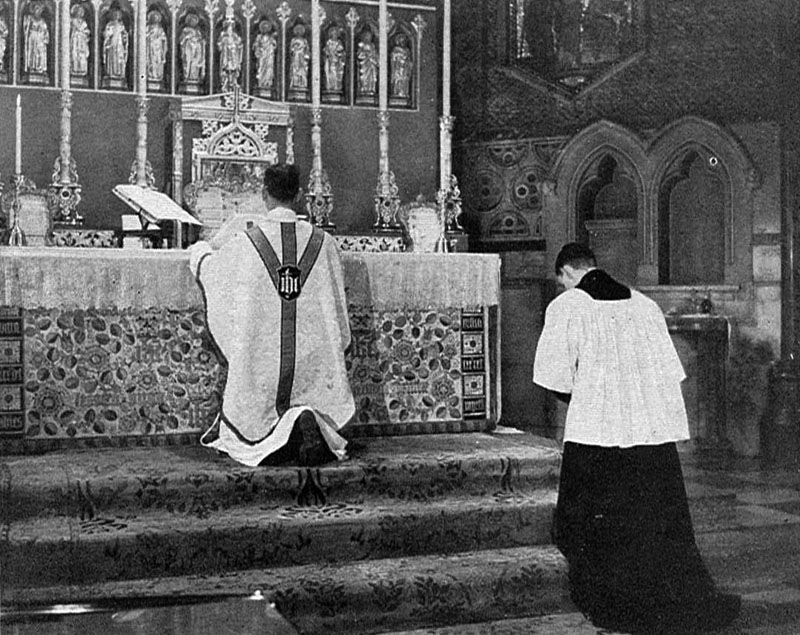

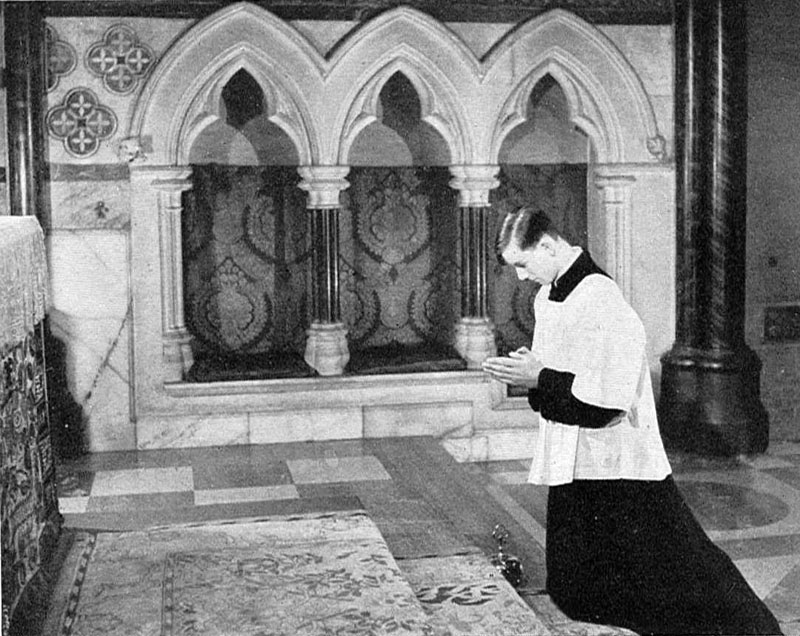

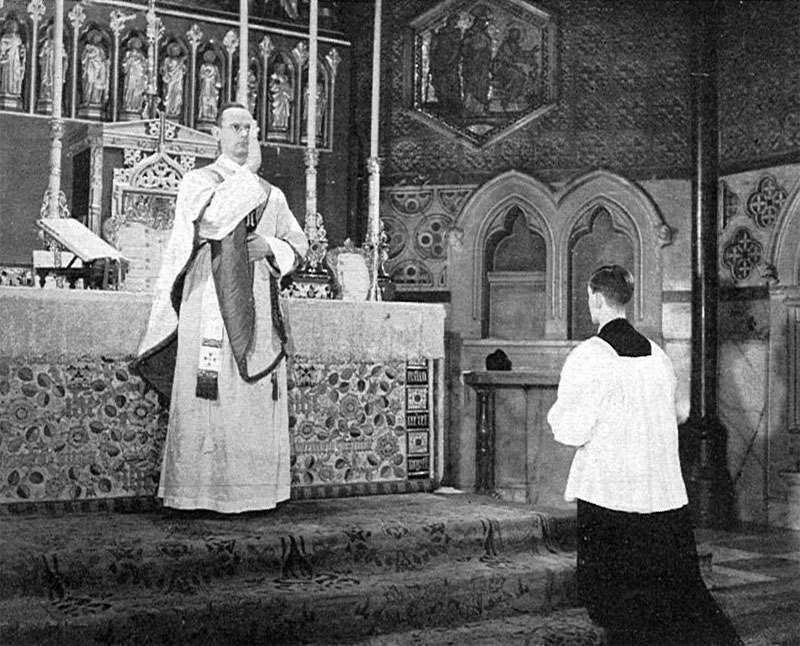

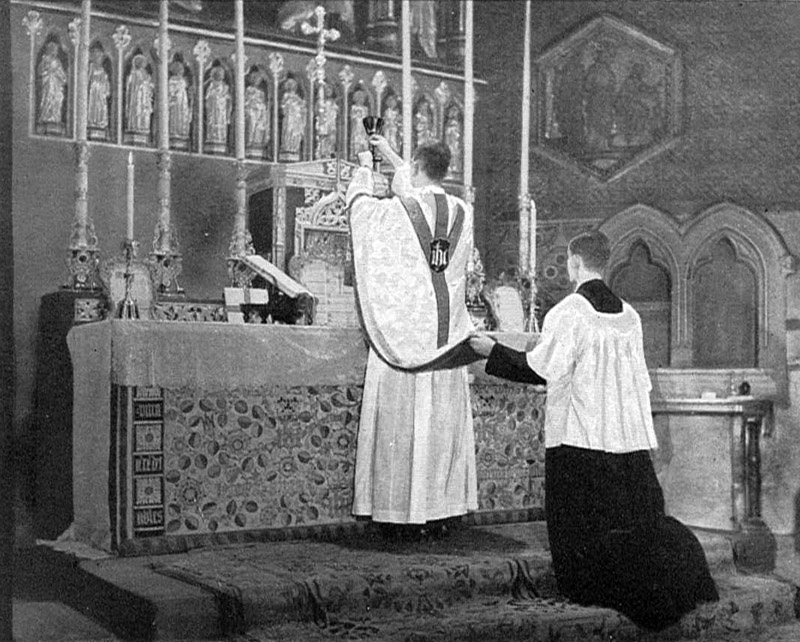

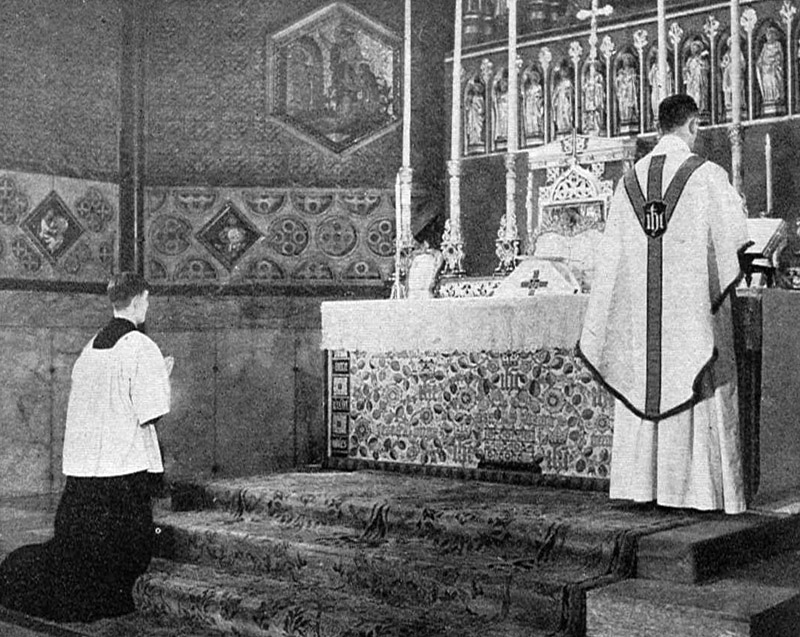

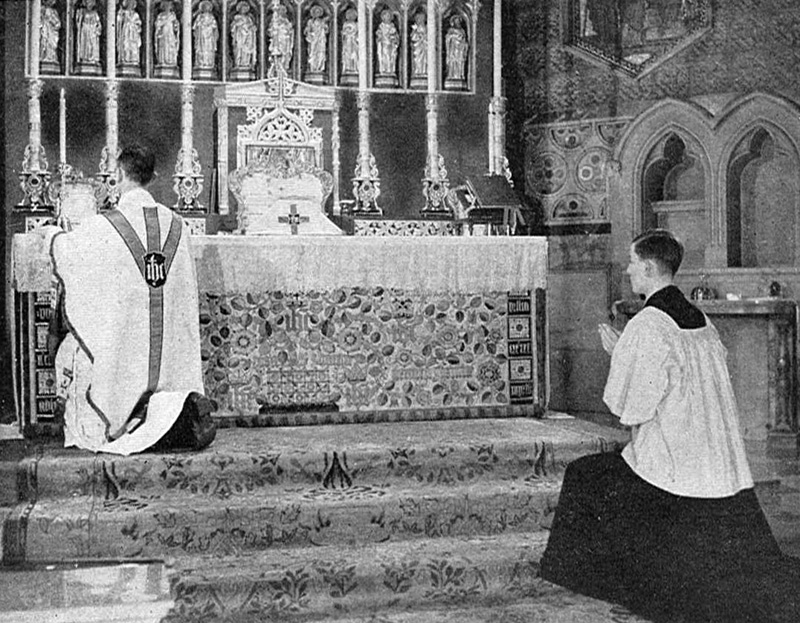

THE main action of the Liturgy begins with the Introit, a chant which the priest reads at the altar, and which the choir at High Mass sings at the very beginning of the service. Before reading the Introit (and at High Mass while the choir is singing it), the priest stands at the foot of the altar, with the server kneeling near him, for preparatory prayers. They consist of the Forty-third Psalm, a confession of sin, some versicles and responses, and two prayers on approaching the altar.

The custom of using such preparatory prayers arose comparatively late in the history of the Church, during the Middle Ages. They were a natural development, providing the priest with suitable devotions to occupy his time during the singing of the Introit, in which he had no part. In England we know that St Thomas of Canterbury made use, during such pauses in the action of the rite, of devotions compiled by his predecessor St Anselm. As the celebrant became accustomed to prefixing prayers to the more ancient part of the rite, they were used even at Low Mass, when there was no singing, and became an accepted element in the service.

There is wise advice in the Book of Ecclesiasticus: “Before thou prayest prepare thyself, and be not as one that tempteth the Lord” (xviii. 23). It is a salutary custom to prepare ourselves for the greatest of all acts of prayer, the offering of the holy Sacrifice. The themes of penitence and expectation which are to be found in the preparatory prayers of the Mass should be the themes of all our preparation for drawing near to God our Maker.

In the name of the Father

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

V. I will go unto the altar of God.

R. Even unto the God of my joy and gladness.

Psalm 43

V. Give sentence with me, O God, and defend my cause against the ungodly people: O deliver me from the deceitful and wicked man.

R. For thou art the God of my strength, why hast thou put me from thee: and why go I so heavily, while the enemy oppresseth me?

V. O send out thy light and thy truth, that they may lead me: and bring me unto thy holy hill, and to thy dwelling.

R. And that I may go unto the altar of God, even unto the God of my joy and gladness: and upon the harp will I give thanks unto thee, O God, my God.

V. Why art thou so heavy, O my soul: and why art thou so disquieted within me?

R. O put thy trust in God: for I will yet give him thanks, which is the help of my countenance, and my God.

V. Glory be to the Father.

R. As it was.

V. I will go unto the altar of God.

R. Even unto the God of my joy and gladness.

V. Our help is in the name of the Lord.

R. Who hath made heaven and earth.

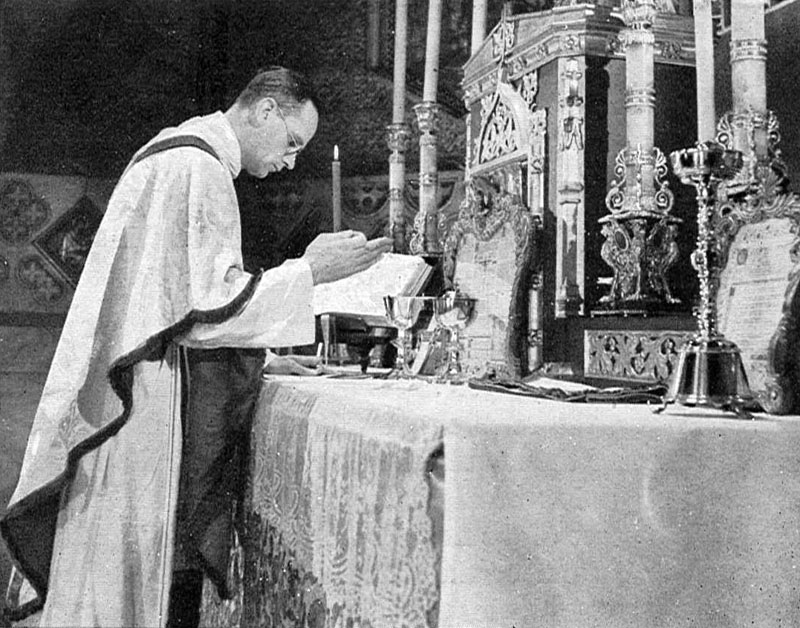

THE PSALM OF EXPECTATION

The altar having been prepared beforehand, the priest spreads on it the white linen cloth on which the Blessed Sacrament is to rest. This is called the “corporal” (from corpus, body). The priest sets the chalice and paten upon it, and descends to the foot of the altar for the preparatory prayers. He wears the traditional vestments that link our worship with that of early ages; for we are not now concerned with the personality of the individual priest, but with that sacred office of priesthood which is the same in all ages and places. As the minister of God, the priest therefore enters upon his sacred task by making the sign of the cross, and invoking the aid of the Holy Trinity.

After the invocation, the priest says the versicle (taken from the psalm that follows) “I will go unto the altar of God,” and then recites, alternately with the server, the song in which the Jews of old expressed their longing for worship at God’s altar. In the sorrows of the world, they prayed God to lead them to the holy hill of Sion, to the temple that stood there as God’s dwelling, and to the altar of sacrifice. Their longing was a foreshadowing of that of God’s new Israel, and is fulfilled in the joy of Christians as they come to the altar of a greater and more perfect Sacrifice. As at other times, the Christian significance of the old words is accentuated by the addition of the Gloria Patri to the psalm; for in our worship we are entering into the never-ending worship of God Father and Son and Holy Ghost.

The message of the psalm, that we should approach God with trust and confidence, is repeated in the following versicle, when, again making the sign of the cross, the priest affirms that “our help is in the name of the Lord.”

Through my fault

CONFITEOR

I confess to almighty God, to blessed Mary ever Virgin, to blessed Michael the Archangel, to blessed John Baptist, to the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, to all the Saints, and to you, brethren, that I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word, and deed, through my fault, through my own fault, through my own most grievous fault: Therefore I beg blessed Mary ever Virgin, blessed Michael the Archangel, blessed John Baptist, the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, all the Saints, and you, brethren, to pray to the Lord our God for me.

R. Almighty God have mercy upon thee, forgive thee thy sins, and bring thee to everlasting life. The priest says: Amen.

The server says the Confession, changing you, brethren to thee, father.

V. Almighty God have mercy upon you, forgive you your sins, and bring you to everlasting life. R. Amen.

V. The almighty and merciful Lord grant us pardon, absolution, and remission of our sins. R. Amen.

THE CONFESSION OF SIN

Our approach to God’s altar must be made with trust in his availing mercy, and with penitence for our own sins. Having recalled the mercy of God, the priest bows down with humility to make a general confession of sin. He acknowledges before God the all-holy, against whom our sins are so grievous an offence, that he has sinned against him in thought, word and deed, and thrice beats his breast in penitence as he admits that it is through his own fault that he has sinned. As also our offences are against the whole Church of God, the priest also makes this confession before the Blessed in heaven (remembering especially the sinless Mother of God; St Michael, the leader of the holy Angels in their warfare against Satan; St John Baptist, the great preacher of repentance, himself sanctified “even from his mother’s womb”; St Peter, who “wept bitterly” in sorrow after denying his Lord; and St Paul, who was converted after being a persecutor of the Church); and before his brethren in the Church on earth. He prays for pardon from God, and asks the prayers of the Church in heaven and on earth. In the name of the people, the server says a prayer for pardon on his behalf.

Then in his turn, still speaking for the people, the server makes the same Confession, to which the priest replies with the same prayer. At the Absolution which follows, both priest and server make the sign of the cross, since it is through the power of the Cross alone that our sins can be forgiven.

In assisting at Mass, we should seek to join in these acts of penitence, with prayer for the priest who ministers on our behalf, and with a real sorrow for our own sins.

Shew us thy mercy, O Lord

V. Wilt thou not turn again and quicken us, O God?

R. That thy people may rejoice in thee.

V. Shew us thy mercy, O Lord.

R. And grant us thy salvation.

V. Lord, hear my prayer.

R. And let my cry come unto thee.

V. The Lord be with you.

R. And with thy spirit.

Let us pray.

Our Father ...

Almighty God, unto whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid: cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy name; through Christ our Lord. R. Amen.

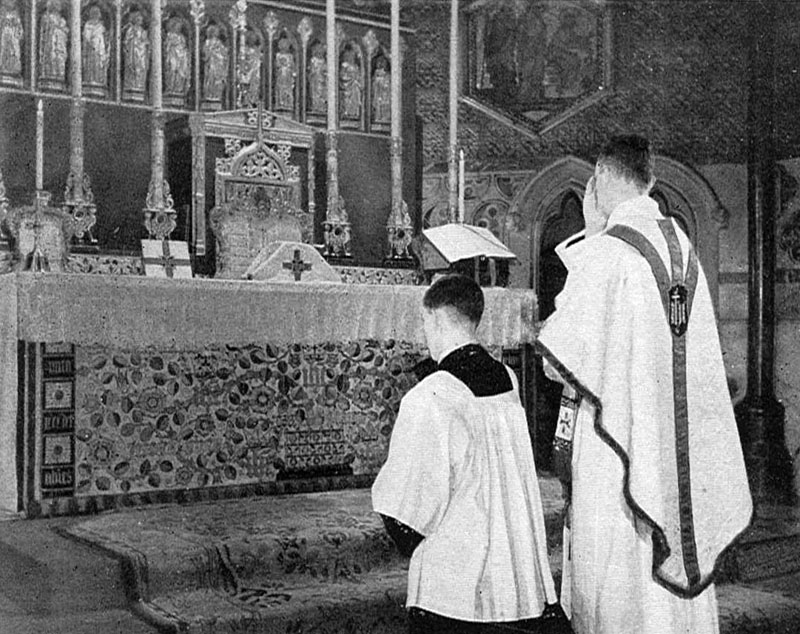

THE APPROACH TO THE ALTAR

After the Confession, the priest bows moderately while he says a series of “versicles” (that is, short verses), to which the server makes the “responses.” The first two are taken from Psalm 85. With renewed trust in God’s goodness, the priest prays that we may obtain mercy and salvation, and that our prayers may be acceptable to God. Then he adds the Lord’s Prayer and a special prayer for purity, beseeching God, who knows the inmost secrets of our hearts, to cleanse our souls from all iniquity and make us worthily to join in worshipping him.

These two prayers were the only ones of the act of preparation which were retained in the Prayer-Book when the Mass was put into English in 1549; the others have more recently been restored to use, as they were originally intended, to meet the needs of Christian devotion. Since the Lord’s Prayer occurs later as a proper part of the eucharistic rite, it would be out of place here, were not the act of preparation which includes it a separate section of the whole service, and apart from the main action of the Mass.

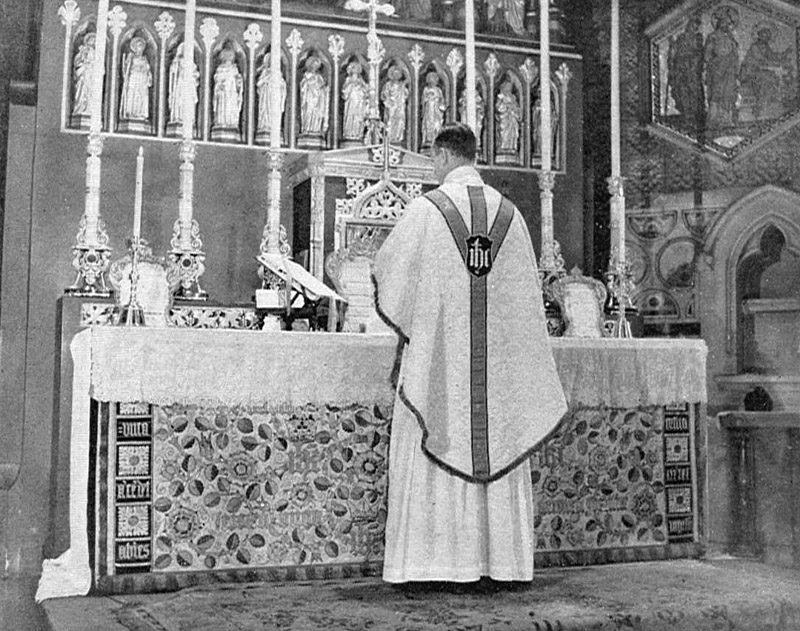

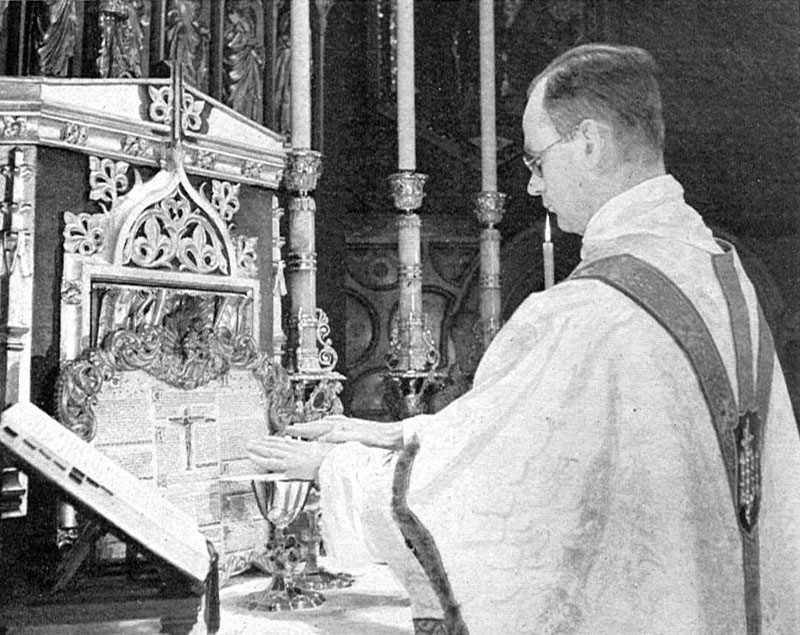

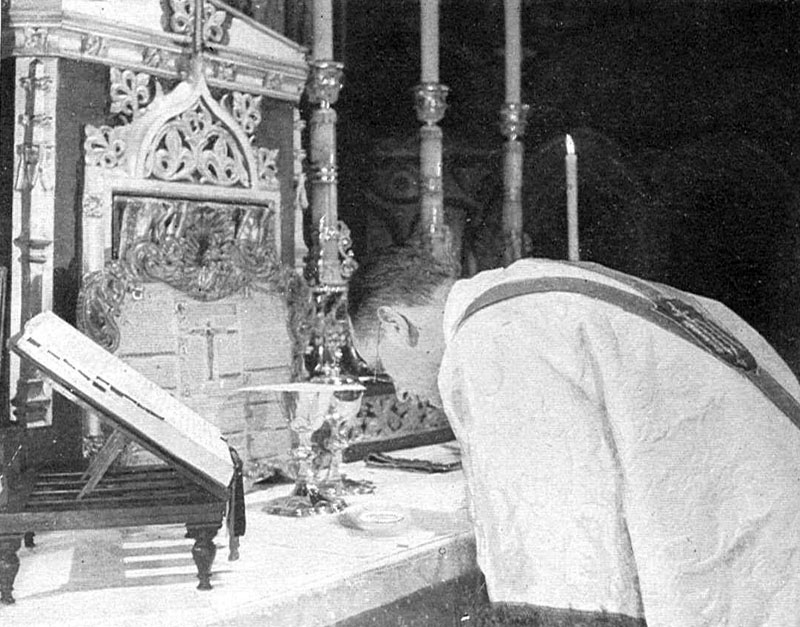

So ends the preparatory part of the service; having asked for God’s guidance, besought his pardon, and prayed for purity of heart, priest and people are now to begin the supreme act of Christian worship. The prologue is over; the great drama of Catholic worship is about to begin. The priest reaches the altar, which he kisses in the middle as a sign of reverence, and passes to the side, where the missal (the book containing the words of the service) lies open for him to begin.

THE GATHERING OF THE CHRISTIAN PEOPLE

The Mass (excluding the “prologue” of preparation and the “epilogue” of dismissal) falls into two main parts. By their old Greek names the former was known as the “synaxis” or “meeting,” and the latter as the “eucharist” or “thanksgiving.” They are of different origin, the one corresponding to the Jewish worship of the synagogue, of which it is a development; and the other to the sacrificial worship of the Temple, of which it is a fulfilment. The “synaxis” consists of prayer and instruction; the latter part of the service contains the strictly eucharistic action. To the “synaxis” the words of the Holy Scriptures are central; to the “eucharist” the Bread and Wine on the altar. The former is subject to many variations, with proper prayers and lessons for particular days; the latter is substantially unchanged from day to day.

The normal conjunction of the two parts of the service nevertheless has come down from as long ago as the second century, when it provided the ordinary Sunday worship of the Catholic Church. We may well see in it the result of the guidance of the Holy Spirit. The Christian needs to worship God with his mind as well as with his heart and will, and the earlier part of the service contains both the means to impress on him the truth of God, in readings from the Holy Bible, and for his own expression of that truth in prayer, praise and creed. The meaning to us of the eucharistic action that follows is enriched by the understanding of the word of God that comes from the earlier part.

Christian devotion is most fruitfully nourished by the words of the Holy Scriptures, by biblical prayers and praises such as the Psalms, by the words of the Gospels, and by the teaching of prophets and apostles. Our loss is great if we neglect these sources of the devotion of the Church through the ages, from some of which (especially the Psalms) our Lord derived the words of his own prayers.

Glad in him with psalms

THE INTROIT

The Introit is the entrance-chant, sung by the choir at High Mass, the priest saying the preparatory prayers meanwhile. After ascending to the altar, the celebrant himself reads it, making the sign of the cross at the beginning. It consists of a Psalm-verse with “Glory be to the Father,” preceded and followed by an antiphon, and varies with the feast or occasion.

When the Spanish pilgrim Etheria visited the Holy Land at the end of the fourth century, she found the custom of singing during the entrance of the bishop had replaced the informal entrance of earlier days. The custom, perhaps introduced by St Cyril of Jerusalem, seems to have reached Rome in the early fifth century.

The varying words of the Introit serve to sound a key-note for the devotion of the day; they represent a use of the Psalter more ancient than its continuous recitation in the daily Office, which was begun by the early monks.

Have mercy

KYRIE ELEISON

Kyrie, eleison. Or, Lord, have mercy. (3 times.)

Christe, eleison. Christ, have mercy. (3 times.)

Kyrie, eleison. Lord, have mercy. (3 times.)

The ninefold prayer, still commonly said in the Greek tongue, has replaced the ancient litany that until the time of St Gregory (d. 604) was said at this place. It consists of three petitions addressed to each Person of the Holy Trinity.

The ninefold Kyrie eleison was first introduced on ordinary days when the litany was not to be used, but soon began to replace it on feast days also. The Greeks themselves, from whom the prayer came, neither limited the number of petitions to nine, nor used a special form to address our Lord; and these features may be due to St Gregory.

In some churches the Gloria in Excelsis follows here, according to ancient custom. It will be found in this book on page 89.

The Lord be with you

THE SALUTATION

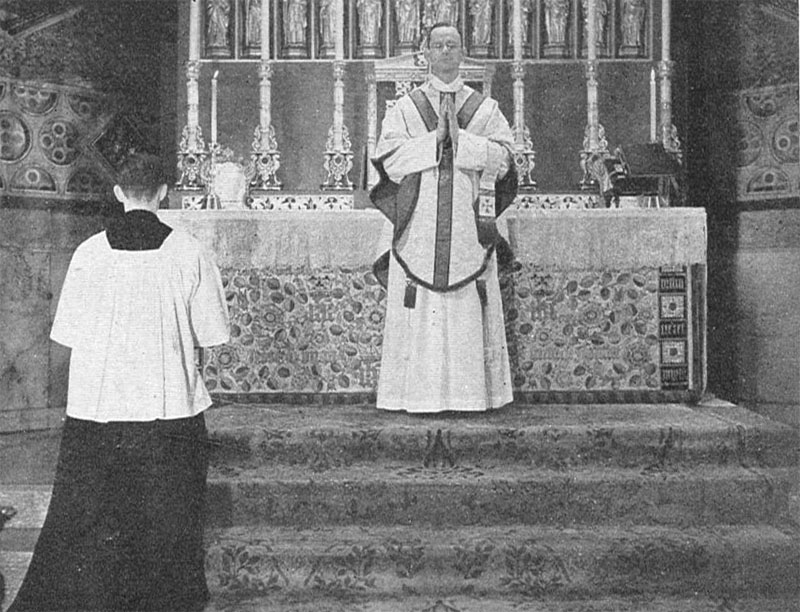

V. The Lord be with you. R. And with thy spirit.

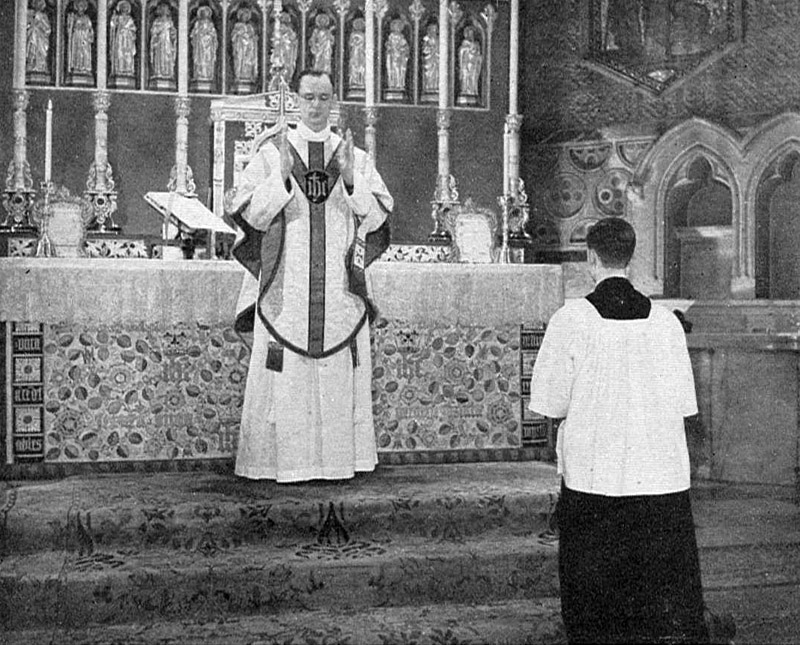

Kissing the altar in the middle as an act of reverence before turning away from it, the priest faces the people for the salutation, to which they make their response. This mutual greeting recurs frequently during the Mass, so that priest and people are reminded of the bond of mutual charity that should bind the members of Christ’s Church together, and of the special part that each plays in the offering of the holy Sacrifice.

The words of the priest’s greeting are of Jewish origin (see Ruth ii. 4), and the parallelism of. the greeting and response also follows Jewish models; it is therefore probable that it was from Jewish usage that the Church in the earliest days adopted the salutation for its own worship.

At this point in the service, the greeting is particularly-appropriate as a reminder that the prayer of the whole Body of Christ is to be offered in the Collect, and that this prayer expresses the charity and brotherhood in which its members dwell.

THE COLLECTS

We beseech thee

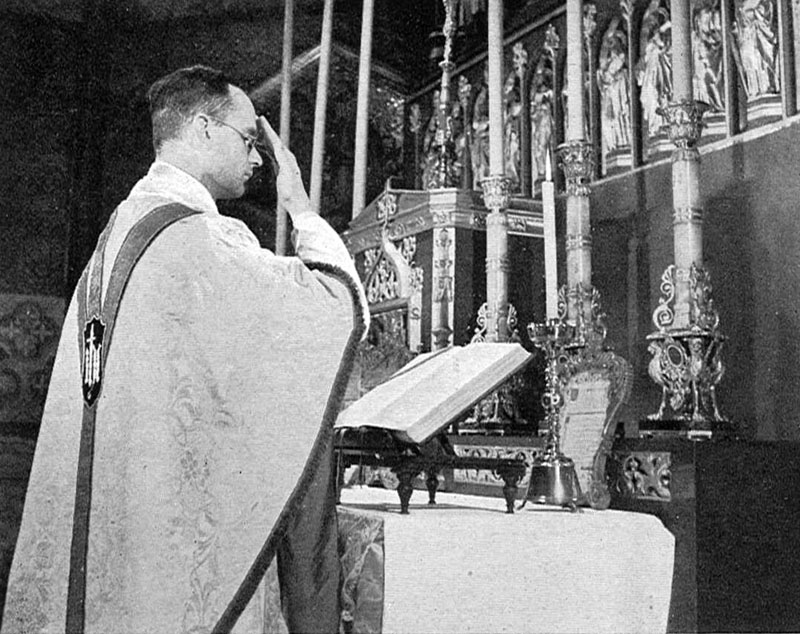

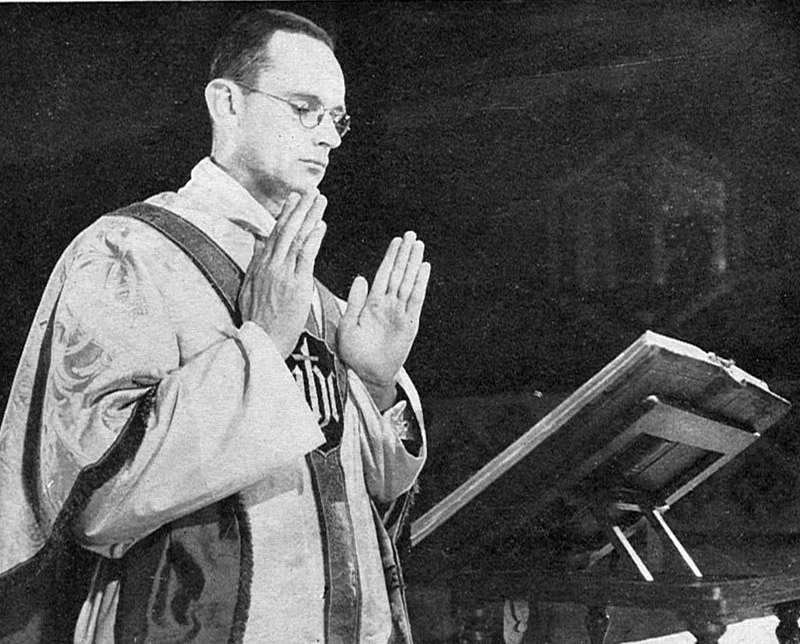

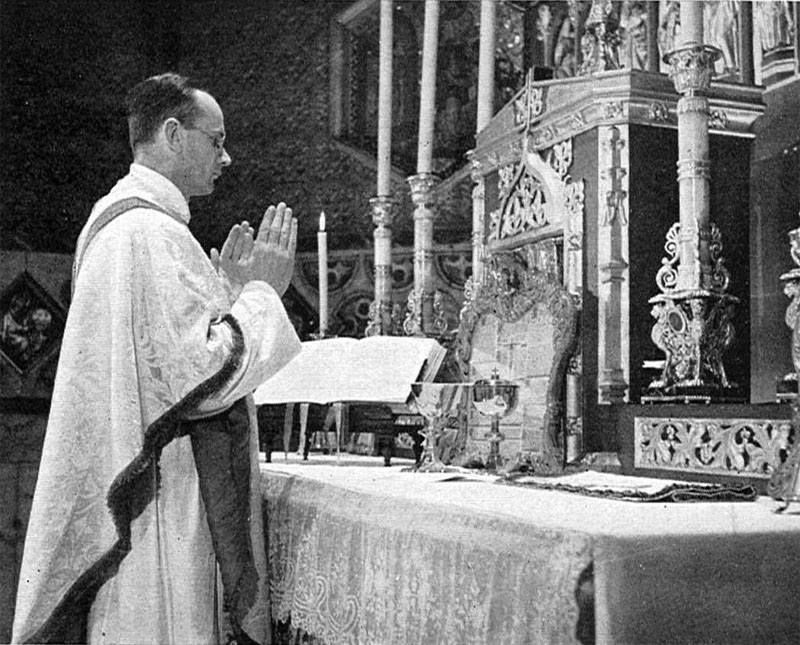

Standing before the missal, the priest bows to the altar cross and says “Let us pray.” Then with extended hands, he says his special prayer of the day, known as the Collect. To this may be added other Collects for special commemorations, or as being suitable for the season.

The name of the Collect may come from its being the special prayer of the Christian “meeting”; it is in any case appropriate as applying to the prayer that “collects” the petitions of the Christian people together. In the Collect we pray for the whole Church of God, in virtue of our union with him through his Son Jesus Christ, and commemorating the events of the Christian year, or praying for special blessings.

Normally the Collects are addressed to God the Father, although some are addressed to God the Son. The blessings for which they ask are such as may fitly be sought “through Jesus Christ our Lord,” and as benefits of his redemptive work.

Written for our learning

After the Collect, the priest lays his hands on the book (since he is taking the place of the subdeacon at High Mass, who holds the book from which he, reads), for the Epistle. An “Epistle” means a “letter,” and the lesson read at this point is generally from one of the letters of the Apostles, to be found in the New Testament. In ancient days other lessons, from the Old Testament, were read before this; later on, the number of lessons was reduced to three: Prophet, Epistle, Gospel. To-day the number has been reduced to two, and the first—the “Epistle”—may come from the Old Testament, or from any part of the New except the four Gospels.

“Whatsoever things were written aforetime were written for our learning”; and it is for the instruction of our souls, and for exhortation to a Christian life, that the words of Prophets or Apostles are read to us. In gratitude for the light of God’s revelation we answer “Thanks be to God” at the end of the reading.

In psalms and hymns

THE GRADUAL

Between the Epistle and Gospel the priest reads the Gradual or other chant which is sung at High Mass at this place. On ordinary days, the psalm-verses of the Gradual are followed by an Alleluia-verse; before Easter the latter part is replaced by a Tract (that is, a chant sung straight through without responses), which was at an earlier date the chant between the Prophetic lesson and the Epistle; and in Eastertide the Gradual is replaced by a special Alleluia-chant. On a few feasts there is further a metrical hymn, the Sequence.

Before the introduction of other chants, such as the Introit or the Agnus Dei, the Gradual was the special chant of the day, and highly regarded in consequence. To this day it provides for that rhythm of praise alternating with learning, of expression alternating with impression, which adds so much beauty to the service of the altar. Frequently the Gradual repeats the theme of the Introit, recalling us to the central ideas of the occasion celebrated.

The glorious Gospel of Christ

THE PRAYERS BEFORE READING THE GOSPEL

Cleanse my heart and my lips, O almighty God, who didst cleanse the lips of Isaiah the Prophet with a living coal: and of thy sweet mercy deign so to cleanse me, that I may worthily proclaim thy holy Gospel; through Christ our Lord. Amen.

Pray, Lord, give me thy blessing.

The Lord be in my heart and lips that rightly and meetly I may proclaim his Gospel. Amen.

Before announcing the Gospel:

V. The Lord be with you.

R. And with thy spirit.

The Gospel is then announced, and the response is made:

R. Glory be to thee, O Lord.

THE GOSPEL

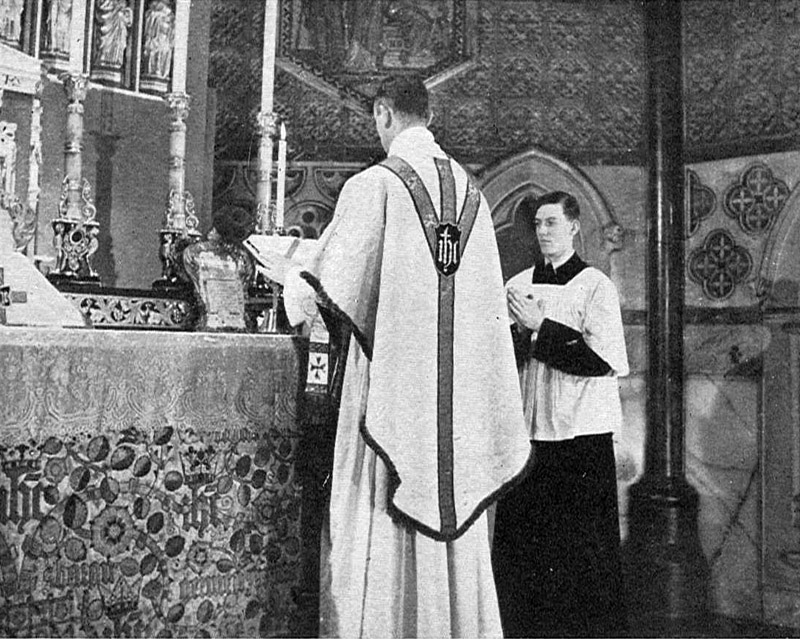

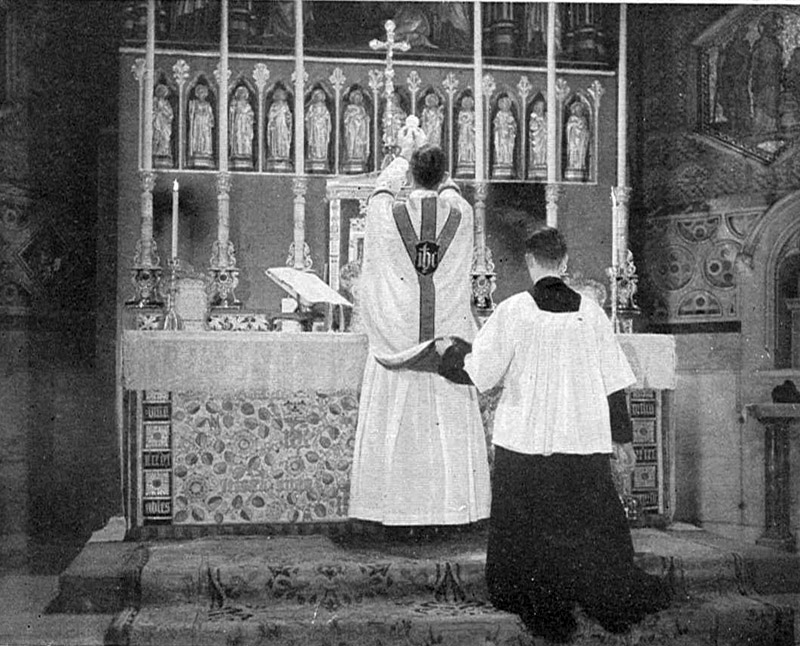

After praying for purity of heart and lips, the priest passes to the north end of the altar to read the holy Gospel. He stands here as being in the position most nearly corresponding to that of the deacon at High Mass, who stands facing north for the solemn chanting of the Gospel. In announcing the Gospel, the priest makes the sign of the cross on brow and lips and breast, to show that we believe and proclaim and love the Gospel of Christ.

In the Gospels we have the inspired record of the deeds and words of our Saviour himself. It is therefore natural that the Church should treat the Gospel-lessons with special honour. In the course of the year they recount to us the story of the earthly life of our Lord, his death and resurrection, and bring before our minds his teaching both by word and by his acts of mercy.

Although the Gospel-reading is one of the earliest elements in the Mass, it was not until the seventh century that the arrangement of the Gospels for each Sunday of the year was completed, and it took even longer for it to become the universal custom. At an earlier date the Gospel for ordinary Sundays was chosen out of a group of suitable passages. The Gospels for special days, such as Easter, were more speedily settled than those for other days.

The Sunday Gospel may well furnish us with material for meditation during the following week. The ancient custom was for the sermon on Sunday mornings to be used for the exposition of the meaning of the Gospel which had just been read.

And was made Man

THE NICENE CREED

I believe in one God, the Father almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of his Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made; being of one substance with the Father; by whom all things were made; who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven; and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, AND WAS MADE MAN. And was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; he suffered and was buried. And the third day he rose again according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven; and sitteth on the right hand of the Father. And he shall come again with glory to judge both the quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord, and giver of life, who proceedeth from the Father and the Son; who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; who spice by the Prophets. And I believe one (holy) catholic and apostolic Church. I acknowledge one Baptism for the remission of sins. And I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

THE CREED

After the words of the Prophets or Apostles, and the Gospel narrative of our Lord’s own deeds and teaching, we profess our faith in the religion they proclaim in the words of the Nicene Creed. This fuller statement of the articles of Faith expressed in the Apostles’ Creed was adopted by the great Councils of the Church at Nicaea (A.D. 325) and Constantinople (A.D. 381), to safeguard the faith from the errors that had been disseminated by heretics.

The use of the Creed at Mass is a comparatively late development; it began in the east, and spread in the sixth century to Spain, after which the emperor Charlemagne introduced it in his chapel in 798. Only after another two hundred years was it adopted as the custom in Rome. As the recitation of the Creed was an addition to the eucharistic rite, it was kept for Sundays and the greater feasts only, and this usage has remained until the present day.

We say the Creed standing, but kneel at the proclamation of our Lord’s Incarnation. The Incarnation is the central truth of Christianity, on which all else depends; it is from the Incarnation that we have learned of the truths of the Holy Trinity, of the office and work of the Holy Spirit; the very existence of the Church has depended on the authority of the incarnate Son of God. In honour of so great a mystery, and in remembrance of the great humility of the Son of God in becoming Man, it is fitting that we should kneel in reverence (cf. Philippians ii. 5-11).

The Creed is not only an affirmation of faith, it is also an act of worship; for it is not only before men but also before God that we make our act of faith. The truths which it enshrines are not only to be accepted with the mind; they change the whole character of our lives; in the light of them we worship and live.

THE EUCHARISTIC ACTION

WITH the Creed we come to the end of the first main part of the eucharistic rite. In it we have offered prayer and praise to God, have listened to the voice of Prophets and Apostles, and to the words of our Lord himself, and have expressed our faith in the revelation that he came to bring. All these are proper parts of the “synaxis,” the “gathering together” of Christian people in God’s house, but they are preliminary to the fulfilment in our worship of the command of our Lord, who on the last night of his earthly life instituted the sacrament of the holy Eucharist, and said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” The second part of the Mass is concerned with this strictly eucharistic action, and with the fulfilment of our Lord’s command.

On the Cross on Calvary our Saviour offered himself for the redemption of the world. On the night before, Maundy Thursday night, he gave us a means of sharing in his own act of offering. As he ever pleads in heaven the merits of his death on the Cross, so at our altars he gives us a means of uniting ourselves with it. The Mass is therefore in the first place not a form of words to be recited, but an act to be done. It is the act not only of the priest at the altar, but of the whole company of Christ’s faithful people, of which he is the minister. The congregation is not a collection of spectators, but a group of active participants in what is being done.

At the institution of the Blessed Sacrament, our Lord performed seven acts of great significance:

1. he took bread;

2. he blessed it;

3. he broke it;

4. he gave it to his disciples;

5. he took the cup;

6. he blessed it;

7. he gave it to his disciples.

Our Lord’s own acts took place in the context of the Last Supper; by its separation from this context, the eucharistic action has become a series of four acts, since the offering of the chalice is no longer separated from that of the bread. We have therefore the following fourfold action of our Saviour as the basis of our eucharistic offering:

1. he took bread and wine;

2. he blessed them;

3. he broke the blessed Bread;

4. he gave the consecrated Bread and Wine to his disciples.

These four acts are therefore the focal points in our eucharistic worship; we give them four names:

1. the Offertory;

2. the Consecration;

3. the Fraction;

4. the Communion.

The rest of this book therefore consists in the illustration of and commentary on these four acts, which have, in the practice of the Church, been accompanied by special prayers to aid our understanding and devotion.

The first of the four acts of the strictly eucharistic rite is then the Offertory, when, after the example of Christ, the Church “takes” bread and wine for the Sacrifice.

THE OFFERTORY

Bread and wine were the ordinary food and drink of man, which our Lord took and put to the most sacred use in his institution of the Sacrament of the Altar. In the ancient record of the book Genesis (xiv. 18, 19) Abram was blessed by Melchisedek king of Salem, who “brought forth bread and wine; and he was priest of the most high God.” In Psalm 110, a psalm which our Lord himself quoted for its prophecy of the Messiah, his eternal priesthood is foreshadowed as being “after the order of Melchisedek”; an idea which is later developed in the Epistle to the Hebrews. The action of our Lord at the Last Supper is therefore one which was bound to recall to the Church the connexion of the offering of bread and wine with the priesthood and sacrifice of its Lord.

The Church takes what Christ took, and offers it to God. In doing so, it not only associates us with the sacrifice of our Redeemer, but brings within the sphere of his oblation all the life of man. For bread and wine are gifts of God, the fruits of the earth that God has blessed; but they are also the fruits of man’s labour, the product of the toil of the husbandman and reaper, of the miller and the baker, the labourers in the vineyard and at the wine-press. Thus to God we bring, in union with the offering of his Son, the whole life of man. Our worship is the token and the safeguard of its being offered to him for whose glory it exists.

Most of the prayers of the Offertory are said quietly by the priest at the altar; it is the acts, not the words, that matter most; the words have come in to interpret the significant acts. Yet the very acts speak to us in a universal language; what is explicit in the words is implicit in them.

I will offer in his dwelling

THE OFFERTORY-ANTHEM

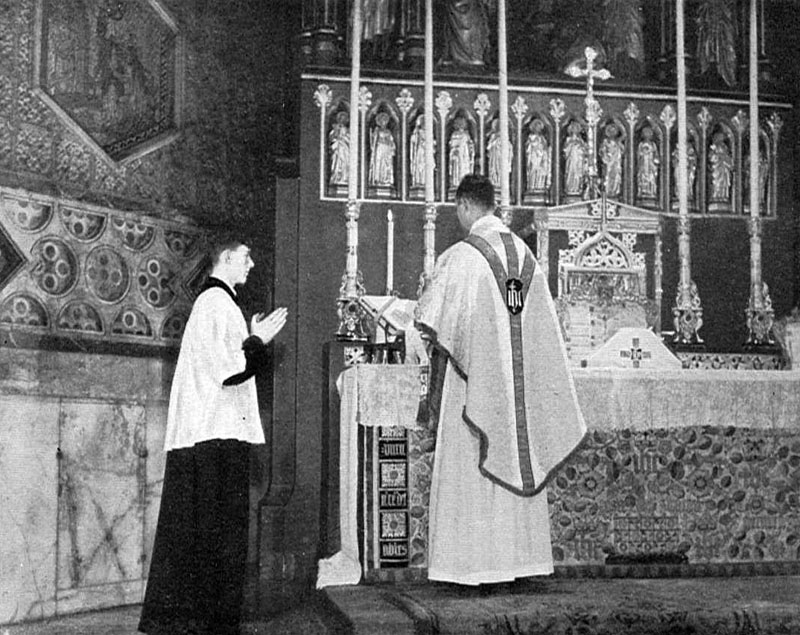

The second part of the Mass begins with the priest first saluting the people with the versicle “The Lord be with you,” and then turning to the altar to read the Offertory-anthem. At High Mass the anthem is sung by the choir during the offering of the bread and wine.

It was in Africa that the custom first arose of singing psalms with antiphons during this part of the Mass, which was at that time a lengthy action, as it included the bringing of offerings in kind by the laity. Of this psalmody all that now remains is the antiphon or anthem. During the fifth century the new custom of singing at this time spread to other parts of the Church. To-day we usually make our offerings in money, although in many parts of the mission-field offerings in kind are still customary.

The words of the offertory-anthems are among the variable parts of the service; they frequently have reference, either to the feast being celebrated, or to the act of offering.

This spotless Host

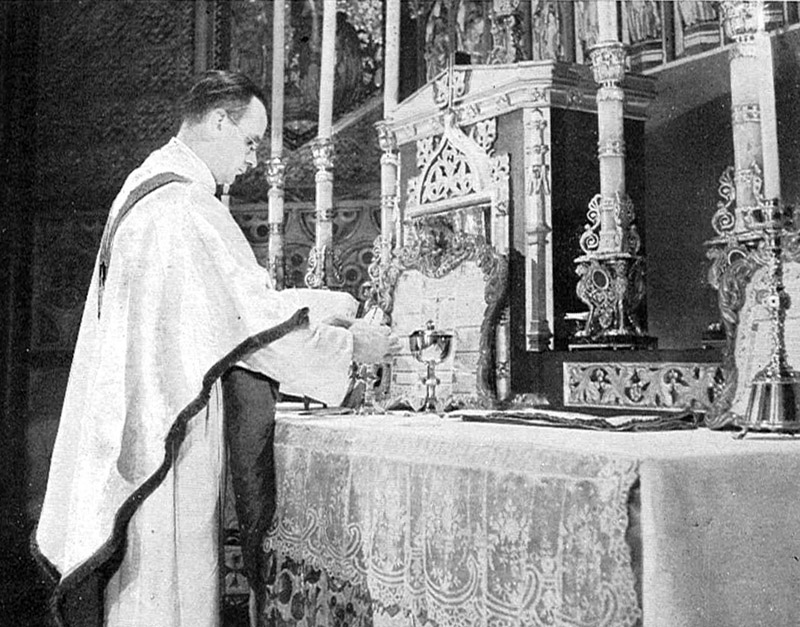

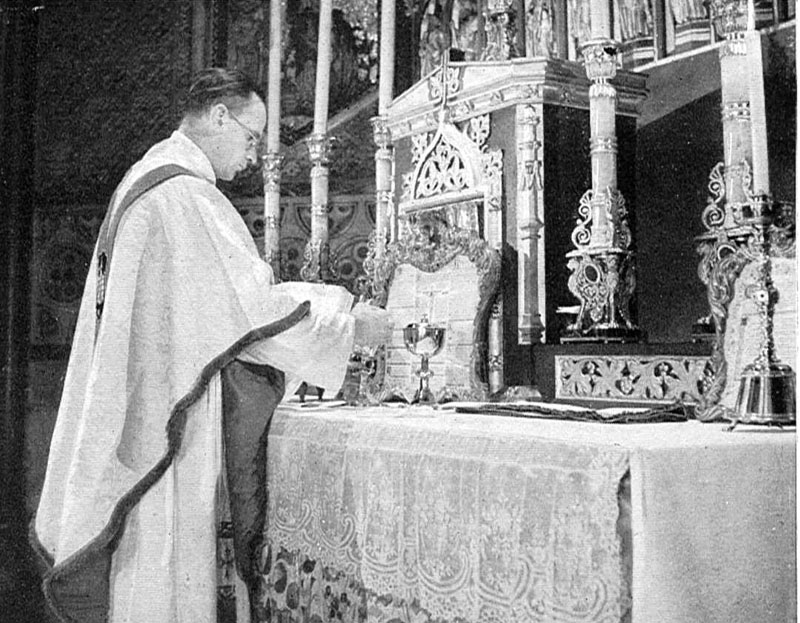

THE OFFERING OF THE BREAD

O holy Father, almighty and everlasting God, take thou this spotless Host, which I thine unworthy servant now present; for thou art my living and true God: so let me plead for all my countless sins, wickedness and neglect; and for all those here present, as also for all the faithful in Christ, both quick and dead, that it may set forward their salvation and mine, till we attain eternal life. Amen.

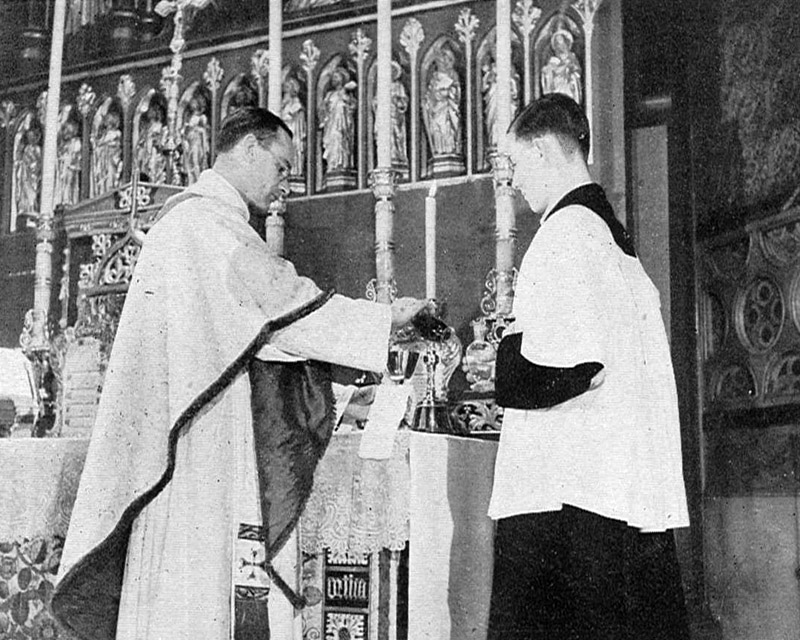

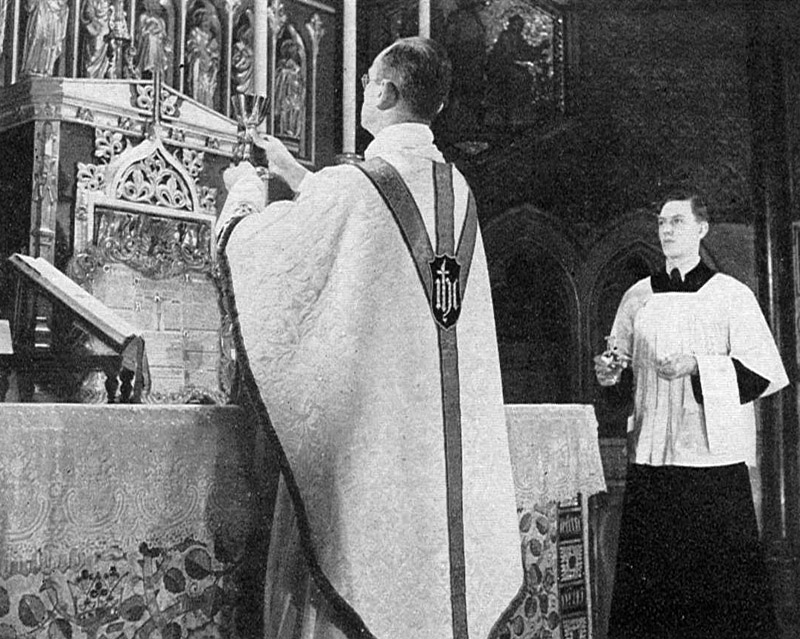

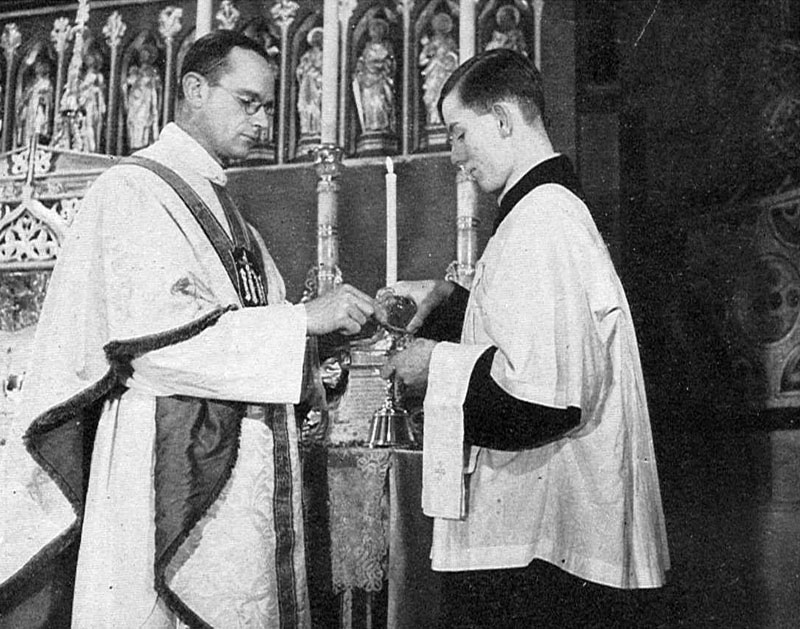

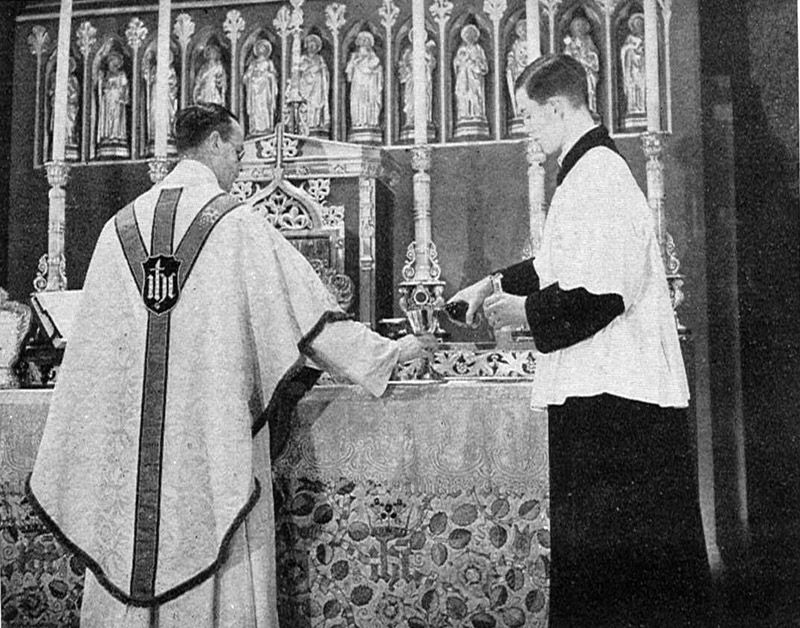

The priest takes the required number of “hosts” or portions of bread. Holding the paten before him, he now offers the bread to God, saying the prayer provided. Then he makes the sign of the cross over the corporal with the paten, and places the host on the corporal, and the paten partly beneath it on the right. If there are many to receive Holy Communion, the hosts for the people are in a vessel called a ciborium (which is rather like a chalice with a lid).

The Mass is offered not only for those present, but for the whole Church; so in the prayer the priest recalls the purpose of the offering “for all the faithful in Christ, both quick and dead.”

The mystery of this water and wine

THE PREPARATION OF THE CHALICE

O God, who hast laid the foundations of man’s being in wonder and honour, and again in greater wonder hast adorned the same: grant that, by the mystery of this water and wine, he who shared with us our human nature may make us to be co-heirs of his very Godhead, even Jesus Christ thy Son our Lord: who liveth and reigneth with thee in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God for ever and ever. Amen.

The priest takes wine in the chalice, from the cruet brought to him by the server; he then blesses the water in the second cruet, and adds a little to the wine in the chalice. The mingling of water and wine goes back to Jewish custom, which was no doubt followed by our Lord. It is a symbol to us of the union of the divine and human natures in our Lord, and of our own inseparable union with him as “partakers of his divine nature” (2 St Peter i. 4).

In the ancient Church the bread and wine were provided by the people as their own offerings; at Rome at an early date orphans, who could make no other offering, brought the water.

The cup of salvation

THE OFFERING OF THE WINE

We here present to thee, O Lord, the cup of salvation; and of thy mercy grant that in the sight of thy divine majesty it may ascend as a sweet-smelling savour for our salvation, and that of the whole world. Amen.

In a contrite heart and an humble spirit let us be accepted of thee, O Lord: and so let our sacrifice be this day that it may be pleasing in thy sight, O Lord God.

Come, thou Sanctifier almighty, eternal God, and bless this sacrifice made ready for thy holy name.

Bringing the chalice to the middle of the altar, the priest raises it before him to offer the wine to God. As the bread, made out of many grains of corn, so the wine, made out of many grapes, teaches us that there is one mystical Body of Christ, of which we are members. We are “one Bread, one Body,” and we all partake of one Cup.

In the words of the book of Daniel (iii. 16), the priest next prays that we may offer the holy Sacrifice in contrition and humility; and then asks for the blessing of the Holy Spirit on our offering.

I will wash my hands in innocency

LAVABO

I will wash my hands in innocency, O Lord: and so will I go to thine altar.

That I may shew the voice of thanksgiving: and tell of all thy wondrous works.

Lord, I have loved the habitation of thy house: and the place where thine honour dwelleth.

O shut not up my soul with the sinners: nor my life with the bloodthirsty.

In whose hands is wickedness: and their right hand is full of gifts.

But as for me, I will walk innocently: O deliver me, and be merciful unto me.

My foot standeth right: I will praise the Lord in the congregations. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son: and to the Holy Ghost.

As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: world without end. Amen.

THE WASHING OF THE HANDS

Before proceeding, the priest washes his hands, so that the offering of the holy Sacrifice may be made with the utmost reverence. While doing this, he recites the Psalm called (after the first word in Latin) Lavabo, to remind himself of the inward purity he ought to have.

Although it has often been assumed that the ceremony of the washing of the hands had a utilitarian origin, St Cyril of Jerusalem definitely states that its purpose was symbolic. It was indeed not the celebrant, but the deacons, who handled the people’s gifts at the Offertory, and whose hands might become soiled. The ceremony is meant to remind priest and people of the inward purity without which we cannot worthily approach the altar of God. We are not to be as those of whom the psalm speaks, “in whose hands is wickedness”; even under the old dispensation it was said “Be ye clean, ye that bear the vessels of the Lord.”

The same lesson applies of course to the Christian people as a whole. It is implied in the use of water for Baptism, the outward sign of the purity of soul imparted by that sacrament; by the use of Holy Water as we enter the Church; and by the ancient ceremony of the Asperges before the chief Mass on Sundays.

At the end of the psalm the priest turns to the altar cross to bow as he says “Glory be to the Father,” except in Masses of the Dead and of Passiontide, when the Gloria is omitted.

This oblation which we present

THE PRAYER OVER THE OBLATIONS

Receive, O holy Trinity, this oblation which we present to thee in memory of the passion, resurrection and ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ; and in honour of blessed Mary ever Virgin, of blessed John Baptist, of the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, of these and all the Saints. Let it be to their honour and our salvation: and grant that while we remember them on earth, in heaven they may plead for us. Through the same Christ our Lord. Amen.

Returning to the middle of the altar, the priest says a further prayer, asking God to receive the oblation of his Church, which is offered in memory of the saving acts of our Lord in the offering of his life for man; in honour of our blessed Lady and the Saints; and for the benefit of the Church on earth. As the Church in heaven and on earth is bound together by the bond of charity, the priest prays that the Saints who are honoured on earth may themselves be aiding us by their prayers in heaven.

Pray, brethren

THE INVITATION TO PRAYER

V. Pray, brethren, that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God the Father almighty.

R. The Lord receive this sacrifice at thy hands, to the praise and glory of his name, both to our benefit and that of all his holy Church.

Previously the priest has invited the faithful to join his prayers in the words “Let us pray.” Now he turns to the people to urge on them the duty of prayer that the holy Sacrifice, which is the common offering of priest and people, may be pleasing in God’s sight. As the response says, the. Sacrifice is offered at the priest’s hands, but it is none the less the offering of the whole Church. There is an element of warning, as well as of courtesy, in the way in which it is given to the priest to remind the people that the Sacrifice is not his alone, and to them to remind him that it is made at his hands. As priest and people have greeted one another with blessing several times already, now they are joined in mutual appeal for reverence in their sacred tasks.

Prayers and Supplications

THE PRAYER FOR THE CHURCH

Let us pray for the whole state of Christ’s Church militant here in earth.

Almighty and everliving God, who by thy holy Apostle hast taught us to make prayers and supplications, and to give thanks, for all men; we humbly beseech thee most mercifully to accept our (alms and) oblations, and to receive these our prayers, which we offer unto thy divine majesty; beseeching thee to inspire continually the universal Church with the spirit of truth, unity, and concord. And grant, that all they that do confess thy holy name may agree in the truth of thy holy Word, and live in unity, and godly love.

We beseech thee also to save and defend all Christian kings, princes, and governours; and specially thy servant N. our King; that under him we may be godly and quietly governed: and grant unto his whole Council, and to all that are put in authority under him, that they may truly and indifferently minister justice, to the punishment of wickedness and vice, and to the maintenance of thy true religion, and virtue.

Give grace, O heavenly Father, to all bishops and curates, that they may both by their life and doctrine set forth thy true and lively Word, and rightly and duly administer thy holy Sacraments.

And to all thy people give thy heavenly grace; and specially to this congregation here- present: that, with meek heart and due reverence, they may hear, and receive thy holy Word; truly serving thee in holiness and righteousness all the days of theft’ life.

And we most humbly beseech thee of thy goodness, O Lord, to comfort and succour all them; who in this transitory life are in trouble, sorrow, need, sickness, or any other adversity.

And we also bless thy holy name for all thy servants departed this life in thy faith and fear; beseeching thee to give us grace so to follow their good examples, that with them we may be partakers of thy heavenly kingdom: Grant this, O Father, for Jesus Christ’s sake, our only Mediator and Advocate. R. Amen.

THE PRAYER FOR THE CHURCH

According to ancient custom, the priest at this point said variable offertory prayers, corresponding in number to the collects; the prayers said here were known, as they were said in silence, as the “secret prayers.” Their place is taken in the Prayer Book rite by the Prayer for the Church Militant. This act of intercession reminds us of the words of St Paul (1 Timothy ii. 1) teaching us to pray and offer thanksgiving on behalf of all men. It is in accordance with this teaching that we now bring before God the needs of the Church and the world. So we pray for Christian rulers, and especially for our own King and nation; for all bishops and curates (that is, those with the cure or care of souls); for the congregation present before the altar; and for those in any trouble or need. To these prayers we add our thanksgiving for the good examples of those who have died in the Christian Faith.

THE ACT OF PENITENCE

The penitential devotions that follow are part of the preparation for receiving Holy Communion, and would be more fittingly placed immediately before the act of Communion, where they were to be found in the First English Prayer Book, following the arrangement of the old Latin service books. Although these devotions are not part of the Offertory, it will be convenient to comment on them at this point, since they are found here in the present English Prayer Book.

By thought, word and deed

THE EXHORTATION

Ye that do truly and earnestly repent you of your sins, and are in love and charity with your neighbours, and intend to lead a new life, following the commandments of God, and walking from henceforth in his holy ways: draw near with faith, and take this holy Sacrament to your comfort; and make your humble confession to almighty God, meekly kneeling upon your knees.

THE GENERAL CONFESSION

Almighty God, Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, Maker of all things, Judge of all men; we acknowledge and bewail our manifold sins and wickedness, which we, from time to time, most grievously have committed by thought, word and deed, against thy divine majesty, provoking most justly thy wrath and indignation against us. We do earnestly repent, and are heartily sorry for these our misdoings: the remembrance of them is grievous unto us: the burden of them is intolerable. Have mercy upon us, have mercy upon us, most merciful Father; for thy Son our Lord Jesus Christ’s sake forgive us all that is past; and grant that we may ever hereafter serve and please thee in newness of life, to the honour and glory of thy name: through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

THE GENERAL CONFESSION

In the earliest days of the Church, the prayers of the Liturgy were wholly concerned with the corporate offering of the holy Sacrifice. There was no place in it for the kind of prayers, so typical of the devotion of the Middle Ages and of modern times, which are concerned, even when they are written in the plural number, with the piety of individual Christians, and especially with the individual’s receiving of Holy Communion. This does not of course mean that such devotions are to be regretted, but it does mean that they are secondary in importance in the service of the altar.

Such a devotion is the Confession of sin that precedes the receiving of Holy Communion. Penitence is part of the due preparation for receiving the Blessed Sacrament, and in the General Confession the communicants make a public act of contrition, and ask for pardon for the sake of Christ their Saviour.

In receiving Holy Communion we are seeking to be united with him who is to be worshipped in spirit and in truth; before him there can be no insincerity. In his presence we see ourselves as we are, creatures before our Creator, and sinners before the All-holy. Penitence for our sins is therefore the necessary attitude of our souls as we come to receive the most holy Sacrament.

To penitence must be added the desire for amendment, and it will be in the strength that is given to us through the life of Christ imparted in the Blessed Sacrament that we shall be able to walk “in newness of life.”

Pardon and deliver you

THE ABSOLUTION

Almighty God, our heavenly Father, who of his great mercy hath promised forgiveness of sins to all them that with hearty repentance and true faith turn unto him: have mercy upon you; pardon and deliver you from all your sins; confirm and strengthen you in all goodness; and bring you to everlasting life: through Jesus Christ our Lord. R. Amen.

THE COMFORTABLE WORDS

Hear what comfortable words our Saviour Christ saith unto all that truly turn to him.

Come unto me all that travail and are heavy laden, and I will refresh you. So God loved the world, that he gave his only-begotten Son, to the end that all that believe in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. Hear also what St Paul saith.

This is a true saying, and worthy of all men to be received, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.

Hear also what St John saith.

If any man sin, we have an Advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous; and he is the propitiation for our sins.

THE ABSOLUTION

After the General Confession the priest turns from the altar to say a General Absolution. Even though we avail ourselves of the Sacrament of Penance regularly, or at least when mortal sin lies heavy upon the conscience, yet from day to day and from moment to moment we stand in need of God’s forgiveness for the countless sins into which in our weakness we fall. The Church assumes that we are all sinners as we approach the altar, and so gives the opportunity for cleansing from all our stains a few moments before the act of receiving the precious Body and Blood of Christ.

All forgiveness is through the power of his Cross; the priest therefore makes the sign of the cross over the people as he speaks of God’s pardon and deliverance. It is customary for the people to sign themselves at the same time.

THE COMFORTABLE WORDS

After the Absolution, the priest proceeds to pronounce the “Comfortable Words.” These are not represented, in the ancient liturgies, and reflect the liking of the sixteenth century for hortatory formulas. The texts read are selected as conveying the assurance of salvation through our Lord Jesus Christ, and of forgiveness through his self-offering.

It will be noticed that the translation of the words of these sentences is not that of the Authorized Version in general use; the translation was taken from the Great Bible of 1539, and was not altered when the Authorized Version was published in 1611.

THE CONSECRATION

THE second act of our Lord at the Last Supper was to bless the bread and wine that he had taken. The Church follows his example in the Liturgy at the Consecration. In the strictest sense the name is used for the central act of this part of the service, the recital of the words of institution in prayer over the bread and wine; but Consecration is the theme of all that is included between the short dialogue before the Preface and the Amen after the Doxology.

The Offertory is the gift of men to God, made through their union with Christ; the Consecration is also effected “through Jesus Christ our Lord,” and depends on his action through his mystical Body the Church; it is the occasion of God’s great gift to man. The gift is no less than the presence of our incarnate Lord in his Body and Blood, under the sacramental veils. It is therefore with the deepest reverence that we must approach so great a mystery.

The doctrine of the Real Presence, like all other doctrines, takes us beyond the limits of our human understanding. Yet the idea of God’s presence in any way is bound to be beyond our complete comprehension. In one way, he is present to us in the world of nature; in another he is present in the soul by grace; in the earthly life of our Lord he was present by means of our human nature; and the incarnate presence is still with us in the most holy Sacrament. We rightly see in the blessed Eucharist a special fulfilment of our Lord’s own words: “Lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.”

As with the Offertory, the action again is the primary thing; it has been enshrined in the solemn words of Christian liturgy, so that as far as possible its meaning may be made explicit.

Lift up your hearts

THE PREFACE

V. The Lord be with you.

R. And with thy spirit.

V. Lift up your hearts.

R. We lift them up unto the Lord.

V. Let us give thanks unto our Lord God.

R. It is meet and right so to do.

It is very meet, right, and our bounden duty, that we should at all times, and in all places give thanks unto thee, O Lord holy Father almighty, everlasting God.

(A “proper” section may follow here.)

Therefore with Angels and Archangels, and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify thy glorious name, evermore praising thee, and saying:

THE PREFACE

The section of the eucharistic rite which enshrines the Consecration begins with the chant known (since it introduces the consecratory prayer) as the Preface. After greeting the people, the priest calls on them to lift up their hearts to God, a solemn invitation as he and they enter into the sacramental presence of our Lord. Then, raising his eyes to heaven and then bowing at the divine name, the priest adds “Let us give thanks unto our Lord God.” We have to remember that the word “eucharist” itself means “thanksgiving,” and that the offering of the holy Sacrifice is the supreme act of thanksgiving that we can perform.

After the response “It is meet and right so to do,” the priest continues “It is very meet, right, and our bounden duty, that we should at all times and in all places give thanks,” reminding us that through all the ages and all over the world it is the privilege and duty of Christian people to “make eucharist,” and thereby to manifest their gratitude to God.

The Preface, as it leads on to the Sanctus, has on certain feasts and in certain seasons a “proper” section, commemorating a particular mystery, and at one time the number of these was far greater than it now is. Probably the original Prefaces were all “proper” ones, with the idea of a “common” Preface gradually developing out of their use. The present practice represents the typical restraint of western custom, and has the added advantage of heightening the significance of the proper Prefaces when they occur.

The use of the Preface can be traced back to the beginning of the third century in Alexandria, and probably is so ancient as to be a part of original Christian practice taken over from Jewish worship.

Holy, holy, holy

SANCTUS

Holy, holy, holy Lord God of hosts, heaven and earth are full of thy glory. Glory be to thee, O Lord most high.

BENEDICTUS

Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.

THE PRAYER OF HUMBLE ACCESS

We do not presume to come to this thy Table, O merciful Lord, trusting in our own righteousness, but in thy manifold and great mercies. We are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs under thy Table. But thou art the same Lord, whose property is always to have mercy; grant us therefore, gracious Lord, so to eat the Flesh of thy dear Son Jesus Christ, and to drink his Blood, that our sinful bodies may be made clean by his Body, and our souls washed through his most precious Blood, and that we may evermore dwell in him, and he in us. R. Amen.

SANCTUS AND BENEDICTUS

The Preface passes into hymns of praise: the Sanctus, the hymn of the Angels as Isaiah saw them in his vision (Isa. vi. 1-8), and John in the Revelation (iv. 6); and the Benedictus, the hymn of welcome to our Lord as he entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. At High Mass the hymns are sung by the choir. When they were first introduced in the west, in the fifth century, their use seems to have been limited, like that of the Gloria to-day; to certain masses; afterwards they became an invariable part of the rite.

Isaiah tells us that the seraphim that he saw in his vision covered their faces with their wings; with the same sense of awe, the celebrant bows as he uses the Angels’ hymn. At the beginning of the Benedictus he signs himself with the cross, asking as it were a blessing from the Lord whose own blessedness he proclaims.

As we draw near to the climax of our worship, it is fitting that we should join in the song that expresses the perfect worship of heaven; from this we turn to that which is not only one of welcome, but was also the herald of the passion.

THE PRAYER OF HUMBLE ACCESS

The prayer that follows, not to be found in the ancient liturgies, expresses our unworthiness to come to the Table of the Lord, and asks for cleansing through the Body and Blood of Christ. It would more fittingly come just before the Communion, for which it is a preparation. The purpose of our receiving the Blessed Sacrament is that we may abide in Christ, as he himself tells us (St. John vi. 56), and live by his life. We cannot of ourselves be worthy of his coming, but only by the gift of his grace.

A perpetual memory

THE PRAYER OF CONSECRATION

Almighty God, our heavenly Father, who of thy tender mercy didst give thine only Son Jesus Christ to suffer death upon the Cross for our redemption: who made there, by his one oblation of himself once offered, a full, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world: and did institute, and in his holy Gospel command us to continue, a perpetual memory of that his precious death, until his coming again.

THE PRAYER OF CONSECRATION

The dialogue and Preface have led us, through the Sanctus, into the prayers of the “Canon of the Mass.” The word “Canon” means “rule,” for here we have a prayer that does not change from day to day (as, for example the Collects do), but is a constant feature of the service. In the Prayer Book text the Canon is represented by two prayers, known as the Prayer of Consecration and the Prayer of Oblation.

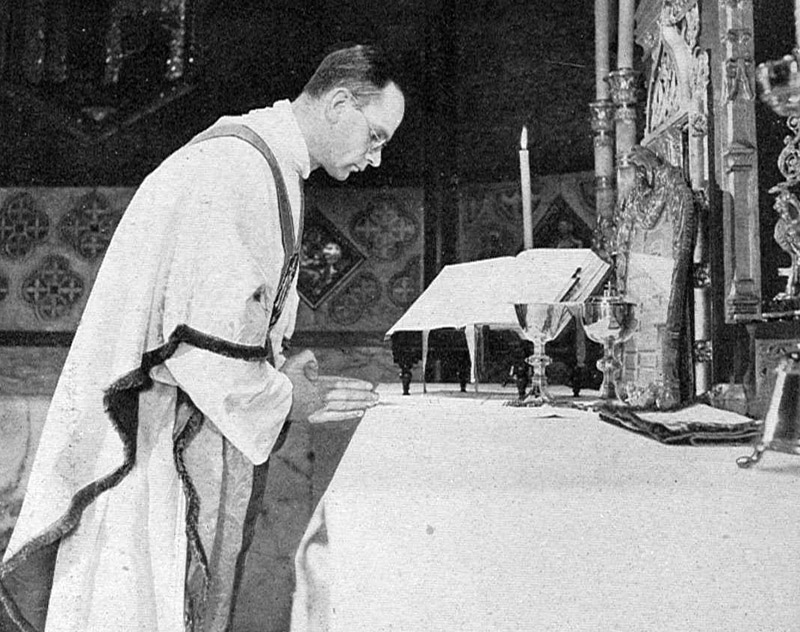

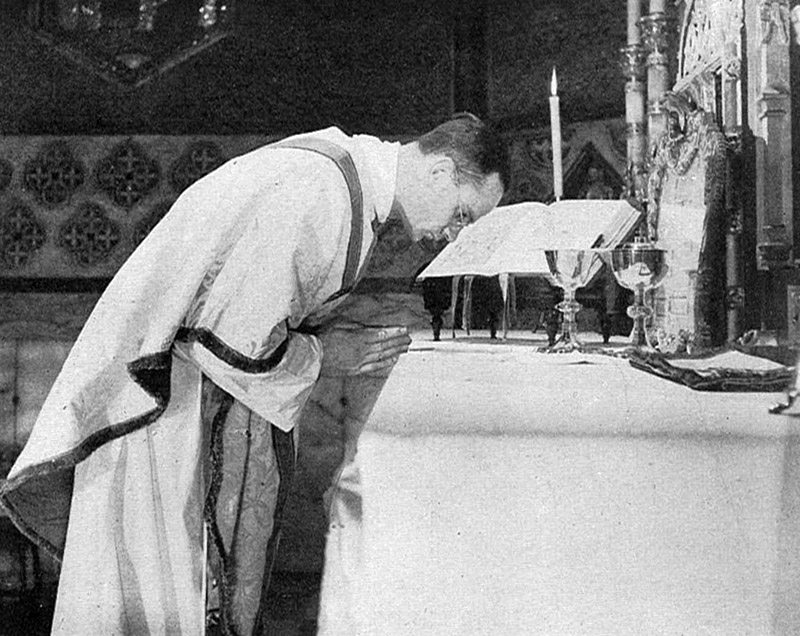

In the midst of the altar, the priest opens and raises his hands, as though silently calling down the blessing of heaven, and then joins them and bows to kiss the altar in reverence for the sacred gifts that are to lie upon it. He begins the Prayer, making the sign of the cross over the oblations.

The prayer is addressed to God the Father, who gave his Son to die on the Cross to redeem us. By that death our Lord has done something for man that no other could do, offering an all-sufficient Sacrifice. To this Sacrifice we are united by the will of our Lord himself, as on the night before he died he instituted the holy Eucharist to be a perpetual memorial of his death on Calvary, until his coming again (1 Cor. xi. 26). Our offering of the holy Sacrifice is not something apart from his offering on the Cross, but the means by which we are made to partake in his offering, as it is also the means by which we partake of his life.

The blessed Eucharist is then the heart of Christian worship; from the earliest days the Catholic Church has expected its children to be “steadfast . . . in the breaking of bread” (Acts ii. 42); for it is in this offering that we are united to the redemptive activity of their Lord.

Hear us, O merciful Father

THE PRAYER OF CONSECRATION

Hear us, O merciful Father, we most humbly beseech thee; and grant that we receiving these thy creatures of bread and wine, according to thy Son our Saviour Jesus Christ’s holy institution, in remembrance of his death and passion, may be partakers of his most blessed Body and Blood.

THE PRAYER OF CONSECRATION

(continued)

As he continues the prayer, the priest spreads his hands over the oblations, indicating by his action, as he does at the same time by the words of the prayer, the desire of the Church that God will send his blessing on the gifts on the altar.

The gift of man to God is that of bread and wine, themselves the creatures of the God to whom they are offered. God’s gift to man is his Son, the Bread of life, and the true Vine. As our bodies are nourished by bread, so our souls are nourished by the Body of the Lord in the most holy Sacrament; as our bodies are refreshed by “wine that maketh glad the heart of man,” so our souls are refreshed by the precious Blood of the Saviour.

The Sacrifice of Christ was the offering of perfect obedience; he came into the world to do the will of his Father. The eucharistic Sacrifice is also offered in obedience, “according to our Saviour Jesus Christ’s holy institution,” and in fulfilment of his command. By uniting ourselves to him, we are making our wills one with his, so that in all things we may obey his heavenly Father.

The obedience of our Lord led him to the death of Calvary; of that death the sacred Mysteries are a perpetual memorial. By the indwelling of Christ in our souls through the Blessed Sacrament, we shall in our turn be able to endure all the sufferings of this life, and to make them an offering to God.

The Church’s prayer therefore is not merely part of a rite to be performed; it is the plea for that intervention of God into our lives that will transform them; being “partakers of the divine nature” we shall, here in this world, “have eternal life.”

This is my Body

THE CONSECRATION OF THE BREAD

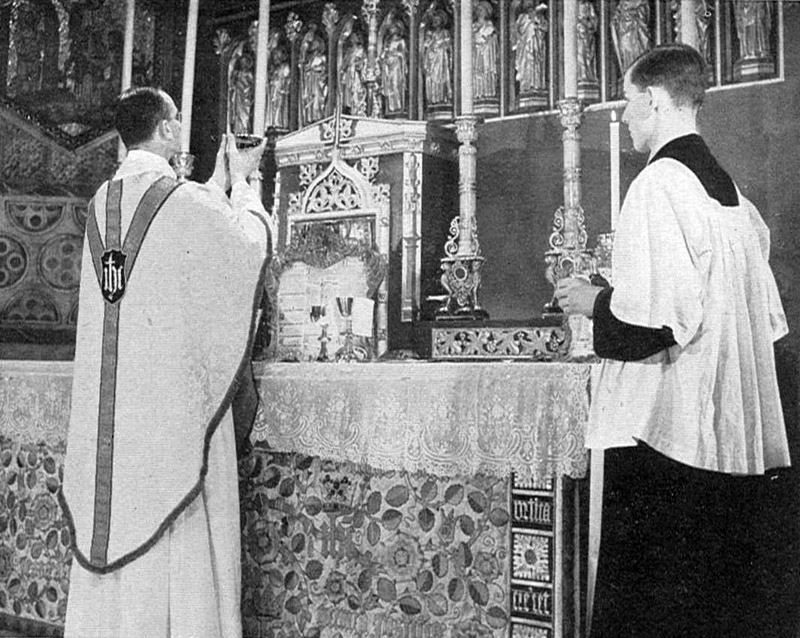

Who in the same night that he was betrayed, took bread; and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and gave it to his disciples, saying: Take, eat,

THIS IS MY BODY WHICH IS GIVEN FOR YOU,

Do this in remembrance of me.

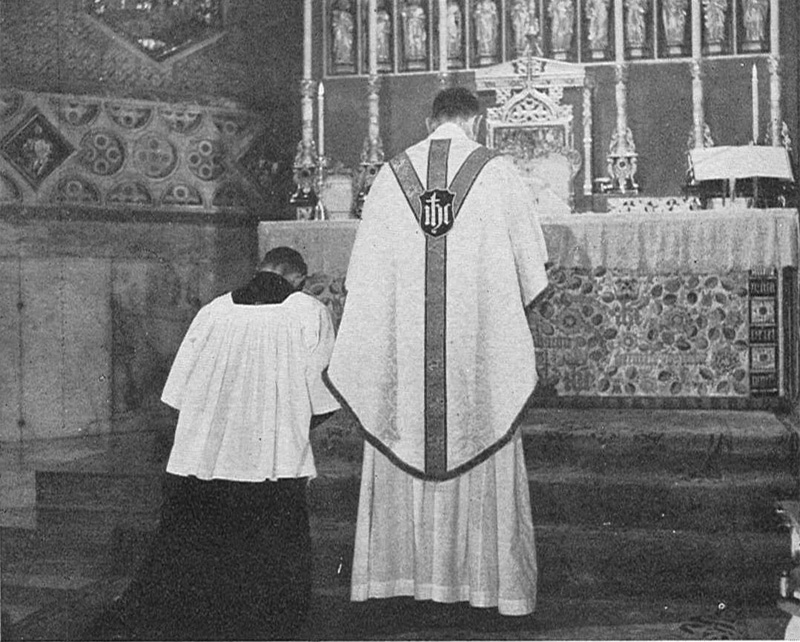

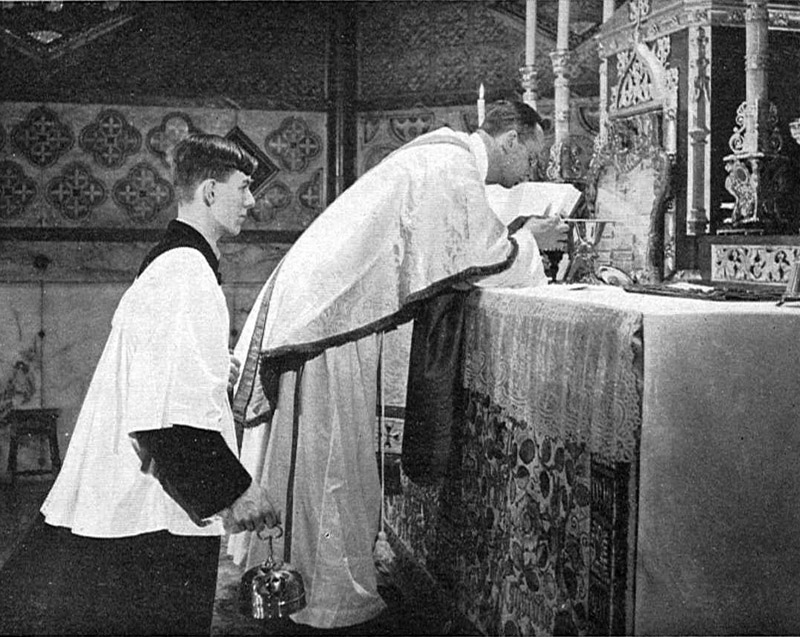

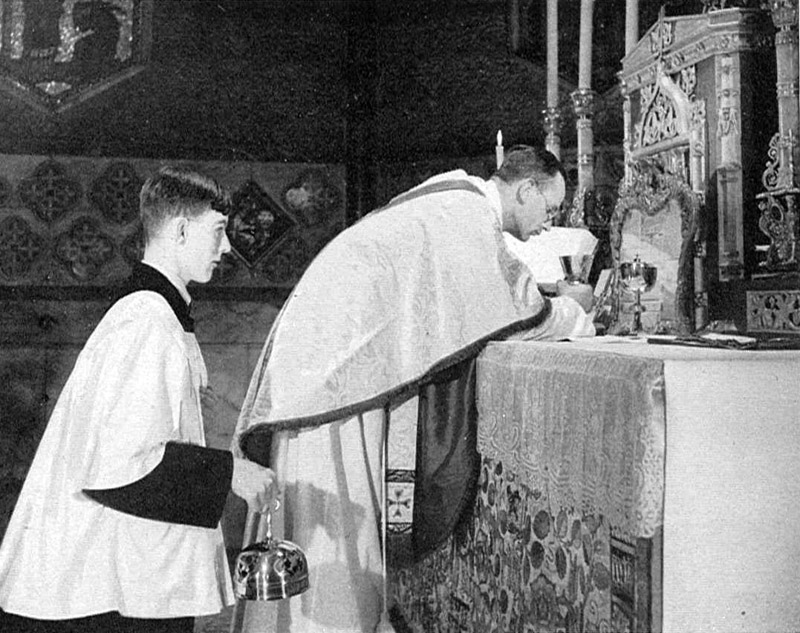

Bending over the altar, the priest, holding the host in his hands, utters the words of consecration—the same words that our Saviour himself used at the Last Supper. The great mystery that is accomplished is not merely the fulfilment of a command of Christ, but is his own act; and it is as though speaking in the person of the Lord that the priest speaks the sacred words.

By the act of consecration the bread that was the natural food of man becomes the Body of Christ, which is truly present though hidden under the sacramental veil. All the beauty of Catholic worship is meant to provide a fitting setting for the act in which he comes to us, and a shrine as worthy as we can make it for his presence.

My Lord and my God

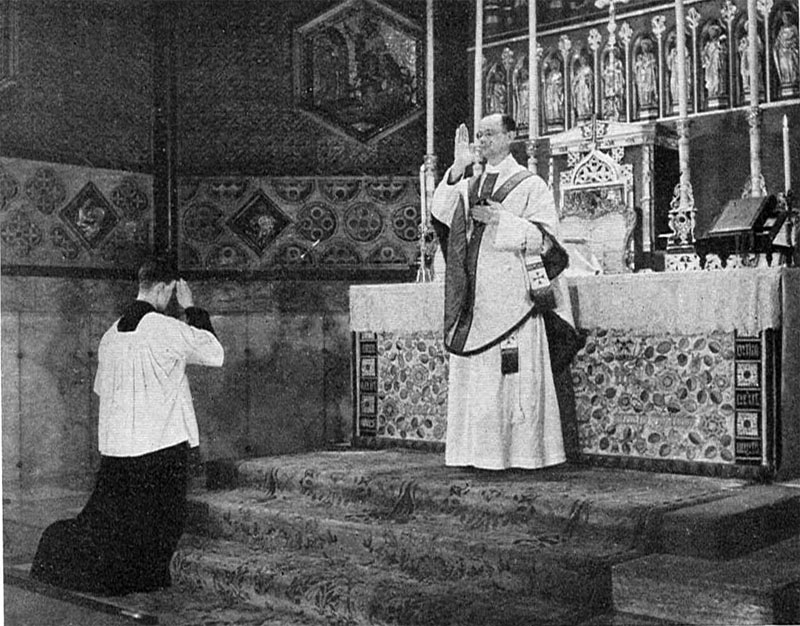

THE ELEVATION OF THE HOST

After uttering the words of consecration, the priest bows the knee in adoration at the presence of our Lord in his holy Body; raises the Host for the people to see and adore; and bows the knee again. At each of these three acts a bell is rung as a signal to the people.

The elevation of the Host was introduced into the Mass as a result of the change from the older custom of the celebrant standing at the east of the altar, facing west, to that of the present eastward position. It represents the persistent desire of western Catholics to see the action of the Mass as fully as possible, since it is an action in which they have so real a part. This intimacy which we are given with the most sacred of Christian rites only increases our need for the greatest reverence; and when we see the sacred Host raised up for our adoration, we may well join in the words of St Thomas, when he recognized the presence of the same Master, and say with him: “My Lord and my God.”

This is my Blood

THE CONSECRATION OF THE WINE

Likewise after supper, he took the cup; and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying: Drink ye all of this,

FOR THIS IS MY BLOOD OF THE NEW TESTAMENT

WHICH IS SHED FOR YOU AND FOR MANY FOR THE REMISSION OF SINS.

Do this, as oft as ye shall drink it, in remembrance of me.

After the elevation of the Host, the priest replaces it on the corporal, and having genuflected, uncovers the chalice for the consecration of the wine. Again bowing over the altar, he takes the chalice into his hands, says the words of consecration.

The Blood of Christ is the Blood of the New Testament; by it is sealed the New Covenant between God and man, replacing the Old Covenant that was also ratified in the offering of blood, “the blood of the Covenant that the Lord God made” with the old Israel (Exodus xxiv. 8). Not from one nation only, but out of every ‘nation has Christ redeemed us by his Blood (Rev. v. 9); it is for men of all nations that the Sacrifice of the altar is offered.

My Lord and my God

THE ELEVATION OF THE CHALICE

After the consecration of the Wine, the priest genuflects, elevates the chalice, and then genuflects again; the bell rings as before.

In his death on the Cross, the precious Blood of Christ was poured out for our salvation. The separate consecration of the Wine at the altar vividly presents before our eyes the meaning of the offering he made, the Sacrifice of one who laid down his life for us. As we have already adored him present in his sacred Body, so we now adore him present in his precious Blood, which was the price of our redemption. Again we may utter the Apostle’s words: “My Lord and my God.”

The consecrated Gifts are now on the altar, and our Lord’s own words have been said; although we cannot express in words all that this means, the priest continues in the following prayer to express some of its implications.

Humbly beseeching thee

THE PRAYER OF OBLATION.

Wherefore O Lord and heavenly Father, we thy humble servants entirely desire thy fatherly goodness mercifully to accept this our Sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving: most humbly beseeching thee to grant, that by the merits and death of thy Son Jesus Christ, and through faith in his Blood, we and all thy whole Church may obtain remission of our sins, and all other benefits of his passion.

And here we offer and present unto thee, O Lord, ourselves, our souls and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy and lively sacrifice unto thee: humbly beseeching thee, that all we, who are partakers of this holy Communion, may be fulfilled with thy grace and heavenly benediction.

And although we be unworthy, through our manifold sins, to offer unto thee any sacrifice: yet we beseech thee to accept this our bounden duty and service; not weighing our merits, but pardoning our offences.

THE PRAYER OF OBLATION

The holy Mass is a Sacrifice offered to God for four purposes: in it we offer him worship, since sacrifice is the recognition of his supreme dominion; we offer him our thanks, as indeed we specially show by our use of the word “eucharist” or “thanksgiving”; we offer him propitiation for sin, which is an offence to his divine majesty; and we offer him a sacrifice of entreaty, that he may give us the blessings we need. All these four themes are to be found in the Prayer of Oblation with which the Canon continues. Making the sign of the Cross over the sacred Gifts, the priest asks God to accept that which is “our Sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving,” because the worship and thanks we give are part of the offering of our Lord himself present under the sacramental veils. Then he prays, on behalf of the whole Church of God, that the fruits of the passion and death of our Lord may be obtained by the remission of sins. After which he bows down, in sign of our offering of “ourselves, our souls and bodies” in virtue of our union with Christ, whose own self, soul and body are offered to his Father; and beseeches God that his grace and blessing may be imparted to all who partake of this Sacrifice.

It is not through any merits of our own that we dare approach God with offerings. In penitence, the priest beats his breast as he admits that we are unworthy, through our manifold sins, to make an offering to God; yet he prays that God will accept this Offering that we make as “our bounden duty,” laid upon us by his Son, whose members we are.

It is the action of Christ that matters; it is his Sacrifice that is acceptable. Those who are made members of Christ dare to come to God through him, who is our way and truth and life.

Unto thee, O Father

Through Jesus Christ our Lord; by whom, and with whom, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, all honour and glory be unto thee, O Father almighty, world without end. R. Amen.

THE DOXOLOGY

The Canon draws to a close with a doxology. All that we have done and said has been “through Jesus Christ our Lord,” as indeed all our prayers and actions are offered to God through him. The inadequacy of our own souls is supplemented by his all-sufficiency; or rather it is taken up into the fulness of his holiness and power. So the priest goes on to say that all honour and glory should be unto God “by him,” for every man that comes to God must come through him and by his enabling; and “with him,” since the honour and praise paid to his Father must be inseparably connected with that paid to the divine Son “in the unity of the Holy Ghost.”

The prayer ends with the words that so often carry us to the remembrance of the changeless eternity of the threefold Godhead: “world without end.” At the end of the prayer there comes the affirmation of the Christian people: “Amen.” This is the “Amen at the giving of thanks” (1 Cor. xiv. 16) which is the assertion of the people’s being identified with the eucharistic prayer of the priest, and which it is their great privilege to utter.

During the doxology, the priest uncovers the chalice, and having made the sign of the cross with the Host over it, elevates the Host and chalice together, in the ancient ceremony that marked the end of the prayer, and showed the consecrated Gifts that the people were to receive. This primitive ceremony still remains, although we now have the elevations at the Consecration (which are much later in origin) made in order to call forth our adoration of Christ in his presence at the altar.

THE FRACTION

THE third thing that our Lord did at the Last Supper was to break the consecrated Bread; the Church follows his example in the Fraction.

Not only was the Fraction originally a following of the example of him who instituted the Blessed Sacrament, but it served also the practical purpose of preparing the Sacrament for the people’s Communion. This practical need has now ceased, through our modern custom of using separate hosts; but it was the time taken over this action that suggested the singing of the Agnus Dei as a hymn at this point.

The breaking of the consecrated Bread has a further significance. The natural Body of Christ was broken on the Cross for our salvation; on Easter Day it was reunited to his soul in the Resurrection. So in the Fraction the consecrated Host is broken, and a part is put into the chalice, as though to remind us of the first Easter. The historical origin of this practice is perhaps to be found in the old custom of a fragment of the Host from the bishop’s Mass being taken to altars in other churches, to show the unity of all our Eucharists. This fragment (known as the fermentum) may have been put into the chalice at this point of the service. At a later stage the “commixture” came to be regarded as a sign of our belief in the presence of the one Christ, who gives himself to us through Host and chalice.

Through the broken Body of Christ came our peace; the message of peace is to be heard through the prayers that accompany the Fraction at Mass.

In the breaking of Bread

Let us pray.

As our Saviour Christ hath commanded and taught us, we are bold to say:

Our Father, which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, in earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation.

R. But deliver us from evil.

Deliver us, O Lord, we beseech thee, from all evils, past, present, and to come: and at the intercession of the blessed and glorious ever Virgin Mary, Mother of God, with thy blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and with Andrew, and all the Saints, graciously grant us peace in all our days, that by thine availing mercy, we may ever be free from sin and safe from all distress. Through the same Jesus Christ thy Son, our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God for ever and ever. R. Amen.

THE LORD’S PRAYER AND THE FRACTION

To the modern worshipper it may seem strange that the Lord’s Prayer was not found in the earliest forms of the eucharistic rite; yet it may serve to remind him that the liturgy has developed from action to word, rather than from word to action. The petitions of the Lord’s Prayer are so obviously appropriate, teaching us to pray for our daily bread, and to seek for forgiveness from sin, that sooner or later they were certain to find their way into the order of the Mass, as an act of preparation for the receiving of Holy Communion.

At some time in the fourth or fifth century the use of the Lord’s Prayer began to be common; the place at which it was said still remained uncertain. Its present position is due to St Gregory the Great, who also inserted the following prayer, that takes up its petition for deliverance. It is due also to his devotion to the Apostle St Andrew that this unexpected name occurs in this prayer.

The Lord’s Prayer is introduced by a special formula, which reminds us that just as the offering of the holy Sacrifice is an act of obedience to our Lord, so also the use of the Lord’s Prayer is “as our Saviour Christ hath commanded and taught us.” The priest continues the prayer, and then the people respond with the last clause. It is this petition for deliverance from evil that the priest resumes in the following prayer. As he says it, he first breaks the Host in two, and then breaks off a small part from one of the two fragments, which is soon to be put into the chalice.

As we have, in the Lord’s Prayer, used the family prayer of the Church, it is appropriate that in the following prayer we should remember the communion of Saints, and ask for the intercession of our Lady and all the Blessed.

The peace of the Lord

V. The peace of the Lord be alway with you.

R. And with thy spirit.

May this mingling and consecration of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ our Lord be unto us who receive it an approach to everlasting life.

THE COMMIXTURE

“Peace be unto you” was the greeting of our blessed Lord to his disciples. Together with “The Lord be with you” it became the greeting also of the liturgy of the altar. Gradually it became the distinctive greeting of the bishop, while priests used the second form; but in one place the greeting of peace remains. After the prayer for deliverance at the end of the Lord’s Prayer, the celebrant, making the sign of the cross three times over the mouth of the chalice with the fragment of the Host he has broken off, greets the faithful with the words “The peace of the Lord be alway with you.” And, after the agelong custom of the Church, the people make their constant reply “And with thy spirit.”

The Commixture follows. The priest puts the fragment of the Host into the chalice, from which he will himself receive it when he makes his Communion. As he puts the fragment in, he prays that those who receive Christ’s Body and Blood in the Blessed Sacrament, now mingled and consecrated in the chalice before him, may receive the gift of everlasting life.

We have already seen that the Commixture may have arisen through the custom of the bishop sending the fermentum to the altars where his priests were celebrating. We may well use this little ceremony to recall our own unity with the Church through all the ages. The very tradition of Catholic custom binds us to our forefathers in the Faith, and that which they used to represent the unity of all Christian people may well serve to represent to us our unity through all time, as well as all over the world.

O Lamb of God

AGNUS DEI

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world: have mercy upon us.

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world: have mercy upon us.

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world: grant us thy peace.

(Or, in Masses of the Dead:

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world: grant them rest.

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world: grant them rest.

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world: grant them rest everlasting.)

O Lord Jesu Christ, who saidst to thine Apostles: Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you; regard not our sins, but the faith of thy Church; and grant her that peace and unity which is agreeable to thy will: Who livest and reignest, God, for ever and ever. Amen.

AGNUS DEI AND THE PRAYER FOR PEACE

Bowing in adoration, the priest recites (as the choir at High Mass sings) a hymn to our Lord, the Agnus Dei. It is the first formula of the Mass that is addressed to our Lord himself, and calls him by his sacrificial title of “Lamb of God.” The hymn was introduced by Pope Sergius I at the end of the seventh century, in order to occupy the time taken by the breaking of the consecrated Bread for distribution at the Communion; in his own words “at the time of the breaking of the Lord’s Body.”

In its original form, the same petition was sung twice, the third and slightly different petition being added, at about the time of the Norman Conquest, in the churches of France. About the same period, the variation for use in Masses of the Dead was also introduced in France, again with a third, and slightly different, petition after the first two similar ones.

At each of the three petitions of the hymn, the priest beats his breast in penitence, before the Lamb that bore our sins in his own Body on the tree.

The Agnus Dei is an act of worship and petition addressed to our Lord in his eucharistic presence. The last petition (“grant us thy peace”) links it to the preceding greeting, and is again taken up in the following prayer, in which the priest, before receiving the Blessed Sacrament, prays for the peace of the Church. At High Mass the ceremonial “Kiss of Peace” follows, so that the same theme recurs through this part of the rite. Although the primitive practice of greeting with the Kiss of Peace was not at first in its present position, the order of the prayers as we have them is natural and fitting.

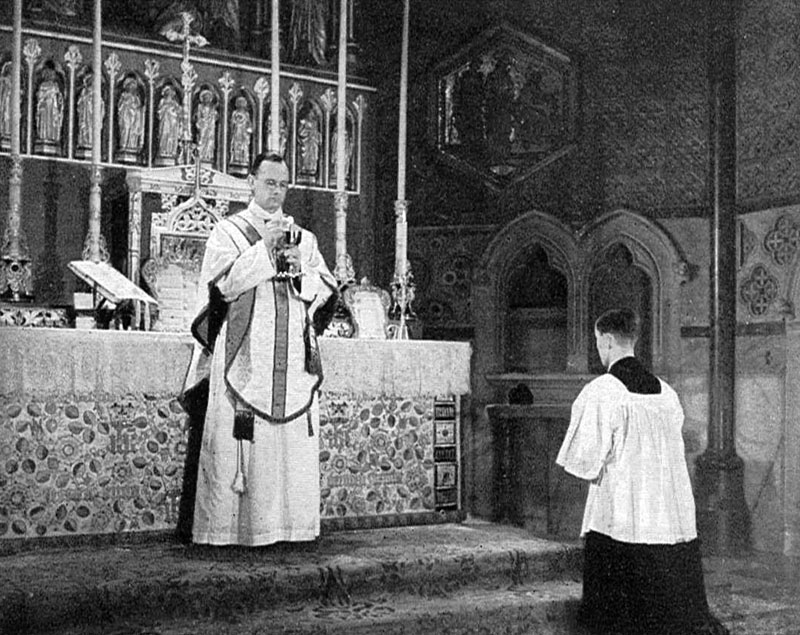

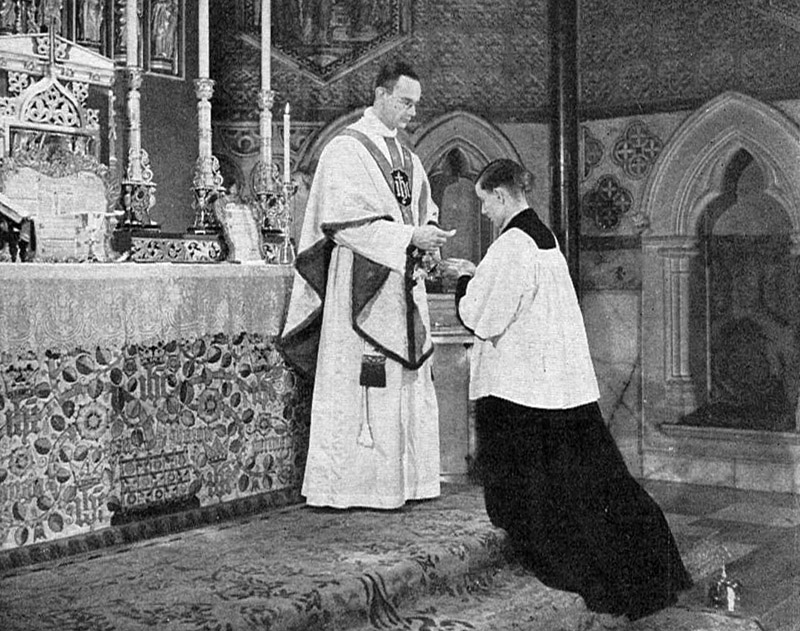

THE COMMUNION

THE fourth thing that our Lord did at the Last Supper was to give the disciples the sacred Gifts of his Body and Blood in Holy Communion. The Church therefore now passes to the fourth part of the eucharistic action: the Communion. It consists of prayers before Communion, the actual reception of the Blessed Sacrament, and prayers afterward.

The Communion is an essential part of every Mass, and at least the celebrating priest is bound to receive the most holy Sacrament. If the holy Sacrifice is offered at a time when there are no others to do so, those present should at least associate themselves with the priest’s Communion by an act of spiritual Communion.

By the law of the universal Church, we are required to receive Holy Communion at least once a year, at Eastertide. By the law of the Church of England, we are also required to make our Communions at least on two other occasions in the year. We should prepare for our Communions by prayer, by penitence for our sins (and when necessary by seeking Absolution in the sacrament of Penance), and by fasting from the preceding midnight.

The Blessed Sacrament was the weekly Food of the members of the early Church, and frequent Communion should be the practice of all who are striving to lead a devout Christian life.

Our Lord himself has spoken of the blessings that are conferred on those who feed on his sacred Body and Blood. Through the Blessed Sacrament they enter into the eternal life which Christ imparts to his disciples even here on earth; in it they find the pledge of their immortality; and by it they are strengthened to do God’s most holy will.

Lord, I am not worthy

THE PRAYERS BEFORE THE PRIEST’S COMMUNION

O Lord Jesu Christ, Son of the living God, whom the Father with the Holy Ghost ordained by death to make the world to live; by this most holy Body and Blood of thine, set me free from all my sins, and from all evil things: and so may I ever abide in thy commands that I be never separated from thee: who with the same God the Father, and Holy Ghost, livest and reignest, one God, world without end. Amen.

O Lord Jesu Christ, I, thine unworthy servant, do presume to take thy Body: but let not this act be to my judgement and condemnation; rather of thy mercy, let it ward me in body and soul, and shew thy healing forth in me: Who livest and reignest with God the Father, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen.

Lord, I am not worthy that thou shouldest come under my roof, but speak the word only, and my soul shall be healed.

Before the priest’s Communion, he bows down in prayer for the worthy receiving of the Blessed Sacrament. As we are about to receive the sacred Body and Blood of our Lord we are bound to be conscious of our unworthiness, and to pray God to make us worthy. The Body and Blood of the Lord are given us for the hallowing of our souls and bodies; through them we dwell in Christ and he in us (St John vi. 56).

After praying, the priest beats his breast three times, as he says, in the words of the centurion at Capernaum: “Lord, I am not worthy that thou shouldest come under my roof.”

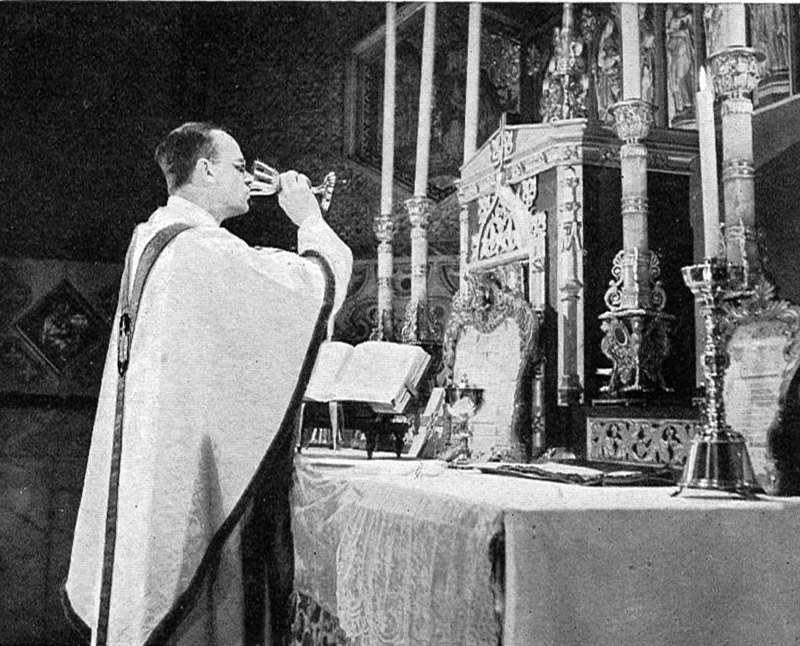

The Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ

THE PRIEST’S COMMUNION