BISHOP G. L. KING THE MAN AND HIS MESSAGE

A MEMOIR WITH A FOREWORD BY THE BISHOP OF ST. ALBANS

LONDON

|

Transcribed by Wayne Kempton

Archivist and Historiographer of the Diocese of New York, 2014

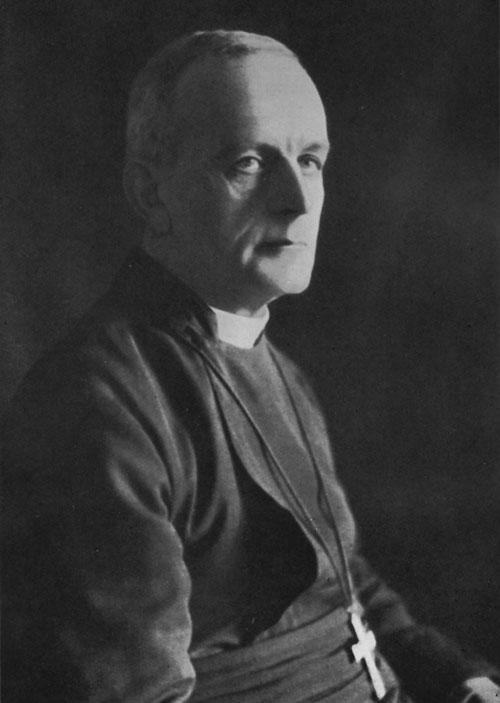

BISHOP GEORGE LANCHESTER KING

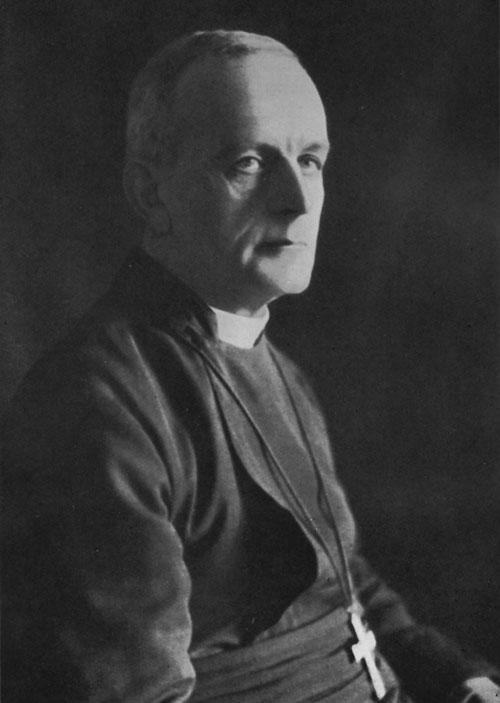

AN AUCKLAND GROUP IN THE EIGHTIES

TYNEDOCK DAYS

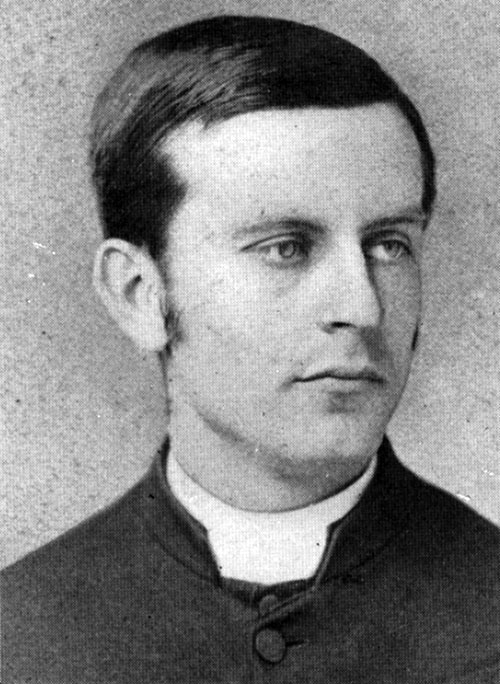

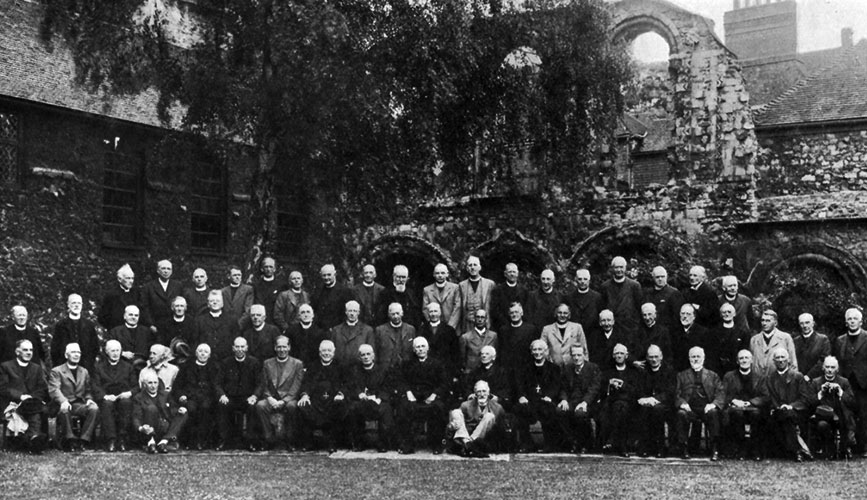

ST. PETER'S DAY, ROCHESTER, 1936

FOREWORD

"GOOD wine needs no bush," and this delightful little Memoir needs no "Foreword." That was my first reaction to the kind request of the Author to me to write one, and yet to refuse seemed to be ungracious and ungrateful. Bishop George King's many old friends--on Tyneside, in Madagascar, indeed all over the world, through their contacts with him when he was Secretary of the S.P.G., as well as those who knew him in his last years of work in the Diocese of Rochester--will, I know, welcome and read it, Foreword or no Foreword, and be all the better for doing so; but there are others who never knew him. It is to such, especially if they are clergy, young or old, that I would commend it as very well-worth their while to read and inwardly digest.

It tells of an Englishman who was endowed with good but not brilliant brains: who could, say what he had to say, but was no orator: who knew what he wanted, and generally got it, but not through being what the newspapers would describe as "forceful": who was full of sound common sense and had a good business head on his shoulders, but was no "super-business-man"--yet, nevertheless, did the biggest thing that is given to any man to do: he got the best out of all sorts and conditions of men and women, young and old, by bringing them to know and love and serve our Blessed Lord, and go on doing so with real joy in their hearts.

And what was the secret of his power? First and last because he was a man of God, and all his long life he was continually learning to. be a better one. [ix-x] That, after all, is the only thing that matters in a priest or bishop--or indeed in any other Christian man or woman--and certainly the only thing which will win others to Christ.

But nobody can be a man of God who does not put God first in his thoughts, his desires, his ambitions, his work and in the ordering of his daily life. George King did that, for he was a man of prayer. He knew this was the root of all else, so it was that he made it his business to teach others to be the same. He did not, as so many of us are content to do, merely exhort people to pray; he taught them how to do it. His teaching in this, as in all else, was from first to last rooted and grounded in the historic Creeds of Christendom, in the sacraments of the Catholic Church, in the steady and systematic study of the Bible and in the writings of the great Christian theologians, ancient and modern.

"A man of God" and "a man of prayer" and therefore "a man under Orders," ready to go anywhere or do anything. He was, I suspect, more surprised than anyone else was at being asked to do any of the jobs he actually did. It was, I am sure, this sense of being "a man under orders" that gave him that courage, serenity and strength which saved him from getting fussed or worried by the difficulties and problems of his work, and gave others such confidence in the soundness of his judgment and counsel.

A man of God, a man of Prayer and a man under Orders. It seems to me these are the three characteristics which most need cultivating among those of us who are called to the Ministry of Christ's Church, especially in these days when everything seems to move at anything from forty to four hundred miles an hour and "there's no time to be quiet, read, think or pray"; [x-xi] when the mechanization of human life threatens to become another "false God" and "Get on or get out" the chief end of man.

It is good then to be reminded once again, as we are in this Memoir of Bishop George King, of the things in any man's life and work which really and therefore eternally matter.

MICHAEL, ST. ALBANS.

Ascension Day, 1941INTRODUCTION

"THE congregation will remain seated, the candidates will stand, for they are to receive a message from the Most High." So spoke Bishop Woodford of Ely to two hundred candidates for confirmation in St. James' Church, Bury St. Edmunds, in the year 1874. Those words rang in the ears of George Lanchester King from the time he heard them until the end of his life in 1941.

He did "receive a message from the Most High" that day, and he lived the rest of his life learning it and passing it on.

It may be a truism to say that everyone has a message of his own to pass on, but everyone does not listen for it, nor is it always successfully transmitted. All who knew Bishop King were conscious that he had something quite distinctive and personal to give to those who came to him for help and guidance, and also that he knew what his message was to the Church in his generation. He made no claim for himself to originality of thought, or wide and accurate learning, or philosophic thinking, but to the very end of his long life he never left off the duty and delight of serious theological reading. He always emphasized that there is a world of difference between the priest who humbly believes that his sermon is a message from God to His flock and one who does not; between the man who asks himself what has he to preach about and the man who asks God what He wishes him to say. It is the latter who speaks from vocation, as called by God who puts words into his mouth, and so gradually the message comes.

[xiv.] And yet Bishop King was well aware of the dangers that beset a man who acts on this conviction. What spiritual pride, what arrogance, what intolerance of others' opinions crouch at the door ready to spring! He knew that at times, to be true to God's leading, an address or a sermon that might impress with its originality or be regarded as striking or popular must be laid aside and a very plain and simple message substituted. "Purple patches" must be avoided at all costs.

There is the obverse side of the picture also. If words come too easily and readily there is the danger of God's message being left to the impulse of the moment, instead of being won by hard thinking, study, prayer and careful preparation. The dangers that lie in wait for a priest who is conscious of a message to deliver are many and insidious.

Again, a prophetic message may be unpopular. The prophets often found this was true, and the Son of Man Himself, who spoke "the things that were given him of his Father," had to face rejection. It is here that the sense of vocation steels the heart against fear. God's word, whether welcome or not, must be delivered. Only let the messenger be sure that it is delivered as persuasively and tactfully as possible.

As we follow Bishop King's life on earth it will be seen that his message grew with his years in certainty and definiteness, and his life falls into six periods: his early life; his apprenticeship, when he was learning his task; his life on the Tyneside; his life in Madagascar; his five years as Secretary of the S.P.G,; and his closing years in Rochester.

CHAPTER I

EARLY YEARS

"With parted lips and outstretched hands."GREAT Barton Place in the County of Suffolk, where George Lanchester King was born on December 5, 1860, was a typically English country home. He was the fourth son of his parents and had three sisters older than himself. A younger brother and two other sisters completed the family. The land had been in the possession of his mother's family for generations; she was a Miss Lanchester and it was from her that the boy received his second name. His father, William Norman King, was much respected and beloved in the county as a Justice of the Peace, Guardian of the Poor and holder of various public offices. He was a keen sportsman and attended all the meets of the fox hounds in West Suffolk. On one historic occasion he was accompanied by his four sons, the youngest being mounted on a small white pony. It was only many years later that the boys realized their father gave up hunting to enable him to pay their university expenses.

George's mother was a clever, cultured and very affectionate wife, and it is to her that he owed his glorious sense of humour. He would often exclaim at the end of his life, "What lucky children we were!"

In later years the Bishop would tell Confirmation candidates that before his first Communion his mother said to him, "You will kneel at the Communion rails between your father and me; try to forget the clergyman and think only of Christ." It was after this that his mother also called him and said, "Now that you are [1/2] confirmed, I think you had better choose, will you learn the Thirty-Nine Articles by heart or take a Sunday School class?" George chose the former, but after two Sundays at the Articles decided that a Sunday School class was the lesser of the two evils!

The eldest son went to Uppingham, but the other three were educated at the Grammar School at Bury St. Edmunds and at Cambridge University. The Grammar School was an old foundation and strong on the classical side under its head master, the Reverend W. H. Wratislaw. George was an apt pupil and passed quickly through the forms to be captain of the school. When he left in the summer of 1879 he had won two gold medals, Bishop Blomfield's for scholarship and another but rarely given for general efficiency. He also won two scholarships to Cambridge, one from his school and one from Clare College. In those days Clare was not a large College and it was a very friendly one, the second and third year men mixing freely with the others. He got his colours for football and cricket in his first year, and was coached for the Boats. He made friendships which lasted for his lifetime. One of these was with Owen Seaman, later editor of Punch, who lived on the same staircase. In later years their paths did not often cross, but they always kept in touch, and when Seaman was given a baronetcy, King wrote to congratulate him and received the following characteristic card from 2 Whitehall Court:

"My Lord Bishop

I thank you from a swelling heart

For being glad I am a Bart

O.S.

But my dear King of old Clare days why this formality of 'Sir Owen'?"[2/3] He worked hard and steadily and was rewarded by getting into the top of the Second Class Honours in Classics.

As was to be expected he took an interest in things religious while up at Cambridge but was never in a pietistic set. He also fell a victim, as men preparing for Holy Orders usually did, to a Sunday School Class of unruly boys, and "sat under" the Reverend J. J. Lias on Sunday evenings at St. Edward's.

After Cambridge he had four terms as classical master at Woodbridge School and picked up there much useful training which stood him in good stead in after life. His contact with Dr. Wood, the head master, was the means of his introduction to Bishop Lightfoot of Durham. John Wood was a student at Auckland Castle and he and his father suggested that George might meet the great bishop with a view to his possibly inviting him to join his band of students.

To anyone who has ever touched even the fringe of that wonderful "Auckland Brotherhood" it conjures up such a unique and beautiful memory, but to the men who formed it and made it, it was a burning and a shining light in their lives, and was so sacred and holy a possession that they always spoke of it as a thing apart.

To quote the Bishop's own words:

"In January, 1884, I went up to Bishop Auckland and joined the band of nine men from Oxford and Cambridge who were admitted by our beloved Bishop Lightfoot as 'sons of the house.' It was a great event. The Bishop was so fatherly, so strong and so humorous; my fellow students represented all types of churchmanship. We were known in the diocese as 'The Lambs' but it was a title we tried hard not to deserve. My first introduction to Bishop Lightfoot [3/4] had been in Lollards' Tower in Lambeth Palace; he was seated at a table, writing, the floor strewn with letters like leaves of a tree in autumn. He always required a personal interview before he took men into his household.

"With his supreme and kindly influence on our lives at Auckland Castle came also that of George Rodney Eden, his first Chaplain and newly-appointed Vicar of Bishop Auckland. He was later to become Bishop of Dover and then of Wakefield. We also had as temporary Chaplain Armitage Robinson, afterwards Dean of Westminster and later of Wells. His truly wonderful lectures at the early hour of 7.15 a.m., on St. Matthew's Gospel, were our first introduction to the art of devout meditation on Holy Scripture.

"We went to Eden once a week for a lecture on pastoral work, and we also had lectures from Borough Southwell on doctrine and history and profited greatly from his manly high churchmanship.

"But as is often the case, there was a closer influence from daily intercourse and friendship with the eight other men who were students with me at the Castle: truly each of us might say 'What have I that I did not receive?' The main idea about our future ministry which we imbibed during our months of training was that it was a high honour to be called to serve in the diocese of Durham, that we must work to the last ounce of our strength and stay where we were put. Two very special friendships which have meant much to me all my life were formed here with F. C. Macdonald and A. C. Fraser. Neither belonged to my own school of thought, but we took no account of 'schools of thought' at the Castle, and theological differences were seldom mentioned. Lightfoot's historical churchmanship was good enough for us.

"I was ordained deacon, with others, in the parish [4/5] church of Bishop Auckland on Trinity Sunday, 1884. We had a moving appeal from the Bishop in his charge on Saturday night, and a grand sermon on 'Shew me thy glory' on the Sunday evening. On Monday morning the Bishop said good-bye to each alone in his study with real emotion and in words too sacred to bear repeating.

"We were ordained priests the following year, and I vividly recollect F. C. Macdonald turning to me, immediately after the service, with blazing eyes and saying, 'King! it is for life!"

George was singularly fortunate in his first vicar, the Reverend E. Fenton: he had been selected by Bishop Lightfoot as the first vicar of a newly-made parish in Tudhoe Grange, because he was one of the hardest working curates in Jarrow. He was young, enthusiastic and forceful, and was ably assisted by his wife. Things went with a swing in that mining parish, and when fifty years later Bishop King went up to help to keep the jubilee of the parish many a white-haired man came up to him and said, "Ay, but you clouted me over the lugs as a boy!"

In 1885 he was joined, by his youngest sister, Gertrude, who remained with him almost continuously wherever his lot was cast until his marriage in 1921. It was a partnership in life and work which meant much of joy and happiness to both of them.

All pulled their weight in Tudhoe Grange and a great deal of parochial work was accomplished. In after life Bishop King was wont to compare the life of a young priest to-day with his in that mining village, and bewail the committees and meetings and services that now seem to prevent the thorough, daily, systematic visiting which they did then. He would admit, with a chuckle, that [5/6] they were terribly parochial; they believed most fervently in salvation through the parish church, and he always said he felt that in his heart of hearts his vicar was never quite sure that his parishioners would enter Paradise safely unless they had taken in, and read, the parish magazine! But with all his parochialism, salvation by Christ through word and sacrament was plainly preached.

From time to time fresh light broke in upon the young priest from a valued friendship with Hastings Rashdall, who at that time was lecturer at Durham University. He would walk over to Tudhoe Grange or invite George to stay a night with him in College. Rashdall would propound original and seemingly unorthodox views and many years later, shortly before his death, he laughingly told his wife, "King used to say in those old days that my ideas might be all very well in their way, but that they would not do for Tudhoe Grange, and that used to settle it for him!" Occasionally Rashdall would come to preach for them in their church to try out an extempore sermon, which must have been somewhat halting as one woman remarked, "If that young man wanted a call anywhere he would have to learn to preach better." There can be no doubt that this friendship stimulated thought and helped George to fresh mental efforts. From the earliest days of his ministry up to within a month of his last illness he always managed to give some time daily to serious theological reading, and his sermons were always most carefully thought out and prepared.

The humdrum parochial life always had two special days of refreshment each year at Auckland Castle, on one of which the unbeneficed clergy met and heard addresses [6/7] from such men as A. J. Mason and Edward Talbot; the other day was always St. Peter's day when the "Brotherhood" rolled up to surround their beloved Bishop Lightfoot and renew their friendships with one another. At these gatherings the bishop gave them of his very best in his address in chapel.

Another great influence in George King's life at this time was Canon Body, a great Mission preacher and a still greater teacher in quiet days and retreats. Durham owed him, as they owed so much else, to Bishop Lightfoot who brought him from a country rectory in Yorkshire, made him Canon of Durham and gave him charge as Canon Missioner of the parochial mission work of the diocese. Lightfoot believed in choosing good men and in giving them a free hand in the task allotted to them. Some may still be alive who remember his ringing words, at his second episcopal visitation, in which he spoke of "my Canon Missioner" who had, as he thought, been treated inconsiderately by the then Archbishop of York. Canon Body inaugurated annual retreats for priests and both the vicar and curate of Tudhoe Grange would leave the parish work undone for four days in order to attend them.

In the summer of 1889 George went to be curate at Holy Trinity, Gateshead, to the Reverend H. W. Stewart who became a valued and lifelong friend. This curacy lasted only for a year but once again it was a time in which many friendships were made and much valuable training was learnt. Mr. Stewart was a sound Catholic, candid and sympathetic, and helped his curate to shed a good many ideas about parochial life which he brought with him; he also stimulated his thought and reading.

The work among the choirboys and elder lads of the [7/8] parish was one which George King thoroughly enjoyed. He used to tell the story of how his vicar taught him the most effective and dignified way of quelling a choir strike. The boys were disgruntled over their choir treat and there were rumours of a strike. The following Sunday after the morning service the vicar ordered them all back in their places fully robed. "Now you are going to strike, are you?" Sheepish looks from the boys added to his righteous indignation. "To strike? Who are you striking against? Not me. You don't come to the choir to sing to me! You are going to strike against God. Well, anyone who means to strike against God let him leave his seat, lay his surplice on the Altar step, make his reverence to the Altar and go out." Needless to say, no boy moved and no more was heard of the strike.

The rural dean of Gateshead at that time was Moore Ede, another lifelong friend, who years afterwards told Mrs. King that he had one unchangeable rule in his clerical meetings. It was that "No one may speak twice on the same point--not even King."

George and his sister Gertrude had only comfortably dug themselves into that slum parish when the call came for the next stage of the journey.

It was in 1889 that Bishop Lightfoot died. That of course was a sad blow to the whole diocese, but, it fell even more heavily on his beloved "sons of the house." Bishop Westcott preached the funeral sermon and Dr. Hort was also there. This was the first time that George had met him. He often used to say that it is hard to overstate what our Church owes to those three friends and scholars, all truly great men and yet so widely different in greatness. "Bishop Lightfoot," said Westcott once, "differed widely from me in some respects; [8/9] he always was interested in facts and I in principles. And when his facts did not fit my principles I fear I did not think much of his facts."

This section of George King's life may close with some lines he wrote on St. John the Evangelist's Day, 1889.

IN MEMORIAM. J. B. DUNELM.

In silent grief, with scarce a tear;

In faith, hope, love and fervent prayer

Our Father to his grave we bear.Few are our words: the sacred song

Our voices scarce will bear along;

They quiver so with feeling strong.The Fathers of the Church are nigh

To lift the holy prayers on high

To bless the tomb, to breathe the sigh.His lifelong friend and comrade dear

In truth's stern battle, he is here

To cast the dust upon the bier.Disciples, whom his net has caught,

Sons by his bright example taught,

Hither the burden sad have brought.Low lay we him in hallow'd sod

His dust to dust--his soul to God

Has passed, its wondrous new abode.Thanks be to God who gave the Dower

Of Light and Grace and Love and Power,

This last in his triumphant hour.CHAPTER II

A TYNESIDE PARISH IN THE NINETIESChrist to the young man said: "yet one thing more

If thou would'st perfect be;

Sell all thou hast and give it to the poor,

And come and follow Me."Within this Temple Christ again, unseen,

Those sacred words hath said;

And His invisible hands to-day have been

Laid on a young man's head.And evermore beside him on the way

The unseen Christ shall move,

That he may lean upon His arm and say

"Dost Thou, dear Lord, approve?"

LONGFELLOW.

BISHOP WESTCOTT gave the parish of St. Mary's, Tynedock, into the charge of George King in June 1890. It is a large industrial district in the borough of South Shields. It centres round the docks from which it takes its name, and its inhabitants were in those days for the most part workmen in the dockyard, or miners at the neighbouring collieries. There was also a sprinkling of railway men, of skippers and engineers of coal-bearing steamers, and also in the High Street shop-keepers with their shops. Some of the streets were, then, real slums, for there were no parks or recreation grounds as there are now.

The church has no pretensions as a building, but it is spacious and central and now has a vicarage standing [10/11] beside it with a parish hall on the same plot. In the nineties there was a small mission church which has since blossomed out into a parish of its own by the river bank towards South Shields itself. A remark of a parishioner sums up rather aptly the point of view of this really rather remarkable parish, "St. Mary's is neither orthodox nor heterodox but just Tynedocks."

The parish had for its first vicar a man, the Reverend James Jeremy Taylor, who in his earlier days must have done a really fine work on moderate Church lines, but he fell ill and the parish had to be taken over by a curate-in-charge. Mr. Vaughan had with him as fellow curates two men to whom the parish gave their whole hearts, Cecil Boutflower, later to become Bishop of Dorking, then of South Tokyo and finally of Southampton, and Albert Victor Baillie, now Dean of Windsor. These two men were very greatly beloved, and themselves added to the distinctiveness of individuality of a parish which already had "ways of its own."

To quote Bishop King's own words:

"From June, 1890 until Christmas I was alone in the parish excepting for a layman who came to help on Sundays from the University of Durham. My youngest sister, Gertrude, rejoined me in the autumn and we received a very kindly welcome. We did not live in the vicarage which was almost a mile outside the parish and which was occupied by the sick vicar and his wife, but set up house in a small dwelling near the church. At Christmastime of the same year, through the kind offices of Cecil Boutflower, then Bishop Westcott's chaplain, we got Harold Bilbrough, now Bishop of Newcastle, as a deacon and fellow worker. He, in his turn, became well loved by the people and brought with him many excellent gifts [11/12] and was an untiring worker."Towards the end of 1890 we began our first great task, the building of a large parish hall to which we gave the name now held by the very distinguished building in Wesminster of 'Church House.' Building was cheap in those days and £1,200 gave us a large plain hall capable of holding three hundred and fifty people, three class rooms, one of which was a most commodious stage, and a most useful upper room, made sound proof, and accommodating seventy people."

All through the busy, humdrum days the rule of study, prayer and reading formed at Auckland Castle continued to be kept; small handbooks or textbooks on subjects were studiously avoided, and only first-class books were considered to be worth the trouble of tackling. About this time King joined the English Church Union, though he never attended the meetings. It was one of the Lightfoot traditions that Church societies of a controversial character were undesirable, but to King the E.C.U. was an exception. It was the time of the trial of Edward King and the Lincoln Judgment, and while that uncertainty lasted he was profoundly anxious about his own position in the Church of England. He was always opposed to Erastianism and a state governed Church, and he never changed his viewpoint. The judgment came to him, as to many, as a welcome surprise, for it seemed that after all the Church of England was not to be ruled by any but its spiritual leaders.

King's sermons were always carefully prepared, and they grew in depth at this time. They were never emotional, but addressed to reason, imagination and conscience, and they were certainly listened to with attention. He himself has said, "I used to preach mainly [12/13] on faith and morals; my sermons were written out in full and the matter but not the words delivered extempore from short notes. On rare occasions I must have been somewhat dramatic, and profited from the good-natured chaff of one of my colleagues who told me that if I again made David come up into the pulpit to discuss with me the fifty-first psalm he would scream. But, thank God, there was a message and it grew in force and clarity."

At the close of his life Bishop King would pass on to young priests three lessons which he said had stood him in good stead:

1. That an appeal to the emotions is wrong unless reason has been previously convinced.

2. That a true sermon is a message from God and not from oneself.

3. That a sermon must be practical, and aim at helping people to live as Christian men during the ensuing week.Baptism at St. Mary's was always administered after Evensong on Wednesday evenings, and at one time there were so many that the service became rather long. King consulted Bishop Westcott as to whether Evensong might be shortened, to which the gentle Bishop replied, "Would it not be wiser to shorten the address rather than the service?"

Once a week King gave an address to the trimmers in the dockyard during their breakfast hour in one of the cabins. This was much appreciated by them and the discussions ranged from Froude on "The British workman in the time of Henry VIII," to "Why so many workmen do not go to church."

In 1891 the staff was augmented by [13/14] the Reverend A. G. B. West, now so well known for his work in St. Dunstan's in the East, and the Fairbridge Farm Schools. He brought with him a forceful personality, much energy and a special capacity for dealing with rough workmen, and from the first he was an able preacher. He was not a conventional curate at all, but added his quota to the originality of a parish which has already been shown to have idiosyncrasies of its own.

The rural dean for most of this time was Canon H. E. Savage, then vicar of St. Hilda's, South Shields, afterwards Dean of Lichfield, and his personal friendship and wise counsel were always at their disposal. He and his sister also did much to help in the social side of life on the Tyneside. Canon Savage having been chaplain to Bishop Lightfoot was also joined in that inner circle which meant so much to each member of it.

At the end of 1893 the vicar of St. Mary's died and early in 1894 the dean and chapter of Durham offered the living to George King. This offer was the occasion of an amusing episode, and as all connected with it are long since dead, it is worth telling now, as it casts a sidelight on the life of such bodies which any who know about them will appreciate.

The Durham Chapter was somewhat sharply divided in churchmanship and three of the canons were opposed to the nomination of George King to the living of St. Mary's, Tynedock, considering him to be too "high church"; also the fact that he was a Cambridge man went against him as the three opposing canons had a B.D. of Durham in the running for it. Finally King had not gone round, hat in hand, to solicit the canons personally, nor had he applied for it as was the wont in those days. He never in his life applied for any spiritual [14/15] office, such a practice being against his conscience. The kind archdeacon secured the necessary letters for him, including a strong one from the bishop of the diocese, which in itself did nothing to increase his prestige, deans and chapters being proverbially touchy at any "interference" by the bishop.

Anyhow there was the battle set in array. The dean, a sick man, was wintering in the south when one day one of the "reluctant" canons met Canon Body, who was greatly needing a rest before his Lent work, and urged him to go abroad assuring him that "all would go as he wished about the Tynedock appointment." But sad to relate as the day drew near the archdeacon began to grow suspicious, and at last he telegraphed Canon Body to return. The rest is best told in Canon Body's own words: "I reached Durham at midnight, and gave strict orders to my household that my return was to be kept secret, and then quite unexpectedly I walked into the chapter just as the vexed question of Tynedock came up. I consider the long and wearisome journey from Florence was more than worthwhile just to see Canon's face when I opened the door."

The decision was postponed that day as, without the dean, the chapter was three against three. But rather than drag the dean up to give the casting vote the canons gave in and the living was given to the man who had worked so faithfully there as priest-in-charge. It is nice to think that the same Canon--bore him no grudge but came out to preach the next Harvest Festival sermon.

When King became vicar he was able to take another curate on to the staff and in 1894 yet another Auckland Brother, the Reverend Alec Ramsbotham, and his sister joined them. Margaret Ramsbotham, true to the [15/16] tradition of sisters in the diocese, became a most indefatigable and capable voluntary worker.

In this same year the parish prepared for a parochial mission which was to be conducted by Father Dolling of Landport and his great friend Charles Osborne of Wailsend. The preparations were all made, the posters and handbills all out with the Missioners' names on them when, on the day after Christmas, only a few weeks before the opening of the mission, a letter was received from the great Bishop Westcott saying in the kindest possible way that he could not authorize Father Dolling to the diocese, because he was having differences of opinion with his own bishop in the Winchester diocese over an altar used for masses for the departed. The Bishop of Winchester was Dr. Randall Davidson, another of the greatest of bishops. This was, indeed, a bombshell, and it caused the greatest consternation. King went off to Canon Body at once who told him he must obey his bishop if he wished for God's blessing on the mission, and then most generously offered, if the mission could be postponed for two weeks, to come and preach it himself. There was no other course to take, but it was only years afterwards that King realized how much pain the decision inflicted on Dolling himself. What hurt him specially was that Dr. Westcott, whom he so much honoured for his social work, refused to trust him to preach this mission. However the mission took place under Canon Body, assisted by the Reverend Wilfred Gore-Browne, afterwards Bishop of Kimberley and Kuruman, and the Reverend Charles Fitzgerald, afterwards a Mirfield Father.

The great and permanent outcome of it was the recovering of the Church Schools which had been leased [16/17] for twenty years to the School Board of that day. The lease having expired, greatly daring, the clergy of St. Mary's decided to give the School Board notice and to reopen as Church Schools, which they remain to this day. Only two other schools in the country have thus been recovered for the Church. The real hero of this episode was a young married man, John Grayson, who in spite of the croakings of his friends dared greatly and threw himself into making a good job of it. This he did with unqualified success, for the school started, in spite of strong opposition, with a hundred and thirty children at the opening, and rose to two hundred the same afternoon, and by the end of the year it had reached its full complement of four hundred and fifty, and a year later it was receiving its full government grant.

The parish of St. Mary's was delightfully friendly, and full of loyal souls. There was the old churchwarden who, when walking with the local Baptist Minister, paused to turn into the church; he was greeted by his companion in horrified tones, "You surely don't go there, do you?" "Yes, I do" was his reply. "Why, your vicar is leading you to Rome." "That he is not," said the churchwarden, and with true north country independence added, "and if he were, I would not follow him." "Well, does he ever say a good word for Crammer, Hooper and Latimer?" probed the Baptist. Now the churchwarden was somewhat vague as to the history of those divines, but sure of his vicar he loyally replied, "No, I can't say that he does; but he certainly never says anything against them."

Parish life in the nineties was so very different from the fourth decade of this century. [17/18] There were no "Pictures" to take people from their homes, and few labour saving devices to ease their toil. There were no Women's Institutes or Boy Scouts or Girl Guides which are of such value now. In consequence the clubs and guilds and social amenities provided by the parish church had but few rivals.

In 1897 Harold Bilbrough went to be vicar of St. John's, Darlington, and Alec Ramsbotham to St. Alden's, Gateshead. During his last years in the parish King had as curates Herbert Fleming who later became an army chaplain, and Morris Hodson who stayed on for a while with the next vicar, and then went to be succentor in Leeds Parish Church, and who after being Archdeacon of Durban for some years returned in 1926 to do a fine piece of work at East Ham.

St. Mary's, Tynedock, boasts of having given five Fathers-in-God to the Church. George Lanchester King was the first to be called to the episcopate in 1899. He was followed by Cecil Boutflower in 1905, Harold Bilbrough in 1916, John Daly in 1935, Philip N. W. Strong in 1936.

CHAPTER III

THE HIDDEN LIFE OF THE SOUL"Strive not so much to do but learn to be,

That God Himself may do His will through thee;

Better it is for thee to please Him so,

Than by such ceaseless running to and fro

On errands which thine own blind heart hath planned.

Better to lay in His thy restless hand,

And let Him choose thy task."DURING the years of his ministry at Tynedock George King's hidden, secret life of the soul grew and deepened. He had begun to use the Sacrament of Penance before he left Holy Trinity, Gateshead and, as is so often the case, this led him to a more thorough and systematic use of daily meditation, an important and difficult exercise. His choice of books was very much what any parish priest taking his work seriously would choose. Matins was always at 7.30 a.m., so he rose early, a habit he retained to the end of his life.

At Cambridge he had read for a classical and not a theological tripos, so he did not exactly start with the same grounding as many of his friends. Church history always interested him, and he early began to be attracted to the Greek Liturgies. He read of course Lightfoot and Westcott, Hooker and Butler and F. D. Maurice. With Maurice he had been acquainted since boyhood for their rector at Great Barton was a disciple of his and had himself been curate to Charles Kingsley. Indeed there is a story in the family of one famous Sunday when the great Maurice was to preach at Barton Church their [19/20] mother firmly ordered the carriage and had the whole family then at home driven down to St. James's, Bury, rather than allow them to sit under a man whom she felt was "not sound" in the faith!

Lux Mundi came out about this period and played a large part in King's life, and he found all the intellectual help that he needed in the writings of Charles Gore and his school of liberal Catholics. Gore's book on the Ministry, confirmed later by Hamilton's People of God, and his Bampton Lectures met his need as to fundamental truth. SS. Augustine, Athanasius, Anselm and Bernard all figured in his reading then.

His interests widened considerably between 1889 and 1899. Strenuous work in a large industrial parish cannot leave a man as it finds him. The young clergy of those days in the diocese of Durham had been shown high ideals, and though they continually fell short of them they tried to realize them. Underneath the moving currents of an active and laborious life there was the silent flow of the hidden tide, and spiritual powers were developing. There was, though he knew it not, a divine preparation for his later life.

But once again it was his contact with men that played the greatest part in his life. He formed many and valuable friendships, notably with the Reverend John Lister, his first confessor and a strong fighting Catholic. Also with the Reverend Walter Holmes, now a member of the Oxford Mission to Calcutta. King and Holmes eventually broke away from Canon Body's helpful retreats in Durham and fell under the spell of Mr. Gray of Helmsley, and were later, under the influence of the late Father Cyril Bickersteth, drawn to the Mirfield Brotherhood.

[21] They were admitted on the same day to the Society (not the Community) of the Resurrection, and attended annual retreats and meetings of the order at Mirfield. Members of the Society renewed their pledge of celibacy each year and were bound to at least four meditations of half an hour each every week and also two at least of the offices of the Hours. He was often welcomed at Mirfield and only resigned his membership in 1920 when he returned from the mission field. The fact that he did not ask to test his vocation at Mirfield in those early days was due to his belief that parochial work was what was needed most, and he was entirely immersed in the work and interests of his parish so, hardly knowing that he did so, he made the important decision to carry on as a parish priest. But those wonderful retreats made in common with a group of fellow clergy all in deadly earnest, under such men as Charles Gore, Vincent S. S. Coles and Walter Frere were a priceless help and satisfaction. As he once put it himself, "Spiritual things happened to us there to which we hardly liked to allude and found impossible to describe, and the retreat was always followed by a day for the annual meeting of the Society, which in those early days before the College was completed was not large in numbers. I was always welcomed at Mirfield on my return from my missionary diocese and found ever there the same spirit of love and prayer combined with an atmosphere intellectual and bracing. Thank God for Mirfield!"

The beloved St. Peter's Day Auckland gatherings went on each year under Dr. Westcott whose addresses, so different from Lightfoot's as they were, served like them to widen and deepen the spirit within them.

But there was one experience at this period which [21/22] stood out as a landmark. In 1895 some seven or eight of them, all friends together, met at the instigation of C. H. Boutflower, then chaplain to Bishop Westcott, in St. Peter's, Jarrow, where George Halford was vicar, to consider carefully whether or not they were called to work for the Church overseas. The day started with the Eucharist, and after breakfast they settled down to a time of prayer and conference. King, as one of the seniors, was asked to introduce the subject. They were all unmarried and were there not to face the question "Shall I go abroad if called?" but the far more searching one of "Is there anything to prevent me from offering to go abroad?" They all spoke quite simply before one another and before God: one said, "I am quite ready to go later on, but at the moment I have, as the eldest son, some family business at home." Others said, "We will go if asked, but we are very happy where we are." It was unanimously agreed that Boutflower, the keenest of them all, must stay where he was as Bishop's chaplain.

The immediate outcome of the meeting was that a letter was written to Bishop Westcott, the gist of which was, "We are free and willing to go abroad if called by authority to do so, but we do not think that in this matter we should act on our own initiative; we are men under authority." This was signed by four of them for the whole party. The ultimate outcome was that in 1897 George Halford went to Australia to start a missionary Bush Brotherhood and afterwards became Bishop of Rockhampton and is still working out there though he has resigned his See. In 1897 also Oswald Parry joined the Archbishops' Assyrian Mission, and in 1921 after a spell in East London became Bishop of Guiana. [22/23] In 1899 George King went to Madagascar as Bishop. In 1902 E. F. Every went to South America and became Bishop of the Falkland Islands. Walter Holmes went out to the Oxford Mission to Calcutta. Cecil Boutflower in 1909 resigned his suffragan Bishopric of Dorking to go out to Tokyo as Bishop, and Ernest Foster went out to be Dean of Hobart.

They were all true to their letter to the bishop. Several of them received invitations to go overseas, but on referring them to Dr. Westcott in some cases he counselled them to remain at their post for the moment. There is a letter extant from King to C. H. Boutflower, dated February 19th, 1896, "I cannot send my note to the bishop without telling you how much I owe to your help and encouragement and example. I have simply said that I put myself unreservedly into his hands for Home, or India, or the Colonies. I am quite clear as to my duty so far: for the rest let him decide."

Some words of the Reverend Father R. H. A. Steuart, seem to sum up this part of the journey of life; "When we look back in vain over our lives for anything to our credit that was wholly good or true or fine, seeing nothing there that we should not dare to offer to God, but only wasted graces and lost opportunities and cowardice and selfishness and untruthfulness and infidelity and

all manner of wrongness: then is the moment to think of Christ and to put Him before ourselves . . . remembering the Magdalen and the Prodigal Son and the adulteress in the Temple and the good thief on Calvary."CHAPTER IV

MADAGASCAR"Converting men is God's work; Evangelizing them,

that is presenting the Gospel to them, is ours." EUGENE STOCK.FROM the time of the memorable day of prayer in Jarrow Church in 1895 until early in 1899 George King worked on happily and energetically in his parish in Tynedock, content to leave his future where he had placed it in the hand of God.

Then on February 13th he received, completely out of the blue, the following characteristic letter on half a sheet of notepaper from Frederick Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury: "My dear Sir, Are you willing to undertake the Bishopric of Madagascar? It is very difficult, I fear, but from what I hear of you I believe you would do the work well. You can get all needful particulars from Prebendary Tucker (at S.P.G.). Yours faithfully, F. Cantuar."

This fateful letter reached him on Monday afternoon just before Lent, and was, in his own words, "a devastating surprise." He had had no premonition, no one had sounded him on the subject. Save for Bishop Westcott and a few close friends no one knew that he was willing to go abroad. Above all it caught him in the midst of engrossing and contented parish work. Naturally he dropped on his knees in prayer and also naturally, knowing the man and his simple, steadfast trust in divine guidance, his decision, as far as he himself went, was made within a few hours.

[25] A few days later he presented himself at the S.P.G. House in Delahay Street for an interview with Prebendary Tucker, then secretary of the venerable Society. After a kindly and sympathetic interview the young priest was sent over to Lambeth Palace. His thoughts must have reverted to that other time when in 1884 he walked across Lambeth Bridge to meet for the first time his great Father-in-God, Bishop Lightfoot; and he must have thanked God for all that had followed that interview.

He found the great Archbishop with a pile of letters and a very large cup of tea before him. He had not met him before, but was tremendously struck with his calm strength and restrained spiritual fire. After a few kind words about the office and task before him, and its very special difficulties, the Archbishop asked him about the stipend, and when told it was £300 he said doubtfully that it was "not very much," to which King replied he was unmarried and would make it do.

After more interviews at the S.P.G. and a visit to the doctor, who pronounced him fit, he returned to his parish. Bishop Westcott warmly approved of his accepting the call, and Canon Body and others sent him the most affectionate letters full of love and encouragement.

Bishop Robert Kestell-Cornish, who had been Bishop in Madagascar until three years previously, also wrote most warmly and invited him to his parish in Devon before he sailed. He needed all the encouragement he could get for though he had no doubt as to the clearness of the call, yet he was leaving a great deal behind him. In the first place he was leaving his sister Gertrude who had shared his life and work in Tudhoe Grange, Gateshead and Tynedock for fourteen years. [25/26] He was leaving his beloved parish which held within it so many real friends and he was leaving his well beloved diocese of Durham with all its sacred memories. He was leaving too his parents who were growing old, and his home to which he was devoted.

His last official Sunday at St. Mary's fell on the fourth Sunday after Easter. He was consecrated at St. Paul's Cathedral on St. Peter's Day, 1899, with Bishop Whitehead (Madras) and Bishop Peel (Mombasa). Charles Gore preached the sermon and Bishop Westcott and Bishop Kestell-Cornish presented him to the Archbishop.

The annual Auckland Brotherhood gathering was held in London that year. Dr. Westcott entertained them at luncheon in a City Company's Hall; the afternoon was spent at Westminster Deanery where Armitage Robinson was dean, and Bishop Westcott gave his address at St. Margaret's, Westminster at 6 p.m. The day had its heartaches and its joys and ended for the newly consecrated bishop with a family dinner party at an aunt's house in Philbeach Gardens.

Lord Salisbury, then Foreign Secretary, gave the young bishop a kindly send off, though he told him he would find the French very difficult, and added with kindly but caustic humour that he would be "like St. Paul under Nero."

The following week Bishop King started with Harold Blair, a young priest, and Allan Neil Webster, then a layman desiring ordination, for Paris, Marseilles and Madagascar. On their arrival at Paris they called on the Ambassador, Sir Edmund Monson, and found an invitation to a reception awaiting them. The bishop was presented to a Grand Duchess who filled him with [26/27] confusion by asking him if he knew all our Royalties with whom she herself was intimate, and then proceeded to tell him that she was "High Church" and asked did he "teach confession"? He stammered out some sort of suitable reply and tried to retire to less august society as soon as politeness permitted, feeling much relieved to think there would be no Grand Duchesses in Madagascar.

They joined the boat at Marseilles two days later, and, in order to economize mission funds, travelled second class, which as the bishop afterwards allowed might have been truly apostolic but was unwise, so he did not do it again.

People often ask why English missions are established in Madagascar which is a French island. It is worth while making the reason clear before continuing the story.

Madagascar became a French colony in 1896. But British Missions had already started effective evangelization and were strongly entrenched long before the French occupation. Before the French took over the island it was ruled by a Queen and her Prime Minister. In the thirties and forties of the century a good start was made by the London Missionary Society, a congregational body, but fierce persecution broke out and the missionaries were compelled to leave. The native converts suffered severely and many were martyred. The story, which is well known, witnesses to the sterling qualities of the people. In 1860 a complete change of policy took place, and the London Mission returned to find many of their converts faithful and ready to welcome them. In 1864 the Anglican Church sent its first missionaries. They were followed by [27/28] the Friends' Foreign Missionary Association, and later still came a large Norwegian Lutheran Mission. Robert Kestell-Cornish went out as the first Anglican Bishop in 1874. He built a large stone cathedral in the capital, Tananarive, dedicating it to St. Lawrence, and the work of the Mission grew and spread.

When Bishop King reached Madagascar he was met at the coast by Frank Gregory (son of the Dean of St. Paul's) who remained a valued friend to the end of his life, though he left the island after a few years and went on to Mauritius where he became bishop.

Relations with the French were somewhat strained in 1899. The "Fashoda Incident" was very new, and the "Entente Cordiale" had not come into being. The Boer War was in progress, so altogether English stock was rather low. However Lord Salisbury's gloomy forecasts about "St. Paul under Nero" only came true some years later.

The new bishop was given a warm welcome by the authorities and soon set himself to work to become bilingual. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays he spent the mornings studying French with a French sergeant, who soon became the best informed member of his regiment in the progress of the Boer War, through the translation of the Reuter Telegrams and The Times' leading articles. On Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays he learnt Malagasy from one of his priests.

General Gallieni was Governor-General of the island and most cordial relations existed between him and the Mission. A convention had been negotiated between him and Bishop Kestell-Cornish by which the Mission conceded some valuable house property in Tananarive in return for a written assurance that all other property [28/29] in churches, houses and schools in the colony should be secure. This convention proved to be a sheet anchor in the difficult days that were to follow.

Life in the island has changed very considerably in the last forty years, and the greatest changes have been effected since Bishop King left in 1919. In his day there were but few railways, and trains only went two or three times a week. The roads were poor and motors were unknown. Most of the journeys were made on horseback or in filanzana (palanquin) through the forests, or in canoes on the coast. In a letter to his mother after owning that he had had a nasty bout of fever, the bishop writes:

"I start off next week on tour, being away from home for some weeks. I shall take a filanzana. I had intended to ride my pony but I am afraid of the fatigue. I often wonder if we grow soft in Madagascar or only wise. On the one hand it is far more manly and economical to ride, on the other hand I can't work if I don't keep well."

To his great joy after he had been working there alone for a year his sister Gertrude went out to join him and to keep house for him in the capital. Thus the happy intercourse in the north of England grew and flourished once more in the mission field.

A circular letter written to some of the Auckland Brotherhood gives a good deal of local colour and is worth quoting here:

La Mission Anglicane,

Tananarive, Madagascar.

March 27th, 1900.My dear Mac,

I'm not sure if a circular letter system is good for you men at home. I am sure it is good for me and [29/30] others like me abroad. I write a letter which goes the round--one letter--and I get the thoughts, and I trust the prayers, of all who read.

It is very strange to find myself in the thick of confirmation work, under such very much changed conditions. A year ago it was a class of English boys and girls, now they are brown and black. So different, too, inside them, and a very real anxiety as to morals. However, the Christian life meets all needs, and many appear to me to be very really in earnest. Also they are as sharp, so far as I can judge, as an average north country class. My principle deacon is ill just now, so that the whole of such teaching falls to me. I think they understand my Malagasy, I stop continually to ask if things are plain.

It is simple, blank fundamentals that we need--Sin and Repentance and Pardon and Grace. Page always said I was an evangelical and I believe I am, tho' I don't grow any more in love with what is distinctively Protestant and of the 16th century.

My Lent work must be very much like your own, I should fancy. I give an instruction to communicants at 5 p.m. each Wednesday in the Cathedral. I have a confirmation class on Tuesdays at 3 p.m. and I give my Wednesday instruction a second time in a church in the eastern district (2 ¾ hours' ride out and the same back again) every Thursday at 9.30 p.m.

We have lately opened the south transept of our nice cathedral as a chapel for classes, instructions, and weekday celebrations. It is very nice--the Altar is of dark wood with blue painted panels and a little black and gold to brighten it up.

The French are going to make next Sunday hideous by organizing a great children's Fête. All children are to assemble at 9 a.m. and march under banners without any distinction of school or denomination. [30/31] They get buns given them at 12. I have a note from the Commandant of the district asking us to aid in this festival. I am simply acknowledging his letter and doing nothing whatever. But I am afraid it will go far to spoil our Sunday.

The authorities are, however, friendly on the whole. It is a lucky thing for us that we are Anglican--not the English Mission--the L.M.S. is called "English." The view taken by the French is, I find, that there are two churches in England--the Haute Eglise and the Basse Eglise. The Anglicans are the former and the ways and doings of the L.M.S. are those of the latter.

There is much more direct discouragement of our Mission on the coast, than here. They cannot understand that we are not politicians, and I suppose they think that the English Fleet is always ready to pounce on Madagascar. If they could only understand the utter worthlessness of Madagascar to England it would be better for our work and for their nerves.

Give my love to all the Brethren. I hope you are well and that St. Hilda's goes ahead.

Yours very sincerely and affectionately,

George Lanchester King,

Anglican Bishop.This Memoir does not set out to be in any sense a "life," telling all that befell him. It is only intended to deal with the various events which deepened his life and strengthened the message given him by God.

There were many and interesting adventurous journeys, long and intricate dealings with his flock who found him a true father-in-God, pleasant contacts with French officials, and missionaries from other societies, and friendships which lasted a lifetime with many people.

[32] In visiting his scattered churches the one message he never failed to drive home was that each little collection of the faithful in any given place was the Body of Christ, the Church of the Living God in that place. If that Body of Christ grew cold or was unfaithful the whole Body of Christ suffered. His successor, Bishop Ronald O'Ferrall, wrote of him after his death: "His greatest work was the care of his spiritual children, the Malagasy clergy. His own deep convictions and devotion to our Lord made him an ideal father-in-God both to them and all the churches he visited with indefatigable vigour."

CHAPTER V

MADAGASCAR YEARS OF TRIAL"Whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth . . . if ye endure chastening,

God dealeth with you as with sons?'

HEBREWS xii. 6, 7.WE now come to the period of the bishop's life in the island when the words of Lord Salisbury to him camp truer than possibly that august statesman ever dreamed would be likely. "You will be like St. Paul under Nero." In July 1906 the bishop wrote home to his mother, "I have spent the whole morning in trying to organize a School Defence Association out here. There is no doubt that we have a Governor-General who is opposed out and out to Christianity and Missions. The colony is too poor to take over the education altogether into schools of its own, and it is trying to make us go on paying our qualified mission teachers, while they take over the practical management of our work. Naturally we do not see the force of this. Also there are signs that our ordinary missionary work is going to be interfered with. However, if I can get the missionaries of the London Mission and others to see as I do, we shall protest and refuse to be made tools of; the Church of Christ versus the world, and it is the Church which ought to be always the attacking party."

General Gallieni had by 1906 been recalled to France and his place was taken by Monsieur Augagneur, an [33/34] avowed enemy of all Christian Missions, French as well as others. At Bishop King's instigation all the Missions (with the exception of the Roman Catholics) acted together in things political and educational, and consulted carefully the newly arrived French Protestant Mission. Mr. Porter, the British Consul, a close friend of the bishop, gave his support most ungrudgingly. When on tour the bishop was always most punctilious in calling on the local administrators and chefs des provences and as a rule found them friendly and even cordial. All the missionaries in the capital were careful to appear at official receptions on New Year's Day and July 14th, and did all in their power to show that they were obedient and loyal to those who ruled over them.

Augagneur, with one stroke of his pen, refused to allow a building to be used for education which was also in use as a place of worship, as was usual in small villages. He suppressed village schools by the hundred, and the few that were preserved were harried and discouraged by local authorities. He also promulgated the dictum "that no one may come between the administration and the administratees" which was a most embarrassing rule to apply. It meant that there could be no English head of a school, and unless he held a French certificate he could not teach.

Augagneur also refused to allow any new churches to be built and no gatherings for worship might be held in private dwellings; he also decreed that as few as six persons constituted an unlawful assembly; he would recognize no church that had not a written authorization, and this wrought havoc in the many outlying districts where permission had been given verbally by the local French administrator in early days. Those churches were [34/35] all summarily closed down, and it was made a punishable offence to meet in one of them; he demanded at least sixty signatures to any petition by a village for a new church before he would even consider it.

From all this it will be seen that the spread of the Kingdom of God was most seriously held up, and the Governor-General held all in the palm of his hand as there was no code or regulations of public worship in Madagascar. The kindliness of local administrators occasionally mitigated these severities, but as a rule they were enforced. One of the teachers was put in prison for acting as secretary to a village which presented a petition for a church, another was fined and made to do forced labour on the roads for opening a closed church on Christmas Day. The Christians had stormed the church, forced it open and were enjoying themselves singing the Christmas hymns when, as ill luck would have it, the "chief of the province" rode by with disastrous results.

During this period Bishop King found time to do a good deal of literary work in the vernacular, and his commentary on the Book of Revelation was the "best seller" of its time. The French never could understand why this was so, but the Malagasy were clever enough to read into the carefully described "Roman Government" much that was happening to themselves at the moment and, like the early Christians of St. John's day, they lifted up their hearts and took courage.

At the death of King Edward, when the French were inclined to be anxious as to the future of the Entente Cordiale, Archbishop Davidson with no word from anyone, but with his wonderful touch on the pulse of the whole Anglican Communion, took the trouble to go off [35/36] to Sir Edward Grey in the Foreign Office and suggest that it would be a good moment for the French government to send a more reasonable Governor-General to Madagascar. The diplomatic hint was received and acted upon, and with Monsieur Picquie in 1911 came a more hopeful period in the history of the Mission.

In 1908 it was learnt by chance in Tananarive that there was a draft of a code to regulate public worship. It was to be a decree by the colonial office which corresponds to what we would call in a British Colony "an order in Council." The missionaries had none of them been consulted, and it was essential that they should know the terms of the code which they would have to administer. Bishop King was shortly returning to England for the Pan-Anglican and the Lambeth Conferences and felt he must in some way get to know what was in the proposed draft. The French Protestant Mission in Tananarive procured a copy of the projet; how this was done was not asked and was veiled in mystery, but it was brought to the bishop "for one night only." He sat up all night and copied it in full, thinking that it might be useful, as indeed it proved. The three British Missions (the S.PG., the London Missionary Society and the Friends' Foreign Missions Association) had agreed to appoint a distinguished lawyer, Sir Thomas Barclay, to act for them with the Paris Mission and negotiate on their behalf. It was also agreed that Bishop King should meet Sir Thomas Barclay in Paris and provide the local colour and details which the case required.

So in February 1908 he and Sir Thomas met in their hotel in Paris and were later joined by the Secretaries of the French Protestant Mission and a Monsieur Siegfried, a Senator, who had agreed to act as intermediary [36/37] with the Secretary for the Colonies. His first question was, did anyone know the terms of the projected draft, and quite a sensation was caused when Bishop King replied that he did, and produced the secret copy. The old Senator bustled off with it and secured an official draft which only differed in a few minor points. It was gone through clause by clause and the bishop was able to point out some parts which could be improved, but on the whole, it seemed a fair code. It conceded the important point of allowing, with certain official safeguards, religious meetings in a village house where there was no church. On the other hand no new church could be asked for if, within a radius of ten miles, there already existed four churches of some kind or another. In view of the many denominations existing in the island this was a hardship.

Over luncheon the bishop and Sir Thomas agreed that in their formal visit to the Minister for the Colonies, ostensibly to thank him, if they were asked were they entirely satisfied they would try for a concession on this point. In due course at the interview the question was asked and the bishop pleaded that the four churches in a given radius might be changed to five. He added he was not there as a negotiator but merely as an onlooker, to which the Minister replied that as such he was très bien documenté and that the request would be carefully considered. The bishop said it would be regarded in Madagascar as a most valuable concession and that he was sure they would be able to make it work smoothly. The point was gained and they bowed themselves out. It is interesting to note that the Minister for the Colonies of that day was Monsieur Dumergue of fame in later days, and that Sir Thomas Barclay died about four days after Bishop King in 1941.

[38] Since then relations with the French in Madagascar have steadily improved. The 1914-18 War helped in this very much, and they continued to improve under Bishop King's two successors Bishop George Kestell-Cornish and Bishop Ronald O'Ferrall.

What they will be for Bishop Vernon when he reaches the island and it is once more in touch with the rest of the world God alone can tell. The native Church is in His hands and the work grows and deepens. Truly one sows and another reaps but God giveth the increase.

CHAPTER VI

MADAGASCAR

THE BUILDING UP OF THE CHURCHBISHOP KING was a wise and true father-in-God to his flock, but the Madagascar Mission is so seldom in the public eye that it is little known on how wise lines it has been reared from the very first. When Bishop King arrived in 1899 the Church had been for three years without a bishop, so there was much to claim his attention. Each year he had to make seven tours to visit the various church centres. Three of these were in the central plateau and four along the coast. The real interest and charm of a missionary's life is found in his evangelistic and pastoral work. He is always dealing directly with souls. He preaches the Word to those who need it, he administers the Sacraments, encourages and disciplines the faithful, his financial work is to promote the self-support of the people. These tasks involve considerable fatigue and some measure of discomfort.

In Madagascar the missionary led a simple life, ate native food, slept, while travelling, on a stretcher in a native hut where his boy spread a clean mat for him, heard the cocks crow and the geese cackle when he rose in the morning. There were mosquitoes and other pests to fight, and an eye to be kept for beetles, rats and an occasional centipede. On retiring at night he would be wise to hang his boots well out of reach of snakes and beetles. He had to carry his own provisions in his party, [39/40] and his native cook prepared his meals for him on arrival at his destination, where the elders of the village would visit him with a gift of a chicken or some eggs or rice. Hospitality towards strangers is deeply rooted in the character of the people, heathen or Christian alike.

Madagascar is a malarial country which means that the European has to avoid undue fatigue and long walks. This compelled him in those days to use either a palanquin or filanzana, a canoe (on the coast) or a pony. In these days, of course, transport is entirely changed and motor roads intersect the country and the train service is greatly improved.

The bishop in visiting the various churches scattered up and down his huge diocese would generally arrive before sundown and at once hold a service, giving an address in preparation for the Eucharist next day. Baptisms were taken and Confessions heard if there was not a resident priest. Next morning early Matins would be said followed by the Confirmation Service. The Holy Communion was then celebrated and after a communal breakfast a friendly talk with all the church folk followed, lasting about an hour, after which the journey continued to the next halt.

The Ecclesia Malagasy aimed at securing discipline in the people rather than numbers and it was a well ordered and well instructed body. The Book of Common Prayer had been translated into the vernacular, the only very notable difference being that they had adopted the Scotch office for the Holy Communion as Bishop Robert Kestell-Cornish, the first bishop, had been consecrated in Scotland. The members of the Ecclesia Malagasy knew what they stood for in doctrine and discipline and worship, and though they were far behind the other churches [40/41] in numbers they counted for a great deal more than the statistics would lead one to suppose, and the influence was out of all proportion to the numbers.

In 1908 when the Augagneur regime was at the height of its unpleasantness Bishop King received a letter offering him the Bishopric of Northern Rhodesia. It must have been a very tempting prospect, but never for one moment did his allegiance to the Church in Madagascar waver. Like John Fisher of Rochester he might have said he "would not leave his poor old wife to marry the richest widow . . ." He may also have felt like his Lord that there was no short cut or easy way out of the difficulties that faced him.

In 1910 a most interesting and romantic adventure befell him which he has described in a little book published by the S.P.G. called The Self-made Bishop. It must however be mentioned here. It reads like a vignette from the first century of Christianity, and had it been handled with less skill, tact and statesmanship it might easily have led to another schism.

In 1885, the French occupied the port and district of Diego Suarez which was thus completely cut off from the rest of the island which was still ruled by its native queen. In this district, covering some 300 square miles, a certain native Anglican lay reader named John Ratisischena set himself up, without any authority whatsoever, as a bishop. He only knew that he and his people were Anglicans, that the missionaries had had to go and leave them alone, that the Anglican Church must have bishops so he decided to become one, and told them he would thank them to call him "The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of the North, D.D." His wife cut out and made him the best D.D. hood that she could contrive from [41/42] memory and a piece of red material, and "Bishop" John ruled his flock with firmness and wisdom. He evangelized with real apostolic zeal and fervour, founded village churches, and ordained deacons and priests. He knew a church had to be consecrated but he searched his Prayer Book in vain. At last he decided that a new church must be baptized and so he used the baptismal service, tracing the sign of the Cross on the floor in water.

By 1910 he had grown old and feeble and at the request of certain delegates from his flock the bishop went to visit them. He had never heard of their existence, communications were difficult from that district, but he was met by the delegates and after many adventures in a catamaran he met the old man and found himself at the end of an imposing procession of deacons and priests (all correctly habited) none of whom he had ordained!

The bishop decided nothing could be done in-a hurry, so he left them to carry on as they were for one more year, but in 1911 when he visited them again two of their leaders returned to Tananarive where they were prepared for Holy Orders and in time were ordained. On their return to the North "Bishop" John's priests ceased to officiate, except as lay catechists.

The history of this church has been one of steady and sustained progress. From the first they were self-supporting, and were a singularly simple-hearted set of people, who neither asked for nor expected a share in the S.P.G. grant except for the school.

In his twenty years in Madagascar Bishop King only came home three times, once in 1905 for five months, again in 1908 for the Pan-Anglican and Lambeth Conferences for six months, and in 1913 for seven months. [42/43] His mother had died before he returned in 1913 and his father died just as war was declared in 1914 so that his old home, stored with such precious memories, was broken up and sold while he was still in Madagascar.

The Lambeth Conference of 1908 again produced many new contacts, and friends for him. The American bishops persisted in thinking that he and the Bishop of Lincoln were father and son, as he often armed the saintly old man about, and to many there was a resemblance in the look of spiritual life shining in both faces.

The outcome of the Edinburgh Missionary Conference in 1910 was to help to draw all the missionary societies working in Madagascar closer together. The Anglican Mission did not interchange pulpits, still less did it interchange communicants. The chief difficulty in closer unity with other Missions lay in the fact that they were worked on a congregational basis, so that the local church was supreme in matters of discipline; it chose its pastors and regulated its communicants in contra-distinction to the Anglican method whereby discipline was enforced and moral questions settled by the bishop and his priests. The only other church in the island that shared this distinction was the Norwegian Mission.

A Conference was arranged to take place in Tananarive and Dr. Henry Hodgkin with two others came out to represent the Society of Friends, Mr. Hawkins, chief secretary of the London Missionary Society, with two others and the principal secretary of the Paris Mission formed the delegation. Members of the Norwegian Mission in the south of the island and Bishop King and Archdeacon McMahon completed the number. There were public conferences open to all missionaries, and evening meetings for native workers. The proceedings [43/44] opened with an objection lodged by the local L.M.S. to the inclusion of the Anglican Mission on the ground that there was no interchange of pulpits with them, but this was tactfully dealt with and overruled by the delegates of the Society of Friends.

The two main tasks were to arrange a clear delineation of boundaries for the Missions, to prevent overlapping, and secondly to promote a good understanding. On the last day each Mission, represented by one of its number, spoke frankly on its teaching and polity. By mutual consent Bishop King spoke last, and pressed the value of creeds as the safeguard of religious truth, "which were needed most by those who did not think they needed them." Naturally he was bound to avoid sacraments and their validity as being too controversial, but upon definite creeds he spoke out clearly. By agreement no debate followed. His paper was asked for by the Canadian Board of Missions to be read at a similar gathering in Canada.

To judge by the repercussions in the Church Times and the Christian World of those days the whole Conference attracted a good deal of attention at home. A strong letter to the Christian World from the delegates who were present at the meetings caused that paper to alter its point of view somewhat drastically. The desire to procure more cordial relations between those working out there was most assuredly achieved.

In 1914 the Ecclesia Malagasy had an historic visit from the Archbishop of Cape Town (Dr. Carter) sent to represent the Archbishop of Canterbury at the celebrations of the Jubilee of the Anglican Missions in the Island. The native Christians were almost beside themselves with excitement at seeing for the first time in [44/45] their lives two bishops present together at the same service. But they were somewhat surprised to find that the Archbishop, so superior in ecclesiastical dignity, was smaller in stature than their own bishop. To them this seemed strange and scarcely fitting!

This visit was of immense help to the work of the Mission and the faithful in every village lavished hospitality and honour on the Archbishop. In fact the story went all round South Africa of the delegates from one church who went to greet the Archbishop as he was leaving for the coast to return home and presented him with eight dozen eggs, politely requesting that the baskets might be returned to them at once!

But Bishop King's biggest and most constructive work for the Ecclesia Malagasy was completed only a year before he was recalled home. All his episcopate he had been working towards a properly constituted Church with Synod and Canons of its own. Madagascar had no college for training deacons or priests for Holy Orders. This does not mean no training was given, far from it. Likely men were trained as Catechists, then after five years as such the best were selected and encouraged to read for deacons' orders, under the direction of one of the missionaries. But the diaconate was never a mere probation for the priesthood. The deacon rarely passed into the priesthood in less than five years and in many cases he remained a deacon for life. When selected for the priesthood there would be more study under a missionary and a retreat of five or six days with intensive training, and then ordination. The disadvantages of this method are obvious, but at least the men were approved by long years of actual work and failures were negligible.