RICHARD WILSON

RICHARD WILSON

[123] Dove Row, Gibraltar Walk, Talavera Place, Cat and Mutton Bridge [So called from its proximity to The Cat and Mutton Public-House, Haggerston, on the street-wall of which are two signs bearing the almost incredible verses—Pray, Pussy, do not claw; Because the mutton is so raw. Pray, Pussy, do not tear; Because the mutton is so rare.], Tuilerie Street, Starch Yard, Sweet Lilac Walk, West India Dock Road, Juniper Street, The North-East Passage, Old Gravel Lane, Kent and Essex Yard, Cinnamon Street, Ropemakers’ Fields, Goldsmiths’ Row, Cuba Street, Frying-Pan Alley, Elbow Lane, Maize Row, Cotter’s Green, Flower-and-Dean Street, Folly Wall, Blue Anchor Fields, Three Colt Street, Leman Street, Havanna Street, Drum Yard, Irish Court, Malabar Street, Silver Street, Gold Street, Ion Square, Manilla Street, Cadiz Street, Glasshouse Fields, Tobago Street, Gracie’s Alley [Originally, Grace’s Alley, Well-Close Square, Stepney; all that now marks the site of the Cistercian Abbey of St. Mary of Graces. H. Llewellyn Smith. The History of East London.], Ratcliff Highway, Petticoat Lane, Salmon Lane, Cyprus Street, Globe Road, Shandy Street, Button Street, Russia Lane, Shepherdess Walk, Playhouse Yard, St. Mary Matfelon [Whitechapel Parish Church. Matfel is the Hebrew word for “a woman delivered of a son.”] Toffee-Apples, [123/124] Humbugs, Brandy-snaps, Popcorn, Colt’s-foot, Locusts, Pennyroyal, Saffron, Tansy, Senna, Sarsaparilla, Jellied-eels, Whelks, Saveloys, Hot Dogs, Faggots, Pease-pudding, Broccoli, Eel Pie, Cow Heel, Pigs’ Trotters, Lambs’ Fry, Begels [Bread flavoured with caraway seed and poppy seed], Pretzels, Schtrudel, [A pastry roll of jam, raisins, candied peel.], Peanuts, Cucumbers in white vinegar, Black Pudding, Chewing gum, Sheepsheads—though the days of Walter Besant’s East London are no more.

The first duty of a mother is to “harden” her baby. With this view, Liz was fed, while still a tiny infant, on rusks soaked in warm water, and when she was a year old her mother began to give her scraps of beefsteak, slightly fried, to suck; she also administered fish fried in oil—the incense and fragance of this delicacy fills the whole neighbourhood, and hangs about the streets day and night like a cloud. For drink she gave the baby the water in which whiting had been boiled; this is considered a sovereign specific for building up a child’s constitution. Sometimes, it is true, the treatment leads to unforeseen results. Another child, for instance, about the same age as Liz, and belonging to the same street, was fed by its mother on red herring, and, oddly enough, refused to get any nourishment out of that delightful form of food. They carried it to the Children’s Hospital in Hackney Road, where the doctor said it was being starved to death, and made the most unkind remarks about the mother—most unjust as well, for the poor woman had no other thought or intention than to “harden the inside” of her child, and all the friends and neighbours were called in to prove that plenty of herring had been administered:

[125] Rosh Hashonah (the Jewish New Year, in the middle of September), Yom Kippur, Chanukah (about our Christmas-time), Purim, Pesach, Shevnos, Watch-Night, “please remember the Grotter”:

The Tile-Kiln, The China Ship, The Prospect of Whitby, The Star of the East, The Horse and Leaping-bar, The Bird in Hand, The Bombay Grab, The Old Friends, The Magnet and Dewdrop, The Still and Star, The Bell and Mackerel, The Darby and Joan, The Ben Jonson, The Dean Swift, Paddy’s Goose, The Hoop and Grapes, The Old Mahogany Bar, The Town of Ramsgate:

Pomerantz, Slotski, Frumkin, Yallop, Toporovsky, Winmill, Decent, Eighteen, Skyline, Bluck, Agombar, Suss, Oldschool, Summercorn, Cheek, Stockfish, Ox, Booksneer, Spielsinger, Petrikoski, Filipe, Sugarbroad, Pinkus:

such are some of the street-names, a selection of the commodities that you can buy in those streets, some of the festivals observed, names of public-houses, surnames of inhabitants, in East London to-day. I have been a priest in Haggerston for fifteen years, but for me East London has not yet lost the fascination of its unexpectedness. I found it first through Richard Wilson, vicar of St. Augustine’s Church, Settles Street, Commercial Road, Stebunhithe (alias Stebonheath, Stibenhede, Stebbunhuth, Stevenhethe, Stepney). He was, and is, my other hero.

In one of the eighteen-eighties Harry Wilson exchanged the family-living of peaceful and rural Worton in Oxfordshire for the parish, [125/126] bordered by Commercial Road, which had at the time the reputation of being “the blackest spot in the diocese.” Some three years later he asked his younger brother Dick to leave St. Paul’s, Broke Road, Dalston, [Where the hymn “The Church’s one foundation” was written by S. J. Stone during his vicariate.] and be his curate. The invitation was accepted, and the curacy was filled for fourteen years. Then, at Harry’s resignation Richard became vicar. He remained so for twenty years; when he, in turn, resigned and, once again, became a curate at the same church.

My personal memory of Harry is limited to his splendid laugh, when he sat in an armchair in my home (my father was his cousin), and nursed me on his knee. Dick I always knew, in my childhood days, as vicar of a church in a place called Stepney, whence flowed into our letter-box a regular stream of ingenious and amusing appeals for money. My parents told me that he was always poor, always over-worked, and very much of a saint; whenever I saw him he looked as if they spoke truth.

On a winter’s day in 1910—I having realized that I was called to ordination, and being an Oxford undergraduate—Dick paid another visit to my home. During it he suggested that I should spend a few days and nights in Settles Street. I sometimes wonder why he did so, whether there was any idea in his mind that I too might become one day a priest in East London.

On the next day I paid my first visit to Commercial Road, and “slept” for the first time in an [126/127] East London clergy-house (I say “slept,” for I remember now the oppressiveness of the small bare bedroom, the noise of the streets, and the uneasiness of my interior economy occasioned by a hastily-swallowed meal a few minutes before midnight). During the evening I was introduced to The Red House—a large restaurant and hostel for working-men, in Commercial Road, designedly constructed to resemble a flourishing public-house, but in which only “soft” drinks were sold and over whose swing-doors were white letters that read “Good Pull Up For Bishops.” “And,” said Dick, with a twinkle in his eye, “you might like to keep an eye for me to-morrow morning on The White House.” “Certainly,” I answered, with all of an undergraduate’s confident enthusiasm, “what’s that? and when does it open?” “Five o’clock,” he replied—and the twinkle grew brighter. “It’s a sort of club for men who are out of work, most of whom have slept the night in dosshouses or on the Embankment. You’ll only have to make tea for them, and keep an eye on them generally. They come in to get a bit of warmth and rest, a wash, and perhaps a shave. They stand more chance of finding work if they are clean and fairly presentable.”

In pitch darkness I stumbled across the street in the cold of the early morning: found a queue of poor fellows, wet and weary, waiting outside the doors: did what I could for them. But I was nonplussed when police arrived, and wished to interview all my clients. I sent a message across the street to Dick. In a few minutes he was with us, [127/128] old cassock obviously slipped over pyjamas, unshaven, eyes heavy with sleep but still twinkling with fun. “But, sergeant,” he said, “I can vouch for every one of them—except, perhaps, this young man from Oxford!” Leman Street took him at his word; and departed, laughing at his joke.

It was the morning after the Battle of Sidney Street (less than a mile away), an account of which I take from Thomas Burke’s “The Real East End.” [Published by Constable & Co. 3s. 6d. A shrewd and kindly book, that should be read by all who wish to have a true picture of modern East London.]

Sidney Street, Stepney, is a plain everyday street of small houses and a few shops; but it has its place in London’s history. It is the scene of the last battle ever fought on London’s soil, and the Battle of Sidney Street, under the direction of Mr. Winston Churchill, adds a richly coloured postscript to the Newgate Calendar. The thing seems almost legendary now. It began with the attempted arrest of some burglars in a Houndsditch warehouse. The burglars, caught in the act, shot and killed the three policemen who were rounding them up. During the mêlée history repeated itself. Within two stone’s-throws of Houndsditch, in the yard of the Red Lion at the corner of Leman Street, Dick Turpin and his partner, Tom King, were surrounded by Bow Street men. King was taken and cried to his friend, “Shoot, Dick, or I’m lost.” Dick shot, missed the constable, and killed Tom King. The Houndsditch affair bore an identical incident. One of the burglars, Gardstein, was tackled by a policeman. He called to a friend for rescue, and the friend fired at the policeman—and killed Gardstein. The policeman went next, and when all three of the police were down, the remaining [128/129] men escaped. But by the help of an informer, or nark—a far more effective second than Sherlock Holmes—they were traced to a house in Sidney Street and the house was surrounded. But they barricaded themselves in and managed, before the end, to show Chicago, in the early years of this century, how it should do the stuff it was to do in the nineteen-twenties and thirties. They even anticipated the quaint nomenclature of the game. Long before Chicago knew Scar-face Al, Sidney Street knew Peter the Painter. And Peter the Painter was just as elusive, and had as many lives as Scar-face Al. It was a common story in the district that this Peter the Painter, one of the burglars, did not perish in the general holocaust; that he escaped; that he had been seen wandering about the streets of the East End; and that years later he held high office in Soviet Russia. Possibly he did; and possibly he will live for ever, like Parnell, Oscar Wilde, Lord Kitchener, Hector Macdonald, and all those who have been seen alive long after they were dead. Legends are far more potent than truth. Those of my age will remember something of that painful drama of Christmas, 1910; which belonged more to a Central American capital than to London. The men barricaded themselves in the Sidney Street house. The police, armed, besieged them. They refused to surrender. From good cover they fired at the police, and the police fired back at the blank face of the house. For two days they resisted the siege. Then the Home Secretary, against this threat of guerilla warfare, ordered out a detachment of the Guards and himself accompanied them. But even with this they were not taken. They looked out from their barricaded cottage. They saw that they were surrounded. They saw that there was no hope of escape. Whereupon they delivered to the police, to the Guards, and to the whole social system [129/130] of London, one unequivocal gesture. They burned the house over their own heads, and died in the furnace. But the legend I have mentioned says that one of them walked through the fire. This fire disturbed the besiegers by bringing fire-engines on to the scene, and it is said that during this disturbance he made his escape. It may be so. If a man’s world-name is Peter the Painter, one can accept much more of him than one can accept of Mr. Brown or Mr. Jones. Anyway, whatever you think about it makes no difference to what Sidney Street believes about it.

Such was my introduction to East London. It can scarcely be described as dull; indeed that is not an epithet which can be applied with truth to anything that has to do with the city that lies eastwards of The City. I still remember that December night, as, thirty years after, when the then Home Secretary has been for the second time in his career First Lord of the Admiralty, and is at last Prime Minister, I walk occasionally along the street near The London Hospital that connects Whitechapel and Commercial Roads, and has not changed its name.

As I left Stepney a day or two later, to return to the bosom of my family, I happened to look from the tram-top across Commercial Road as I passed a block of tenement-buildings a few hundred yards eastward of Aldgate. Across a landing, open to the street, on the third or fourth floor I saw Dick walk, in a cassock that was—even at that distance—obviously not new, and a biretta that was split in front. Dancing round him were half a dozen children, all laughing. He laughed too. That is the picture of him which I like best to remember. [130/131] Though I cannot forget a Saturday afternoon, some years later, in Westminster. One of his St. Augustine’s girls was to marry a St. Matthew’s boy. Down Great Peter Street swarmed a number of her friends. At their head, laughing as ever, walked he in an old, a very old, frock-coat; on his head a famous top-hat, which was both green with age and Victorianly curly of brim, and was only taken down from the top of a wardrobe on state occasions.

A few more arches of the years passed by (if arches can be said to pass). In 1925 I found myself vicar of another St. Augustine’s in East London; that which the local jeunesse dorée not infrequently refers to as Orgustyne’s and is situate in Hergotestane (alias Hoggeston or Haggerston). Immediately, as is the destiny of all who accept unendowed and impecunious East London livings, I found myself confronted with the necessity of begging from the generous-hearted in other parts of London and England. It was necessary for me to raise, somehow, £10,000 wherewith to repair my dilapidated church, make the clergy-house sanitary and habitable, and build a parish-hall for my people.

Before writing my appeal I took a mile walk southwards. I crossed the old first-century turf British chariot-track to Camulodunum (Colchester), which the Romans replaced by a paved road as far as the Old Ford across the River Lea, and which their remote descendants named Bethnal Green Road. I also crossed, near to the London Hospital, the straight broad thoroughfare that takes its name [131/132] from The White Chapel that once stood at its western end; and found myself, after having rung the door-bell and undergone inspection by a maidservant through a small window almost on a level with the floor of the clergy-house entrance-hall, seated by the side of Dick on a large sofa in his top-floor dining-room.

“I must raise a pile of money for my St. Augustine’s,” said I; “you have been doing this for many years for your St. Augustine’s. Give me some advice.”

“Certainly not,” he answered, with a grin. “Successful appeals—like sermons, and many other things—must be original, must be your own.”

He was right. There was not much that he did not know about both human nature and begging.

A month later I posted the thirty thousand copies of my appeal, on the success of which much for Haggerston depended. The first of about eight thousand replies was a postal order for five shillings. It was accompanied by a half-sheet of notepaper that bore a Settles Street address, on which were written the words “To a chip of the old block.” It seemed to me a good omen. And so it was.

On a morning in the following year he was saying Mass, when he had a seizure. “I think,” he said to himself, “that this will be my last Mass. I think that I am going to die. But I must finish it. I must not alarm the server or the congregation. I must not die here.” He finished the Mass, leaning [132/133] on the altar with both his fore-arms. After a rest in the vestry, he felt a little better, staggered into the clergy-house, and decided to have a bath. In the bathroom he became so ill that he was unable to reach the door, but managed to fall in a dead faint across some empty hot-water cans, the clatter of which was heard by others in the house.

They sent him away to the country-house of relatives. Months later, after the local doctor had come and gone, non-committal as usual, Dick said to his hostess, “If I ask you a question, will you tell me the truth?”

“Of course I will, uncle,” she replied.

“Am I going to get well?”

“No.

“Then, will you do something for me?”

“Yes, my dear. Anything you ask.”

“Take me back to Settles Street. I want to die among my own people.”

She did.

He was not well enough to leave his room in the clergy-house; but, for a week or two, he was able to sit by the window from which he could hear the music and hymn-singing of the church-services, and from which he could now and then wave to his people and smile at them as they came out.

One May Sunday morning, after High Mass in Haggerston, an unknown woman said to me: “Father Richard asks me to tell you that he is at home again, and would like to see you when you have time.” I went to Settles Street the next day.

[134] “I’m afraid that you can’t see him,” said the housekeeper through the familiar small window. “He has had a relapse, and nearly died last night. The doctor has given orders that he is to see no one.”

“I’m sorry,” I answered; “but he asked for me. I must see him.”

She fetched the London Hospital nurse who was looking after him. “Quite impossible,” she said; “doctor’s orders.”

I repeated that I was not leaving the house until I had seen him.

“May I ask your name?”asked the nurse. “Certainly,” I answered: “Wilson.”

“Oh!” she said. “Well! Just for two minutes.”

He lay propped up in bed, obviously not long for this world. But a flicker of a smile lurked, as ever, in the corners of his mouth, and from his eyes shone still the old gallant twinkle.

“How did you manage to get up here?” he whispered.

“I don’t quite know,” I answered; “I merely kept on saying that I would not go away until I had seen you.”

“Yes!” he said, and almost laughed aloud; “ours is a wonderful family, isn’t it?”

We did not talk much, and I kept to the two minutes. As I rose from the chair to go, he said, “Give me your blessing.” After I had given it to him, I asked for his. He blessed me; and added, the last words I heard from him, “Be a good priest.”

[135] The Church Times of May 13th, 1927, contained the following:

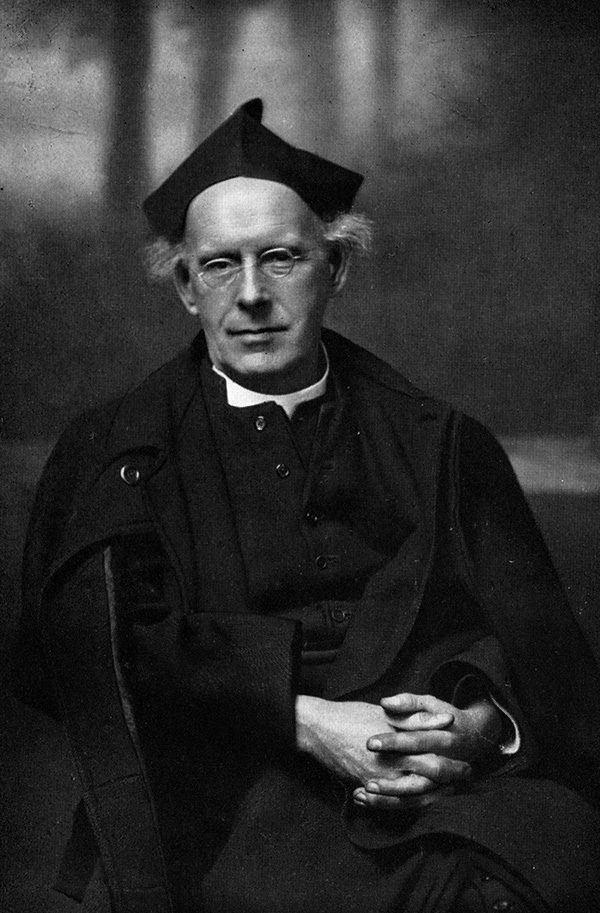

FR. RICHARD WILSON

DEATH OF FRIEND OF HOP-PICKERS AND TRAMPS

On the door of the clergy-house of St. Augustine’s, Stepney, on Tuesday morning there was pinned a half-sheet of notepaper. On it was written: “Father Richard passed away this morning at 12.50.” Everybody round about Settles-street and Commercial Road knew that Fr. Richard was ill, and that he had come back from the country, not because his health was restored, but because he wished to die in the place he loved. None the less, the simple sentence on the clergy-house door came with the shock which death, however long delayed, invariably administers.

Fr. Richard had been connected with St. Augustine’s for forty-three years. At first, after short curacies at Haddenham and Haggerston, he served as assistant curate under his brother Harry, who, responding to Bishop Walsham How’s appeal for workers in East London, had exchanged his pleasant family living in Oxfordshire for St. Augustine’s. Together the two brothers worked with Fr. Smallpeice, now of St. Bartholomew’s, Brighton, as colleague. They early laid the foundations of all those institutions for which St. Augustine’s is now famous.

Fr. Richard’s large heart impelled him from the beginning to lavish his love and merriment on the bottom dogs of all. The White House was a particular delight. Here the dirtiest tramps were given a welcome and made to feel they were not “cases,” but guests. If you go into the crypt of the church you will find [135/136] many gas-rings and cooking-appliances, for it was here, at Fr. Richard’s invitation, that factory girls came at midday to cook their bloaters and rashers. Many hundreds of times he must have been imposed upon by those who sought his help; but he never lost heart. Indeed, signs of waning interest only appeared when one of his down-and-outs began to make good, and wear a clean collar. He had a wonderful knowledge of the underworld of East London, and his very last activities were the attempt to restore to normal life girls of the East End who had begun to walk the streets. It is true to say of him that his life was a complete negation of self; no consciousness of self-denial that was a natural, spontaneous, Christian altruism, the like of which it would be very hard to find.

Among the Jews who abound in the neighbourhood he was known affectionately as “Father Dick”; and only a few years ago he was the recipient at their hands of a large cheque that accompanied a testimonial—the cheque he passed on to the London Hospital. It puzzled them that he should do so much for them, and yet not attempt to proselytize. They did not realize that his every action was a sermon. Once in an air-raid a house in the parish was demolished, and three families rendered homeless. Fr. Richard went straight out and collected them, and brought them into the clergy-house and kept them there until they could find new homes. He saw to it that they had Kosher food, and he did not forget at Paschal-tide to provide them with Passover candles. If actions speak louder than words, then Fr. Richard was a magnificent preacher of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. In the pulpit he established no claim to Christian oratory; and yet the people loved to hear him. “I suppose,” said one of his admirers, “that Fr. Richard couldn’t really preach for nuts, but we’d [136/137] rather listen to him than to any other of the clergy.” [His memorial in St. Augustine’s is the pulpit. His giving-out of notices was an unfailing delight. After he had purchased ground in the Plaistow Cemetery for the exclusive use of St. Augustine’s communicants, he announced the fact, and impressed on his hearers that they should give instructions in their wills that they wished to be laid to rest there. “For myself,” he concluded, “I have given up being buried at Bow.”]

In 1902 Fr. Richard succeeded his brother as vicar, and by that time he had begun his work among the hoppers, which has since been widely imitated. He first went into the Kentish hopfields as an ordinary hopper in order to be with his people, during their annual migration from East London. He did his day’s work with the rest, and earned his day’s pay. From the knowledge thus gained of a hop-picker’s needs, and the opportunities of serving them, there came the beginnings of the organization which has entirely transformed the conditions under which the hop-pickers work. At first, he rented a cottage at half a crown a week, and got a nurse from the London Hospital to attend to the hoppers’ ailments. Now the parish owns a former public-house, the “Rose and Crown” which stands at Five Oak Green. Here is a hospital, with children’s ward of six cots, an outpatients’ department and dispensary, and, in other rooms, places where hop-pickers may sing and dance of an evening, and in which they may write their letters. There is a canteen also; so that it is a real public house, except that no strong drink is sold there.

The outside is little changed: the old swinging sign stands by the road-side, bearing the name of the house on it; but beneath it, “Little Hoppers’ Hospital,” and in the corner the name of the landlord, in the customary sloping letters, “R. Wilson.” Across the facade is the legend in bold black letters, “Tomlinson’s Fine Ale, Stout and Porter.” The new landlord [137/138] did not paint them out, but just added below, “Not Sold Here.” Recently the courtyard on its highway-side has been enclosed by a shelter running the length of the frontage. It is the “Rose and Crown’s” war memorial, and the inscription says:

In Happy Memory of Old Friends,

Who loved Hopping and who loved this place very dearly,

Who gave their lives for Old England and for us,

1914-1918.

Lord all-pitying, Jesu blest; Grant them Thine Eternal Rest.

Just as Fr. Richard followed his people into the hop-fields, so he identified himself with their interests at home. He was instrumental in starting a carmen’s trade union, and the local branch of the N.U.R. still holds its meetings at St. Augustine’s.

Fr. Asher, who succeeded him as vicar in 1922, gave him the Most Comfortable Sacrament soon after midnight on Monday morning last, and the greathearted priest passed peacefully to his eternal rest on May 10th, in the seventy-first year of his age and the forty-seventh of his priesthood. May he rest in peace!

The following was written by a Jew: [Basil L. Q. Henriques in The Indiscretions of a Warden.]

He was one of the most saintly men, with a serenely beautiful smile, whom I have ever known. He just beamed on every one he saw, making them feel that he loved them, as I really believe he actually did. He was as popular with the Jews as with the Gentiles, and many a Jew trusted him so implicitly as to bring his troubles to him. His greatest work was among the hoppers and the destitute and homeless.

In his dosshouse in Settles Street there was to be [138/139] found the weirdest collection of down-and-outs imaginable. Some were ‘Varsity men who had sunk to the lowest depths and had lost every vestige of self-respect, others were tramps who desired no other kind of life. Many were criminals. They were a miserable-looking crowd. As soon as they showed signs of regaining their self-respect, he promoted them from the dosshouse proper to what he called the House of Lords. Here at night “their lordships” debated the topics of the day. One of the rules was that you were never allowed to talk about the others in any other way than “the noble lord.” To be called by such a name made these wretched nobodies believe that, after all, they were somebody, and their confidence began to return to them. Many a hopeless creature went back once more a happy member of his family after a year of the Father’s benign influence.

We used to get our house-boys from him. Quite often they stole from us within a week, and when we told him he smiled and said: “I’ll send you another.” One day he sent us a lad who was put on to scrubbing the stairs. He was so lousy that the lice actually fell off him as he worked. I rang up the Father and said I simply could not keep the boy. “Send him round to me,” he said: “I’ll soon clean him up.” I feel very much ashamed of myself, even now, when I think of the dear man kneeling down and picking the lice off the boy one by one. This seems to me the highest act of love I have known.

Clergy such as this are a glorious revelation of God. They bring the light of His Love into the darkest corners of London.

Luke Paget, Bishop of Stepney from 1909 to 1919, (of whom his biographer says that “his spirits rose in Old Ford Road and Aldgate, Crisp Street, [139/140] Poplar, Petticoat Lane, Brick Lane and Bethnal Green Road, and only tolerated the dullness of Hackney Road because the Queen’s Hospital for Children stood there, and as the children lie out on the balconies they recognize the Various tram-conductors by apt, rude nicknames, or hold competitions as to who can spit furthest”) wrote:

Up to the time of the war I always spent a long week-end in the hop-gardens, and I always enjoyed it. As a rule Fr. Richard lent me his caravan. Once I spent a splendid night in a tent on a wonderful bag of straw; and once, when I was settling in for another night in a tent, I was called by way of contrast to be the guest of a most hospitable millionaire.

I wish you could have been at one of those singsongs. The ingenuity was simply marvellous. Some of our own people were really pathetic, some irresistibly comic: once (and it was a great occasion) Mr. Charles Coburn came and sang to us quite delightfully; and once, by way of a real variety, competitors were invited to see if any one could sing a serious song with a live piglet (lent by a farmer friend) in his arms. It was impossible!

Sunday was delightful. Quite a lot of us came early to a Sung Eucharist, and we had Merbecke and a good many hymns; and then, late in the evening, there was the procession, the people carrying flaming torches and with our Cross leading the way, and then a mission service on a neighbouring common. I shall never forget the beauty of the sight, or the delightful reverence and earnestness of the good people. The farmers were most kind and good to us all, and, generally, when the day’s work was over, they let us sit by great bonfires, and, more than once, I remember they sent us out a large basket of perfectly [140/141] magnificent potatoes; and one came and spoke very kindly of the good which he thought had been done.

Some nice Oxford men came and helped us to enjoy ourselves—and we did! I well remember how, when a very pleasant party from Christ Church asked me to dinner on Sunday, the undergraduate who was acting as cook said to me in a tone of despair: “I don’t know what to do with these sausages. I’ve had them over the stove for ever such a time, and they are still dreadfully pink.”

On one of my first visits to the hop-fields I believe that Fred Harke, a coster from Stepney, suggested rolling me in the hops, a suggestion fortunately negatived by Fr. Richard. Yet the custom dates time out of memory of man, when the stranger was rolled in the crop before he was sacrificed and his crop-identified blood returned to the earth to ensure next year’s harvest.

St. Augustine’s Church, Stepney, had its stately services and (I think) the best congregations in that part of the world, with a sense of reverence and devotion and fellowship such as I hardly saw elsewhere.

I can’t tell you of all the things Richard Wilson did for his people, always with quickness of insight, humour, and delicate consideration for their feelings. [Elma K. Paget. Henry Luke Paget.]

“I met the late Bishop Luke Paget,” a friend has written to me, “on two different occasions at Fulham Palace. On both he told me that he was once standing outside St. Augustine’s after Sunday Mass talking to the people as they came out into Settles Street, when a Jew went up to him and said of Fr. Richard, ‘When I see that gentleman walk along [141/142] the street, I feel that I have seen the mind of Jesus Christ.’“

East London will not soon forget him.

To this day, thirteen years after, my letters are occasionally delivered in Settles Street; presumably because there are sorters in the Whitechapel Road Post Office for whom “Wilson, St. Augustine’s” still means only Dick.

Only the other night the habitués of one of the Hackney Road public-houses were discussing air-raids and Hitler’s current war. Richard’s name came up. “Yus,” said one; “‘e was a man. Aht in every raid, ‘e was. An’, though ‘e was a teetotaller, ‘e allus ‘ad in ‘is pocket a li’le bo’le o’ somethin’; in case ‘e come across some one ‘oo might need a drop.”

When arrangements were being made for his funeral, it was discovered that Dick had ordered the undertakers to cut on a brick, that was to be placed at the head of his grave in St. Augustine’s burial-plot at Plaistow, three words only: “Richard. A priest.”

At the grave-side I happened to look up as Fr. Asher, his friend and erstwhile curate with whom Dick had changed places as vicar, was sprinkling with holy water the plain coffin of the sleeping body to be laid in the gentle arms of mother earth. He was smiling.

In the hearts of the immense crowds of Gentiles and Jews which had packed the church and thronged the streets that morning, and which stood round his [142/143] grave, there was sorrow at the departure of a loved and trusted Christian priest and friend; but there was some measure of happiness too, that the long weariness and the trials and indignities of bodily weakness were ended, that the victorious soldier was home from the wars. It was a happiness that carried with it a sense of great gratitude to the God who had been so good as to lend us Richard for a while.

Fr. Asher smiled for us all, who believed in both the resurrection of the body and everlasting life.

East Londoners can be fickle folk; invertebrate, irresponsible, casual in the extreme. East London priests not infrequently find it difficult to keep their spirits high, to ignore the not inconsiderable loneliness which is their inevitable lot, to be content with small returns and slow progress, to serve tables with a glad heart, to keep stiff upper lips and to refuse to admit defeat.

On my less roseate days it is my wont to recall to mind my two heroes, the bishop and the priest, who asked nothing of life but to spend themselves and be spent, through the poor of East Africa and the poor of East London, in the service of him who was once the poor man of Nazareth; and who were granted their requests.

I look at Dick’s photograph. Of medium height. Apparently untidy, but actually most particular about cleanliness, if indifferent to the character or the shape of clothes. Well-kept hands and fingernails. Very gentle mouth, the corners of which were [143/144] always beginning to smile. Seemingly indifferent to the physical requirements that bother ordinary mortals; such as food, sleep, health, and comfort. Physically, as hard as nails; spiritually, as gentle as a mother. Outwardly, not at all striking or arresting; until you looked at his eyes. They were clear blue. They looked at you with the trust, the frankness, the love and loyalty, of a child; and with the wisdom of a child, which is often great. There were small lines round them; because he was always laughing, because he was a Troubadour of God, because in all the years in East London he never lost his sight of God or his faith in East Londoners, though he had looked at all there is to be seen of the seamy side of life; because, at the end of more than forty years, he was still looking for lost sheep and finding them, one by one, like that Good Shepherd who, surely, laughed and laughs.

I remember his last four words to me. I think that he laughs still, with the child-hearted merry men of God, in the courts of high heaven. I think, too, that he has even greater joy to come, when there reach him in the eternal city crowds of East Londoners who, under God, found the way there in “Richard. A priest,” and not least through the laughter of his gay and unquenched spirit.

My sword is Strength, my spear is Song;

With these upon a stubborn field

I challenge Falsehood, Fear and Wrong;

But Laughter is my shield.

[Arthur Guiterman. Re-armed.]

To die for love is a great adventure. To live for love is a far greater adventure, and that means bringing love to meet love every day in the common things of life. [H. F. B. Mackay. The Message of Francis of Assisi.]

Like a knight in glittering armour,

Laughter

Stood up at his side.

[W. R. Benét. The Last Ally.]