[15] RECEIVED WITH THANKS

PETER FRANCIS TINDALL

NOBODY knows what an idiot a newly-ordained deacon feels, except a newly-ordained deacon.

It was on St. Thomas’ Day, in the otherwise comparatively unimportant year 1913, that I, four days over the prescribed minimum age of three and twenty, was ordained in Canterbury Cathedral by Archbishop Davidson.

An optimistic archdeacon, who knew nothing whatever about me, affirmed that I was “apt and meet, for learning and godly conversation.” No one was forthcoming to accuse me in public of “any impediment, or notable crime.” I was adjured to be “grave, not double-tongued, not given to much wine, not greedy of filthy lucre, the husband of one wife.” His Grace laid his hands upon my head. I rose to my feet, a clergyman in The Church of England as by Law Established.

Two days later, from the same railway-platform from which it had periodically been my more or less unwilling wont to set out to a Sussex public school, and with much the same sense of uncomfortable apprehension as when I had been a new boy, I travelled, intentionally under cover of night, [15/16] by the gentle and unhurrying permanent way of the late and unlamented South Eastern and Chatham Railway towards the luckless and unsuspecting town of Ashford in Kent.

After some hours there emerged from that junction, at which travellers to Rye or Canterbury must leave their London to Dover train, a sombre figure of about six feet in height who hoped that his condition of extreme nervousness was not as apparent as he feared it to be. He was swathed in a brand-new edition of the Prince of Denmark’s “customary suit of solemn black”; girt about the neck by a stiff starched collar of some height that still appeared to be the wrong way round; and crowned by a black hat of ample dimensions and non-committal design. He walked out into the December night, carrying in neatly-gloved hand an equally new suitcase. As he passed the respectable villas in Church Road, he was convinced that every passer-by was looking at him; and turned up his coat-collar.

But a few minutes later he was at ease. The front-door of the clergy-house closed with a grand slam (clergy-house front-doors still do, always). A loud voice called, “Where ‘s my deacon?” Firm steps strode up the creaking staircase. The door of the sitting-room burst open; and he was standing, with his large hands on my shoulders, looking down at me, and saying, “Well! Sonny!”

If for nothing else I would always love him for that moment. But there was much else.

It is to be hoped that the Church of England will [16/17] ultimately realize the wisdom of requiring deacons to remain at their theological colleges until the time of their ordination to the priesthood.

Under the present system many young men reach their parishes after only twelve months of training for what will be agreed to be a profession that embraces almost unlimited possibilities for both usefulness and the opposite. To preach a sermon may be to affect a soul for eternity. To hear confessions is to invite, not only penitents to absolution, but also the perplexed to the highest human tribunal of counsel and direction. To perform as a hesitating amateur the most important office of a priest—which is to offer at an altar the “perpetual memory of the one, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world”; and from that altar to take to men and women the sacrament of him who alone can give satisfaction in this life and in that which is to come—seems little short of an affront both to the congregation at Mass and to the Christ who, presumably, called the young man to the priesthood, and who, without doubt, is that sacrifice and sacrament. To deal with the souls of either children or the dying, without having previously received such instruction as shall enable him to act without hesitation or great chance of error, seems scarcely fair on either the clergyman or his clients.

It may be possible for the man to learn these, and the other, arts of his profession in the twelve months at his theological college. On the other hand, it is not unknown for him to reach his first parish [17/18] blissfully ignorant of all but their most elementary principles; and consequently to be dependent on his vicar, who presumably is already sufficiently occupied, to correct his mistakes and to teach him both his duties and the manner in which they should be performed. The responsibility of an incumbent who engages a deacon is, of course, great. As a rule he realizes this, and is anxious to help him in every possible way. But young men are not always willing to learn from old fogies; and youth still sees visions of how the parish really ought to be run, and how the church-services could be made far more attractive. One wonders, too, whether there is any other skilled profession for which a year’s training is considered adequate.

Nor does it seem likely that there will be an increase in the already comparatively small number of parishes which can afford to pay a minimum of £200 a year to a man who, through no fault of his own, can do little in the first year to earn it. It is already far from easy for prospective deacons to obtain posts in parishes. This is bad for them. It is not well that, at the beginning of the life to which you have looked forward for a number of years, and to attain which perhaps both your parents and yourself have made considerable sacrifices, you should get the impression that you are not wanted.

In the meantime, it will be appreciated that for the deacon much depends on both his first vicar and his first parish.

I do not know whether, on a seventeenth day of [18/19] December, “There was a star danced, and under that was I born”; but the fact remains that I have always been one of the world’s lucky ones, and never more so than on the day when Peter Francis Tindall invited me to be one of his curates at Ashford.

The fourteenth edition of The Encyclopaedia Britannica (1929) contains these paragraphs:

ASHFORD, urban district, Kent, England, 56 m. S.E. of London by the Southern Railway. Population (1921) 14,351. It lies on a slight hill in the plains under the Downs near the confluence of the upper branches of the River Stour, and is a considerable road and rail centre. Ashford (Esselesford, Asshatisforde, Essheford) was held at the time of Domesday by Hugh de Montfort. A Saturday market and an annual fair were granted to the lord of the manor in the 13th century, and further annual fairs were granted by Edward III and Edward IV. The fertility of the pasture land in Romney Marsh to the south caused the cattle trade to increase from the latter half of the 18th century, and a stock market was established in 1784.

The fine Perpendicular church (St. Mary’s) has a lofty tower and many interesting monuments. From nearby quarries marble was formerly worked extensively, supplying stone for the cathedrals of Canterbury and Rochester and for many local churches. Ashford has agricultural implement works and breweries; and the large locomotive and carriage works of the Southern railway (South-Eastern and Chatham section) are here.

Tindall was a Yorkshireman. As large of heart as he was of frame; as incapable of mean thoughts or of malicious words or acts as (in former years) [19/20] of a foul on the football-field; as generous and openhanded as are all genuine sportsmen; as determined and courageous of convictions as are most sons of the county of broad acres; veritable man of God, whom it was impossible to ignore: he was ordained deacon under that great priest, Rhodes Bristow, to that great South London church, St. Stephen’s, Lewisham. There he learned in its fullness both the Catholic Faith, and its natural and right expression in dignified ritual and ordered ceremony; there he saw the sacraments at work among men; and there he found what a parish-priest should, and could, be.

In the eighteen-eighties he was appointed to the important living of Ashford. He found his church and parish sunk in the depths of protestantism. Its only altar was an uncovered wooden table; beneath it, a dust-covered wine-bottle into which was poured back after evening communion what was left in the chalice. Slowly he began to put things right.

After a few months, friends in Lewisham gave him, at his request, a pair of brass candlesticks and a large brass altar-cross. He invited the churchwardens to dinner, fed and wined them well, showed them the new ornaments for their church. They liked the look of them.

“Well, then, gentlemen,” said their young vicar with an infectious smile; “let us take them into church.”

Somewhat to their surprise, the officials found themselves carrying by night across the churchyard [20/21] a pair of candlesticks, and subsequently placing them on either side of a cross on the new altar.

“Don’t you think they look rather nice?” asked their host.

Yes, they did.

“Then let us leave them there,” said he; and explained to an indignant congregation on the following Sunday that, although he was responsible for their arrival, it was the churchwardens who had placed them in position.

Inevitably he made enemies; men of large minds always do. His salary was to some extent dependent on pew-rents; a number of the holders declined to pay, tried to starve him out, nearly succeeded. A relation died, and bequeathed him a considerable legacy. Thereupon he summoned a meeting of church-people in the Corn Exchange, situate in the town’s main thoroughfare, Bank Street. Having informed the large concourse about his windfall, he concluded, “If I walk on one side of Bank Street, and the whole of Ashford walks on the other side; I wish you to understand, ladies and gentlemen, that nothing in the world will induce me to cross over.”

But in 1913, when that deacon was so fortunate as to join his staff of four, such alarums and excursions were “Old, unhappy, far-off things, And battles long ago.” The chief Sunday service was a Sung Eucharist, with a large congregation and a devout and well-trained choir. The Eucharist was said daily. On Sunday evenings, St. Mary’s, the parish church, which had accommodation for some [21/22] fifteen hundred, was well filled, the galleries being crowded with men. The vicar was reputed to hear more confessions than any other priest in East Kent. A large mission-church had been built in South Ashford, and was a flourishing concern: and there was a queer and rather lovable small chapel in the poorer quarters around Forge Lane. Church House, the men’s club, flourished exceedingly and numbered its members in three figures. And Tindall was a name to conjure with all over the clean, busy, attractive, and rapidly-growing country town; as well as in many a neighbouring village and hamlet.

But, although the church-services were a model of dignity, orderliness, and reverence, no Eucharistic vestments were worn at the altar. For many years the vicar told his people that these were the right and fitting apparel for a celebrating priest; he always added that, since they could not of course be said to be essential to the validity of the sacrament, he would not wear them until they had been given to him by the congregation; for he could not, and would not, bring himself to turn away a single one of his parishioners from the only churches that were available. He never got his vestments; but it is not without significance that his successor should have been able to restore them without trace of opposition.

The clergy-house was small, holding but two of us. It faced the spacious old vicarage at the entrance to the churchyard-close, from which the fine tower of the parish church rose in the centre, and as the [22/23] crown, of the country town. Down the road towards the station lived the third, David Railton, now rector of Liverpool, with his wife and young family. Across the railway in artisan South Ashford resided the fourth. To each and all of us the vicarage was an open house; its master, “the vicar,” was always at our service and was our veritable father in God.

Every Sunday evening, when the long and strenuous day was over, he and his kind wife entertained the four of us. After dinner we would adjourn to his large study, smoke his cigars in long leather armchairs, in winter round a roaring fire, and delight in his reminiscences of other days; such as when the Ashford Volunteers, marching proudly through their home-town after church-parade, were bidden by their resplendent commanding-officer to “Left wheel”; who, realizing that this manoeuvre would lead his forces into a butcher’s shop, with admirable presence of mind rasped out the original but adequate and intelligible counter-order, “Damn it! I mean; go down Bank Street.”

In that same room we would foregather again on the following morning for what had the dignified title of Chapter Meeting, but was never anything more serious than a friendly and mutual arrangement, conducted in clouds of tobacco-smoke, of the week’s programme. For although we certainly had a vicar who was accustomed to be obeyed, there were among us no symptoms of the dread disease sometimes diagnosed as “vicaritis.” If he did not address us as “Sonny,” it was always as “Leslie,” “David,” or “Brother.”

[24] In such happy surroundings the apprentice began to learn his trade, and the fledgling to spread his wings.

I had soon been delivered of my first sermon; a precocious infant that embodied practically the whole of Church Doctrine, and at which I sometimes still look on such rare occasions as I am tempted to think that I have preached well. To this day I marvel at the patience and powers of endurance displayed by the Forge Lane congregation.

Before long I had made my first acquaintance with death, a young mother in child-birth; and have never forgotten it.

Old John Elgar, the verger with the lined brown face and the curt gruff voice that camouflaged a heart of gold, saw me safely through my first baptism; I am uncertain which of the two of us was the more nervous. I know that when, in response to my request, “Name this child,” the godparent replied, “Herbert Arthur,” the babe nearly came to an untimely end; for her answer was precisely similar to that made by another godparent by the font in St. Michael’s Church, Croydon, when the infant was myself. Which, as old John subsequently remarked, was “a cohincidence” (the accent being on the third syllable).

I learned, both from Tindall and from Railton, how to preach to a thousand; and how to say weekday Mattins with recollection, though the only congregation was old John. “The thirteenth morning,” I would announce; and follow it with the psalm’s [24/25] first verse. There came no reply; until the congregation looked up from his well-thumbed prayer-book, and asked “What mornin’?” “The thirteenth, John.” “Thought it was the fourteenth.” To this day I cannot say Psalm 20 without thinking myself back in the Lady Chapel of Ashford parish church, and hearing the sonorous statement, “Now know I that the Lord ‘elpeth ‘is hanointed, an’ will ‘ear ‘im from ‘is ‘oly ‘eaven; heven with the ‘olesome strength of ‘is right ‘and.”

I learned both how to be as gentle as would your own mother with the sick and the old, little children and the dying; and at the same time how to try to be as good at games—especially at cricket, in Kent of all counties—as the men you played with. Every Saturday David and I would consume a vast lunch together, at his expense; and play cricket all the afternoon for the Church House Second Eleven. There came a memorable day on which was to take place the match of the season, Church House v. Ashford Town. So long as we won this game, the vicar did not mind if we lost all the rest. The wicketkeeper of the first eleven was hors de combat; consternation spread throughout our camp on the Friday night; “Better play the lad,” I overheard the vicar say to the captain, who took his advice. We won the toss, batted first, and lost half our wickets for a ridiculous total. “It’s up to you, sonny,” said Tindall, as I sat by his side and buckled on my pads. My partner (who died of wounds in Mesopotamia before the year was out) and I were [25/26] not separated until we had put on over a hundred runs. There was a fast bowler who refused to have an extra-cover. Still, at times, I can see the green-capped bespectacled chemist, fielding at cover, chasing the ball to the boundary; and the tall black-clad figure of the vicar cheering because it was his deacon who was doing something to save the situation. But, although the congregation in church on the next evening was immense, I thought it the better part of valour to refuse subsequent invitations to play for the first team, and to content myself with more carefree Saturday afternoons with David and the reserves.

How never to be ashamed of, or apologetic for, your “cloth”; and never to do or say anything, anywhere, that might bring into disrepute or disregard the honour of the whole priesthood. How to go on saying your private prayers, making your confessions, reciting your offices of Morning and Evening Prayer, when nobody knows or cares whether you do or not. How to be friendly with men and boys, without spoiling them or making favourites. How to cope with the ladies of many ages who wrote you little notes inviting you to tea and country-house tennis-parties, or said that they wished to consult you about their souls because your last Sunday’s sermon was so wonderful. [Though it was from Canon Goudge at Ely that I learned the dictum: Fear no man, and do right. Fear all women, and don’t write.] How to talk to children: there were no Catechisms at Ashford, but there were the most delightful [26/27] children’s services, and hundreds of names were on the Sunday School registers. How to be at all times—especially with those who did you the honour to work for you, voluntarily or otherwise—simultaneously and unceasingly both a priest and a gentleman (though the terms are synonymous, or should be). How to go straight on—through unpopularity, whisperings, active opposition, disloyalty, or ingratitude—doing what you know to be right, irrespective of anything that any one may say; “Meet with triumph and disaster, and treat those two impostors just the same.” And—in the later days, when both he and his erstwhile junior curate were no longer at Ashford, though his heart was still there—how to be laid aside from active work, suffer pain and discomfort, and close one’s eyes in the last long sleep, still both a Christian priest and a Christian gentleman. Such were some of the lessons that he taught me, consciously or otherwise, in my more callow days.

And round me, during the spring and early summer of 1914, lay The Garden of England. I wonder whether any of those who were Tindall’s choirboys in those days remember Saturday afternoon bicycle-rides to look for wild lilies-of-the-valley on Elham Downs, or bicycle-paperchases through Wye and Brabourne; whether any of the young men who then served at Ashford altars recall long evening rides after work, through Ham Street, over Romney Marsh, through Ivychurch and St. Mary’s, to bathe in the sea at Dymchurch, and return—bloated by [27/28] vast quantities of tea and eggs—under the moon by Aldington Knoll (where the fairies dance on Midsummer Night) and Willesborough. Ever since those diaconate days it has been my lot to live among London streets or slums; but still I hear the call of Mrs. Botherby’s fifth continent, [The world, according to the best geographers, is divided into Europe, Asia, Africa, America, and Romney Marsh. The Leech of Folkestone.] and now and then am able to answer it—still hoping, as when I first read The Ingoldsby Legends, to see “a witch weathering Dungeness Point in an eggshell, or careering on her broomstick over Dymchurch wall.”

The first of this century’s wars between England and Germany broke out on August 4th. Within a few weeks many of Ashford’s men had joined The Buffs, and gone to the East. Tindall was offered, and accepted, the living of St. Mary and St. Eanswythe, the parish church of Folkestone. He took David and Leslie with him. I was left, until his successor was appointed, to cope with the parish church as well as a deacon could; an experience that was doubtless good for me, but of dubious advantage to Ashford. But I did not relish Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark; and, soon after my ordination by Archbishop Davidson to the priesthood, offered myself to the War Office as an army chaplain.

On an afternoon in March, 1931, I was travelling to Birmingham to preach. I opened my evening paper and read:

CANON’S WAR-TIME VIGIL RECALLED

GAVE FAREWELL BLESSING TO THOUSANDS OF TROOPS

ROAD OF REMEMBRANCE

DEATH OF A FORMER VICAR OF FOLKESTONE

[29] One who, almost every day of the war, stood at the top of the Road of Remembrance at Folkestone, waving farewell to soldiers going overseas, has died at Little Beverley, Canterbury. He was Canon P. F. Tindall, Vicar of Ashford, Kent, for over 26 years, and Vicar of Folkestone from 1914 to 1926.

He watched hundreds of thousands of troops march to Folkestone Harbour to embark, waved his hand to each party as it passed him, and called: “Good boys; good boys; God bless you.”

He officiated at the funeral of the 60 victims of the German air raid on Folkestone in 1917, and performed good service during the arrival at Folkestone of Belgian and French refugees.

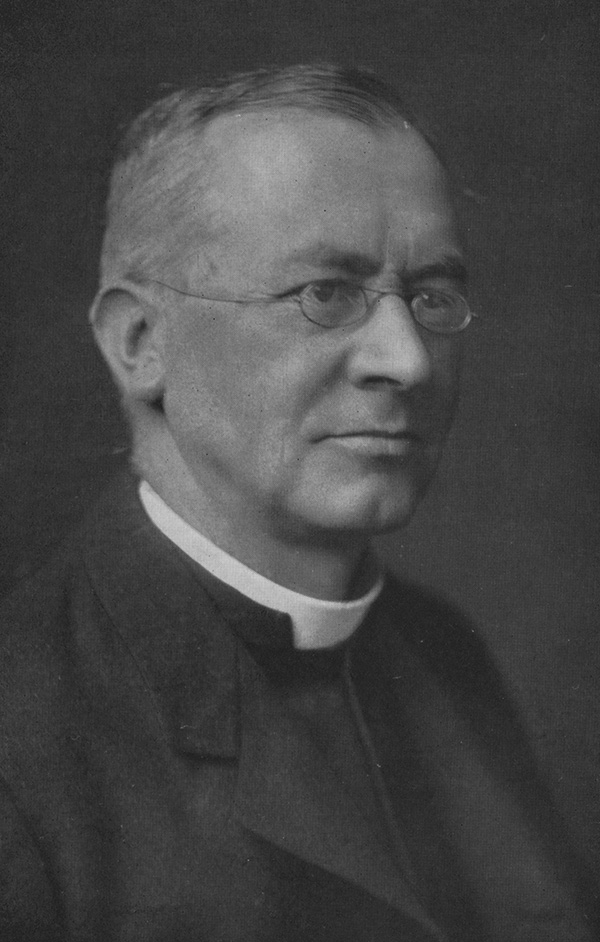

I had seen him frequently during the seventeen years: but the picture in my heart that I keep of him is of the vicar of Ashford; a little grey, but hale and upright; firm of mouth and chin, but with eyes behind gold-rimmed spectacles that were nearly always twinkling with merriment; shrewd of judgement, but kindness itself; knowing all that there is to be known, by human man, of human nature, but still keeping faith in it; welcoming a raw deacon with “Well! Sonny!”

[30] He was a Man. I owe him more than I can ever express or repay; and am by no means unique in this respect.

Nothing will mix and amalgamate more easily than an old priest and an old soldier. In reality, they are the same kind of man. One has devoted himself to his country upon earth, the other to his country in heaven; there is no other difference. [Victor Hugo. Les Misérables.]

I think that to have known one good old man—one man who, through the chances and rubs of a long life, has carried his heart in his hand, like a palm branch, waving all discords into peace, helps our faith in God, in ourselves, and in each other, more than many sermons. [G. W. Curtis. Prue and I.]