Long before the close of the Middle Ages the general lines of the arrangement of the altar and its surroundings had in the West settled down to one type. An altar arranged in conformity with the reference of the Prayer Book to the remaining of the chancels as in times past, and to the ornaments in use in the second year of Edward VI, is to-day very commonly called an English altar. But the English tradition was not isolated; all over the West (with the possible exception of Italy) in Flanders, in France, in Germany no less than in England high altars and lesser altars were of the same type.

Considerations of convenience, dignity, and beauty had determined the evolution of the altar and its setting, and had secured the maintenance of the tradition when once it had been formed. The men of the Middle Ages were sincere artists and fine craftsmen they were, above all things, practical; and were superior to the vulgar temptation to display their skill [3/4] at the cost of convenience. Their work was designed in reference to the church as a whole; the chancel in its entirety was regarded as the setting of the altar, and the effects which they produced were therefore completely harmonious.

Though, as has been said, the mediaeval arrangement of the altar was one and the same throughout Western Europe, yet it consorted even better with the English fashion in architecture than with the Continental. The English tradition of church planning was persistently faithful to the square east end, in spite of the attempt made during the period of Norman influence to naturalize in England the apse of the Continental Romanesque. In this square east end the window was a dominating feature. Its sill was almost invariably brought down to within seven feet of the altar pace, leaving below it room for the altar and for a reredos above it of equal height with the altar. The floor-levels were kept low, the dignity of the altar was secured by making it as long as possible in proportion to the width of the chancel, there was no attempt to give it prominence by elevating it upon a number of steps. Above the altar, as may be seen at Geddington and other places, there was a reredos of stone, alabaster, or wood, or a hanging of loomwork or needlework. From the east wall projected rods, carrying the riddels or curtains, the ends of the rods being often supported by riddel-posts, on which were set sconces for tapers. The altar itself, of which the front was usually of plain ashlar and unornamented, was [4/5] always covered by the frontal. There were upon the altar no shelves or gradines; the ornaments, two candlesticks, and a cross, if no representation of the Passion was portrayed upon the reredos, were set directly upon the linen cloths which covered the mensa.

This arrangement of the altar persisted, though with Renaissance detail, in many places on the Continent until almost the close of the eighteenth century. In England its lines might still be discerned beneath the poor work which the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries brought into many churches to supply the losses caused by Puritan iconoclasm. But the Oxford Movement, fostering the desire to recover for our sanctuaries their lost beauty, set men seeking on the Continent for what they believed to be Catholic customs, and the old tradition became obscured.

The following of modern Roman customs in an old church produces always the most deplorable results. The setting of the altar upon several new steps throws at once the whole chancel out of scale, while the addition of a gradine or gradines brings the bases of the altar ornaments almost to the level of the sill of the east window. Behind and above the gradines a reredos or a dorsal and tester of great height cuts into and obscures the window itself. Ornaments out of all proportion to the size of the altar complete the discordance, and even those who know little of the old arrangement for which the chancel was designed must feel instinctively that something has gone wrong, and that the new altar in the [5/6] old church is as a patch of vivid and inferior stuff upon a garment old but still most comely.

It is the aim of the Warham Guild to assist those who are conscious of the value of the old tradition to recover it, and to design for our churches the type of altar which they were built to enshrine, a type so beautiful in itself that none who has become accustomed to it can ever be satisfied with any other, and—above all—a type which loyal obedience to the Prayer Book standards makes it of obligation that we should follow.

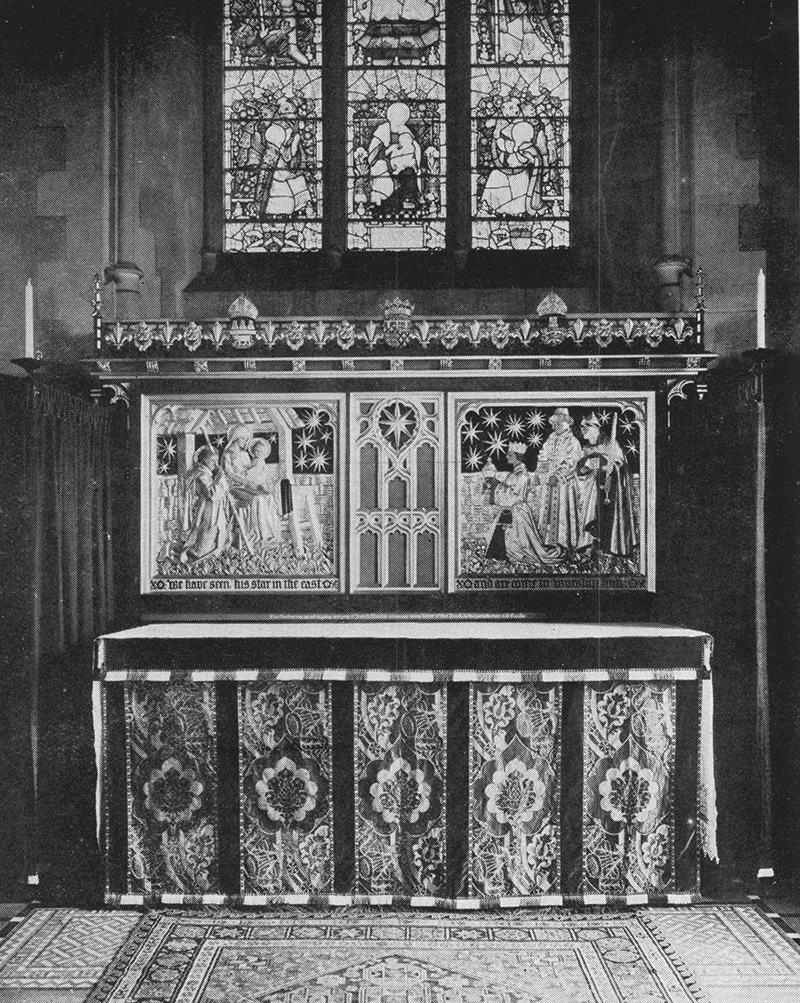

The examples of recent work here illustrated will serve to show how the Warham Guild gives expression to the principles which it maintains.

The high altar reredos at Princes Risboro’ designed by Mr. George Kruger Gray presents the adoration of the Wise Men in two panels of carved oak, gilded and coloured, divided by a smaller traceried panel showing in its head the guiding star. Above, there is a cornice and cresting, in which shields of arms are introduced with admirable effect. The lines of the riddel-posts are simple, and bear sconces with tapers. The riddels are of blue silk, hung from red cords. The frontal is of blue-and-gold tapestry, paned with a plain blue; the frontlet is narrow, as it always should be if the apparent length of the altar is not to be diminished, and it has a spaced fringe.

The Lady Chapel of the same church is rather narrow, limiting the length of the altar, also designed and painted by Mr. Kruger Gray. The reredos has in its middle [6/8] panel Christ reigning from the tree. The figure and the cross are of gold, upon a background of red, with lines of blue on the inside of the cope. Three panels on either side are decorated in colour and gold, and exhibit a scroll with the legend ‘Who Himself bare our sins in His own Body on the tree.’ There is no altar-cross, since the subject of the reredos makes one unnecessary; the candlesticks are kept low, and are set on the mensa. The frontal is of blue, paneled with red, black and gold tapestry; the riddels are of red, and hang from blue cords; and the riddle rods and sconces are of wrought iron.

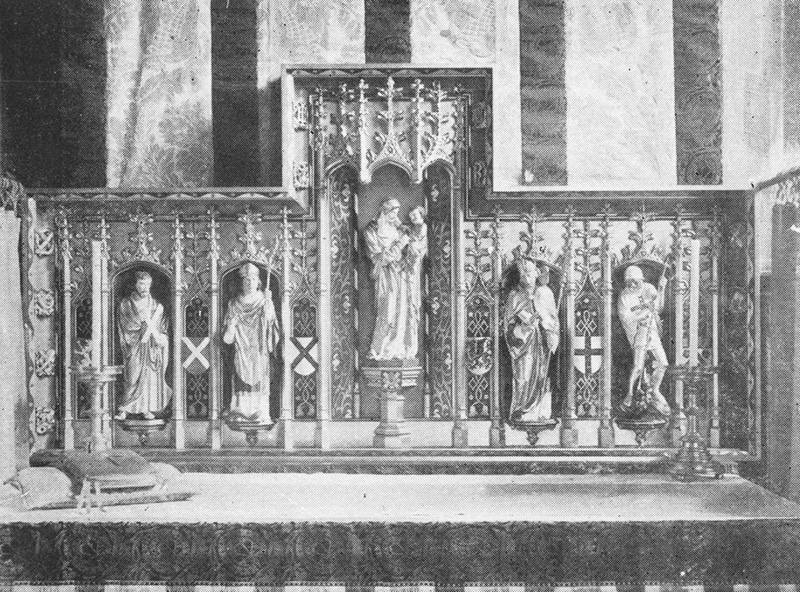

[10] The reredos for the altar in the Lady chapel of Bury parish church has five niches, of which the middle one is stepped up in a manner very customary in mediaeval examples. Mr. F. E. Howard’s design shows our Lady and the Holy Child; the other figures are St. Andrew, St. Patrick, St. David, and St. George. A free use is made of shields of arms and heraldic charges in the details. The reredos is of oak, decorated in gold and colour; the figures have gold robes with under-robes of blue, green, or red, with the exception of St. George, who, over his silver armour, wears a surcoat of white with the rosy cross.

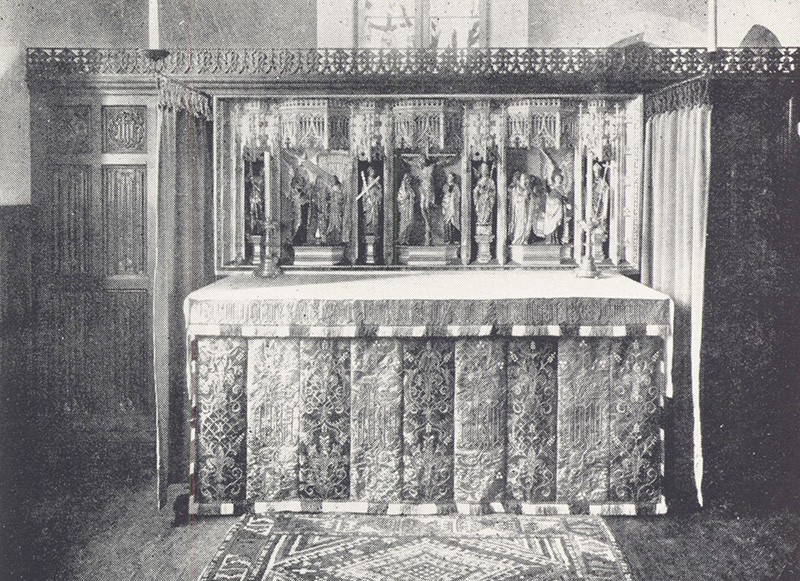

[11] The chapel at Merrow shows how exceptional circumstances can be successfully met. The narrow window, the doorway and recess in the wall, made this chapel a difficult problem; therefore a screen was erected forming a convenient little sacristy with a door on the south side behind the altar. The reredos, set in front of the screen, is decorated in gold, blue, and black, and contains three carved panels of the Annunciation, Crucifixion, and the three Maries at the Sepulchre. The four figures represent St. George, St. Andrew, St. Patrick, and St. David. Wrought iron rods support blue riddels; the frontal, of equal panels of green and blue silk, is embroidered in gold, and shows a wide spaced fringe, and there is a narrow blue frontlet.

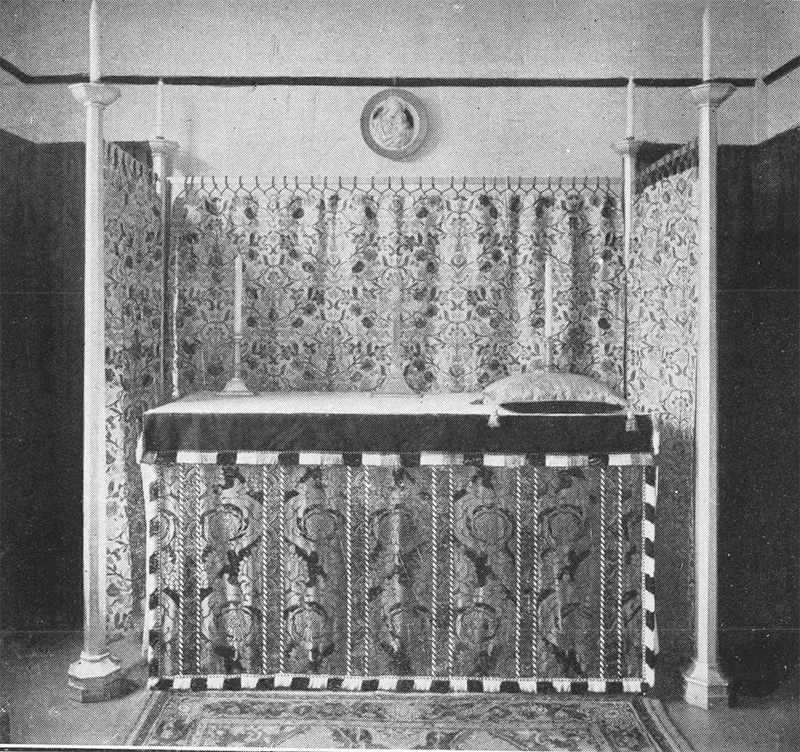

An altar in the showroom of the Guild demonstrates the effective use of simple materials. Here the dorsal, or upper frontal, and the riddels are of one tapestry, the nether frontal of the altar is of two woven fabrics paned, the riddel-posts could not be simpler. Yet dignity has been secured by the right use of what is available, and by just proportions. The ornaments do not distract attention, as do so many modern examples, from the altar itself; and on the altar there is a cushion for the book, such as was invariably used before the unhappy invention of glittering brass desks.

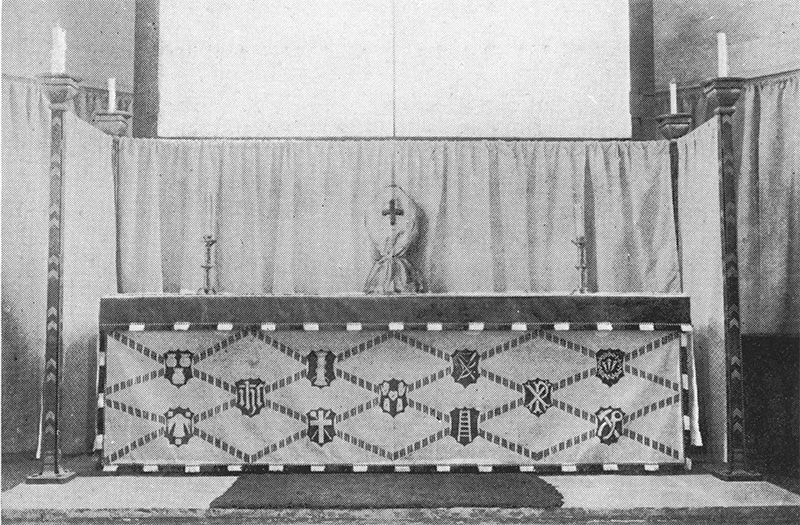

The last example is of an altar in its Lenten array as designed by the Rev. E. E. Dorling. The cross is veiled, the frontal is stencilled with shields in red, bearing emblems of the Passion; and the upper frontal [11/12] and riddels are of cream figured linen. It must be remembered that the Lenten white of the old uses had no relation to festal white, but was merely the suppression of all colour, the reduction of the ornaments of the church and the minister to the tone of the whitened walls of the medieval church.

The High Altar at St. Mary’s, Princes Risboro’.

The Altar in the Lady Chapel, St. Mary’s, Princes Risboro’.

Reredos in Lady Chapel, Parish Church, Bury.

Memorial Chapel, Merrow.

Dorsal, Frontal, and Riddels. (Simple materials with effective results.)

Small Altar in Lenten Array, St. Mary’s, Primrose Hill, N.W.