FAR up in the north of England, near where is now the town of Sunderland, Bede was born, in the days when the Northumbrians had been lately brought under the sway of Christ. The peaceful monks had settled in the country, to live a Christian life in the midst of the people, and to teach the little children all the knowledge they had gathered in the long quiet hours of study. Luckily for Bede, there had come to live in those parts, just about the time when he was born, a great and wise man called Benedict Biscop, who built two abbeys, Jarrow and Wearmouth, which he filled with such beautiful things as had never before been seen in England.

When he was only seven years old, the little Bede was taken to Jarrow monastery to be taught. And there he lived all the rest of his life. He was, it seems, of lowly birth; for nothing is told us of his parents. He did not travel, or fight, or govern; and his life would have been soon forgotten, like the lives of thousands of good men like him, had it not been for Benedict Biscop, who had filled the two sister abbeys with famous books, and taught the boy how to read and understand them. In no other place could Bede have found so many books, and nowhere else was there such a learned and enthusiastic teacher as Abbot Benedict.

So the gentle, studious lad worked early and late among the great volumes till he became cleverer than all the rest, and was thought so much of that he was ordained a deacon when he was only nineteen years old.

He remained a deacon for eleven years, working in the abbey-farm, in the garden and the kitchen, winnowing the corn, tending the lambs, baking the bread, teaching the little boys in the school, and in every spare moment reading his beloved vellum manuscripts. Though it was a quiet life, and one day went by much like another, there was not much rest for his busy brain. But he always found time for the long services in the chapel. "When the angels come to see the brethren as they sing in the congregation," he said, "What if they should not find me among the rest? They would say, Where is Bede? why does he not come with his brothers to the prayers?"

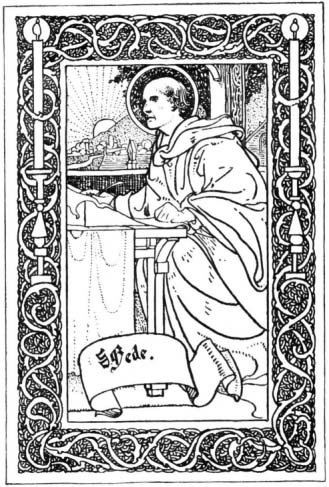

At thirty-one he was ordained priest, and then he began to make use of all the knowledge he had gained. I suppose his abbot let him off a good deal of the ordinary work at this time; for before he was an old man he had written about a hundred and fifty books, more than any Englishman had ever written before. It was a huge task; for he had no secretary, as he tells us, and no librarian, but made all his own notes, and then wrote them out slowly and carefully. There were no printers, either, in those days to make a neat book out of untidy writing; but what the author wrote down was what others had to read.

Most of all he gave himself to the study of the holy Scriptures, and so most of the books he wrote were commentaries on the Bible. These, however, are lost, and what has made Bede famous wherever the English language is spoken is his account of the beginnings of our nation. He wrote the first great English history book.

To this history we owe nearly all we know of Christian England, its saints and rulers, up to Bede's death. To it he gave the greatest labours of his life. For he spared no pains to make it interesting, and he sent messengers to the bishops and abbots all over England, so that he might leave out nothing that was important, and might be certain of the truth of all that he wrote.

What poor creatures we should be, if, like the animals, we knew nothing about the things that happened before we were born! How dull and foolish we should be if all the past were hidden to us! Yet, if it were not for Bede, and those who came after him, we should not know how our nation grew up and became great; we should not understand the religion that has made us what we are; and we should never have heard about the noble lives that show us what we ought to be.

The six hundred monks of Jarrow and Wearmouth looked up to the Venerable Bede as the pride of their abbeys, and loved him as their father, though he always remained a simple monk like themselves. But when he was only a little over sixty, he fell ill, one Passiontide, and they saw that he must soon die. How fondly they watched over him!

One of them has left us an account of these last happy days.

For five weeks, he tells us, our father and master grew weaker and weaker, and had great difficulty in breathing, though he suffered little pain, and was cheerful and happy, giving thanks to Almighty God, day and night, and every hour. He read us our lessons, just as if he were well, and spent the rest of the day singing psalms. Each night he lay awake in joy and thanksgiving; and sometimes he would have a short sleep, and then wake up again and give thanks to God with outstretched hands.

Never had I ever seen a man so earnest in thanking God. He chanted for them passages from Holy Writ, warning us to think of our own last hour, and he said also some things to us in poetry:--

Before the journey

Which all must take,

Nothing is wiser

Than to consider,

Ere the soul goes,

What it hath done

Of good or evil,

And how after death

It judged will be.

He also sang anthems for us. One of which is:--

O King of glory, Lord of all power,

Who, triumphing this day,

Didst ascend above all heavens;

Leave us not orphans,

But send upon us the Spirit of Truth,

The promise of the Father. Alleluiah.

But when he came to that word, "leave us not orphans," he burst into tears, and we mourned with him. By turns we read, and by turns we wept; nay, we wept always whilst we read.

In such joy we passed the days of Lent. And all the time he laboured hard to finish two works which he had begun. For he said, "I will not have my pupils read what is untrue, and work to no purpose when I am gone."

One of these was a translation of the Gospel of St. John. On the Tuesday before Ascension Day he became much worse, but all that day he dictated cheerfully, saying every now and then, "Go on quickly, for I do not know how long I shall hold out, nor how soon my Maker will take me away."

Next morning, the eve of Ascension Day, he ordered us to go on writing with all speed. And, while the rest had gone to walk in the Rogation procession, one of us said, "Dearest master, there is still one chapter wanting. Will it trouble thee to answer any more questions?" He answered, "It is no trouble. Take thy pen and make ready, and write fast."

At three o'clock he said to me, "I have some little articles of value in my desk, such as peppercorns, napkins, and incense. Run quickly and bring the priests of the monastery to me, that I may distribute among them the gifts which God has bestowed on me. The rich in this world give gold and silver and precious things; but I with joy give my brothers what God has given me." He spoke to each of them, and asked them to pray and say Masses for him, which they promised; but they all mourned and wept, especially when he said they should see his face no more in this world. "It is time," he said, "that I return to Him who formed me. I have lived long; the time of my dissolution draws nigh, and I desire to be dissolved and be with Christ."

He passed the day joyfully, till the shadows of the evening began to fall, and then the boy who was writing down his translation of St. John said, "Dear master, there is yet one sentence to be written."

He answered, "Write it quickly." Soon after the boy said, "The sentence is finished now."

"Thou hast well said, it is finished! Raise my head in thy hands; for I want to be facing the holy place where I was wont to pray, and as I lie to call upon my Father."

And so he lay on the pavement of his little cell, singing, "Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost." And when he named the Holy Ghost, he breathed his last, and so departed to the heavenly kingdom.

There is a story (which you won't understand unless like Bede, you have learnt Latin) that soon after his death, one of his pupils sat down to compose an epitaph for his tomb. He had written as far as this--

Hac sunt in fossa

Bedae ossaHere are in this tomb

Bede's bones

but he could not think of a word that would fit into the line, for a word like sancti (saint) would have spoilt the metre. And so, much troubled, he got him to bed. Next morning he went to his task again, and found that an angel had put in the word that was wanted--

Hac sunt in fossa

Bedae Venerabilis ossa.Here are in this tomb

Bede the Venerable's bones.

So this saint has ever since been known as the Venerable Bede.