IN 1840, an Indian catechist (now the Rev. Henry Budd), in the employment of the Church Missionary Society, commenced the first Mission, now called Devon Mission, on the Saskatchewan River. He met with signal success. When, after two years, a clergyman went out from Red River to visit the new Mission, he found about ninety converts from heathenism prepared for holy baptism; and in 1844, when Archdeacon Hunter took charge of this Mission, he had the pleasure of baptizing, on the Sunday after his arrival, thirty-one adults and thirty-seven children.

Some of the Indians of Stanley, which is in the neighbouring English River district, having visited Devon, carried back to their tribe what they had heard from the Missionary. The Gospel, thus introduced, soon obtained a firm footing. This was mainly due to the efforts of a Devon Indian, long gone to his rest, but whose memory is still warmly cherished at Stanley. Though without education--he could not read--he was so filled with warm love for Christian truth, that he knew by heart whole chapters of God's Word. He visited Stanley, and travelled about among the Indians, teaching them the way of life, and hunting for his living at the same time.

In 1846 the Rev. James Settee, an Indian clergyman, then a catechist, was sent to Stanley to prepare the way for a Mission. He found everything ripe; and when Archdeacon Hunter visited the place in the following year, he was able to baptize most of the Rapid River Indians near Stanley. Two or three years later the Rev. R. Hunt and Mrs. Hunt arrived, and commenced their earnest and devoted labours.

The site of the first station was on Lac la Ronge, a lake so named by the French voyageurs, from the number of willows and trees about its shores peeled and gnawed by beavers. These industrious little animals [34/35] 1are now comparatively scarce. The trade in furs has caused their destruction, so that a peeled willow is not now often seen along the shores of Lac la Ronge. The lake is about fifty miles in length, and nearly the same in width. Only about one-third is an open lake, the greater part being full of islands, nearly all thickly wooded, except where fires have destroyed the trees. The lake abounds with white-fish and trout, besides other kinds of fish. After a few years, however, it was thought desirable to remove to the English River, where the station called Stanley is now located.

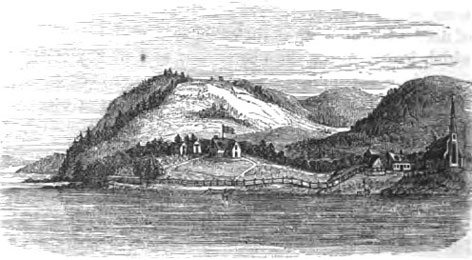

The present site is about forty miles from the old station by a nearly straight road, and stands on a point formed by a bend of the English River. This river has the appearance of a series of lakes. It narrows at intervals, and at such places there is almost always a rapid, or waterfall. The wide parts of the river are full of islands, and indented with numerous bays. Stanley is situated at the end of one of these lakes. The country around is rocky and hilly. The point occupied by the won-station is comparatively level, but rocky: hills rise up immediately behind. One of these, which forms a rocky precipice on the side washed by the waters of the lake, is known as the shooting rock. It was a superstition of the Indians that a spirit had his abode in this rock, and that any one who could shoot an arrow to the top of the rock was sure of a long life. The Christian Indians no longer believe in such childish superstitions; but only a few years ago there were still many arrows to be seen on the top of the rock.

The most conspicuous object that meets the eye of the visitor to Stanley is the church, which stands on the extremity of the point of land on which the Mission-station is built. It is generally considered to be the most beautiful in Rupert's Land; and only one who has experienced the difficulty of getting any building erected, where there is an almost total want of skilled labour, can form any adequate idea of the difficulties with which Mr. Hunt had to contend in erecting this beautiful structure, with its nave, aisles, and chancel. He who built it did it for the glory of God, and spared neither effort nor private means to carry out the work.

To the rear of the church stands the school-house, a substantial frame building, about thirty-two feet by twenty-two, whitewashed on the outside, and lined with pine boards, with shingled roof.

A little on one side is the workshop and fisherman's dwelling, a log building, with thatched roof. A little above, and separated from these by a field, stands the Mission-house, a neat but rather small building: some little distance in the rear of the parsonage stands the barn and stables. At the end of the barn is the great mill, worked by horsepower. Below the Mission premises are a few cottages, occupied by Christian Indians. The station is also furnished with a small printing-press, with syllabic types, with which the present Missionary, Mr. Mackay, [35/36] a native of the country, prints books in the Indian language, which he also most neatly binds.

Although Stanley is so far north, its climate is not unfavourable for agriculture. Wheat, since it has been fairly tried, has ripened for six years in succession. Barley and potatoes are a sure crop, and also most of the common garden vegetables. Indian corn sometimes comes to maturity, but cannot be depended upon. The winter is longer than at Red River, in the. Province of Manitoba, but the cold is not much more severe. The dryness of the atmosphere, and the shelter afforded from storms by the numerous hills, render the cold of winter more bearable than in many other parts of the country.

The Mission farm lies around the Mission buildings. The gardens of the Indians are situated, for the most part, on islands in front of the station.

But the Indians of Stanley still follow their original patriarchal mode of life, living in tents of skins, and, both in summer and winter, moving about from place to place. They procure their food chiefly by fishing and hunting, and their clothing by barter for furs and skins. The time, however, may not be far distant, when the Missionary may see it his duty to attempt to lead them to a more settled life.

Church organisation has been carried forward at Stanley as far as the peculiar circumstances of the congregation admit. There are native churchwardens and vestrymen, and considerable interest is manifested in Church matters. There is an offertory four times a-year, to which the people give according to their ability. The offerings are not in money; for coin is not the medium of exchange in this part of the country. The Indians give skins, leather, mocassins, meat, work, or anything of the kind. They bring their offerings to the Missionary, and receive a ticket for the value. These tickets are collected by the Indian churchwardens in the church, at the proper time. The offerings exceed £20 a-year.

The male Jews were commanded to appear before the Lord three times yearly at Jerusalem. Our Christian Indians, men, women, and children, at Stanley, appear, as a rule, four times a-year, namely, at Christmas, Easter, and on two other occasions. In the spring and autumn they arrive in the little canoes, often quite a little fleet at a time. The men come alone, each in his little hunting canoe--a little affair, so light that he can carry it on his shoulder almost any distance; the women, in larger canoes, with their tents, their children, and the greater part of their effects. In winter they arrive on snow-shoes, their tents and other things being packed on flat sleds, which are drawn sometimes by dogs, and sometimes by themselves.

Among heathen Indians the woman is usually the beast of burden; but among the Christian Indians the women are better treated. The men generally take the load, if there are no dogs to draw it; and the [35/36] woman's burden is ordinarily the baby, slung on her back in an Indian cradle. They come from all directions, as their hunting-grounds lie on all aides. Suppose England were a wilderness, inhabited by seven or eight hundred people scattered over its surface, with a Mission-station in its centre: that is a picture of Stanley. Many of the Indians come to the station from hunting grounds more than a hundred miles distant. As long as they stay, the church is filled morning and evening with an attentive congregation. The Word is preached not only every Sunday but every day, as long as the Indians continue at the station. They remain commonly as long as the supplies of food which they have brought with them last, which may be for a few days, or for some weeks, and then they travel off again until another gathering-time comes round.

The Missionary says that the Sunday when the Holy Communion is celebrated is always marked by peculiar solemnity. The daily evening lectures throughout the week previous are always intended to lead the hearers to a due preparation of heart and mind. There is at all times a spirit of inquiry manifested. The Missionary has frequent visits at his house, to ask explanations of something read or spoken in the church, which has not been quite understood. One of the churchwardens is generally deputed to ask the information. This spirit of inquiry is always more manifested during the week before Holy Communion than at other times. On Saturday evening the address has always special reference to the Communion. It is generally intended to be a warning against mere profession. The whole body of the communicants attend, as all are required, according to the Rubric in the Prayer-Book, to give in their names the day before, and immediately after service on Saturday evening the names are taken down. On Sunday morning the singers assemble to sing over the hymns for the day. In the forenoon there is the usual service, as the Communion is in the afternoon. The sermon is generally intended to stimulate to fresh efforts in the Christian cause.

Between morning and evening service is the Sunday-school. On such occasions, when all the Indians are at the station, the number of scholars is generally from fifty to sixty. As many of these are seldom under instruction, they have to be dealt with according to the extent of their knowledge. The chief aim is to follow the requirements of the Church in the Baptismal Service. The children are arranged in classes, according to their knowledge. Reading and writing are left for weekdays. On Sundays the lowest class is taught the Lord's Prayer, although it is generally only the very little children who are not able to repeat it. The next learns the Creed, the next the Ten Commandments, and another class the whole Catechism. There is, besides, a Bible-class of young men and women. The lower classes are taught by teachers [37/38] selected from the most capable of the young men and women who attend, while the Missionary himself takes the Bible-class.

After school the congregation again assembles. The service is simply the Communion Service, with the Offertory. The sermon is intended to set forth the privileges of true believers. At the Holy Communion much feeling is often manifested: almost always some approaching and kneeling down in tears. The Sunday closes with a meeting in the school-room for devotional singing; and the exercise is closed with reading a portion of God's Word, and prayer. The meeting for singing is very much enjoyed by the people.

In a district where the population is so scanty and Missionaries so few, the Missionary's efforts cannot be confined to the station. At intervals of from 60 to 200 or 300 miles throughout the country are scattered the Hudson Bay Company's trading ports, which are centres to which the Indians resort for trading purposes. These ports the Missionary must endeavour to visit, although travelling both in summer and winter is attended with much inconvenience, and entails great loss of time. In summer, if the distance is not very great, he generally travels in a small canoe with one Indian. In winter, instead of the canoe, the conveyance is a flat sled, drawn by three or four dogs, laden with blankets and provisions for the journey. One man walks before the dogs. Sometimes, but very rarely, if the road is good, a little riding relieves the fatigue of constant walking. Generally the snow is deep, and if the sled is heavily laden, the Missionary or his companion has to assist the dogs by pushing the sled with a long pole.

Occasionally in these journeys Indians are met with, sometimes encamped in a picturesque spot, abundantly supplied with food, and otherwise sufficiently comfortable; but at other times, and particularly in winter, undergoing great privation. Last winter, on one occasion during a journey, the Missionary and his solitary companion had encamped on a small island in a large lake. Supper was over, and evening prayer, and they were about to lie down to rest, when the barking of the dogs told them that some one was approaching; and soon two men made their appearance out of the darkness, and stood by the camp-fire. They were two Stanley Indians, a father and son. They were in want of food, and they had left their tent long before daybreak to follow a herd of deer, but had met with no success. They were too far from their camp to think of returning that night, and they were about to encamp upon the snow without a morsel of food, when they saw the fire, and came in hopes of meeting with some one better off than themselves. It is needless to add, their immediate wants were abundantly satisfied.

There are still a few Indians in the neighbourhood of Stanley who only occasionally hear the Word of God, and who do not even make [38/39] a profession of Christianity. Among these the Gospel is making gradual progress.

Many cheering testimonies have been afforded from time to time by Stanley Indians of Christianity having given them a hope that maketh not ashamed.

About three years ago, Mr. Mackay, on reaching Isle à la Cross in the midst of the winter, found that one of the Stanley Indians had died there shortly before his arrival. His end had been very happy, as he was a simple follower of Christ. He bore his illness with resignation. His son-in-law, once hearing him weeping, inquired the reason, when he replied, "I am overpowered by the thought of God's mercy toward me." His last words were two lines of a Cree hymn--

About the same time an Indian, William Roberts, who had been a willing helper at the station, died. His death was very hopeful. He told his friends calmly that he was about to leave them, and gave directions for his burial, as the distance from Stanley, being five days' journey, was too far for the body to be conveyed to the station. He told his brother-in-law to read the Burial Service over his grave, and, as soon as he could, to proceed with his family to the Mission-station. Shortly afterwards he desired to be raised up, and while his sister and brother-in-law supported him he repeated distinctly the opening sentence in the daily service--"When the wicked man turneth away"--then the Collect for the First Sunday in Advent, and, lastly, the prayer in the Litany, "O God, who despiseth not the sighing of a contrite heart," &c. As he finished this prayer he breathed his last.

It is most touching to hear of such a realising of life with Christ, and such an entering into our Church's prayers in this distant Mission in the centre of Rupert's Land, far remote still from all civilisation. May we not indeed ask, with adoring wonder, what hath God wrought?

The present Bishop of Rupert's Land spent a most interesting week at Stanley in 1869, as his predecessor had done twice before. On this latter occasion about fifty were confirmed, after a careful and most satisfactory individual examination. The great proportion of the candidates could read their language in the syllabic character. Mr. Mackay has translated a Book of Family Prayer, published by the Bishop for the diocese into the Cree language, and also the "Pathway of Safety" of the Bishop of Montreal; He has also printed for them tracts, primers, prayers, and almanacks, and they have the Bible, the Prayer-book, and a hymn-book in the same character in their hands.

They are altogether a very interesting tribe of Indians, particularly gentle and teachable. As the Mission began from themselves, so they still do not a little themselves. It is a constant practice with them, when [39/40] they meet any of their heathen brethren in their wanderings, to endeavour to impart to them a little knowledge at least of the way of salvation. There had been, indeed, direct efforts made and journeys undertaken by more than one of the Stanley Indians to bring their heathen neighbours to a knowledge of the truth as it is in Jesus.

An effort of this kind about two years ago led to a sad accident. The Missionary asked one of the Christian Indians to go and visit a party of heathen whom he had visited a short time before, and had reason to believe were earnestly seeking the way of life. The old man consented at once to go; but, as he intended passing the winter with these Indians, he wished his whole family to accompany him. It happened that two of his sons were on a voyage in the Company's boats, and, the season being late, he started without them, leaving instructions that they should follow him. The two young men left to fulfil their father's wishes, and nothing more was heard of them; but, after the cold weather had fairly set in, their canoe was found turned over and frozen in the ice, and there could be no doubt of their sad fate, although no mortal eye had witnessed their last agony and struggle for life. When Mr. Mackay was made acquainted with the circumstance he went three days' journey to break the news to the bereaved parents; but was unable to find them, and they did not return to the station until near Easter. Some time after the old man came to Mr. Mackay, and expressed his intention of leaving again on the same errand, saying that his sore trial had only made him more desirous of bringing others to a knowledge of the Saviour. Mr. Mackay will be assisted this winter by a Stanley Indian, who has been at the College in Manitoba, for which the Bishop is asking assistance while he is now in England. This man, John Sinclair, was committed to Mr. Settee by his dying father in a remarkable way, to be dedicated to the Lord's service. He has been for some time a Catechist, and latterly has been at St. John's College. But his health gave way this summer, and he has returned for a time to his native air, to act again as a Catechist.

The preceding remarks are mainly in the words of the present Missionary at Stanley, himself a native of the country, partly of Indian descent. They tell the story of one of the many Missions now existing in Rupert's Land. Great as have been the triumphs of the Gospel in many parts of the world in this century, probably, when the difficulties of the work are considered, there are none more striking and signal than what have resulted from the labours of the Missionaries of the Church Missionary Society in that land.