ON June 25, the day after his Consecration, the new Bishop performed the first distinctively episcopal act of his life by ordaining to the priesthood the Rev. William Carpenter Bompas in St. Paul's, Covent Garden, London. Bompas had been curate at Alford in Lincolnshire, but had earnestly desired for some time to become a missionary abroad; he had already offered himself to the C.M.S. for work in the Orient, but the Society had thought him rather too old to learn the languages of the East thoroughly. It happened, however, that in 1864 he was present when a sermon was preached by Bishop Anderson, who appealed for a man to go out to Fort Yukon to relieve the devoted and heroic Archdeacon M'Donald, then ill and worn out with his hard and incessant labours in that remote and solitary post in the far north of Rupert's Land. Bompas, deeply impressed, immediately volunteered his services, and was accepted for their Fort Yukon mission by the C.M.S., who arranged with the Bishop of London, as diocesan of the See in which the ceremony was to take place, that his own Bishop, Dr. Machray, was to ordain him. He sailed from England without delay for America, and reached Fort Simpson, a mission on the Mackenzie River, after a journey of many months, to hear that M'Donald had recovered. From Fort Simpson he went to Athabasca, and he did not leave these far northern regions until he went back to London to be consecrated, in 1874, Bishop of Athabasca, one of the first dioceses to be carved out of the original Diocese of Rupert's Land. Of this great missionary a biography was published in 1908 by the Rev. H. A. Cody, under the striking and appropriate title, An Apostle of the North.

Bishop Machray did not leave for his See for some two months, employing the time in raising funds for his Diocese and in making necessary preparations. On the day of his Consecration he issued a printed statement which, besides asking for financial assistance, gave a description of Rupert's Land. For the purpose of aiding his efforts he had already formed an influential committee, which included the Bishops of London, Ely, and Ripon, the Bishop of Aberdeen, Bishop Anderson, Clayton, then Canon of Ripon and Rector of Stanhope, Darlington, Canon Selwyn, Canon Sale, the Rev. C. A. Jones, then Mathematical Master in Westminster School, the Rev. T. T. Perowne, now Archdeacon of Norwich, the Rev. W. Banham, the friend of Dr. Machray's Cambridge undergraduate days, and several others. He visited a number of centres, delivering addresses on behalf of Rupert's Land, but the time was too brief for much being done; he succeeded, however, in collecting £400 to which he added £100 from his own pocket. This result was not very good; its leanness was probably caused, not only by the shortness of time at his command, but also by the fact that few people knew, and still fewer cared, anything about Rupert's Land. He appointed as his Commissary the Rev. Charles Edward Oakley, Rector of St. Paul's, Covent Garden.

He had two long interviews with Prebendary Venn of the C.M.S., who urged upon him the desirability of seeking to make the missions self-supporting wherever it was possible, and of having native pastors for the Indian congregations; both were ideas with which he was in complete agreement. The heads of the other Church Societies expressed very similar views. Amongst other things, he heard that his episcopal residence, Bishop's Court, St. John's, had been allowed to get into a dilapidated condition after Bishop Anderson's departure, and that it was hardly fit for habitation; so much out of repair was it that shortly before he left England the C.M.S. offered to him the use of the parsonage of one of their missions, St. Andrew's, some miles distant from St. John's. In the meantime the clergy and people of his Diocese had been apprised of his appointment and Consecration, and informed that he would arrive amongst them in the end of September or the beginning of October.

Accompanied by his personal servant, Thomas Smith, a young fellow drawn from a Cambridgeshire village, who, in after years, became a member of the Legislature of Manitoba, he travelled by sea, and land, and river, until he arrived at St. Paul in the State of Minnesota, where he bought a horse and carriage with which he was to continue his journey from St. Cloud, the most westerly point to which a railway then ran. In those days the great American transcontinental railways did not exist, and St. Cloud was only a few miles from St. Paul, which, however, was not then fully connected with New York by railroad. From St. Cloud northward to the southern boundary of Rupert's Land there lay some four hundred miles of prairie, to be traversed by stage, or carriage, or waggon. While in St. Paul, however, he was met by Mr. Cohn Inkster, who had come from St. John's to guide him to his new home. Of the journey from St. Cloud, Mr. Inkster, now the Hon. Colin Inkster, formerly a member of the Legislative Council of Manitoba, and still Sheriff of Manitoba, has furnished the following graphic account:

It was in August 1865 that I was asked to take charge of a party going to meet the Bishop at St. Cloud, Minnesota, which was then the terminus of the St. Paul and Pacific Rail road, and to bring him with his luggage to that part of Rupert's Land known as the Red River Settlement, in which were his Cathedral and his residence, Bishop's Court. I had three men, six horses and carts, and a couple of spare horses. We arrived at St. Cloud about the middle of September, and had to wait about ten days for his arrival. Meanwhile I took the train to St. Paul, where I met him. I shall never forget the first impression the Bishop made on me. Although I was only a mere lad, I could see he was no ordinary man. He was tall and thin, with a jet-black beard and piercing black eyes. The reverence which he then inspired in me went on increasing as long as he lived.

We were kept waiting in St. Cloud much longer than we had expected, but as soon as we were ready we made a start; it was on a Friday, and it might, but for an all-ruling Providence, have proved a very sad day for us all. We intended to drive about twelve miles to a village called Cold Spring. We had not been on the road half-an-hour when a tremendous storm, with thunder, lightning, wind, and rain, came upon us. It was impossible to pitch a tent, so I advised the Bishop to drive on to Cold Spring and stay the night there in a hotel. The village was built on the side of a hill, and across the road, quite near it, was a "wash-out" some ten to twelve feet deep, which had been made by the storm; it was too dark for us to see what had occurred, and we knew not our peril; even at this distant date it is frightful to think of it. Just as the Bishop's horse was within a few feet of the chasm a flash of lightning showed it to him, and, at the same time, revealed a few yards on the hotel where he was to stop. A few seconds more, and without doubt the Bishop and his man, who was with him, would have been instantly killed but for that flash of lightning.

After this hairbreadth escape our experiences were entirely pleasant; we had no more rain for the rest of the trip, and the weather was perfect all through. We shot all the ducks, geese, and prairie chickens we could use, also some swans and a black bear. The Bishop had brought with him a shot-gun and a rifle, but he never fired a shot. One of my men, Joseph Monkman, junior, who was commonly called "Foolish Joe," cooked for the Bishop and looked after the tent in which he camped on the way, and a better man for that kind of work could not have been got anywhere; he had had a large experience in similar work for gentlemen of the Hudson's Bay Company. The Bishop was so pleased with him that he took him along in the same capacity in the following winter when he made his first Visitation by dog-sleigh. Every night of our trip the Bishop read a portion of Scripture, sang a hymn, and said a prayer. I remember the first night in camp he read and expounded the First Psalm.

Our progress was slow, so when we were about fifty miles south of Pembina, a post on the international frontier where the United States had a detachment of troops, and the Bishop showed some anxiety to get along faster, I took a horse and light waggon, with enough provisions to see us home, and leaving the rest of the party to follow more leisurely, pushed on with the Bishop who was driving his own horse and carriage. At noon, on October 12, the day after we left the others, we reached the Hudson's Bay Company's post, at Pembina on the British side of the frontier, where we found fresh horses. In the course of the next day, October 13, we crossed the Assiniboine River, passed under the walls of Fort Garry, and through the little hamlet rising round the Fort, now the great and growing city of Winnipeg.

When we arrived at St. John's, two or. three miles from the. Fort, we were welcomed by the ringing of bells from the tower of the Cathedral, and two of his clergy, the Rev. Abraham Cowley, a C.M.S. missionary (afterwards Archdeacon of Cumberland), and the Rev. W. H. Taylor, a missionary of the S.P.G., warmly greeted their Bishop, who, finding that Bishop's Court had been repaired and made habitable, took up his abode there. Some days later the rest of our party came in, bringing the goods and chattels which the Bishop had conveyed with him from the old country. I can remember the first sermon the Bishop preached; his text was, "He that winneth souls is wise."

The fortnight's journey across the prairies had been very pleasant, and formed an agreeable initiation into life in the North-West. It had, however, been a some what costly trip--£125, but this sum included both travelling expenses and the transportation of the cases and boxes of supplies, books, and other articles that he had brought with him from England. When he reached the Settlement he found that he had spent the whole of his first year's income as Bishop, £700, on necessary things, their carriage to the country, and his travelling expenses. On taking up his residence at Bishop's Court he invited the Rev. W. H. Taylor, who was Incumbent of St. James's Church, to live with him for the winter as his Chaplain, and Mrs. Taylor also to manage the establishment. He at once took charge of the Cathedral parish of St. John, and per formed all the duties in connection with it of a simple parish priest.

These opening days of his episcopate were darkened by sad news. As he came into the district he heard that Archdeacon Cochran, the leading clergyman in the Diocese, who had spent forty years of incessant and successful missionary labour among the settlers and the Indians, had passed away at the beginning of the month, and the first letters he received on his arrival told him of the sudden death of the Rev. C. E. Oakley, of St. Paul's, Covent Garden, whom he had appointed his Commissary a short time before leaving for Rupert's Land. He wrote to his friend, the Rev. T. T. Perowne, and asked him to take up the Commissaryship--to which request Mr. Perowne gladly consented as a "labour of love."

At this point it is convenient to give some account of Rupert's Land: first, as regards its history generally; and, second, as regards the history of the Church of England in Rupert's Land prior to the Bishop's arrival in the country, of which, by the way, Sheriff Inkster's narrative has already given some incidental glimpses, for the prairie regions of Minnesota and other adjacent states scarcely differ from those of Rupert's Land, the boundary between them being purely artificial.

The name of Rupert's Land has vanished from all save ecclesiastical maps, and to-day survives as a designation in common use, and that only over a restricted area, solely in the names of the Diocese and of the Ecclesiastical Province of Rupert's Land. The present Diocese, which includes the greater part of Manitoba, covers but a small portion of the original See; the Ecclesiastical Province, however, consists exactly of the old-time Rupert's Land. In 1670 Charles II. granted a charter to the "Governor and Company of Adventurers trading into Hudson's Bay," by which they were given certain rights over an enormous extent of territory in North America. The country was then practically terra incognita, but the royal Letters Patent decreed that it was to be "reckoned as one of the king's plantations and colonies in America called Rupert's Land," and the name was conferred upon it out of compliment to Prince Rupert, the gallant and dashing nephew of Charles I.

The "Adventurers" came to be known simply as the Hudson's Bay Company, and for two centuries they controlled, though not always without dispute, the whole of what is now the Dominion of Canada, with the exception of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime Provinces on the Atlantic seaboard, an area of about three million square miles. Their main business was the prosecution of the fur trade with the various tribes of Red Indians who inhabited the interior, but they also exercised judicial and administrative powers over the territory. In the course of time rival fur companies were formed, the principal being the North-West Company of Montreal, but after much bitter strife and some bloodshed the Hudson's Bay Company succeeded in destroying or absorbing all their competitors. As late as 1816 a battle was fought at Seven Oaks, the name of a piece of land just outside the city of Winnipeg, between the employees of the Hudson's Bay Company and of the North-West Company, in which Governor Semple, the head of the former, was killed, while twenty-one of his followers were killed or wounded. The two companies were amalgamated a few years afterwards. It was, no doubt, in a way a fine, stirring, picturesque time, full of incident and colour.

Naturally enough the Hudson's Bay Company not only sought to destroy their rivals, but discouraged the formation of settlements as likely to be hostile to their interests as merchants and traders in furs, the monopoly of which they maintained was their exclusive right. However, Thomas, fifth Earl of Selkirk, a Scottish nobleman and a large shareholder of the Company, got to know of the fertility of part of the country, and came to the conclusion to settle on the banks of the Red River of the North a number of Highland small farmers and peasants, who had been dispossessed of their holdings in Sutherlandshire. The project was carried out, and in 1812-14 the first settlers arrived in the district he had selected, and the settlement was known as the Selkirk Settlement. Other settlers of the same class followed, but for several years the story of the Settlement was one of disaster, owing partly to the feuds of the rival fur traders, partly to floods and plagues of grasshoppers or "locusts," and partly to its isolation from the rest of the world. After a time it became fairly prosperous.

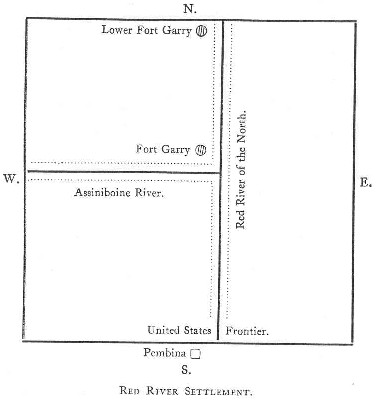

The Selkirk Settlement was strung out for some miles on both the west and east banks of the Red River, which flows northwards into Lake Winnipeg, the most southerly of the farms being about three miles from Fort Garry, an important post of the Hudson's Bay Company, situated at the confluence of the Assiniboine River with the Red River. Some twenty miles lower down the latter stream stood another post of the Company, called Lower Fort Garry, also known as the Stone Fort. As time went on land was gradually taken up between the two forts by settlers other than the Selkirk settlers, and along the Assiniboine west of Fort Garry, and the Red River south of that fort, until one line of settlement, perhaps a hundred miles in length, lay within the northern angle formed by the junction of the two rivers, while a second and similar line was included within the southern; a third line stretched along the east bank of the Red River for some sixty miles or more. In the subjoined diagram the dotted lines represent the lines of settlement.

To the comparatively small part of Rupert's Land thus colonised was given the general appellation of Red River Settlement. In 1835 it was organised by the Hudson's Bay Company for purposes of administration as the "District of Assiniboia," with a local Governor and Council. The Governor was the chief officer of the Company, and he had his headquarters at Fort Garry, which became the centre of the Settlement. Earlier the North-West Company had had a post called Fort Douglas, about a mile away on the Red River, but on the amalgamation of the two companies in 1821 this post was abandoned, and Fort Garry was built, to be replaced by a much larger and stronger Fort Garry in 1835. The Council of Assiniboia was composed of fourteen of the leading clergy and laymen of the place, who were nominated by the Governor and not elected by the settlers. When Bishop Machray arrived in the Red River Settlement in 1865, Mr. William Mactavish, then Governor of Rupert's Land as well as of Assiniboia, at once appointed him a member of the Council.

For many years this system of government worked well enough, but as the population increased there were manifest signs that it was breaking down. The difficulty was that it had no adequate means of enforcing its decisions, and when criminals "broke gaol," as sometimes happened, there was no machinery for recapturing and punishing them. Finally, this state of things led to scandals which gravely compromised the central authority, and helped to make more serious and menacing the Rebellion which broke out shortly before the close of the Hudson's Bay Company's régime. Besides, men accustomed to elect their own representatives came into the Settlement and excited discontent with the manner in which the Council was chosen.

In 1835 the population of the Settlement was about five thousand; by i 86 it had grown to about eleven or twelve thousand, of which number only a few hundreds were of pure white extraction, the rest being English, Scotch, or French half-breeds--people with some proportion of Indian blood in their veins. In addition to the Selkirk settlers, the population of Assiniboia (which must not be confused with the later Canadian Territory of the same name) consisted of retired officers and servants of the fur companies, and of other settlers who had come into the country from Canada, the United States, and Europe, to hunt and trap, to farm, or to "trade." Not a few of them were engaged in "freighting," that is, in the carriage of merchandise across the prairies in carts from one point to another, as, for instance, from St. Cloud in Minnesota to Fort Garry, a slow and toilsome occupation, and sometimes dangerous because of marauding Indians out on the war-path. in the neighbourhood of the Settlement, and within the Settlement itself, were several bands of Indians, mostly Crees and Assiniboines, and scattered over the whole of Rupert's Land there were many tribes, mostly nomadic within certain wide areas, their total numbers being estimated at 60,000. They lived by the chase, exchanging the skins of the animals they killed with the fur traders for guns, powder and shot, blankets, and other commodities.

The wise and paternal policy of the Hudson's Bay Company had made the Indians of Rupert's Land for the most part friendly to the whites and to the settlers in Red River. South of the international boundary, but yet close to the Settlement, a very different state of affairs prevailed. On the American side of the "Line,"--a line, an imaginary line is all the boundary is--there lived the fierce and warlike Sioux, who, only three years before Bishop Machray reached Red River, had perpetrated a series of frightful massacres, in which fifteen hundred Minnesota settlers were killed, after being subjected to indescribable tortures. In 1865 the Sioux were still a menace.

In the biography of Bishop Bompas, referred to in the first paragraph of this chapter, it is stated that when Bompas and his party arrived at St. Cloud, a few weeks in advance of Bishop Machray, they were told that since the fearful Sioux massacres of 1862 "the people were in great dread all over the country," and they "found it impossible to get any one to convey them to Red River. After much trouble and delay they were forced to procure a conveyance for them selves. Before leaving St. Cloud they were told time and again to beware of the Indians, who were always prowling around." It was suggested to them that they should take some British flags with them, as the Sioux respected the Union Jack, and they accordingly bought some; the rage of the Sioux was directed against the "Americans," not the English. And on their journey a band of Indians in full war-paint was seen in the distance, and one "brave" galloped forward towards them and reconnoitred, but when he saw the British ensign he rode off and rejoined the band of painted warriors, who thereafter quickly disappeared.

The inhabitants of the Red River Settlement lived in a very primitive, in almost a patriarchal fashion. Most of the heads of families had a long narrow strip of land fronting on one of the two rivers; a few of the houses were of stone, all the rest were of wood--generally roughly-squared logs of oak or elm, with the interstices in the walls filled in with mud and lime. They cultivated no more of their land than was sufficient for their subsistence; they had flocks and herds of no great size; the inaccessibility of their country, and the absence of markets--the nearest in those days was hundreds of miles away from Fort Garry--deprived them of all inducement to attempt more than was absolutely necessary to support life in some sort of rude comfort. Near Fort Garry there were a few houses and stores, chiefly of "Free Traders," as those were termed who were engaged in the fur trade in opposition to the Hudson's Bay Company, but Winnipeg can hardly be said to have come into existence when the Bishop reached Bishop's Court; there was not a butcher, baker, tailor, or shoemaker in the whole land, he wrote soon after his arrival. In the last years of his predecessor, Bishop Anderson, the isolation of the Settlement had become less; a stern-wheel, shallow, flat-bottomed steamer ran for a year or two on the Red River during summer, and regular communication was opened up with St. Paul in Minnesota. But the Sioux massacres drove the steamboat-men away, and interrupted the river traffic for several years, though afterwards the steamers once more appeared. In the early days of the Settlement communication with the outside world was so difficult and costly as to be almost impracticable. Once a year the Company's ships came into Hudson's Bay with goods and supplies from England, but these the Company mostly required for their own purposes, and, in any case, hundreds of miles of wilderness intervened between the Company's factory on Hudson's Bay and Fort Garry in the Red River Settlement.

And if it was difficult for any one or anything to get into the country, it was practically impossible for any one or anything to get out of it, unless the Company were willing; and the Company, not being general carriers, were never too willing. Ingress and egress became easier only when the American trans continental lines of railway were being constructed; but the nearest, as has been seen, was more than four hundred miles to the south of Fort Garry as late as 1865. In such a community there could be no great wealth, but the people were, on the whole, happy and contented. Where the French element predominated there was greater liveliness of disposition, where the English or Scotch greater intelligence; but, speaking generally, the settlers got on very well together, with much freedom of intercourse and profuse exchange of hospitality, especially in the long, cold winters.

Among the instructions given by the Hudson's Bay Company to their officers was one to the effect that the Liturgy of the Church of England was to be read regularly at all posts of the Company, but for a century and a half there were neither churches nor schools in Rupert's Land. In 1815 Governor Semple wrote: "I have trodden the burnt ruins of houses, barns, a mill, a fort, and sharpened stockades, but none of a place of worship, save on the smallest scale. I blush to say that throughout the whole extent of the Hudson's Bay territories no such building exists."

The first cleric to appear in the country was Père Messager, a French-Canadian priest, who in 1731 accompanied the Sieur Varennes de la Vérandrye into Rupert's Land, but he established no mission that endured; in 1818, however, two Roman Catholic priests, Fathers Provencher and Dumoulin, took up their permanent abode in the Settlement, and founded St. Boniface Mission on the Red River, on its east bank, about a mile and a half from Fort Garry. Four years later Provencher was made a Bishop, as auxiliary to the Bishop of Quebec; in 1844 Rupert's Land was detached from Quebec and became an independent See; a quarter of a century afterwards it was erected into an Archbishopric, the Archbishop of St. Boniface having several Bishops under him. These successive changes in the status of St. Boniface sufficiently indicate the growth and development of the Roman Catholic Church in Rupert's Land. The Roman Catholics were almost entirely French half-breeds, a few were of pure French extraction, and the rest were of various nationalities; in 1865 there were between five and six thousand Roman Catholics in the Red River Settlement in seven organised parishes, and they outnumbered, though very slightly, their Protestant neighbours.

The first clergyman of the Church of England, the Rev. John West, came upon the scene in 1820, as Chaplain of the Hudson's Bay Company and, at the same time, as a missionary of the Church Missionary Society. The Company gave him a lot of land, several hundred acres in extent, some two miles from Fort Garry, and on it he built a small church and a small school, which, in the course of years, developed into St. John's Cathedral and St. John's College respectively. Mr. West visited some of the Company's forts in the interior and attempted to evangelise the Indians, but his work was mainly at St. John's, where his congregation was composed of the Company's officers and servants, the English and English half-breed settlers, and the Scottish settlers who belonged to the Selkirk Settlement; the last named were all Presbyterians, and never really became members of the Church of England, though they did not succeed in getting a Presbyterian Minister for themselves until 1851. The district occupied by the Selkirk settlers had now come to be called Kildonan, after the name of the parish in the Scottish Highlands from which most of them had emigrated; the area south of it, including Fort Garry, formed St. John's parish, from the name Mr. West gave to his little church, and is now the main site of Winnipeg.

Mr. West's church was the Mother Church of the Anglican Communion in Rupert's Land, and holds, therefore, a relation to it somewhat similar to that held by Canterbury to England; as time rolled on, the position of St. John's as the Mother Church of all Rupert's Land became more and more accentuated.

Mr. West retired from Red River in 1823, and was succeeded by the Rev. D. Jones, a C.M.S. missionary. On his being appointed Chaplain of the Company, the C.M.S. sent out in 1825 another missionary, the Rev. W. Cochran, who afterwards became Archdeacon of Assiniboia. Mr. Jones founded St. Paul's parish, immediately north of Kildonan, and Mr. Cochran St. Andrew's, north of St. Paul's. By 1831 there were the three parishes--St. John's or "Upper Church," St. Paul's or "Middle Church," and St. Andrew's or "Lower Church," each with a church of its own. Mr. Cochran was a man of decided ability, and quickly became a personage in the Settlement; as has been said of him, he was at one and the same time "minister, clerk, schoolmaster, arbitrator, peacemaker, and agricultural director." To him was due the first real aggressive missionary effort among the Indians; in 1833 he established St. Peter's Mission in an Indian settlement on the Red River, some twenty-five miles north of Fort Garry; he not only Christianised these Indians, but civilised them. After two years and a half of incessant labour he was able to write of "twenty-three little whitewashed cottages shining through the trees, each with its column of smoke curling up to the skies, and each with its stacks of wheat and barley. . . . It is but a speck in the wilderness, and the stranger might despise it, but we who know the difficulties that have attended the work can truly say that God has done great things, were it only that these sheaves of corn have been raised by hands that hitherto had only been exercised in deeds of blood and cruelty to man and beast."

St. Peter's is now a flourishing Indian parish with a large church, four out-chapels, schools, and a parsonage. In 1840 a mission was begun at Cumberland in the interior among the Cree Indians, its minister, the Rev. Henry Budd, himself an Indian, having been trained at the school founded at St. John's by Mr. West. A year afterwards the C.M.S. sent out another missionary, the Rev. Abraham Cowley, who later became Archdeacon of Cumberland; soon after his arrival in the country he established a successful mission among the Saulteaux Indians at Fairford on the shores of Lake Manitoba.

As yet there was no spiritual overseer, no Bishop in Rupert's Land, but the C.M.S. arranged in 1844 that the Settlement should receive a Visitation from Dr. G. J. Mountain, Bishop of Montreal, who, after a journey of 1800 miles, mostly by canoe, arrived in Red River in June of that year. Bishop Mountain found four churches--St. John's, St. Paul's, St. Andrew's, and St. Peter's--attended by 1700 persons, and nine schools with 485 scholars; he confirmed 846 persons, and "communicated" at the Services he held, almost daily, among the settlers. It will be observed that from the beginning the Church of England in Rupert's Land has two aspects: one may be termed colonial, referring to ministrations in settled communities; and the other missionary, concerned with work amongst the Indians; but even in the settled communities the activities of the clergy were largely of a missionary character, and continued to bear that complexion for a considerable period.

Six years before the coming of Bishop Mountain into Red River, Mr. James Leith, an Aberdeenshire gentleman who had been a chief factor or principal officer of the Hudson's Bay Company, bequeathed £12,000 ($60,000) to be expended for missionary purposes in Rupert's Land. The trustees under Mr. Leith's will obtained, after some time had passed, a decree of the Court of Chancery in England, by which the money was invested for the endowment of a Bishopric of Rupert's Land, the Judge who granted the decree being largely influenced by the fact that the Hudson's Bay Company bound themselves for ever to contribute £300 yearly to the Bishop's stipend in the event of such a Bishopric being established. The income from the Leith Bequest and the contribution of the Company together made up an annual income of £700.

The Bishopric was offered to and accepted by the Rev. David Anderson, a Scholar of Exeter College, Oxford, and then Tutor of St. Bee's Theological College, Cumberland. He was consecrated at Canterbury on May 29, 1849; by the royal Letters Patent founding the See, the Archbishop of Canterbury for the time being was declared Metropolitan of Rupert's Land; at that period the Archbishop held a similar relationship to all or most Colonial Bishoprics, and at present the See of Canterbury is still Metropolitan with respect to several Colonial and Missionary Bishoprics. Bishop Anderson reached Red River in October 1849, bringing with him a small band of missionary workers. He had intended to pass the winter in St. Andrew's parish, but on the very day of his arrival the Rev. J. Macallum, who had carried on the school at St. John's for years under the name of the Red River Academy, passed away, and the Bishop at once took up his residence in St. John's, adding to his other duties the care of this school, and teaching in it himself: To this school he subsequently gave the name of St. John's College, desiring it to become a training college for the clergy and a higher school for laymen as well as boys; to popularise it he formed a College Board, but after some years, owing to the difficulty of procuring with the means at his disposal an adequate staff and other difficulties, he was compelled to close the College.

In i8 the S.P.G. sent out its first representative in Rupert's Land to a new parish, that of St. James's, lying immediately west of St. John's along the Assiniboine River, where a small settlement had gradually grown up. A large part of this parish is now included in the city of Winnipeg. Two years later the Bishop visited Hudson's Bay, and at Moose Fort ordained to both the diaconate and the priesthood John Horden, a missionary of the C.M.S., who afterwards became the first Bishop of Moosonee, the Diocese first taken out of the original See of Rupert's Land. In 1853 a mission was established, under Cochran, then Archdeacon, at Portage la Prairie, some sixty miles from Fort Garry, up the Assiniboine, where a church was built and a parish formed. Three other parishes on the Assiniboine came into existence somewhat later--Holy Trinity or Headingley, St. Margaret's or High Bluff; and St. Ann's or Poplar Point; they lay between St. James's and Portage la Prairie.

In 1856 Bishop Anderson visited England, and secured funds for the building of a cathedral at St. John's; the Hudson's Bay Company gave him £500 for this object, and the S.P.C.K. contributed a similar sum. Old St. John's was pulled down and the new building was erected according to plans the Bishop brought from England; the plans had to be reduced, and the structure was not an unqualified success owing to imperfect workmanship; the tower which adorned one end had eventually to be taken down, as, being built on an insufficient foundation, it came in time to lean heavily against the main fabric, which it strained to such an extent that gaping cracks appeared. The edifice was repaired and strengthened, and still serves, though very inadequately, as the Cathedral of the Diocese.

By 1864 Bishop Anderson had more than twenty clergy under him. Missions had been planted in the Far North at Fort Yukon, on the Mackenzie River at Fort Simpson, at York Factory and Albany as well as Moose on the shores of Hudson's Bay, and at various points in the interior--Fort Alexander, Nepowewin, Fort Ellice, Swan Lake, and English River, besides Cumberland and Fairford. The rest of the clergy acted as parish priests in the Red River Settlement. All of them, whether parish priests or missionaries, were supported by the English Church Societies; the C.M.S. maintained no fewer than seventeen, while the S.P.G. found stipends for two, and the C.C.C.S. also paid the stipends of two. The people of the country did little or nothing--practically nothing--for the maintenance of their clergy, but no persistent and systematic effort had been made to get the settlers to contribute towards it.

Bishop Anderson returned finally to England in 1864, resigning the See after an episcopate of fifteen years. His people saw him go with deep regret; he was greatly esteemed and loved for his goodness and amiability; gentle and affectionate, he lived for others. His successor, in one of his first letters from Rupert's Land to the S.P.G., wrote of himself as "sharing Bishop Anderson's doctrinal views, and revering a self-devotion and self-sacrifice amid abounding vexations little known at home in England." After his resignation Dr. Anderson became Vicar of Clifton, and held that important charge till his death twenty years later. He not only continued to take the keenest interest in Rupert's Land, but was one of the ablest and most cordial supporters of all the plans and projects of Bishop Machray for the extension of the Church and the development of the See, his assistance being especially valuable with the Church Societies, and particularly at one or two critical periods, when his enthusiastic endorsement was of decisive importance, as, for instance, in the case of the first division of Rupert's Land in 1872-74. His congregation at his request sent yearly a contribution, which in the aggregate amounted to a large sum, to his old Diocese, and he rendered it good service in a variety of ways. He rejoiced greatly in the growth of the Church and of the country. At the first Provincial Synod of Rupert's Land, which was held at Winnipeg in 1875, a letter from him was read, in which, referring to this Synod, he said: "Too grateful I cannot be to Almighty God for having spared and permitted me to behold in the flesh and hear of so mighty a stride in what was as the wilderness, and which now in so many parts begins to bud and blossom."