|

St. John's Cathedral, Winnipeg; Author of Pickanock, A Novel; Editor of "Leaders of The Canadian Church" (First Series) Eastern Canada; and "Leaders of The Canadian Church" (Second Series) Rupert's Land. THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY LIMITED [1920] |

|

St. John's Cathedral, Winnipeg; Author of Pickanock, A Novel; Editor of "Leaders of The Canadian Church" (First Series) Eastern Canada; and "Leaders of The Canadian Church" (Second Series) Rupert's Land. THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY LIMITED [1920] |

This is the story of John West simply and briefly told. I had to blaze the path for myself and span the chasms, for strange to say no one has thought it worth his while to tramp this way before me. Perhaps if I had known how misleading are the references to this worthy man, and how scanty the information which may be had concerning him, I, too, might have retrained from making the venture, and so have missed some hours of keen pleasure.

One should set himself in such matters to secure historical accuracy first of all: this is a special obligation on those who write of things Christian. A wrong statement once admitted tends to strengthen and perpetuate itself. I have tried hard to avoid this, but there are many little points which could not be cleared up this side of the water, and a trip to England was impossible. I shall welcome therefore any corrections which the publication of this Sketch may elicit.

I have endeavoured to give West his proper setting, to interpret his personality without striving after effect, and to let the reader feel the spell of his inspiration. After all it is in the impelling power of a great example that its chief value is to be found. I trust that West's example may impel us to West's unfinished task--until the night falls upon our own day, making its labours to cease.

W. B. H.

St. Luke's Study,

St. Patrick's Day, 1920.

CHAPTER I.

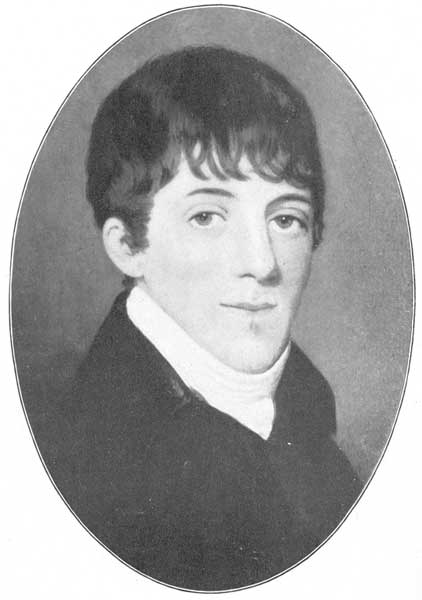

THE CALL.IN the spacious study of Bishop's Court, Winnipeg, there hangs on the wall opposite the Primate's desk the portrait of a young man with a poetic countenance: it is a picture of the Rev. John West, the forerunner of that long line of teachers and preachers who for a hundred years have lived for the spreading of the knowledge of Christ among the races of the great central provinces of Canada.

Mr. West was not a stalwart man, as I should judge--indeed, he lacked every appearance of ruggedness. Nor was he the long-bearded, prophetic-looking missionary so typical of Rupert's Land in after years; on the contrary, he was clean shaven, and wore his heavy brown hair low down upon his forehead and about his ears. His great eyes stood well apart, were light brown in colour, and had plenty of dream and of vision in them. His goodly lips were tightly set, and yet seemed ready for smiling. The chin was broad and protruding, and the jaw unusually long and firm; nevertheless the expression of the face was one of feminine tenderness and spiritual discernment.

It was in Surrey that Mr. West was born, at the little town of Farnham, less than an hour's run from London in these days of fast train service, but a full eight hours' plodding for the horses and stage-coach of a hundred years ago. The place is delightfully located on a hillside to the southward, with the tiny river Wey flowing by down winding lanes of ancient trees and banks rich with many flowers. The country about is pleasant to look upon, having quaint homes, and irregular little fields, with hedgerows and trees of goodly age casting deep shadows. The soil is still rich after generations of tilling, and yields wheat and oats in abundance, and also hops in great wealth and beauty. Hence Farnham has long been a rural centre of importance, holding its weekly market and its autumn fair.

It was in this spot of many natural charms, by the living waters of the Wey, close to the quiet of the open fields, in the peace and beauty of sequestering woods, that John West was born and spent his boyhood days.

But Farnham spoke with other voices than those of nature to the young missionary. At an early date the atmosphere of the place had been colored by the incoming of the Light of Christ, Indeed, if the settlement did not quite owe its origin to the introduction of the Church, its growth to any degree of size and importance was due to the locating there of the Castle of the Bishop of Winchester. It was also the site of the first Cistercian house in England, Waverley Abbey, the ruins of which may still be seen not far away by the little river's edge, and its pretty name furnishes the title of one of Scott's great novels. Farnham in fact was so much a community under Church influence that it was the Bishop who granted the first charter to the town in 1247, and the privilege of holding a fair on All Saints' Day. Besides, the Pilgrims' Way ran past the place, that historic thoroughfare along which countless travellers from their homes in the south and west of England, and many more who had come over from the Continent of Europe, walked or rode to the shrine of the good St. Thomas at Canterbury. Surely it needs but little imagination to picture young West peopling again this highway of the Saints with a motley crowd like Chaucer's Pilgrims; or playing in and about the impressive ruins of the old Abbey, and picturing to himself the while, just what was the character of its life when inhabited by the strangely clad men, who for zeal of Christ and the Church built it as a place of holy thoughts, deeds and prayers in a land as yet remote, wooded and uncultured. The environment of Farnham was, indeed, such as suited well the boy who should go forth himself one day bearing the torch of Faith to other lands. But there were more potent forces at work in the life of young West, and of a more direct and personal nature. Like many a score of others in his day he came under the spell of the Great Discovery. Both the Wesleys were still living when John West was born; Charles lived on for ten years after, and his great brother for two decades and more. Thus the tide of the great Revival was moving at the full when John West's young mind was opening to life's many voices. Of this revival one of the streams, indeed, pressed far inland and came even to Farnham itself. In the secret of this religious awakening lies also the secret of John West's Red River Mission. It is of some interest and of no small importance, therefore, to ascertain as definitely as we can what that secret was. In this quest nothing is easier than to go aside and get lost on some obvious and inviting by-path. It is futile, for example, to seek the explanation of the movement in the fresh emphasis placed on any specific theological doctrine. This has been done with disastrous results. As a matter of fact the leaders were not men of narrow outlook in any way. Their range of theological interest was much wider than is generally assumed. The hymns of the great singers touch nearly every phase of spiritual experience, and their joy in the ever-returning seasons of the Church's Year is fully attested. It is true that their teacher focused in the Cross and turned upon the Atonement, but not so as to screen the Great Personality of the Gospel. For them, Jesus was not confined to history nor enclosed in the sealed casket of the creeds: He was a living and knowable Presence. This was their Gospel. The origin of the New Life was a new Apocalypse of which the Living One, as of old at Patmos, was the content. In the re-discovery of the Living Christ lies the secret of the great Revival and the origin of the Red River Mission.

It is true that Bishop Butler had prepared the way by striking the arm of Deism with its own intellectual weapon, but its "dead hand" still lay on the weakened body of the Church. Its grip had been broken, but it must also be ejected ere the Church could live again. Such a task was too great for reason alone. The whole man must be aroused. The secret by which the Church was to recover herself was at hand. It lay in the rediscovery of the Great Presence who on the field of history appeared once as the Great Personality. The light of the Incarnation broke again before the eye of a new age and cut like a meteor across the night of deistic theories: men found once more a human-hearted God in the life and death of the human-hearted Christ. Thus were the fountains of the great deep broken up. The life of God poured like a torrent into the old channels of the Church, but finding them clogged with unfaith and worldly lusts rose above the banks, flowed over, and made new courses. There were even Prelates among those who scoffed at the new enthusiasm. Ten years before John West was born a company of men were expelled from his college, St. Edmund's Hall, Oxford, for having too much religion. Nevertheless, there were not wanting in all parts of the country both priests and laymen who welcomed the new life but refused to abandon the old Church whose doctrine accorded so well with their new experience, and whose liturgy had fed their souls in the days of dearth. These valiant souls refused to be frowned or scolded out of their Church. We can never be sufficiently grateful for those churchmen through whose souls the new spiritual current found passage, vitalizing in time the whole body of the Faithful. John West was one of those who made the Great Discovery. In consequence he came to our shores to preach the living Christ and found his Church among the neglected traders and the savage redmen wandering over the spacious pasture-lands of the buffalo.

It would be interesting to have minute knowledge of how the attention of the Hudson's Bay Company was directed to Mr. West, as one fitted for its newly-created chaplaincy, but specific information has not come to hand and one forbears to speculate. The important thing is that the choice was well made, for Mr. West was both highly qualified and ready because he had acquired a definite interest in the native races of North America. It is apparent that he had read widely in missionary literature, and was possessed of specific information concerning the aborigines of this continent and the efforts being put forth on their behalf. Indeed, it was because he saw in the chaplaincy a vantage-ground from which to share in the work of ministering Christ to the neglected Indians, that he was driven to his decision. He was a man of forty-five at the time; the age of pure adventure had therefore gone, and the resolve was on that account exceedingly noble and most lucidly Christian. Moreover, he had about him a home of rare attractiveness--a wife of the highest Christian character, possessing also unusual social and literary gifts, and a family of three children passing through the impressionable and fascinating period of infancy and early school days. It meant leaving them for several years, at best, going on a most perilous journey into the northern ocean, and dwelling in a land where savagery was still unchecked; clearly it might be for more than several years. No human experience is more exalted and more mysterious than his at this moment. The love of Christ both intensified and heightened his human affection, and yet demanded the leaving of those on whom it was so freely bestowed. The decision was made, however, and on the twenty-seventh of May, 1820, this "Called Apostle of Rupert's Land," stood on the deck of the brave little sailing ship Eddystone, waving adieu to everything he held dear in this world. I doubt if any soul was ever moved by the love of Christ more purely.

CHAPTER II.

THE COMING.York Factory must have been a dreary enough spot to eyes familiar with the delights of Surrey. And yet the sight of it brought cheers from the lusty-throated sailors of the Eddystone, and stirred in one bosom at least "sentiments of gratitude to God for his protecting Providence through the perils of the ice and of the sea."

There are two rivers breaking through the coast line at this point and pouring their fresh waters into the great salt bay almost as one stream. The land about York is flat, with a great deal of swamp or muskeg, where only low bushes spring, and mosses abound and mosquitoes generate in savage myriads. The only variation in the surface consists of granitic rocks, bare, weather-beaten and sea-worn. The climate is not delightsome even in summer. The days are.seldom clear and warm, usually cold winds are blowing off the bay, and frequently they rise to gales which sweep inland with noise and fury. But uninviting as the region is to the eye and feelings of civilized man, the two converging rivers with their countless tributary streams and sustaining lakes, make it the natural meeting-place of hunters from the inland wilds, and of venturesome traders coming in ships from overseas. Consequently the Great Company built a fort there as early as 1681 and named it York.

At the time of Mr. West's arrival, and for long years before and after, York was the principal centre of the Hudson Bay Company's interests in the vast region under their control.

The buildings of the Fort stood about three sides of a square, while along the fourth ran a picket fence, with a gate in the centre, and a walk leading from it to the main structure of the establishment. Outside the fence there was a narrow strip of land where several guns were placed, and beyond this the river Nelson finishing its long and rapid journey to the sea. In the centre of the quadrangle a tall flag-staff was flying the banner of St. George, and near it stood a bell-tower rising high above the buildings and giving forth at stated intervals those clanging tones which regulated the life of this small white community on the edge of the Indian wild.

Here trading and bartering with all its attendant vices had gone on for nearly one hundred and fifty years, yet there was no calling of the people to the worship of God. Surely this was a crime the stain of which neither Church, nor Company, nor Nation can easily expunge. What wonder if that mid-August Sunday of 1820, when "arrangements were made for the attendance of the Company's servants on Divine worship" was at once a day of humility and of rejoicing. At last the wilderness had begun "to blossom as the rose."

Mr. West's plan, however, of working his vast field included more than the holding of Sunday services for the white adults of the Company's many forts. Two other features come at this time into view, and must be seen in their distinc-tiveness from the outset. One had to do with the children of white men and Indian women; the other with those of purely Indian parentage. The former came within the scope of his duties as chaplain to the Hudson's Bay Company; the latter was a matter of private concern only. On behalf of both these classes Mr. West took immediate action.

As regards the half-breed children he drew up a proposal and submitted it to the Governor of York for his approval. It commended itself to his judgment, and was transmitted at once to the Committee of the Company in London. It advocated a policy of concentration. One hundred of these half-breed children from the scattered forts were to be brought to Red River and there housed and maintained at the Company's expense, and educated under Mr. West's direction. It cannot be said that the authorities of the great trading company had been wholly neglectful of their duty to these unfortunates in days gone by, but not even the least success had come of their well intended efforts. Failure marked them on a variety of accounts. They lacked a well-considered plan for one thing, and often the schoolmaster found it more interesting and more profitable to go fur-trading than to continue in the less fascinating and less remunerative work of teaching school. Moreover the policy of Mr. West involved not only the novel experiment of concentration, but also the equally novel experiment of the boarding school. It also had in it the new element of the specifically religious which fires the imagination and impels by the highest and most enduring of motives. Men might trade for gain in these wild parts, but teaching must needs be rewarded in other coin.

As for the Indian children, matters were somewhat different. They were Mr. West's personal concern to begin with. Any expenditure on them must be supplied from sources other than the funds of the Company. His policy with regard to them, however, was the same, so far as it turned upon their education at a common centre. He looked upon the Indian child as the leader of this wandering race--and his education as the best means of reaching its adult members. There were difficulties in the way, as might be expected. For example, Mr. West had to "establish the principle" that the Indians would be willing to part with their children for this purpose. This issue he put to the test at once and succeeded; for being interviewed on the subject an Indian named Withaweecapo agreed to give over two of his sons to go with the missionary to his destination on the Red River.

Two happy and hopeful weeks, not wanting, however, in lonely moments, thus spent at York brought in the early days of September with its brilliant autumn tints on trees and shrubs, its starry nights, and its mornings of sparkling frost. The long, tedious journey to the Red River had to be resumed, therefore, without delay. So the last letters are written to the dear ones in England: a canoe is selected and canoemen chosen of ripe experience for the missionary; the tents, blankets and provisions are made ready; the morning dawns and clears; the canoemen are at their posts; Mr. West, accompanied by Governor Williams, comes down to the water's edge; With-aweecapo arrives with his eldest boy in his arms and delivers the little fellow to the missionary with a display of much affection; the two wives of Withaweecapo (who are sisters) stand on the bank weeping and gazing through their tears in fond hope as the little chap and the servant of Christ step into the canoe; a stroke or two of skilful paddles, a final waving of au revoir, and the frail craft is pressing its bow against the stream; they are off. The redemption of the noble redman has begun.

The distance to be covered was quite eight hundred miles; up swift streams for the most part, with rapids and falls in distressing number, and over lakes of limpid water till count and memory of them are lost. The route lay past Norway House, an inland post of considerable importance belonging to the Company. Here Mr. West secured another lad to go with him and little Withaweecapo to the Red River.

From this point onward the character of the journey was very different. The region of rivers and small lakes was passed, and a most perilous voyage lay ahead. The remaining three hundred miles was one vast lake, and after it but a short stretch of slow-moving river. Nor is Winnipeg a peaceful lake, for it abounds in shallows, and the winds easily lift the waves mountains high. Mr. West's canoe was therefore abandoned at Norway House, and with his fellow travellers in the Company's affairs he and his boys took to York boats. Not large craft these, by any means, but capable of carrying a considerable load; and while usually propelled by rowing, yet in moderate weather, and with skilled management, may be driven forward without danger, under press of sail. Once when the distance was half covered Mr. West's boat carried him well nigh to misfortune. In a lively breeze it struck with shocking impact upon a sunken rock. For a moment it seemed that all was lost, but prompt action and a kind Providence put things right again, and sent Mr. West once more to blessing God for His mercy.

At sunset of every day the boats were drawn up and the night spent on the rugged, woody shores, where tents were pitched, and fires lighted to cook the evening meal and to ward off the damp and the falling frost. One evening as Mr. West sat in his tent door before a little fire, an Indian came forward and spoke to him a word or. two in English, explaining that he knew of Jesus Christ, and desired to learn more of Him. This simple incident provides a picture which stirs the imagination and which suggests all the essentials of this man's great undertaking. It reveals the soul of John West, mirrored in whose depths, as in a lucid spring, we behold the living Christ and the neglected Indian: to bring them together--to let them speak and know each other--Surrey and his family were far away and he alone on the shores of this wild inland sea.

When a week of this travelling was nearly over the south shore of Lake Winnipeg came in view at dawn--a long, low, curving line on the waters against the brightening sky. Presently the sun rose "in majestic splendour over the lake," and the boats entered the mouth of the Red River. About them were far-extending marshes wearing the deep green and russet brown of autumn. Flocks of wild fowl rose with whirring wings into the morning light and made off through the cool air to quiet spots among the long marsh grasses.

A little way up the slow, muddy stream (such a contrast to the clear waters of the lake and of the swift-running Nelson) the rowers pulled their boats ashore and breakfasted at Netley Creek. [Since known as the Indian Settlement, now St. Peter's.] Here was an Indian encampment--and the headquarters of an Indian chieftain named Pegowis, who also breakfasted with them. Years after, when Mr. West had gone away from the Red River, Pegowis found the significance of his coming that morning--and he led his tribe out of darkness into the Light of Christ. Meantime, with that native courtesy which is characteristic of the true Indian, he spoke these beautiful words of welcome to the missionary: "I wish that more of the stumps and brushwood were cleared away for your feet on coming to see my country."

After the early morning meal, the canoe was soon on its way again pressing its bow steadily up the soft flowing waters of the Red River. The following night was spent somewhere on the route possibly just after passing the Grand Rapids. [Now St. Andrew's.] The next morning began the last stage of the long voyage. It was a pleasant paddle, for the missionary felt his spirits rise as he neared his destination and his work. The wide and dangerous lake was now passed, and the river with its near-by shores had the look of friendliness. Further, its windings and wooded points and heightening banks lent an air of mystery which kept the traveller ever on the alert for some new disclosure of interest; now the banks were high and the voyagers felt themselves dropped into a canal of running water; next the rapids dashing over a ledge of limestone and rushing into the narrow channel below, broke the stillness; here was a cluster of ragged teepees--there a little whitewashed log cottage, and yonder a lime-kiln all but lost to sight in the muddy bank. For the most part the shores were forested with oak, elm, ash and poplar, and even a specie of maple. Some trees were already in the nakedness of autumn, others had lingering yellow leaves, flashing in the sun and reflecting themselves in the quiet of the river. At times a break came among the trees and the eye wandered on grey plains illimitable. So voyaging to the land of his vision and his high hopes, Mr. West's canoe turned one last bend in the river about fifty miles from where he entered it, and there on the right he beheld high upon the muddy bankthewoodenpalisade of Fort Douglas. Watch a moment this arrival and disembarking! You see stepping ashore the first ordained preacher of the unfettered Gospel beyond the Red River; and there are the boys who have come with him from York and Norway, the first of the Indian children to pray, "Great Father, bless me, through Jesus Christ," and destined to become heralds of the Faith to their fellow dwellers in the long night of paganism and wretchedness.

Gaze long and earnestly on this little company following the grey pathway up the corroded bank of the Red River into the slanting sunbeams and disappearing through the palisade into Fort Douglas, for no event of equal significance is recorded in the early life-history of our Great North-West.

CHAPTER III.

THE FIELD AND THE WORK.Fort Douglas consisted of a little group of wooden buildings with a palisade of pointed oak logs standing round about them. The river is wider here than usual and bends abruptly. The Fort stood in the angle of the bend affording an extended view both up and down the stream. Moreover the western bank on which it was situated is of considerable elevation, thus giving a clear range of vision across the water, over the low bank beyond, and away to the eastward. In a westerly direction there was nothing at the moment, but an Autumn grass plain and the going down of the sun. Fort Douglas was not by any means one of the oldest posts of the Company, nor was it classed among the most important for trade; nevertheless it was the heart of what life there was in the region of the Red River when John West came. It was the residence of the Chargé d'Affaires, and the place where stores were kept and furs traded for them. The mail boats came thither from Montreal bearing the slow travelling news of the world then so remote; the fur canoes paddled to it from Brandon House and Qu'Appelle on the rapidly flowing Assini-boine, drew up, unloaded and loaded again by its water's edge.

In days not long prior to Mr. West's arrival Fort Douglas was an object of desire on the part of envious rivals in the fur trade, and the scene also of daring escapade and of tragedy. From it one day a few men went out, proceeded along the west bank of the Red River three quarters of a mile, till they stood beneath the palisade of Fort Gibraltar, at the junction of the two rivers; when they returned they had drawn the sting of their deadly rival, the North-West Company bringing back the enemy's guns in triumph to Fort Douglas. One day in June, 1815, Governor Semple was looking out of the watch tower and saw the Metis coming. He went forth with a few men to meet them, and to meet his death as well. After this unhappy event Fort Douglas passed for a time into the hands of the ill-advised champions of the North-West Company. It happened also that one night not long after this that daring men were making scaling ladders in the woods by the Assiniboine near St. James'. In a blinding snowstorm and in the dead of night they carried them to Fort Douglas, scaled its walls and took and kept the prize for its rightful owners.

Around this interesting centre there were scattered dwellings of rough structure; huts, Mr. West designates them, with his old-world memories still fresh. "In vain did I look," he remarks, with an air of depression, "for a cluster of cottages, where the hum of a small population at least might be heard as in a village." And along the margin of the river, both down and up and beyond it as well, he who walked abroad that October evening beheld the same unattractive and uninviting houses where men and their families dwelt. At the meeting of the rivers (to the north of the Assiniboine) stood the fort of the North-West Company. Across the Red River was to be seen the outline of an unfinished Roman Church, with a small house adjoining for the priest. For the most part, however, there was only the piteous teepee of the Indian and the open sweep of the prairie.

There was a considerable variety of races among the sparse population, and many degrees of difference in intelligence and in the still higher things of the ethical and spiritual life.

First may be mentioned the active officers of the Hudson's Bay Company, often men of great ability and not wholly ignorant of the social customs of the Old Land. And then the Red River was the favorite resort for the retired servants of the great Company. It was a matter of considerable pride to have been identified with its interests, and in the evening of men's lives something of its prestige still clung to them.

Next in importance were Lord Selkirk's Highland men, recent comers, making trial of the soil and the climate for the support of a settled population. They excelled in determination, and their patient endurance was heroic.

The only other elements of importance in the white population were some French-Canadians, descendants of the venturesome sons of the old province of Quebec, who from the days of La Verendrye explored the forest and the treeless plains of the west, and have left enduring memories in names which still adhere to many places.

Another class which Mr. West notes was German in origin. Its locality lay just beyond the Red River, where a little muddy stream furrows its way through the rich clay soil. The De Meuron soldiers whom Lord Selkirk had brought with him from Eastern Canada in the troublesome days of 1817 were given land along its banks when their services were no longer required. They were placed thus near Fort Douglas, which they had captured from the North-West Company, that they might still keep watch over its interests and protect it in case of need.

At a later date came in some Swiss immigrants, artisans for the most part who helped to give variety and romance to the colony during their short residence in the place.

The community was, therefore, quite cosmopolitan a hundred years ago, as it is to-day. And here in the valley of the Red River, each coming in through its own gateway, we see in particular the meeting of the two races, which from the earliest days have given colour to the history of Canada and have contended for the mastery of her destiny. Here also the two historic churches meet again to vie with each other for the possession of the field, and yet we trust to serve in common the larger issue of Christ and the people's weal.

Social conditions at the time of Mr. West's coming were in many ways as bad as they could be throughout the territory of the great trading Company. It is not to be wondered at, that such was the case.

The background is dark--it is the savage life, not without its nobler elements indeed, but lacking the power if not the will to give freedom and control. The cruel man, the suffering woman, the neglected child, was everywhere. The Indians did not cultivate the soil, though it was exceedingly rich and vast in extent. Consequently they had neither settled abode nor substantial dwellings, nor regular and abundant supply of food. Hunting was the only source of physical existence, hence they must needs wander, suffer cold, go hungry, and even starve to death. Warfare on the slightest provocation aggravated the suffering of the weaker ones among them as much as it delighted the young fighting men. Vengeance was the reigning law and scalping the typical treatment meted out to captured enemies.

Until the arrival of Mr. West the Indians were untouched by the finer elements of our civilization. It is difficult to write with restraint of this long neglect and its consequences in multiplying the sorrows of the women and children of this race. Heretofore civilization not only withheld the touch of its soothing hand and the dynamic of its redemptive force, but it scarred the body afresh and poured in vials of moral disease. The rum-keg was the currency of the region, for which the Indians parted with the meagre results of their chase and with their young women as well. It is shocking to think that the gentlemen adventurers of the Hudson's Bay and their families in the old land, members of the Christian Church no doubt, could live for many decades in full enjoyment of the profits of trade with the natives roving on the bleak shores of our arctic seas and the Christless plains of the Canadian West, and yet give no heed to the Indian's cry for the Bread of Life. It is no wonder Mr. West burned in his indignation and cried out, "My soul is with the Indians."

Marriage was ignored on the part of many of the white employees of the Hudson's Bay Company; in fact it was impossible. Hence it is not to be wondered at that European men lived freely with Indian women. "When a female is taken by them, she is obtained from the lodge as an inmate of the Fort, for the prime of her days generally." The woman was frequently deserted when years were creeping on, or when her white husband moved to another scene of occupation. No course was then open to her but to form if possible another temporary alliance or return to her tribe, while her half-breed children were left in utmost neglect of body, mind, and soul.

It is also significant that "there was no criminal jurisdiction established within the territories of the Hudson's Bay Company." An offender had not much to fear; if evidence against him was beyond question, he might be sent to Montreal or London for trial--a poor deterrent against crime. The result was many serious offences every year, and "Europeans falling to savage levels and even lower."

Nor was there any adequate military protection. The scattered community on the Red River was left pretty much to its own resources. The Company's fort made a show of defence with its stockade, its lookout, and a few old guns. Nevertheless there was constant danger of Indian raids, and more than once we find Mr. West prominent among those who are consulting together on the stirring question of how best to meet probable attack.

Such were the circumstances of human life on the Red River, when the transforming truth of the Gospel was introduced.

The centre of Mr. West's operations was Fort Douglas. The long voyage from England had come to an end here on Saturday afternoon, October 14th. The following day in one of the rooms of the Fort the "servants of the Company were assembled for Divine worship." This was the beginning of those regular Christian services, which, thank God, have ever since risen in prayer and praise from the people of this land. It is not to be wondered at that tears flowed down the cheeks of strong men on hearing in this wilderness the once familiar services of the Church of their mother land. This rectangular Fort on the river bank, set about with its palisade of pointed oak logs, was the only Church west of the Red River for many months, and the spot on which it stood should ever be dear to the hearts of Churchmen.

There were other interests, however, requiring prompt attention. Mr. West had brought with him a schoolmaster, Mr. George Harbidge, who had been educated at Christ's Hospital and apprenticed to Bridewell. Like Mr. West he was an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company. A log house, some distance down the river, was at once secured and the work of repairing and altering it put under way to make it suit the requirements of the school and serve as temporary abode for the teacher. In a short time it was ready. Within two or three weeks at the most, after his arrival, Mr. Harbidge "began teaching from twenty to thirty children." In this simple way another fundamental work was started by the Christian Church for redeeming the life of the people. Mr. West's own residence was removed, after two months or so, from Fort Douglas to "the farm, belonging to the late Earl of Selkirk," some three miles distant. This he made his dwelling place, and to it he ever returned from his long trips during the years of his sojourn in the land.

But however comfortable and otherwise satisfactory each of these centres might be in itself, the plan as a whole lacked unity. Mr. West was not slow to appreciate this inherent disadvantage and set himself resolutely "to erect in a central situation a substantial building, which should contain apartments for the schoolmaster, afford accommodation for Indian children, be a day school for the children of the Settlers, enable us to establish a Sunday school for the half-caste population--and fully answer the purpose of a church for the present." The spot selected was a mile or more north of Fort Douglas on the bank of the Red River, where a small stream flowed into it from the westward, under heavy elm trees and twisted willows. [St. John's Cathedral is near, not on, the spot; and the brook is filled up save for a bit of gully where it entered the river. A rustic bridge spans the gully, and the trees still grow strong thereabout.]

But if the centre of Mr. West's work was Fort Douglas his field of operation was wide--as vast indeed as the land itself over which the Company's trading posts were scattered. On his incoming journey he had spent some time at York and called at Norway House. After three months on the Red River the time had come to cross the winter prairie to Brandon House and Qu'Appelle on the Assiniboine, to the westward. His record of this trip is rich in picturesque detail of the country as it then was. He travelled in a cariole drawn by three wolf dogs, slept well under the open sky and the cold stars, had his nose bitten by the north wind, saw herds of buffalo, just escaped bands of savage Indians, witnessed the "staging of a corpse" at Brandon House, and looked with horror on bacchanalian revelries of drunken savages at Beaver Creek. At both the posts he called the Company's servants to divine worship, instructed them diligently during his stay, and before leaving brought order and sanctity into their social life by the ministering of the sacred rites of baptism and marriage.

Another journey of his taken in the early spring time of that year is likewise marked by some informing incidents. His destination was Pembina, where was Fort Daer, famous as the place of refuge for the Selkirk colonists on more than one of their evil days. The purpose of his going thither was to attend a meeting of the principal inhabitants of the Red River region called to discuss ways and means of defending the Settlement in case of attack by the Sioux Indians. During the previous summer they had scalped a boy not far from the Settlement, and left a painted stick upon the mangled body, which was taken to indicate their determination to return. During his stay at Fort Daer he "went out with some hunters on the plains and saw them kill the buffalo," riding his own horse full speed into the midst of a herd of forty or fifty, then on their spring migration to the south. On the Sunday which fell within his visit he preached at the Fort, and while he was listened to with attention he became depressed in spirit over the spectacle of "human depravity and barbarism" which he was called to witness. In all this the man is revealed no less clearly than the country in which he chose to dwell for the love of Christ and wretched human beings.

When the spring time of his first year had fully come, we see his resolve to have suitable quarters forcing itself to realization. "I have twelve men," he writes, "employed in building the school-house." And we can appreciate his joy in these visible tokens of his work when in the approaching autumn of that year he writes thus: "I often view the building with lively interest as a landmark of Christianity, in a vast wilderness of heathenism." The work went on slowly, however, owing no doubt in part to Mr. West's absence during the summer at York Factory. On the voyage he had the good fortune to fall in with Mr. Nicholas Garry, a director of the Hudson's Bay Company, and a gentleman of fine character. It was the year of the great Amalgamation, and Mr. Garry was travelling through the region for the purpose of clearing up the details of this exceedingly important agreement.

The chaplain and the director met at Norway House, a post of the Company on the Nelson River, where it widens into the beautiful waters of Play-green Lake. They continued their voyage together down the river, and much came of the intercourse which the trip afforded. Mr. Garry became fired with Mr. West's enthusiasm for the mission at Red River and for his plans concerning it. At York they formed a branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society, the first in North-West America. And in consequence many copies of the Scripture in various languages were sent to the Company's posts and circulated among the people around them. Moreover, when they parted, Mr. West for the canoe, the rough fare and the tedious upstream journey to Red River, and Mr. Garry for the sailing ship, and the great ocean and the homeland, a new and fuller life had been resolved upon for the redemption of the races of the long neglected trading lands.

When Mr. West returned from York he found the mission building far from ready, and the winter near at hand to put an end to further effort. In the spring of the following year work was resumed, but in the meantime new quarters were secured for the schoolmaster and the Indian boys. Fort Garry was then nearly finished. It came into existence as a result of the amalgamation of the two great trading companies, and was intended to fill the place of both the original posts of Fort Douglas and Fort Gibraltar. At this time a room was also secured in the new fort to serve as a church until Mr. West's building project should have come to maturity.

The new structure by the river and the brook went on steadily rising throughout the summer and was joyously opened for Divine worship in the early autumn. In the beginning of October, 1822, Mr. West was able to write, "There are six boys, two girls, and a half-breed woman (named Agathus) to take care of the children upon the establishment."

The chaplaincy at the Red River had thus got nicely under way. But when it had run well nigh eighteen months of its course purely as an undertaking of the Hudson's Bay Company on behalf of its own employees, a notable change took place. It passed under the direction of the Church Missionary Society and enlarged its outlook so as to include the native races and make their evangelization a matter of no secondary concern.

The new arrangement was quickly effected in the end, but forces had been at work long previous to the actual transfer of management. Of these Mr. West himself was chief. He was an active member of the Society at the time of his appointment to the chaplaincy. He it was who first drew the attention of the Church Missionary Society to the Indian races wandering on the plains of British America, east of the Rocky Mountains. This he did just prior to his leaving for the Red River in 1820. The Committee was impressed at the time with the strength and character of Mr. West's appeal, but its commitments were already great and its eyes turned towards Africa and the East; it could not therefore embark upon such a mission for the moment. Nevertheless the door was not barred and bolted. Mr. West's "very judicious paper" was kept for reference, and the sum of one hundred pounds granted to enable him to make trial of what could be done for the natives who lay outside his immediate sphere of duty as chaplain. Having reached York and the Red River and seen the Indians in their wretchedness, his appeals to the Society spoke with fresh authority and burned with intense fervency--they were irresistible. But he brought other forces to bear on the situation as well. Influential men whom he chanced to meet at Red River or about the Bay caught his own inspiration. Chief of these was Mr. Nicholas Garry. Mr. Benjamin Harrison also, who, like Mr. Garry was a director of the Hudson's Bay Company, became fired with John West's zeal for the poor Indians. The outcome of Mr. West's zealous communications to the Society and the visits of his emissaries was a special meeting of the Committee probably in the autumn of 1821, at which the Church Missionary Society enthusiastically committed itself to the mighty work of evangelizing the hitherto neglected Indian races of North-West Canada. Mr. West, by the grace of God, had won a signal triumph. Who can tell of all it has meant for poor humanity!

The leading features of the new arrangement are important in detail as in principle. According to it Mr. West would continue chaplain to the Hudson's Bay Company as in the past, but in addition would act for the Church Missionary Society as Superintendent of the Missionary Establishment. Another clergyman was to be sent out at the expense of the Society to work under Mr. West's direction but within the Society's special field of operation. Mr. George Harbidge, the schoolmaster, now became an employee of the Society and was placed in charge of the school. The buildings were to be enlarged and the number of Indian children limited for the present to fifteen boys and an equal number of girls. Other children were to be taken at the expense of their parents or guardians.

This change became effective on October 1st, 1822, and in the spring of the next year, when Mr. West was leaving the Red River, it was an institution of no small importance in itself, considering the community; and moreover it was destined to become the germinating plot of much that is best in the subsequent life of Western Canada. It was the residence of the schoolmaster Mr. Harbidge, now happily married, and assisted by his young wife, in the work of teaching. It was the home of the Indian boys and girls under the motherly care of Agathus. It was likewise the day school for the children of the Hudson's Bay Company's officers and servants, and for those of the Settlers also. On Sunday mornings the congregation numbered at times one hundred and thirty, and' in the afternoon boys and girls and adults as well assembled there for instruction in the precious truths of Christ. The Depository of the Auxiliary Bible Society, founded at York Factory by Mr. West and Nicholas Garry in 1821, was now lodged in the Church Mission House, and from it the Word of God was freely distributed in twelve languages.

Nor have we yet exhausted the activities of this little Mission Station on the banks of the Red River. It had its agricultural interests with plots of ground for the native children, in which they greatly delighted. It had also a farm with Mr. Samuel West in charge for the supplying of the inmates with the fruits of the earth; and even an Esau resided there, a mighty hunter, to kill and bring home the products of the chase for hungry little natives and their white teachers. In a tower recently added to this building of many functions, a bell rang out to call the dwellers in the land to Divine worship.

Mr. West records his feelings of delight at the situation in the following words, written shortly before his leaving the Red River: "As I was returning from visiting some of the settlers about nine or ten miles below, one evening, the lengthened shadows of the setting sun cast upon the buildings, and the consideration that there was now a landmark of Christianity in this wild waste, and an asylum opened for the instruction and maintenance of Indian children, raised the most agreeable sensations in my mind, and led me into a train of thought which awakened a hope, that, in the Divine compassion of the Saviour, it might be the means of raising a spiritual temple in this wilderness to the honour of His name. In the present state of the people, I consider it no small point gained to have formed a religious establishment. The outward walls, even, and the spire of the church, cannot fail of having some effect on the minds of a wandering people, and of the population of the Settlement."

The closing scene of Mr. West's life at Red River, and his leave taking, after well nigh three years, is best told in his own touching words: "On the 10th of June I addressed a congregation, in a farewell discourse, from the pulpit previous to my leaving the colony for the Factory; and having administered the Sacrament to those who joined cordially with me in prayer, that the missionary who was on his way to officiate in my absence, might be tenfold, yea, a hundred-fold, more blessed in his ministry than I had been, I parted with those upon the church mission establishment with tears. It had been a long and anxious and arduous scene of labour to me, and my hope was, as about to embark for England, that I might return to the Settlement, and be the means of effecting a better order of things.

"The weather-was favourable on the morning of our departure; and stepping into the boat the current soon bore us down the river towards Lake Winnipeg. As the spire of the church receded from my view, and we passed several of the houses of the settlers, they hailed me with cordial wishes for a safe voyage, and expressed a hope of better times for the colony. Then it was that my heart renewed its supplications to that God,--'who is ever present, ever felt, In the void waste, as in the city full,' for the welfare of the Settlement, as affording a resting place for numbers, after the toils of the wilderness in the Company's service, where they might dwell, through the Divine blessing in the broad day-light of Christianity." Having reached York, Mr. West stretched out his hands in the name of his compassionate Master to another race, the unshepherded Esquimaux of the West coast of Hudson's Bay. His concern for this people had been aroused on meeting some of them during his incoming voyage through the Straits. But a great name is forever associated with Mr. West's own in this undertaking to carry the Gospel to these stern defiers of the icy North--that of Sir John Franklin. On a previous visit to York the two had met. A hero each, in his own sphere, their souls were akin, nor were they diverse in their love for humanity, nor in their belief that it is ever the highest kindness to give men the redeeming vision. The time had come for Mr. West to take the journey, and Captain Franklin was ready with advice concerning the way, even as at an earlier date he gladly went as his friend's deputy to plead the cause of the Esquimaux before the Society in London. Space forbids my relating the stirring incidents of this tramp overland from York to Churchill. It must suffice to say that the distance alone was not of least account. There was no open trail over this two hundred miles of sea coast. Moreover the ground was swampy, brushwood entangled the feet, water lay ankle and often knee deep, and mosquitoes in their myriads set upon the traveller by night and day and drove even the beasts of the forest to seek refuge in the sea waters. After several days provisions failed entirely, and there was left them only the chance dinners afforded by unwary creatures of the woods. At length his goal was reached. The spirit of Mr. West never burns more brightly than at this time, nor are the qualities of his character ever seen in finer colors. On the eve of his sailing for home, he might have shrunk from so hazardous a journey. Were not wife and children whom he had not seen for three years awaiting him with heavy yet hopeful hearts! Why endanger to so great a degree the fulfilment of their longing and his own! Or had he wanted excuse, he might well have pleaded the endurances and achievements of his years at the Red River and there about. Not so John West! For there was in him a noble abandonment to Christ, hence the call of the Esquimaux went to his soul like the cry of a lost child. And we see again that self-surrender and that self-sacrifice which imply strength of confidence in the Living One. Consequently there is not a trace of murmuring or delay, but on the contrary a prompt setting forth, a resolute endurance of stern conditions, and even a joyful gratitude to God for the privilege of visiting the wild inhabitants of the rocks, with the simple design of extending the Redeemer's Kingdom among them.

The servants and officers of the Company were assembled for Divine worship; the Esquimaux "surrounded him in groups"; he spoke to them through an interpreter, Augustus, formerly of Franklin's expedition into the far North, and they gave him in response an appeal which must never grow faint in the ears of churchmen--"We want to know the Grand God."

But another result blessed this journey of Christ's servant--two little boys were entrusted to him for his establishment at the Red River. With these as first fruits of a race brought out of darkness by that true saint of the Northland, Dr. Peck, and others, he set out on his return to York, covering the distance in seven days. On his arrival, to his unmixed delight he found that God had sent forth his expected assistant in the person of the Rev. David Jones. To his keeping he gave over the two Indian boys, and after a few days' prayerful conference on the affairs of the Mission, the men of God parted and Mr. West sailed away from a land in which his name will always be held in grateful memory by those who have eyes to see that the forces which came in with him and with such as he are those which redeem and glorify life, and guarantee the progress, the kindness and the permanence of civilization.

It is difficult to form a just estimate of a fellow man, and still more to set him forth in cold words, for personality is so shy, so elusive, so much a thing of life and therefore of mystery. Through acts (and thoughts are acts for our purpose, yea and feelings and aspirations as well) the real man, the distinctive thing in him, presses its way to recognition and lives in what endures of his earthly task. What John West was, therefore, we may see in what he undertook that other men left untouched. I have no desire to make him out a great man, and it is not needful to add that he was no common man: the little story now told is witness enough of this. Men's lives are made perhaps not more by the qualities born with them than by the forces which surround them after birth. West was fortunate in both, yet more fortunate still in this: he chose well the powers which should come in, have place and rule. First of these was He whose life shows Him to have been first of men, and of whom experience proves His claim to be the Living Lord.

It was Mr. West's fixed purpose to return shortly to Red River and to bring his family with him, but in the providence of God his life was not so ordered. On the contrary he was induced by the New England Company to go on a tour of inspection to the Indian Settlements in the Maritime Provinces and Upper Canada. But this is another story, and a very worthy one, to be told some day, and found, let us hope, another thread of gold binding Canada East and West together in the firm resolve to see full justice done by a great young country to a highly gifted and noble race, from whom it has inherited a land so rich and vast.

This mission ended, Mr. West returned and spent his remaining years in his native land, becoming rector of the parish about which his childhood memories clustered. The important living of Farnham was conferred upon him by the Lord Chancellor in 1834, and on the same "occasion he was appointed chaplain to the Earl of Bess-borough, then Viscount Duncannon."

The appeal of the "wanderer," however, continued strong upon him, and to his normal duties of parish priest he added during "the latter years of his life the work of promoting the establishment of a school for the education of the children of Gipsies." The site chosen was midway between the two churches of Chettle and Farnham. The corner-stone was laid by a converted gypsy of great age. Mr. West, however, was not to see the completion of the structure from which he had hoped to witness so much good flowing out to the objects of his compassion. The work was still in progress when he came suddenly to an end of his earthly career during the happy Christmas season of 1845.

The pretty little church of Chettle is only a mile from Farnham, and was a portion of his parish. Here John West lies buried, and a window stands in the chancel to his memory. His enduring memorial, however, is of another kind and in another land--even the growing temple of the living God--in the mighty provinces of Western Canada.

Project Canterbury