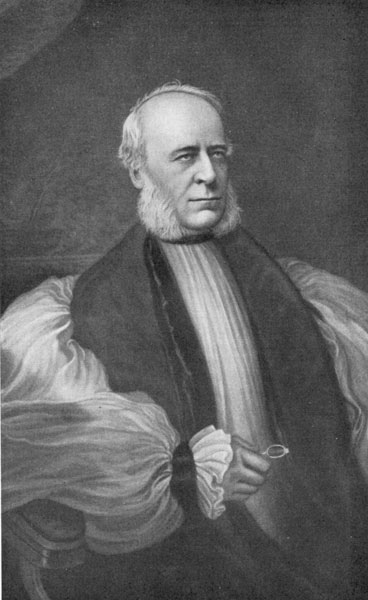

JAMES MOORHOUSE, the second Bishop of Melbourne, was consecrated on October 22nd, 1876, and arrived in Melbourne on January 7th, 1877. His reputation had preceded him, and he found a special train waiting for him at Williamstown, and upon arrival at Spencer Street station, the Governor's carriage was in readiness to take him and Mrs. Moorhouse to Government House as the guests of Sir George and Lady Bowen. Moorhouse, "the Sheffield Blade," was born at Sheffield, the son of a cutlery merchant. After some business experience he had graduated at St. John's College, Cambridge, as Senior Optime in Mathematics in 1853. For four years he was curate of St. Neots in the Diocese of Ely, and immediately showed originality by the formation of a People's Institute, which was a club for working-men, and the fore-runner of a large University College. He had learnt the value of intellectual brotherhood with the working man, and convinced that they were by nature religious, it was to them that he first devoted himself. He attacked indifference, scepticism, with its plausible attacks on Christianity, but above all, gross materialism. In his zeal for souls, he preached from waggons at Sheffield Fair. At Hornsey, to which he was appointed in 1859, he developed his powers as a ready speaker and an eloquent debater, and when he was transferred to St. John's, Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, in 1862, his powers as a preacher were so recognized that Cambridge University elected him as Hulsean Lecturer. He had previously rejected the offer of a Fellowship at St. John's, Cambridge, preferring to enter into matrimony which the Fellowship then debarred. By the time he reached St. James', Paddington, London, as Vicar in 1870, his learning and intellectual power had made his influence wide. In 1874 he became Warburton Lecturer at Lincoln's Inn, and in the same year he was appointed Prebendary of Caddington Major in St. Paul's Cathedral, London, and Chaplain in Ordinary to the Queen.

[44] When Moorhouse was offered the Bishopric of Melbourne, many of his friends (including the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Tait) pressed him to remain in England, feeling that before long he would be offered an English Bishopric. But Moorhouse saw that there were great opportunities for work in the colonies, and even though only a few days later Lord Salisbury offered him the Bishopric of Calcutta and Metropolitan of all India and pressed it, he felt it unfair to withdraw his original acceptance of Melbourne.

Victoria offered Bishop Moorhouse a great, though difficult, field of work. Unbelief had become unusually widespread in the young democracy, and the onrush of liberalism and secular education had resulted in a general feeling that Christianity was for the intellectual and educated man, an outworn creed. Secularism had gained in fact such power in politics, that religion, even in its most elementary form, was banished from the schools. James Moorhouse had proved himself a fighter from the time of his undergraduate boxing days, and here the adversaries of religion had to deal with one whose knowledge of the subject exceeded theirs, and one who was more eloquent as a speaker and not less ready in debate. In his ten years episcopate, this brilliant prelate became an intellectual leader in the land, one of its strongest spirits and its most vigorous personalities. (54). "The character of his work was most gratefully recognized throughout the whole colony," said the Argus of 1886 (55), and the entire press of the colony bore testimony to the good and enduring work of the Bishop during his colonial career. Its columns afford abundant evidence that, on occasion, Moorhouse could defend the Faith, and the Church of which he was a Bishop, with the force and skill that made the enemies of either hesitate to enter on a second encounter. A thinker of the school of F. D. Maurice and Charles Kingsley whose names are closely linked with Christian Socialism and the co-operative movement born out of the troublous times of the Chartist agitation (1848), Moorhouse captured popular imagination by the force and daring of his utterances, and his hold on the people of Victoria never relaxed. As a public speaker he had no serious rival in Australia at that time.

[45] Bishop Moorhouse was installed at St. James' Cathedral on January 11th, 1877, and accepted the constitution of the United Church of England and Ireland in the Colony of Victoria. He immediately set himself to grapple with the ecclesiastical problem of the "Church of England in its relation to colonial society, colonial wants and colonial thoughts." (56). He said that he had heard that "in Victoria, not only ministers of religion but bearers of office generally, did not meet with much show of outward respect, and, that he must expect that every man would think himself as good as him (the Bishop) and a great deal better!" But he was used to that for "he had been born in a democratic community, brought up in it and ministered to it, in England." (57).

He quickly saw, that whereas the population of Victoria was 830,000, those who attended no place of worship numbered 570,000 or two-thirds of the whole. . . ". . . he cared nothing about its rich lands or its commercial enterprise . . . until the people of this country became a righteous people there was no hope for the country. By and by, all good things turned to curses, if the man who received the blessing was not a righteous man." (58).

Moorhouse had heard that poverty had been limiting the work of the Church of England in Victoria, but "he looked around and could not see it; he wanted a little of the money that people devoted to their fine houses." (59). He maintained that the Church of England did not rely upon brilliant preachers or revival services, for the "work of the clergy was intended to be patient working, a long continued application of a force which was one to be measured not only by its intensity at certain points, but by its mass in the whole they prevailed by feeling that they were all members of one great church, working hand in hand above all parochial selfishness to the attainment of one great end." (60). He saw there were two wants existing, a higher culture for the clergy, and the means of giving central and united expression to the teaching, work and worship of the Church. The former of these was necessitated by the culture of the age, and the second by the centrifugal tendency of ecclesiastical thought and feeling. These wants were to be supplied by Trinity College and the erection of the Cathedral.

[46] Within a few weeks of his arrival, Moorhouse had formed an influential committee to promote the erection of a Cathedral, but he felt that the greater need was the want of a cultured, earnest and native ministry, independent of English resources, for whereas "superstition was a formidable enemy, universal scepticism was a more formidable one." He took steps to found a Theological Hall at Trinity College, and founded the first Theological Studentship with a sum of £1,000, given him as a parting gift from his parishioners at St. James', Paddington. Today, there are over 14 such studentships, and over 150 clergymen have passed through Trinity, including more than seven future bishops. Moorhouse also advocated the admission of women to the University, and in 1853 Trinity became the first college in Australia to throw open to women the benefit of college tuition, and Janet Clarke Hall, formerly called Trinity College Women's Hostel, was established in 1886.

Moorhouse welcomed broadening of thought and looked through unity of thought to a faith "so broad and catholic that by the side of it, petty differences that distinguished sect from sect should be seen to be insignificant." "My dimensions," he said on one occasion, "are the height and breadth of the Church of England." There was, however, nothing vague in his religion, for he felt that his Church had two or three qualifications for the broadening of thought which would effect real union of the churches. First, there was that "faithful evangelical witness, or the determination to know nothing in all their forms of doctrine, save Jesus Christ"; and secondly, there was "the wise reticence on some subjects by the fathers of the Church, such as not defining the nature of inspiration"; and finally, because of "her wise and patient historical spirit through her connexion with the apostles in a long historic claim, she was in the habit of looking at all questions from the point of view of their historical interpretation." Moorhouse looked to clergy trained in that faithful and historical spirit of the Church of England, for he maintained that it was the catholic spirit that alone could grapple with the evil of his times.

It was not long before Moorhouse attacked secular education, and seeking the co-operation of other churches he made efforts to include a schedule of Bible lessons in [46/47] State Schools, declaring that "if you sow secularism, you will reap irreverence and immorality." (61). He felt it was calamitous that the Bible was not taught in the system of "free, secular and compulsory education." He rallied churchmen of all denominations, bombarded the press and summoned meetings. However, the Roman Catholics demanded separate grants for their own schools. This the Bishop was willing to concede, but others were not and withdrew. "All the Nonconformists went with me," he writes, "till it came to the question of giving a separate grant to the Roman Catholics, and then the Wesleyans in a body left us, 'not,' they protested, 'because they loved Christ less, but because they hated Rome more'. Nothing will induce me to join in a bigoted howl against Rome," (62). But for this the Bishop would have succeeded in his endeavour to introduce Bible lessons into the State Schools. "The hatred of Rome here is incredible. I could have gained my object long ago but for this." (63). Nevertheless, an important outcome of the Bishop's efforts was the increase and improvement of the Sunday Schools of the Diocese. In 1876 there were 164 Sunday Schools with 19,215 scholars on the roll, and when he sailed for England they had increased to 324 schools with 29,084 scholars on their rolls. (64). The Bishop's methods were surprisingly modern and thorough.

Next to his educational reforms, Bishop Moorhouse, in his vigorous episcopate, showed that the faith of the Catholic Church had no need to retreat before the advances of science and philosophy. He took the platform as the champion of the Faith, rallying the forces of religion against the upheaval caused by the scientific theories of evolution. He had made himself familiar with the general results of critical and scientific research, and gave hearty recognition to them, believing them to be among the many ways in which the Divine purpose is fulfilled. Of all his labours, none perhaps were of such real value as the yearly course of lectures he gave. Delivered at first in the Cathedral on Wednesday afternoons, they were finally delivered in the Town Hall to packed audiences of three to four thousand people. "They have almost brought about an intellectual revival and have inspired hundreds with a desire for a more scientific theology," wrote the editor of the Argus. (65). "Other men may surpass him in critical [47/48] insight and mere book learning, but we cannot conceive it possible that anybody can be found to present the results of his criticism in more fascinating, constructive and popular form . . . he has quickened the intellectual and moral life of the community," runs another appreciation of these lectures. Moorhouse claimed the attention off the whole thinking community. Tolerant of differences, anxious to co-operate wherever possible with all labouring for good, he became a moral no less than an intellectual power in the community, and though his plain speaking was at times unpalatable, his earnestness and singleness of purpose soon dissipated misunderstanding. He sought to the Bishop of his Diocese, not of any party, and his ecclesiastical position was that of a broadened Evangelical.

Moorhouse undoubtedly preserved the individuality of his own church, but by his catholicity of sentiment, he also attracted other denominations. He appeared to hate sectarianism with a whole-hearted hatred, and to feel the divisions of the church as only those who love the church can feel them, and promoted reunion. He felt that it was "what the newspapers call our miserable sectarian differences," that had banished the Bible from the common schools, that had starved the clergy in poor country districts and wasted energies, and that had "weakened our hands in the conflict which we have to wage today against an extreme unbelief." Not only that, but it had disturbed the faith and harassed the feelings of the younger and more thoughtful members of the Christian Church herself. "We have opposed to us a creed," he declared, "which sets before us a sensual world as sole reality, matter without a mind, laws without a purpose, man without a future, the universe without a God, and we, we are mad enough to wage a fratricidal war within the very bosom of the Church itself." (67).

St. Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne, is a monument to Bishop Moorhouse, and its central tower is dedicated to his memory. Within three years of his arrival, the foundation stone was laid on April 13th, 1880, and during his episcopate he raised over £100,000 towards its building. He was responsible for its present site, as against the projected alternate sites of St. James' Old Cathedral, and St. Peter's, Eastern Hill. The Cathedral was finished with the exception of the central and western spires in 1891, during [48/49] Bishop Goe's episcopate, and the final spires were completed during the episcopate of Dr. Head (1921-41). The Cathedral was designed by the English architect William Butterfield, and the building is one of complete symmetry and great beauty.

Moorhouse also took up Perry's mantle in looking towards a framework for the Constitution of the Church in Australia, and 1882 found him chairman of General Synod at Sydney, dealing with that great question. "We had to settle the conditions of the Primacy," he wrote, "and conciliate the interests of the Dioceses, and to steer clear of the disquieting question of Letters Patent." (68). The past history of these problems had been discouraging, but, said Moorhouse, "I believe we settled our Constitution on primitive lines, and in such a way that no deadlock can arise in the future. Letters Patent and all State Churchisms we cast to the moles and the bats. And we have proved that the Church has power, on the lines laid down by the Ante-Nicene Fathers and Councils, to deal with her difficulties in her own way." Moorhouse, too, maintained freedom of debate both in the General Synod and in his own Assembly as a body of free Christian men legislating for the welfare of their Church. He was also instrumental in the holding of the first Australian Church Congress held in Melbourne under his presidency in 1882.

Like Perry, Moorhouse became well known for his pastoral and visitation tours over the whole of his vast diocese. These took two and three months of each year, for he pushed the ordinances of the church to every corner of his diocese. Gippsland clergy felt his annual visitations to be "the light of the year," and remembered his "long unwearied journeys through difficulties of travel almost indescribable, even to the remotest and most inaccessible portions" of the country. Moorhouse always liked to get down to the bed-rock of character, the importance of which he held to be greater than that of intellect. He loved "mixing," just as he loved the free air and the big solitudes, for he was a vigorous walker, loving scenery and writing enthusiastically about the charm of the colonial life in the bush. "There are some grand men up in these solitudes," he wrote, and he appreciated that in the rank of the clergy in country and mountain districts, "he found some of the most devoted ministers in the colony." (69). In spite of [49/50] the fatigue he loved his country work, and during these tours he travelled incessantly, preaching and speaking every week-day, and on Sundays two or three times. A typical extract of one of his letters reads: "Drove over 65 miles of tremendous country with the aid of three relays of horses to get to Melbourne, doing duty at two places on the way. Sat up at night to prepare for Wednesday lecture. Next day worked hard at lecture till 4 o'clock; delivered it at 4.15. . . . I am afraid you will think I have caught the Victorian habit of blowing; but I assure you I don't say these things to boast." (70).

During one of these visitation tours he came on a mob of thirsty cattle lowing round an empty trough. As it was Sunday, the herdsmen had given themselves a holiday from pumping, and had retired to their homes in a neighbouring township. "At once the Bishop took off his coat, turned up his sleeves, and did half an hour's hard pumping till the cattle had had their fill." When the news spread of what he had done, respect for the energetic bishop was certainly not lessened. (71). During that same tour an attempt was made by the infamous Kelly bushrangers to kidnap Moorhouse, to carry him up to the mountains and to demand a ransom, because of the way he had influenced public opinion against their depredations. Unknown to the Bishop, some of the Kelly supporters, fearing that the capture of the Bishop would damage the bushranger's cause, had "tipped" off the police, who discreetly escorted Bishop Moorhouse through the troublesome area. He himself, did not know of the plot until he arrived back in Melbourne.

Out of Moorhouse's visitations grew a system of rural deaneries, by the subdivision of the archdeaconries and the creation of a body of rural deans through whom the Bishop could administer to the outlying districts and keep his finger on their pulse. Moorhouse was indefatigable in the administration of his diocese, and one of his great objects was to raise the tone of religious worship, whether in town or country. He was not a man to let things slide, and while, with his judicial manner, his dislike of rambling talk and his habit of going straight to the point, he often seemed unsympathetic, none the less he was a man of rare power, whose external calmness indicated the self restraint of a nature inclined to impetuosity. While not wasting [50/51] sympathy on finger aches, mental or physical, he had it in plenty for those who suffered real trials. He had a tonic effect on his clergy, by teaching them to be more self-reliant. As he said once, "really the church people here crawl about with such craven chests, apologizing as it were for their principles, that I thought it would operate as a tonic to avow them boldly once in a way." (72).

Not only did the church, both in and beyond his diocese, benefit by Moorhouse's leadership, but also the world of secular affairs. His outlook was wider than ecclesiasticism and his interest extended to all that could interest man as man. During his visitation tours he was, for instance, interested in agricultural questions, soil, forestry, the methods of the growth of crop and the supply of water. He, in fact, brought the question of irrigation to a practical development after being impressed with the distressing drought of 1879. Kyabram remembers him, when land in the Goulburn valley was worth scarcely 25/- an acre, as the pioneer apostle of irrigation, and his plain speaking to a deputation asking for prayers for rain, suggesting that they should frankly confess their past neglect and lack of foresight, and that they should resolve to conserve future rainfall, played its part in the establishment of the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission.

He was ceaselessly occupied with all social and philanthropic questions, and also, in the words of the Governor of Victoria, Sir Henry Loch, "largely aided the Federal Movement." (73). During the political crisis of 1878, when Civil Servants were dismissed from their positions, Moorhouse, while keeping clear of political controversy, protested on moral grounds against the injustice, declaring that a "democratic government has done acts among us as unjust as were ever perpetrated in the worst excesses of the French Revolution." (74).

Moorhouse was also grieved at the low state of social righteousness in Victoria, and led a crusade against it. He tried to stir up public opinion against gambling, drinking, and immorality. During his episcopate, Sister Esther, of the House of Mercy, Cleaver, England, became the first worker in the Diocesan Mission to the Streets and Lanes, now known as the Community of the Holy Name. He aimed "to lift people high above the meanness of mammon [51/52] worship, and the pettiness of mere social cringing and toadyism."

In January of 1886, Moorhouse was translated to the Bishopric of Manchester, amidst widespread regret. His brilliant episcopate of nine short years had cast Bishop Perry's longer episcopate somewhat into the shade by its dash and splendour, through Moorhouse's ability in organization, his originality and independence of thought and his foresight and skill. Nevertheless there were but few considerable additions to the general framework of the organization that Perry had built. The Cathedral, the Theological School and Janet Clarke Hall at Trinity College, the Bishop of Melbourne's Fund, and the Sunday School Association were the only perfectly new institutions. But he did indeed consolidate the pioneering work of Perry. Statistics show an all-round rise in diocesan affairs, in some cases double and even treble. (75).

It is primarily as Defender of the Faith that perhaps Moorhouse may be known. His pride was, that though the Church of England had perhaps "known calamity and defeat in its long history; stain and dishonour it has not known." (76). Manly by disposition, despising all affectation of sanctity, his faith was firm, and his soul seemed to rise above the things of earth and catch glimpses of spiritual realities. His final resignation in England in 1903, and his ultimate death in 1914 at the age of eighty-nine, deprived the Bench of Bishops of one of its wisest and most learned members, and was a heavy loss to the Church of England. The Moorhouse Lectureship at St. Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne, is dedicated to his memory.