TO Charles Stuart Perry (1807-1891) must be given the title of the great pioneer and builder of the Church in Victoria. The period of his episcopate, 1848 to 1876, covered the formative period of both the Church in Victoria and life within the colony itself. He bequeathed an edifice to which others have added, and it is a tribute to Perry himself that no breaks have been found in its walls. He showed great moral courage and foresight in sharing the government of the church with the laity--he was in fact the first bishop to invite his brethren to share in that government; and that at a time when Europe was engaged in three revolutions; and he built up an educational fabric in the community in which he was placed. He was immensely loyal to his church, but it was his singleness of aim that most commands attention, and that in a period when makeshift was almost a rule for Australian Colonial politics (29), and public men worked under urgency coping with many pressing situations at many levels and had not the time or the means to be systematic and expert planners. Perry's singleness of aim and logical mind were of immense value to a young Church faced with difficult problems. These were those of disestablishment, the finding of a recognized constitutional basis for the government of the young church, of meeting wisely the growing tide of liberalism in education, and the materialism so easily produced by the comparatively unfought-for wealth in this new colony.

When Perry came to Melbourne it was not a "happy valley," according to an eyewitness. (30). "The maxim usually adopted is nothing for nothing," and the "spirit of ostentation and competition exists to a pitiable and ludicrous extent . . . . formerly low cunning and chicanery existed and were practised to a frightful extent." (31). However "the contrast between the earlier and the present state of society is very visible and a higher tone of society is gradually spreading," and "it ought to be remembered [33/34] that this improvement is due to the arrival of a Bishop in the presence of Dr. Perry, a man in whom are united the highest learning, humility and piety . . . . in the strictest sense the Bishop is to be distinguished as a working minister; already he has ridden a distance of 100 miles into the interior." (32).

Perry worked steadily and faithfully for the Church and the community throughout his whole episcopate, and when he left the colony in 1874, there were 90 clergymen and 169 churches in his diocese, and a distinct following of a quarter million people equal at that time to one third of the population of the colony.

In the forties, Melbourne was noticeably a churchgoing town, and in the period 1838-51 the pulpit, comparatively speaking, gained a stronger hold than it has since been able to maintain. An immediate cause of the loosening of its hold, was the discovery of gold, which had three important effects on the history of the church in this colony.

The first effect was a great increase in immigration. (33). A variety of windjammers brought nearly all classes of society, except for clergy, to the colony; "the famous and the infamous, the scions of great names among anonymous masses, fugitives, remittance men, adventurers, labourers, investors, intelligentzia, ne'er do wells, even men who had used the miner's pick and cradle before." (34). The effect was a decline in the proportion of clergy to the population. Perry, realizing the seriousness of the situation appealed to the missionary societies in England, and subsequently formed his Gold Field Mission. He keenly felt his heavy responsibility, and appealed to his flock to employ all their influence "for restraining disorder and iniquity." He also lifted up his voice on behalf of the Government of the colony, stating that "it was wholly unbecoming Christians, that they should regard Government as responsible for all our difficulties, as though our rulers could by their foresight and prudence have provided against such an emergency." Whereas, "it is not our business to meddle with politics, it is our business to dissuade our fellow colonists from indulging a mischievous spirit of discontent, which, so far from mitigating, can only aggravate the evils of which they complain. The Government were suddenly placed in a most anxious and awkward position. . . . it [34/35] especially becomes a Christian to endeavour to strengthen, not to weaken, the hands of our rulers." (35).

The second effect of the gold discoveries was an immense shifting of the population, and it was no easy matter for the Church to transfer her ministrations where they were needed most.

Then again, thirdly, "Gold Fever," meant a deterioration in the ideals of the people, a "frontier-inspired" restlessness unfavourable to the growth of religion. It was difficult also to create enthusiasm for religion in people whose purposes were frankly materialistic. Bonwick says "the Australian Gold Fields put to the blush the very fairy tales of old. Men were flitting around in various disguises, and heads were popping up in various holes about one." It was natural that there should not be any great progression in social virtues and refinement, but none the less there was no great crime, and life and property were safe. The manner of Sunday observance was highly creditable, and a congregation was readily collected when an interest was shown in the religious welfare of the miner. The miners themselves appreciated the security and peace given them by the stand of the Government in refusing to sanction the sale of alcohol at the diggings. Still there were "sly-grog" shops, and consequent riot and bloodshed in their vicinity, at "Murderer's Flat" and "Chok'em Gully." However, the more serious social evil was the breaking up of families. The future condition of the colony greatly depended on the efforts of the few and the unselfish amidst the whirl of excitement and the rush for wealth.

Throughout that period of the gold fields, Perry "that most excellent of men" (36), kept his ideals and vision, for the romantic period of the colony's existence was soon to come to an end, and there was trial and struggle ahead. Victoria had started on her career with landed estate of many millions in the shape of her pastoral industry, and beneath its surface enough gold to make her the largest producer of the yellow metal in the world. (37). It needed men of resoluteness and integrity who would waive their personal ambition by devoting those qualities to the uplifting of the community. Such a leader was Perry. "Much of the harmony that prevails among the various Christian communities is due to the moderation and Catholic charity of that eminent and remarkable individual," remarked a [35/36] contemporary. (38). "The Church of England," he continued, "is peculiarly happy in her Bishop, for he combines all the qualities required for a Colonial Bishop's office, demanding utmost prudence, sagacity and zeal; he is distinguished by attainments of the highest order . . . . . I think he is the only public man in the colony who has escaped the public censure." The Dean of Melbourne, the Very Reverend H. B. Macartney, eloquent and impulsive, but trustworthy and devoted to his work, was worthy of being second to such a chief. As a body the rest of Perry's team of clergy certainly "need fear no comparison with the average of the clergy in England, either in intellectual power or in Christian devotedness." (39). With the Bishop and his early team, there was that oneness of heart and action that "attraction of cohesion" which so remarkably distinguished the first centuries of Christianity from all subsequent ages.

That same spirit of personal holiness and logical accuracy (he was the first mathematician of pre-eminence to set foot in Australia) and zealous moral strength which Perry displayed, had been evident in his life in England. He it was, who, when a Fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge, devoted his private fortune (he was the son of a ship-builder), to the ecclesiastical needs of the town and built no fewer than three large churches. He was "one of the most pious and generous men Cambridge has ever known." (40). Besides building Great St. Andrews, he renounced the comforts of college life and in 1839 took charge of Barnwell, a hopeless slum area with a reputation for vice of every kind. He built two churches at his own expense, inspiring others to work and invoking the help of a band of undergraduates. The tribute paid to Perry on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of his consecration, shows that he had not lost any of his qualities during his sojourn in Victoria. "Among a people singularly.independent in thought, restless in action, and impatient of restraint, who had broken away from home and home associations, it was your work to stand upon the old paths, in a new world to rear up the fabric of the ancient time-honoured church of the old country." (41). This tribute does not necessarily mean that Charles Perry was a conservative only, for he was one of those who have been able to reconcile liberty with loyalty, and he stood at the historical [36/37] cross-road in Victoria with clear vision. It was not for nothing that his Metropolitan, Bishop Broughton, criticized his "spirit of independency" when he convened a democratic gathering to discuss "the expediency and mode of organizing diocesan synods and conventions" in June of 1851. Perry's cultured Evangelism too, made him a special power in the counsels of the Church, as was evidenced in the vital 1850 Conference of Bishops, summoned by Broughton at Sydney. The importance of this conference of the six Australian Bishops cannot be over-estimated, for Australia, since it had ceased to be essentially a convict station, was bound to develop on democratic lines, and the autocratic powers conferred upon Bishops by Letters Patent were hardly suitable in a new colony like Australia.

Perry was a brilliant scholar. After leaving Harrow, he graduated at Cambridge in 1828 as Senior Wrangler, and also as a first classman in the Classical Tripos. He subsequently became Fellow and Tutor of Trinity College, Cambridge, after admission to Holy Orders in 1837. Although in no sense a man of the world, Perry, the gentle scholar, faced the inevitably rough pioneering experiences that Melbourne and Victoria offered in their infancy, without any slackening of his zeal. Mrs. Perry was close beside him. In those days, a bishop travelled throughout his diocese mainly by road; there were few railways and not many good roads. Mrs. Perry, in her Diary (42), has left us graphic descriptions of the journeys of the Bishop in his pastoral visitations. Writing to friends in England, Mrs. Perry remarked that "we have often pictured to ourselves your astonishment could you have seen us. Two hundred miles have I travelled tandem without the slightest fear or discomfort; whereas in England I should as soon have thought of flying as trusting my precious person to such a vehicle." (43). And again, "our next stage, of fifteen miles more, was a very fatiguing one being a constant succession of very steep, and often very long, hills; so steep some of them were that I thought it must be impossible not to slip over the horse's head in going down, and over his tail in going up, but fortunately, we did neither." (44). Her lively pen was quick to note the many beauties of the countryside, with which she was entranced.

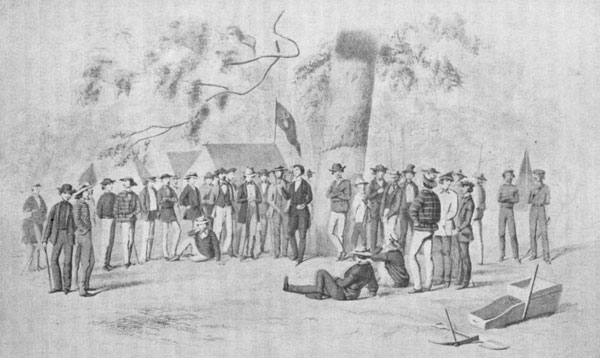

Throughout his episcopate Perry travelled the length and breadth of his huge diocese, from Albury to Gippsland, [37/38] travelling sometimes fifty and sixty miles a day "in a manner which we both prefer in this country, viz., Mrs. Perry in a tandem and I on horseback." (45). Bishop Perry also visited the Gold Fields, holding services himself. "Charles amused me greatly," writes Mrs. Perry, "by saluting every individual with a touch of his hat and 'Good morning.' From some he got a civil return, and from others a broad grin. We took a great quantity of tracts with us, which were gladly received by all." (46). At Forest Creek, there were services. "During Sunday C. held three services," continues Mrs. Perry. "The first, consisting of morning prayers, with the Litany and a sermon, at eleven o'clock; the second of the Litany alone with a sermon (three o'clock); the third, of a portion of the Communion service with a lecture (five o'clock) . . . The congregation consisted of about two hundred persons, morning and evening, and about four hundred in the afternoon. They behaved with perfect propriety during the service. . . . C. was compelled to perform the afternoon service in his riding dress, and his pulpit being the stump of a tree, which afforded rather a precarious footing, you may imagine that he did not present a very clerical appearance." (47).

Perry, the scholar and Bishop and shepherd of his flock, indeed shared the hardships and perils of the flock. He spent two months at the Gold Fields, and in consequence "fell in with many scores of people, all on their way to obtain a share of the treasure." "On one occasion," writes Mrs. Perry, "C. having determined to ride part of the way, was on horseback when he saw a company at some distance before him, and began to look out some tracts for them. While he was thus engaged, trotting along at the same time, his horse stumbled and fell with him, throwing him forwards on his face, and actually rolling over his back as he lay along. Most fortunately the dust was very deep, and furnished a soft bed for him to fall upon; and providentially the saddle of the horse appears to have rested exactly upon his back, so that, although the weight made him breathless for some moments, it inflicted no other injury than a bruise on the loin, and another, a slight one, on the chest. C. says it was the most remarkable escape which he remembers to have ever experienced. You may imagine what a figure he was when he rose from his sprawl in a bed of dust two or three inches deep. His appearance, [38/40] as I had previously heard he was unhurt, called forth a hearty laugh from me. We had great cause for thankfulness that he was able, after such a fall, to resume his seat in the carriage, and drive the remainder of the stage with very little inconvenience." (48).

Besides his pastoral visitational work, Perry also carried on a great deal of pamphleteering, and he spoke on many public questions. He would not however, meddle with politics. As early as 1849, he declared "I am determined, God helping me, to know no politics or parties, in this place, but to approve myself to all alike as a Minister of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. . . . I earnestly deprecate in this province any admixture of political and party feeling with that zeal for the truth of the Gospel which ought to animate the bosom of every true Christian." (49). He even went so far as to state in reference to the Loyal Orange Association, that it would "afford me heartfelt pleasure as a Protestant Bishop to see your association dissolved . . . upon general principles." (50).

In 1850, Perry founded the Church of England Messenger with himself as editor. Its object was to "promote true religion and piety among the inhabitants of this Province." The principles upon which he wished to carry on "are those of Christian charity, but not latitudinarian indifference. They are bound to set forth Church of England doctrines and constitution." (51). Except for some early changes of name, this journal has carried on uninterruptedly until the present day.

Perry, as an Evangelical, had strong views on the Baptismal Controversy which caused fresh secessions to Rome from the Church in England, and also on the authority and the inspiration of the Bible, and these found expression in many of his pamphlets. One was the intellectual event of the day, namely his pamphlet on "Science and the Bible," dealing with the theories of Darwin, in which he clearly set before the community the points of conflict between the traditional interpretation of the Bible and the then recent, scientific theory. Although it was a rear-guard action, none the less his views are thoroughly clear, logical and uncompromising. It may perhaps be said "that he was not in touch with modern thought or interested in the problems which were beginning to distract the Episcopal dignity of the land he had left" (52), but [40/41] he indicated, and his successor, Bishop Moorhouse proved, that the Church of England is not bound to intellectual positions incapable of defence, and that she is the friend of learning and the critical spirit, having behind her the force of a great historical tradition. There can be no doubt that Bishop Perry was one of the great churchmen of the nineteenth century, and that he rose to his pioneering task in this country magnificently.

Towards the end of his episcopate he looked forward to the building of St. Paul's Cathedral, but although he initiated the movement, he none the less felt that the foundation of Trinity College was the more important immediate task. (53). After the labour and effort of many years he succeeded in dividing his Diocese and founding that of Ballarat, which contained an area nearly one-half of the whole State. He seems to have regarded this work as the crowning effort of his long episcopate, for after travelling to England to assist in the selection of the new Bishop for that diocese, he made preparation for his own retirement, as he was fast approaching seventy years of age. After a year in England he resigned in 1876. Queen Victoria recognized his work in Melbourne and in Victoria by making him Prelate of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. He was for some time Canon of Llandaff, and died in 1891 at the age of 84 years.