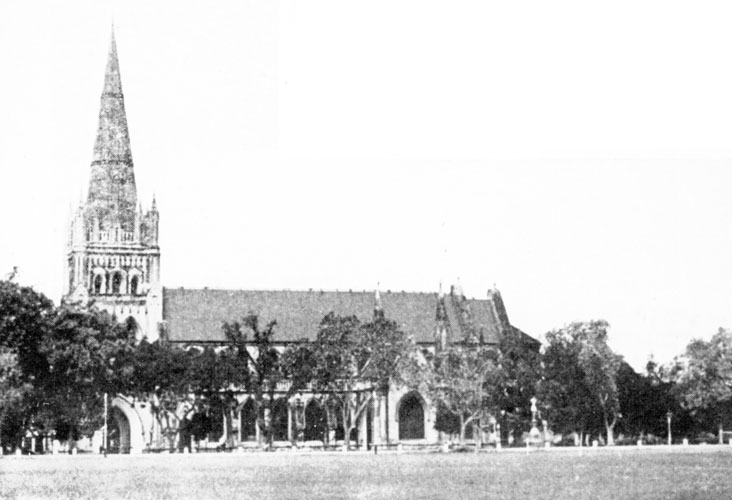

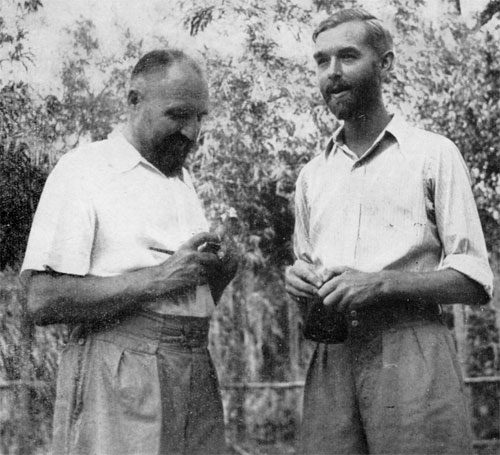

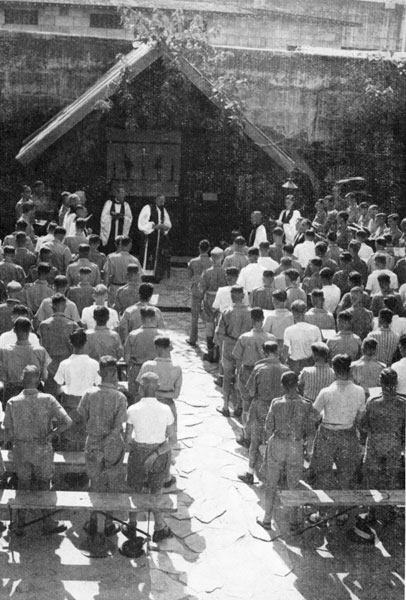

Before the War: The Rev. Eric Scott on tour with the Rev. John Lee, a Chinese priest. Before the War: The Cathedral at Singapore, which remains unharmed. The Bishop of Singapore with Lieut. Ogawa in 1942, before internment The Bishop with the Rev. John Hayter in 1945, after liberation. Confirmation for Prisoners-of-war in Changi Camp after liberation. The Bishop of Singapore with Chinese girls after liberation.

In population and area the diocese of Singapore is one of the largest in the world. It comprises the whole of Siam, Malaya, Java and Sumatra, and a number of smaller islands. But in number of clergy it is one of the smallest. The total complement is normally about thirty-three, exclusive of Services Chaplains. Of these all but two or three work in Malaya, and this booklet will concern itself only with the work of the Church in that country, with due apologies to the rest of the diocese.

Malaya is, in size and shape, comparable to Great Britain without Devon and Cornwall. From the Siamese border to Singapore is about six hundred miles by road or rail. The main trunk road and railway line run the whole length of the peninsula, keeping fairly near the west coast. They cross the border from Siam into Kedah, the little State of Perlis being tucked away in the north-west corner. Kedah is flat country, largely given over to the growing of rice. To the south lies Province Wellesley, a narrow coastal strip, with the island of Penang lying off the coast. All these are one parish, which also includes the whole of Sumatra, and the west coast of Siam, and there are two European priests, one Chinese and one Indian, working in it.

Moving further south we come to Perak, the Malay word for silver, but its chief product is tin, although a great deal of rubber is also grown there. Perak is divided into two parishes, each staffed by one European priest and one Indian. South of Perak is Selangor, the chief town of which is Kuala Lumpur, where the Chaplain has one Indian priest and two Chinese working with him. Like Perak, Selangor is well developed country, and so is Negri Sembilan to the south, where again one European and one Indian priest are stationed.

Pahang, lying to the north and east, and stretching right to the east coast, has hardly been developed at all, though like the rest of Malaya, it is rich in mineral ore of many kinds. It is mountainous jungle country, much of it a huge game reserve, and the two chief Malayan hill stations [3/4] are both in this State. There is no priest stationed in the whole of this vast area, nor in the two east coast States further to the north, Kelantan and Trengganu.

The largest of the States, Johore, in the extreme south of the Malayan peninsula, also has no resident priest. Most of the State is included in the parish of Malacca, a bite taken out of Johore at its north-west corner, where there are one English priest, one Indian and one Chinese.

Finally, joined to the mainland by a concrete causeway half a mile long, which carries the road and railway, there lies Singapore Island, roughly the same shape and size as the Isle of Wight, with the naval base to the north and the city to the south. Of the diocesan clergy no less than six European priests, four Chinese and three Indian are resident on the island, as well as the Missions to Seamen chaplain. The population of the island is only threequarters of a million, out of five million odd for the whole country, so this may seem out of proportion. But two of the European clergy are schoolmasters, and so is one of the Indians, while one Chinese and one Indian are honorary.

The stranger arriving at Singapore might easily make the mistake of thinking that he has come to a Christian city. The Anglican Cathedral occupies the most central site in the town, originally set aside for it by Stamford Raffles, and not far off are an American Methodist Church, a Presbyterian Church, the Gospel Hall of the Plymouth Brethren, and a Roman Catholic Church, with the Roman Catholic Cathedral not far away. All told there are about fifteen Anglican places of worship on the island, and corresponding numbers for the other denominations. But the great majority are primarily for Europeans. Many English-speaking Asiatics attend them, but of course the population of the island consists mainly of Asiatics, who speak little or no English.

Anglican missionary work in Malaya is small compared with that of the American Methodists and the Roman Catholics, and in some parts with that of the Plymouth Brethren and the Presbyterians.

To anyone arriving in Malaya for the first time the strongest impression is the strange mixture of races which one finds there. The Malays form one of the largest racial [4/5] groups, and together with the Sakais--shy, hill-dwelling, pygmy tribesmen, few in number--are the true people of Malaya. But the Chinese are very nearly as numerous. Although British occupation of the country since the middle of the last century has meant Chinese immigration on an increased scale, they have been there for a considerable number of years.

The Indian community does not compare in size with either of these two, but forms a substantial part of the country's labour force, particularly on the railways and rubber estates. The European, and Eurasian and Ceylonese communities are small, as also are the Arab and the Jewish. Speaking generally, the towns are the home of the Chinese and the country districts of the Malays.

The proportion of Christians in the country compares favourably with the proportion in other countries of the East, yet it is low. Missionary work is confined to the two million Chinese and the one million Indians who inhabit the peninsula. Among the Malays themselves, who slightly outnumber the Chinese, there has been little serious attempt at Christian work, and the Government's agreement with the Sultans has been commonly interpreted as precluding evangelistic work among them.

Missions are usually supposed to stand on three legs: the Church, the hospital, and the school. Malaya has a firstclass system of Government hospitals, which needs little supplementing, though there are two hospitals in Singapore run under the auspices of S.P.G.: St. Andrew's Hospital, in the poorest part of Chinatown, for women and children; and in a lovely position by the sea, some distance out of the town, there is an orthopaedic hospital, opened in 1939, the only one of its type in the country. The only home for the blind is also an Anglican institution, St. Nicholas' Home in Penang. But in the sphere of education, though there are many fine Government schools, there are at least as many "grant-in-aid" schools which receive financial help from the Government on condition that they conform to certain standards. The great majority of "grant-in-aid" schools, in which the medium of instruction is English, are run by Christian bodies, and so are some of the vernacular schools. The Church of England has a fair share of them, though not enough. The new buildings of [5/6] St. Andrew's School, in Singapore, are as fine and as well equipped as those of any school in the country, though they have not been improved by being used by the Japanese as a rice store for three and a-half years.

One of the handicaps from which a diocese with so small a staff suffers is that the turnover is not sufficiently rapid to support a Theological College. All the clergy have either been brought in from elsewhere or, if locally born, have had to be sent to India or China for training. For a few years the Community of the Resurrection took a small number of theological students at Kuching, Sarawak, but unfortunately that venture had to be closed down. Apart from Borneo, the Singapore diocese is very isolated. Our next nearest neighbour is the American diocese of the Philippine Islands; of our other neighbours, Hong Kong looks naturally to China, and Rangoon to India. The ties between Singapore and Borneo are close--they were one diocese until 1909--but it is difficult to see how they can ever become part of a province. This isolation has many drawbacks, one being that the two dioceses seldom get their fair share of publicity. Everyone has some sort of picture of India, Africa and China, and the work and needs of the Church there are well known. Yet Malaya and Borneo are countries for which we have a special responsibility, not only as Christians, but also as Britons, because they were promised British protection, and did not receive it in their hour of need. As we shall read in the later chapters of this book, their people have a grand record of loyalty and devotion during the Japanese occupation, and the Christians stood firm in the Faith, often at great risk to themselves.

We have been taught much by our common sufferings under the Japanese. Before the war we had perhaps gone a little stale. We were more anxious about keeping things going and making ends meet than about going out into the highways and hedges. We had not enough imagination about the Church's possibilities; we had too limited an idea of what is required of a man when he becomes a Christian. There were certain grand things about the Church in Malaya--it was a wonderful mixture of peoples, and there were no barriers of race or colour within it. We all worshipped at the same altar in the House of God, [6/7] but we were not so sure about all eating at the same table when we got outside. We were proud of what we had achieved, but a little fearful over launching out into the deep. We were too sectional, took too little interest in each other, did not take enough trouble to overcome barriers due to differences in language. (Services were held in seven Chinese dialects, three Indian languages, Malay, which is something of a lingua franca, and of course, English.) We were not active enough in social service, and were too absorbed in activities inside the Church to play our full part in the life of the community. There were all sorts of reasons for this state of affairs. We could make most satisfactory and excellent excuses and explain exactly why it was impossible that things should be different. But the fundamental thing was that we were too complacent and too timid. What would happen if the Spirit of God was really allowed to fill His Church? I am afraid we had not quite faith enough to see.

Yet the Church had life in it, and great possibilities. Numbers were increasing slowly, and many projects were under way. We had great hopes for the future and many plans and schemes about what we were going to do.

The Bishop, the Right Rev. John Leonard Wilson, formerly Dean of Hong Kong, only arrived in the diocese four months before the outbreak of war in the East. He was in Bangkok three days before the opening of hostilities, caught the last plane to return to Malaya, and had to cut short his two-month tour of the diocese by only one day. He had, even during that short time, begun to formulate plans for the future.

But when, on December 8th, 1941, the Japanese attacked Malaya, and to our dismay began advancing rapidly down the peninsula, it seemed that all our hopes were to be dashed and all our plans frustrated.

II. "WE GAVE OUR TO-DAY." Early in the morning of December 8th, 1941, the telephone rang in the house in which I was staying at Kuala Lumpur. Bombs had been dropped on Singapore, and the Japanese had landed at Kota Bharu in the northeast corner of Malaya. The Japanese had entered the war.

Whatever may have been the thoughts of senior service officers, the attack, when it came, was unexpected by the great mass of the people of Malaya. And not only by the civilian population. Angus Rose, in his excellent book, Who Dies Fighting, was able to write of the situation only twelve hours before the attack started, when a Japanese fleet was known to be in the Gulf of Siam: "There was a lot of conjecture as to whether this move on the part of the Japs was not all bluff; and the majority of officers who had personal experience of the Japs in China were convinced that there would still be no war."

Even after we knew that the fight had begun it was impossible not to feel, as we thought, justifiably confident. But the news that H.M.S. Prince of Wales and Repulse had both been sunk was an almost overwhelming blow. The war less than three days old, and now this tragedy. For the first time we realised the scale of the attack and the danger in which Malaya stood.

From that moment until the end, things happened quickly for us in central and southern Malaya. The main Japanese tactics soon made themselves clear. The landing at Kota Bharu and operations down the east coast were never more than on a small scale. I he main attack was from Singora, in southern Siam, across the peninsula into Kedah, and from there down the west coast, through more highly developed country, with excellent road and rail communications, neither of which existed at all on the east coast.

Penang was gravely threatened, and early in the morning of Sunday, December 16th, British women and children were sent down to Singapore. Some days later all British men were also evacuated from Penang, and they too went south to Singapore, by sea, as the land communications were threatened by the speed of the Japanese advance. [8/9] No satisfactory explanation has yet been given for the manner of this second evacuation. Three men--the Rev. Eric Scott, priest-in-charge of St. Mark's, Butterworth, on the mainland, Major Harvey of the Salvation Army and Dr. Evans refused to leave, although ordered to do so. But the completeness of the evacuation caused untold suffering to the people of Penang. The Japanese, not realising that we had withdrawn from the Island, continued their bombing raids, and the densely crowded areas of the town of Penang had previously been heavily attacked. Looting was widespread, all public services broke down; the labour force melted away, with no one to control it, and bodies remained for days in the streets or under debris. Harvey and Eric Scott continued working in the camps of temporary hutments outside the town, feeding and housing many hundreds who had been made homeless or who had taken refuge there from the bombing. But in the town there was chaos.

The position was saved by a Ceylonese journalist named Saravaramuthu, an Anglican. His conduct then and during the months that followed was of the highest. He organised volunteer police patrols, himself hauled down the Union Jack, ran up a white flag, and broadcast a message to the Japanese urging them to come in and establish order. Questions were asked in the House of Commons, and he was openly censured as a co-operator, but no one who was not in Penang at that time could possibly judge the situation. His motives were purely humanitarian and disinterested. This was soon proved beyond any doubt. Immediately after their arrival the Japanese tried to induce him to broadcast to the peoples of Malaya in areas still occupied by the British to urge them to hamper our retreat and welcome the invader. He refused, and spent many months in a Japanese jail as a result.

For a short time, Eric Scott was allowed free movement in the town, but was later placed under house arrest at St. Nicholas Home for Blind Children. He was not allowed any contact with the children in the home, but was permitted to hold services in the chapel, which the people of Penang were allowed to attend. Late in 1942 he was transferred to the civilian internment camp in Singapore.

[10] Meanwhile there had been much to be done in Kuala Lumpur. Civilians, mainly women and children, were pouring in from the north and from the east coast by car, lorry and train. For some of them billets had to be found, others were sent straight through to Singapore. There was much sadness and anxiety for them--there can have been few who had not left husband, father or son in unknown danger,--but their courage and patience were an inspiration to those who were trying to help them.

Shortly before the fall of Taiping the Rev. G. S. Clarke, one of the last to leave, drove down to Kuala Lumpur. He left during an air raid, and as he drove away from the front of the parsonage two bombs arrived at the back (which, perhaps, accounts for the fact that his car seemed to be entirely filled with pillows and hymn books!) His arrival in Kuala Lumpur meant that I was able to hand over to him and get back to Singapore in time for Christmas.

Before the war the Bishop had me appointed Chaplain to the Passive Defence Services--A.R.P. and the rest,--but now there was the even more pressing problem of the reception and billeting of evacuees. No one had realised the size of the problem, but with a great deal of hard work and endless improvisation, a situation which was threatening to become chaotic was reduced to some sort of order. We could at least say that, with the assistance of householders in. Singapore, the army authorities and countless helpers, no one, as far as we knew, was ever homeless. The organisation of which I was part, was dealing in the main with Europeans, but we kept in close touch with those helping Asiatic evacuees, and, in particular, the Chinese clergy at Holy Trinity Church did excellent work. The Rev. John Lee housed and fed a large number of people in the hall below the church.

Up-country the Japanese continued to press forward. Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur, Seremban and then Malacca fell. The Rev. Bernard Eales stayed behind in Malacca, as Eric Scctt had done in Penang, but was put in the civil prison almost immediately, before being interned in Singapore some months later. By means of constant requests he was able to obtain permission for the Rev. C. D. Gnanamani to visit the jail and hold Communion services regularly; and on one occasion, with watchers posted to give warning [10/11] of the approach of Japanese guards, he baptised a Chinese prisoner under sentence of death. This man was taken away a few hours later and did not return.

In Singapore, as the Japanese advanced further south, so bombing raids became heavier and more frequent. The first big daylight raid at the back of the town was made on January loth by a group of twenty-seven planes flying high--from now until the end that was the usual formation. Two bombs fell in the Archdeacon's garden at Cathedral House, and while he and Mrs. Graham White, who were in their shelter, were only shaken, Joseph, his Indian secretary, who was standing on the verandah watching the planes, was killed instantly. Other equally heavy raids followed, and with greater deadliness, as they were concentrated on the congested areas of Beach Road, Geylang and Tanjong Pagar.

For the next three weeks until the end came on February 15th, there was little rest for anyone. Ships were leaving crowded with refugees; bombing continued, oil fires at the Naval Base caused a heavy pall of black smoke which hung over the town for weeks. On the last day of January the Argylls, the last troops across, marched over the Johore Causeway with pipes playing, and a breach was blown, cutting our last communication with the mainland. The Japanese brought up their artillery and assault troops, and early in the morning of Monday, February 9th, they secured a footing on the island. Shelling and bombing by lowflying aircraft increased, casualties in the town mounted, and essential services became disorganised; but not for one moment did the Passive Defence Services waver. Whole chapters could be written of the work of the men and women of the A.R.P., A.F.S. and Medical Services. Young Chinese, Indians, Malays and Eurasians showed astonishing courage, endurance and initiative. A typical example was that of a young Chinese nurse who stayed kneeling beside a wounded soldier in an open corridor at Kandang Kerbau Hospital, while shells were falling on and around the building, shielding his body with hers, covering his ears with her hands.

Towards the end of the last week, when outlying districts on Singapore Island had to be evacuated, the two great military hospitals at Changi and Alexandra had to find [11/12 ] accommodation somewhere in the town. The Bishop had no hesitation in allowing the army the use of the Cathedral. I was there on the evening of Saturday, February 14th--less than 24 hours before the surrender. It was an unforgettable picture: the wounded lying in the nave and aisles (now emptied of their furnishings), doctors and orderlies moving about their work, the stillness broken only by the tread of boots on the stone paving and the low murmur of voices. Standing by the west door I looked into the shadows, studded with the glow of many cigarettes, and the occasional flare of a match, and then beyond the choir to the altar with the dull gleam of the cross catching the fading light. Here, in spite of the noise and fury outside, the crash of bombs and the roar of our own guns, was a great peace, and there was an overwhelming gladness that those walls, symbols of love and goodness and strength, should have been sheltering those to whom Christ himself would then have wished to be most near. The following evening (Sunday, February 15th), a little after 4 o'clock, when the news of the surrender had just come through, the Bishop held a great service in the Cathedral. He said afterwards that it was one of the most moving and impressive services he had ever attended.

So ended the battle for Malaya--short and utterly overwhelming. What lay ahead for us and for the peoples of Malaya? Perhaps it was well for us that we did not know.

III. "BABES IN THE JAPANESE WOOD." For some days before the fall of Singapore it had been impossible to move freely about the town. I had spent most of the time at the General Hospital where there was a great demand for voluntary helpers, and the Bishop and I moved there on the night of the surrender. On the following Wednesday the whole hospital had to be evacuated to a portion of the Mental Hospital some way out of the town.

On his way out there the Bishop called at the house of the Rev. Dr. D. D. Chelliah, who had formerly been the senior Asiatic assistant at St. Andrew's Boys' School. The [12/13] Bishop, expecting to be interned, made arrangements with him for the work of the Diocese as best he could, and we drove on. But on the following Sunday, February 22nd, the Bishop obtained permission to return to his house in the town with two other clergy. After discussing with the Archdeacon the question of who should go back, it was finally decided that the Rev. R. K. S. Adams and myself should accompany him. On the following morning we returned to Bishopsbourne. We remained free for thirteen months, until March 29th, 1943. The remainder of the European clergy and diocesan workers were interned.

Fortunately the looting at Bishopsbourne had not been very serious, and for the first few days we spent the time cleaning the house. We had little idea of what our position was likely to be, where we should get food or money, whether we should have servants, or what degree of freedom of movement we should be allowed. As it happened we had no need to be anxious. There was not a single day when we were without petrol for the car, although officially we were getting none from the Japanese. No restrictions were imposed on our movements until the beginning of December, when we signed a form of parole. Adams and I were ordered to be in the house by 8.30 p.m. But no such restriction was placed on the Bishop. The Bishop's Chinese houseboy returned after three weeks and stayed with us the whole time we were in Singapore. We had hardly been in the house a day when friends began to visit us with presents of food and money, and a special word must be said of the almost overwhelming kindness, thoughtfulness and generosity of our own Church people throughout the whole of the time that we were with them. We were receiving nothing in rations or in pay from the Japanese, and yet we never lacked for anything. There was hardly a day when a visitor did not bring us something--food, eggs, or money--although there were many who were finding it difficult enough to feed themselves and their families; yet they all, Chinese, Indians and Eurasians, regarded us as their responsibility. It was an entirely spontaneous response of affection and concern.

But far more than the material help was the help they gave us by their kindness and friendship. In some way they sensed for themselves our feeling of loneliness and [13/14] isolation. The sympathy and understanding which they showed, but seldom spoke of, were of incalculable value to us.

On the whole the Japanese behaved well towards the Churches--certainly much better than we had expected, and far better than in the other occupied countries. The Cathedral and all the churches in Singapore were undamaged, with the exception of Christ Church Indian Church, where the roof had been hit during the shelling and partially destroyed by fire; but it was soon repaired. Throughout the occupation churches remained open, and there was little interference with the conduct of services. The only restrictions were a ban on preaching, although Bible classes, study groups and Sunday schools were allowed to continue, and, naturally enough, we were not allowed to use the State prayers or hymns with a national flavour.

Their attitude towards education--and particularly religious education--in the schools was not so enlightened. All Mission schools were taken over by the Government and no religious instruction could be given. Their object was to create good citizens of Japan. The conversation of any two fifteen year-old schoolboys almost invariably showed how completely they failed, and there was a very large number of parents who refused to send their children to school at all.

But however much the Japanese may have secularised education, they not only professed, but acted upon a policy of religious tolerance, and they acted upon it in a far more thorough way than they seem to have done elsewhere.

We had expected much more positive opposition. The Church in Malaya has cause for deep thankfulness that it was not so. We ourselves--and I think, if truth were known, the Church as a whole should probably share the debt--had good reason to be grateful to a Japanese officer, Lieut. Ogawa, an Anglican and a keen Churchman, who attended the Cathedral regularly. He arrived in Singapore soon after the occupation, in the position of Director of Religion and Education. On one occasion he secured Adams' release from military police custody as soon as he was informed of his arrest on a charge of talking to prisoners of war over the fence of their camp.

[15] In September, 1942, I made this note in my diary: "Ogawa had been told to order us from Bishopsbourne (the Bishop's house), having fought and won a battle against our going to internment at Changi." It was he, too, who was responsible for obtaining permission for the Bishop to go to P.O.W. camps without an escort, for Confirmations. He gave the Bishop a letter in Japanese which not only explained fully who the Bishop was, and the nature of Confirmation, but went even further than that, requesting that he should be given opportunities of going into the camps to "cheer the spirits of the prisoners." A good many camps were visited in this way.

For many reasons it was desirable that, under the conditions prevailing, there should be close understanding and co-operation between the Churches and, with Ogawa's approval and support, the Bishop was instrumental in forming a Federation of the Churches of Malaya. It was in no sense of the word a United Church, as each of the Federated bodies--the Roman Catholics would have nothing to do with it--maintained their own services and kept their own identity, but it did provide extremely valuable opportunities for close co-operation between the Churches. Its three main spheres of common action were monthly services of united worship, mutual discussion and exchange of ideas in an attempt to arrive at a closer understanding of one another's point of view, and the setting up of an organisation for the relief of suffering amongst the peoples of Malaya, of whatever race or creed. The Federation, together with other voluntary relief organisations, was able to do a great deal to make up for the Japanese indifference to the needs of the destitute.

A word must be said of the Japanese attitude towards hospitals. The accommodation was hopelessly inadequate, and although Chinese, Indian and Eurasian doctors and nurses worked magnificently, they were, from the start, fighting a losing battle. Insufficient food, drugs and dressings were almost overwhelming obstacles, and it is sad to record that few of the children in the St. Andrew's Orthopaedic Hospital have survived. At the outbreak of the war, with the possibility of sea-borne landings, they were evacuated from one place to another four times before they were finally taken to the main block of the General [15/16] Hospital. On the last afternoon of the war they had an amazing escape. A large jagged shell-splinter, 8-in. long, smashed its way through the bunding, ricochetted off a window-frame to one of the walls and then down amongst the children on the floor. Only one child was touched--a very slight graze on the forehead. After the surrender they were transferred to the Mental Hospital buildings, and it was pathetic as we visited them there, to see children like Noel and John--always so cheerful, and the latter a world-beating draughts player of ten--now wasting away and dying.

For the greater part of our year in Singapore I was in charge of St. Hilda's Mission Church at Katong, always in the past an alive and active little church; and there, from small beginnings, we built up together a congregation with a markedly strong "family" sense. There were few people who had not some small niche in the organisation, and they worked admirably as a team. These stand out particularly in my mind: parish breakfasts in the room above the church; a Sunday school of over loo children; an unforgettable Christmas in 1942, finishing with a social in the school hall on Boxing night, with a Christmas tree of which the top had to be bent over as it was pushing up against the ceiling; 150 people listening to the Bishop and the priest-in-charge singing comic songs; a conjuring show from an international medallist; and a really beautiful and most moving performance of John Drinkwater's The Travelling Man, produced and performed by three members of the congregation. Here, and later at a children's party and at a Nativity play, for which the Cathedral was twice packed out, it was difficult to remember--we were only too ready to forget!--that we were in an enemy-occupied country.

All the Asiatic clergy throughout the occupation showed devoted service and it was most encouraging to hear their reports when they came to Singapore for a diocesan con ference in August, 1942. More of their story will be found in a later chapter, but in Singapore itself during the first year of the occupation, Anglican Church life was at a high level and attendance at church services remained good throughout. But mere numbers are never a true test of the spiritual health of the Church. Many found, possibly [16/17] for the first time, a real fellowship and community of interest in their Church membership. This was due in a very large measure to the work of the Asiatic clergy. The Rev. Dr. D. D. Chelliah, who carried the responsibility of the work at the Cathedral from March 1943 until the end, was for the first part of the occupation in an unenviable position. As a senior member of the Education Department he was appointed by the Japanese senior assistant to the Director of Religion and Education, a position which he filled with great tact, and by the wisdom and discretion with which he presented the needs of the Churches he was able to do valuable work.

The Rev. P. S. Baboo, at Christ Church Indian Church, faced with a badly damaged building, raised the necessary funds for its repair, and in spite of the great difficulties of transport his congregation carried on loyally. The Rev. Yip Cho Sang, as always indomitably cheerful, was a wise and loving father to his "family" at St. Matthew's Cantonese Church, while at Holy Trinity the Rev. John Lee, assisted by the Rev. Ng Ho Le, maintained and extended the Church's work. He and his congregation even succeeded in paying off the outstanding debt on the Holy Trinity building fund. At the Mission Hall in Jalan Besar the Rev. Gwok Koh Muo, who was ordained priest on March 28th, 1943, the day before we were interned, showed himself to be a fearless and courageous evangelist. At St. Paul's K. T. Ooi, a Singapore lawyer, gave invaluable help as lay reader and also as choirmaster of the Cathedral. I myself owe a special debt of gratitude to the Rev. John Handy. Before the war "J.T.N.", the son of an Anglican priest, had held an important position in the Labour Office. In the middle of 1942 he was licensed as a diocesan lay reader, and gave me, by his affection and counsel, the very greatest assistance at St. Hilda's. He had decided to return to India after the war for testing and training, to be followed by ordination. As soon as it was known that we were to be interned the Bishop asked him if he would agree to be ordained at once. He consented, and was ordained deacon and priest on the day before we were interned. He continued at St. Hilda's and we were overjoyed to find how successful he had been when we returned to Singapore. His lack of experience was more [17/18] than atoned for by his own natural goodness, his simple piety, his uncompromising moral strength and his very deep sense of pastoral obligation.

It is a deep-felt joy to be able to record the gratitude and admiration of the whole Church to these men and to the laity of the Church in Malaya. Of the latter in Singapore I would mention particularly K. T. Alexander, the Bishop's Indian secretary, Miss Poh Chin, and Miss Myrtle Wilkins, who proved themselves hard-working and devoted evangelists, Dong Chui Seng, who kept alive the spirit of St. Andrew's School, George Daniel and Cecil Kaan, who were largely responsible for the high standard of the United Choir of between 70 and 100 voices--one of many joint activities by the Churches of different denominations. They--the clergy and many other men and women--worked together to compile a story of high quality.

IV. INTERNMENT AND THE "DOUBLE TENTH." On March 29th, 1943, the Bishop, Adams and I were interned in Changi prison, a big reinforced concrete building designed to hold some 600 Asiatic prisoners. At this time there were over 3000 there, the majority of whom had already been in the jail for about a year. In some ways it came as a relief to us. In spite of the many and great kindnesses which had been shown us, we had for several months been living on a "knife-edge" of uncertainty. The Gestapo were everywhere, every word and action had to be guarded, we knew that we were being watched and that, on several occasions, strong pressure was being brought to bear to get us interned. Not the least of our anxieties was the possibility of danger to our friends. Several people who came frequently to the house were, in fact, being watched by the police. When the end came we were given 48 hours to make the necessary arrangements, and I shall not easily forget that last week-end. It must have been galling indeed to the Japanese to see the concern of so many of our friends.

[19] At the time of our arrival in Changi jail there were already six clergy there--the Archdeacon, the Ven. Graham White, G. B. Thompson, Colin King, Jack Bennitt, and in addition Bernard Eales and Eric Scott, who had been brought down from up-country. In the women's camp were Mrs. Graham White, Miss Foss of Pudu School, Kuala Lumpur, Dr. Patricia Elliott and Muriel Clark of St. Andrew's Mission Hospital, Beatrice Sherman, formerly of St. Nicholas' Home, Penang, and Mrs. Loveridge, once a member of the Mission, who had given invaluable help with the children of the Orthopaedic Hospital during the war. Throughout the whole three and a-half years of internment, Dr. Elliott, in spite of her age and frailty, worked as one of the doctors in the women's camp. Nothing seemed able to daunt her courage and cheerfulness.

The Rev. R. C. Moore was on leave in Australia. The Rev. R. J. Thompson was for the greater part of the occupation a P.O.W. in Siam, as Chaplain to the Penang Volunteers. The Rev. L. St. G. Petter, Chaplain to the Malacca Volunteers, died in England early in 1946. He spent most of the time in a P.O.W. hospital, but came through remarkably well. The Rev. G. S. Clarke was evacuated from Malaya with the R.A.F. He had joined up as a Chaplain shortly before the surrender. The Rev. C. G. Eagling was interned by the Siamese in Bangkok, where he was able to hold services in the camp and to have occasional contacts with those who were responsible for maintaining Christian worship in the town.

Several of the women missionaries left only a few days before the surrender, amongst them Evelyn Simmonds and Olga Sprenger, of whom nothing has been heard since they left Singapore. Many women and children were killed in the bombing and shelling of evacuation ships or were drowned, and it is feared that they were amongst them.

Evelyn Parr, although wounded in the arm, managed to reach Sumatra, where she died in an internment camp at the beginning of 1945. Her husband, the Rev. Cecil Parr, formerly senior assistant master at St. Andrew's School, died in 1943 as a P.O.W. in Siam, where he was one of the Chaplains with the men on the Bangkok Moulmein railway. After the Japanese surrender I met people who had been with both of them. She had had illness after illness at a [19/20] time when conditions were very bad in the Sumatra camps, until her strength finally gave out, while he impressed all those who knew him by his cheerfulness and endurance.

The Rev. Victor Wardle, of the Missions to Seamen in Singapore, also died in Sumatra at the beginning of 1945. There will be many who will miss his quiet and gentle courtesy during the years to come.

From March until October, 1943, in spite of the appalling overcrowding, squalor and isolation, life was full of interest at Changi. Food was plentiful and it was possible to occupy one's time fully with lectures, plays, games, concerts, gramophone recitals, reading and endless talk. Then and throughout the whole of internment, Church services were held regularly, with a daily celebration of Holy Communion, and there was close co-operation with the representatives of other Churches--Presbyterian, Methodist, the Brethren and the Salvation Army. The Archdeacon and the Bishop both gave valuable and well attended courses of lectures. Confirmation classes and religious study groups were held regularly. Throughout the whole period of internment there were some 70 adult Confirmations. A group known as the Friends of Reunion met for talks, followed by open and group discussion.

But on October 10th, 1943 (a Chinese festival known as the "Double Tenth"--the tenth of the tenth month--a phrase we also adopted), there came a sudden and violent change. Early in the morning we were assembled in the main yard as for a roll-call. But this was no routine matter. A party of several hundred Japanese soldiers arrived, headed by Gestapo officials, and from then until 9 o'clock in the evening a complete and thorough search was made of the buildings and of all personal belongings. A number of people were taken into Singapore for further questioning, and for several months others were being taken away, sometimes in the middle of the night, until in all 57 internees, including three women, were removed from the camp. It is impossible to describe the atmosphere of tension and suspense with which many of us faced those months. We literally never knew from day to day when our turn might come.

The Bishop was amongst the earliest to go. On arrival at Gestapo headquarters he was faced with a formidable [20/21] charge. They said that he had been, and still was (to use their own words) the "Lawrence of Malaya." They alleged that, while still free in Singapore, he had misused his position to organise a large espionage organisation throughout Malaya. They said that, at the time of the surrender, he had been informed by the Financial Secretary and by the Manager of the Singapore branch of the Hong Kong Bank that large stocks of British currency had been hidden away. This money he used for the paying of agents and financing of espionage generally. He had sent money into the jail to be used for the same purpose and had made arrangements for the money to continue to be sent in after he was interned. He was the head of an organisation which received instructions by short-wave wireless in the jail and they were quite convinced that we had a transmitter, also operated from the camp.

These charges were completely false, but they were built up round two things. The Bishop had secretly sent quite large sums of money into the jail, and the Japanese knew it. They also knew that we had at least one short-wave wireless receiving set in the camp.

When the camp was formed a large number of people took considerable amounts of money into internment with them. One of the first actions taken by the camp committee, composed of men elected by the internees themselves, was to invite loans to a camp fund, repayable after the war. With this money considerable quantities of food and, while they were still obtainable, drugs and medicines, were bought through the Japanese. But the money available proved insufficient for purchases over any length of time, and somehow more money had to be obtained if the camp was to be able to continue to buy the many additions to the diet which were essential, particularly for the sick, the aged and the children.

A message was sent out to the Bishop, who borrowed money from a neutral in Singapore in the name of the Anglican Church, and it was then smuggled into the camp. As long as we were free it was fairly simple to get the money through without the knowledge of the Japanese, although they had imposed an absolute rule against contact between the camp and people in the town.

When we were interned the Bishop arranged with his [21/22] secretary, K. T. Alexander, that on receipt of a message he was to go to "Mr. X" and borrow the necessary money. To get the money into the camp required a good deal of ingenuity and real courage, but it was done. Usually it was the same two people who handled it--Choy Koon Heng and his wife, Elizabeth Choy, both of them completely fearless and utterly selfless. Their story will rank as one of the greatest of the occupation. They used various methods, the principal one through a non-Christian shopkeeper named Ah Tek. Lorries from the camp, driven by internees, called fairly frequently at a neighbouring shop. While the attention of the Japanese guards was distracted a package of money would be passed to the driver who brought it back into the camp.

More than once one of the clergy returning from taking the funeral of an internee at the cemetery, found in his robe-case what appeared to be a carton of cigarettes, but was, in fact, several thousand dollars in $10 notes, slipped into the case at the request of the Choys by Mr. Bracken, the cemetery superintendent.

But it was Norman Coulson, a municipal engineer left uninterned by the Japanese until the middle of 1943, who was responsible for the greatest ingenuity and daring. He himself started an organisation in Singapore whereby personal wireless messages to P.O.W. and internees were picked up and sent in to the various camps. He sent into Changi tons of equipment obtained without authorisation from municipal stores under Japanese control, and on one occasion he sent a large sum of money into the jail concealed in a length of piping. His achievements are even more remarkable when it is remembered that the Japanese were doing everything in their power to prevent contacts of this sort. He was one of those who were later arrested by the Gestapo and, as a result of the treatment he received at their hands, he died. His body was returned to the camp for burial, and the many hundreds who attended the funeral service were a witness to the incalculable debt owed to him by every member of the camp.

The Bishop was faced with a very ugly situation when he arrived at Gestapo headquarters. Round those two things, the money and the wireless, and their conviction that we had a transmitter, they had built up an elaborate [22/23] espionage plot, which seemed to make sense. To convince the Japanese that they might be mistaken, and that he might be speaking the truth, cost the Bishop three days of ruthless and merciless torture, being beaten for hour after hour, remaining bound in an agonising position, with the hammering of a constantly reiterated, "You are a spy--you are a spy--you are a spy;" and it was another eight and a half months before they were finally satisfied. Ah Tek, Choy Koon Heng, Elizabeth his wife, and Alexander were all arrested. The last two were freed at the same time as the Bishop, but Koon Heng was sentenced to a term of imprisonment and was only released after the arrival of British troops in Singapore. Ah Tek died as a. result of the treatment he received.

This extract from an official report may give some idea of the conditions of life at Gestapo headquarters. "They were crowded, irrespective of race, sex or state of health, in small cells or cages. They were so cramped that they could not lie down in comfort. No bedding or coverings of any kind were provided, and bright lights were kept burning overhead all night. From 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. inmates had to sit up straight on the bare floor with their knees up and were not allowed to relax or put their hands on the floor, or move or talk. Any infractions of this rigid discipline involved a beating. There was one pedestal water-closet in each cell, and the water flushing into the pan provided the only water supply for all purposes, including drinking. Nearly all of the inmates suffered from dysentery. No soap, towel, toilet articles or handkerchiefs were permitted, and inmates had no clothing other than what they were wearing. In these conditions and this atmosphere of terror these men and women waited, sometimes for months, their summons to interrogation, which might come at any hour of the day or night."

But however much they tried, the Japanese could not destroy the spirit of the prisoners. For example, on one occasion when the Bishop was leading the daily P.T. drill he interspersed the Japanese numbers while conducting the familiar arms-bending and stretching, with the Sursum Corda! He himself was considerably helped by another internee, from whom he learnt several thousand lines of Keats. A Chinese, Lam Mau Fatt, was baptised in the [23/24] only water available, while another inmate of the cell kept watch for the sentry. His preparation had been carried on in a subdued whisper.

On another occasion, while a Roman Catholic girl kept watch, the Bishop held a Communion service in the cell, using grains of burnt rice. Elizabeth Choy, who was sweeping the corridor, knelt down and received her communion through the bars of the cage.

The Bishop returned to the camp in May, 1944, by which time we had moved to a more open site at Sime Road. He had lost four stone in weight and it was many months before he was fit. But his recovery was complete. On our release in September, 1945, he was able to do a month of what he described as the hardest work of his life.

For the remainder of the internment at Sime Road, camp conditions, which had been bad since the "Double Tenth," continued to deteriorate. Food became hopelessly inadequate, but as we became hungrier and more undernourished, more work was expected of us. The camp gardens were our only source of vegetables and gave the sole addition in our daily diet to the small amount of rice allowed us by the Japanese. As time went on an increasing number of people were taken off the gardens and put on to military work, digging large tunnels inside the camp which, at the opening of the Allied attack, would have been used by the Japanese forces. But in spite of malnutrition, malaria and dysentery, the number of deaths was never as high as might have been expected. That this was so was largely due to the work of the doctors, nurses and orderlies, who worked magnificently in the hospitals of both the men's and women's camps.

But amongst those who died were Archdeacon Graham White and his wife, at the beginning of 1945--she in January, he in May. There were many who thought that they should have left Singapore before the surrender, but although they lost their lives by staying, they both achieved a very great deal. He had been for a year the senior priest in internment, and the work he did in keeping people's spirits up and in strengthening their faith, was of the very highest importance and laid the foundations of the camp's religious life. Mrs. Graham White was unwell at intervals throughout the whole of internment, but no matter how [24/25] ill she was feeling, those who went to her with their troubles always found a wise and loving friend.

It was sad that they could not share the glorious welcome given to us at the end of internment by those whom they had served so faithfully for many years. Long before the British troops arrived in Singapore swarms of people invaded the camp, hunting for friends and former employers, bringing presents of food, money and clothes.

So we had come full-circle. Our internment meant sadness and the interruption of many things. But here, in an atmosphere of almost overwhelming joy, was a symbol of the old mutual trust and affection between us and those whom we had tried to serve. Those of us who came through, feel--as I hope may have been shown here--a deep and lasting debt to the Christian people of Malaya.

V. TRIALS AND FREEDOM. Although the formal surrender was signed on August 14th, and visitors began pouring into the camp a few days afterwards, the main body of the British troops did not arrive in Singapore until the beginning of September. In the interval there was a good deal of disturbance in the town, and we were not allowed to leave the camp until September 8th, when I went with the Bishop to take part in the first broadcast to be given from a free Singapore. On the following day we were able to attend services in the town and spent our first night of freedom at Cathedral House.

The welcome given to all of us from the camp by the local people, keyed up as we all were, they and us, by the relief of knowing that the past three and a-half years could be blotted out, was stupendous. On September 6th the Rev. A. J. Bennitt and Bernard Eales had to go into town on a lorry. Bennitt writes of that trip: "First we went to Holy Trinity, where there were a good many people and tremendous excitement when we arrived. Everything in the building was in excellent order. In my desk were all my papers exactly as if I had left them only the day [25/26] before. More people arrived, and we were firmly prevented from going as lunch had been ordered from a neighbouring coffee shop. When it was over we drove on into town, the lorry bedecked with flags, through streets lined deep on one side with cheering crowds. At the Cathedral we met more friends; everyone very friendly, and there was enormous enthusiasm."

Typical of the kindness with which we were surrounded was Bennitt's experience when three Chinese friends asked him for a list of things he would like when he came out of internment. The same evening he was offered three houses and a car--he used the car for four months, and before he left in December had driven hundreds of miles all over Malaya.

Within a few days of the arrival of British troops the Bishop, with three of the clergy and workers who were expecting to remain in Malaya for a short time, moved to Cathedral House to comfort, good food, almost overwhelming friendliness and, at last, privacy! But gradually we learnt something of the cost to the people of Malaya of these years of Japanese occupation. At the beginning of 1942, soon after the fall of Singapore, the Chinese population had suffered cruelly. Amongst the thousands of people throughout the whole peninsula who disappeared and must be presumed to have been murdered, were many Christians: Mr. Chan, one of the staff at St. Andrew's school, several of the boys themselves, Guok Bin Chye, son of the Hinghwa priest, and many more, amongst them some of the best of our younger Churchmen.

Shortly after our internment in March, 1943, the clergy and leading laity,. because of their close association with the Bishop, were the objects of a good deal of suspicion by the military police. The Rev. John Lee, although he was never arrested, was described in his police dossier as "leader of the guerillas in the Yong Peng area of Johore." In March, 1944, five of his leading Church members, including two lay readers and the priest's warden, were arrested. After physical and mental torture three were released on Easter Sunday and the other two a fortnight later.

Face slapping and threats of arrest by irresponsible Japanese were commonplace. The Rev. Huang Yau Ying, [26/27] of Malacca, writes in his report: "In 1944, one week after Easter, I visited Batu Pahat, Ayer Hitam and Yong Peng to conduct services and baptise children and adults. On my return journey, as I was passing Ayer Hitam, my baggage was examined by a sentry, and a Malay inspector of police asked me why I should go to Yong Peng to conduct Christian services when none were allowed. I showed him a testimony and passport in Japanese, but he said that he did not care for them since he could not read them, and he said that I was a Communist. I was slapped and nearly arrested by him at that time."

During his tour of Malaya the Rev. A. J. Bennitt went to Yong Peng, where he heard that at the beginning of 1944 an attack had been made on the village by Malays armed, incited and led (probably driven) by the Japanese, as a reprisal, because the village was the centre of guerillas. About two thousand men, women and children, including many Christian families, were slaughtered. Although the Church was undamaged all the houses on one side of the village street had been burnt.

The damage to Church property was not, on the whole, as serious as it might have been. But few churches escaped completely the outbreak of looting which occurred in each place during the Allied withdrawal and before the arrival of Japanese troops. Only St. George's, Penang, was completely destroyed, although some of the furnishings were saved and put into the Chinese Mission Hall. In 1945 B29s completed the destruction begun by Japanese bombers in 1941.

St. John's, Ipoh, since the arrival of British troops, has been in use as a church again, after the Japanese had turned it into a sauce factory. The Chinese church at Tasek, too, had been completely looted.

But the damage to school property, although the buildings still stand, has been considerable. In many cases all books and furniture have been destroyed. At St. Andrew's school, for example, absolutely nothing was left except the bare bones of the building itself. It was picked clean by looters at the fall of Singapore. Even the grand piano was removed on a bullock cart!

But there is much to put on the credit side. The Church in Malaya has gained in stature and has within it the seeds [27/28] of even further growth as a result of the sufferings of the past four years. Some of the gains have been indicated already in an earlier chapter, particularly as affecting the Church in Singapore. But elsewhere in Malaya there is the same story to be told. The difficulties were enormousopposition in some cases and suspicion everywhere. The leaders of the Church from March 29th, 1943, when the Bishop was interned, were without his guidance at a time when things were becoming increasingly difficult; and yet they proved true leaders and shepherds of their people.

Another outcome of this experience has been a closer understanding between the Christians of different racial groups. In a country like Malaya, peopled by many races, it is never easy to obtain a sense of unity or fellowship. Before the war, Europeans, Indians and Chinese Christians tended to be too sectional in their outlook. But during the Japanese occupation much of that has been broken down. For instance, the Rev. Huang Tung Hsi, of Penang, reports that as a result of the destruction of St. George's, the Chinese Mission Hall, "a more than eighty year-old Malay house has become a central, suitable and cheerful place of worship" for all three congregations, English-speaking, Chinese and Indian. His report goes on to give an account of a service held on Easter Day, 1943, in which all three congregations joined. He says: "I conducted Matins, the Rev. S. Charles celebrated the Holy Communion. The Epistle was read in three languages--Tamil (Indian) by Dr. Muttu; English by Mr. Lunberg; and Chinese by Mr. Ooi Kim Pong. We had a gathering of 481 people and 288 communicants. It was so nice and wonderful to hear their voices in the singing of the hymns, etc., in different languages in the same tune."

The Indian priest in Penang, the Rev. S. Charles, died in August, 1945, since when Huang has taken over all the Indian in addition to his own Chinese work. The same wider unity was shown in Kuala Lumpur, where a Chinese lady made herself responsible' for the greater part of the upkeep of the Indian priest, the Rev. T. Yesadian.

In Malacca the Chinese priest expressly singles out three people who gave him great help when he was ill. All three were Indians.

[29] Yet another difficulty which faced the Church was that of transport and of a continually shifting population. Part of the Japanese policy was to move people from the large towns into agricultural settlements (where large numbers, including the French Roman Catholic Bishop, died from malaria, dysentery and other diseases). Inevitably church attendance figures went down, yet they not only continued to support their priests and other church workers, but in Singapore and Penang paid off debts of $7000 and $3000 respectively on church property. Admittedly inflation made this easier for them, but a substantial part of the debt on Holy Trinity was paid off before the dollar had depreciated to any marked extent.

Not only was each congregation self-supporting--and they are determined now that the war is over to try to continue to be so--but large amounts were being subscribed for the relief and assistance of the poorer members of each congregation.

Soon after the surrender the Rev. Eric Scott flew to Penang, the Rev. Jack Bennitt and the Rev. Bernard Eales went to Kuala Lumpur and Malacca by car (the first civilians to make the journey out of convoy), while the Bishop and I remained in Singapore. The chief job with which we were concerned in all the main centres of Malaya was the organisation of immediate relief in cases of real suffering and hardship, of which there were, unfortunately, a very large number.

But it soon became obvious that much more than this was required. The Military Government set up a Malayan Welfare Council, of which the Bishop was chairman, its members representing all the communities of Malaya--men who were in touch with local opinion and needs, whose function was to plan on a wider basis, looking to the future. It covered an enormous field, and in those first weeks of hasty improvisation the Council was able at least to show the way to an orderly solution of a situation which seemed, at times, to be becoming chaotic.

Meanwhile the reorganising of the Church's work went steadily on. Services chaplains everywhere regarded the needs of the people amongst whom they and their units were stationed as a first claim upon them, and they did all in their power to assist the Asiatic clergy. For example, [29/30] while the Bishop was on leave the Rev. Kenneth Punton, Senior Chaplain to the Forces, acted as his commissary in the diocese, and an R.A.F. Chaplain was acting for some time as priest-in-charge of St. Hilda's, Katong. The Rev. David Rosenthal flew up from New Zealand to take charge of the Cathedral, and the Rev. R. C. Moore returned by air to Kuala Lumpur from Australia. Schools were reopened within a month of the arrival of Allied troops, although without books and, in many cases, without furniture. The two big girls' schools in Kuala Lumpur, St. Mary's and Pudu, both started up again, although the buildings of the latter were unusable, having been stripped of window-frames and all electric and sanitary fittings. In both cases former teachers were ready to start work at once; and without the European headmistress, without proper school furnishings, with very few text-books and exercise books, these Eurasian, Chinese and Indian teachers did magnificent work getting the schools going again. The girls at Pudu school were meeting in the afternoon at another school, but they started at once to collect funds on their own initiative to help furnish their own school when they get it back.

At Yuk San Chinese-speaking school, also in Kuala Lumpur, Peter Lee, a young man who had never before held a responsible position, opened the school with 18o children--many more than before the war. St. Mark's, Butterworth, and in Singapore St. Andrew's, St. Hilda's girls' school and the C.E.Z.M. school all reopened immediately. No-one who was there is likely to forget the morning when St. Andrew's reopened--800 boys, many of whom had been there before the war, gathered in the school hall, starting over again in an attempt to make up a little of what the years have taken fromthem.

At a service in Penang on Easter Day, 1944, 700 people of all denominations crowded into and around the Mission Hall. Commenting on this the Rev. A. J. Bennitt writes: "How this was done I don't know. I should have said that the maximum number that could have squeezed into the hall was 200. But perhaps this is a kind of parable of the Church if it is alive, as I believe it most certainly is, from what I have seen of it in Malaya. More people come crowding in than we had thought possible or provided [30/31] room for. Let us pray that our hopes may be big enough, our faith deep enough, our vision clear enough, our courage great enough to take the opportunity God offers us. Behold I have set before thee an open door, and no man can shut it; for thou hast a little strength, and hast kept My word and hast not denied My name.' "

VI. "FOR YOUR TO-MORROW." And now inevitably and forcibly our minds are turned to the Malaya of the post-war world.

The war-years in Malaya have not been without their lessons, both for the Church and for the individual members of it. The life of the Church during the period of the Japanese occupation has demonstrated one fact very clearly. The rank and file of the Anglican Church did come, in some measure, to a sense of community. The bonds joining a man to his Church and to his fellow members in it were strengthened and tested as they had not been before. There were also many--Chinese, Indians and Eurasians alike--who, with the internment of most of the Europeans, found themselves with new and heavy responsibilities, and the people of the country, both clergy and laity, have shown beyond any doubt the major part which they are able and have a right to play in the life of the Church in Malaya.

There are many who, for the first time, have had an opportunity of testing for themselves and in their own lives the Christian faith which they profess. There are many who would testify to the inestimable value of being able to feel the ground firm under their feet when the world, as a whole, and their own world in particular, appeared to have lost all stability and balance. The foundations of financial security and care-free content upon which their lives had been built, were destroyed by stark reality, by the nightmare of suspicion and dread which were day by day accompaniments of life in "Greater East Asia." The old standards of life and the old touchstones of happiness had become obsolete.

[32] It would be a mistake to exaggerate the position. Christians in Malaya are no different from Christians in Manchester, Manitoba or Madrid--among them can be found both good and bad, ardent and apathetic, selfless and selfish, and by no means all found that their faith was strong enough to stand the strain put upon it. But some there were who, by their courage and initiative, their moral balance at a time when personal values were crashing, their willingness to be of service to their fellows, showed the value for them of a faith which had within it, at its very heart, not only a Cross, but a Hope which carries men through and beyond the Calvaries of life and which can transcend anxiety, pain and suffering.

This core of men and women within the Christian Church who have tested for themselves the real truth of Christian belief and Christian living should, and it is hoped will, provide a far higher proportion of the leaders of the Church than it has ever done before. In the past too little place has been found for the people of the country amongst the leaders of the Church as a whole and in the various centres of Church life.

The Church in Malaya (and here I mean the members of all Christian bodies of whatever denomination) has a great deal to give to the political and social life of the country. World trends are making it increasingly important that the Christian values of justice, honesty, equality of opportunity and full consideration for the rights of the individual should have their proper place in the lives of communities and nations, and individual dedicated Christians have a vital part to play in ensuring that these values are preserved. The first and greatest need, then, is to build up a nucleus of really well-informed, thoughtful Christians who have a vision of Christian faith and life as touching every part of the life of man--personal, family, social, political and economic,--men who can play their full part in planning for the future and in carrying out those plans.

Throughout its history the Church has always been intimately associated with the relief of suffering and schemes for the welfare of mankind. The Japanese, during the occupation of Malaya, used the Christian organisations for the vast amount of relief work which had to be done [32/33] and which, it is safe to say, would not have been done without the Churches and other non-Christian bodies. The British Military Administration, immediately after the relief of Malaya in September, 1945, tackled the problem of emergency relief, but it was to a very large measure left to the Churches to provide the leadership which guided and directed the work and gave it much of its impetus.

But in addition to remedial work as a part of social reconstruction, prevention is of the very highest importance, and within a month of the Allied occupation of Malaya a Welfare Council was formed, composed of the leaders of all the communities with the Bishop of Singapore as Chairman. Covering, as it does, the whole of Malaya, and having a very wide range of interests, dealing for example with education, medical work, rehabilitation and many other problems of first importance, its work should be of the greatest concern to the Church and its members throughout the whole country.

But the Church, while bound to assist the civil arm in providing a world "fit for heroes," has also the task of leading men to an understanding of heroic living and showing them a way of life based upon God and faith in Him. Without the second the achievement of the first becomes impossible. It is here that the Bishop is faced with a big problem in the re-staffing of the diocese. Of the 14 European clergy who were in the diocese in August 1941, three resigned before the outbreak of the war, one who has been interned will not be returning to the diocese on personal grounds, another will be retiring; two, the Rev. A. C. Parr and the Ven. Graham White, died during imprisonment, and the return of three others who were prisoners of war or internees will depend upon the doctor's reports and the future state of their health.

The Indian and Chinese clergy and catechists have done very fine work during the Japanese occupation, but one of their number, the Rev. S. Charles, died shortly before the Japanese surrender, and there are several who are due to retire. In the past practically all the clergy for vernacular work in the diocese have been recruited from outside Malaya, and this policy will have to continue for some time, at any rate. But the Church in Malaya has the power within it to provide its own priests, and there are indications [33/34] of at least a start being made. In the not too distant future it is hoped that the number of men presenting themselves for Orders may make it possible for them to be trained in Malaya.

During the Japanese occupation, education came to a standstill, and the Church's contact with a large number of young students was brought to an end with the closing of the Mission schools. Here again is a problem which must be faced. As has been mentioned, schools re-opened within a few days of the re-occupation, many of them without furniture of any kind and all of them without books, but in all the Anglican schools it was impossible to accept a very large number of those who applied for admission. The problem of education, quite apart from the break for so many in their Christian training, becomes more acute when it is remembered that, apart from a little instruction in the Japanese language, very large numbers of boys and girls have had no instruction of any kind during the years of occupation. Everything possible will have to be done to help then to recover what they have lost. On every consideration, education in all its branches will have a large part in the Government's plans for the coming years, and the Church, which already has done much through its schools, will have opportunities of still greater service. The opening of new schools in centres where there has either never been a Christian school or where, for one reason or another, they have been closed, will need to be carefully considered.

But the work which the Christian Church should be doing amongst the youth of Malaya cannot be limited to the schools alone. Vast numbers of young people are as yet completely out of touch with Christian teaching, and much needs to be done for them, particularly amongst the poorer elements of the country. In addition there is a pressing need for hostels for Christian students at Raffles College and the Medical College, where they would be able to live and where they would come under Christian influences. Many students and young probationer nurses come to Singapore from considerable distances: there has been for many years a steady flow of young people from Borneo, who come to Singapore to complete their training, and it is imperative that they should see and feel the Church of which they are members, caring for and taking an interest in them.

[35] Malaya has been fortunate in having exceptionally fine medical and health services run by the Government, and it is safe to say that every effort will be made to continue and improve upon this tradition. But in the past there has been so much to be done that it was left to non-Government organisations to attempt to fill some of the gaps. The Anglican Church was responsible for St. Nicholas Home for the blind at Penang and St. Andrew's Orthopaedic Hospital in Singapore, both playing a valuable part in the life of the community. But in both places no more than the fringe of the problem was being touched, and both are capable of endless development. The problem of tuberculosis, which has become even more grave as a result of the malnutrition, over-crowding and bad living and working conditions of the past few years, is one in which the Anglican Church might well give its assistance.

But the Church can never be satisfied with purely remedial work. Education, both in the prevention of disease and of elementary hygiene, and also in Christian living and self-dedication, are essential parts of its work. A great deal might be done through the use of trained evangelist health visitors, and it is possible that the resources which were set free through the closing of St. Andrew's Hospital shortly before the outbreak of war may he used to open up some such work as this.

But there still remains the greatest task of all--to demonstrate, to the many thousands who do not walk in the light of the love of God, the truth of the Gospel, both in the corporate life of the Church, with its ministry of the word and sacraments, and also through the dedicated lives of individual Christians. The participation of the Church in solving the many problems outlined above will in itself be of the highest usefulness in witnessing to the Christian faith, but nothing can take the place of direct evangelism. "The people that walk in darkness" number hundreds of thousands. They are of all races--Chinese, European, Indian, Eurasian and Malay--and of many tongues, and there is much to be done. The Malays, who form about two-fifths of the total population of Malaya, in many cases educated, able and cultured, are all Muslims and have scarcely been touched by Christian teaching. [35/36] The Church will have to consider very seriously during the years ahead what attitude it is to adopt towards the whole question of evangelistic work among the Malays.

On this point, on evangelism generally and in many other matters of common interest, it is of the highest importance that the Churches of different denominations should arrive at a close understanding and a high degree of co-operation. Some sort of common front is essential unless the witness of the "Christian Community" is to be hopelessly impaired. The foundations have already been laid with the formation of the Christian Federation of the Churches in 1942. It would seem desirable that in every centre a Christian council should be formed, composed of representatives of all the Christian bodies who would act as the spokesmen of the Church and give expression to Christian opinion in each place, and themselves implement relief and welfare schemes.

As will readily be seen, the problems facing the Church in Malaya--and only a few of them are enumerated here are great. At a thanksgiving service in the Cathedral shortly after the entry of the British troops into Singapore, the Bishop spoke in these words of the spirit in which those problems should be faced. "St. Paul would have us show our strength by bearing the infirmities of the weak, in making other people's trials our own. We shall not help others to advance until we have taken our stand with them and made their tasks our tasks. We know that well in the realm of education. The man of learning who is so engrossed in his own brilliancy and so anxious to make his standpoint clear that he forgets or fails to enter into the mind of his hearers, may impress them, but he will not educate them, and the most brilliant gifts of administration are exercised by those who have a humble and lowly heart and can enter into sympathy, into deep understanding with those whom they are trying to govern." Those words were addressed primarily to representatives of the Military Administration in Malaya, but they also express the underlying spirit in which the Church in Malaya should step forward into the future.