|

|

The author of the following brief notices of Lewchew or Loo Choo, now discharges a debt due to the friends and supporters of the Lewchew Naval Mission, in giving them an authenticated narrative of his visit to that country. The delay has arisen from a sense of delicacy and unwillingness to give his views to the public before the British government had taken its own independent course on the question of a British subject remaining at Lewchew.

The Foreign Secretary of State has, in the name of the Queen of Great Britain, thrown the shield of British protection around the missionary, Dr. Bettelheim; and the naval commander, Captain Shadwell, R.N., who, in the beginning of the present year, was despatched to convey these renewed communications to the Lewchewan authorities, has brought back a report which shows that the position of the missionary, and the general prospects of the mission, have been improved since the author's visit in October, 1850.

Under such circumstances--the political and international question having been now disposed of by those to whose peculiar province it belonged--the author felt that, as the representative of the Church of England, and a pioneer of British Christianity in these dark regions of the farthest East, he would fail to obey a clear call of divine Providence, if he refrained longer from laying before the friends of missions at home, a brief statement of the present condition and prospects of the Lew-chewan Mission.

Seven years ago a few naval officers formed themselves into a society, sent out a missionary labourer, and have hitherto persevered against multiplied difficulties and discouragements, sufficient to have overpowered minds less hopeful and less sustained by faith in the sure fulfillment of God's promises in the extension of the Redeemer's kingdom.

Their missionary--a converted Jew--possesses many qualifications for his work; he is an able linguist--has gained a medical diploma in a foreign university--possesses great energy of mind, and activity of body--is indefatigable in his labours--and has braved many trials, and surmounted much opposition, cheered by the one hope of being permitted to diffuse the gospel in Lew-chew, and, through Lewchew, to the secluded and benighted empire of Japan.

The author would bespeak from the reader an indulgent consideration even towards the peculiar views or course of action which may on any point be observable in this descendant of Abraham, now our brother in Christ. If in his public communications he has sometimes uttered sentiments which savour more of a Joshua than of a Paul, let it be remembered also, that a man of less fortitude, of gentler texture, and of less sanguine temperament, would probably have sunk into an early grave, or prematurely abandoned his attempt.

Prompt, stern, and uncompromising in the vindication of his supposed rights as a British subject, he is, at the same time, not a stranger to the tenderest emotions and holiest affections, which dignify, ennoble, and adorn a Christian soul. Let those who, in comparative comfort and luxury, have to suffer little for the cause of Christ, learn to hope favourably and to contribute cheerfully on behalf of those who "have hazarded their lives for the name of our Lord Jesus Christ."

At the present time Lewchew is the only avenue to Japan, the nearest part of which is only three hundred miles to the north-east. A mission to the former is in effect a mission prospectively to the latter country also. Present appearances indicate a probability that an unwonted effort will be made ere long by the United States to open Japan to foreign commerce. In such an event, a mission establishment at Lewchew would at once supply a body of linguists, already prepared and ready to enter upon this last remaining of the countries of the East at present debarred from intercourse with Christendom.

Two Roman Catholic missionaries settled for a time in Lewchew, but ultimately abandoned their mission in despair of success, while our Protestant missionary persevered and remained. One of them, M. Forcade, has since become titular bishop of Samos and vicar-general of Japan; and has, a few months since, returned to Europe on account of the present hopelessness of effecting an entrance into Japan.

The importance of retaining the vantage-ground already acquired at Lewchew, is thus doubly apparent from the past efforts of the Church of Rome; and our admiration of the persevering zeal which has enabled our Protestant brother to abide at his post, is proportionably increased.

He has recently written an account of a Lewchewan, named Satchi Hama, whom he believes to have become a true convert to the Gospel, and to have suffered secret martyrdom through his constancy unto death. He also writes his assured conviction of the friendliness towards the foreigner and favourableness to the Christian religion, which prevail in the minds of the bulk of the population, and are restrained only by the fear of persecution by the Lewchewan government. Concerning the correctness of these views the author is unwilling and unable to pronounce any certain opinion.

On the Lewchewan Naval Mission Committee, and, through them, on the friends of Christian missions to the heathen, will now devolve the question to decide, whether the present advantages are worth being prosecuted and retained, or whether, after six years' toil and danger, their missionary shall be recalled, and the work be given up.

If they decide on pursuing the good work already begun, the mission should be extended forthwith by the addition of two devoted and discreet clergymen; and thus a security be afforded for enlarged success by that salutary admixture of individual judgments, temperaments, and talents which an increased number of labourers can alone supply.

The work of Captain Basil Hall, which first excited an interest in Lewchew, will also have prepared the way for the details now laid before the reader.

The author expresses his earnest prayer that the following pages, written in haste, after intervals of time, and amid opportunities snatched from other manifold engagements, may be a means, under God, of exciting a deeper interest in the spread of the Gospel in these regions of the far East.

St. Paul's College, Victoria, Hong Kong,

July, 1852.

On Monday, September 23rd, 1850, I embarked at Hong Kong, in H.M. steam-sloop, the Reynard, which had been placed under orders by the naval commander-in-chief on the station, to convey me, on my first episcopal visitation, to the consular cities in the northern ports of China. A correspondence having arisen between H. M. Principal Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and the British plenipotentiary in China, respecting the position of an English missionary, for some years stationed at Lewchew, and the treatment of the latter by the native authorities of that island, it was arranged that the Reynard should touch at Lewchew on her voyage northward to Shanghae.

For three days we alternately steamed and sailed under canvass, until, when about twenty-five miles off Amoy, finding that the N.E. monsoon had set in, we changed our course to the S.E., in order to avoid a probably rough and tedious passage up the Formosa channel. On the fourth day we had doubled the southern end of Formosa, and continued to beat up against a head-wind, favoured by a current, along the eastern coast of the island, at times being sufficiently near the shore to descry the huts of the natives and the beautiful foliage which clothes the mountain sides.

The wind changing to a fresh N.W. breeze, enabled us to run on in a direct course, and on October 3rd, we came in sight of the great Lewchew Island. A long chain of low coral islands stretches about twenty miles outside, and guards the approach from the south-west. We pursued our intricate course under steam, through the numerous islets and coral reefs, and came to anchor in the outer harbour of Napa, situated on the south-west extremity of the island.

On a little headland, overhanging the sea, and near to a building which had the appearance of a temple, a British union-jack suddenly made its appearance, suspended from a slender flag-staff, and reversed. Soon after we perceived on the same spot, about a mile distant from our anchorage, the waving of handkerchiefs from a European lady and children, who were soon after joined by a male European, whom we correctly conjectured to be Dr. Bettelheim and his family. The anxiety of the family appeared great to arrest our attention, till the discharge of a gun, the whistle of the steamer, and the noise of dropping the anchor, seemed to re-assure their minds that they were observed by us. On either side of this headland was a circular bay, about a mile in depth, the intervening land forming the site of the town of Napa.

A number of little boats were in sight, none of which durst approach us, and during the two hours of remaining day-light no communication took place between the ship and the people on shore. The shore appeared generally flat, with undulating hills towards the interior, with vegetation and foliage much resembling that of an English landscape. On all the little eminences, and especially on one conspicuous spot, which formed one vast grave-yard, crowds of people were collected together to witness the novel wonder of a vessel propelled by steam.

Soon after sunrise the next morning, Captain Cracroft, B.N., and myself, proceeded in a boat to the southern harbour. The Japanese trading junks had left Lewchew a few weeks before; and at the present time the number of large junks did not exceed thirty or forty. As we passed under the native craft, and were approaching the landing-place, we were met by a host of Lewchewan officers, who accosted us in Chinese terms of politeness, and were on their way to our ship to pay their respects. Seeing that we continued to make for the landing-place, they turned back and followed us. On our landing, we were met by Dr. and Mrs. Bettelheim, and by a crowd of subordinate government officers, attendants, and people.

After we had received the hearty greetings of the former, we accompanied them to their dwelling; and, leaving our luggage in charge of a number of apparently well-disposed agents of the Lewchewan government, we walked about. a mile through streets of neat dwellings to the isolated promontory on which the missionary family reside. Here, in their little home or prison house, perched on a rocky but salubrious elevation, overhanging the sea, they had for four years and a half borne the privations of exile from intercourse with civilized society.

It may be convenient here to allude briefly to the circumstances under which Dr. Bettelheim had effected his location on the island. A few years ago some naval officers in England formed a society called the "Lewchew Naval Mission," with the object of sending Christian missionaries to Lewchew, which had many years ago been visited by Lieutenant Clifford, one of the leading projectors of the mission. The individual sent out as their first, agent was a physician, a native of Hungary, of a respectable Israelitish family, but a naturalized British subject, and married to an Englishwoman.

After his conversion from Judaism to Christianity, he became known to some influential clergymen in London, by whom he was introduced and recommended to the society above mentioned. He arrived with his wife at Hong Kong in the early part of 1846, and, after a temporary stay there, embarked for Lewchew, where he arrived in the month of May in the same year. It would be apart from my present purpose, and also exceed the limits of this brief narrative, to detail the circumstances of his first landing, the surprise of the natives, and the alarm of the Lewchewan authorities. At first the arts of mild persuasion, afterwards less dubious marks of opposition, and, lastly, a system of open annoyance and intimidation, appear to have been employed to dislodge him from his position.

Letters had been addressed, both by the Lewchewan authorities and by the Chinese imperial commissioners to the British plenipotentiary at Hong Kong, requesting the compulsory removal of the missionary family. The native population, at first friendly and well-disposed, were prevented from visiting the mission dispensary, or holding any intercourse with the foreigners; and such was the universal terror inspired by the emissaries of the government, that the appearance of the missionary was the signal for a general dispersion of the people.

As far as could be ascertained, there appeared to be no hostility towards the Christian religion, nor any jealousy on behalf of their own superstitious usages, which prompted the native authorities to this course of conduct. Political fears were at the bottom of the whole policy. On the one hand, they dreaded the vengeance of their Japanese masters, who would view the residence of a European in Lewchew as the first step towards breaking down the exclusiveness of Japan itself. On the other hand, they had secret fears of the displeasure of the British government at any violence done to a British subject. The visits of one or two British men-of-war on previous occasions had left the Lewchewan government in doubt as to the ultimate intentions of the British, and the exact position of the missionary.

The missionary himself, isolated from the society, the ordinary comforts, and the sympathy of European life, had suffered acutely under the privations and contumely to which he was exposed, and addressed various representations to the British government at home.

The latter had opened a communication with the Lewchewan Naval Mission committee, suggesting that the difficulties in the way of Dr. Bettelheim's continued residence in the island rendered his recall highly desirable.

The committee, in their reply, drew attention to the equally discouraging circumstances under which many a mission had at first been founded in countries which now were reaping the fruits of perseverance in the midst of early difficulties in the conversion of large numbers of the inhabitants to the Christian faith.

The Foreign Secretary of State acknowledged the force of these statements, and expressed the willingness of the British government to protect Dr. Bettelheim as long as it was deemed right for him to remain at his post. In accordance therewith, a recent despatch from Lord Palmerston to the British governor of Hong Kong, conveyed instructions that a man-of-war should occasionally touch at Lewchew, and that the Lewchewan authorities should be informed that the British government took an interest in Dr. Bettelheim, and would view with displeasure any attempt to repel him from Lewchew by a system of annoyance or persecution.

Such were the circumstances under which the Reynard made her sudden appearance in the harbour of Napa.

On our approach to the missionary's residence, we observed various symptoms of the system of secret espionage adopted by the authorities towards him. Near the entrance into the court was a small building composed of mats, and forming a shelter for the police agents who kept watch over his proceedings, and were the medium of his communications with the government.

They acted also as purveyors of provisions, the people being forbidden to sell any article to the foreigners. We passed under an outer gateway with the usual Chinese inscriptions and mottoes. A pair of antithetical sentences on tablets, one on either side, contained also a Chinese adaptation of the texts, "The acceptable year of the Lord is come," and "There is none other name (but Jesus') under heaven given among men whereby we must be saved."

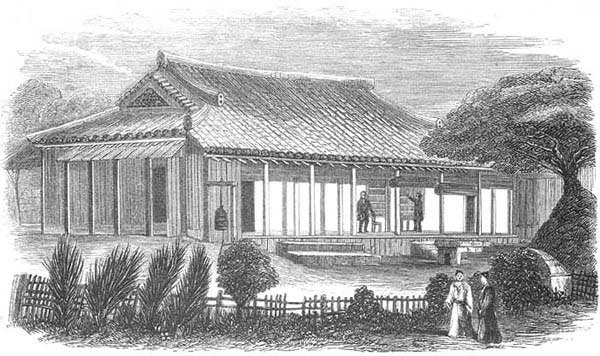

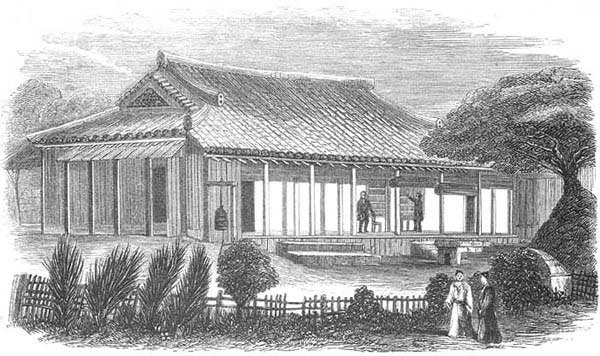

The house itself was previously a Budhist temple. With that religious indifference which is universally prevalent in China, it was ceded by the priests in charge to the foreign family, at the request of the authorities.

A spot better adapted for exclusion from the people, and for the agency of spies, could not have been fixed upon. The house was in almost the same state as before its present appropriation. The images only had been removed; the open halls had slender partitions of boards around the sides; a few paper windows were inserted to shut out the cold of winter, and a portion of the accumulated dirt within had been carried away.

The inscriptions, however, remained on various tablets: and some sacred bells of large size--on which were inscribed in Chinese, the names of the contributors towards their purchase as a gift to the temple--occupied the usual position at the entrance. Behind the house was a little space of ground, about fifty yards in length, bounded by another smaller temple; and outside the whole was a firmly constructed enclosure built of stone, and presenting, from the sea, the appearance of a fortified wall. On either side there was also some uncultivated ground, covered with wild shrubs and plants resembling the cactus and pine apple.

At a little distance inland there were some well cultivated gardens and a few houses. A narrow road surrounded the missionary premises, effectually cutting him off from contact with the natives, and forming a convenient cordon for the government spies.

On our arrival in this temple dwelling, it was deemed expedient that no time should be lost in opening a communication with the native authorities. The native servants, who were appointed by the government, and usually removed or changed every tenth day,--being paid by the government and not by the missionary,--were not likely to regard the latter as their master, or to perform any services beyond what their own inclination or caprice prompted. They were now absent, having, without any previous intimation, taken their departure for a few hours.

Wishing to obtain for Captain Cracroft an official messenger to the authorities, Dr. Bettelheim went to the entrance door of his dwelling, and spoke in a loud voice towards the police shed. Immediately two subordinate officers, dressed out in the usual official costume, and with high yellow hats, made their appearance and commenced their bowings. A Chinese letter, duly sealed, was put into their hands, directed to the authorities, containing the instructions of Lord Palmerston, and requesting an early interview with the principal authority of the island.

The messengers were very inquisitive, and rather unwilling to take their departure for a time, wishing to know the contents, and attempting to render themselves a more prominent and important party in the negotiations. They seemed a very cringing servile class of men, and were evidently alarmed at the determined perseverance to hold no communication except with the highest ruler in their miniature kingdom.

In the meantime the Reynard had got up her steam, and moved to a better anchorage in the northern harbour, nearer the shore, and within sight also of Shui-di, the capital, three or four miles distant. This unintentional coincidence perhaps helped also to secure immediate attention to the despatch. Later in the day a reply came, fixing an interview for the next day at noon with the second official in the island. As it was advisable that no unnecessary delay should take place, it was judged expedient for the present to overlook this slight, and to arrange this preliminary meeting accordingly.

The thermometer was now about 80°, and the heat during the day prevented much walking until towards the evening. About an hour before sunset I accompanied Dr. Bettelheim on a walk through the town. We pursued our course through a number of streets, which generally consisted of neat walls on either side, built of coral fitted compactly together, and apparently without any mortar, presenting a clean and pretty appearance, and forming (as I was informed) a strong contrast with the poverty and filth generally existing within.

These outer walls enclose little courts, which had a few shrubs and flowers, the houses themselves lying a few feet further back from the street. The houses of the poorest classes, and the few shops which we saw were generally without a court, and opened directly upon the thoroughfares. The people generally bowed in return to any advances of civility; and some would even utter a few words of hurried reply to the addresses of Dr. Bettelheim in passing. The higher and more wealthy classes evinced less fear; but it was a rare circumstance to hear a person utter more than ten words, although they were very lavish in their bowings.

They would generally remain for two or three minutes when addressed collectively; but when one individual was selected as the person addressed, there were palpable signs of alarm, and he invariably made a hasty retreat. This odd mixture of outward respect and unwillingness to enter into conversation was the kind of reception universally experienced. But on our arrival at the large public square which formed the market-place, and in which probably two or three thousand Lewchewans were at that time congregated, and eagerly engaged in traffic, one of the most remarkable scenes took place that I ever witnessed.

Here, on a large scale, there was a renewal of what had been previously observable only in detail. On our walking into the square, there was a general dispersion of buyers and sellers, and we were left alone with benches and stalls loaded with provisions for sale, but abandoned by their owners. On our proceeding to the other side of the square, the same signs of a general flight appeared.

A thousand persons, who just before were quietly engaged in buying and selling, retreated in one hurried mass to the opposite quarter; and there, at about fifty yards' distance, they turned round, like a flock of sheep, vacantly staring at us. A few aged women and cripples alone remained, who were unable to escape, and who received our advances towards conversation in mute astonishment and silent terror.

Not a word escaped their lips. Wherever we moved, there seemed to be the same fixed determination to avoid contact; and yet there was not any mark of anger or disrespect. A few of the literary class and government officers, as they passed along, appeared to be less under the influence of fear, and exhibited less equivocal marks of defiance in the sneer which they assumed as they hurried by.

One old Bonze seemed to be placed in great perplexity, in his endeavour to be polite to ourselves and to obey the orders of the government. Dr. Bettelheim addressed a few questions to him, to which he responded with many smiles and low bowings, but yet stammering and confused with embarrassment at the possibility of being observed. Along whole lines of streets leading from the market-square, we perceived the shops shut, and the doors barricaded in anticipation of our arrival; and everything, as if by some mysterious power of magic, suddenly wore the appearance of solitude and desolation.

A few natives running forward gave the signal to clear the way, and every wayfarer coming towards us turned suddenly down some bye-lane, so as to take a circuitous route, and avoid meeting us.

A few natives, to whom such a means of escape was not easily accessible, after apparently making a hasty calculation between the inconvenience of turning back and the danger of being involved in trouble by meeting us, came towards us with hesitating steps, A few words of kindness from Dr. Bettelheim, instead of composing their minds, only increased their alarm; and they pressed their shoulders against the wall in their anxiety to pass us at as great a distance as possible. But not a word of reply could be extorted, and I soon came to the conclusion that it was not the part of kindness to encourage the attempt, and to expose them to the hazard of incurring trouble on our account.

For the first two years after the arrival of the missionary, there were but few difficulties of this kind, and the people could easily be induced to listen to his instructions. Sometimes large crowds of willing and apparently attentive and interested hearers were assembled in the open air. The present demeanour of the people was evidently produced by the government, who adopted this method of convincing the missionary of the hopelessness of his undertaking.

In the earlier stage of the mission, an attempt was made to render the press the means of spreading abroad a knowledge of Christian truth; and it was hoped that tracts left at the doors of the houses, or distributed to such of the natives as could be induced to accept them in secret, might become a substitute for the oral instructions of a living missionary.

But the next morning these were all carefully collected and returned by the police, as if to convey the intimation to the missionary that the isolation and solitude of a leper would henceforward be his lot among them.

We passed several open sheets of water, forming a succession of basins, over the narrower parts of which were some arched bridges of stone. There were to be seen several Budhist temples, in one of which we sat down for some time. There are no Mahomedans, nor any of the Taouist or Rationalistic idolatrous sect of China in the island.

Budhism is the popular superstition, and forms, with the maxims of Confucius, the same kind of compound between political ethics and gross superstition as that which exerts its influence over the popular mind in China. The Bonzes, or Budhist priests, however, do not appear to be held in so great contempt as in China; the cause of which lies probably in the fact that in Lewchew society is generally composed of a lower class of population than in the more wealthy and civilized country of China.

It is a common occurrence for respectable families to dedicate a son to the profession of the priesthood, as one which in no way detracts from their social standing, and is otherwise a measure acceptable to their kinsmen from their hope of inheriting the pecuniary savings of one who, being bound to celibacy, can have no direct heir.

The people in the streets wore a simple robe much resembling in shape that of a Budhist priest in China, being a mere loose flowing gown, with large sleeves, and a fold or collar extending from the neck down either side of the breast. The men have this dress confined by a cotton girdle, and are thus distinguished from the women, who leave their robe unconfined.

The latter have never adopted from China the absurd and cruel custom of crippling their feet. The dress of both sexes is formed of a coarse kind of gray cloth. The common people, when engaged in their labour, approach the nearest to a state of perfect nudity of any nation I ever saw. The common dress of the Malays is many steps of civilization in advance of the Lewchewan labourer. Even a loincloth would be a great improvement on the scanty covering which can be only regarded as an apology for clothing, consisting merely of a rag a few inches square.

They were generally without shoes, and their feet seemed to have attained the hardness of a horse's hoof, if we might judge from the rapidity and ease with which they ran over the hard coral stones of which the roads are formed. Except the magistrates and agents of the government, none of the inhabitants wear any head-dress.

The chief peculiarity in their personal appearance is the mode in which the men bind their hair into a topknot. The crown of the head, to the extent of two or three inches, is shorn and shaven; and into the vacant space the surrounding locks are drawn and plaited into the form of a circular comb.

By means of oil and lampblack mixed together, the hair is well greased till it has acquired the necessary lustre and consistency. Two hair-pins of large size are then passed through, one above the other, extending forward and behind a couple of inches each way, and the fore-end of the lower pin is ornamented with a kind of star.

The rank of a Lewchewan is ascertained by the metal of his hair-pins; the literati and dominant caste wearing ornaments made of silver, or, if unable to afford them of so valuable a material, of lead or pewter. The lower classes have their hair-pins made uniformly of brass, and in this simple difference consists the external distinctions of rank.

The habits of the people are dirty, even dirtier than the lower classes of Chinese. Their features, partaking of a strong Mongolian cast and figure, are very different from the Chinese, and their great resemblance to the Japanese proves that the blood of the latter race predominates in their veins. The women were frequently observed bearing burdens, and not altogether shut out from the view of the other sex. In both sexes there was a remarkable absence of everything associated in a European mind with the idea of beauty.

But we return to the negotiations with the authorities. On Saturday, October 5th, we received an announcement from two subordinate officers that the poo-ching ta-foo, the second official in the island, whose authority extended over the southern portion of Lewchew, was awaiting the appointed interview, and had sent them, with his visiting cards, to pay his respects to us. Captain Cracroft and myself, with eight of the ship's officers in full uniform, walked about a mile to the place where we landed on the preceding day, near to which was the large public office in which the meeting was to be held.

It was for various reasons deemed expedient that Dr. Bettelheim should not accompany us, nor take any part in the negotiations, his own acute sensitiveness to the protracted annoyances which he had received from the government not being likely, in our opinion, to conduce to that calm and moderate adjustment of matters which Captain Cracroft wished to promote. The duties of interpreter consequently devolved on myself, or more properly speaking on my Chinese secretary, Chung-chun-seen-sang; and I was not unwilling to avail myself of an opportunity of using my influence in effecting a good understanding on terms advantageous to the missionary, and by a mode of procedure conciliatory and courteous to the native authorities.

A large crowd was assembled around the entrance, about a hundred officers greeted us in the inner court, two of whom acted as our conductors; one of them also venturing on the peculiarity of shaking hands with us. The poo-ching, with his subordinate the te-fang-quan (the local governor of Napa, and the third officer in the kingdom), received us at the entrance of a little raised room, or platform, to which they conducted us; placing the captain and myself in the seats of honour, with our other companions seated near us, and themselves sitting opposite us.

About twenty native officers stood below the two magistrates; and my Chinese secretary and Chinese servant, together with two English sailors, were the only other persons standing in the room. There was a large screen before a hall in one part of the court as we entered, and many indications of person behind watching with intense curiosity our movements. This might have concealed some fair spectators, excluded by oriental etiquette from a nearer and more familiar view. The suspicion, however, crossed our minds that the tsung-li, the deputy governor-general, or prime minister of the country, was seated within, anxious to obtain the earliest information respecting the interview, but nevertheless desirous of securing a fancied advantage in the popular mind by not condescending to admit the foreign visitors into his presence.

The poo-ching was a poor imbecile-looking old man, who seemed to be under the influence of the te-fang-quan and of another Lewchewan subordinate, whom we judged, from what we saw on this and other occasions, to unite in his person the offices of interpreter, counsellor, spy, and police-inspector; for which functions his astute countenance and plausible bearing seemed abundantly to qualify him. This man seemed to possess ubiquity and an aptitude for work of every kind, as we had frequent opportunities of witnessing during our stay at Lewchew.

Wherever we went, this man's form and features met us in every direction. At one time he would volunteer to attend us in our walks, and, preceding us a little, easily contrived that we should be in no danger from meeting a solitary individual. Sometimes he would fall back to our rear, and, engaging earnestly in conversation with Chung-chun seen-sang, would extract every point of desired information. On the present occasion he was in reality the most important personage, though ostensibly filling a very subordinate post.

He called himself by the Chinese family surname of Chang; nor is it likely that those who bore a part in the transactions of this one week will ever forget the name or the individual. We had now to arrange the medium and order of our oral communications. Captain Cracroft, who on this occasion had conferred on him the title of Envoy, conversed with me in English on the communications which it was deemed desirable to make.

I then spoke the purport of them, partly in Latin and partly in Chinese, to Chung-chun, who, in his turn, reported them in the Peking dialect to Chang. The latter functionary then communicated with the Lewchewan mandarins in their own tongue. All replies came back also by the same circuitous route, so that a great deal of time was expended in effecting a very little amount of inter-communication.

We apologized, in the first instance, for not having done them the honour of bringing a military guard, which we attributed to the rain which had fallen that morning; an omission which they evidently regarded with feelings very different from anything like a sense of discourtesy. Our captain expressed a little disappointment at our fellow-subject not having been permitted to hire any boat, or send any letter to our ship on the day of our arrival, for which they found no difficulty in inventing a ready excuse.

We passed on to the more agreeable duty of thanking them for the present of a bullock, goats, poultry, and vegetables, which had been sent to the ship on the previous day, and for which the captain now proffered payment, which was declined, on the ground of its being a mere ordinary present and mark of courtesy. The captain asked, for himself and his officers, the loan of some horses, for which they were willing to pay a liberal remuneration during their stay.

To this it was replied that horses were very scarce--only the highest civil dignitaries possessed them, and there were only two or three in the whole island.

This was also allowed to pass without any rejoinder, although the French admiral some time previously experienced no difficulty in hiring more than fifty for himself and his party; and it was moreover estimated by one competent to form a correct judgment, that there were at least one thousand horses in Lewchew.

Our walk on that day revealed to us a contradiction of their statement. The officials, however, told the captain that he and his officers were fully at liberty to ramble about the country wherever they pleased on foot.

The usual preparations of a feast in Chinese style were now perceptible, during which many acts of politeness were performed on both sides; and our hosts, the poo-ching and te-fang-quan, were apparently not a little satisfied with the result of the interview, until an observation was made that the main business still remained, to which the captain would soon beg permission to call their attention.

The name of Bettelheim now seemed to raise a train of unpleasant thoughts and reminiscences; and Chang stroked his beard, and drew his breath audibly between his teeth in a way that showed a little anxiety. The unpleasant truth seemed to flash across their minds that Bettelheim was not only a British subject, but that the ship's arrival was in some way connected with their demeanour towards him.

We had also inquired whether a fire-ship, i.e., a vessel propelled by steam, had ever visited Lewchew before; and on their replying in the negative, they were told that possibly hereafter steam ships would not be so rare a spectacle. This was not at all relished by Chang; and on his reporting it to his superiors, they were evidently disconcerted, and expressed their earnest hope that they might not often be favoured with the visit of a steamer--that her arrival would be a misfortune to them, and that the heavy expense of making a present each time was a public calamity.

The captain endeavoured to re-assure their minds, by the statement that British was a friendly power, and that the utmost strictness should be observed in making a liberal payment for all the provisions brought as presents. To this they objected also, saying that their territory was small, the soil was barren, the people were poor, and that there was no medium of currency nor money; and the purchase of commodities was altogether effected by barter and exchange.

Of their own accord they now adverted to the absence of the prime minister, which they excused on the ground of sickness. The captain professed his readiness to wait at Lewchew until his recovery, and volunteered the medical services of the naval surgeon. They replied that his disease was peculiar, and that foreign medicines were of no avail to his disorder.

Of their own accord, also, they drew the conversation to Dr. Bettelheim's residence in Lewchew, and earnestly requested the captain forcibly to compel him to leave their country, and to relieve them of the burden of his support. The instructions of Lord Palmerston were again read to them, and the inability of the captain to use force in carrying away a British subject was explained to them.

They were also expostulated with on the unreasonableness of pursuing a system of annoyance and ill-treatment towards a missionary physician, who came to their country with the disinterested motive of benefiting the people, and was willing to pay its proper value for everything he received from them.

They hereupon, in terms less softened and courteous than those usually employed, inveighed against Dr. Bettelheim as being a liar, if he ever stated to us that he had received any wrong from them.

Finding that our captain did not deem their denial satisfactory, they suddenly adopted a course of proceeding, as distasteful to us as it was degrading to them. The two officials with all their attendants, left their seats, and kneeling down before us, proceeded to make the kotow, or knocking of heads on the ground. It was deemed right to intimate that our captain was only a bearer of instruction, but that he wished to draw attention to a letter of complaints against the Lewchewan rulers, written by Dr. Bettelheim, previously to submitting them to the British government at Hong Kong.

The subjects of complaint were given to them in Chinese writing, as follows:--A bodily assault, and summary removal of the missionary, by six police agents, from a Lewchewan dwelling, in which he was amicably conversing with the proprietor, in prosecution of his missionary work; his exclusion from purchasing provisions from the people; the forcible interruption of him in the midst of a surgical operation for cataract; his being prevented from hiring any natives to help in destroying the snakes which infested his house and court; insults offered by the police to his wife when walking abroad; his stinted dietary and bad provisions; the intimidation practised to prevent his engaging workmen or servants; his exclusion from the public ferry, and inability to hire a conveyance; and, lastly, the system of employing spies to besiege his dwelling, and to track his footsteps whenever he left his house.

Such were the grievances of which Dr. Bettelheim complained; and the removal or alleviation of which the authorities were requested to effect. More pointed allusion was now made to the slight of the prime minister in deputing the poo-ching as his substitute, and we suddenly took our departure, with the intimation that it would be necessary to have an early interview with the chief magistrate himself, as it was only with the highest and most responsible functionary that the captain was willing to negociate in any future discussion of the matter.

As the next day was the Christian sabbath, he requested an interview with the prime minister himself on the day following. Various presents of native manufactures, which were laid at the feet of Captain Cracroft, were declined by him until after the interview should be granted. A boat was afterwards sent to convey these presents to the ship, but the attempt was equally unsuccessful there, and we soon after had an intimation that on the fourth day the prime minister would be sufficiently recovered to come down to Napa from the capital, and to afford us the desired meeting.

Before we separated two petitions, in Chinese, were presented to the captain, one of which referred exclusively to Dr. Bettelheim, and the other was a more general statement of the resources of the island, and its relations to Japan. The latter document appears to be a more explicit and detailed exposition of their political connexion with the latter country, than any which they ever before communicated to a foreign ship visiting the island.

The following is a literal translation of the two petitions. The commencement of the second document appears to refer to myself, as I had then taken up my temporary abode with Dr. Bettelheim, in the temple; and the authorities seemed to be afraid lest I should be left behind as a permanent resident in the island.

"The dutiful petition of Ma-Leang-tsae (and others), the vice-governor-general of Lewchew, entreating his excellency to look down in compassion, and take away Bettelheim and his family to his home, that our little country may be at rest. We lie hid in a corner of the sea; the soil is barren; and the people are destitute. During the period of Bettelheim's residence here, both officers and people have been employed in procuring his supplies, to the neglect of their avocations, and the prejudice of public business.

The upper classes are liable to expenses on account of sacrificial offerings and public granaries; and the common people are at the expense of providing for themselves their daily support, which things greatly impoverish us. If Bettelheim do not soon return to his home, our distress must increase still further, and the country will not be able to stand erect.

"On a previous occasion, in the eleventh month of last year (December, 1849), when the English government sent an envoy hither, we transmitted a special despatch, requesting that Bettelheim might be removed. [Reference is here made to the visit of H.M. brig-of-war, the Pilot.] As yet no answer has come. But as your honourable ship has just arrived, while we are in expectation of the reply, we beg your excellency to receive Bettelheim and his family on board your honourable ship, and take them to their home. Thus not only will your humble servant ever be thankful, but also the whole country, both officers and people, will be everlastingly obliged by your high favour.

"An urgent petition.

"In Taou-kwang's reign, the 30th year, the first day of the ninth month." (Corresponding to October 5th, 1850.) [It is interesting to observe the adoption of the Chinese mode of dates. Taou-kwang, literally "Reason's Glory," is the name of the Chinese Emperor, who died in 1850.]

"The dutiful petition of Ma Leang-tsae, (and others), of Lewchew, setting forth the real truth.

"We learn from rumour that certain persons of your honourable ship being sick, and requiring Bettelheim's medical aid, have slept in the quan-kwo-she temple (Dr. B.'s residence.) Now if this should lead to their permanently remaining here it would cause us much uneasiness. Our humble country is poor, and the few sorts of grain which we grow are scanty. During the period of Bettelheim's residence here, all of us, from the highest down to the lowest classes, have been constantly occupied in business concerning him, so as to be unable to attend to our avocations, which exposes us to severe want. If still more persons remain here, our troubles will be greatly increased, so that the nation will assuredly be unable to subsist.

"Our country is destitute of commerce; we are but a little nation; and the islands belonging to us are very small. Possessing neither gold, silver, copper, nor pearls--no raw, nor wrought silks, and having only a few kinds of grain and vegetables, we scarcely deserve the name of a kingdom.

"Ever since the time when the Ping-han (the title of the former government of Lewchew), was raised to the rank of an hereditary kingdom under the Ming (the last native Chinese) dynasty, and became tributary to China, whenever we carry tribute thither, we buy thence silk official caps and dresses, with medicines and other articles.

Our supplies from China are, however, insufficient to meet our wants. But as the Tuchara islands (probably Latzuma) belonging to Japan, trade with all neighbouring countries, we procure thence not only articles necessary for the tribute and various Chinese goods for carrying on our inland trade, but also rice, grains, timber, iron, copper, tea, and other articles, in small and insufficient quantities. Grain being scarce in our poor country, our daily food consists merely of sweet potatoes, of which we have not one pound too many.

When visited by the calamity of a typhoon or drought, even though we derive a moderate subsistence from the wild sago tree, we should be unable to appease our hunger, and we should be compelled to borrow rice from those islands, which we consider as our special security against starvation. Alas such is the melancholy statement respecting our country.

"When, therefore, in the 16th year of Kea-king (1812?), and in the 17th and 18th years of Taou-kwang (1837, 1838), ships came from England, America, and France, for the purpose of trading with us, we declined on the grounds before mentioned. In the 11th year of Taoukwang (1831), an English merchant-vessel arrived, wishing to trade. We again refused on the same grounds. In the 11th month of last year (December, 1849), an envoy from the English government arrived to deliver a despatch on the subject of commerce, but we again declined as before.

"Now, according to the above statement, it will be seen, that being but a poor people, and destitute of wealth, we cannot carry on an extensive trade with other countries. Tuchara is not better circumstanced than our own island. Our coarse sugar, grass-cloth, &c., are bartered for the rice and other grain of that island, and for other articles, both for the due payment of our tribute and for home consumption. Such a petty trade, therefore, is very different from the extensive commercial methods of other countries for gaining wealth and obtaining riches.

"We hear that the laws of Japan severely prohibit promiscuous trading with other countries. It is only at the port of Chang-ki (Nagasaki?) where officers are stationed to keep a strict watch, that a fixed and limited number of ships with merchandise are admitted; which port Chinese and Dutch merchants visit annually for trade.

"The people of Tuchara, although belonging to Japanese territory, yet being situated nearer to us, are permitted to trade with this place. But on their returning home, if they were to import prohibited articles, by smuggling, in the event of detection by the public officers they would be severely punished.

"If we were to trade with you, it will follow that the people of Tuchara will, in accordance with Japanese laws, be strictly prohibited from any intercourse with us. Even in the present year we are not only deficient in articles required for the tribute, but also exposed to severe want in respect to articles for home consumption. If this should happen to be a year of famine, we have no means of remedying such an emergency, and must perish with hunger.

"Further, we have no medium of currency. On account of the scarcity of articles sold in the market, foreign ships on their arrival are unable to purchase a supply of provisions, and we therefore appoint special official purveyors to procure, if possible, the needful supplies from the villages.

"Further, during the course of several years past, both yours (English) and American ships have from time to time arrived, requiring large supplies, which gives employment to many of the officers and people, who are thus deprived of leisure for attending to their own avocations. This is a source of great inconvenience.

"Now as to the religion of the Lord of Heaven (the popular term by which Christianity, or rather the Roman Catholic form of Christianity, has been known), we have from ancient times attended to the doctrines of Confucius, and found therein principles wherewith to cultivate personal morality, and to regulate our families, each according to our circumstances and condition in life. We endeavour also to carry out the government of the country according to the rules and maxims which have been handed down to us by the sages, and are calculated to secure lasting peace and tranquillity.

"Besides, our gentry, as well as the common people, are without natural capacity; and, although they have attended exclusively to Confucianism, they have as yet been unable to arrive at perfection in it. If they should now also have to study, in addition, the religion of the Lord of Heaven, such an attempt would surpass our ability, and the heart does not incline to it. The people of Tuchara also are attached to the Confucian religion and classics, and bestow great study upon them. Should they hear that we are studying a new religion, viz., that of the Lord of Heaven, they would most certainly desist from all intercourse with us.

"This our regular and clear petition, with knocking of heads, we submit to the penetrating investigation of your excellency. Look down in pity upon us; cease to send people to remain here; and desist from the attempt to trade with us and to teach us Christianity. Thus the whole country, government officers and people, will be thankful for ever.

"An urgent petition.

"Taou-kwang, the 30th year, the 1st day of the 9th month."

In the evening of the same day, I took a walk among the tombs on a promontory overlooking the sea. Not even in China had I ever seen so vast a number of tombs constructed of so expensive and durable a form. They formed a mazy labyrinth of well-constructed masonry; and, like a number of streets intersecting each other in an irregular direction, these houses of the dead, in neatness, solidity, and extent, rivalled the abodes of the living. A wall on either side, from twelve to twenty feet in length and eight in height, formed the little outer court.

Opposite to the entrance was a little door leading into the vault dug out of the rising ground, and extending several feet within, the portion behind sloping upwards, and being rounded off, so that the whole enclosure presented the form of an omega (W). The large sums which must have been expended on these tombs would appear inconsistent with the universal prevalence of deep poverty among the inhabitants. These family mausoleums are the resort of the people in the evening.

They are said to spend much of their time at the tombs, and make periodical offerings to the spirits of their departed ancestors. As in China, so in Lewchew, they present offerings of eatables, and, when the materials of a feast have remained a certain time that the ghost may consume the subtle ethereal portions of the meat, the grosser material particles are taken away, and are feasted upon by the living at their own homes.

There is also the same weeping at the tombs. At the new and full moon, however, there are apparently no festivals. At each of the four seasons, and especially at the period of the new year, there is a general holiday. At the latter a whole month is given to feasting and idleness. The people do not seem to have imported from China the feast of lanterns. They have, however, the same custom as in China, of setting apart altars for burning slips of paper inscribed with Chinese characters, and for preventing any dishonour to literature by suffering written paper to be thrown carelessly away and trodden irreverently under foot.

The principal superstition which meets the eye in passing through the streets is the great number of little images placed on a little opening or chimney in the tilted roofs of their houses, which are intended as charms and preservatives from conflagration. Sometimes they make a model of a house, and solemnly consume it by fire, in order to appease the divinity supposed to preside over that element, and to avert such a domestic calamity.

On Sunday, October 6th, I went in a kagoo, a simple conveyance to which I shall afterwards allude, to a populous suburb named Tumae, and situated on the shore of the northern harbour, in order to proceed to the Reynard, and hold divine service on board. On our return to the landing-place at Tumae, at about two, p.m., we found nearly a hundred people awaiting our arrival, chiefly belonging to the literary class.

Dr. Bettelheim addressed them for a few minutes, and, as my interpreter, made some communications from myself. He was proceeding in his address with great action and energy of manner, when one of the leading men slightly moved from his position, and the whole company, as if an electric shock had been sent through the whole line, suddenly dispersed on all sides. One principal byestander, a fine old man of sixty, had invited us to a neighbouring temple, to which we directed our steps. In this building Captain Basil Hall and his party had been quartered during their stay; and here also the French missionaries, who attempted a location in Lewchew, had resided.

We were for some time seated unconsciously on the little bench which served as a Romish altar, and a stage for the image of the Virgin Mary. There was no other seat in the room, and the Lewchewans were squatted on the ground around us--chairs or stools being a degree of civilization to which this people have not yet attained, except in the houses of their rulers.

Dr. Bettelheim here interpreted for me an address to the people, about sixty in number, around us, adapted to the circumstances of our arrival amongst them, and a plea for their patient and unprejudiced listening to the instructions of the missionary. Among the persons present I observed the countenances of some of the spies whom we met standing around the magistrates on the preceding day.

In about ten minutes there was again the secret signal and gradual dispersion. The old man, our host, who apparently wished to show attention, and disarm displeasure, and, at the same time, to prevent intercourse with the people, now discovered his real object, and appeared greatly afraid of having over-acted his secret instructions. He openly proposed our leaving the premises; his tenor increased every moment; and as we lingered to take a leisurely survey of the pretty garden and shrubbery which enclosed the building, his anxiety seemed to increase to an extent almost endangering his civility.

The kagoo in which I was borne, is a vehicle only one remove above the contrivances of savage life. It is a mere box, similar in size and shape to that in which meat is hung on the poop of a ship. This little machine, being about two feet and a half in height, and slightly roofed at the top, is open at the sides, with the exception of a little loose used at option, and is borne on the shoulders of two men, one before and the other behind, who run along with the weight suspended diagonally forward, at an uneasy, irregular pace of five miles an hour, resembling a jog-trot.

The traveller enters at the side, and has to squat or sit in Turkish fashion on the bottom of the vehicle, occasionally grasping the pole above to prevent being shaken out into the road, and generally clasping his knees with his hands close to his chin. A more primitive invention it is impossible to conceive. This is the only carriage known in Lewchew; and the only improvement in those used by the highest rulers consists in a little additional width to the floor.

Seated on this machine, I was carried, or rather swung, along the streets of Tumae, over a little arm of the sea, and finally reached my temporary abode in Napa. It was with difficulty I procured this vehicle. No hired conveyance was to be had; but as the distance to be traversed was five miles in all, and no other means of procuring one were open to me, a request was addressed to the authorities; and after a little delay and apparent reluctance, a kagoo was placed at my disposal by the government.

I had a relay of four bearers, whom I wished liberally to repay for their toil; but no inducement could prevail on them to receive any money. They shrunk back at the sight of a dollar, as if it had been certain destruction to them. No expostulation could prevail upon them to receive the money.

They said that they were mere public slaves, and that it was not lawful for them to receive money for their labour. On its being held out to them again, they bowed, almost with their heads to the ground, and every one in succession refused, probably distrusting one another, and fearing an accusation to the authorities, although they showed no unwillingness to drink off each a glass of sackee, a spirituous beverage made on the island.

Soon after our return from the ship, the wind, which was very violent, quickly increased to a strong gale, which, during the night, threatened to bring down the part of the temple in which I was quartered upon our heads, and effectually prevented the possibility of rest.

At ten p.m., five special messengers came to us from the governor of Napa, to express his sympathy with us in the danger of our ship in the harbour, and his regret at not having earlier sent an offer of additional ropes and cables for our captain, in order to render the ship more secure in outriding the storm.

The next morning these little friendly advances were somewhat in danger of interruption, through various renewed attempts on the part of the ta-foo, or petty constables, to bring us a note from the tsung-li, through his subordinate the governor of Napa, and thus to avoid the appearance of equality in holding direct intercourse with us.

The note was declined; afterwards a letter, probably concocted at the entrance in the police shed, was soon brought in, purporting to be from the tsung-li himself. An intimation was conveyed to the authorities that the captain would hold no communications except with the responsible head of their government.

The next day passed away in the dilatory arrangements preparatory to our interview with the tsung-li. It was evident to them that the Reynard was likely to remain some little time at Lewchew; and the native authorities seemed to have speedily arrived at the wise conclusion that a meeting between the highest official and the captain would be in the end most conducive to their own interests, and expedite her departure.

On Wednesday morning, October 9th, the tsung-li came down from the capital, and special messengers soon came to conduct us to the place appointed for the interview, about a quarter of a mile from our temple. Captain Cracroft was attended by his officers, in full uniform, and about fifty sailors and marines, who, at the sound of drum and fife, marched in regular order to the public hall, in which the officials awaited us.

We passed through an outer court, and at length reached a small inner square, where the sailors and marines were drawn up opposite to a kind of body-guard of Lewchewan attendants; the scene being a mixture of form, physiognomy, and dress, which partook somewhat of the grotesque.

The tsung-li, with the second official in rank, the pooching, received us in a room on a little raised platform, with open sides, where tables were laid out in preparation for an entertainment. Several subordinate officers stood around, our old acquaintance Chang among the rest, who again, on this occasion, fully vindicated his claim to be considered an adept in oriental diplomacy.

Almost before the usual salutations had been exchanged, Chang made sundry advances to my Chinese secretary, Chung-chun, whom he wished to entertain privately in a separate room, but who nevertheless strictly obeyed my injunctions to remain at my side.

Chang also seemed very anxious that all communications from the latter should be made in a low tone of voice, which he on his part repeated in a whisper to the tsung-li. But my occasionally speaking a Chinese sentence in an audible tone direct to the two high officials, and my requesting Chung-chun also to adopt the same course of proceeding, prevented Chang from entirely distorting, and misinterpreting our meaning among a crowd of Lewchewans, many of whom had a slight knowledge of Chinese. A great number and variety of dishes and liquors necessarily appeared and were removed, and preparation was made for the principal matter of business.

The tsung-li repeated the request that the captain would take away Dr. Bettelheim by force in his ship. He stated that a year ago a petition had been sent to the British government to the same effect, and expressed his disappointment at our not having brought, as he had expected, a favourable reply. He spoke also of a communication to the British through Seu, the Chinese imperial commissioner. He was informed that the arrival of the Reynard, and the instructions delivered by the captain, were in themselves a sufficiently plain reply in the negative.

The tsung-li and the poo-ching, together with the governor of Napa, now fell on their knees, and knocked their heads on the floor, beseeching the honourable envoy to have pity on their poor country, and to avert the danger of famine by foreigners coming to live among them. Afterwards they presented a written petition to him to the same effect; and when they found it ineffectual, they delivered into his hands a large document in an envelope, a foot and a half long, purporting to be a petition to the Queen of Great Britain.

They also handed in a written exculpation of themselves in the matter of the nine articles of complaint laid against them by Dr. Bettelheim. These were perused in their presence, and it was intimated that they should be forwarded to the British governor of Hong Kong.

They were again reminded that Dr. Bettelheim was willing to pay for every article; that he came with a benevolent object and disinterested motives; and that while the British government would punish any of its subjects who transgressed the law of a friendly power, it would view with displeasure any bodily violence inflicted on a British subject peaceably residing among them.

They were shown the edict of toleration in favour of the Christian religion issued five years previously by the Chinese emperor Taou-kwang. Gradually they became more reconciled to Captain Cracroft's determination; civilities multiplied; presents of tobacco, grass-cloth, cane-pipes, pouches, purses, &c., were offered to each of us, and accepted; and an intimation was conveyed to them indulgence would be extended to all past occurrences, in the hope that they would treat Dr. Bettelheim well for the future.

The conversation was led towards the circumstance of the gate of the citadel at Shui-di having been, on the previous day, shut against a party of the Reynard's officers, during a ramble on shore; and surprise was expressed that they had behaved so rudely towards friendly visitors, with the request also that they might be allowed to have ingress within the citadel on their next excursion.

This request seemed to raise a temporary cloud over the horizon, and the tsung-li, the poo-ching, and Chang, were in great consultation, anxiously debating a means of escape, until I made the communication that we regretted to perceive that it was an unpleasant topic, and that as friends we did not wish to cause them any disagreeableness, and did not any longer press the request. This was a peace-offering to Chang, who thereupon lavished many attentions and commendations upon myself, frequently reverting to the subject, and repeating our goodness and generosity.

He tried one more effort privately to induce me to prevail upon the British envoy to take away Bettelheim by force; and when that was represented as hopeless, he urged me very much to use my entreaties with the English emperor to send a ship shortly, and remove Dr. Bettelheim. The highest officials now received and accepted an invitation to pay us a visit on board the Reynard, that we might have an opportunity of returning their hospitality and presents previous to our departure.

We returned in the same order to the temple through crowds of wondering Lewchewans, with some hope that the main object of the Reynard's visit would be substantially gained, and that the native rulers would have an opportunity of appreciating British hospitality as fully as they had tested British firmness. At our departure from the public court-house even Chang seemed, for a season, to lose his plotting anxious looks, and to assume an air of friendly satisfaction.

Late in the day the authorities, at our request, sent two kagoos, with relays of bearers, to carry myself and a companion to the capital. We had arranged for Dr. Bettelheim to meet us at a certain point of the road and to accompany us. From our ignorance of the language we were unable to prevent our bearers from hurrying to the landing-place at Tumae, whence they probably expected we were about to proceed to the Reynard.

On our meeting Dr. Bettelheim, he directed our bearers to retrace their steps to the turning in the road which, between Napa and Tumae, branches off to Shui-di. At this juncture a spy presented himself, and finding his entreaties for us to return ineffectual, he, by some secret intimidation, prevented our bearers from proceeding. We, however, on our part, were determined not to be disappointed in our intended trip.

The spy then expostulated with us on the distance, the lateness of the hour, and the approach of sunset. Finding that we still persisted, he addressed a few words to our bearers, and then preceded us, clearing the roads and lanes of every Lewchewan by a wave of his fan.

Our bearers now went forward at a slow pace, and with evident reluctance, till we arrived at the point of road which branched off to the capital. Here the spy took his station, and our men laid us down, until our fixed resolution, and their fear of being involved in some unpleasantness from thus acting against our wishes, decided the matter.

They resumed their load, and proceeded at a slow pace, so that our remaining distance of four miles to Shui-di was not accomplished till after dark. The road was of varying width, in no place being less than twenty, and in some parts being fully seventy feet wide, with a well paved causeway of coral, which had the appearance of a macadamized road.

We passed, soon after leaving Tumae, a large Budhist monastery, containing several monks, and situated as usual in the most picturesque vicinity. Groves of pine and fir, intermingled with bamboo, were dotted over the country; and the rural homesteads, surrounded by fields in a high state of cultivation, afforded a pleasing landscape to the view. The sweet potato seemed to be the all-prevailing vegetable, forming, like the potato in Ireland, the principal means of subsistence to the people.

There were fewer external signs of great poverty than are commonly to be seen in villages in the south of China; and if, to have few wants, and those easily satisfied, constitute riches, the Lewchewans may be considered a contented, cheerful people. While viewing their merry countenances, and listening to their light-hearted voices, I could not help reflecting on the universal law of compensation by which a wise and merciful Providence equalizes the conditions of mankind--causing the sons of luxury to pay the price of civilization in many sorrows and cares, from which these children of nature enjoyed an immunity and exemption.

The sweets of civil liberty, of social refinement, or of personal ambition, possess no charm for the man whose chief happiness is to satisfy hunger and to repel want. Regarding men as the mere subjects of an animal existence, we might perhaps subscribe to the opinion that the Lewchewans, with their few wants and petty cares, are as happy as the peasantry of a Christian land. But such will not be the views of him who looks on man as originally created in the image of God, and destined to outlive and outgrow the petty interests of time, and to dwell for ever in the glorious presence of the great Eternal.

We passed over some rising ground, through which the road conducted us, with a well wooded country on either side, until we entered the outskirts of Shui-di. A number of neat dwellings, apparently tenanted by a more wealthy class of natives, lined the broad street through which we were borne, and which, at the distance of half a mile, brought us to the citadel. Much interest and curiosity was excited by our arrival; there were no signs of fear, nor any apparent desire to enter into conversation. Broad and lofty arches at intervals crossed the street, dividing the little city into wards.

Long lines of faces, gleaming from the reflected torchlights, appeared above the court-walls on each side, gazing at us as we passed along. Fire-flies illuminated the air in all directions, and made the sky glitter with sparks of light. Under our feet glow-worms lay so thick that scarcely a square yard of ground was unoccupied by these glittering insects.

Beautiful shrubs and gardens adorned the streets on each side, and made upon us a favourable impression respecting the condition of the inhabitants, which, it is to be feared, would not be confirmed by an actual inspection of the interior.

The citadel is surrounded by a high and well constructed wall of great strength, and is approached by a massive gate, under which we now took up our station in a guard-house, forming a long shed, roofed over on the top, and open in front and at the sides, with a few wooden pillars. In this several people, apparently watchmen or soldiers, were sitting, and paid us many attentions, bringing some tea, and offering us tobacco.

In a few minutes there was a large concourse of people, who, favoured by darkness, and exposed to less risk of detection and punishment, eagerly came together, and remained willing listeners to the address which followed. Dr. Bettelheim requested me to speak some words to the surrounding crowd, which he might interpret to the people.

The circumstance of a missionary having fixed his location among them--the incalculable benefits which the reception of his message would confer on them--the love of the Son of God in coming into this world of evil and misery to die for sinners, and reconcile them to the lost favour of heaven--their duty and responsibility under such circumstances to give heed to the Gospel message, and to welcome the messenger who came with these good tidings of great joy,--such were the principal topics on which we enlarged.

The missionary, with much energy of bodily action, and with much persuasiveness of tone, seemed to expostulate, to entreat, and to invite. Four hundred countenances, lighted up by the flickering glare of torches, hung upon his words with breathless and attentive silence. It was a scene which I shall not easily forget. It formed a missionary incident unhappily rare amid the occurrences of this interesting and memorable week.

The place--the occasion--the assemblage--the time--all served to deepen the feeling of solemnity, and interest, and awe, never to be effaced till the archangel's trump on the last great day shall summon every individual of that motley throng to stand before the common bar of Divine judgment.

About ten minutes had elapsed, when a slight motion in one part of the crowd, was transmitted instantaneously through the whole mass. The agents of the Lewchewan government, well known to the people, probably made their appearance, and gave the secret word or sign. In a body they all retired fifty yards, where, screened by the darkness and distance from our lights, they stood for a time unwilling to depart. An earnest conversation now took place between ourselves and some Lewchewans, whom, from their fearless intercourse with us, we judged to be officers connected with the government.

Every attention was shown us, and our wishes were met in every respect. There was now no difficulty in procuring bearers or conveyances, when we spoke of our return to Napa. Each man vied with his neighbour to show respect to the foreign visitors. Dr. Bettelheim, who had hitherto walked, was speedily provided with a kagoo, and we set out on our return.

Three vehicles, with relays of bearers, and torchbearers, formed a party of nearly twenty conductors. Some pretty-featured, fine-spirited boys, belonging, with the rest, to the caste of public slaves, ran along chattering and laughing, bearing immense blazing torches, formed of a bundle of rattans, at the rate of six or seven miles an hour.

There was now no need of a stimulus, nor any complaint of fatigue. We were swung along to the tune of some native song. The Lewchewan peasants turned out at every little hamlet to see us pass. We soon arrived at the cross-road, branching off to Tumae and Napa, where our friend, the spy, who, three hours before had in vain tried to hinder us from proceeding, looked disappointed and melancholy, and seemed to confess that he was defeated. We were, however, good friends at parting, and exchanged distant salutations.

A quarter of an hour afterwards, we arrived at our temple residence, where I wished to remunerate our good-natured, lively hearted bearers, but it seemed to be in vain. Though protected by darkness from danger of observation, they stoutly declined. One poor slave alone, grasped the dollar secretly placed in his hand, over whose fears the love of money had for the present achieved a conquest.

When viewed through the dull medium of prosaic reality, how much of the romantic interest attaching to these poor islanders, in reference to pecuniary transactions, vanishes away. The touching instances of Lewchewan hospitality, and their unwillingness to receive any money in return for their presents, as related by former visitors, will probably receive a somewhat different explanation in the minds of those who may peruse these pages.

It will be convenient to subjoin in this place, a brief general description of Lewchew, as abridged from a MS. drawn up a few months previously by Dr. Bettelheim. The descriptions of a former traveller of the character and habits of the Lewchewans, are animadverted upon by him in terms, much of which I forbear to quote:

"I should be happy (he writes) to bear witness to the value of this production. But I cannot. I feel bound to say, that the whole vocabulary, together with all things relative to the character of the Lewchewans, are quite without use. The Lyra lay here about six weeks. We have been here three or four years. This makes all the difference."

The great Lewchew is land extends about sixty miles in length from N.E. to S.W., being about fifteen in average breadth. It is calculated to contain about 50,000 inhabitants, about 20,000 of whom belong to Napa, a somewhat less number to Shui-di, the capital, and the rest are scattered over the rural portions of the country. The whole land seems divided into an eastern and western slope by a mountainous ridge through the whole length of the island.

A tolerably good inland road, now approaching the eastern, now the western coast, runs over this ridge, its table lands, and intersecting valleys. There are besides two coast-ways, very wretched ones, leading from the extreme south to the extreme north." There is but one river, about forty feet wide in the northern part of the island, with a number of small mountain streams, serving for the purpose of irrigation.

It is strange that our imperfect acquaintance with oriental empires should still throw some degree of uncertainty on the real relations subsisting between Lewchew, Japan, and China respectively. On the whole, however, it seems far the most probable opinion, that Lewchew was peopled by a colony from Japan, to which people their physiognomy, language, and customs, bear a close affinity; and that to China they owe the far more important debt of their partial civilization and literature.

The government of the country appears to consist in a grievous oligarchy of literati, immediately dependent upon Japan. They stand in great fear of the latter country, and look to it, and not to China, for protection in time of need. They have an historical tradition that a few hundred years ago, during the Ming dynasty, a war broke out between China and Japan, during which, the former wanting to detach Lewchew from the latter, raised it to the dignity of a separate kingdom. In token of vassalage, every new king receives a formal investiture from a Chinese officer, specially deputed and sent for that purpose from Foochow; to which city, also, a biennial tribute-junk is sent from Lewchew.

At the Tartar invasion of China, and the commencement of the present foreign dynasty, above 200 years ago, about thirty-six Chinese families, unwilling to conform to the Tartar changes of costume and rule, emigrated to Lewchew, the descendants of whom have become generally the schoolmasters of the country, and amalgamated with the people.

In illustration of these views, I proceed to quote largely from the MS. in my possession--Dr. Bettelheim writes--

"For my part, I am perfectly persuaded this country, though independent to a certain extent (its ruler being permitted, for a good contribution to Peking, to assume the high-sounding title of king), yet is to all ends and purposes an integral part of Japan. I have sundry good grounds for believing this.

"And, first of all, there is a Japanese garrison quartered in Napa." [Dr. B. states the circumstances which led to his discovery of Japanese soldiers engaged in cleaning and polishing their fire-arms; and dwells on this fad as an instance of the wrong impressions which formerly existed in the minds of Europeans as to the total absence of military armour and accoutrements among the Lewchewan people.]